Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) play a critical role in shaping adaptive immunity. Systemic transfer of DCs by intravenous injection has been widely investigated to inform the development of immunogenic DCs for use as cellular therapies. Adoptive transfer of DCs to mucosal sites has been limited but serves as a valuable tool to understand the role of the microenvironment on mucosal DC activation, maturation and antigen presentation. Here, we show that chitosan facilitates transmigration of DCs across the vaginal epithelium in the mouse female reproductive tract (FRT). In addition, ex vivo programming of DCs with fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3-L) was found to enhance translocation of intravaginally administered DCs to draining lymph nodes (dLNs) and stimulate in vivo proliferation of both antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (cross-presentation). Mucosal priming with chitosan and DC programming may hold great promise to enhance efficacy of DC-based vaccination to the female genital mucosa.

Keywords: mucosal vaccine, dendritic cell, chitosan, reproductive tract, draining lymph node

1. Introduction

The development of prophylactic vaccines against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) has been marked by a few notable successes such as the human papillomavirus vaccine [1], but there are still no effective vaccines for many STIs including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [2]. Women are disproportionately impacted by STIs and HIV, which can also have long-term consequences on their fertility and infant morbidity/mortality [3]. Vaccines that elicit protective immunity in the female reproductive tract (FRT) could inhibit sexually transmitted pathogens at the portal of entry [2], but these induction mechanisms are still not well understood. Systemic immunization through the parenteral, oral, or intranasal route has shown limited capacity to induce immunity in the vaginal mucosa against STIs. In contrast, vaginal immunization has been shown to elicit greater and more robust antigen-specific humoral and cellular immunity [4, 5]. This observation may be explained in part by the immunologically restrictive mucosal tissue in the FRT, which lacks local organized lymphoid structures equivalent to those found in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts [6]. As a consequence, it is generally accepted that antigens must be transported across the vaginal epithelium to inductive sites in draining iliac (ILLNs) and inguinal lymph nodes (IGLNs) where T cells are primed and disseminate to generate local and systemic immunity [6, 7]. Studies of intravaginal (IVG) immunization have shown that antigen-specific memory T cells, which are indispensable for efficient protective immunity at the site of infection, are recruited to the vaginal tissue to a much higher extent compared to systemic immunizations [5]. As such, protective immune responses have been shown to be strongest at and proximal to the site of the vaginal mucosal immunization [8].

Mucosal vaccine form and composition also impact the quantity and quality of the mucosal immune response. In situ delivery of soluble or particulate antigens is hampered by continuous bulk flow of the mucosal fluid [8, 9], enzymes [10], and the low frequency of mucosal dendritic cells (DCs) [11]. Classical vaccine protocols have frequently shown suboptimal protection due to poor systemic delivery of antigen and adjuvant to DCs in vivo [12], which limits bioavailability and subsequent vaccine efficacy [13]. Alternatively, adoptive transfer of autologous DC subsets programmed and loaded with antigen ex vivo has been developed as cellular therapies and shown some success. For instance, systemic transfer of DCs primed ex vivo with pathogen or tumor antigens induces anti-microbial and anti-tumor immunity [14, 15]. Once DCs are activated and programmed ex vivo, they have the capacity to elicit protective immunity in the absence of additional adjuvants [16], which may be beneficial in mucosal vaccines where strong adjuvants are typically needed to overcome the immunosuppressive environment [17]. DCs adoptively transferred onto the sublingual mucosa have been found to accumulate in distal lymphoid organs after systemic circulation [18]. Programmed DCs transferred intranasally have also been shown to induce IFN-γ secretion from T cells in draining lymph nodes (dLNs) [19]. Both studies provide important premise that programmed DCs can be adoptively transferred to mucosal sites, migrate and induce cellular responses. However, safely and effectively maximizing the translocation of these therapeutic immune cells across the mucosal epithelium remains a formidable challenge and will be necessary to prime subsequent immunity [20]. In addition, no studies to date have demonstrated that programmed DCs adoptively transferred to mucosal surfaces directly prime and activate T cells.

An important challenge in the development of DC-based mucosal vaccines is to induce DCs to cross the epithelial barrier and reach the dLNs, where they can activate T cells. DCs have been observed to creep through tight junctions of a single layer of gut epithelium to sample pathogens [21], and activated Langerhans cells (LCs) in the multilayered vaginal epithelium have been shown to transmigrate across the epithelium to the dLNs [17]. Studies investigating the transmigration of exogenous leukocytes across the mouse vaginal epithelium to the dLNs have been very limited. In one study, lymphoid cells comprised of T/B lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells were collected from the peritoneal cavity of donor mice and administered intravaginally to recipient mice [22]. Of the total 5–10×106 cells administered, only 8~9 donor cells excluding macrophages were found in the draining ILLNs 24 hour post-administration.

A separate study administered murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) pulsed with herpes simplex virus (HSV) antigen to the mouse vaginal tract [23], but did not observe DC translocation to the dLNs or subsequent protective immunity against HSV challenge. Chitosan, a natural and safe product, has been used as a mucosal adjuvant and shown to affect epithelial cell tight junctions by electrostatic charge interactions [24]. We previously found that chitosan priming of the mouse vaginal mucosal surface enhances paracellular permeability of nanoparticles across the vaginal epithelium without inducing significant inflammatory responses [25]. Based on this observation, we performed a pilot study wherein the mouse vaginal mucosa was primed with chitosan prior to administration of BMDCs, and found that chitosan facilitated transmigration of adoptively transferred cells to the dLNs. However, strategies that ex vivo prepare DCs to be adoptively transferred to the vaginal mucosa are still required to overcome immunosuppressive environment and multilayered epithelium barrier in the female genital mucosa to inform new cellular immunotherapies to shape both local and systemic immunity.

Here, we demonstrate BMDCs that are ex vivo programmed and intravaginally administered lead to optimal T cell proliferation in LNs that drain the FRT. There are two representative BMDC programming methods using cytokines of murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) or human fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3-L) [26]. And, BMDCs derived with these two cytokines have exhibited phenotypes and inflammatory/migratory functions different each other [26]. Based on this, we hypothesized that unique programming of adoptive DCs is required for their phenotypic, migratory, and functional capabilities in the dLNs. We show that these BMDCs induced in vivo proliferation of both antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by DC programming-dependent manner. In detail, programmed BMDCs differentially exhibited capacity for transepithelial migration, antigen delivery and induction of antigen-specific T cell proliferation, including cross-presentation of protein antigen model, in the dLNs. Specifically, the in vivo cross-presentation was significantly enhanced by select DC-programming method. These findings provide evidence that DC-based immunization via the female genital mucosa is feasible for both local and systemic protective immunity through dLNs.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Murine GM-CSF and human Flt3-L (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) were used to derive BMDCs from mouse bone marrow. CpG-Oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN), polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [Poly(I:C)], monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA) (all from Invivogen, San Diego, CA), and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) were used as adjuvants to induce maturation of BMDCs. Ovalbumin (OVA, model protein antigen unless specified otherwise) (EndoFit, Invivogen), fluorescently (Alexa Fluor 555)-labeled OVA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), or OVA (257–264) SIINFEKL peptide (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA) was used as a model antigen. Ultra-pure chitosan (MW <200 kDa, deacetylation > 75%, NovaMatrix, Sandvika, Norway) was used to prime the mouse vaginal tract.

