Abstract

Introduction:

We examined the association between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) use and risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among prostate cancer patients.

Methods:

We included 241 cognitively unimpaired men, aged 70-90, with a history of prostate cancer prior to enrollment in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Using the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records-linkage system, ADT use and length of exposure were abstracted. Follow-up visits occurred every 15 months and MCI diagnoses were made based on clinical consensus. Cox proportional hazards models, with age as the time scale, were used to examine the association between ADT use (yes/no) and length of exposure with the risk of MCI adjusting for education, APOE, depression, and the Charlson Index score.

Results:

There was no association between any ADT use (27.8% of participants) and risk of MCI in the multivariable model [hazard ratio (HR), 1.25; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.75-2.10]. Although not significant, there was an ADT dose-response relationship for risk of MCI: <5 years vs. no use (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.60-1.96) and ≥5 years versus not use (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.83-4.27).

Conclusions:

Androgen deprivation therapy use among prostate cancer patients was not associated with an increased risk of developing MCI.

Keywords: prostate cancer, cognition, longitudinal study

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 11% of men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer within their lifetime. Over 3 million men are currently living with the disease in the US alone.1 While there are many options to treat prostate cancer, more than half of prostate cancer patients will receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) at some point during their treatment.2 ADT works by lowering the levels of testosterone, a hormone that fuels the growth of prostate cancer cells. Given in conjunction with radiation therapy, ADT has been shown to have a survival benefit in subsets of patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer.3,4

Although ADT has been associated with a number of side effects including fatigue, erectile dysfunction, hot flashes, and osteoporosis5,6 there is conflicting evidence7-10 as to whether ADT may be associated with an increased risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. One study using animal models reported that the reduction of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels, a metabolite of testosterone, resulted in an increase in amyloid-beta, a hallmark pathology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).11 Supplementation with DHT prevented this increase. Other studies have also suggested that both testosterone and luteinizing hormone can modulate amyloid-beta accumulation.12 Thus, it is possible that ADT is associated with an increased risk of AD.

The complex nature of cancer’s disease course has been found to impact cognition as well. Multiple factors such as DNA damage, psychological factors like depression, as well as some of the medications or procedures given as treatment may contribute to the cognitive decline seen in some cancer patients. This cognitive decline limits their capacity to make informed decisions and negatively impacts their quality of life.13

Few studies have longitudinally examined the association between ADT use and risk of cognitive impairment. A recent retrospective study14 utilizing the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare linked database (SEER) of over 150,000 prostate cancer patients diagnosed from 1996 to 2003, reported an association between ADT use and subsequent diagnosis of dementia, over a mean follow up of 8.3 years. Although this was the largest study to date examining ADT use and risk of dementia, limitations included the use of diagnostic codes for a diagnosis of dementia and the assessment of ADT use only within 2 years of prostate cancer diagnosis. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine whether the use of and length of exposure to ADT among prostate cancer patients was associated with an increased risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), determined using a clinical consensus conference, in a population-based longitudinal study of cognition and aging.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Study on Aging (MCSA) is a prospective population-based study that began in 2004 in Olmsted County, Minnesota. The study initially recruited Olmsted County residents between the ages of 70 and 89 using an age- and sex-stratified random sampling design after enumerating the County population using the Rochester Epidemiology Project.15 The present analyses focused on all men aged 70 and older at their initial MCSA baseline visit who had a history of prostate cancer.

MCSA visits occurred every 15 months and included a physician examination, an interview by a study coordinator, and neuropsychological testing administered by a psychometrist.16 Physician examinations included a review of the participant’s medical history, a neurological examination, and administration of the Short Test of Mental Status.16 Study coordinator interviews included participant demographic information and medical history and the participant and informant Clinical Dementia Rating scale.17 The neuropsychological battery included nine tests covering four domains (memory, language, executive function, and visuospatial).

For each participant, performance in a cognitive domain was compared with the age-adjusted scores of cognitively unimpaired (CU) individuals previously obtained using Mayo’s Older American Normative Studies.18 This approach relies on prior normative work and extensive experience with the measurement of cognitive abilities in an independent sample of subjects from the same population. Subjects with scores around 1.0 SD below the age-specific mean in the general population were considered for possible cognitive impairment. A final decision was made after considering education, occupation, visual or hearing deficits, and reviewing all other participant information. The diagnosis of MCI was made by a consensus agreement between the study coordinator, examining physician, and neuropsychologist using published criteria.19 The diagnosis of dementia and AD20 were based on published criteria. Participants who performed in the normal range and did not meet criteria for MCI or dementia were deemed CU.

