Abstract

Innate immune cells can develop exacerbated immunological response and long-term inflammatory phenotype following brief exposure to endogenous or exogenous insults, which leads to an altered response towards a second challenge after the return to a non-activated state. This phenomenon is known as trained immunity (TI). TI is not only important for host defense and vaccine response, but also for chronic inflammations such as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases such as atherosclerosis. TI can occur in innate immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages, NK cells, ECs and non-immune cells such as fibroblast. In this brief review, we analyze the significance of TI in endothelial cells (ECs), which are also considered as innate immune cells in addition to macrophages. TI can be induced by a variety of stimuli including LPS, BCG, and oxLDL, which are defined as risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Furthermore, TI in ECs is functional for inflammation effectiveness and transition to chronic inflammation. Rewiring of cellular metabolism of the trained cells takes place during induction of TI, including increased glycolysis, glutaminolysis, increased accumulation of TCA cycle metabolites and acetyl-CoA production, as well as increased mevalonate synthesis. Subsequently, this leads to epigenetic remodeling, resulting in important changes in chromatin architecture that enables increased gene transcription and enhanced pro-inflammatory immune response. However, TI pathways and inflammatory pathways are separated to ensure memory stays when inflammation undergoes resolution. Additionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) play context-dependent roles in TI. Therefore, TI plays significant roles in endothelial cell and macrophage pathology and chronic inflammation. However, further characterization of TI in ECs and macrophages would provide novel insights into cardiovascular disease pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets.

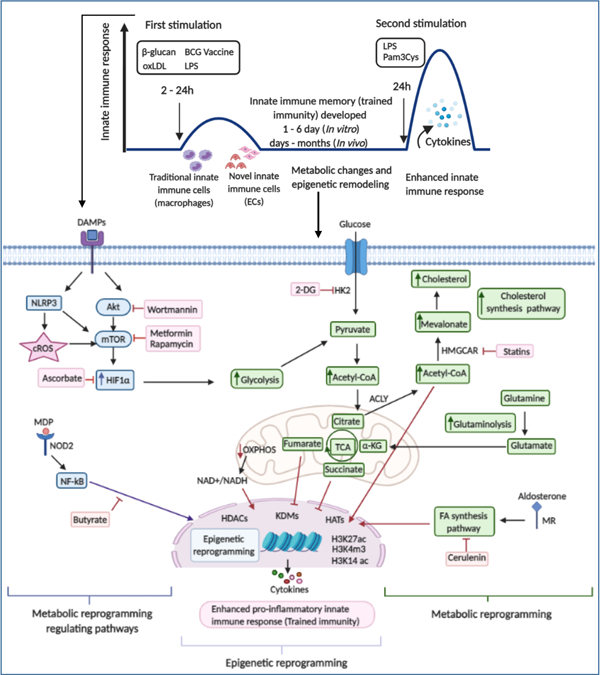

Graphical Abstract

1. Trained immunity inducers are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and other chronic metabolic diseases

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. Sub-endothelial retention of oxidized plasma lipoproteins triggers the recruitment of monocytes, macrophages, T cells, and other immune cells into arteries, suggesting that innate and adaptive immunity contribute to form atherosclerotic plaques1. Dogmatic descriptions of the immune system characterize the innate immune system with monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and endothelial cells (ECs) as the rapid, non-specific branch and the adaptive immune system with T cells and B cells as the delayed but specific arm that coordinates the immune response and provides “memory” of the encounter in the form of memory T cells (Tm)2 for a future exposure to the same pathogen. While this paradigm was mostly accurate, recent discoveries have provided evidence that the innate immune system also has “memory” of past infections/non-infectious stimuli that inform future enhanced immunological responses. Whereas the memory of the adaptive immune system provides specific defenses against a particular pathogen encoded in the genome of a specialized Tm cell type, innate immune memory in all the innate immune cells provides a more robust but non-specific immune response to a future unrelated immunological threat, which is codified within the host’s epigenome3. As innate immune memory is a relatively newly described phenomenon in humans, many terms have been used to describe the process4.

Innate immune memory or trained immunity (TI)5 can be defined as an initial immune response modifying the immune response to a future exposure of an unrelated pathogen (Figures 1A and 1B). This initial “priming” response can either position the innate immune system for an elevated immune response (trained potentiation with increased pro-inflammatory cytokine generation) or a suppressed immune response (trained tolerance)5. These modified immune responses can exist for days to months6, 7. TI can be induced by different stimuli including Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), β-glucan, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and others8–10 (Table 1A)