2.2. Preparation of BMDCs

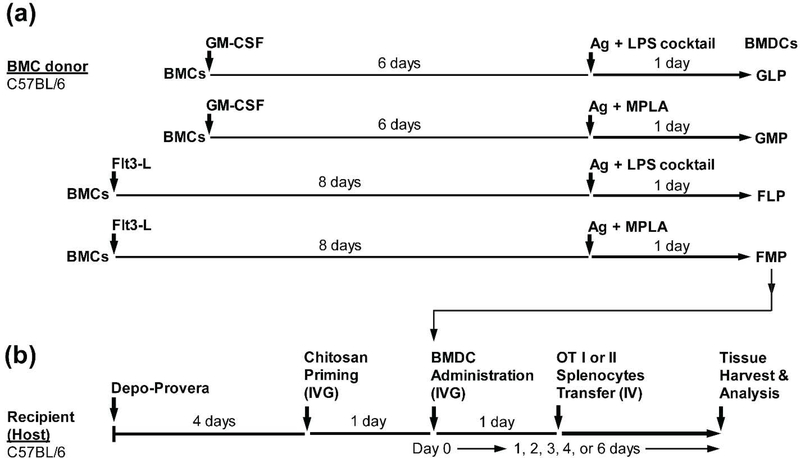

BMDCs were generated using GM-CSF or Flt3-L as previously described [26] with minor modifications and subsequently treated with antigen (OVA protein or SIINFEKL peptide) at 500 μg/ml and adjuvant – LPS cocktail [LPS at 1 μg/ml, CpG-ODN at 10 μg/ml, and Poly(I:C) at 10 μg/ml] or MPLA at 10 μg/ml – for the preparation of 4 different types of BMDC (GLP, GMP, FLP, or FMP) as shown in Figure 1a. Briefly, bone marrow was collected from femurs and tibias of hind limbs of 8~10-week-old female C57BL/6 (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). After red blood cells were lysed, cells were washed twice using PBS. Then, cells were plated/differentiated under cell culture conditions different between GM-CSF-based BMDCs and Flt3-L-based BMDCs. For GLP or GMP, cells were plated into Petri dishes (100-mm diameter) at 5 × 105 cells/ml of a RPMI-1640-based complete medium and 20 ng/ml GM-CSF. Three and five days later, the medium was refreshed with GM-CSF and subsequently added with antigen/adjuvant during the last 24 hours of 7-day culture period. For FLP or FMP, cells were plated into 6-well plate at 1 × 106 cells/ml of complete medium and 200 ng/ml Flt3-L. Then, cells were left without disturbance and subsequently added with antigen/adjuvant during the last 24 hours of the 9-day culture period. After 24-hour treatment with antigen/adjuvant, all types of BMDCs were collected and extensively washed twice using PBS for IVG administration to mice (Figure 1b). Since the final BMDC products were intravaginally administered without further CD11c+ cell isolation, ‘BMDCs’ in the study presented herein indicate a mixture of CD11c+ and CD11c− cells.

Figure 1. BMDC programming and study time line.

(a) Schematic of ex vivo derivation and activation of BMDCs. Bone marrow cells (BMCs) harvested from C57BL/6J mice were treated ex vivo with GM-CSF or Flt3-L for 6 or 8 days, respectively. Cells were pulsed with Ag (antigen, OVA protein or SIINFEKL peptide) and adjuvant (LPS cocktail or MPLA) for the last 24 hours followed by cell collection. BMDCs were classified based on the differentiation factor (GLP, GMP, FLP, or FMP) used in each programming method. (b) Schematic of treatment study design. Depo-Provera was administered to recipient (host) mice prior to chitosan priming followed by IVG administration of BMDCs and IV transfer of splenocytes collected from OTI or OTII transgenic mice.

2.3. In vivo IVG administration of BMDCs to recipient (host) mice

All procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In vivo administration of reagents and materials to mice is summarized in Figure 1b. Briefly, 8~10-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were subcutaneously administered 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera, Greenstone LLC, Peapack, NJ) formulated in PBS (100 μl) per recipient (host) mouse in order to synchronize the estrous cycle. Four day post-Depo-Provera administration, mice were anesthetized and vaginal tracts were lavaged three times with 80 μl of PBS, and subsequently swabbed using a sterile calginate swab to remove mucus. Then, mice were intravaginally administered 1% (w/v) chitosan formulated in endotoxin-free water (20 μl per mouse). Twenty four hours later, vaginal tracts of anesthetized mice were lavaged and swabbed as described above, and then 8 × 105 BMDCs suspended in 20 μl of PBS were intravaginally administered per mouse. Mice in the negative control group were intravaginally administered 20 μl of PBS without BMDCs, non-fluorescently labeled BMDCs, non-antigen-pulsed BMDCs, non-migratory dead BMDCs (which were fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde), or antigen-pulsed BMDCs without chitosan priming. To test if the cell-free fraction of the final suspension of 800,000 BMDCs in 20 μl PBS for IVG administration contributes to antigen-specific T cell proliferation in host dLNs, this final suspension was additionally spun and 20 μl of the supernatant was intravaginally administered (SOL). Mice were kept anesthetized in dorsal recumbence for 30 minutes following all IVG administrations to minimize external leakage. To prevent self- and inter-grooming, mice were taped around their abdomen with FisherBrand tape and individually caged from the day of chitosan priming through the end point (Figure 1b). Mice were euthanized at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 6 day post-BMDC IVG administration, and organs were isolated and processed for fluorescence imaging, flow cytometry, or immunohistochemistry.

2.4. In vivo adoptive transfer of antigen-specific T cells (responders)

As sources of antigen-specific T cells, 8~10-week-old female OTI or OTII transgenic mice (hemizygous unless specified otherwise, Jackson Laboratory) were used. Total splenocytes were collected from the transgenic mice and subsequently labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. After extensive washing with PBS, CFSE-labeled 12 × 106 splenocytes resuspended in 400 μl of PBS were transferred per host mouse via IV route (tail vein) for in vivo antigen-specific T cell proliferation in dLNs. Only a single experiment was performed using pure antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that were isolated from total splenocytes of OTI mice (homozygous) using a CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. In this experiment, 2.4 × 106 CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells were adoptively transferred per host mouse based on our observation that pure CD8+ T cells were found to be 20% of total OTI splenocytes before isolation procedure (data not shown). In this study, we adoptively transferred total splenocytes of OTI or OTII transgenic mice to the host mice without pre-isolation of antigen-specific T cells, unless specified otherwise, as these TCR transgenic mouse cells are not necessarily purified prior to in vivo transfer for its specific response to OVA peptides [27].

2.5. Fluorescence imaging of cell translocation

At times specified in Figure 1b, organs isolated from euthanized mice were placed on a black construction paper and imaged using a Xenogen in vivo imaging system (IVIS) (Xenogen Corporation, Alameda, CA) to evaluate translocation of fluorescently labeled (CFSE) BMDCs or splenocytes following IVG administration or IV transfer, respectively. Fluorescence was normalized to the negative control groups (administered PBS or non-fluorescently labeled cells) to set a minimum threshold for tissue auto-fluorescence for each independent trial. Following this normalization to the control, number of fluorescence (CFSE)-positive or negative LNs was counted for all ILLNs or IGLNs per time point, and % of CFSE+ or CFSE− LN number out of a total of 6 or 12 LNs was calculated. In addition, using LivingImage 3.0 software, a region of interest (ROI) encompassing the fluorescent area was defined and the average radiance (photon/second/cm2/steradian) of each organ was obtained. The average radiance per organ was normalized to the radiance of organs from the negative control group per trial with 3 ~ 6 host mice.

2.6. Statistical analysis

To observe significant differences between control and treatment groups, various statistical analysis methods were used. T-test corrected by multiple comparison using the Holm-Sidak method or Mann-Whitney U test, or one-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used depending on experimental data sets. For all statistical methods, GraphPad PRISM (Version 5.04, La Jolla, CA) was used. Unless otherwise indicated, a p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Other methods are also detailed in the Supplemental Materials.

