Juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) is a systemic vasculopathy with weakness and rash, frequently exhibiting a chronic/polycyclic course, and treated with broad immunosuppression. An interferon (IFN) signature correlates with disease activity.[1] Interferonopathies have been successfully targeted by janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors.[2, 3] We report the first comprehensive prospective evaluation of JAK inhibition (baricitinib) in JDM.

Four patients (5.8–20.7 years old) with chronically active JDM (≥3/6 core set measures)[4] who had failed 3–6 immunomodulatory medications, were enrolled on compassionate use study NCT01724580 (supplementary methods, supplementary table 1). Biologics other than IVIG were washed out and other medications continued.

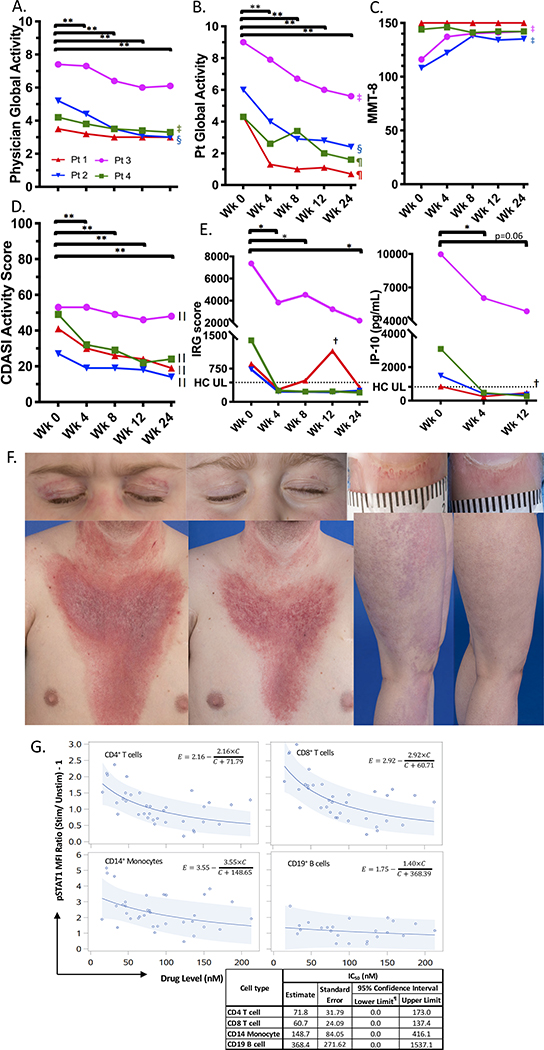

Subjects were assessed before, and 4, 8, 12, and 24 weeks after starting baricitinib (4–8 mg/day divided BID) dosed by weight and renal function.[3] Significant improvement was noted by week 4 in Physician Global Activity, Patient Global Activity, and Extramuscular Global Activity, and Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index (figure 1, supplementary table 2). Two patients with baseline weakness improved by week 4 (ACR/EULAR Myositis Response Criteria) and showed clinically relevant improvement in Manual Muscle Testing-8 by week 8, confirmed by blinded MRI assessment (supplementary figures 1&2). There was no significant change in muscle enzymes (supplementary table 3), though some had variable elevations with stable/improved strength. Daily corticosteroids were decreased (0.28 to 0.18 mg/kg/day); other immunosuppressive medications were decreased/discontinued (supplementary table 1). There were no flares/worsening requiring increased immunosuppression. There was no notable change in calcinosis (n=2).

Figure 1.

Change in disease activity and pharmacodynamic markers on baricitinib treatment.

*P <0.05; **P <0.01; ‡Clinically relevant minimal improvement; §Clinically relevant moderate improvement; ¶Clinically relevant major improvement; ||Clinical significant improvement in three by week 4 and in the fourth (Patient 3) by week 12.†: This patient had a suspected viral infection around the week 12 visit. ¶: Calculated 95% lower limits which were negative are reset to 0 as drug levels are never negative. The dotted line represents the highest value from healthy controls.

A-D. Multiple clinical assessments are shown at baseline (week 0), weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24 with the range of assessment values on the Y-axis. Each color represents a different patient. Clinically relevant improvement in core set measures was based on relative percent change from baseline or a 5 point decrease on CDASI at 24 weeks. P-values were calculated based on linear mixed model analysis of the repeated measures data. At 24 weeks, p-values are FDR adjusted since the 24 week timepoint compared to the baseline is the main analysis interest. At other timepoints, p-values are not adjusted for multiplicity. E: Left panel: Twenty eight-gene IRG (interferon-regulated gene) score shown at baseline (Wk 0) and weeks 4, 8, 12, and 24. Right panel: Serum IP-10 levels at baseline (Wk 0), Wk 4, and Wk 12. Log2 values were analyzed via 2-tailed paired t-test without correction versus baseline. F: Example images of each of the four patients showing the same part of the body at baseline (left) and after 24 weeks (right) for heliotrope and malar rash, dilated and tortuous nailfold capillaries on right second finger, V-sign rash with significant erythema and scale, and violaceous erythema on the lateral thigh and proximal leg. G: Scatter plots with model curves for pSTAT1 by cell type are shown with MFI ratio (IFN-α stimulated divided by un-stimulated) minus 1 versus the peripheral blood drug level. The solid line and light blue band show best-fit curves with 95% predictive intervals, respectively. The table shows IC50 values by cell type calculated based on modeling (estimated) with standard error, and 95% confidence intervals.

