Abstract

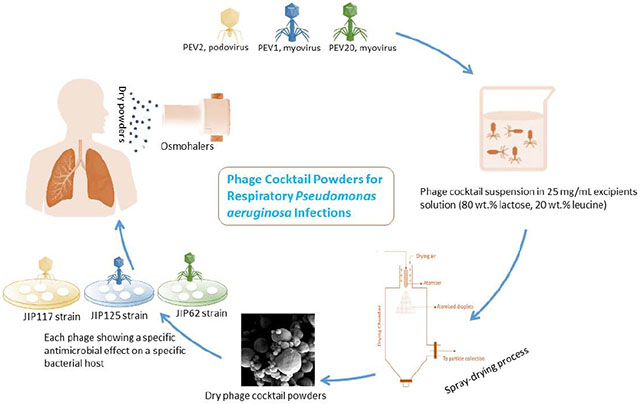

Phage cocktail broadens the host range compared with a single phage and minimizes the development of phage-resistant bacteria thereby promoting the long-term usefulness of inhaled phage therapy. In this study, we produced a phage cocktail powder by spray drying three Pseudomonas phages PEV2 (podovirus), PEV1 and PEV20 (both myovirus) with lactose (80 wt.%) and leucine (20 wt. %) as excipients. Our results showed that the phages remained viable in the spray dried powder, with little to mild titer reduction (ranging from 0.11 to 1.3 logs) against each of their specific bacterial strains. The powder contained spherical particles with a small volume median diameter of 1.9 μm (span 1.5), a moisture content of 3.5 ± 0.2 wt. %., and was largely amorphous with some crystalline peaks, which were assigned to the excipient leucine, as shown in the X-ray diffraction pattern. When the powder was dispersed using the low- and high-resistance Osmohalers, the fine particle fraction (FPF, wt. % of particles <5 μm in the aerosols relative to the loaded dose) values were 45.37 ± 0.27% and 62.69 ± 2.1% at the flow rate of 100 and 60 L/min, respectively. In conclusion, the PEV phage cocktail powder produced was stable, inhalable and efficacious in vitro against various MDR P. aeruginosa strains that cause pulmonary infections. This formulation will broaden the bactericidal spectrum and reduce the emergence of resistance in bacteria compared with single-phage formulations reported previously.

Keywords: Phage therapy, Phage combination, Lung infection, Pulmonary infections, Inhalation drug delivery, Powder aerosol, Inhalation aerosol

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Inhaled phage therapy is emerging as a promising alternative to antibiotics for treatment of respiratory infections caused by multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria. The efficacy and safety of inhaled phage therapy have been demonstrated in animal models (Chang et al., 2018; Golshahi et al., 2008; Semler et al., 2014) and humans (Garsevanishvili, 1974). Unlike antibiotics, phages have relatively narrow host range and cause less damage to the natural microflora (Park and Nakai, 2003; Pereira et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2011). However, due to narrow host spectrum, a single phage is only effective against a selection of bacterial isolates within the same species (Hyman and Abedon, 2010) and bacteria can develop resistance to phages over time (Cairns et al., 2009; Labrie et al., 2010). To overcome the issue of phage-resistance and narrow host range profile, the use of phage cocktail over a single phage is often encouraged for phage therapy.

Phages with different host spectrum can be mixed as cocktails to broaden the antibacterial spectrum activity (Chang et al., 2017). Development and preparation of a personalized phage treatment may take weeks, which is an unviable option for critically ill patients such as those in intensive care unit with respiratory tract infections. Hence, development of phage cocktails with a wide host range is highly advantageous, particularly when it is difficult to provide timely personalized phage therapy. Furthermore, the use of phage cocktails can potentially constrain the emergence of phage-resistant bacterial mutants (Gu et al., 2012). Studies have repeatedly shown that the emergence of resistance to phage cocktail is less common than resistance to the individual phage suspension (Costa et al., 2019; Duarte et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2016). Due to these advantages, phage cocktails have been utilized to treat patients with respiratory infections (Dedrick et al., 2019; Kutateladze and Adamia, 2008). In these clinical case studies, phages were formulated in liquid suspension and delivered using commercial nebulizers. However, the stability of phages in liquid formulation is phage-dependent and loss of bioactivity is often observed during long-term storage (Ackermann et al., 2004). In addition, different types of phage when mixed in a cocktail can interact adversely, causing unpredictable loss in titre and efficacy as happened in the PhagoBurn clinical trial (Jault et al., 2019). But the influence of phage-phage interaction in solid state is unknown. Powder formulation of phages provides advantages over liquid formulations, including long shelf-life, easy storage, and transport (Chang et al., 2017; Dini and De Urraza, 2013; Merabishvili et al., 2013).

Spray drying process has been used to produce inhalable dry powder formulations of phages and phage cocktails (Chang et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019; Matinkhoo et al., 2011). Sugars such as lactose and trehalose are often used to protect the phages from heat, drying and shear stresses during the process (Chang et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019; Leung et al., 2016). In addition, hydrophobic amino acid L-leucine is widely utilized to improve the powder flowability and dispersibility, as well as to protect the phage powders from moisture-induced degradation and subsequent inactivation of phages (Chang et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2019; Leung et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2019; Matinkhoo et al., 2011). Although powder formulations containing a single phage have been explored extensively, production of phage cocktail powder formulations is scarce with only one study reported by Finlay and colleagues who used cocktails containing two and three myovirus phages (Matinkhoo et al., 2011). Currently, one cannot predict that a method/composition for spray drying a single phage class/family will be applicable to a mixture of different phages. To date, the feasibility of producing powder formulations of a mix of phages (podovirus and myovirus) with different morphology in the cocktail formulation is unknown.

This study aimed to produce a stable and inhalable dry powder formulation of a phage cocktail comprised of two long-tailed myoviruses (PEV1 and PEV20) and a short-tailed podovirus (PEV2). These three phages are infective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, known to be prevalent in patients with progressive lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Wu et al., 2015). To our knowledge, this is the first study on inhaled phage cocktail powder formulation containing two different phage families.

Materials and methods

Bacteria and phages

Pseudomonas phages PEV2 (podovirus), PEV1 and PEV20 (both myovirus) were isolated by the Kutter Lab (Evergreen State College, WA, USA). Each of the three phages were amplified and purified separately using the Phage-on-Tap protocol (Bonilla et al., 2016) with minor modifications. Briefly, 200 mL of nutrient broth (NB, Amyl Media, Australia) was mixed with 0.1 volumes of bacterial host (P. aeruginosa PAV237 at stationary phase). The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37 ° C at 220 rpm. Then, a volume (200 μL) of phage lysate at 109 PFU/ml) was added to the mixture, followed by further incubation overnight. Next day, the mixture was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min and the supernatant was sterilized using 0.22 μm polyethersulfone membrane filter. The phage lysate was further purified using ultrafiltration (100 kDa Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter, Sigma, Australia) and the media was replaced with salt-magnesium buffer (SMB, 5.2 g/L of sodium chloride, 2 g/L of magnesium sulfate, 6.35 g/L of Tris-HCL and 1.18 g/L of Tris-base) with pH adjusted by 2.5 mM NaOH to 7.4.