3. Results

3.1. Flt3-L enhances transmigration of BMDCs to the draining lymph nodes

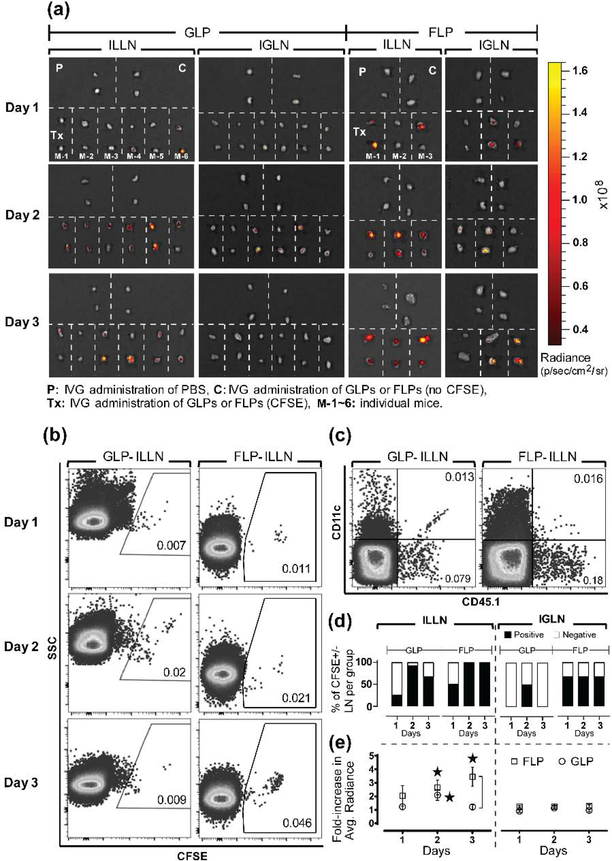

Based on our previous findings showing enhanced transport of intravaginally delivered nanoparticles [25], we show that adoptively transferred DCs migrate to dLNs following chitosan priming of the vaginal mucosa. The pilot study showed that chitosan priming and administration of GM-CSF-derived BMDCs that were LPS cocktail-matured and fluorescently labeled with CFSE (GLP-CFSE) led to all mice having at least a single CFSE-positive dLN (Supplemental Figure 1). To further understand how ex vivo programming protocols direct cell translocation and function, we compared GLP-CFSE to BMDCs that were derived with Flt3-L, matured with LPS cocktail, and fluorescently labeled with CFSE (FLP-CFSE). We observed by fluorescence and flow cytometry that both FLP-CFSE and GLP-CFSE translocated to draining ILLNs and IGLNs over time (Figure 2a, 2b). Consistent with the pilot study above, fluorescence LN images for GLPs did not exhibit CFSE+ signals from many IGLNs (Figure 2a). We also confirmed translocation of adoptively transferred FLP and GLP CD45.1+CD11c+ cells to the dLNs of CD45.2+ (CD45.1−) host mice (Figure 2c). Whole organ fluorescence imaging of the FRT suggests that FLP-CFSE have better attachment or penetration into the vaginal mucosa compared to GLP-CFSE (Supplemental Figure 2). Based on the raw imaging data quantifying the percent CFSE-positive lymph nodes per treatment group as a measure for adoptive cell migration to target LNs (Figure 2a), FLPs exhibited more positive ILLNs and IGLNs at all time points compared to GLPs (Figure 2d). FLP-CFSE also exhibited 3-fold higher fluorescent intensity per ILLN compared to GLP-CFSE on day 3 (Figure 2e), which suggests a larger amount of translocating cells per LN. In summary, we show that BMDC translocation from the vaginal mucosa is modulated by ex vivo programming with different cytokines.

Figure 2. Flt3-L enhances BMDC translocation to dLNs following IVG administration.

(a) Image overlay of whole organ tissue fluorescence and photograph of ILLN and IGLN excised from host mice 24, 48, or 72 h post IVG administration of GLPs or FLPs fluorescently labeled with CFSE (GLP-CFSE or FLP-CFSE, respectively). Each section separated by white dotted line represents a pair of LNs collected from one host mouse for indicated treatments. P: control mice intravaginally administered with PBS, C: control mice intravaginally administered with GLPs or FLPs not labeled with CFSE, Tx: treatment mice intravaginally administered with GLPs or FLPs labeled with CFSE, M-1~6: individual mice are numbered. A total of 3 or 6 host mice were examined per time point following IVG administration of FLP-CFSE or GLP-CFSE, respectively. (b-c) Representative flow cytometry observations of detecting the presence of GLPs or FLPs in dLNs of host mice following IVG administration. Four LNs from each time point that showed relatively higher fluorescence intensity in (a) were selected, combined, and processed for flow cytometry analysis. Representative dot plots show frequency (%) of (b) GLP-CFSE or FLP-CFSE in host ILLNs for all 3 days after IVG administration to host mice and (c) CD45.1+CD11c+ double-positive GLPs or FLPs 2 day post-IVG administration to CD45.2+ (CD45.1−) host. Numbers in each gate indicate frequency (%) of the gated cells out of the total tissue cells digested from host ILLNs. (d-e) Translocation of GLP-CFSE or FLP-CFSE from vaginal tract to dLNs of host mice as shown in (a) was quantified by (d) Fluorescence (CFSE)-positive or negative LN count per group per time point and frequency (%) of the LN count, and (e) Average tissue radiance normalized to non-fluorescent cell control (see quantification details in Methods). Data show mean ± SD of all LNs collected from n = 3 or 6 mice per time point. For statistical analysis, T-test corrected by multiple comparison using the Holm-Sidak method was used, and asterisk (*) indicates significant difference compared to non-fluorescence cell control and bracket indicates significant difference between two treatments (p ≤ 0.05).

3.2. Flt3-L enhances BMDC transepithelial migration, antigen association, activation, and accumulation in the draining lymph nodes

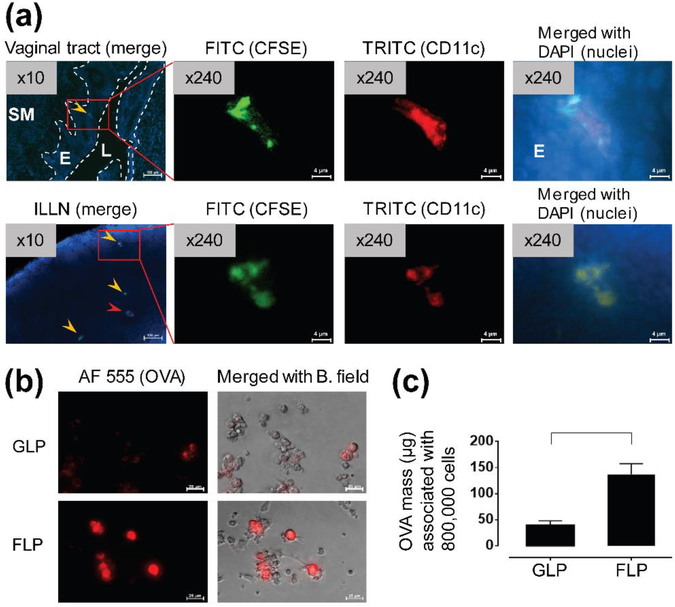

To visualize single cell-based transepithelial migration and antigen (OVA)-association of BMDCs, we performed an immunofluorescence imaging process under microscope (Figure 3). As a result, we detected CD11c+ FLP-CFSE that had transmigrated across the vaginal epithelium and subsequently translocated to the dLNs (Figure 3a). When BMDCs were pulsed with OVA at the same time as LPS cocktail treatment, FLPs showed 3.5-fold greater association with OVA than GLPs (Figure 3b, 3c).

Figure 3. Intravaginally administered FLPs transmigrate to dLNs across vaginal epithelium and Flt3-L promotes association with OVA.

(a) Representative fluorescent images of translocation of intravaginally administered FLP-CFSE to the dLN (ILLN) 2 day post-IVG administration to host mice. Translocation of administered FLP-CFSE was confirmed by co-localization (yellow arrow head) of fluorescence from CFSE (green), CD11c (red), and nuclei (blue, DAPI). Red arrow head indicates non-CFSE-labeled host CD11c+ cells. SM: submucosal tissue, E: epithelium (vaginal), L: lumen (vaginal). Images were examined under 10× objective lens and then selected areas were further examined under 40× objective lens. These 40× images were additionally magnified by 6× (digital magnification). Scale bars indicate 100 μm or 4 μm for or 10× or 240× images, respectively. (b) Representative fluorescence images of fluorescently labeled (Alexa Fluor 555)-OVA associated with GLPs or FLPs following antigen pulsing for 24 hours. Scale bars indicate 25 μm for 40× objective lens. AF 555: Alexa Fluor 555, B. Field: bright field. (c) Quantification of OVA associated with 800,000 GLPs or FLPs to be intravaginally administered to a single host mouse. Data show mean ± SD of GLPs or FLPs derived from n = 3 mice. For statistical analysis, T-test corrected by multiple comparison using the Mann-Whitney test was used and bracket indicates significant difference between two treatments (p ≤ 0.05).