Wk: week; PGA: Physician Global Activity; Pt: Patient/ Parent; MMT-8: Manual Muscle Testing 8; CDASI: Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Area and Severity Index; IRG: interferon-regulated gene; HC, healthy controls; UL, Upper limit; MFI: median fluorescence intensity; pSTAT: STAT phosphorylation; Stim: Stimulated; Unstim: Unstimulated.

Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis revealed generally shorter half-life in the lower weight category, and longer half-life with lower renal function (supplementary table 4). Dosing (mean 7.25 mg/day) resulted in ~50% higher exposure (AUC 0–24, ss: 1988 hr*nM) compared to adult rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (4 mg QD, 1304 hr*nM, data on file, Eli Lilly and Company). Dosing is likely justified by IFN targeting[3] distinct from RA targets, and increased clearance, with dose-normalized PK parameter estimates similar to pediatric interferonopathies.[3]

No serious adverse events (AEs) occurred and no subject discontinued baricitinib. There were 43 AEs by week 24 (supplementary table 5), with infection (upper respiratory) the most common as expected.[2, 5] BK virus was monitored due to concerns for opportunistic infection.[2] BK virus was detectable at baseline in one patient, with viremia resolving and viruria decreasing by week 24, contemporaneous with tacrolimus discontinuation. Another patient developed BK viruria. Other expected AEs included hematologic abnormalities and elevated creatine kinase (CK)[5] (supplementary tables 3&5).

STAT phosphorylation (pSTAT) assays were timed with PK samples to assess baricitinib concentrations required for 50% inhibition of stimulated pSTAT (IC50). IFN-markers (interferon-regulated gene score, IP-10/CXCL10) decreased in all, with three reducing to normal by week 4 (figure 1E, supplementary table 2). IFN-α stimulated pSTAT1 and IL-2 stimulated pSTAT5 IC50s were lowest in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, while IL-10-stimulated pSTAT3 IC50s were lowest in CD4+ T and CD19+ B cells (figure 1G, supplementary figure 3).

These results indicate baricitinib was clinically beneficial and safe in refractory patients, extending previous case reports.[6] The correlation of dose-dependent decrease in pharmacodynamic measures and clinical improvement provide proof-of-concept for JAK inhibition in JDM. One patient had IFN-marker elevation with suspected viral infection, which is reassuring when balancing pathogenic and physiologic IFN signaling with JAK inhibition. Infection monitoring including BK virus is recommended. As transaminitis and elevated CK (muscle enzymes) have been reported with baricitinib,[2, 5] clinical assessment of strength and/or other assessments (i.e. MRI) is important when using baricitinib for myositis. While increases in the number of patients and duration of treatment are needed, benefit in this open-label study is strongly supported by objective measures including blinded MRI scoring and photography. Baricitinib is an exciting therapeutic option that merits further study in JDM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Michaele R. Smith, M Ed, PT, Galen Joe, MD, Meryl Waldman, MD, Adam Schiffenbauer, MD, and Beth Solomon, MS, CCC for their invaluable consultations and Ira N. Targoff, M.D. for assessment of autoantibodies. We thank Drs. Sarfaraz A. Hasni and Andrew L. Mammen for their critical reading of the manuscript. Some data were presented at GCOM and ACR 2019. We would also like to thank all our patients and their families for their participation.

Funding This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAMS including the Translational Immunology Section, NIEHS (ZIAES101081), and CC. Eli Lilly and Company provided baricitinib, pharmacokinetic and BK virus testing, and support through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement. Eli Lilly and Company is the sponsor of this expanded access program.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Image consent obtained for facial images.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design or conduct or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Ethics Approval All subjects were enrolled in expanded access program and natural history study approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board, and all patients/parents provided informed consent as well as photography consent.

Data sharing statement All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References.

- 1.Wienke J, Deakin CT, Wedderburn LR, et al. Systemic and Tissue Inflammation in Juvenile Dermatomyositis: From Pathogenesis to the Quest for Monitoring Tools. Front Immunol 2018;9:2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez GAM, Reinhardt A, Ramsey S, et al. JAK1/2 inhibition with baricitinib in the treatment of autoinflammatory interferonopathies. J Clin Invest 2018;128:3041–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim H, Brooks KM, Tang CC, et al. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Proposed Dosing of the Oral JAK1 and JAK2 Inhibitor Baricitinib in Pediatric and Young Adult CANDLE and SAVI Patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018;104:364–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rider LG, Aggarwal R, Pistorio A, et al. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Criteria for Minimal, Moderate, and Major Clinical Response in Juvenile Dermatomyositis: An International Myositis Assessment and Clinical Studies Group/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Genovese MC, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety Profile of Baricitinib in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis with over 2 Years Median Time in Treatment. J Rheumatol 2019;46:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladislau L, Suarez-Calvet X, Toquet S, et al. JAK inhibitor improves type I interferon induced damage: proof of concept in dermatomyositis. Brain 2018;141:1609–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.