Spray drying

Lactose monohydrate (DFE Pharma, Goch, Germany) and L-leucine (Sigma-Aldrich, NSW, Australia) were co-spray dried with a cocktail of phages comprising PEV1, PEV2 and PEV20. The excipient composition used in this study was 80% (wt/wt) lactose and 20% (wt/wt) leucine as our group has previously demonstrated individual phage stability and powder dispersibility with long shelf-life with this formulation (Chang et al., 2019). The liquid feed consisted of 100 mL of excipient solution (25 mg/mL) in ultra-pure water and 1 mL of phage cocktail suspension (of the three phages at ratio of 1:1:1, each with a titre of 109 PFU/mL) with pH adjusted to 7.4. The phage-excipient suspension was tested for phage viability. A Büchi 290 spray dryer coupled with a conventional two-fluid nozzle as an atomizer was used. The solution was loaded at a constant feed rate of 1.8 mL/min, atomizing air flow rate of 742 L/hr, an aspiration rate of 35 m3/h and inlet temperature of 60°C. The samples passing through the cyclone were collected in a glass vial. A small amount of powders was dissolved in PBS with a final concentration of 25 mg/mL. Plaque assay was performed to test the phage viability after spray drying process. An aliquot of powder was stored at 20°C/15% RH to assess storage stability.

Plaque assay

The viability of phages was determined using a standard plaque assay as described before (Chang et al., 2017). Briefly, NB agar plates were overlaid with soft agar containing 200 μL of overnight culture of P. aeruginosa strains JIP62, JIP117, and JIP125 (provided by the Iredell group at Westmead Hospital) for enumeration of PEV20, PEV2 and PEV1, respectively. For each phage, 10 μL of serially diluted samples were dropped on top of the corresponding soft agar, air-dried and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h prior to quantification.

Particle morphology

The particle morphology of phage cocktail powder was measured by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Ultra Plus HD, Oberkochen, Germany). The samples were prepared on a carbon tape and then sputter coated with 15 nm of gold using a K550X sputter coater (Quorum Emitech, Kent, UK) before imaging.

Particle size distribution

The particle size distribution was measured on a Malvern Mastersizer 2000 (Malvern Instruments, UK). The powder was loaded onto Scirocco 2000 dry powder module (Malvern Instruments, UK) and then dispersed using compressed air at 4.0 bar. The results were reported as volumetric diameters at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles (D10, D50, and D90) and span (defined as (D90-D10)/D50). All measurements were conducted in triplicate.

Powder crystallinity

The powder crystallinity was examined by X-ray diffraction (Model D5000; Siemens, Munich, Germany) under ambient conditions. The powder was exposed to Cu Ka radiation at 30 mA and 40 kV, and the relative intensity was measured with an angular increment rate of 0.04° 2θ/s from 5° to 60°.

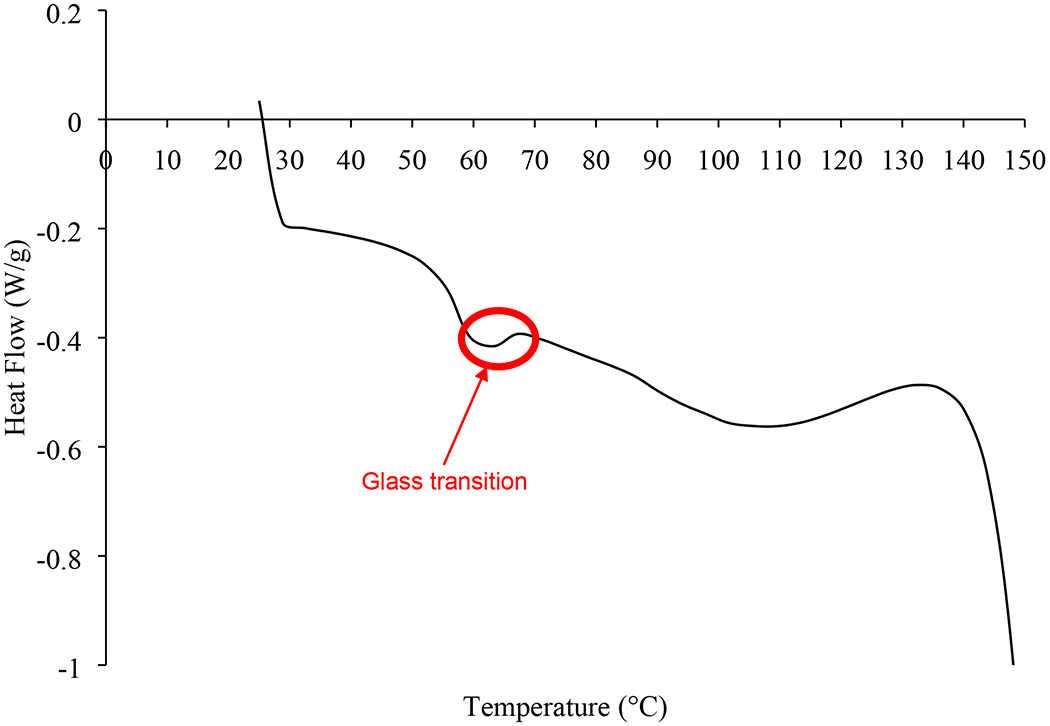

Thermal analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) instruments (Mettler Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) were used to measure the thermal properties of the phage cocktail powder. For DSC analysis, each sample (3 ± 1 mg) was weighed into an aluminum crucible, crimped-sealed to a perforated lid on top, and then heated from 30 to 150°C at a rate of 10°C/min with nitrogen purge (250 cm3/min). For TGA analysis, the sample (3 ± 1 mg) was weighed into a crucible and heated from 30 to 150°C at a rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen flow. STARe software (Mettler Toledo) was used for data analysis. Tg was analyzed by fitting straight lines to the DSC curve and then taking an average of the onset and midpoint temperatures for the transition. The measurement was repeated twice.

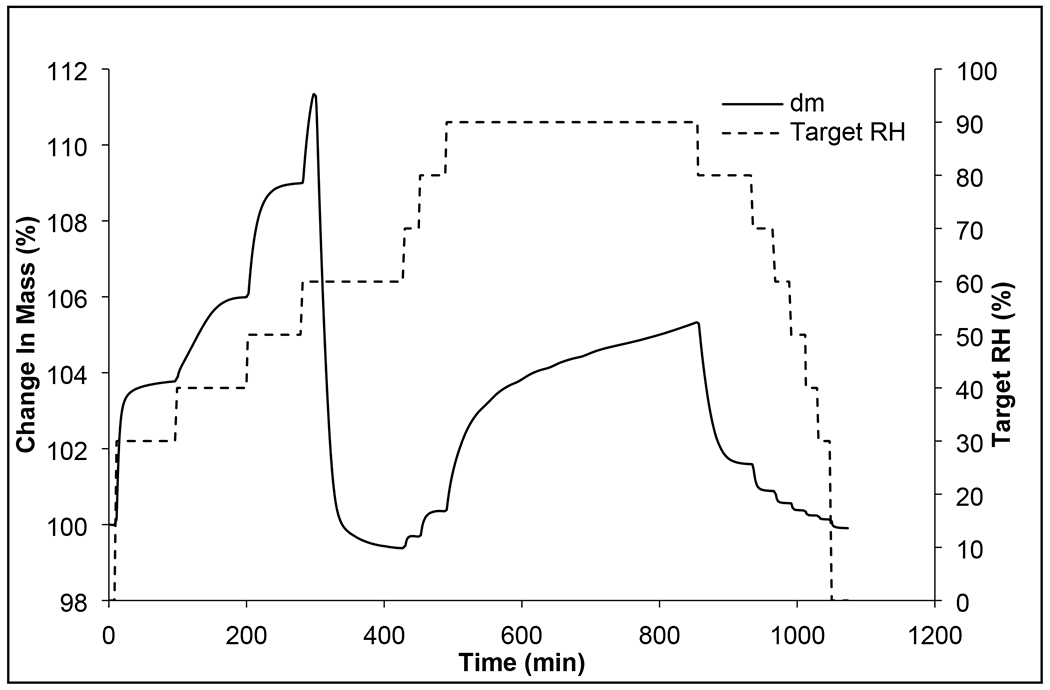

Moisture sorption

The moisture sorption profile of the phage powder was measured by a dynamic vapour sorption (DVS) instrument (DVS-Instrinsic, Surface Measurement Systems, London, UK). The powder (~ 5 mg) was exposed to a moisture ramping cycle of 0 to 90% relative humidity (RH) at a step increase of 10%. The criterion for equilibrium moisture content at each RH was defined as less than 0.02 %wt. change per minute.