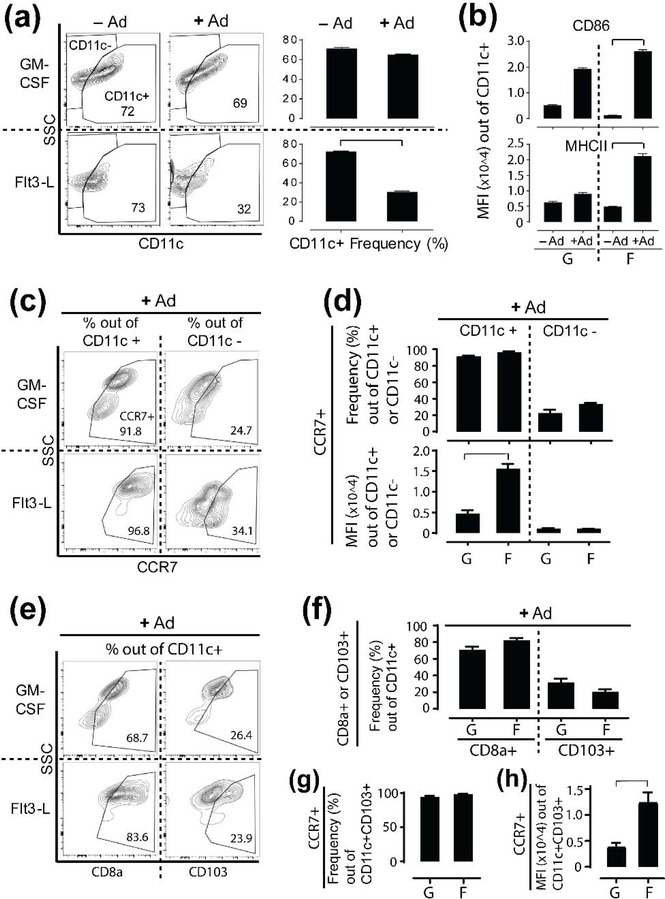

To identify subsets of the ex vivo programmed BMDCs and determine if they are appropriately activated for antigen presentation and migration, we measured expression of various DC surface molecules using flow cytometry (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 3). We observed that treatment with LPS cocktail had no effect on CD11c+ GLP frequency but reduced the frequency of CD11c+ FLPs (Figure 4a). Despite this reduction, CD11c+ FLPs exhibited significantly increased expression of single positive CD86+ or MHCII+ by 4–20 fold (Figure 4b), and double positive CD86+MHCII+ expression by two-fold upon LPS cocktail treatment (data not shown). In contrast, CD11c+ GLPs had no statistically significant change in these same activation markers. In summary, we demonstrate that Flt3-L and GM-CSF differentially induce activation and antigen association of CD11c+ BMDCs, which are essential to proliferation of antigen-specific T cells.

Figure 4. Flt3-L promotes BMDC activation and CCR7 upregulation on CD11c+ or CD11c+CD103+ BMDCs.

(a-b) Flow cytometry analysis for (a) Frequency (%) change of CD11c+ GM-CSF-programmed or Flt3-L-programmed BMDCs out of total live cells (numbers in gates indicate frequency of CD11c+ cells) and (b) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD86 or MHCII expression on those CD11c+ cells upon Ad (adjuvant, LPS cocktail) treatment for 24 hours. Once BMDCs are treated with Ad here, they are GLPs (G) or FLPs (F) as defined in Figure 1a. (c-d) Flow cytometry analysis for (c, d-top) Frequency (%) change of CCR7+ cells out of total CD11c+ or CD11c− GLPs or FLPs and (d-bottom) MFI of CCR7 expression on CD11c+ or CD11c− GLPs or FLPs. (e-h) Flow cytometry analysis for (e, f) Frequency (%) change of CD8α+ or CD103+ cells out of total CD11c+ GLPs or FLPs. (g) Frequency (%) change of CCR7+ cells out of total CD11c+CD103+ GLPs or FLPs. (h) MFI of CCR7 expression on CD11c+CD103+ GLPs or FLPs. Data show mean ± SD of GLPs or FLPs derived from n = 3 mice. For statistical analysis, T-test corrected by multiple comparison using the Mann-Whitney test was used and bracket indicates significant difference between two treatments (p ≤ 0.05).

In addition, we found that the frequency of B220+ plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and B220− conventional DCs (cDCs) were similar between GLPs and FLPs (Supplemental Figure 3a, 3b). The cDC population for both GLPs and FLPs included cell subsets of CD8α+, CD103+, CD11b+, and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα)+ (Supplemental Figure 3c, 3d). Among the GLP cDC subsets, CD103+ cell frequency was lower than other subsets whereas FLP cDC subsets showed higher CD8α+ cell frequency compared to other subsets. However, there was no significant difference measured between CD103+ or CD8α+ GLPs and FLPs. CCR7+ cell frequencies were similar between pDCs and cDCs for GLPs and FLPs (Supplemental Figure 3e). Interestingly, pDCs exhibited significantly higher per-cell density of CCR7 expression on FLPs as compared GLPs (Supplemental Figure 3f). We measured similar CCR7+ cell frequencies between the CD11c+ or CD11c− populations of GLPs and FLPs (Figure 4c, 4d). However, CD11c+ FLPs showed thee-fold higher expression of CCR7 compared to CD11c+ GLPs (Figure 4d). Although the frequencies of CD8α+ or CD103+ GLPs and FLPs were similar (Figure 4e, 4f ), we found higher frequencies of CD11c+CD8α+ subsets than CD11c+CD103+ subsets for both GLPs and FLPs (Figure 4f). Since the migratory capacity of non-lymphoid tissue/migratory CD103+ DCs largely relies on CCR7 upregulation [28], we further investigated CCR7 expression on CD11c+CD103+ cells. Again, while frequencies of CCR7+ cells for CD11c+CD103+ were very similar between GLPs and FLPs, CCR7 expression density on CD11c+CD103+FLPs was three-fold higher than GLPs (Figure 4g, 4h). Collectively, while frequencies of various DC subsets between GLPs and FLPs are very similar each other, CD11c+ or CD11c+CD103+ FLPs show greater CCR7 expression compared to GLPs, which may have implications for their migratory potential to dLNs.

3.3. Intravaginally administered BMDCs induce OVA-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in the draining lymph nodes

In separate experiments, we confirmed that the location of antigen-specific T cells in both draining ILLNs and IGLNs of host mice 24 hour post-adoptive transfer (IV route) of CFSE-labeled OTII splenocytes to the host mice as seen in Supplemental Figure 4. We also directly compared simple gates (CFSE+CD4+ or CFSE+CD8+) and multiple gates (CFSE+CD11c−CD8−CD3+ or CFSE+CD11c−CD4−CD3+, respectively) and show there is no difference of CFSE dilution frequencies between those two different gating methods (Supplemental Figure 5). As such, we expect that the CFSE+CD4+ or CFSE+CD8+ cell gate accurately captures CFSE dilution resulting from antigen-specific T cell proliferation.

