Abstract

Purpose:

With the rapid spread of COVID-19 in New York City since early March 2020, innovative measures were needed for clinical pharmacy specialists to provide direct clinical care safely to cancer patients. Allocating the workforce was necessary to meet the surging needs of the inpatient services due to the COVID-19 outbreak, which had the potential to compromise outpatient services. We present here our approach of restructuring clinical pharmacy services and providing direct patient care in outpatient clinics during the pandemic.

Data sources:

We conducted a retrospective review of electronic clinical documentation involving clinical pharmacy specialist patient encounters in 9 outpatient clinics from March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020. The analysis of the clinical pharmacy specialist interventions and the impact of the interventions was descriptive.

Data summary:

As hospital services were modified to handle the surge due to COVID-19, select clinical pharmacy specialists were redeployed from the outpatient clinics or research blocks to COVID-19 inpatient teams. During these 3 months, clinical pharmacy specialists were involved in 2535 patient visits from 9 outpatient clinics and contributed a total of 4022 interventions, the majority of which utilized telemedicine. The interventions provided critical clinical pharmacy care during the pandemic and omitted 199 in-person visits for medical care.

Conclusion:

The swift transition to telemedicine allowed the provision of direct clinical pharmacy services to patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Clinical pharmacy, outpatient clinic, COVID-19

Introduction

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in China in December 2019 and has disseminated across the world since that time. In the United States (US), the New York City (NYC) area became the epicenter of the pandemic in March 2020. As of the time of writing, there had been more than 5.7 million confirmed cases in the U.S., with more than 230,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 23,000 deaths in NYC.1 Several studies suggest the outcome of COVID-19 is worse among patients with cancer, with a fatality rate of up to 20%.2–8 However, a recent study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) showed that patients receiving chemotherapy or with metastatic disease were not at a higher risk for hospitalization or developing severe respiratory illness from COVID-19.2 Also, another study showed that pediatric patients with cancer may not have a higher infection or morbidity rate than the general pediatric population.9 Because appropriate treatment and timely supportive care can extend the overall survival of patients with cancer, the availability of high-quality, evidence-based provision of care during the pandemic was crucial to prevent not only morbidity but also premature death.10 However, patients receiving cancer treatment in cities on the quarantine list or under stay-at-home orders, like NYC, struggled to travel to treatment sites and/or acquire essential medications.11 Additionally, the pandemic created barriers to patients’ enrollment and participation in oncology clinical trials due to protocol stipulations.

At the beginning of the pandemic, when medical resources were diverted to tackle the surge of COVID-19 patients in intensive care units (ICUs), hospitals (including MSK) took action by implementing prevention and control measures to protect staff and patients from infection.12,13 Aside from testing and tracing, some of these measures included limiting the number of in-person outpatient visits, increasing the volume of telemedicine visits and reducing the number of ancillary staff onsite. To accommodate the challenges of patients on clinical trials, sponsors and regulatory authorities eased inflexible rules to study assessments and study drug dispensing.14 Institutionally, virtual or phone outpatient consultations allowed the physicians, nurses, clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), and other clinicians to collect patient information, monitor symptoms and provide supportive care functions remotely, eventually reducing unplanned visits.15

At MSK, CPSs play an essential role in direct patient care. A CPS may become credentialed to allow for collaborative practice with the treating physician.16 A credentialed pharmacist, by New York State law, is approved to provide collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM), which includes changing the dose, frequency or route of therapies and ordering tests in collaboration with a licensed physician after written consent is obtained from the patient.16 The thirty-five clinical pharmacy specialists at MSK are board-certified in either oncology (BCOP), pharmacotherapy (BCPS), pediatrics (BCPPS), infectious disease (BCIDP), or geriatrics (BCGP), with some staff holding dual board certifications. Prior to the pandemic, the clinical pharmacy department at MSK covered 10 outpatient clinics, 15 inpatient teams encompassing 9 services, and an infectious disease antibiotic management program. Most CPSs are grouped within disease-state pods, within which, the CPS will rotate between an inpatient team, an outpatient clinic, and a research block, on a defined interval (typically every 1–3 months) (Table 1). Key clinical roles of CPSs in outpatient clinics encompass assessing patients and providing support and continuity of care using prescriptive authority. Like other providers, the CPSs document interventions and patient encounters in the electronic medical record by entering clinical notes that contain the recommended therapeutic plans for treatment and monitoring of drug therapy.

