Abstract

The role of transforming growth factor β TGFβ/activin signaling in wound repair and regeneration is highly conserved in the animal kingdom. Various studies have shown that TGF-β/activin signaling can either promote or inhibit different aspects of the regeneration process (i.e., proliferation, differentiation, and re-epithelialization). It has been demonstrated in several biological systems that some of the different cellular responses promoted by TGFβ/activin signaling depend on the activation of Smad-dependent or Smad-independent signal transduction pathways. In the context of regeneration and wound healing, it has been shown that the type of R-Smad stimulated determines the different effects that can be obtained. However, neither the possible roles of Smad-independent pathways nor the interaction of the TGFβ/activin pathway with other complex signaling networks involved in the regenerative process has been studied extensively. Here, we review the important aspects concerning the TGFβ/activin signaling pathway in the regeneration process. We discuss data regarding the role of TGF-β/activin in the most common animal regenerative models to demonstrate how this signaling promotes or inhibits regeneration, depending on the cellular context.

Keywords: Appendage regeneration, TGFβ/activin signaling, Wound repair, Scarless repair, Fibrosis

Introduction

Animal regeneration is the identical reconstitution of a structure, tissue, or organ that has been injured (Carlson 2007). Regeneration is essentially a primitive condition exhibited by several invertebrates that is linked to their specific lifestyles and ways of interacting with the environment. In fact, regeneration constitutes a form of asexual reproduction for many of these invertebrates (Ferretti and Géraudie 1997). Interestingly, some species of vertebrates, such as zebrafish and axolotls, have conserved the ability to regenerate complex structures; therefore, they have been used as models to identify crucial regulators of regeneration in animals that are evolutionarily closer to humans. One of these regulators is transforming growth factor β (TGFβ)/activin signaling, a highly conserved pathway in the animal kingdom that participates in several physiological processes, including regeneration (Bielefeld et al. 2013). The TGFβ/activin system is mainly constituted by several extracellular factors that bind to specific receptor complexes that activate signaling pathways, resulting in the regulation of target genes that play important roles in cell physiology. Here, we review and discuss the available data regarding the role of TGFβ/activin signaling in different regenerative models to demonstrate that the TGFβ/activin system can either promote or inhibit the regeneration process, depending on the cellular context, and how different ligands can promote antagonistic responses, despite activating the same intracellular pathway.

The TGFβ/activin signaling pathway

The TGFβ/activin signaling pathway is triggered by several diffusible factors of the TGFβ superfamily. Based on the similarity of its sequence, the TGFβ superfamily is grouped into the TGFβ, activin/inhibin and bone morphogenetic protein/growth differentiation factor (BMP/GDF) subfamilies (Massague 1998; Santibanez et al. 2011). The TGFβ subfamily comprises three isoforms in mammals, TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3, and two TGFβ ligands in Xenopus, xTGFβ2 and TGFβ5, whereas the activin subfamily includes activins A, B, AB, C, and E (Woodruff 1998). TGFβ is a homodimer, while activins can be homo or heterodimers constituted by two β subunits. Four of these activin β subunits have been identified: βA, βB, βC, and βE. The subunits that constitute the dimer dictate the type of activin that is generated; for example, activin A is formed by two βA subunits, activin B is constituted by two βB subunits, and activin AB is formed by one βA subunit and one βB subunit (Pangas and Woodruff 2000; Poniatowski et al. 2015). Activins C and E do not seem to signal through activin receptors but rather act as negative regulators of activin A activity by forming βA-βC or βA-βE heterodimers (Gold et al. 2009; Namwanje and Brown 2016).

Members of the TGFβ superfamily signal through two types of serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase transmembrane receptors, known as type I and type II receptors. Interaction of the ligand with the receptors forms an oligomeric complex consisting of two type I receptors, two type II receptors, and the ligand (Fig. 1) (Mu et al. 2012). Once this oligomeric complex is formed, type I receptors are activated by phosphorylation in their GS domain, an intracellular region rich in glycine and serine, by the constitutive serine/threonine kinase type II receptor (Lutz and Knaus 2002). The specific terms employed for type I and II receptors of the TGFβ subfamily members are TβRI or activin-like kinase 5 (ALK5) and TβRII, respectively. However, it has been reported that TGFβ ligands can also bind to the type I receptor ALK1 in endothelial cells (Goumans et al. 2002) and chondrocytes (Finnson et al. 2008, 2010). The typical type I receptor for activins is ActRIB or ALK4, although ALK7 can also interact with certain members of the activin subfamily. The type II receptors for activins are ActRII and ActRIIB, which also bind other related ligands, such as nodal and lefty, forming a complex with ActRIB (Table 1) (Feng and Derynck 2005).