Prostate cancer diagnosis and use of ADT and other therapies were abstracted using the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records linkage system. The variables abstracted from the medical records included: date of diagnosis of prostate cancer (including recurrent), staging, and treatment type (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal treatment, other). Androgen deprivation therapy methods were also identified (GnRH agonists, antiandrogens, orchiectomy, other) and length of exposure to these drugs were recorded along with time from ADT exposure to enrollment into MCSA.

Demographic variables (eg, age and education) were collected by self-report during the in-clinic exam. Medical comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson comorbidity index.21 Depression was defined as a score of 13 or greater on the Beck Depression Inventory.22 Participants’ blood samples were used to determine APOE genotype.

We summarized the characteristics of the participants by whether or not ADT was used prior to their MCSA baseline visit. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the association between ADT use, and length of use, with risk of MCI. Follow-up time was computed from the time of entry into the MCSA (baseline) to the midpoint between the last assessment as CU and the date of incident MCI (or dementia). Persons lost to follow-up were censored at their last follow-up. Competing risk models were further utilized to account for those who died before incident MCI. Age was used as the time scale for these models. Multivariable models adjusted for education, APOE genotype, depression, and the Charlson comorbidity index.21 All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and a standard alpha value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Of the 315 MCSA participants with a history of prostate cancer at baseline enrollment, 253 (80.3%) were determined to be CU. Of these 253, 12 did not have follow-up data and were thus excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 241 participants for the current study. These participants were a median age of 78 years, and had a median education of 14 years (Table 1). Of the 241 men with a history of prostate cancer, 67 (27.8%) received ADT as treatment (Table 1). Compared to participants who did not use ADT, those who did had a higher number of median comorbidities via the Charlson Index (8 vs. 4, P<0.001), but did not differ with regards to age, education, APOE genotype, or depression. The participants had a mean of 3.8 follow-up visits, equating to 4.8 years, during which 73 (30.3%) developed MCI.

TABLE 1.

Participant Characteristics by ADT Use Prior to MCSA Baseline

| Characteristic | No ADT Use (n=174) |

ADT Use<5 years (n=47) |

ADT Use ≥ 5 years (n=20) |

Total (n=241) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline | 78 (70, 90) | 78 (72, 87) | 82 (71, 90) | 78 (70, 90) | 0.12 |

| Education, years | 14 (6, 20) | 14 (6, 20) | 14.5 (6, 20) | 14 (6, 20 | 0.69 |

| Presence of an APOE4 allele | 47 (27.0%) | 12 (25.5%) | 4 (21.1%) | 63 (26.3%) | 0.85 |

| Depression | 13 (7.6%) | 6 (13.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 22 (9.3%) | 0.35 |

| Charlson index | 4 (2, 15) | 7 (2, 17) | 10 (3, 16) | 5 (2, 17) | <0.001 |

| Age at diagnosis | 69 (51, 87) | 73 (61, 84) | 67.5 (54, 79) | 70 (51, 87) | <0.001 |

| Metastatic disease | 10 (5.7%) | 12 (25.5%) | 7 (35.0%) | 29 (12.0%) | <0.001 |

| Incident MCI | 50 (28.7%) | 15 (31.9%) | 8 (40.0%) | 73 (30.3%) | 0.56 |

| Follow-up time | 4.7 (0.0, 13.5) | 3.4 (0.1, 13.2) | 2.5 (0.6, 8.5) | 4.3 (0.0, 13.5) | 0.19 |

N (%) for categorical data and median (range) for continuous or count data are presented.

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; APOE4, apolipoprotein E ε4; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