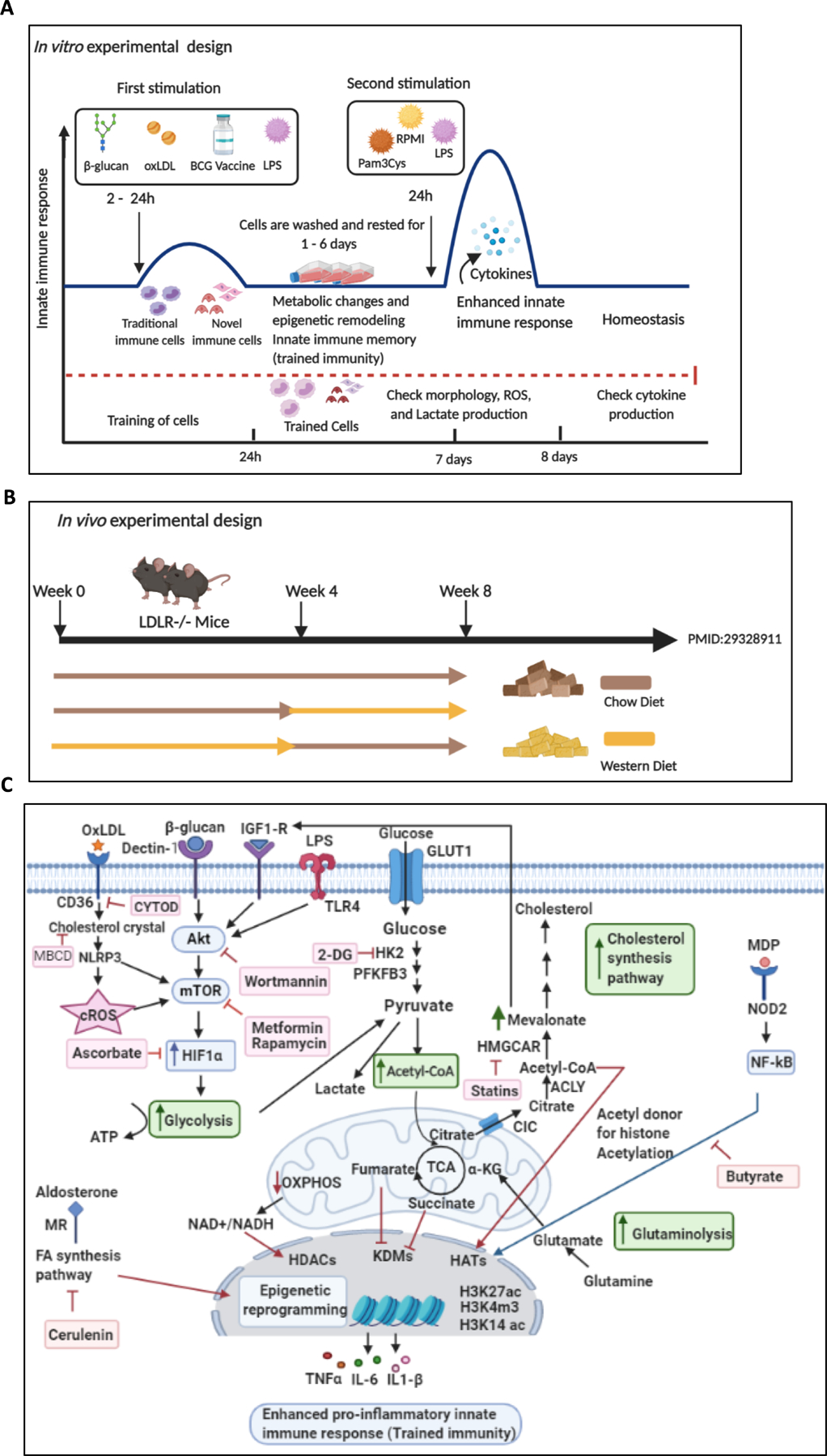

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of trained immunity experimental design in vitro, in vivo, and the complex metabolic pathways involved in trained immunity. A. In vitro induction of trained immunity: Traditional and novel immune cells are trained by β-glucan, oxLDL, LPS, and BCG for 24 hours. Cells are washed twice with PBS and rested in culture media for 24 hours, 3 days, or 6 days, after which the cells are restimulated with LPS or Pam3Cys for 24 hours. Then cytokine productions are measured. B. In vivo induction of trained immunity by a Western diet priming and LPS restimulation. Low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient (LDLR−/−) mice are fed with Western diet for 4 weeks, then, normal chow diet for another 4 weeks. Six hours before sacrifice, mice are injected intravenously with LPS or PBS. C. Overview Figure Showing the Metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming in trained immunity. Trained immunity inducers bind to their receptors in the cell membrane or intracellular receptors, leading to enhanced signaling of the Akt–mTOR–HIF-1α pathway, modifications in metabolic pathways (increased glycolysis, increased acetyl-CoA generation, increased mevalonate synthesis), and epigenetic reprogramming. This results in increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production and enhanced innate immune response (trained immunity). Abbreviation: oxLDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein, BCG: Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, LPS: Lipopolysaccharide, cROS: Cytosolic reactive oxygen species, LDLR−/− mice: Low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice, Akt: Serine/threonine protein kinase, mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin, HIF1: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, 2-DG: 2-deoxyglucose, GLUT1: Glucose transporter 1, HK2: Hexokinase 2, PFKFB3: Phosphofractokinase-2/FBPase isozyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3, Acetyl CoA: Acetyl Coenzyme A, α-KG: α-ketoglutarate, OXPHOS: Oxidative phosphorylation, CIC: Citrate carrier, ACLY: Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-citrate lyase, HMGCAR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase, H3K27ac: Histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation, H3K4m3: Histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation, H3K14ac: Histone 3 lysine 14 acetylation, TNFα: Tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6: Interleukin-6, IL1-β: Interleukin 1-β, NOD2: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2, MDP: Muramyl dipeptide, NF-kB: nuclear factor (NF)-κB, FA: Fatty acid, MR: Mineralocorticoid receptor, HDACs: Histone deacetylase, HATs: histone acetyl transferases, KDM: Histone lysine demethylase. Figure created with BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/user/signin).

Table 1. A.

A schematic summary of training programs induced in different cell types.

| Stimulation | Receptor | Cell type | Training immunity signaling | Metabolic remodeling | Epigenetic remodeling | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-glucan | Dectin-1 | Monocytes BMPCs |

Akt-mTOR-HIF1α IL-1 GM-CSF/CD131 |

Glycolysis Glutaminolysis Mevalonate synthesis |

H3K4me1 H3K4me3 H3K27ac |

25258083 29328908 27866838 |

| BCG | NOD2 | Monocytes BMPCs |

Akt-mTOR, IFN-r, IL-32 | Glycolysis Glutaminolysis Mevalonate synthesis |

H3K9me3 H3K4me3 H3K27ac |

27926861 29328912 29324233 |

| OxLDL | TLR | Monocytes | mTOR dependent ROS | Glycolysis Mevalonate synthesis |

H3K4me3 | 27733422 30723479 |

| LPS | TLR4 | Monocytes | IRAK-M, Tollip,JNK-miR24, ATF7 | Glucose and cholesterol metabolism | H3K4me1 H3K4me3 H3K9me2 H2K27me |

27824038 26322480 |

| Aldosterone | Mineralocorticoid | Monocytes | Fatty acid synthesis pathway | Fatty acid synthesis | H3K4me3 | 31119285 |

| HMGB1 | TLR RAGE |

Splenocytes | IRAK-M | 24089009 26970440 |

||

| LPC | GPCR | Endothelial cells | ROS | Glycolysis Acetyl-CoA generation Mevalonate synthesis |

H3K14ac | 31153039 |

| Fungal Chitin | TLR | Monocytes | - | - | Histone methylation | 26887946 |

| WD | - | BMPCs | NLRP3 IL-1 |

- | 29328911 | |

| CMV | NK cells | SYK PLZF |

- | Methylation | 25786175 25786176 |

|

| Uric acid | - | Monocytes | IL-1β Akt |

- | Histone methylation | 28484006 31853991 |

Abbreviation: HIF1α: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha, BMPCs: Bone marrow progenitor cells, GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, CMV: Cytomegalo-virus, BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, oxLDL: Oxidized low-density lipoprotein, LPS: Lipopolysaccharides, GPCR: G-protein coupled receptor, NOD2: Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2, IFN-γ: Interferon gamma, TLR: Toll-like receptor, IRAK-M: IL-1 Receptor-Associated Kinase M, HMGB1: High mobility group box 1, RAGE: receptor for advanced glycation end-products, LPC: Lysophosphatidylcholine, WD: Western diet, H3K27ac: Histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation, H3K4m3: Histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation, H3K14ac: Histone 3 lysine 14 acetylation, H3K9m2: Histone 3 lysine 9 dimethylation, Akt: Serine/threonine protein kinase, mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin, NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing 3.

TI has not only been identified in myeloid precursors, macrophages and circulating monocytes11, 12, but also in other innate immune and non-immune cells. For example, TI properties have been demonstrated in vascular smooth muscle cells13, ECs14, 15, primed adipose mesenchymal stem cells16, and bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells (HSC)17 contributing to both human auto-inflammatory diseases such as hyper-immunoglobulin D (IgD) syndrome (HIDS)18 and sterile inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis11, 19. These studies have demonstrated that sterile lipid inflammatory mediators prime myeloid precursor cells in the bone marrow. However, what features of sterile lipid inflammatory mediators have as one of the CVD risk factors identified that are similar to infectious agents in eliciting innate immune responses in the cardiovascular system? As we pointed out recently, the common properties of identified CVD risk factors are to elicit innate immune memory (trained immunity) of the cardiovascular system so that the innate immune responses to the risk factor(s) or other non-specific stimuli can be amplified and long lasting20.

2. Trained immunity in endothelial cells is functional for inflammation effectiveness and transition to chronic inflammation

We previously argued that ECs are conditional innate immune cells14, 21. ECs function to regulate vascular permeability, metabolite and waste exchange, and immune cell extravasation into tissue22–25. ECs also express many of the same pattern recognition receptors and cytokines as other profession immune cells such as macrophages24, 26. Importantly, ECs have an immune response modulation (promotion or suppression) functions on both the innate and adaptive immune systems by expressing T cell co-stimulation/immune checkpoint receptors27–29. Proper EC function is so critical that EC dysfunction is the first step towards the inflammatory cascade that leads to the development of CVD22. EC detection of hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hyperhomocysteinemia metabolic danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) leads to the expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules that initiate the recruitment of monocytes and T cells into major arteries leading to atherosclerosis30–37. However, two important questions remain: 1) whether DAMPs-sensing capacities are functionally linked to TI in ECs? And 2) whether pro-atherogenic stimuli make ECs undergo metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming, which leads to TI?

TI has also been characterized in ECs. One such study illustrates that how innate immune potentiation in EC uses the same atherogenic metabolic DAMP38, oxLDL, that elicits innate immune training, similar to that in monocytes, oxLDL-mediated immunologic memory in ECs15. In this study, they demonstrate that oxLDL promotes an increased innate immune cell phenotype (increased cytokine production, increased adhesion molecule expression), switch from oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to glycolysis via metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications downstream protein kinase B (Akt)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling. Other studies have identified oxLDL-mTOR signaling in monocytes, and reported that shear stress triggers hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF1-α) in ECs9, 39–41. Another study characterizes the effects of bacterial endotoxin LPS induced-immune tolerance in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) and the potential use of monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA), a compound similar in structure to LPS, to induce trained tolerance as a potential therapeutics to suppress innate immune inflammation42–44. These results suggest that ECs function as conditional innate immune cells; and that they are the gatekeepers and make decision on trained immunity or trained tolerance that control the progression towards atherosclerosis.

EC are highly heterogeneous despite arising from a common progenitor45. This heterogeneity is reflected by distinctive patterns of inflammation-induced changes in leukocyte recruitment and protein expression between different ECs46, 47. Certain vascular beds including arteries and veins in heart, kidney and lung are more susceptible to the development of inflammation48. For example, EC in certain location in the arterial tree as the aortic arch and carotid arteries are particularly susceptible to atherosclerosis (atherosclerotic prone regions) whereas others such as the distal internal carotid and upper extremity arteries, are usually spared41, 49. Indeed, ECs lining those arteries in the atherosclerotic prone regions characterized by hyper-inflammatory state and probably upregulation of the TI pathways. Furthermore, microvascular ECs inflammation and immune response contributes to hypertension50–52, presumably via TI pathways. Additionally, a growing body of evidence suggests a role for consideration of ECs activation and inflammation as a major contributor to the pathophysiology of venous thromboembolism53, 54. Therefore, the key event in the initiation of venous thromboembolism formation is most likely vein wall inflammation and studies showed that probable association between venous thromboembolism and several other markers of inflammation such as IL-6, MCP1, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha exists55–57. Moreover, microvascular ECs inflammation, hypertension, and thromboembolism have been shown to be associated with COVID-1958, 59 presumably also via TI pathways. Why do ECs need to have TI function? ECs have TI function to achieve the following purposes: 1) making EC sensing of DAMPs more effective; 2) guiding trans-EC migration of monocytes, T cells and other immune cells to the atherogenesis-prone regions of major arteries such aortic sinus in TI-enhanced manners; 3) differentiating CVD risk factors (inducing TI pathways) from non-inflammatory stimuli (not inducing TI pathways), for example, all the 70,926 compounds identified in the foods (https://foodb.ca/compounds) that have potential to get into human blood circulation20; and 4) making inflammation triggered by CVD risk factors become chronic. This conclusion opens exciting new possibilities in targeting EC trained immunity for the treatment of not only CVD, but also for the treatment of other metabolic inflammatory diseases.