Table 1.

Allocation of clinical pharmacy resources.

| Area of CPS service | Baseline operations (n = 35 CPS) | COVID-19 response (n = 35 CPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Outpatient | 15 CPSa covering 10 outpatient clinics | 12 CPSa covering 9 outpatient clinics |

| Inpatient | 15 CPSa covering 9 inpatient teams | 15 CPSa,b covering 9 inpatient teams |

| 1 CPS covering Antibiotic Management Program | (5 inpatient services were converted to COVID services) | |

| 1 CPS covering Antibiotic Management Program | ||

| COVID-19 ICU teams | None | 6 CPS covering 3 newly created ICU teams (2 each) |

| COVID-19 non-ICU inpatient teams | None | 3 CPSb covering 3 inpatient COVID-19 teams (2 teams were not covered) |

| Research | 4 CPS | 1 CPS |

One CPS splits coverage between an inpatient team and an outpatient clinic.

One CPS split coverage on a COVID-19 inpatient service with a non-COVID-19 inpatient team.

During the surge of COVID-19 cases reported here, all clinicians were encouraged by the insitution’s leadership to conduct outpatient visits virtually from remote locations (home) to minimize the risk of virus transmission and provide cancer and supportive care treatment to the highest extent possible. Due to the urgency of the change from in-person to virtual visits, the percentage of outpatient virtual visits as compared to in-person, onsite visits and the telemedicine platform used for outpatient virtual visits varied throughout different outpatient clinics. Similar to other healthcare professionals (HCPs) on the front line of patient care, the workforce of clinical pharmacy specialists were affected by the crisis. We sought to describe the restructuring of MSK’s clinical pharmacy practice and the CPS interventions in the outpatient setting during the crisis.

Methods

Data collection for this analysis was conducted by the CPSs who engaged in outpatient clinical activities during the pandemic. Reports detailing electronic clinical documentation of in-person or virtual patient encounters and prescription orders from March 1, 2020 through May 31, 2020 were queried. A data collection tool was created for clinical interventions to be categorized according to patient encounters and activity. Furthermore, the impact of the interventions on in-person patient visits to MSK sites was tabulated. Prior to data collection, this project proposal was reviewed by the MSK Institutional Review Board (IRB) leadership and it was determined not constitute human subjects research and therefore, did not require IRB oversight. Statistical analysis was completed with the use of Microsoft Office 365® Excel ® (Redmond, WA) Descriptive statistics were used to describe the clinical interventions and their impact.

Results

Restructuring of the CPS service

In response to the rising number of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 and requiring hospital admission, our institution expanded ICU services from 2 teams to 5 teams and created 5 inpatient, non-ICU teams dedicated to patients with COVID-19 (4 adult teams and 1 pediatric team). In response, 6 CPSs were re-assigned to these ICU teams (2 CPS per ICU team) operating in a 7 days on and 7 days off schedule. These 6 CPSs were pulled from their current research blocks and outpatient clinics. The 5 non-ICU COVID-19 services were converted from existing inpatient services and therefore were covered by those CPSs already assigned to those disease teams. For the outpatient clinics to minimize exposure and risk of transmission, MSK quickly provided virtual desktop access, telemedicine options and other technology to the clinical staff to drastically reduce the need for onsite, face-to-face visits. This allowed those CPSs who remained in the outpatient setting to perform patient care activities remotely. Twelve CPSs continued to support 9 outpatient clinics during the pandemic as opposed to 15 supporting 10 services pre-COVID-19 (Table 1).