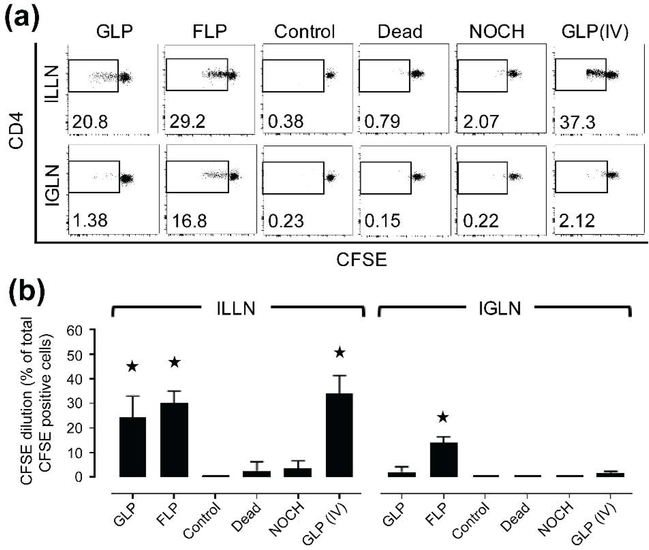

To investigate if BMDCs translocating from the vaginal tract to the dLNs can functionally stimulate OVA-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs, we intravenously transferred total splenocytes from OVA-specific transgenic mice (OTII responders) into host mice as described in Figure 1. We found that FLPs induced CD4+ T cell proliferation in both ILLNs and IGLNs on day 4 at levels significantly higher than the negative control programmed without OVA (antigen). In contrast, GLPs induced significantly higher CD4+ T cell proliferation only in the ILLNs (Figure 5a, 5b). Additional controls were prepared to inhibit the migratory capacity of GLPs by fixation (Dead group) or by not priming the vaginal mucosa with chitosan (NOCH group). Similar to our negative control, Dead and NOCH groups did not induce significant CD4+ T cell proliferation (Figure 5a, 5b) in either the ILLNs or IGLNs. As expected, a positive control of GLPs administered intravenously induced CD4+ T cell proliferation. In addition, dynamics of CD4+ T cell proliferation and host CD11c+ cell recruitment to the dLNs upon BMDC transmigration were examined only using GLPs. Interestingly, although GLPs did not induce significant CD4+ T cell proliferation on day 4 in the IGLNs, they induced CD4+ T cell proliferation that increased significantly over time by day 6 (Supplemental Figure 6a). We also observed that IVG administration of GLPs promoted recruitment of host (endogenous) CD11c+ cells to the ILLNs over time (Supplemental Figure 6b, 6c). In conclusion, BMDC translocation to the dLNs is required for antigen-specific T cell proliferation, which is a dynamic process that also leads to recruitment of host (endogenous) CD11c+ cells to the dLNs.

Figure 5. Antigen-pulsed BMDCs, upon translocation to dLNs, stimulate antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation.

(a-b) Flow cytometry observations of in vivo antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in host dLNs 4 day post IVG administration of various BMDCs are shown by (a) Representative CFSE dilutions of CD4+ cells (numbers in dot plots indicate CFSE-diluted cell fraction out of total CFSE+CD4+ cells) and (b) Quantification of those CFSE dilutions of CD4+ cells gated from total tissue cells digested from draining ILLNs and IGLNs of the host mice. Dead (control): GLPs that were fixed with 1% PFA, NOCH (control): GLPs administered without chitosan priming, GLP (IV) (control): GLPs administered via IV route. Control: GLPs without antigen-pulsing. As another control of FLPs without antigen-pulsing has also been found to induce minimal T cell proliferation in the same way as Control (GLPs without antigen-pulsing) above, the Control shown in the figure is representative for both GLP and FLP. Data show mean ± SD of all LNs collected from n = 3~6 mice. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used and asterisk (*) indicates significant difference compared to control (p ≤ 0.05).

3.4. Flt3-L enhances capacity of intravaginally administered BMDCs to induce OVA-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in the draining lymph nodes

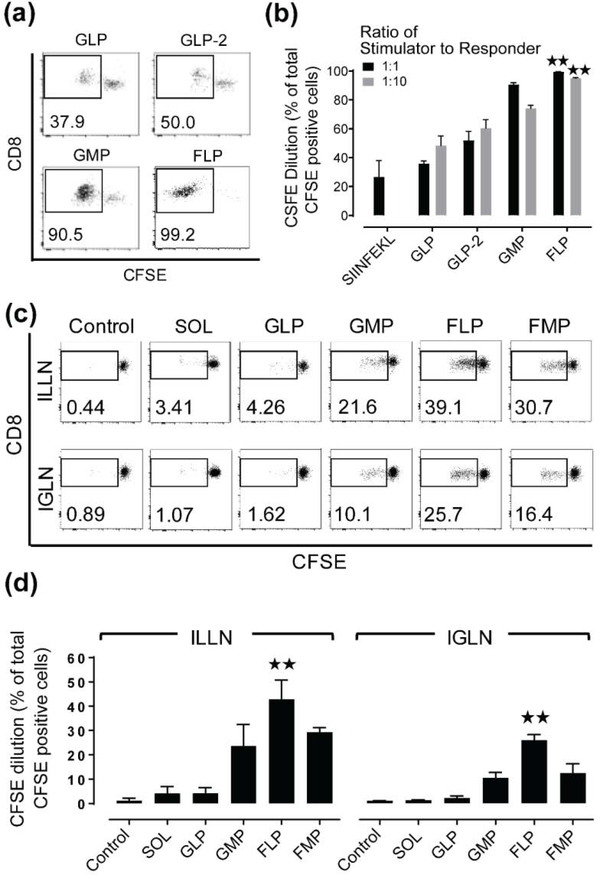

OVA-specific transgenic mice (OTI) were used to measure an antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response to an adoptive transfer of OVA-pulsed BMDCs to the vaginal mucosa. We first co-cultured stimulator (various BMDCs) and responder (total OTI splenocytes) cells in vitro to investigate how BMDC programming modulates cross-presentation. Compared to control (GLPs dosed with SIINFEKL at 500 μg/ml) or GLPs (dosed with OVA at 500 μg/ml), increasing the antigen dose by 2-fold (GLP-2) or using MPLA (GMP) instead of LPS cocktail resulted in higher OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation irrespective of the ratio of stimulator to responder cells (Figure 6a, 6b). However, FLPs (dosed with OVA at 500 μg/ml) induced OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation at the highest levels and was the only programming protocol that induced significantly higher T cell proliferation compared to GLPs for both ratios of stimulator and responder cells. Using these programming methods, and additional BMDCs that were programmed with both Flt3-L and MPLA (FMP), we next investigated their in vivo capacity to induce OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs following adoptive transfer to the vaginal mucosa. We observed that GLPs induced OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation similar to the negative controls, whereas GMPs induced an increasing trend of the proliferation in both ILLN and IGLN. Consistent with our in vitro findings, FLPs induced the highest level of OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation in both the ILLN and IGLN compared to all other programmed BMDCs (Figure 6c, 6d). In summary, we found that GLPs in vivo had no capacity to induce OTI CD8+ T cell proliferation but FLPs retained a high capacity to induce it in the dLNs. These results emphasize that DCs can be ex vivo programmed and pulsed with protein antigens, which derive multiple target antigenic epitopes, to elicit robust cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-based cellular immunity of the host.

Figure 6. Flt3-L enhances capacity of BMDCs to induce antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in dLNs.

(a-b) Flow cytometry observations of in vitro stimulation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation upon co-culture with various BMDCs were shown by (a) Representative CFSE dilutions of CD8+ cells and (b) Quantification of those CFSE dilutions of CD8+ cells gated from a pool of stimulators (various BMDCs) and responders (OTI splenocytes) following 70 hours of in vitro co-culture. SIINFEKL: positive control using SIINFEKL peptide-pulsed GLPs, GLP-2: higher dose (2×) of OVA antigen by additional OVA protein present in the co-culture wells. Data show mean ± SD of BMDCs derived from n = 3~4 mice. (c-d) Flow cytometry observations of in vivo antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in host dLNs 4 day post IVG administration of various BMDCs are shown by (c) Representative CFSE dilutions of CD8+ cells (numbers in dot plots indicate CFSE-diluted cell fraction out of total CFSE+CD8+ cells) and (d) Quantification of those CFSE dilutions of CD8+ cells gated from total tissue cells digested from draining ILLNs and IGLNs of the host mice. SOL: cell-free PBS fraction isolated from the final 800,000 cell/PBS (20 μl) suspension for IVG administration. Control: GLPs without antigen-pulsing. As another control of FLPs without antigen-pulsing has also been found to induce minimal T cell proliferation in the same way as Control (GLPs without antigen-pulsing) above, the Control shown in the figure is representative for all BMDCs. Data show mean ± SD of all LNs collected from n = 3~4 mice. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparison test was used and asterisk (*) indicates significant difference compared to GLP (in vitro co-culture) or control (in vivo) (**: p ≤ 0.01).