3. Reprogramming of bioenergetic metabolic pathways in trained immunity generates compounds for epigenetic memory

The five classical signs of inflammation are heat, pain, redness, swelling and loss of function, in which ECs play essential roles. The processes have to be highly effective in secreting cytokines, recruiting innate immune cells, phagocytosis, cell locomotion, and killing of pathogens or cells, all of which require high energy via bioenergetic metabolic reprogramming4 selected from 2,847 metabolic pathways (https://metacyc.org/)14. To provide the energy needed to function properly, the metabolic processes of the innate immune cells are regulated precisely. Trained immunity is intrinsically linked to changes in cellular bioenergetic metabolism. These metabolic pathways include the glycolytic pathway, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle, acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) generation, and mevalonate pathway, which are closely intertwined, because of shared fuel inputs and the dependence on the products of other pathways to serve as precursors (Figure 1C)18, 60.

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is a major metabolic pathway and plays an important role in biosynthetic pathways. In this pathway, glucose is converted to pyruvate in the cytoplasm and enters into the TCA cycle or fermented into lactate. The “Warburg Effect,” first identified in highly metabolically active cancer cells, has been identified as a key metabolic transition to glycolysis, which is seen in cells undergoing biosynthesis of pro-inflammatory molecules10, 61, 62. Additionally, the transition from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis seen in the Warburg Effect63 is also an important metabolic change in TI. This cellular metabolic switch has been demonstrated in β-glucan- and BCG-induced, innate immune training in monocytes10, 64, 65. In vitro studies reported that β-glucan-trained human monocytes have dramatically reduced oxygen consumption and increased glucose consumption and lactate production66. Additionally, in vivo studies reported that isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells trained with BCG induce-TI associated with upregulation of the key enzymes involved in glycolysis pathways such as hexokinase 2 (HK2) and phosphofructokinase platelet (PFKP)60. The molecular mechanism underlying β-glucan and BCG induced-TI have been outlined in monocyte in vitro studies. β-glucan and BCG training promote a metabolic transition to glycolysis via the pathway of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α)66, 67. Pharmacological inhibition of Akt-mTOR-HIF1α pathway or glycolysis pathway using wortmannin, rapamycin, and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (Table 1B), as well as gene knockout of HIF1α in myeloid cells reverses the pro-inflammatory phenotype in trained innate cells66.

Table 1B.

Trained-immunity-regulating pathway inhibitors.

| 1st stimulus | 2nd stimulus | Inhibitor | Function | Effect on trained immunity | PMID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I- Inhibition of signaling pathways | |||||

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Wortmannin | Akt inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Rapamycin | mTOR inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

AICAR | mTOR inhibitor | Inhibits trained immunity | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Metformin | AMPK inhibition | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Ascorbate | HIF1α inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 |

| LPS (200 ng/ml) for 6 h | OxLDL (50 μg/mL) for 24 h | Z-VAD-fmk | NLRP3 activation inhibitor | Inhibits IL-1β secretion | 23812099 |

| LPS (200 ng/ml) for 6h | OxLDL (50 μg/mL) for 24 h | MβCD | Cholesterol crystal formation inhibitor | inhibits the cholesterol crystals and IL-1β secretion | 23812099 |

| II- Inhibition of metabolic pathways | |||||

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

2-DG | Inhibits HK2 (glycolytic rate limiting step) | Inhibit trained immunity | 27926861 25258083 |

| OxLDL (10 μg/mL) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) | 3PO | Inhibit glycolytic enzyme PFKFB3 | Inhibit trained immunity | 32350546 |

| β-glucan (5 μg/ml), oxLDL (10 μg/ml), (R)-mevalonic acid (100–1000 μM), BCG (5 μg/ml) | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 μg/ml) |

fluvastatin | HMGCAR inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 29328908 |

| β-glucan (5 μg/ml), oxLDL (10 μg/ml), (R)-mevalonic acid (100–1000 μM), BCG (5 μg/ml) |

LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 μg/ml) |

6-fluoromeval-onate | Mevalonate-pyrophosphate decarboxylase inhibitor | Enhance trained immunity | 29328908 |

| LPS (200 ng/ml) for 6 h | OxLDL (50 μg/mL) for 24 h | CYTOD | CD36 inhibitor | inhibit formation of cholesterol crystals and IL-1β secretion | 23812099 |

| Aldosterone for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 μg/ml) |

Cerulenin | FAS inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 31119285 32241223 |

| III- Inhibition of epigenetic reprogramming | |||||

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

MTA | Non-selective Methyltransferase inhibitor | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 29328908 30380404 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

ITF (ITF2357) | HDACi | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Cyproheptadine | Set7 methyltransferase inhibitor | Inhibit glycolysis | 25258083 |

| β-glucan (10 μg/ml) for 24 h | LPS (10 ng/ml) Pam3Cys (10 g/ml) |

Resveratrol | HDAC/sirtuins activator | Inhibit trained immunity | 25258083 30380404 |

| - | - | UMLILO | Inhibit H3K4me3 epigenetic priming | Inhibit trained immunity | 30733945 |

Abbreviation: 2-DG: 2-deoxyglucose, HK2: Hexokinase2, PFKFB3: Phosphofractokinase-2/FBPase isozyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3, HMGCAR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase, IL1-β: Interleukin 1-β, HDACi: Histone deacetylase inhibitor, AICAR: Adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) activator, Z-VAD-fmk: Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone, MβCD: Methyl-β-cyclodextrin, 3PO: 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one, CYTOD: Cytochalasin D, FAS: Fatty acid synthetase, MTA: 5′-Methylthioadenosine, UMLILO: Upstream Master LncRNA of the inflammatory chemokine Locus.

Pro-atherogenic lipids, such as oxLDL and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), have been shown to drive TI phenotypes in innate immune cells as well as ECs9, 20, 68–71. Training of monocytes with oxLDL induces TI and increases glycolysis, however, inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG and inhibition of the inducible PFK-2/FBPase isozyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3) prevent development of TI72. Genetic variation in PFKFB3 and PFKP genes is associated with the increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and inteleukin-6 (IL-6) production ex vivo upon training with oxLDL73. Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) primed with oxLDL exhibit increased glycolysis and lactate production15. Similarly, the TI phenotype in oxLDL-primed HAECs is reversed upon treatment with mTOR inhibitors (Torin1), glycolysis inhibitors 3-(3-pyridinyl)-1-(4-pyridinyl)-2-propen-1-one (3PO) and HIF1α inhibitors (KC7F2)15.

Tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) for citrate-Acetyl-CoA generation and fumarate accumulation

Another important metabolic event in trained immune cells is the TCA cycle’s anabolic repurposing towards synthesizing cholesterol from acetyl-CoA and citrate. The TCA cycle in mitochondria represents a critical pathway of cellular energy metabolism resulting in the oxidation of different substrates, including pyruvate generated from glycolysis in the cytosol18.

In addition to the transition from OXPHOS to glycolysis, β-glucan trained macrophages have increased levels of glycolysis-related metabolites (including Acetyl-CoA). The TCA cycle-related metabolites such as citrate, succinate, malate, and fumarate are increased in trained monocytes due to the partial shutdown of the TCA cycle66. Citrate can be generated from glycolysis via pyruvate or generated from glutamine (glutaminolysis) and converted into α-ketoglutarate to enter the TCA cycle74, 75. Then citrate is transported from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm by the citrate carrier (CIC), is converted into acetyl-CoA by adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-citrate lyase (ACLY)76 and used as a precursor in mevalonate/cholesterol biosynthesis pathway and lipogenesis pathway. Moreover, ACLY-catalyzed acetyl-CoA is a key determinant of cellular protein acetylation and used as an acetyl donor for histone acetylation, regulating the expression of several genes77. Importantly, acetyl-CoA generated from both glycolysis and glutamine can induce histone acetylation of genes of glycolytic enzymes, including; hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase (PFK), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) resulting in increased glycolysis78. Additionally, ACLY acts as a key enzyme in macrophage inflammatory response. Different inflammatory stimuli including LPS, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and TNF-α induce ACLY expression in immune cells79.