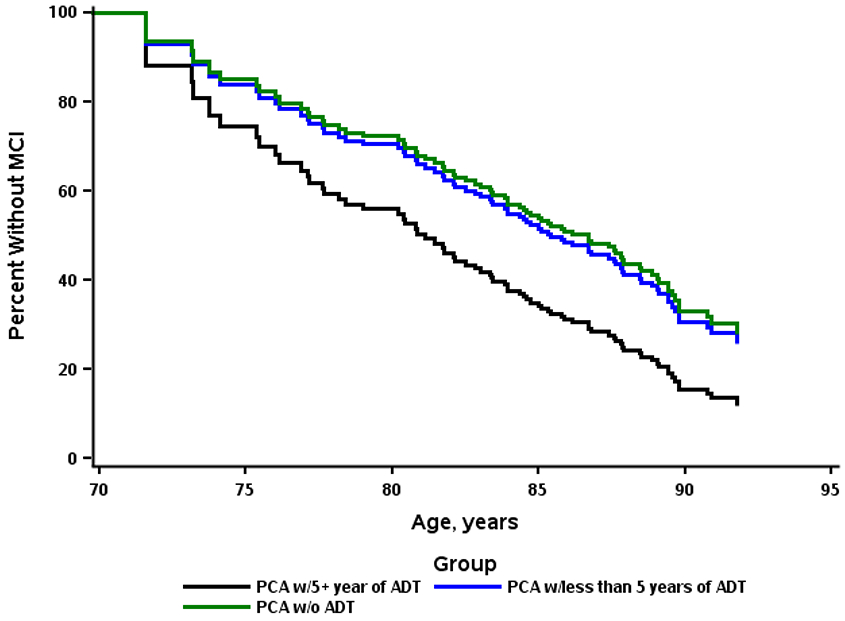

There was no association between ever using ADT for prostate cancer treatment and risk of MCI in either univariable (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.85-2.32) or multivariable (HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 0.75-2.10) models (Table 2). Exploratory analyses examining the functional form of the duration of ADT exposure using splines suggested a leveling off of effects at approximately 5 years. Therefore, in additional analyses, we examined whether there was a dose-response effect of ADT use on the risk of MCI. Compared to no ADT use, there was no association between <5 years of ADT use and risk of MCI (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.60-1.96), but there was a trend for those with 5 or more years of use to be associated with risk of MCI in multivariable models (HR, 1.89; 95% CI, 0.83-4.27; Table 2 and Figure 1). Using competing risk models the risk of MCI was attenuated for those with <5 years of ADT use (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.45-1.73) and 5 or more years of use (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 0.61-3.88) compared to those with no use (Table 3). Additional analyses were conducted to examine time dependent exposure variables such as metastasis, cumulative ADT dose through MCSA follow-up, and prostate cancer treatment modality. However, none of the time-dependent analyses were significant and, thus, are not reported.

TABLE 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis for ADT Use at 5-Year Cutoff

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADT exposure | N | Events | HR (95% CI) | P-value | N | Events | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

| No history of ADT use | 174 | 50 | ref | 170 | 48 | ref | ||

| History of any ADT use | 67 | 23 | 1.41 (0.85, 2.32) | 0.183 | 65 | 23 | 1.25 (0.75, 2.10) | 0.398 |

| No ADT use at baseline | 174 | 50 | ref | 170 | 48 | ref | ||

| <1 year ADT use at baseline | 31 | 10 | 1.15 (0.58, 2.27) | 0.698 | 31 | 10 | 0.99 (0.49, 2.00) | 0.978 |

| ≥1 year ADT use at baseline | 36 | 13 | 1.71 (0.92, 3.17) | 0.090 | 34 | 13 | 1.61 (0.87, 3.24) | 0.179 |

| No ADT use at baseline | 174 | 50 | ref | 170 | 48 | ref | ||

| <5 year ADT use at baseline | 47 | 15 | 1.21 (0.68, 2.17) | 0.520 | 46 | 15 | 1.08 (0.60, 1.96) | 0.794 |

| ≥5 year ADT use at baseline | 20 | 8 | 2.02 (0.95, 4.30) | 0.069 | 19 | 8 | 1.89 (0.83, 4.27) | 0.128 |

| No history of ADT use | 169 | 50 | ref | 165 | 48 | ref | ||

| Time-dependent ADT use | 72 | 23 | 1.35 (0.82, 2.22) | 0.244 | 70 | 23 | 1.22 (0.73, 2.05) | 0.447 |

Multivariable models adjust for education, APOE genotype, depression, and the Charlson comorbidity index. Age was used as the time scale.

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted survival comparing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) at 5-year cutoff for risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

TABLE 3.

Competing Risks Multivariable Model for ADT Use at 5-year Cutoff*

| Characteristic | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Education, years | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97) | 0.009 |

| Presence of an APOE4 allele | 1.90 (1.12, 3.23) | 0.018 |

| Depression | 1.87 (0.86, 4.08) | 0.114 |

| Charlson Index | 0.97 (0.90, 1.04) | 0.341 |

| <5 years ADT use vs. none | 0.90 (0.47, 1.73) | 0.748 |

| ≥5 years ADT use vs. none | 1.54 (0.61, 3.88) | 0.364 |

Age was used as the timescale.