Outpatient CPS interventions

Between March 1, 2020 and May 3, 2020 there were 2535 pharmacy patient visits encompassing 9 clinic services and a total of 4022 interventions (Figure 1) occurred. Of these 2535 patient visits, 924 patients were enrolled in a clinical research trial and 58 patients were confirmed COVID-19 positive. Most of these patient visits were conducted via telemedicine (99%) while 15 visits continued in person (1%).

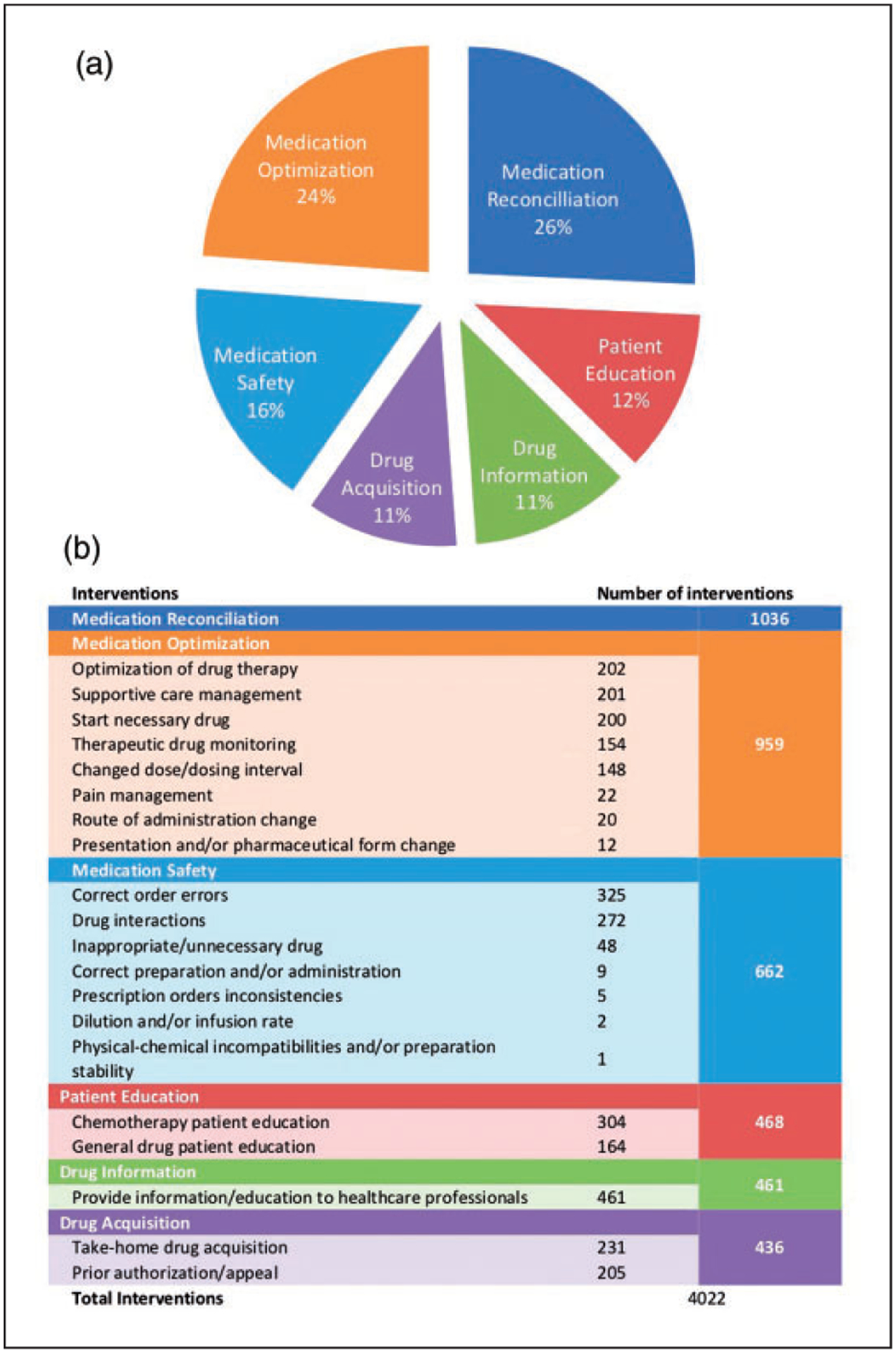

Figure 1.