Metabolomics and transcriptomic studies of β-glucan trained immune cells showed that these trained cells increase accumulation of the TCA cycle metabolite fumarate80. Several lines of evidence showed that succinate and fumarate accumulation is associated with stabilization of HIF-1α leading to increased glycolysis and IL-1β production81, 82. Furthermore, fumarate accumulation leads to epigenetic reprogramming by inhibiting lysine-specific histone demethylase 5 (KDM5)80. Furthermore, increased glutamine metabolism (glutaminolysis) is one of the important metabolic changes in macrophages trained with BCG and β-glucan to produce more citrate for Acetyl-CoA generation in the cytosol60, 80. Notably, the glutamine pathway inhibition by the glutaminase inhibitor, Bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES) inhibits β-glucan and BCG induced TI in vitro and in vivo60, 80.

Mevalonate synthesis pathway

The cholesterol biosynthesis is an effector molecule involved in inflammatory responses83. Acetyl-CoA generated from the TCA cycle in the cytoplasm can enter the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway and generate cholesterol using the enzyme, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGCAR), which is the rate-limiting step in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Cholesterol plays a critical role in the inflammatory function of different immune cells. Lipid rafts in the cellular membrane are important for inflammatory signal transduction pathways83. Furthermore, cholesterol accumulation in monocytes/macrophages play a key role in the acceleration of atherosclerosis84. Increased cholesterol synthesis is an important hallmark of β-glucan trained monocytes. In fact, this is accomplished not by cholesterol biosynthesis but rather by an accumulation of the upstream metabolite mevalonate18. As highlighted earlier, Akt-mTOR-HIF1α drives metabolic reprogramming through the mevalonate pathway, which is considered the underlying mechanism that induces TI. In addition, β-glucan trained macrophages show an upregulation of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis pathways. Of note, increased cholesterol synthesis is critical for the β-glucan-induced training of mature myeloid cells and the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs)12.

The functions of the mevalonate synthesis pathway in TI can be summarized: first, human monocytes exposed to mevalonate for 24 hours increase cytokine production and induce TI associated with increased aerobic glycolysis and enrichment of histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3) on the promoters of several cytokine genes18. Second, inhibition of the mevalonate pathway by using statins (HMGCAR inhibitor) significantly reduces TI induced by oxLDL and β-glucan in vitro and in vivo18, 85 presumably by a negative feedback to decrease Acetyl-CoA generation for histone acetylation. Third, pharmacological inhibition studies demonstrated that mevalonate enhances TI via activation of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1-R) and subsequent stimulation of mTOR signaling and glycolysis pathway by a positive feedback loop18.

Multiple levels of experimental evidence showed the in vitro pharmacological inhibitors of mevalonate pathway, glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and pharmacological blockers of histone methyltransferases could ameliorate induction of TI. Furthermore, in vivo studies using mouse models have confirmed these results80. These results would allow the development of novel pharmacological strategies to inhibit TI. However, future extensive studies and further elucidation of the mechanism of TI in endothelial cells will provide an exciting novel prospect for the development of pharmacological strategies to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic diseases.

4. Epigenetic reprogramming is formed for enhancement of cytokine responses when encountering subsequent specific or non-specific challenges

The epigenetic reprogramming of trained immune cells is driven, at least in part, by a rewiring of intracellular metabolic pathways86. A switch from OXPHOS to increased glycolysis is key for the development of the trained phenotype69. In addition, increased glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation can inhibit histone demethylase KDM5 and affects histone methylation80. β-glucan induced TI depends on the intracellular accumulation of mevalonate and the subsequent activation of the IGF-1 receptor18. Therefore, epigenetic modification plays a critical role in mediating TI. During the TI process, the first stimulations, such as BCG, oxLDL or LPS, rewrite the epigenetic modifications of inflammatory cytokines’ enhancers or promotors in innate immune cells. After the epigenetic modification, second stimuli induce high cytokine production, activate intracellular signaling molecules, and enhance inflammatory response87. These epigenetic modification in TI includes histone methylation and acetylation88, 89. However, the epigenetic modifications induced by different stimuli are variable in mechanisms and cell types of TI.

BCG vaccination promotes the binding of H3K4me3 at the promoters of inflammatory genes encoding TNFα, IL6, and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)90. Besides H3K4me3, BCG significantly augments IL-1β production via histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) enrichment and protects against virus infection in monocytes91. In addition to enrichment of histone modification, studies also found that BCG leads to decreased H3K9me3, a repressor mark, and enhances TI response60. Furthermore, β-glucan priming increases cytokine production by enrichment of H3K4me3 but not H3K27me3 in monocytes92 via an increased levels of long non-coding RNAs in macrophage93. The top 500 genes, induced by H3K4me3 in β-glucan treatment, are related to the production of cytokines and chemokines in atherosclerosis progression9. To clearly study the relationship of H3K4me3 with TI, studies found that inhibition of histone demethylase KDM5 by fumarate accumulation80 significantly increases the levels of H3K4me3, suggesting that the TCA cycle product fumarate plays an important role in β-glucan mediated TI9. In addition to H3K4me3, β-glucan also increases H3K4me1 and H3K27ac in monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and TI67.

oxLDL, an established risk factor for CVD and chronic kidney disease, is also critical for TI induction. oxLDL priming significantly increases the enrichment of H3K4me3 at the promoters or enhancers of pro-atherogenic cytokines and chemokines9 as well as H3K27ac at the promoters of IL-6 and IL-8 via mTOR-HIF1α signaling in ECs15. The oxLDL induced TI is abrogated by non-specific histone methyltransferase inhibitor. Besides this, inhibition of histone methylation by pan-methyltransferase inhibitor 5’-methylthioadenosine (MTA) blocks the phenotype of TI induced by β-glucan94 and BCG92. LPC is another risk factor and DAMP for atherosclerosis36 has been reported to induce TI enzymes via H3K14ac in HAECs20.

Additionally, aldosterone, the main mineralocorticoid hormone, induces the gene expressions related to fatty acid metabolism and pro-inflammatory cytokines production via H3K4me3 enrichment in macrophage95. Super-low dose LPS has been shown to induce TI in vivo and in vitro. LPS promotes enhancer activities in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac and TI in HSCs96 and macrophage97. Studies reported that the epigenetic changes could maintain 12 weeks, which are mediated by CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) transcription factor family in LPS-induced TI96. In addition to active epigenetic reprograming, LPS also induces TI by inhibiting histone 3 lysine 9 di-methylation (H3K9me2), a suppressive histone modification, via stress-response transcription factor ATF7 phosphorylation-mediated mechanism98. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) also induces TI via DNA hyper-methylation at promoters of altered cytokines in natural killer (NK) cells99.

Based on these publications, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, H3K14ac, and H3K4m1 have been reported to participate in most stimuli-induced TI in different cell types including ECs. In addition, future work is needed to identify other stimuli involved in TI and epigenetic reprogramming in ECs.

5. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play context-dependent roles in trained immunity

Cellular metabolic pathways and signaling molecules are significantly correlated to epigenetic rewriting in TI. We recently proposed that ROS systems are a new integrated network for sensing homeostasis and alarming stresses in organelle metabolic process100. Previous studies reported that ROS production can be regulated by circular RNAs and associated with different cardiovascular metabolic inflammation101. In addition, ROS generated in metabolic processes are reported to participate in the process of TI and the metabolic reprogramming during immune responses leads to excessive ROS production102. We previously reported that ROS mediate LPC-induced TI enzyme transcription in HAECs20, 100 and that IL-35 can downregulate three ROS promoters and upregulate one ROS attenuator103. In addition, ROS generation is increased by BCG and oxLDL priming in monocytes8. Studies further reported that oxLDL-induced ROS production via mTOR signaling plays critical role in promoting TI71. To further study ROS production’s function in TI in vivo, mice are first trained with BCG followed by a second stimulation with a type of ROS hypochlorous (HOCL). After ROS stimulation, the productions of cytokines and chemokines, such as C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), C-X-C receptor type 4 (CXCR4), lymphocyte antigen 6 (Ly6C) and C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) are significantly increased104. However, other publications reported that β-glucan decreases ROS production and increases mTOR signaling in trained monocytes8. Additionally, studies reported that mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) production inhibits the transcriptional factors and gene expressions, but not epigenetic remodeling in TI105. Therefore, further studies are needed for the detailed role and mechanisms for ROS production and TI in ECs.

ROS are the upstream direct activator of NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)-caspase-1 inflammasome, which is an important mediator of TI. The nucleotide-binding site domain in NLRP3 is highly sensitive to ROS100. After tightly binding with, the NLRP3 is activated and promotes the progression of TI. In addition, oxLDL and extracellular ATP promote the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and induction of TI via H3K4me1, H3K4me3 and H3K27ac enrichment9. Thus, the ROS-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway may be the potential regulating mechanism of TI. However, the other detailed mechanisms have been less reported than the ROS-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, and further studies are needed. Taken together, ROS play context-dependent roles in TI.