Fig. 1.

Canonical and non-canonical TGFβ pathway. (1, 2) In the presence of ligands, two type I receptors (TβRI) and two type two receptors (TβRII) form the receptor complex. (3) This leads to the activation of TβRI by phosphorylation in their GS domain or in tyrosine (tyr) residues. The coreceptor betaglycan shows high binding affinity for TGFβ isoforms and presents ligands to TβRII. Endoglin is another coreceptor involved in regulation of TGFβ response. (4I) If phosphorylation occurs in the GS domain, the canonical pathway is induced. This consist of activation of the R-Smads Smad2 or Smad3, which form a complex with the co-Smad Smad4, resulting in its internalization to the cell nucleus and its interaction with DNA and other transcriptional comodulators. (4II) The Phosphorylation of tyr residues in TβRI or TβRII results in the activation of noncanonical pathways, e.g., c-Src phosphorylates the tyr residues of TβRII, leading to recruitment and formation of Shc and the Gbr2 complex that activates p38. Activation of TβRI on tyr residues drives ERK activation mediated by Shc. Alternatively, TAK1 is activated by TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination, promoting the activation of the ERK or p38 pathway

Table 1.

Receptors and Smads mediating the canonical pathway induced by TGFβ and activin ligands

Sources: Heldin and Moustakas (2012), Finnson et al. (2010), López-Casillas. et al. (1993), Liu et al. (2002)

| Ligand | Type II receptor | Type I receptor | Co-receptor | R-Smad | Co-Smad | I-Smad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ1 | TβRII | TβRI/ALK5 |

Smad2 Smad3 |

Smad4 | Smad7 | |

| TGFβ1 | TβRII | ALK1 | Endoglin |

Smad1 Smad5 |

Smad4 | |

| TGFβ2 | TβRII | TβRI/ALK5 | TβRIII/beta-glycan |

Smad2 Smad3 |

Smad4 | |

| TGFβ3 | TβRII | TβRI/ALK5 |

Smad2 Smad3 |

Smad4 | ||

| Activin A |

ActRII ActRIIB |

ActRIB/ALK4 |

Smad2 Smad3 |

Smad4 | Smad7 | |

| Activin B |

ActRII ActRIIB |

ActRIB/ALK4 |

Smad2 Samd3 |

Smad4 | Smad7 | |

| Activin AB |

ActRII ActRIIB |

ActRIB/ALK4 |

Smad2 Smad3 |

Smad4 | Smad7 |

Betaglycan and endoglin glycoproteins are two cell surface coreceptors that increase the binding affinity of TGFβ isoforms to the type II receptor. Betaglycan is also known as the TGFβ type III receptor, and its role as a supporter of ligand recognition is more evident for TGFβ2, since this isoform shows low affinity to TβRII (Bilandzic and Stenvers 2011; López-Casillas et al. 1993). Endoglin is a disulfide-linked dimer glycoprotein initially identified as a coreceptor for TGFβ1 (Kim et al. 2019). In contrast, activins do not require coreceptors to increase their activity.

Once type I receptors are activated, they phosphorylate in the carboxy-terminal region, a coupled protein termed receptor-activated Smad (R-Smad), causing its dissociation from the type I receptor and the formation of a new complex with another Smad, Co-Smad (Fig. 1). There are two R-Smads that transduce signals of TGFβs and activins, Smad2 and Smad3, while Smad4 is a unique Co-Smad found in most metazoans (Table 1). The R-Smad/Co-Smad complex is then translocated into the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors, coactivators or corepressors to regulate the transcription of several target genes (Fig. 1) (Heldin and Moustakas 2012).