Summary of Outpatient Clinical Interventions. (a). The pie chart shows the distribution of interventions in 6 different categories. (b). Number of interventions in each subcategory.

All interventions performed during the specified time period were categorized into 6 different groups of clinical interventions as shown in Figure 1. Medication reconciliation was the most common intervention and occurred in 40% of all patient visits and accounted for 26% of interventions during this period. Other common interventions performed included medication optimization (24%), providing education to health care professionals and answering drug information questions (11%), correcting medication order errors (8%), chemotherapy patient education (8%), and reviewing and identifying drug-drug interactions (7%).

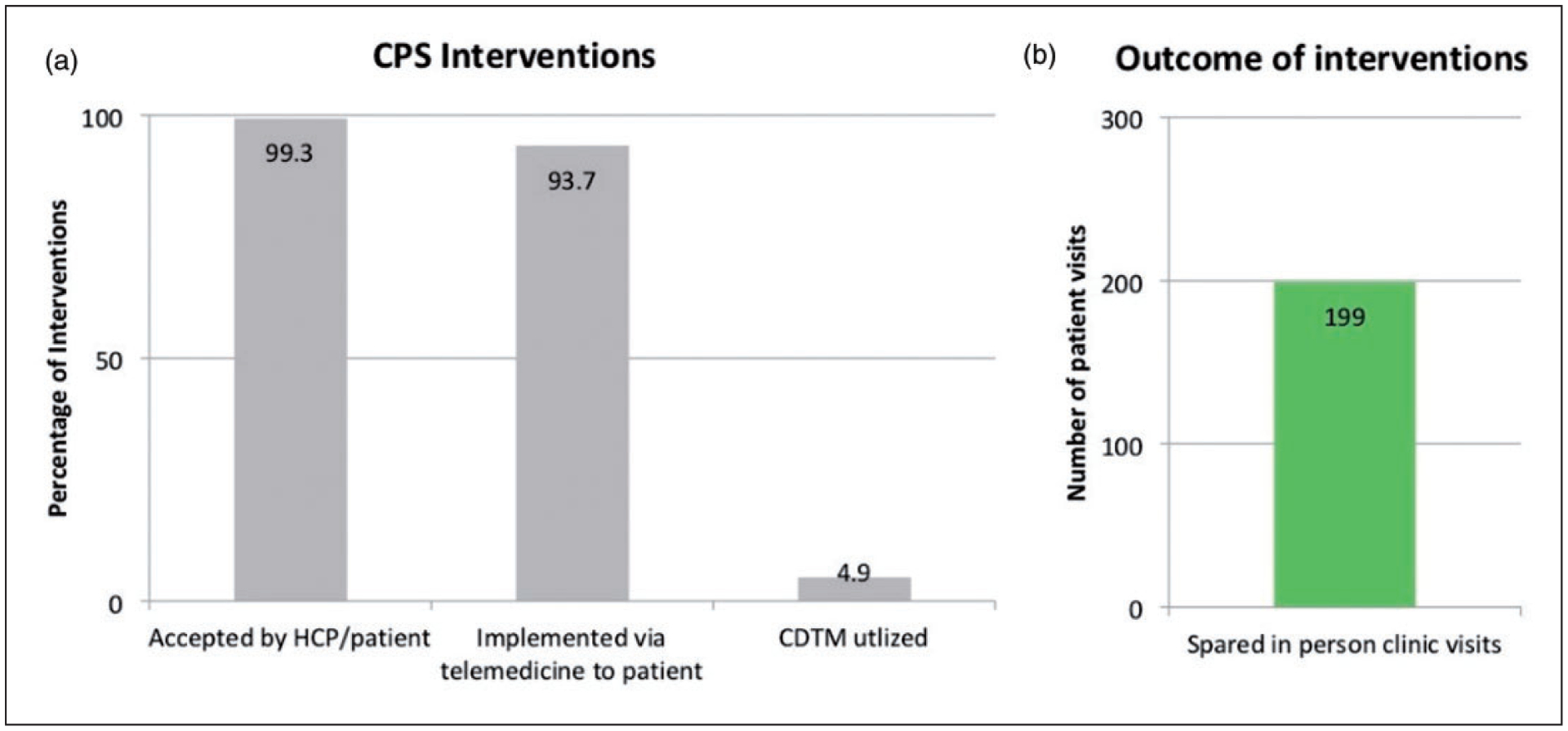

Figure 2 reviews COVID-19 related outcomes of interventions performed by a CPS during the specified period. Of the 4022 interventions, 3993 interventions (99%) were accepted by both the HCP and patient. The majority of interventions (3769, 94%) were communicated to the patient by the CPS using telemedicine including Cisco Jabber 12.6 (San Jose, CA), Doximity (San Francisco, CA), Zoom (San Jose, CA) or direct phone call, while 253 interventions (6%) were communicated to the patient through another health care team member. Additionally, 199 (5%) of these involved ordering prescriptions utilizing the CDTM agreement. Overall, using telehealth platforms, 265 of the CPSs interventions spared in-person patient visits for medical care for 199 patients (8%). Examples include: use of a long-acting hormonal therapy, arranging for drug shipment directly to the patient, administering peg-filgrastim on-body injector on the last day of a chemotherapy regimen, discontinuing unnecessary treatment, or switching intravenous to oral therapy (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The Impact of CPS Interventions on COVID-19 Related Outcomes. (a). The bar graph represents the percentages of intervention accepted by HCP/patient, implemented via telemedicine to the patient directly, and involved CDTM. (b). The bar graph shows the number of in-person visits spared by CPS interventions.

Table 2.

CPS interventions spared in-person visits.

| Classification of the interventions | Number (%) N = 265 | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Drug acquisition | 120 (45) | Arranged shipping oral investigational medications directly to the patient |