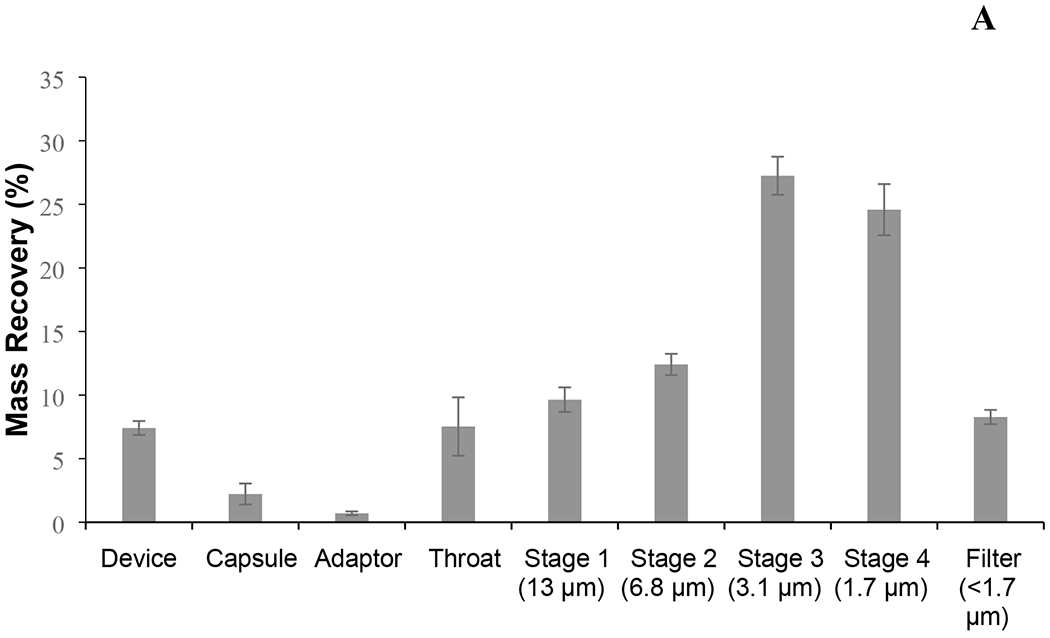

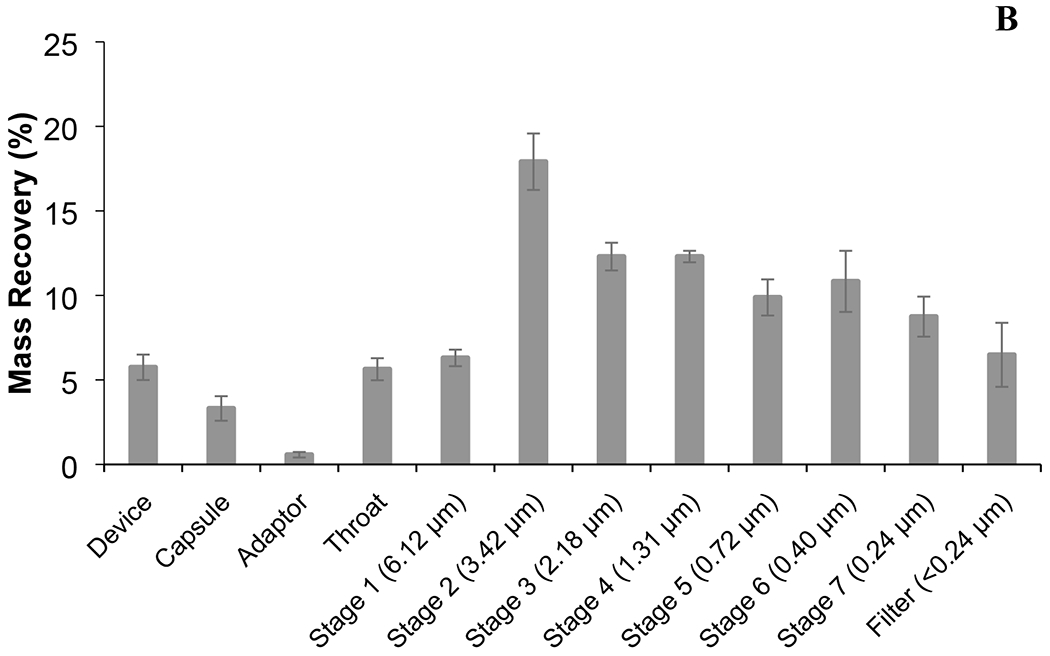

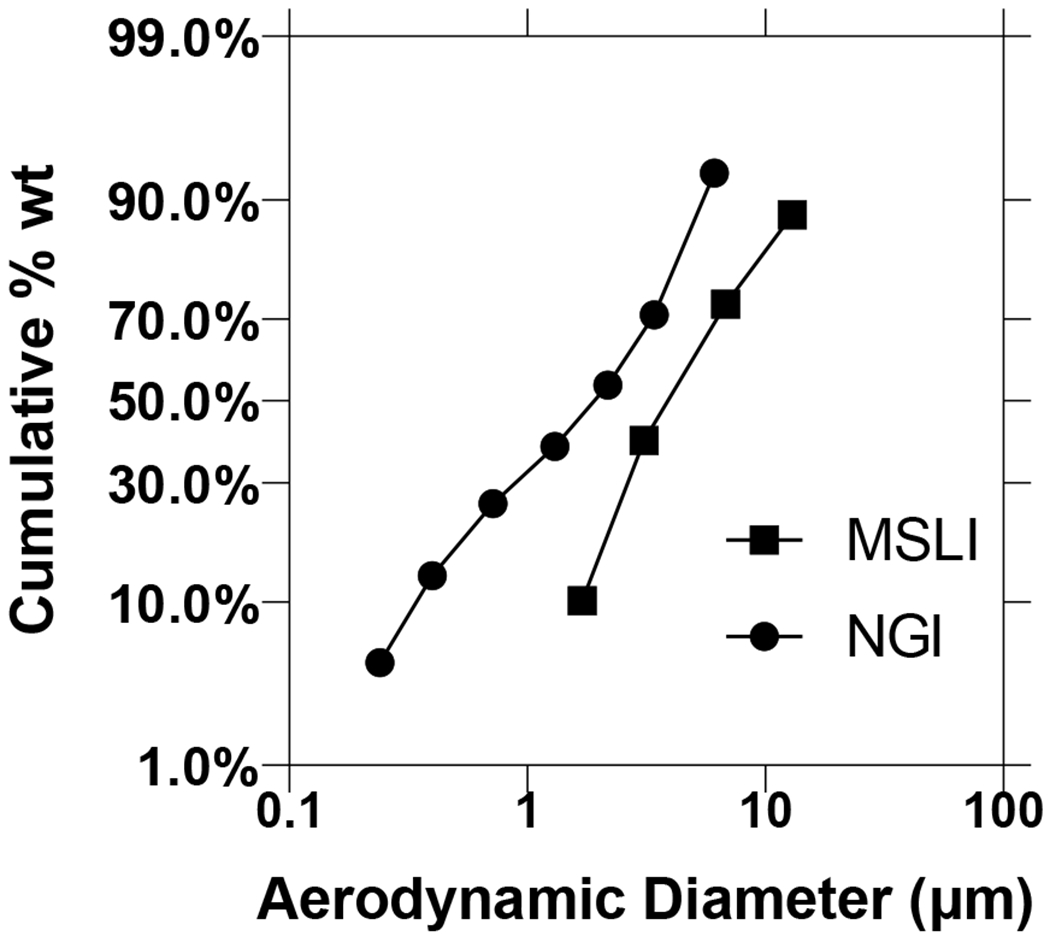

Powder dispersion

The aerosol performance of phage cocktail powder was performed using a Next Generation impactor (NGI) and a multi-stage liquid impinger (MSLI) coupled to a mouthpiece adapter and a USP throat. A powder sample (25 ± 5 mg) was loaded in a size 3 HPMC capsule and dispersed through an Osmohaler™. For NGI, the powder was dispersed through a low-resistance inhaler at 100 L/min for 2.4s and the cut-off diameters of stages 1–8 were 6.12, 3.42, 2.18, 1.31, 0.72, 0.40, 0.24 and < 0.24 μm, respectively. For MSLI, the powder was dispersed through a high-resistance inhaler at 60 L/min for 4s and the cut-off diameters of the stages 1-4 and the filter were 13, 6.8, 3.1, 1.7 and <1.7 μm, respectively. Ultra-pure water was used to dissolve the powder and then analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The fine particle fraction (FPF) was determined as the mass fraction of particles ≤ 5.0 μm with respect to the loaded dose. The FPF was obtained by interpolation from the plot of the cumulative fraction versus the cut-off diameter of NGI stages, according to the British Pharmacopeia 2005 (Jain, 2008).

High-performance liquid chromatography

HPLC based chemical assay was used over biological assay to avoid titration error of plaque assay (Anderson et al., 2011) that can quickly intensify when different compartments are individually enumerated (Leung et al., 2016). The deposition of lactose in capsule, inhaler, adaptor, throat and each stage of NGI and MSLI was analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Model LC-20; Shimadzu, Japan) with RI detection. A SIL-20A HT auto-sampler, CBM-20A controller, LC-20AT pump, RID-10A RI detector, Agilent Hi-Plex Ca2+ Ligand Exchange Columns (300 × 7.7 mm, 8 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), and LC Solution software were used. The chromatographic conditions used were an oven temperature of 85°C, an injection volume of 50 μL and a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min, and ultra-pure water was used as a mobile phase.