4. Discussion

We demonstrate for the first time that ex vivo programmed BMDCs administered to the mouse vaginal tract translocate to draining ILLNs and IGLNs where they induce antigen-specific T-cell proliferation. BMDC translocation and subsequent stimulation of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs were dependent on the use of chitosan to prime the vaginal epithelium and on the ex vivo BMDC programming method. It is well known that chitosan opens epithelial cell tight junctions by electrostatic interactions between the cationic chitosan and the negatively charged cell surface [24]. Previous work from our lab investigating nanoparticle transport in the vaginal mucosa showed that sequential rather than concurrent administration of chitosan and nanoparticles led to greater accumulation in dLNs [25]. For this reason, to maximize BMDC translocation across the vaginal epithelium, we sequentially primed the mucosal surface with chitosan and administered BMDCs. We found that chitosan was necessary for BMDC migration to dLNs (Supplementary Figure 1) and, although the direct mechanism is to be determined, the effect of chitosan on cell tight junctions likely also contributes to enhanced BMDC transmigration across the vaginal epithelium.

Unlike intravaginally administered DCs, we did not observe T cell proliferation in the IGLNs after GLPs were intravenously administered, presumably due to absence of DC homing to IGLNs following IV transfer of DCs [29]. We also observed nearly no proliferation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells when BMDC transmigration was inhibited (through DC fixation or no chitosan priming), even though these cells retained the ability to present OVA peptides to T cells upon direct contact [30]. Finally, we show that IVG administration of only the cell-free fraction (SOL), which was isolated from the final BMDC suspension to be intravaginally administered, was insufficient to induce antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs (Figure 6c, 6d). These collective observations support that intravaginally administered BMDCs are required to translocate to the dLNs for antigen-specific T cell proliferation in this study. We also show that, compared with BMDCs programmed with GM-CSF, Flt3-L-programmed BMDCs exhibited a higher frequency of translocation to the dLNs, had enhanced activation and association with a model antigen, and resulted in much greater antigen-specific stimulation of the dLN CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation. Since all of those DC functions are essential to vigorous adaptive immunity, Flt3-L-based DC programming possibly can make significant advance in cell-based immunotherapy. The soluble factors used to create DCs ex vivo from bone-marrow cells can profoundly impact the migratory and antigen-presenting capacities of the resulting DCs [26]. Previous studies have shown that Flt3-L-programmed BMDCs migrated more effectively to dLNs in vivo following subcutaneous administration to the mouse footpad [26] and DCs harvested from mice systemically injected with soluble Flt3-L exhibited enhanced in vitro antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in co-culture [31]. We applied the findings from these previous studies to uniquely program DCs for adoptive transfer to and migration from type II mucosa into dLNs to functionally activate effector T cell proliferation.

We assessed DC transmigration to the dLNs by IVIS imaging and quantifying the percent positive lymph nodes (Figure 2d), which is a binary measure for adoptive cell migration to target LNs, and relative lymph node fluorescence (Figure 2e), which is a continuous measure for adoptive cell accumulation in target LNs. Although we observed that GLP and FLP programming led to differences in the dynamics of their accumulation in dLNs, our results clearly demonstrate significant migration of programmed DCs to ILLN by day 2 (e.g., 100% ILLN are CSFE+). Secondary outcome measures of average radiance (Figure 2e) as well as antigen-specific T cell proliferation (Figure 5 and Figure 6) also support our claim that ex vivo programmed DCs adoptively transferred to the vaginal mucosa reach the dLNs. We observed that some mice did not exhibited fluorescently labeled BMDC accumulation in the dLNs whereas others did at the same time points (Figure 2a, 2d). Furthermore, our measured response is comparable to other published data where CFSE-labeled GM-CSF-derived or Flt3-L-derived BMDCs subcutaneously injected to a mouse footpad transmigrated to the dLNs at levels less than 0.05% or 0.25%, respectively [26]. In comparison, we observed CFSE-labeled BMDCs in the dLN (Figure 2a) of up to 50–100% and frequencies of donor BMDCs (0.013%, GLP and 0.016%, FLP of CD45.1+CD11c+ cells) out of whole dLN tissue cells (Figure 2c). Our results are remarkable given the different tissue barriers and location of the dLNs from the site of administration – subcutaneous injection provides direct access to lymph circulation, whereas DCs administered onto the surface of the vaginal mucosa require transmigrate across the thick epithelium to access lymph circulation and drain into the LNs. Between days 2 and 3, we observe that GLP treated animals showed a decrease in the percent positive IGLN (Figure 2d) and a reduction in the relative fluorescence in the ILLN (Figure 2e), whereas no significant change was observed for FLP treated animals. Based on the fact that the vaginal canal is drained by the ILLN and IGLN in descending order (in a time course) from the FRT [32], we speculate that fewer fluorescent GLPs migrated to ILLNs compared to FLPs. In addition, not all of the migratory GLPs successfully translocated further into the IGLNs at levels close to the negative control of PBS or BMDC without the CFSE label.

Migratory DCs are also able to activate CD4+ T cells by both direct antigen presentation as well as through antigen transfer to LN-resident DCs [33], whereas the latter cells only directly present antigens to CD4+ T cells. As a consequence, when antigen-pulsed DCs are adoptively transferred, antigen-carrying migratory DCs play a decisive role in CD4+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs. For CD8+ T cell proliferation, resident but not migratory DCs have previously been shown to be more efficient at cross-presentation of exogenous antigen [34]. However, studies have shown that adoptively transferred migratory DCs do in fact contact host CD8+ T cells in dLNs [35], and that these migratory DCs can cross-present [36]. Migratory submucosal DCs that translocate from the vaginal mucosa have also been shown to be the predominant antigen presenting cells (APCs) required for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell stimulation in the dLNs following intravaginal HSV-1 infection [37]. While the detailed mechanisms of antigen transfer from migratory to tissue-resident DCs, as well as the contributions of these two DC types on T cell proliferation still remain unclear [38], we do not exclude that our intravaginally administered DCs can transfer antigens to host tissue-resident DCs. In a separate experiment, the CFSE dilution values between adoptively transferred of total OTI splenocytes and pure OTI CD8+ T cells were found comparable each other, indicating that OT splenic APCs, which may be transferred to the recipient dLNs, did not play any role in antigen-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation in this study (Supplemental Figure 7). Therefore, we expect that the enhanced migratory capacity of Flt3-L-derived DCs promotes their translocation and antigen delivery across the mouse vaginal mucosa to the dLNs, and controls antigen-specific proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the dLNs. We have not formally demonstrated direct antigen presentation of intravaginally administered DCs to antigen-specific T cells in the dLNs in this study but plan to understand their antigen presentation in a future study.

DC chemotaxis (movement of cells responding to chemotactic stimulation) is strictly regulated by a myriad of chemotactic and non-chemotactic signals that include chemokines (e.g, CCL19 or CCL21) and non-chemokine factors such as bacterial products, DAMPs (danger-associated molecular patterns), complement proteins, or lipids acting individually or synergistically [39]. These myriad factors in complex tissue microenvironments, particularly mucosal tissue, have hindered deciphering the primary mechanism governing directional migration of DC to dLNs in vivo [40]. Evidence for directional guidance of DC chemotaxis has largely relied on the migratory trajectory of specifically stained DCs without measurement of in vivo distribution of chemotactic factors [41]. To better understand the mechanism underlying BMDC migration to dLNs, we measured our programmed BMDCs for CCR7 upregulation, which plays a critical role in DC migration along CCL21 chemotactic gradient in lymphatic vessels [42]. We found that CD11c+ FLPs showed thee-fold higher expression of CCR7 compared to CD11c+ GLPs (Figure 4). Therefore, CCR7 expression may enhance CD11c+ FLP translocation to the dLNs possibly along the CCL21 chemotactic gradient to the dLNs.