| Medication optimization | 65 (25) | Recommended to give peg-filgrastim on-body injector the same day as chemotherapy completed |

| Medication optimization | 37 (14) | Conducted required medication reconciliation via telemedicine and recommended alternative medications for drugs not permitted by the investigational protocol |

| Patient education | 23 (9) | Educated patient about the window of long-acting injections and reconciled injections with required laboratory test visit |

| Drug information | 14 (5) | Recommend switching monthly leuprolide injection to 3-month dose |

| Medication safety | 6 (2) | Stopped unnecessary weekly iron infusion |

Discussion

Cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the US.17 The COVID-19 outbreak had a profound effect on the management of patients with cancer and institutions responded and adjusted rapidly to provide a high level of clinical cancer care. As 6 CPSs were deployed to the critical care COVID-19 ICU teams, a realignment of outpatient clinic coverage was necessary. In our study, the restructuring within our CPS team demonstrated that the CPSs were able to provide virtual, outpatient clinical pharmacy services during the pandemic. In the height of the pandemic in NYC, for 3 months (March 1, 2020 to May 31, 2020), MSK CPSs were involved in 2535 outpatient patient visits and provided 4022 interventions across 9 outpatient clinics. Our roles remained to focus on optimization of drug therapy, medication safety, patient education, drug acquisition and drug information. Two-hundred and sixty-five of these interventions led to patient avoidance of 199 in-person visits, which potentially decreased the risk of exposure to COVID-19 in these patients. CPSs were an essential part of the patient care team during the pandemic. CPSs conducted primary roles such as medication reconciliation, patient education, and answering drug information questions. CPSs safeguarded order prescribing, drug preparation, administration, and drug-drug interactions. CPSs were actively involved in the decision-making process for optimizing cancer and supportive care treatment by contributing 965 interventions and prescribing in 199 patient visits under CDTM. Also, CPSs played a significant role in helping patients receive proper medications for cancer treatment, supportive management, and chronic health issues. Furthermore, it is also worth noting that the majority of interventions (93.7%) were communicated directly to patients through telemedicine after discussion with team HCPs and interventions were well-received.