ADT indicates androgen deprivation therapy; APOE4, apolipoprotein E ε4

DISCUSSION

In a population-based study of initially CU participants with a history of prostate cancer, ADT use was not associated with risk of MCI. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend to suggest a potential association between long-term ADT use (ie, >5 years) and risk of MCI. This finding is congruent with previous studies9,10 that did not find an association between ADT use and cognition. However, this finding does contradict other studies,7,8 including a meta-analysis of 14 studies, which did find associations between ADT use and cognitive impairment. Some of the discrepancies in these findings may be attributed to the varying lengths of follow up, from 6 months up to a median of 4 years (for this study), type of cognitive tests and the MCI diagnostic process and the study of different types of ADT. Indeed, a recent systematic review23 cited a lack of extended follow-up and the heterogeneity of the cognitive evaluation and definition as two potential limitations of past studies.

Strengths of the current study include an extensive neuropsychological battery for the diagnosis of MCI and a prospective follow-up of over a median of 4 years. Limitations of the study also warrant consideration. First, is the presence of survival bias. In order for patients to be included in the study, they must have survived their prostate cancer diagnosis and be enrolled in the MCSA study. Those with a more aggressive disease would be expected to have a shorter survival and thus would not be included in the analysis. Time from prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment to MCSA inclusion proved to be a challenge during analysis as there was no consistent follow-up or monitoring during this time, with multiple years unaccounted for prior to baseline cognitive evaluation. Second, this population may not be generalizable to other populations that are more racially and ethnically diverse than the residents of Olmsted County, MN. However, MCSA patients are representative of the population of the upper Midwest. Third, there are multiple types of ADT (eg, GnRH agonists, anti-androgens) that have different mechanisms of action and could differentially relate to risk of MCI. In the current study, we were not able to examine ADT type due to limited numbers and the fact that, in the modern era, GnRH agonists or antagonists are used for the majority of men. Lastly, this study was a secondary analysis of existing data and the sample size was relatively small.

With conflicting results in the literature,7-10 it is important for physicians to have a conversation with their patients on the potential cognitive side effects of extended ADT use. Although this study found no association between ADT use and risk of MCI, there was a trend towards a potential risk. This, combined with mixed conclusions on previously published data, warrants further exploration of the subject. Future directions may want to explore the effects of ADT use and duration on specific cognitive domains, as previous literature cites a potential deficit in executive and visuospatial functions in patients with low testosterone levels.24

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging grants U01 AG006786, U54 AG44170, and RF1 AG55151, the GHR Foundation, CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 AG034676).

R.C.P. consults for Roche, Inc., Merck, Inc., Biogen, Inc., Eisai Inc., GE Healthcare and is on a DSMB for Genentech, Inc. M.M.M. receives unrestricted research grants from Biogen and consults for The Brain Protection Company. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2019. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/ Accessed on June 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, et al. Increasing use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1615–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolla M, Collette L, Blank L, et al. Long-term results with immediate androgen suppression and external irradiation in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer (an EORTC study): a phase III randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CU, Hunt D, McGowan DG, et al. Radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holzbeierlein JM, Castle E, Thrasher JB. Complications of androgen deprivation therapy: prevention and treatment. Oncology (Williston Park). 2004;18:303–309; discussion 310, 315, 319–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson CA, Shanafelt TD, Loprinzi CL. Andropause: symptom management for prostate cancer patients treated with hormonal ablation. Oncologist. 2003;8:474–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez BD, Jim HS, Booth-Jones M, et al. Course and predictors of cognitive function in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen-deprivation therapy: a controlled comparison. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2021–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGinty HL, Phillips KM, Jim HS, et al. Cognitive functioning in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2271–2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH, Rosenzweig KE. No relationship of anti-androgens to Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive disorder in the MedWatch Database. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2018;2:123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alibhai SM, Timilshina N, Duff-Canning S, et al. Effects of long-term androgen deprivation therapy on cognitive function over 36 months in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsden M, Nyborg AC, Murphy MP, et al. Androgens modulate beta-amyloid levels in male rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1052–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdile G, Asih PR, Barron AM, et al. The impact of luteinizing hormone and testosterone on beta amyloid (Abeta) accumulation: animal and human clinical studies. Horm Behav. 2015;76:81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson CJ, Nandy N, Roth AJ. Chemotherapy and cognitive deficits: mechanisms, findings, and potential interventions. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S, Malkowicz SB, et al. Association between androgen deprivation therapy use and diagnosis of dementia in men with prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e196562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, et al. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokmen E, Smith GE, Petersen RC, et al. The short test of mental status. Correlations with standardized psychometric testing. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE, et al. Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies: WAIS-R norms for ages 56 to 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun M, Cole AP, Hanna N, et al. Cognitive impairment in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2018;199:1417–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson CJ, Lee JS, Gamboa MC, et al. Cognitive effects of hormone therapy in men with prostate cancer: a review. Cancer. 2008;113:1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]