Results and discussion

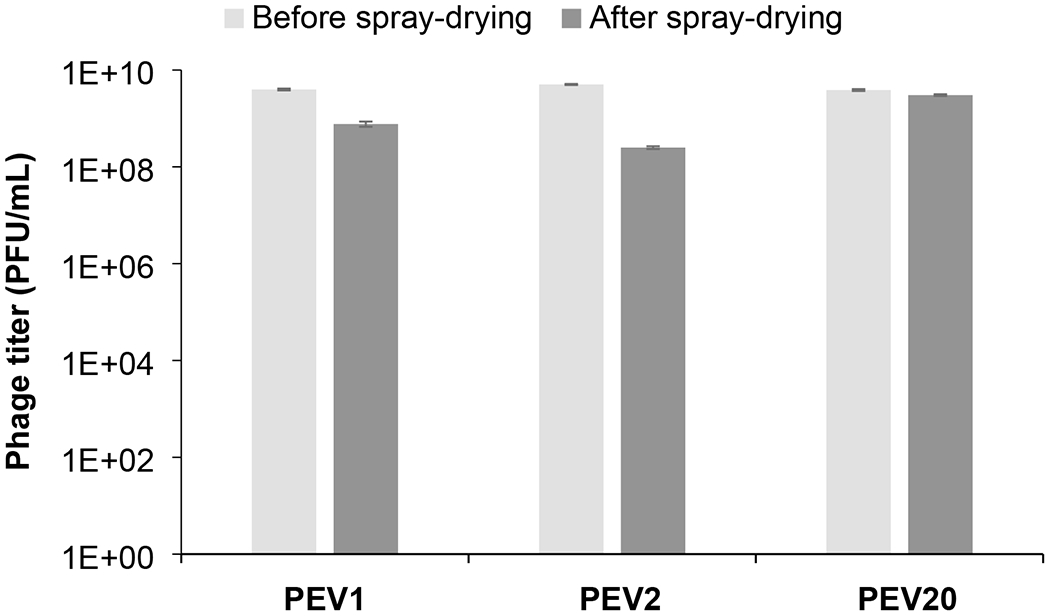

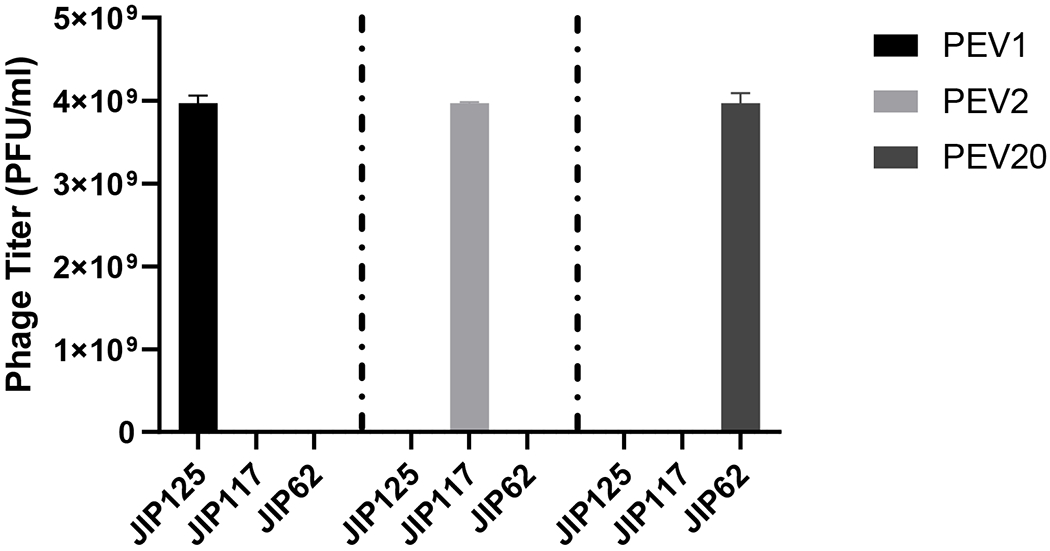

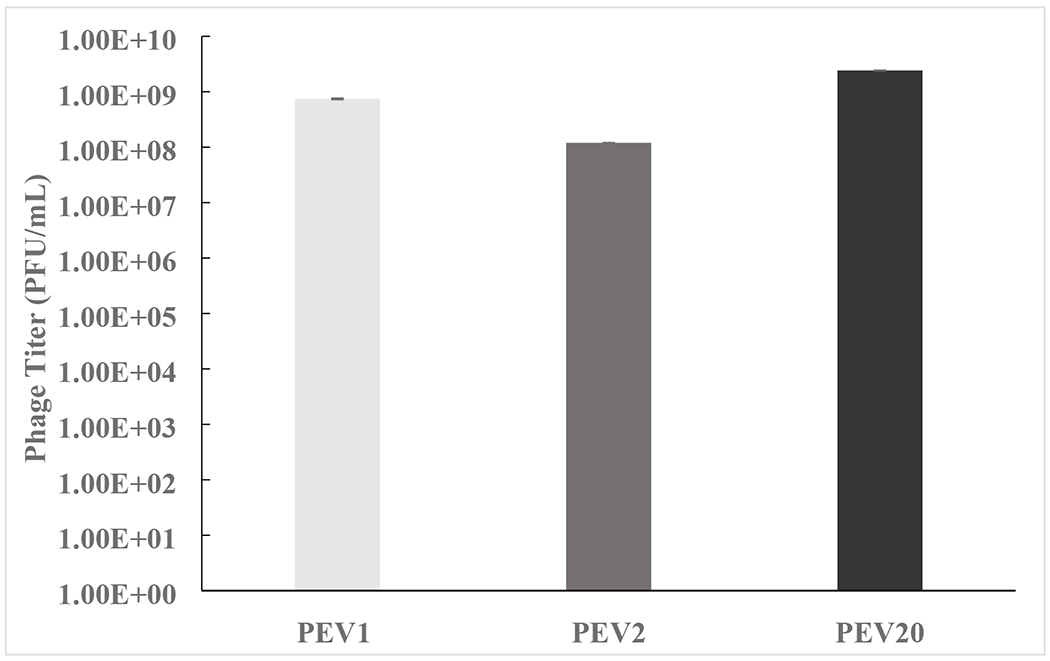

Our results showed that all three types of phages remained viable in the spray dried powder, with little to mild titer reduction against their specific bacterial strains (Figure 1). A major issue for producing the cocktail powder during spray drying was maintaining the biological viability of phages in the process. Phages are exposed to shear, thermal and dehydration stresses during spray drying can cause phage inactivation. Phage inactivation can occur when they are exposed to shear stress during atomization of the liquid feed into smaller droplets (Leung et al., 2016). These droplets are dried by hot air, often at 60°C or above, to produce dry powders. Although exposure to air at >60°C may be high for some phages (i.e. thermal stress) (Pope et al., 2004), evaporative cooling in the drying droplets may lower the temperature sufficiently for phage viability (Snyder and Lechuga-Ballesteros, 2008). Phages are also exposed to dehydration stress in the dry particles, which can be alleviated by incorporating sugars such as lactose, trehalose and sucrose into the formulation (Cox et al., 1974). These amorphous sugars serve as water-replacing agents, or they form a glass matrix to minimize molecular mobility (Chang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019), thereby stabilizing the phages in solid state (Maa et al., 1998). Phages are exposed to shear stress when the liquid suspension is fed through the tubing and the nozzle, followed by mechanical stress during atomization of the liquid feed into smaller droplets. Large air-liquid interfacial area is generated during this process and this can cause phage inactivation (Trouwborst et al., 1972; Trouwborst et al., 1974). Phages which experience three phase boundaries from gas phase to liquid phase to solid phase via convection and diffusion are prone to subsequent inactivation as these phases forced to deform phages (Adams et al., 1948; Margaret et al., 1942; Thompson et al., 1998). All of these stresses can potentially compromise the phage viability and result in loss of their biological activity (i.e. bactericidal effect).

Figure 1.

Titer of PEV1, PEV2 and PE20 in phage cocktail formulation before and after spray drying at 20C/15%RH.

In this study, the three Pseudomonas phages PEV1, PEV2 and PEV20 exhibited titer losses of 0.1, 1.3 and 0.7 log10 after spray drying (Figure 1). Our previous studies on single-phage formulations showed similar titer reductions (<0.8 log10) when myovirus PEV1 and PEV20 were individually spray dried with lactose and leucine (Chang et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2018). In the presence of sugars (trehalose and mannitol) and leucine, podovirus PEV2 exhibited 0.8 log10 titer loss upon atomization and a further 0.8 log10 loss during the drying process (Leung et al., 2016). The viability of phages PEV1, PEV2 and PEV20 in the cocktail after spray drying was no different to that of individual phages. Hence, it is encouraging to confirm the same stabilizing strategy used for single-phage formulations is application to the cocktail formulation. The presence of different phages in the cocktail did not influece the viability of individual phages.