In particular, the interaction of TGFβ1 with the TGFβRII-ALK1 complex in endothelial cells and chondrocytes results in Smad1 or Smad5 activation, although these Smads are primarily activated by BMP receptors (Finnson et al. 2010; Goumans et al. 2002). In chondrocytes, endoglin enhances Smad 1/5 phosphorylation induced by TGFβ1 through TGFβRII-ALK1 and inhibits transcriptional activity driven by Smad2 and Smad3 (Finnson et al. 2010), suggesting that endoglin could be involved in the activation of BMP R-Smads through TGFβ signaling.

On the other hand, inhibitory Smads (I-Smads) are a third group of Smads present in animal cells. They downregulate TGFβ/activin signaling by suppressing the Smad-dependent pathway of the TGFβ superfamily. Two I-Smads have been recognized in vertebrates: Smad6 and Smad7. Smad6 preferentially inhibits BMP signaling, while Smad7 regulates the activities of TGFβs and activins (Table 1). Smad7 competes with Smad2/3 for TβRI interaction (Hanyu et al. 2001; Heldin and Moustakas 2012; Santibanez et al. 2011) and recruits the ubiquitin ligases Smurf-1 and Smurf-2, which lead to proteasomal degradation of TβRI (Ebisawa et al. 2001). Smad7 is also a direct target gene of the TGFβ/activin signal; thus, both pathways are self-regulated by this mechanism (Ebisawa et al. 2001; Kavsak et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2002).

Although TGFβ superfamily signaling is conceptually relatively simple, the cellular responses that it regulates are very diverse due to the interaction of Smads with different transcription factors (Feng and Derynck 2005). In addition to the Smad pathway, TGFβ superfamily members activate Smad-independent signaling pathways as well, depending on the tyrosine‒kinase activity of TGFβ receptors. For example, phosphorylation of TβRII by the proto-oncogene src (c-src) results in the recruitment of both adaptor proteins, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2) and src homology and collagen (Shc), leading to activation of P38 mitogen-activated protein (p38) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, phosphorylation of TβRI at tyrosine residues, either by autophosphorylation or mediated by TβRII, induces its association with Shc and subsequent activation of extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) signaling (Fig. 1) (Galliher and Schiemann 2007; Lee et al. 2007). In addition, transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), a MAP kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK), mediates the activation of several TGFβ noncanonical pathways, including ERK and p38. Stimulation of TAK 1 depends on the interaction of TβR1 with TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), a ubiquitin ligase 3 (E3). This interaction results in the auto-ubiquitination of TRAF6 and the activation of TAK1 (Fig. 1) (Sorrentino et al. 2008). Furthermore, TAK1 activation by TGF-β stimulates the survival of osteoclasts through nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) (Gingery et al. 2008). The activation of Smad-dependent and -independent pathways, as well as the interaction of Smads with other transcription comodulators, extends the biological response of TGFβ superfamily members, resulting in diverse roles of this signaling pathway during the development and regeneration of metazoan organisms (Derynck and Zhang 2003; Zhang 2017).

The promoting role of TGFβ signaling on regeneration

Mammal skin: the antagonistic effects of TGFβ1 and TGFβ3

The role of TGFβ subfamily members during wound healing of mammalian skin has been studied by the exogenous administration of the three TGFβ isoforms or by the blockade of TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 endogenous activity with neutralizing antibodies on incisional wounds inflicted on the backs of adult rats. Interestingly, the response obtained following treatment with TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 is distinct from that observed for TGFβ3 administration. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 increased fibronectin and collagen synthesis, while TGFβ3 decreased the deposition of these extracellular matrix (ECM) components compared to the control group. Similarly, administration of TGFβ1- or TGFβ2-neutralizing antibodies decreases fibronectin, collagen I and collagen III deposition, improving neodermal architecture (Shah et al. 1995).

On the other hand, full-thickness incisional wounds in the anterior thigh of humans lead to fibrotic scar formation that is characterized by high levels of TGFβ1 and low levels of TGFβ3, decorin and fibromodulin, which are members of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) and inhibit TGFβ1 activity. In contrast, superficial wounds healed with minimal scarring exhibited low levels of TGFβ1 but high levels of TGFβ3 and SLRPs. This correlation seems to be attributed to a clonal topographic specialization of fibroblasts that differentially reside in the papillary or reticular dermis and that synthetize different components of the ECM (Honardoust et al. 2012). In this regard, it has been hypothesized that ECM components secreted by papillary fibroblasts protect against the fibrotic effects of TGFβ1 (Janson et al. 2014). These findings are in agreement with Guerrero-Juarez et al., where through single-cell transcriptome analysis, it was found that large murine wounds contain an upper dermal fibroblast subpopulation that expresses low levels of Tgfbr2 and Tgfbr3 (betaglycan) receptors and a lower dermal fibroblast subpopulation that expresses high levels of these receptors, as well as Pdgfra (another fibrosis driver) (Guerrero-Juarez et al. 2019), indicating that regulation of wound repair depends not only on ligands but also on receptors. More studies are needed to determine the regulation and role of TGFβ/activin signaling in each fibroblast subpopulation during skin wound repair.