6. Trained immunity pathways and inflammatory pathways are separated to ensure memory stays when inflammation undergoes resolution

Adaptive immunological memories are carried out by special functional cell populations, memory T2 and memory B lymphocytes, which are separated from effector T cells/B cells89. Thus, this mechanism ensures that the robust immune responses to dominant pathogens are carried out by effector cells. In contrast, immune memories are carried out by a small number of memory cells with high antigen specificities. However, an important question remains whether this important mechanism exists in innate immune cells. We previously found out that innate immune memory pathway and effector pathway are separated in LPC-trained ECs; and that LPC-induced H3K14ac binds more TI gene genomic regions (78.95%) than that of effector genes (43.12%)20. Another publication reported that epigenetic reprogramming-modulated innate immune memory is separated from the transcriptional factors-regulated innate immune effector pathways in HAECs. Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-35 and IL-10, inhibit the effector pathways in LPC-induced TI in ECs, whereas having no inhibition affects the expression of memory pathway genes105. Further studies are needed to determine the detailed mechanisms of separation of memory and effector pathways in TI.

7. Trained immunity plays significant roles in endothelial pathology and chronic inflammation

Infections

Immune memory is a defining feature of the acquired immune system. However, reprogramming of innate immunity can also result in enhanced responsiveness to subsequent triggers, which forms the basis on which chronic inflammatory diseases develop4. ECs have been documented the existence of non-specific characteristics of innate immunity when exposed to exogenous or endogenous stimuli14. Dengue viruses cause two severe diseases that alter vascular fluid barrier functions, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome106. ECs are critical targets of dengue virus infection that can contribute to viremia, elicit immune-enhancing responses via high-level induction and secretion of activating and recruiting cytokines by immune cells107. The immune memory of prior infection of the dengue virus could provide protection for 2–3 months. When short-term cross-protection wanes, patients with secondary infections (not limited to dengue virus) are at higher risk of severe disease than patients without prior infection108, suggesting the innate immune training on ECs may have harmful effects on how the immune system responds to subsequent same or other pathogen invasions109. Based on these findings, several trials are currently underway to determine whether BCG can help prevent the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)110.

Association between infections and cardiovascular diseases

Epidemiological evidence indicates that TI links infection and CVD111, 112. Impaired anti-coagulant function and expression of the endothelium genes upon infection with influenza viruses or other respiratory viruses have been linked to a risk of myocardial infarction beyond the short-term post-infection period113. Prior instances of bacteremia and sepsis also substantially increase the 5-year risk of cardiovascular events. Endothelial dysfunction and pro-coagulant changes in the blood provide a biological basis for the association114, 115. The strength and time-related patterns of the association between infections and increased risk of cardiovascular events suggest a causal relationship, that the associations are stronger and last longer when the infections are severe111. Indeed, rather than exposure to specific pathogens, the accumulated non-specific infectious burdens, including infections of Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), are associated with future development of atherosclerosis116–118. A longitudinal population-based study found that severe early life infections are associated with sub-clinical atherosclerosis in adulthood119, 120. Regardless of the induction of a systemic inflammatory response and activation of the immune system, exposure to pathogens correlates with local activation of ECs and the appearance of pro-coagulant activity, leading to endothelial dysfunction. In addition to the atherogenic phenotype of trained macrophages, enhanced adhesive markers and cytokine production capacity in trained ECs also indicate that the TI protects against re-infections but may accelerate the development of chronic inflammation such as atherosclerosis112.

Other than microbial products, endogenous sterile stimuli could trigger TI in multiple clinical scenarios. In the atherosclerosis-prone mice model, Western-type diet- induced systemic inflammations contribute to the enhanced responses to subsequent LPS stimulation68. The transcriptional and epigenetic reprogramming of circulating monocytes and their bone marrow myeloid progenitor cells devote to the TI phenotype, which persists even after the mice had been switched to a normal chow diet, regardless of circulating cholesterol levels and systemic inflammatory markers returning to normal. We previously demonstrated that ECs also underwent transcriptional and epigenetic alterations upon LPC stimulation in vitro and Western diet feeding in vivo121. The changes of a group of enzyme genes lasted even when the endothelial activation markers are obstructed by the administration with anti-inflammation cytokines, suggesting endogenous sterile stimuli induced immune memory could also be built-in ECs105.

Ischemia/reperfusion injury

Organ transplantation has been investigated as another clinical scenario, in which endogenous sterile stimuli could trigger TI in myeloid cell122. Meanwhile, hypoxia/ischemia as a stimulus for TI has been hypothesized123. Endothelial dysfunction plays a significant role in ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury in multiple organs124–126, however, it could be prevented by ischemic conditioning with a protective intervention based on limited intermittent periods of ischemia and reperfusion127. The molecular mechanisms and signal transduction reprogramming including less ROS production, reduced neutrophils recruitment, and diminished inflammatory reactions during the pre-conditioning process indicate the TI characteristics in ECs128, 129. In the context of endothelial training in I/R injury, low-dose LPS pre-treatment could also downregulate the expression of endothelial-cell adhesion receptors, hence alleviate neutrophil invasion into the tissues130.

Recently, we have reported that ischemic pre- and post-conditioning induce upregulation of the canonical and non-canonical inflammasome regulators and TI regulators131. In addition, ischemic pre-conditioning has been demonstrated to alter the brain’s epigenetic profile from ischemic intolerance to ischemic tolerance132. Meanwhile, the miRNA transcriptome changes have also been observed to be involved in the epigenetic reprogramming in the brain ischemic tolerance133, 134. As the induction of miR-15a expression has been experimentally verified to contribute to ischemic endothelial cell damage functionally, the TI phenotype in ECs during the ischemic pre-conditioning may provide neuroprotective roles in later ischemia injuries135.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking (CS)-induced EC damage and endothelial dysfunction seem to be dose-related and contribute to vascular injury, atherogenesis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and increased CVD risk136–138 presumably via increasing TI. Smoking cessation leads to prolonged improvements in endothelial function139, 140 presumably by inhibiting TI. During this process, epigenetic alterations have been demonstrated to play important roles in the specificity and duration of gene transcription141, 142. Indeed, the modification of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) has been evidenced to mediate the disruption of lung endothelial barrier integrity after CS exposure, enhancing the susceptibility to following acute lung injury143. Besides, protein arginine methyltransferase 6 (PRMT6) has been identified in mediating CS-induced apoptosis and inflammation in HUVECs; and modulating this methyltransferase has been demonstrated to be associated with HIV-1 infectivity144 and lung tumor progression145. Taken together, those TI findings may explain the enhancement of CS-induced endothelial impairment to the development of AIDS and tumorigenesis146.

Conclusion

The complexity of the immune system remains at the heart of both infectious and sterile inflammatory diseases. In the case of cardiovascular diseases, the inflammatory response starts with endothelial cell activation147, 148, which coordinates the subsequent leukocyte infiltration. In this context, endothelial cells function as conditional innate immune cells. Recent studies have shown that innate immune memory (trained immunity) is a feature of monocytes, macrophages, NK cells and endothelial cells149, 150. Taken together, these studies support our argument that endothelial cells, in their capacity as conditional innate immune cells with TI function, are the gatekeepers that control the initiation and progression of cardiovascular disease, including atherosclerosis.

Endothelial cells are primed for a potentiated innate immune response common driver of atherosclerosis. Recent studies have demonstrated how the canonical atherogenic DAMP, oxLDL, elicits innate immune training in endothelial cells via 1) increased cytokine and adhesion molecule expression production, 2) a metabolic switch from OXPHOS to glycolysis, 3) epigenetic modifications of pro-inflammatory genes, and 4) ATK-mTOR-HIF1α signaling. Furthermore, changes in shear stress at atheroprone sites in the vasculature have shown key features of trained immunity including 1) upregulation of glycolysis, 2) histone modifications, and 3) HIF1α signaling41.

These conclusions open exciting new possibilities in targeting EC trained immunity for the treatment of not only cardiovascular disease but also for the treatment of other metabolic and inflammatory diseases. The regulation of trained innate immunity may provide new insights and therapeutic targets in various disease contexts151. Promoting trained immunity is beneficial for preventing diseases, for example, using the BCG vaccine for children after birth can reduce child morbidity and mortality152, and can be used as immunotherapies in the treatment of various cancers such as lymphomas, leukemia153, melanomas154, and bladder cancer155, 156. On the other hand, potentiating TI could lead to persistent non-resolving vascular inflammation and chronic inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis. TI inducers such as oxLDL, LPS, and a Western-type diet induce intense inflammatory responses and epigenetic reprogramming, leading to exacerbate atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases3, 60, 68. Therefore, promoting the reverse of trained immune potentiation, a phenomenon known as trained immune tolerance has potential therapeutic uses. Endothelial cell tolerance to LPS challenge induced by MPLA characterizes the effects of LPS induced-immune tolerance in HUVEC and the potential use of MPLA, a compound similar in structure to LPS, to induce trained tolerance as a potential therapeutic to suppress innate immune inflammation44. Further studies are required to elucidate the molecular underpinnings driving endothelial cell TI and their roles in human inflammation and disease.