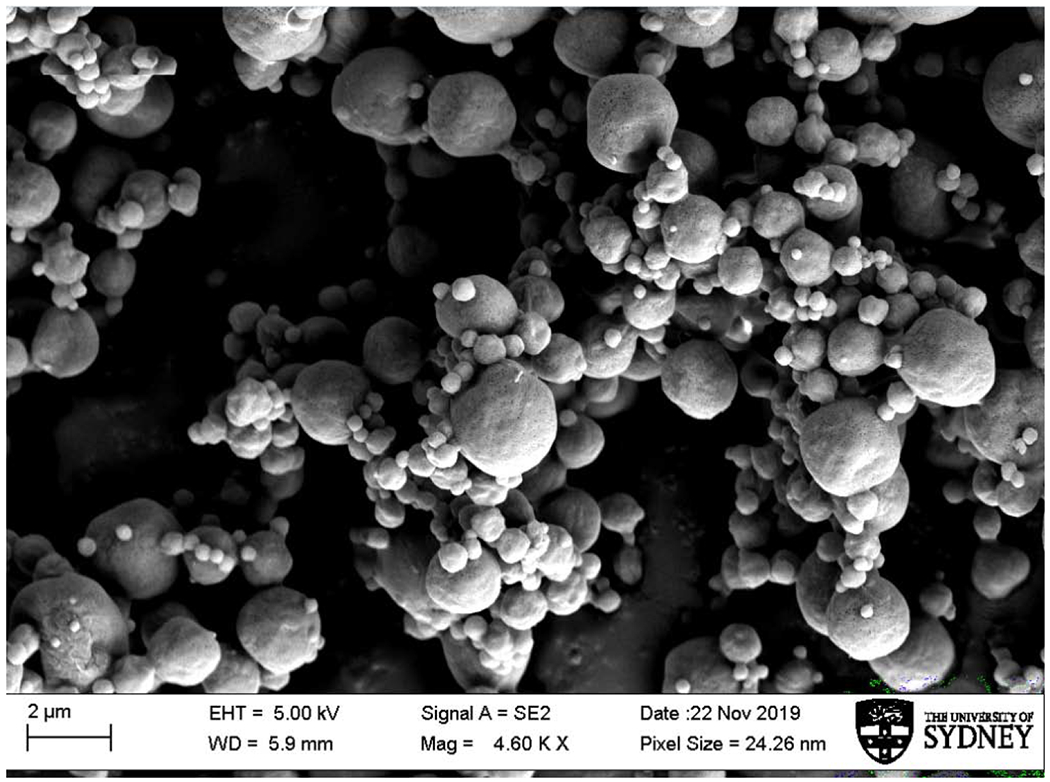

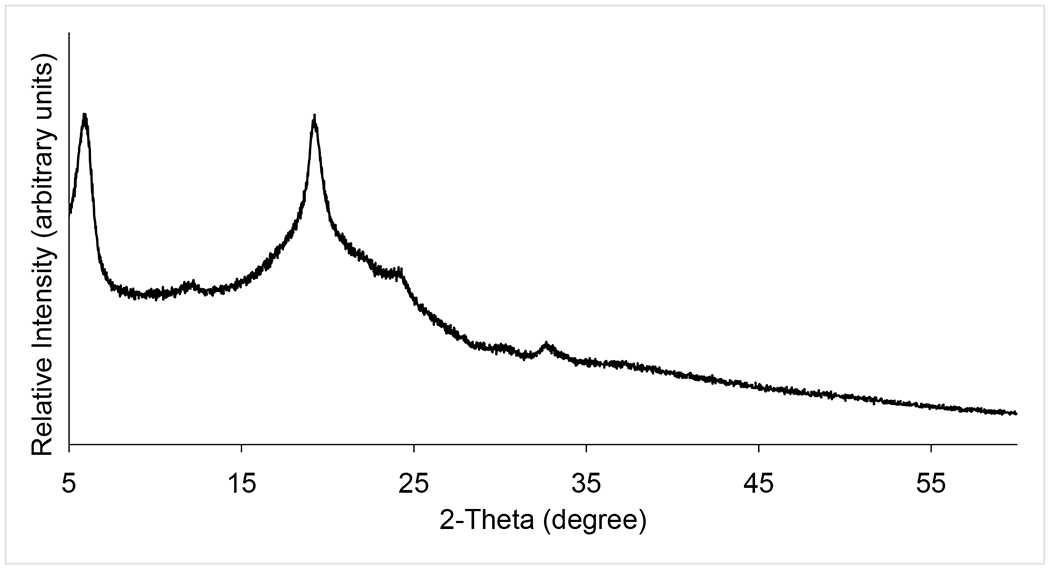

In our previous study, phages remained stable with negligible titer loss in the spray dried formulation of phages over the tested period of one year at 15% RH with subsequent storage (Chang et al., 2019). The spray dried phage cocktail formulation is promising as it provides not only the stability of individual phages in solid state, but also the potential to eliminate the need for cold chain supply. This study also aligns with our previous work on single-phage formulations that phages remain biologically stable in powders containing lactose and leucine when stored at an ambient termperate provided the surrounding RH is low (Chang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019). The spray dried phage cockail powder produced in this study had spherical particles with slightly corrugated surfaces due to presence of leucine (Figure 2). In this study, we used phages from two different families – podovirus (PEV2) and myovirus (PEV1 and PEV20). Podovirus phages have short, non-contractile tails, and have no baseplate (Nobrega et al., 2018). In contrary, myovirus phages have long, contractile tails with a baseplate complex (Nobrega et al., 2018). Such structural differences may have caused different titer losses after spray drying with more pronounced titer drop observed for podovirus PEV2. However, morphological differences cannot fully explain different in phage viability as those with longer tail are known to be more vulnerable to shear and mechanical stresses (Leung et a., 2019). Hence, other factors such as temperature sensitivity and vulnerability at air-liquid-interface may have caused varying titer losses, suggesting that each phage require formulation optimization. In addition, phages may interact with other phages in liquid (during spray drying) or solid (after spray drying) state. For example, significant drop in global titer (up to 5 log) was observed in the Phagoburn study when ten phages were formulated as a cocktail. However, the influence of phage-phage interaction in solid state is yet to be elucidated.The particle size distribution was within the inhalable diameter range with D50 of 1.94 ± 0.03 μm (span 1.5 ± 0.05) and the powder had a moisture content of 3.5 ± 0.2 wt. %. The XRD data (Figure 3) showed that the phage cocktail formulation was partially crystalline and had diffraction peaks at around 6°, 19°, 24°, and 33°, which are ascribable to L-leucine (Lin et al., 2019). Leucine forms crystalline structures on the particle surface and provides protection from moisture-induced powder degradation (Najafabadi et al., 2004). The phage cocktail powder showed a water sorption profile with the characteristic of recrytstallization of amorphous powders (Figure 4). The mass of the powder increased gradually due to moisture uptake, followed by a decrease within 20 min at 60% RH as water was expelled from the crystal lattice. The observed mass drop is due to recrystallization of amorphous lactose causing expulsion of water from the crystal lattice. Phage stability in solid state is heavily dependent on the presence of amorphous sugars that form glassy matrix (Chang et al., 2020). When this amorphous sugar matrix is lost due to recrystallization, phages become destabilized and lose their bioactivity (Chang et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2019). Hence, the phage cocktail powder containing 80% lactose and 20% leucine should be stored and handled well below 60% RH to prevent crystallization. Moreover, the powder may incline to recrystallize if the temperature gap between the storage and glass transition (Tg) is less than about 50°C (Chang et al., 2020). As the phage cocktail powder showed a Tg of 57°C (Figure 5), the recommended storage temerpature is below 20°C. We have previously shown that phage powders with >70% lactose can remain biologically and physico-chemically stable during storage at 20°C/15% RH for 12 months (Chang et al., 2019). However, further study is needed to assess whether all three phages can remain viable during extended storage stability test.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image of spray-dried phage cocktail powders.

Figure 3.

X-ray powder diffraction pattern of spray-dried phage cocktail powder.

Figure 4.

Moisture sorption kinetic profiles of phage cocktail formulation.

Figure 5.

DSC thermogram of spray-dried phage cocktail formulation.

The aerosol performance of the phage cocktail powder was assessed at two flowrates by the Osmohaler with different resistance to air flow (Figure 6). The in vitro deposition profiles show a majority of the aerosol deposited beyond the first stage of the impactors. There was very little (<5%) powder residue in the capsule, and the total capsule and device retention was also low (<10%) (Figure 6). This was probably due to the presence of leucine as a hydrophobic excipient as it is known to enhance flow and dispersibility, besides moisture protection (Li et al., 2017). The FPF values relative to the loaded dose were 45.4 ± 0.3% and 62.7 ± 2.1%, when the powder was dispersed at 60 and 100 L/min by the high-and low-resistance Osmohalers, respectively. The FPF value relative to the emitted dose was 51.8 ± 1.5% and MMAD emitted dose was 4.22 ± 0.55 μm, when the powder was dispersed at 60 L/min by the high-resistance Osmohaler. The FPF value relative to the emitted dose was 77.1 ± 0.5% and MMAD emitted dose was 2.31 ± 0.01 μm, when the powder was dispersed at 100 L/min by the low-resistance Osmohaler. Taken together, these data show that the powder was dispersible and suitable for inhalation delivery.

Figure 6.

The MSLI (A) and NGI (B) deposition profile of spray-dried phage cocktail formulation. The aerodynamic cut-off diameter (μm) of each stage is quoted in parentheses. Phage cocktail powders were dispersed in MSLI at 60 L/min for 4 s using a high-resistance Osmohaler™ and in NGI at 100 L/min for 2.4 s using a low-resistance Osmohaler™.