Unlike adult wounds, incisional skin wounds inflicted during early gestation in mammalian fetuses heal without scar formation (Bullard et al. 2003; Whitby and Ferguson 1991). This characteristic could be partially attributed to differences in the expression levels of several components of the TGFβ signaling pathway between adult and fetal skin. In comparison to adult tissues, fetal skin expresses higher protein content of all three TGFβ isoforms. The ratio of TGFβ1 is much greater than that of TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 in adult skin, while in fetal skin, levels of TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 are higher (Walraven et al. 2015). In addition, some direct target genes of TGFβ signaling, such as TGFβ-induced protein (TGFβi), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), are upregulated in adult skin. This increased expression appears to be independent of the Smad2/3 pathway, since lower levels of the phosphorylated forms of Smad2 and Smad3 (pSmad2/pSmad3) are found in the epidermis and dermis of adult skin compared to fetal skin (Walraven et al. 2015). Although there is a differential response in fetal and adult skin to damage (regenerative vs. scarring), when fetal fibroblasts are isolated, cultivated, and stimulated with TGFβ1, they acquire a fibrotic phenotype characterized by the expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), CTGF, PAI-1, TGFβi, fibronectin extra domain A (FnEDA), and TGFβ1. These data indicate that fetal fibroblasts are susceptible to fibrotic stimuli by TGFβ1 (Walraven et al. 2017).

Despite the differential role of TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 during wound repair, it has been reported that TGFβ3 promotes upregulation of profibrotic factors (α-SMA and collagen I) in dermal fibroblasts isolated from Foxn-1-deficient nude mice, characterized by nonscarring skin wound repair. Furthermore, these cells demonstrated higher Tgfβ3 expression levels and were more sensitive to the TGFβ3 response than dermal fibroblasts isolated from Balb/c mice (Bukowska et al. 2018). This indicates that the scarless wound healing observed in Foxn-1-deficient nude mice might be independent of TGFβ subfamily stimulation and that TGFβ3 also acts as a profibrotic factor under certain unspecified and unknown circumstances. This argument may also explain why the use of TGFβ3 as an anti-scarring agent in a phase III clinical trial exhibited no significant effect compared to placebo (Pharmaletter 2011).

Structural conformation of the TGFβ isoforms induces differential biological responses