Highlights.

Innate immune cells can develop exacerbated immunological response after exposure to endogenous or exogenous insults, which phenomenon as trained immunity (TI).

TI can occur in innate immune cells such as monocytes/macrophages, NK cells, and ECs.

TI inducers are risk factors for CVD and other metabolic diseases

TI characterized by metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modification.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play context-dependent roles in TI.

Acknowledgements

C. Drummer IV, F. Saaoud, Y. Shao, Y. Sun, K. Xu, Y. Lu carried out the primary literature search and drafted the manuscript. Others provided material input and helped revised the manuscript. X. Yang conceived the study and provided field expertise. We are very grateful to Dr. Esther Lutgens for the invitation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Sources of funding

Our research activities are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL131460, HL132399, HL138749, HL147565, HL130233, DK104116, and DK113775). The content in this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- TI

Trained immunity

- OxLDL

Oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- DAMPs

Danger-associated molecular patterns

- LPC

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- HIF1-α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α

- HUVECs

Human umbilical vein ECs

- HAECs

Human aortic endothelial cells

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-coenzyme A

- ACLY

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-citrate lyase

- H3K4me3

Histone 3 lysine 4 tri-methylation

- H3K27ac

Histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Gistera A, Hansson GK. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:368–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stark R, Wesselink TH, Behr FM, Kragten NAM, Arens R, Koch-Nolte F, van Gisbergen K, van Lier RAW. T rm maintenance is regulated by tissue damage via p2rx7. Sci Immunol 2018;3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riksen NP, Netea MG. Immunometabolic control of trained immunity. Mol Aspects Med 2020:100897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Netea MG, Dominguez-Andres J, Barreiro LB, Chavakis T, Divangahi M, Fuchs E, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Mhlanga MM, Mulder WJM, Riksen NP, Schlitzer A, Schultze JL, Stabell Benn C, Sun JC, Xavier RJ, Latz E. Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:375–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boraschi D, Italiani P. Innate immune memory: Time for adopting a correct terminology. Front Immunol 2018;9:799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Benn CS, Joosten LA, Jacobs C, van Loenhout J, Xavier RJ, Aaby P, van der Meer JW, van Crevel R, Netea MG. Long-lasting effects of bcg vaccination on both heterologous th1/th17 responses and innate trained immunity. J Innate Immun 2014;6:152–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassone A. The case for an expanded concept of trained immunity. mBio 2018;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekkering S, Blok BA, Joosten LA, Riksen NP, van Crevel R, Netea MG. In vitro experimental model of trained innate immunity in human primary monocytes. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2016;23:926–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Riksen NP. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34:1731–1738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten LA, Jacobs C, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JW, van Crevel R, Netea MG. Bcg-induced trained immunity in nk cells: Role for non-specific protection to infection. Clin Immunol 2014;155:213–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekkering S, van den Munckhof I, Nielen T, Lamfers E, Dinarello C, Rutten J, de Graaf J, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Gomes ME, Riksen NP. Innate immune cell activation and epigenetic remodeling in symptomatic and asymptomatic atherosclerosis in humans in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2016;254:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitroulis I, Ruppova K, Wang B, Chen LS, Grzybek M, Grinenko T, Eugster A, Troullinaki M, Palladini A, Kourtzelis I, Chatzigeorgiou A, Schlitzer A, Beyer M, Joosten LAB, Isermann B, Lesche M, Petzold A, Simons K, Henry I, Dahl A, Schultze JL, Wielockx B, Zamboni N, Mirtschink P, Coskun U, Hajishengallis G, Netea MG, Chavakis T. Modulation of myelopoiesis progenitors is an integral component of trained immunity. Cell 2018;172:147–161 e112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnack L, Sohrabi Y, Lagache SMM, Kahles F, Bruemmer D, Waltenberger J, Findeisen HM. Mechanisms of trained innate immunity in oxldl primed human coronary smooth muscle cells. Front Immunol 2019;10:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao Y, Saredy J, Yang WY, Sun Y, Lu Y, Saaoud F, Drummer Ct, Johnson C, Xu K, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Vascular endothelial cells and innate immunity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020;40:e138–e152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sohrabi Y, Lagache SM, Voges VC, Semo D, Sonntag G, Hanemann I, Kahles F, Waltenberger J, Findeisen HM. Oxldl-mediated immunologic memory in endothelial cells. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu GY, Liu Y, Lu Y, Qin YR, Di GH, Lei YH, Liu HX, Li YQ, Wu C, Hu XW, Duan HF. Short-term memory of danger signals or environmental stimuli in mesenchymal stem cells: Implications for therapeutic potential. Cell Mol Immunol 2016;13:369–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Kampen E, Jaminon A, van Berkel TJ, Van Eck M. Diet-induced (epigenetic) changes in bone marrow augment atherosclerosis. J Leukoc Biol 2014;96:833–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, Kourtzelis I, van der Heijden C, Li Y, Popa CD, Ter Horst R, van Tuijl J, Netea-Maier RT, van de Veerdonk FL, Chavakis T, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM, Stunnenberg H, Riksen NP, Netea MG. Metabolic induction of trained immunity through the mevalonate pathway. Cell 2018;172:135–146 e139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saaoud F, Wang J, Iwanowycz S, Wang Y, Altomare D, Shao Y, Liu J, Blackshear PJ, Lessner SM, Murphy EA, Wang H, Yang X, Fan D. Bone marrow deficiency of mrna decaying protein tristetraprolin increases inflammation and mitochondrial ros but reduces hepatic lipoprotein production in ldlr knockout mice. Redox Biol 2020:101609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Y, Sun Y, Drummer, Nanayakkara GK, Shao Y, Saaoud F, Johnson C, Zhang R, Yu D, Li X, Yang WY, Yu J, Jiang X, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang X. Increased acetylation of h3k14 in the genomic regions that encode trained immunity enzymes in lysophosphatidylcholine-activated human aortic endothelial cells - novel qualification markers for chronic disease risk factors and conditional damps. Redox Biol 2019;24:101221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yin Y, Li X, Sha X, Xi H, Li Y-F, Shao Y, Mai J, Virtue A, Lopez-Pastrana J, Meng S. Early hyperlipidemia promotes endothelial activation via a caspase-1-sirtuin 1 pathway. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2015;35:804–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao Y, Cheng Z, Li X, Chernaya V, Wang H, Yang XF. Immunosuppressive/anti-inflammatory cytokines directly and indirectly inhibit endothelial dysfunction--a novel mechanism for maintaining vascular function. J Hematol Oncol 2014;7:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davidson SM. Endothelial mitochondria and heart disease. Cardiovasc Res 2010;88:58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mai J, Virtue A, Shen J, Wang H, Yang XF. An evolving new paradigm: Endothelial cells--conditional innate immune cells. J Hematol Oncol 2013;6:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston KJ, Rom I, Vrakas C, Landesberg G, Etwebi Z, Muraoka S, Autieri M, Eguchi S, Scalia R. Postprandial activation of leukocyte-endothelium interaction by fatty acids in the visceral adipose tissue microcirculation. Faseb j 2019;33:11993–12007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez-Pastrana J, Ferrer LM, Li YF, Xiong X, Xi H, Cueto R, Nelson J, Sha X, Li X, Cannella AL, Imoukhuede PI, Qin X, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang XF. Inhibition of caspase-1 activation in endothelial cells improves angiogenesis: A novel therapeutic potential for ischemia. J Biol Chem 2015;290:17485–17494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedke T, Pretsch L, Karakhanova S, Enk AH, Mahnke K. Endothelial cells augment the suppressive function of cd4+ cd25+ foxp3+ regulatory t cells: Involvement of programmed death-1 and il-10. J Immunol 2010;184:5562–5570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupnick AS, Gelman AE, Barchet W, Richardson S, Kreisel FH, Turka LA, Colonna M, Patterson GA, Kreisel D. Murine vascular endothelium activates and induces the generation of allogeneic cd4+25+foxp3+ regulatory t cells. J Immunol 2005;175:6265–6270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen H, Wu N, Nanayakkara G, Fu H, Yang Q, Yang WY, Li A, Sun Y, Drummer Iv C, Johnson C, Shao Y, Wang L, Xu K, Hu W, Chan M, Tam V, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang X. Co-signaling receptors regulate t-cell plasticity and immune tolerance. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2019;24:96–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson C, Drummer Ct, Virtue A, Gao T, Wu S, Hernandez M, Singh L, Wang H, Yang XF. Increased expression of resistin in microrna-155-deficient white adipose tissues may be a possible driver of metabolically healthy obesity transition to classical obesity. Front Physiol 2018;9:1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Virtue A, Johnson C, Lopez-Pastrana J, Shao Y, Fu H, Li X, Li YF, Yin Y, Mai J, Rizzo V, Tordoff M, Bagi Z, Shan H, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang XF. Microrna-155 deficiency leads to decreased atherosclerosis, increased white adipose tissue obesity, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A novel mouse model of obesity paradox. J Biol Chem 2017;292:1267–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xi H, Zhang Y, Xu Y, Yang WY, Jiang X, Sha X, Cheng X, Wang J, Qin X, Yu J, Ji Y, Yang X, Wang H. Caspase-1 inflammasome activation mediates homocysteine-induced pyrop-apoptosis in endothelial cells. Circ Res 2016;118:1525–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang D, Jiang X, Fang P, Yan Y, Song J, Gupta S, Schafer AI, Durante W, Kruger WD, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocysteinemia promotes inflammatory monocyte generation and accelerates atherosclerosis in transgenic cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. Circulation 2009;120:1893–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, Fang P, Jiang X, Nelson J, Moore JK, Kruger WD, Berretta RM, Houser SR, Yang X, Wang H. Severe hyperhomocysteinemia promotes bone marrow-derived and resident inflammatory monocyte differentiation and atherosclerosis in ldlr/cbs-deficient mice. Circ Res 2012;111:37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang P, Li X, Shan H, Saredy JJ, Cueto R, Xia J, Jiang X, Yang XF, Wang H. Ly6c(+) inflammatory monocyte differentiation partially mediates hyperhomocysteinemia-induced vascular dysfunction in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019;39:2097–2119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Li YF, Nanayakkara G, Shao Y, Liang B, Cole L, Yang WY, Li X, Cueto R, Yu J, Wang H, Yang XF. Lysophospholipid receptors, as novel conditional danger receptors and homeostatic receptors modulate inflammation-novel paradigm and therapeutic potential. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2016;9:343–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu M, Saredy J, Zhang R, Shao Y, Sun Y, Yang WY, Wang J, Liu L, Drummer Ct, Johnson C, Saaoud F, Lu Y, Xu K, Li L, Wang X, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Approaching inflammation paradoxes-proinflammatory cytokine blockages induce inflammatory regulators. Front Immunol 2020;11:554301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin Y, Pastrana JL, Li X, Huang X, Mallilankaraman K, Choi ET, Madesh M, Wang H, Yang XF. Inflammasomes: Sensors of metabolic stresses for vascular inflammation. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2013;18:638–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D, Huang RT, Hamanaka RB, Krause M, Oh MJ, Kuo CH, Nigdelioglu R, Meliton AY, Witt L, Dai G, Civelek M, Prabhakar NR, Fang Y, Mutlu GM. Hif-1alpha is required for disturbed flow-induced metabolic reprogramming in human and porcine vascular endothelium. Elife 2017;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Theodorou K, Boon RA. Endothelial cell metabolism in atherosclerosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2018;6:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng S, Bowden N, Fragiadaki M, Souilhol C, Hsiao S, Mahmoud M, Allen S, Pirri D, Ayllon BT, Akhtar S, Thompson AAR, Jo H, Weber C, Ridger V, Schober A, Evans PC. Mechanical activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α drives endothelial dysfunction at atheroprone sites. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:2087–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero CD, Varma TK, Hobbs JB, Reyes A, Driver B, Sherwood ER. The toll-like receptor 4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid a augments innate host resistance to systemic bacterial infection. 1 2011;79:3576–3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Putting endotoxin to work for us: Monophosphoryl lipid a as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell Mol Life Sci 2008;65:3231–3240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stark R, Choi H, Koch S, Lamb F, Sherwood E. Monophosphoryl lipid a inhibits the cytokine response of endothelial cells challenged with lps. Innate Immun 2015;21:565–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2:a006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalogeris TJ, Kevil CG, Laroux FS, Coe LL, Phifer TJ, Alexander JS. Differential monocyte adhesion and adhesion molecule expression in venous and arterial endothelial cells. Am J Physiol 1999;276:L9–l19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason JC, Yarwood H, Sugars K, Haskard DO. Human umbilical vein and dermal microvascular endothelial cells show heterogeneity in response to pkc activation. Am J Physiol 1997;273:C1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: Ii. Representative vascular beds. Circ Res 2007;100:174–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aboyans V, Lacroix P, Criqui MH. Large and small vessels atherosclerosis: Similarities and differences. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2007;50:112–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harrison DG, Marvar PJ, Titze JM. Vascular inflammatory cells in hypertension. Front Physiol 2012;3:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loperena R, Van Beusecum JP, Itani HA, Engel N, Laroumanie F, Xiao L, Elijovich F, Laffer CL, Gnecco JS, Noonan J, Maffia P, Jasiewicz-Honkisz B, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Mikolajczyk T, Sliwa T, Dikalov S, Weyand CM, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Hypertension and increased endothelial mechanical stretch promote monocyte differentiation and activation: Roles of stat3, interleukin 6 and hydrogen peroxide. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:1547–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao L, Harrison DG. Inflammation in hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2020;36:635–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wakefield TW, Myers DD, Henke PK. Mechanisms of venous thrombosis and resolution. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008;28:387–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saghazadeh A, Hafizi S, Rezaei N. Inflammation in venous thromboembolism: Cause or consequence? Int Immunopharmacol 2015;28:655–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao Q, Zhang P, Wang W, Ma H, Tong Y, Zhang J, Lu Z. The correlation analysis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-308g/a polymorphism and venous thromboembolism risk: A meta-analysis. Phlebology 2016;31:625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahemuti A, Abudureheman K, Aihemaiti X, Hu XM, Xia YN, Tang BP, Upur H. Association of interleukin-6 and c-reactive protein genetic polymorphisms levels with venous thromboembolism. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:3997–4002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matos MF, Lourenço DM, Orikaza CM, Bajerl JA, Noguti MA, Morelli VM. The role of il-6, il-8 and mcp-1 and their promoter polymorphisms il-6 −174gc, il-8 −251at and mcp-1 −2518ag in the risk of venous thromboembolism: A case-control study. Thromb Res 2011;128:216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, Santulli G. Hypertension, thrombosis, kidney failure, and diabetes: Is covid-19 an endothelial disease? A comprehensive evaluation of clinical and basic evidence. J Clin Med 2020;9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Turco S, Vianello A, Ragusa R, Caselli C, Basta G. Covid-19 and cardiovascular consequences: Is the endothelial dysfunction the hardest challenge? Thromb Res 2020;196:143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arts RJ, Carvalho A, La Rocca C, Palma C, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, Kleinnijenhuis J, Lachmandas E, Gonçalves LG, Belinha A. Immunometabolic pathways in bcg-induced trained immunity. Cell reports 2016;17:2562–2571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Chmielewski K, Stewart KM, Ashall J, Everts B, Pearce EJ, Driggers EM, Artyomov MN. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 2015;42:419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Donnelly RP, Finlay DK. Glucose, glycolysis and lymphocyte responses. Mol Immunol 2015;68:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol 1927;8:519–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature 2009;457:557–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F, Joosten LA, Ifrim DC, Saeed S, Jacobs C, van Loenhout J, de Jong D, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JW, van Crevel R, Netea MG. Bacille calmette-guerin induces nod2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:17537–17542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Manjeri GR, Li Y, Ifrim DC, Arts RJ, van der Veer BM, Deen PM, Logie C, O’Neill LA, Willems P, van de Veerdonk FL, van der Meer JW, Ng A, Joosten LA, Wijmenga C, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, Netea MG. Mtor- and hif-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 2014;345:1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F, Cheng SC, Ratter J, Berentsen K, van der Ent MA, Sharifi N, Janssen-Megens EM, Ter Huurne M, Mandoli A, van Schaik T, Ng A, Burden F, Downes K, Frontini M, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ouwehand WH, van der Meer JW, Joosten LA, Wijmenga C, Martens JH, Xavier RJ, Logie C, Netea MG, Stunnenberg HG. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science 2014;345:1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christ A, Gunther P, Lauterbach MAR, Duewell P, Biswas D, Pelka K, Scholz CJ, Oosting M, Haendler K, Bassler K, Klee K, Schulte-Schrepping J, Ulas T, Moorlag S, Kumar V, Park MH, Joosten LAB, Groh LA, Riksen NP, Espevik T, Schlitzer A, Li Y, Fitzgerald ML, Netea MG, Schultze JL, Latz E. Western diet triggers nlrp3-dependent innate immune reprogramming. Cell 2018;172:162–175 e114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sohrabi Y, Godfrey R, Findeisen HM. Altered cellular metabolism drives trained immunity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018;29:602–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van der Valk FM, Bekkering S, Kroon J, Yeang C, Van den Bossche J, van Buul JD, Ravandi A, Nederveen AJ, Verberne HJ, Scipione C, Nieuwdorp M, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Koschinsky ML, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Riksen NP, Stroes ES. Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation 2016;134:611–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sohrabi Y, Lagache SMM, Schnack L, Godfrey R, Kahles F, Bruemmer D, Waltenberger J, Findeisen HM. Mtor-dependent oxidative stress regulates oxldl-induced trained innate immunity in human monocytes. Front Immunol 2018;9:3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keating ST, Groh L, van der Heijden C, Rodriguez H, Dos Santos JC, Fanucchi S, Okabe J, Kaipananickal H, van Puffelen JH, Helder L, Noz MP, Matzaraki V, Li Y, de Bree LCJ, Koeken V, Moorlag S, Mourits VP, Domínguez-Andrés J, Oosting M, Bulthuis EP, Koopman WJH, Mhlanga M, El-Osta A, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP. The set7 lysine methyltransferase regulates plasticity in oxidative phosphorylation necessary for trained immunity induced by β-glucan. Cell Rep 2020;31:107548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keating ST, Groh L, Thiem K, Bekkering S, Li Y, Matzaraki V, van der Heijden C, van Puffelen JH, Lachmandas E, Jansen T, Oosting M, de Bree LCJ, Koeken V, Moorlag S, Mourits VP, van Diepen J, Stienstra R, Novakovic B, Stunnenberg HG, van Crevel R, Joosten LAB, Netea MG, Riksen NP. Correction to: Rewiring of glucose metabolism defines trained immunity induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Mol Med (Berl) 2020;98:1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Iacobazzi V, Infantino V. Citrate--new functions for an old metabolite. Biol Chem 2014;395:387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DeBerardinis RJ, Cheng T. Q’s next: The diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene 2010;29:313–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bisaccia F, De Palma A, Palmieri F. Identification and purification of the tricarboxylate carrier from rat liver mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1989;977:171–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gut P, Verdin E. The nexus of chromatin regulation and intermediary metabolism. Nature 2013;502:489–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Atp-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science 2009;324:1076–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Infantino V, Iacobazzi V, Palmieri F, Menga A. Atp-citrate lyase is essential for macrophage inflammatory response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013;440:105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, Carvalho A, Bekkering S, Lachmandas E, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, Cheng SC, Wang SY, Habibi E, Gonçalves LG, Mesquita I, Cunha C, van Laarhoven A, van de Veerdonk FL, Williams DL, van der Meer JW, Logie C, O’Neill LA, Dinarello CA, Riksen NP, van Crevel R, Clish C, Notebaart RA, Joosten LA, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, Netea MG. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab 2016;24:807–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ, Kelly B, Foley NH, Zheng L, Gardet A, Tong Z, Jany SS, Corr SC, Haneklaus M, Caffrey BE, Pierce K, Walmsley S, Beasley FC, Cummins E, Nizet V, Whyte M, Taylor CT, Lin H, Masters SL, Gottlieb E, Kelly VP, Clish C, Auron PE, Xavier RJ, O’Neill LA. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces il-1β through hif-1α. Nature 2013;496:238–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Serra-Pérez A, Planas AM, Núñez-O’Mara A, Berra E, García-Villoria J, Ribes A, Santalucía T. Extended ischemia prevents hif1alpha degradation at reoxygenation by impairing prolyl-hydroxylation: Role of krebs cycle metabolites. J Biol Chem 2010;285:18217–18224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:104–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Pagler TA, Ranalletta M, Lamkanfi M, Han S, Ishibashi M, Li R, Wang N, Tall AR. Increased inflammatory gene expression in abc transporter-deficient macrophages: Free cholesterol accumulation, increased signaling via toll-like receptors, and neutrophil infiltration of atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation 2008;118:1837–1847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gruenbacher G, Thurnher M. Mevalonate metabolism in immuno-oncology. Front Immunol 2017;8:1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stienstra R, Netea-Maier RT, Riksen NP, Joosten LAB, Netea MG. Specific and complex reprogramming of cellular metabolism in myeloid cells during innate immune responses. Cell Metab 2017;26:142–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhong C, Yang X, Feng Y, Yu J. Trained immunity: An underlying driver of inflammatory atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology 2020;11:284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Netea MG, Latz E, Mills KH, O’neill LA. Innate immune memory: A paradigm shift in understanding host defense. Nature immunology 2015;16:675–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Netea MG, Joosten LA, Latz E, Mills KH, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, O’Neill LA, Xavier RJ. Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 2016;352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.van der Heijden CD, Noz MP, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Riksen NP, Keating ST. Epigenetics and trained immunity. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018;29:1023–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arts RJ, Moorlag SJ, Novakovic B, Li Y, Wang S-Y, Oosting M, Kumar V, Xavier RJ, Wijmenga C, Joosten LA. Bcg vaccination protects against experimental viral infection in humans through the induction of cytokines associated with trained immunity. Cell host & microbe 2018;23:89–100. e105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JH, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ifrim DC, Logie C, Jacobs L, Jansen T, Kullberg B-J, Wijmenga C. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell host & microbe 2012;12:223–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fanucchi S, Fok ET, Dalla E, Shibayama Y, Börner K, Chang EY, Stoychev S, Imakaev M, Grimm D, Wang KC. Immune genes are primed for robust transcription by proximal long noncoding rnas located in nuclear compartments. Nature genetics 2019;51:138–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ifrim DC, Quintin J, Joosten LA, Jacobs C, Jansen T, Jacobs L, Gow NA, Williams DL, van der Meer JW, Netea MG. Trained immunity or tolerance: Opposing functional programs induced in human monocytes after engagement of various pattern recognition receptors. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2014;21:534–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van der Heijden CD, Keating ST, Groh L, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Riksen NP. Aldosterone induces trained immunity: The role of fatty acid synthesis. Cardiovascular Research 2020;116:317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.de Laval B, Maurizio J, Kandalla PK, Brisou G, Simonnet L, Huber C, Gimenez G, Matcovitch-Natan O, Reinhardt S, David E. C/ebpβ-dependent epigenetic memory induces trained immunity in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell stem cell 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ostuni R, Piccolo V, Barozzi I, Polletti S, Termanini A, Bonifacio S, Curina A, Prosperini E, Ghisletti S, Natoli G. Latent enhancers activated by stimulation in differentiated cells. Cell 2013;152:157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yoshida K, Maekawa T, Zhu Y, Renard-Guillet C, Chatton B, Inoue K, Uchiyama T, Ishibashi K-i, Yamada T, Ohno N. The transcription factor atf7 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced epigenetic changes in macrophages involved in innate immunological memory. Nature immunology 2015;16:1034–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schlums H, Cichocki F, Tesi B, Theorell J, Beziat V, Holmes TD, Han H, Chiang SC, Foley B, Mattsson K. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of nk cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity 2015;42:443–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sun Y, Lu Yifan, Saredy Jason, Wang Xianwei, Drummer Charles IV, Shao Ying, Saaoud Fatma, Xu Keman, Liu Ming, Yang William Y., Jiang Xiaohua, Wang Hong, Yang Xiaofeng. Ros systems are a new integrated network for sensing homeostasis and alarming stresses in organelle metabolic processes. REDOX BIOLOGY 2020;17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Saaoud F, Drummer IVC, Shao Y, Sun Y, Lu Y, Xu K, Ni D, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Circular rnas are a novel type of non-coding rnas in ros regulation, cardiovascular metabolic inflammations and cancers. Pharmacol Ther 2020:107715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sun L, Wang X, Saredy J, Yuan Z, Yang X, Wang H. Innate-adaptive immunity interplay and redox regulation in immune response. Redox Biol 2020;37:101759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fu H, Sun Y, Shao Y, Saredy J, Cueto R, Liu L, Drummer Ct, Johnson C, Xu K, Lu Y, Li X, Meng S, Xue ER, Tan J, Jhala NC, Yu D, Zhou Y, Bayless KJ, Yu J, Rogers TJ, Hu W, Snyder NW, Sun J, Qin X, Jiang X, Wang H, Yang X. Interleukin 35 delays hindlimb ischemia-induced angiogenesis through regulating ros-extracellular matrix but spares later regenerative angiogenesis. Front Immunol 2020;11:595813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jeljeli M, Riccio LGC, Doridot L, Chêne C, Nicco C, Chouzenoux S, Deletang Q, Allanore Y, Kavian N, Batteux F. Trained immunity modulates inflammation-induced fibrosis. Nature communications 2019;10:1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]