Cross-talk between non-DCs (e.g., neutrophils) and DCs is essential to positively respond to microbial infection [43] and we previously found that the presence of CD11c− cells (such as macrophages, monocytes, granulocytes, and lymphocytes) in GM-CSF-derived BMDC cultures enhanced OVA uptake in CD11c+ cells and positively influenced cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells in vitro [44]. To take advantage of cross-talk between CD11c+ and CD11c− cells, we utilized BMDCs without CD11c+ cell isolation. We made no attempt to understand why CD11c+ frequency was reduced for FLPs but not GLPs following adjuvant treatment. However, because we intravaginally administered the same number of adjuvant-treated GLPs and FLPs, we should have a smaller CD11c+ fraction of FLPs than that of GLPs administered to the vaginal mucosa. Consequently, we detected 8% CD11c+ FLPs out of the total donor CD45.1+ cells found in the host ILLNs (versus 14% of CD11c+ for GLPs) (Figure 2c). Therefore, more CD11c− FLPs than CD11c− GLPs could possibly be involved in BMDC translocation, OVA association, and T cell proliferation observed in this study. However, antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation in dLNs significantly decreased when CD11c+ cell-depleted mice were orally or intranasally immunized [45]. Also, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in dLNs were found to proliferate only after antigen presentation from CD11c+ DCs but not non-DCs following conventional immunization via the IVG route [46]. For these reasons, we expect that antigen presentation of CD11c− cells to T cells is unlikely in this study. Collectively, it is conceivable that compared to GLPs, more CD11c− FLPs and more activated CD11c+ FLPs synergistically impacted T cell proliferation in the dLNs by carrying, transferring, or presenting more antigens.

Adoptively transferred DCs that are programmed for the ability to cross-present protein antigens have great potential for eliciting both humoral and cellular protective immunity. In a mouse model of HSV-1 infection, 80% of virus-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes were found to be primarily derived by cross-presentation of viral proteins [47]. Also, multiple protein antigens in a single immunization induce robust B cell and T cell immunity [48]. As previously reported [49, 50], a high dose of OVA or MPLA induced an increasing trend of cross-presentation in vitro. However, we observed that FLPs induced the highest level of OVA-specific CD8+ T cell proliferation over all other programmed BMDCs in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, Flt3-L-based programming of BMDCs can be another potent strategy for inducing cross-presentation in the dLNs following DC-based immunization. In addition, SIINFEKL peptide-pulsed DCs have superior efficiency in stimulation of CD8+ T cell proliferation compared to cross-presentation of OVA protein-pulsed DCs at the same antigen dose [51]. In our in vivo setting, GLPs were unable to stimulate CD8+ T cell proliferation in the dLNs. In contrast, when Flt3-L-programmed BMDCs were pulsed with OVA protein or SIINFEKL peptide at the same dose by weight, OVA-pulsed FLPs stimulated CD8+ T cell proliferation at levels comparable to SIINFEKL-pulsed FLPs despite that the SIINFEKL peptide used for pulsing DCs was approximately 45 times greater than that peptide in the OVA protein by molar ratio (Supplemental Figure 7). These results indicate that when programmed with Flt3-L, DCs can simply be pulsed with pathogenic proteins without identification and preparation of specific antigenic peptide sequence for activating CD8+ T cells. However, as decreased or inverted CD4/CD8 T cell ratios can indicate impaired immune system in various diseases [52], control of the activation/proliferation ratio of those two T cell types may affect the cell-based immunotherapy efficacy. Since FLPs induced robust proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for all dLNs, we do not expect inverted CD4/CD8 T cell ratios to be a concern. However, in case abnormal ratios are induced by FLPs, we can possibly mix GLPs and FLPs to be administered so as to suppress overall CD8+ T cell proliferation thereby controlling (increasing) the ratio of CD4/CD8 T cells.

In DC-based vaccines, DCs work as living adjuvants by secreting various immunogenic signals such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and also function as live vehicle by directly presenting antigens to T cells and releasing them in a sustained manner [16, 53]. To further enhance this DC-based vaccine efficacy in systemic immunity, adoptively transferred DCs are required to migrate to dLNs [54] as well as to recruit host CD11c+ cells via secretion of immunogenic signals [55]. The vaginal canal is drained by the ILLN and IGLN in descending order from the RT [32], and this drainage is potent for eliciting adaptive immunity beyond local immune response [6, 7]. Therefore, our observations of DC translocation, T cell proliferation, and host CD11c+ cell recruitment to the dLNs suggest that our adoptively transferred DCs are self-sufficient for creating a host immune environment, in the absence of additional adjuvant, which can potentially boost systemic protective immunity [55].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Adoptive transfer of dendritic cells (DCs) is a potent cell-based immunotherapy.

Direct DC transfer to mucosal sites may offer new strategies for mucosal vaccines.

Priming the mucosal epithelium with chitosan facilitates DC transmigration.

Flt3-L-based programming enhances DC accumulation in draining lymph nodes (dLNs).

Programmed DCs induce antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation in dLNs.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant (K.W.) (HD075703).

Footnotes

Competing interests: All authors declare no competing interests except D.M. Koelle has grants with or is a consultant for Sanofi Pasteur, Immunomic Therapeutics, Curevo, MaxHealth, Admedus Immunotherapies, and Merck.