The plots of the aerosol size distribution data allows a clear comparison between the two inhalers at the two flow rates (Figure 7), showing the powder that the powder was better dispersed using the low-resistance inhaler at the higher flow of 100 L/min. For powder inhalers, a critial air flow is necessary to generate sufficient turbulence and powder-wall impaction for deagglomeration (Coates et al., 2005; deBoer et al., 2012; Tong et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2013). The low-resistance Osmohaler is very similar to the Aerolizer and Dinkihaler in design which were shown to require a critical flow of ≥60 L/min for maximizing the dispersion performance of powders, regardless whether they are crystalline (e.g. mannitol) or amorphous (e.g. disodium cromoglycate) (Chew and Chan, 1999, 2002a, b; Coates et al., 2006). Therefore, it is likely that in the present study the critical flow has already reached for the optimal dispersion performance of the phage powder formulation with the low-resistance Osmohaler. The high-resistant Osmohaler is the same as the low-resistant version except the air inlet is narrower which increases the resistance. The inlet size in the Aerolizer is known to control the generation of turbulence and particle impaction in the inhaler, as well as the rates of air flow development and powder emptying from the device (Coates et al., 2006). At low flow rates below 45 L/min, reducing the air inlet size increased the linear air velocity (which is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the air inlet) which improved the powder dispersion by increasing the turbulence levels and particle impaction velocities generated in the device. In contrast, the inhaler dispersion performance was reduced at higher flow rates of ≥60 L/min. This was attributed to the premature release of powder from the capsule and device prior to the full development of the turbulence and particle impaction velocities (Coates et al., 2006). It is very likely that in the present study the same situation occurs in the high-resistant Osmohaler which has a similar design to the Aerolizer with a reduced inlet size, resulting in the lower dispersibility and reduced FPF of the phage powder.

Figure 7.

Particle size distribution of spray-dried phage cocktail formulation for the MSLI and NGI. Phage cocktail powders were dispersed in MSLI at 60 L/min for 4 s using a high-resistance Osmohaler™ and in NGI at 100 L/min for 2.4 s using a low-resistance Osmohaler™.

In general, a high-resistance device with a low inspiratory air velocity is likely to reduce oropharyngeal deposition and result in an aerosol of a given particle size distribution travelling deeper into the lungs (Harris, 2015). Our previous study showed no significant difference in the lung deposition in healthy subjects between the low-and high-resistance Osmohalers (Tong et al., 2015). In that study, the aerosols had a FPF of −30% generated by inhalation at a relatively low flow rate of 50–70 L/min (Tong et al., 2015). It would be necessary in the future to find out the difference in the in vivo deposition of the aerosols with different FPF (45.4% vs 62.7%) and air flows (60 L/min vs 100 L/min) observed in the present study, as it will impact the efficacy of inhaled phage therapy. Although the in vitro throat depositions at both flowrates with the two inhalers were similar (<10 %), the data are not directly translatable to in vivo, due to the substantial difference in the geometries between the USP induction port and the human airways (Newman and Chan, 2020) including the fact that the latter is deformable during inhalation (Cheng et al., 2019).

The development of phage cocktails can overcome the limitation of a narrow host range and reduce the probability of phage-resistant bacterial mutants (Chan et al., 2013). Phages PEV1, PEV2 and PEV20 could selectively killed clinical isolates P. aeruginosa JIP125, JIP117 and JIP62, respectively (Figure 8). Hence, the developed phage cocktail powder could increase the chance of treating multiple P. aeruginosa strains infection. The dose uniformity of each phage in the powder was consistent (Figure 9), indicating that phages were distributed equally in the powder.To date, phage cocktail in dry powder formulation for inhalation administratoin to the lung has not been explored much yet. Compared to liquid formulation, dry powder formulation is encouraging as it has the potential for long-term storage and improved transport and administration (Ackermann et al., 2004; Chang et al., 2018). In our previous work on single-phage formulations, spray dried phage powders with the same excipeint composition showed very similar particle morphology, particle size, XRD patterns, moisture sorption profile, thermal properties and aerosol performance, regardless of the phage type used (Chang et al., 2017). Here, we found the phage cocktail formulation containing a mixture of podovirus and myovirus phages also showing similar physico-chemical powder properties as well as biological stability compared with those single-phage powders. This is signficant as the formulation development of phage cocktail powders could potentially be expedited by extrapolation from the formulation properties of individual phage.

Figure 8.

Titer of PEV1, PEV2 and PEV20 against three bacterial isolates P. aeruginosa JIP 62, JIP 117, and JIP 125.

Figure 9.

Dose uniformity (titer of PEV1, PEV2, PEV20 in aliquots (n=3 or more) of powders reconstituted in PBS).

Conclusion

A Pseudomonas phage cocktail comprising two myoviruses and a podovirus was prepared in a stable and inhalable dry powder formulation by spray drying. The formulation showed minimal titer reductions in the phages over a month of storage. The powder was dispersible using both low-and high-resistance Osmohalers. Long-term storage stability studies of the biological and physico-chemical properties are warranted for further phage product development.