Seemingly, the differential responses reported in vivo to TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 depend on the interactions in which they might engage with other extracellular molecules; this hypothesis derives from structural studies conducted on TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 isoforms. The three-dimensional (3D) structure of TGFβ isoforms consists of two monomers bonded by means of a disulfide link. A practical representation of the system is the hand/foot analogy: one monomer is visualized as an extended hand, whose “palm” fits into the “heel” of the other monomer. The palm consists of a structurally stable α-helix 3 that comes into contact with the heel of the other monomer, resulting in a closed conformation that predominates in the TGFβ1 structure (Hinck et al. 1996; Huang et al. 2014). An open conformation has also been characterized and consists of a 101-degree rotation of one monomer with respect to another, which predominates in the TGFβ3 structure (Bocharov et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2014). This rotation is due to variations in the amino acid sequence in α-helix 3, which may cause a steric overlap between α-helix 3 and the heel of the opposing monomer. Evidence conferring the influence of α-helix 3 in the predominance on one of the two conformations derives from chimeric constructs where the α-helix 3 of TGFβ1 is exchanged for the α-helix 3 of TGFβ3 (construction denominated TGFβ 131), and the α-helix 3 of TGFβ3 is exchanged for the α-helix of TGFβ1 (construction denominated TGFβ 313). Interestingly, administration of TGFβ3 and TGFβ131, which demonstrate a predominantly open conformation, regulated fibroblast migration in 3D collagen matrices, in contrast to the null effect of TGFβ1 and TGFβ313 on this process, indicating that the 3D conformation influences the biological activity of each TGFβ isoform (Huang et al. 2014). It has been reported that TGFβ3 possesses a slightly greater affinity for TβRI than TGFβ1 due to their slower dissociation rate (Radaev et al. 2010). This could influence generation of the differential biological responses by the TGFβ isoforms. To elucidate whether the type of conformation is related to the affinity of the isoforms to their receptors, Huang et al. constructed a TGFβ3 variant with an α-helix 3 with only four substitutions of amino acids. Three of them contribute to generating the predominance of the closed conformation without affecting the α-helix amino acids that interact with the type I receptor. As expected, this chimera acquired a closed conformation, but its kinetics and affinity to recruit TβRI were the same as those of TGFβ3, indicating that conformation is not responsible for the different affinities of each isoform with its receptor. Nevertheless, it has been proposed that the differential effects among TGFβ isoforms are regulated by their interaction with other TGFβ-binding proteins, such as betaglycan, α2-macroglobulin, or decorin, whose affinity might be variable according to the open or closed conformations (Huang et al. 2014). This is a very feasible hypothesis that could explain the intriguing question concerning how diverse isoforms generate different responses, even though they bind to the same receptor complex or activate the same intracellular pathway. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of the extracellular environment in the acquisition of specific biological responses.

TGFβ/activin signaling contributes to regeneration of amphibian and reptile appendages

Because axolotls can regenerate whole limbs, they are often used as models to study the underlying mechanisms of vertebrate limb regeneration after amputation. Limb regeneration in axolotls is divided into the preparation phase, which comprises wound healing and blastema formation, and the redevelopment phase, which consists of redifferentiation and growth. Wound healing begins immediately after amputation and involves the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the wounded region to remove cellular debris. Adjacent to the amputation plane, epidermal keratinocytes increase in volume through increasing water absorption and push adjacent keratinocytes to cover the stump. Keratinocytes also undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to acquire a migratory phenotype, resulting in re-epithelialization of the stump (Sader et al. 2019). Once the wound is covered, keratinocytes begin to proliferate, forming a stratified epidermis that is then innervated to generate the signaling center called the apical epithelium cap (AEC). AEC basal keratinocytes produce signals required to promote the recruitment, dedifferentiation, and activation of progenitor cells and fibroblasts harbored in the different tissues of the stump. The dedifferentiated cells begin to proliferate to form the blastema, which is composed of heterogeneous restricted progenitor cells that guide redevelopment of the missing structures (Dall’Agnese and Puri 2016; McCusker et al. 2015). Additionally, blastema formation is promoted by dermal fibroblasts with different positional identities around the limb, which migrate under the AEC and establish the pattern of new limb tissues (Kragl et al. 2009).

TGFβ signaling plays an important role in axolotl limb regeneration. Tgfβ1 expression (Levesque et al. 2007) and the activation of Smad2 and Smad3 was detected early in the preparation phase of limb regeneration (Denis et al. 2016; Levesque et al. 2007) Similarly, the presence of TβRI and TβRII was confirmed in AL-1 cells derived from dermal fibroblasts of axolotl limbs. AL-1 cells treated with TGFβ1 expressed TGFβ signaling target genes, such as PAI-1 and fibronectin at 3 and 72 h post-stimulation, confirming that the TGFβ signaling machinery is present and functionally active during regeneration (Levesque et al. 2007). The critical role of TGFβ signaling during the regeneration of axolotl limbs was supported by experiments in which the persistent treatment of amputated limbs with SB-431542, an inhibitor of Smad-mediated TGFβ/activin signaling, resulted in the blockage of axolotl limb regeneration by reducing cell proliferation and inhibiting formation of the blastema (Levesque et al. 2007). However, the selective inhibitor of Smad3 (SIS3) exerts a minimal effect on limb regeneration, suggesting that Smad2 is a mediator of TGFβ activity for regeneration (Fig. 2a) (Denis et al. 2016).