Ethical statement: All animal procedures in this study were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number, 4260–01).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE, Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Adults: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 68 (2019) 698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kozlowski PA, Aldovini A, Mucosal Vaccine Approaches for Prevention of HIV and SIV Transmission, Current immunology reviews, 15 (2019) 102–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Harrison A, HIV prevention and research considerations for women in sub-Saharan Africa: moving toward biobehavioral prevention strategies, African journal of reproductive health, 18 (2014) 17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kozlowski PA, Cu-Uvin S, Neutra MR, Flanigan TP, Comparison of the oral, rectal, and vaginal immunization routes for induction of antibodies in rectal and genital tract secretions of women, Infection and immunity, 65 (1997) 1387–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li Z, Zhang M, Zhou C, Zhao X, Iijima N, Frankel FR, Novel vaccination protocol with two live mucosal vectors elicits strong cell-mediated immunity in the vagina and protects against vaginal virus challenge, J Immunol, 180 (2008) 2504–2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pavot V, Rochereau N, Genin C, Verrier B, Paul S, New insights in mucosal vaccine development, Vaccine, 30 (2012) 142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marks E, Helgeby A, Andersson JO, Schon K, Lycke NY, CD4(+) T-cell immunity in the female genital tract is critically dependent on local mucosal immunization, Eur J Immunol, 41 (2011) 2642–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Neutra MR, Kozlowski PA, Mucosal vaccines: the promise and the challenge, Nat Rev Immunol, 6 (2006) 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lai SK, Wang YY, Hanes J, Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 61 (2009) 158–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Galindo-Rodriguez SA, Allemann E, Fessi H, Doelker E, Polymeric nanoparticles for oral delivery of drugs and vaccines: a critical evaluation of in vivo studies, Critical reviews in therapeutic drug carrier systems, 22 (2005) 419–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bhoopat L, Eiangleng L, Rugpao S, Frankel SS, Weissman D, Lekawanvijit S, Petchjom S, Thorner P, Bhoopat T, In vivo identification of Langerhans and related dendritic cells infected with HIV-1 subtype E in vaginal mucosa of asymptomatic patients, Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc, 14 (2001) 1263–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heit A, Busch DH, Wagner H, Schmitz F, Vaccine protocols for enhanced immunogenicity of exogenous antigens, Int J Med Microbiol, 298 (2008) 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Woodrow KA, Bennett KM, Lo DD, Mucosal vaccine design and delivery, Annual review of biomedical engineering, 14 (2012) 17–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Aline F, Brand D, Bout D, Pierre J, Fouquenet D, Verrier B, Dimier-Poisson I, Generation of specific Th1 and CD8+ T-cell responses by immunization with mouse CD8+ dendritic cells loaded with HIV-1 viral lysate or envelope glycoproteins, Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur, 9 (2007) 536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tel J, Aarntzen EH, Baba T, Schreibelt G, Schulte BM, Benitez-Ribas D, Boerman OC, Croockewit S, Oyen WJ, van Rossum M, Winkels G, Coulie PG, Punt CJ, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Natural human plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce antigen-specific T-cell responses in melanoma patients, Cancer research, 73 (2013) 1063–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Steinman RM, Bona C, Inaba K, Dendritic cells: important adjuvants during DNA vaccination, in, Landes Bioscience, Austin, TX, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Iwasaki A, Mucosal dendritic cells, Annual review of immunology, 25 (2007) 381–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hervouet C, Luci C, Bekri S, Juhel T, Bihl F, Braud VM, Czerkinsky C, Anjuere F, Antigen-bearing dendritic cells from the sublingual mucosa recirculate to distant systemic lymphoid organs to prime mucosal CD8 T cells, Mucosal immunology, 7 (2014) 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gao X, Wang S, Fan Y, Bai H, Yang J, Yang X, CD8+ DC, but Not CD8(−)DC, isolated from BCG-infected mice reduces pathological reactions induced by mycobacterial challenge infection, Plos One, 5 (2010) e9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mallipeddi R, Rohan LC, Nanoparticle-based vaginal drug delivery systems for HIV prevention, Expert opinion on drug delivery, 7 (2010) 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria, Nat Immunol, 2 (2001) 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ibata B, Parr EL, King NJ, Parr MB, Migration of foreign lymphocytes from the mouse vagina into the cervicovaginal mucosa and to the iliac lymph nodes, Biology of reproduction, 56 (1997) 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schon E, Harandi AM, Nordstrom I, Holmgren J, Eriksson K, Dendritic cell vaccination protects mice against lethality caused by genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection, Journal of reproductive immunology, 50 (2001) 87–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Amidi M, Mastrobattista E, Jiskoot W, Hennink WE, Chitosan-based delivery systems for protein therapeutics and antigens, Advanced drug delivery reviews, 62 (2010) 59–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Park J, Ramanathan R, Pham L, Woodrow KA, Chitosan enhances nanoparticle delivery from the reproductive tract to target draining lymphoid organs, Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine, 13 (2017) 2015–2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Xu Y, Zhan Y, Lew AM, Naik SH, Kershaw MH, Differential development of murine dendritic cells by GM-CSF versus Flt3 ligand has implications for inflammation and trafficking, J Immunol, 179 (2007) 7577–7584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Moon JJ, Chu HH, Hataye J, Pagan AJ, Pepper M, McLachlan JB, Zell T, Jenkins MK, Tracking epitope-specific T cells, Nat Protoc, 4 (2009) 565–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Park K, Mikulski Z, Seo GY, Andreyev AY, Marcovecchio P, Blatchley A, Kronenberg M, Hedrick CC, The transcription factor NR4A3 controls CD103+ dendritic cell migration, J Clin Invest, 126 (2016) 4603–4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Creusot RJ, Yaghoubi SS, Chang P, Chia J, Contag CH, Gambhir SS, Fathman CG, Lymphoid-tissue-specific homing of bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells, Blood, 113 (2009) 6638–6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Robson NC, Beacock-Sharp H, Donachie AM, Mowat AM, Dendritic cell maturation enhances CD8+ T-cell responses to exogenous antigen via a proteasome-independent mechanism of major histocompatibility complex class I loading, Immunology, 109 (2003) 374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Masten BJ, Olson GK, Kusewitt DF, Lipscomb MF, Flt3 ligand preferentially increases the number of functionally active myeloid dendritic cells in the lungs of mice, J Immunol, 172 (2004) 4077–4083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Iwasaki A, Antiviral immune responses in the genital tract: clues for vaccines, Nat Rev Immunol, 10 (2010) 699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Allenspach EJ, Lemos MP, Porrett PM, Turka LA, Laufer TM, Migratory and lymphoid-resident dendritic cells cooperate to efficiently prime naive CD4 T cells, Immunity, 29 (2008) 795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Shortman K, Heath WR, The CD8+ dendritic cell subset, Immunological reviews, 234 (2010) 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Stoll S, Delon J, Brotz TM, Germain RN, Dynamic imaging of T cell-dendritic cell interactions in lymph nodes, Science, 296 (2002) 1873–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bedoui S, Whitney PG, Waithman J, Eidsmo L, Wakim L, Caminschi I, Allan RS, Wojtasiak M, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Brooks AG, Heath WR, Cross-presentation of viral and self antigens by skin-derived CD103+ dendritic cells, Nat Immunol, 10 (2009) 488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lee HK, Zamora M, Linehan MM, Iijima N, Gonzalez D, Haberman A, Iwasaki A, Differential roles of migratory and resident DCs in T cell priming after mucosal or skin HSV-1 infection, J Exp Med, 206 (2009) 359–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Caminschi I, Maraskovsky E, Heath WR, Targeting Dendritic Cells in vivo for Cancer Therapy, Frontiers in immunology, 3 (2012) 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tiberio L, Del Prete A, Schioppa T, Sozio F, Bosisio D, Sozzani S, Chemokine and chemotactic signals in dendritic cell migration, Cellular & molecular immunology, 15 (2018) 346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Weber M, Hauschild R, Schwarz J, Moussion C, de Vries I, Legler DF, Luther SA, Bollenbach T, Sixt M, Interstitial dendritic cell guidance by haptotactic chemokine gradients, Science, 339 (2013) 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Boldajipour B, Mahabaleshwar H, Kardash E, Reichman-Fried M, Blaser H, Minina S, Wilson D, Xu Q, Raz E, Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration, Cell, 132 (2008) 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Perez CR, De Palma M, Engineering dendritic cell vaccines to improve cancer immunotherapy, Nature communications, 10 (2019) 5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bennouna S, Bliss SK, Curiel TJ, Denkers EY, Cross-talk in the innate immune system: neutrophils instruct recruitment and activation of dendritic cells during microbial infection, J Immunol, 171 (2003) 6052–6058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Frizzell H, Park J, Comandante Lou N, Woodrow KA, Role of heterogeneous cell population on modulation of dendritic cell phenotype and activation of CD8 T cells for use in cell-based immunotherapies, Cellular immunology, 311 (2017) 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fahlen-Yrlid L, Gustafsson T, Westlund J, Holmberg A, Strombeck A, Blomquist M, MacPherson GG, Holmgren J, Yrlid U, CD11c(high )dendritic cells are essential for activation of CD4+ T cells and generation of specific antibodies following mucosal immunization, J Immunol, 183 (2009) 5032–5041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hervouet C, Luci C, Rol N, Rousseau D, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Czerkinsky C, Anjuere F, Langerhans cells prime IL-17-producing T cells and dampen genital cytotoxic responses following mucosal immunization, J Immunol, 184 (2010) 4842–4851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].St Leger AJ, Peters B, Sidney J, Sette A, Hendricks RL, Defining the herpes simplex virus-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire in C57BL/6 mice, J Immunol, 186 (2011) 3927–3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang F, Lu YJ, Malley R, Multiple antigen-presenting system (MAPS) to induce comprehensive B- and T-cell immunity, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 110 (2013) 13564–13569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].den Haan JM, Bevan MJ, Constitutive versus activation-dependent cross-presentation of immune complexes by CD8(+) and CD8(−) dendritic cells in vivo, J Exp Med, 196 (2002) 817–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Boks MA, Ambrosini M, Bruijns SC, Kalay H, van Bloois L, Storm G, Garcia-Vallejo JJ, van Kooyk Y, MPLA incorporation into DC-targeting glycoliposomes favours anti-tumour T cell responses, J Control Release, 216 (2015) 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Met O, Buus S, Claesson MH, Peptide-loaded dendritic cells prime and activate MHC-class I-restricted T cells more efficiently than protein-loaded cross-presenting DC, Cellular immunology, 222 (2003) 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].McBride JA, Striker R, Imbalance in the game of T cells: What can the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio tell us about HIV and health?, PLoS pathogens, 13 (2017) e1006624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Schuurhuis DH, van Montfoort N, Ioan-Facsinay A, Jiawan R, Camps M, Nouta J, Melief CJ, Verbeek JS, Ossendorp F, Immune complex-loaded dendritic cells are superior to soluble immune complexes as antitumor vaccine, J Immunol, 176 (2006) 4573–4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Shang N, Figini M, Shangguan J, Wang B, Sun C, Pan L, Ma Q, Zhang Z, Dendritic cells based immunotherapy, American journal of cancer research, 7 (2017) 2091–2102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Steinman RM, Pope M, Exploiting dendritic cells to improve vaccine efficacy, J Clin Invest, 109 (2002) 1519–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.