The number of COVID-19 diagnoses may continue to rise for several months and even years.18 Protecting HCPs and patients with cancer is required until vaccination is widely available. At the time this manuscript was written, preventive measures remain in place at our institution and many of our outpatient clinic visits continue to be conducted by telemedicine. Since many patient encounters were via telemedicine, obtaining written CDTM consent was challenging. We hope that our experience can help the CPS teams of other institutions where COVID-19 continues to be a significant challenge to direct patient care. Potential, future regulations could further expand CPS practice, such as allowing for reimbursement for telemedicine visits led by a CPS in conjunction with a physician, removing the state requirement of patient written consent for CDTM, and allowing authorized CPSs to substitute another drug within the same therapeutic class if the ordered drug is unavailable or not covered by the patients insurance. All of these directives would alleviate the workload from other HCPs as well as expand pharmacy practice in line with existing privileges.

There were certain limitations associated with this study. It was a retrospective analysis at a single site and the interpretations of the impact and outcome of each intervention were evaluated by individual CPSs. As a result, individual variability and confirmation bias were inevitable among different CPSs. Second, it is challenging to compare the overall efficacy of outpatient pharmacy service prior to and during the pandemic as it is confounded by many other factors from difference services, patients, and clinicians in this once-in-a century crisis. Furthermore, the platform and technical support for telemedicine visits was not standardized in the early weeks of pandemic and they might not be fully available at other institutions, which limits the generalizability.

Conclusions

Providing clinical pharmacy services to adult and pediatric outpatient clinics during the pandemic was feasible and effective with redeployed staff and limited onsite work. Telemedicine, virtual desktop access and prescribing privileges allowed for the transition to remote patient care for our CPS team, but we still face challenges in delivering direct patient care in the COVID-19 era.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: DL attended advisory board of Pfizer and Heron Therapeutics. MB received honorarium from Pharmacy Times Office of Continuing Professional Education. LB attended advisory board of Pfizer.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus (COVID-19), www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html (accessed 2 September 2020).

- 2.Robilotti EV, Babady NE, Mead PA, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med 2020; 26: 1218–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyashita H, Mikami T, Chopra N, et al. Do patients with cancer have a poorer prognosis of COVID-19? An experience in New York city. Ann Oncol 2020; 31: 1088–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York hospital system. Cancer Discov 2020; 10: 935–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee LY, Cazier J-B, Angelis V, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1919–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Wang J and He J. Active and effective measures for the care of patients with cancer during the COVID-19 spread in China. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 631–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dai M, Liu D and Liu M. Patients with cancer appear more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2: a multicenter study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Cancer Discov 2020; 10: 783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulad F, Kamboj M, Bouvier N, et al. COVID-19 in children with cancer in New York city. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 1459–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The lancet O Safeguarding cancer care in a post-COVID-19 world. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The lancet O COVID-19: global consequences for oncology. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pushpam D, Bakhshi S and Agarwala S. Chemotherapy adaptations in a referral tertiary care center in India for ongoing therapy of pediatric patients with solid tumors during COVID19 pandemic and lockdown. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2020; 67: e28428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burki TK. Cancer care in the time of COVID-19. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food and Drug Administration: FDA guidance on conduct of clinical trials of medical products during COVID-19 pandemic: guidance for industry, investigators, and institutional review boards. www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/fda-guidance-conduct-clinical-trials-medical-products-during-covid-19-public-health-emergency (2020, accessed 2 September 2020).

- 15.Cinar P, Cox J, Kamal A, et al. Oncology care delivery in the COVID-19 pandemic: an opportunity to study innovations and outcomes. JCO Oncol Pract 2020; 16: 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The New York State Senate: Education Law, 6801-A, Collaborative drug therapy management demonstration program, www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/EDN/6801-A (2020, accessed 2 September 2020).

- 17.Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA A Cancer J Clin 2020; 70: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 2020; 368: 860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]