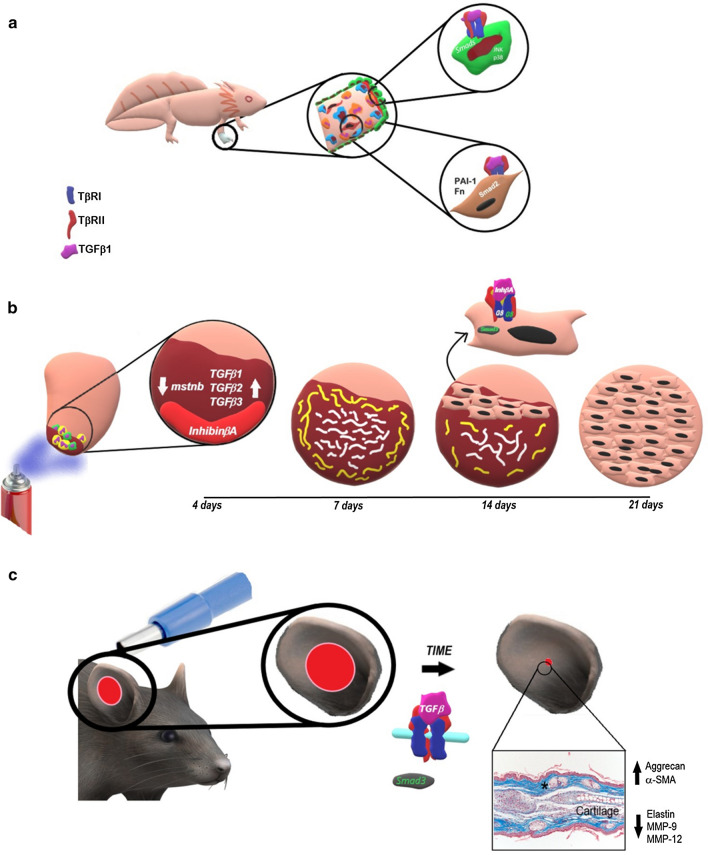

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation regarding the contribution of TGFB/activin signaling to the regeneration of some vertebrate structures. a Loss of function experiments reveal that TGFβ signaling is necessary to induce the proliferation of blastema cells and axolotl limb regeneration; dermal fibroblasts of axolotl limbs show all the components of the TGFβ receptor complex and are responsive to this signal by expressing the TGFβ target genes Fn and Pai-1, suggesting their participation in blastema proliferation possibly through Smad2 activation. In addition, both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways, such as activation of JNK and p38 by TAK1, contribute to re-epithelialization of the wound, inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. b During early phases of regeneration of the zebrafish heart ventricle damaged by cryoinjury, an increase in Tgfβ1, Tgfβ2 and Tgfβ3 expression results in the establishment of transitory scar tissue comprised of a collagen matrix surrounded by a fibrin layer in the infarcted area. In addition, at the beginning of regeneration, expression of inhibinβa and downregulation of mstnb are observed. Inhibinβa contributes to the resolution of transitory scar tissue and promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation by binding to ActRIIA and activating Smad3. c Constitutive activation of TβR1/ALK5 leads closure of the ear hole by a regenerative process in which new cartilage and cutaneous appendage formation are appreciated. These features are possibly achieved through Smad3 activation, resulting in upregulation of α-SMA expression and downregulation of elastin and MMP-9 and MMP-12 expression to promote contraction of the tissue and hole closure

EMT has been recognized as an important process during axolotl limb regeneration, which promotes the migration of epidermal cells to close the wound. Upregulation of EMT markers and the activation of JNK and p38 are observed during the first 2 h after axolotl limb amputation, which remain until the first signs of blastema emergence. Administration of the TAK-1 inhibitor 5Z-7-oxozeanol delayed epithelialization and inhibited expression of some EMT markers. This effect was exacerbated by the coadministration of 5Z-7-oxozeanol and SB431542, indicating that both canonical and noncanonical TGFβ pathways contribute to EMT and re-epithelialization (Fig. 2a) (Sader et al. 2019).

Axolotl skin wounds also heal by regeneration and express Tgfβ1 during the first 24 h post-wound, but not α-sma, a target gene of TGFβ signaling recognized as a molecular marker of myofibroblast differentiation (Denis et al. 2013). Despite the evident participation of TGFβ1 during wound resolution in mammals and axolotls, these data reveal that TGFβ1-mediated genetic regulation differs between mammals and amphibians and that TGFβ1 mediates several species-specific mechanisms for cell modulation.