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Project Grant APP1140617). H.-K. Chan is supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R33AI121627. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ackermann H-W, Tremblay D, Moineau S, 2004. Long-term bacteriophage preservation, World Federation for Culture Collections Newsletter. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Rashid MH, Carter C, Pasternack G, Rajanna C, Revazishvili T, Dean T, Senecal A, Sulakvelidze A, 2011. Enumeration of bacteriophage particles: Comparative analysis of the traditional plaque assay and real-time QPCR-and nanosight-based assays. Bacteriophage. 1, 86–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla N, Rojas MI, Cruz GNF, Hung S-H, Rohwer F, Barr JJ, 2016. Phage on tap-a quick and efficient protocol for the preparation of bacteriophage laboratory stocks. PeerJ 4, e2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns BJ, Timms AR, Jansen VA, Connerton IF, Payne RJ, 2009. Quantitative models of in vitro bacteriophage-host dynamics and their application to phage therapy. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BK, Abedon ST, Loc-Carrillo C, 2013. Phage cocktails and the future of phage therapy. Future Microbiol. 8, 769–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RY, Wong J, Mathai A, Morales S, Kutter E, Britton W, Li J, Chan H-K, 2017. Production of highly stable spray dried phage formulations for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 121, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RYK, Chen K, Wang J, Wallin M, Britton W, Morales S, Kutter E, Li J, Chan H-K, 2018. Proof-of-principle study in a murine lung infection model of antipseudomonal activity of phage PEV20 in a dry-powder formulation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 62, e01714–01717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RYK, Wallin M, Kutter E, Morales S, Britton W, Li J, Chan H-K, 2019. Storage stability of inhalable phage powders containing lactose at ambient conditions. Int. J. Pharm 560, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Okuda T, Lu X-Y, Chan H-K, 2016. Amorphous powders for inhalation drug delivery. Adv. Drug Del. Rev 100, 102–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Kourmatzis A, Mekonnen T, Gholizadeh H, Raco J, Chen L, Tang P, Chan H-K, 2019. Does upper airway deformation affect drug deposition? Int. J. Pharm 572, 118773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew NY, Chan H-K, 1999. Influence of particle size, air flow, and inhaler device on the dispersion of mannitol powders as aerosols. Pharm. Res 16, 1098–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew NY, Chan H-K, 2002a. Effect of powder polydispersity on aerosol generation. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 5, 162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew NY, Chan H-K, 2002b. The role of particle properties in pharmaceutical powder inhalation formulations. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv 15, 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates MS, Chan H-K, Fletcher DF, Raper JA, 2005. Influence of air flow on the performance of a dry powder inhaler using computational and experimental analyses. Pharm. Res 22, 1445–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates MS, Chan H-K, Fletcher DF, Raper JA, 2006. Effect of design on the performance of a dry powder inhaler using computational fluid dynamics. Part 2: air inlet size. J. Pharm. Sci 95, 1382–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P, Pereira C, Gomes AT, Almeida A, 2019. Efficiency of single phage suspensions and phage cocktail in the inactivation of Escherichia coli and Salmonella Typhimurium: an in vitro preliminary study. Microorganisms 7, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox C, Harris W, Lee J, 1974. Viability and electron microscope studies of phages T3 and T7 subjected to freeze-drying, freeze-thawing and aerosolization. Microbiology 81, 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer AH, Chan H, Price R, 2012. A critical view on lactose-based drug formulation and device studies for dry powder inhalation: which are relevant and what interactions to expect? Adv. Drug Del. Rev 64, 257–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, Russell DA, Ford K, Harris K, Gilmour KC, Soothill J, Deborah J-S, Schooley RT, 2019. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med 25, 730–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dini C, De Urraza PJ, 2013. Effect of buffer systems and disaccharides concentration on Podoviridae coliphage stability during freeze drying and storage. Cryobiology 66, 339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte J, Pereira C, Moreirinha C, Salvio R, Lopes A, Wang D, Almeida A, 2018. New insights on phage efficacy to control Aeromonas salmonicida in aquaculture systems: an in vitro preliminary study. Aquaculture 495, 970–982. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Kittler S, Klein G, Glünder G, 2013. Impact of a single phage and a phage cocktail application in broilers on reduction of Campylobacter jejuni and development of resistance. PLoS One 8, e78543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsevanishvili T, 1974. Certain methodological aspects of the use of inhalation of a polyvalent bacteriophage in the treatment of pneumonia of young children. Pediatric-Zhurnal G N Speranskogo 53, 65–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshahi L, Seed KD, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH, 2008. Toward modern inhalational bacteriophage therapy: nebulization of bacteriophages of Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv 21, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Liu X, Li Y, Han W, Lei L, Yang Y, Zhao H, Gao Y, Song J, Lu R, 2012. A method for generation phage cocktail with great therapeutic potential. PLoS One 7, e31698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D, 2015. The advantages of designing high-resistance swirl chambers for use in dry-powder inhalers, ONdrugDelivert Magazine. pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman P, Abedon ST, 2010. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance, Adv. Appl. Microbiol 70, 217–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain KK, 2008. The handbook of nanomedicine. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kutateladze á., Adamia R, 2008. Phage therapy experience at the Eliava Institute. Med. Mal. Infect 38, 426–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S, 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 8, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung SS, Parumasivam T, Gao FG, Carrigy NB, Vehring R, Finlay WH, Morales S, Britton WJ, Kutter E, Chan H-K, 2016. Production of inhalation phage powders using spray freeze drying and spray drying techniques for treatment of respiratory infections. Pharm. Res 33, 1486–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Leung SSY, Gengenbach T, Yu J, Gao GF, Tang P, Zhou QT, Chan H-K, 2017. Investigation of L-leucine in reducing the moisture-induced deterioration of spray-dried salbutamol sulfate power for inhalation. Int. J. Pharm 530, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Chang RYK, Britton WJ, Morales S, Kutter E, Li J, Chan H-K, 2019. Inhalable combination powder formulations of phage and ciprofloxacin for P. aeruginosa respiratory infections. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 142, 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margaret L, Experiments on shaking bacteriophage, J. Pathol. Bacteriol, 54 (1942) 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Maa Y-F, Nguyen P-AT, Hsu SW, 1998. Spray-drying of air-liquid interface sensitive recombinant human growth hormone. J. Pharm. Sci 87, 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matinkhoo S, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Finlay WH, Vehring R, 2011. Spray-dried respirable powders containing bacteriophages for the treatment of pulmonary infections. J. Pharm. Sci 100, 5197–5205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merabishvili M, Vervaet C, Pirnay J-P, De Vos D, Verbeken G, Mast J, Chanishvili N, Vaneechoutte M, 2013. Stability of Staphylococcus aureus phage ISP after freezedrying (lyophilization). PLoS One 8, e68797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MH, Surface inactivation of bacterial viruses and of proteins, J. Gen. Physiol, 31 (1948) 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafabadi AR, Gilani K, Barghi M, Rafiee-Tehrani M, 2004. The effect of vehicle on physical properties and aerosolisation behaviour of disodium cromoglycate microparticles spray dried alone or with L-leucine. Int. J. Pharm 285, 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SP, Chan H-K, 2020. In vitro-in vivo correlations (IVIVCs) of deposition for drugs given by oral inhalation. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega FL, Vlot M, de Jonge PA, Dreesens LL, Beaumont HJ, Lavigne R, Dutilh BE, Brouns SJ, 2018. Targeting mechanisms of tailed bacteriophages. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 760–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SC, Nakai T, 2003. Bacteriophage control of Pseudomonas plecoglossicida infection in ayu Plecoglossus altivelis. Dis. Aquat. Org 53, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C, Moreirinha C, Lewicka M, Almeida P, Clemente C, Cunha Â, Delgadillo I, Romalde JL, Nunes ML, Almeida A, 2016. Bacteriophages with potential to inactivate Salmonella Typhimurium: use of single phage suspensions and phage cocktails. Virus Res. 220, 179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira C, Silva YJ, Santos AL, Cunha Â, Gomes N, Almeida A, 2011. Bacteriophages with potential for inactivation of fish pathogenic bacteria: survival, host specificity and effect on bacterial community structure. Mar. Drugs 9, 2236–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope WH, Haase-Pettingell C, King J, 2004. Protein folding failure sets high-temperature limit on growth of phage P22 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 70, 4840–4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semler DD, Goudie AD, Finlay WH, Dennis JJ, 2014. Aerosol phage therapy efficacy in Burkholderia cepacia complex respiratory infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58, 4005–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HE, Lechuga-Ballesteros D, 2008. Spray drying: theory and pharmaceutical applications. tions In: Augsburger LL,and Hoag SW (eds). Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms: Tablets,Volume 1: Unit Operations and Mechanical Properties. InformaHealthcare, New York, NY; pp. 227–260. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SS, Flury M, Yates MV, Jury WA, Role of the air-water-solid interface in bacteriophage sorption experiments, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 64 (1998) 304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung SSY, Carrigy NB, Vehring R, Finlay WH, Morales S, Carter EA, Britton WJ, Kutter E, Chan H-K., 2019. Jet nebulization of bacteriophages with different tail morphologies–Structural effects, Int J Pharm. 554: 322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Yu A, Chan H-K, Yang R, 2015. Discrete modelling of powder dispersion in dry powder inhalers-a brief review. Curr. Pharm. Des 21, 3966–3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z, Zheng B, Yang R, Yu A, Chan H-K, 2013. CFD-DEM investigation of the dispersion mechanisms in commercial dry powder inhalers. Powder Technol. 240, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Trouwborst T, De Jong J, Winkler K, 1972. Mechanism of inactivation in aerosols of bacteriophage T1. J. Gen. Virol 15, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouwborst T, Kuyper S, De Jong J, Plantinga A, 1974. Inactivation of some bacterial and animal viruses by exposure to liquid-air interfaces. J. Gen. Virol 24, 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Jin Y, Bai F, Jin S, 2015. “Chapter 41 Pseudomonas aeruginosa” In: Molecular Medical Microbiology. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, pp. 753–767. [Google Scholar]