Another role of TGFβ signaling in amphibian regeneration has been studied in Xenopus tail regeneration. The structure of the Xenopus tail comprises a central notochord, a dorsal spinal cord, lateral muscle mass and vessels located in the mesenchymal space. Despite its anatomical complexity, the tadpole tail regenerates 2 weeks after amputation, with the exception of a refractory period between stages 45 and 47 of its development. In the early phase of Xenopus tail regeneration, an acute inflammatory response and a moderate number of apoptotic cells are present in the injured region (Chen et al. 2014). The epidermis then covers the stump and thickens by several layers of cells that accumulate over a 24-h period. Two days after amputation, the notochord precursor cells surrounding the injured notochord begin to proliferate and form the regenerative bulb. These cells migrate from the proximal-to-distal direction and accumulate to build a cone-shaped cell mass that is evident 3 days post-amputation. As the regenerating notochord continues to elongate, cells in the proximal portion differentiate into vacuolated mature notochord cells. Simultaneously, a terminal bulb in the damaged spinal cord is generated and elongates to form the ependymal tube. On day 4 post-amputation, subpopulations of satellite cells in the muscle region differentiate into myogenic cells, which migrate into the amputated zone, proliferate, and differentiate into myofibers (Mochii et al. 2007; Taniguchi et al. 2008). Tgfβ2 and Tgfβ5 are expressed in tail buds, while Smad2 is activated in the wound epidermis, neural tube, and notochord during the different stages of tail regeneration. Amputated tails treated with SB-431542, an inhibitor of TGFβ/activin signaling, exhibited impaired regeneration by preventing both re-epithelialization and expression of es-1, a marker for wound epidermis and AECs (Sato et al. 2018). In addition, TGFβ signaling inhibition decreases cell proliferation in regenerative buds and inhibits neural tube and notochord differentiation (Ho and Whitman 2008; Sato et al. 2018). The administration of ERK, TGFβ, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling inhibitors during the regeneration of Xenopus tails established that pERK-TGFβ/pSmad2-ROS signaling promotes wound closure after amputation (Fig. 3a). This indicates that TGFβ is part of the regenerative mechanism that involves multiple signaling pathways (Sato et al. 2018).

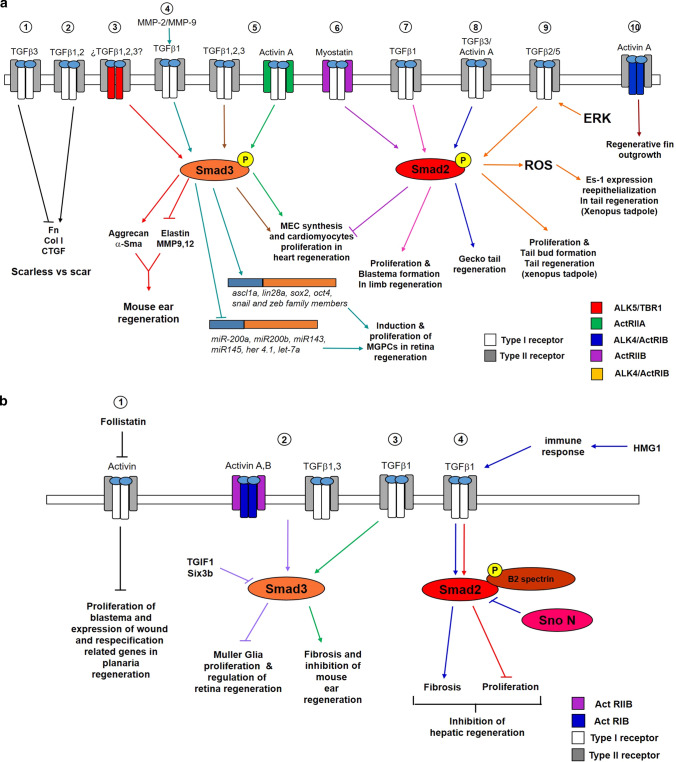

Fig. 3.

a Scheme representing the different regenerative processes promoted by TGFβ/activin signaling. Left to right; (1) TGFβ3 downregulates fibronectin, collagen I and CTGF expression, generating a scarless phenotype (truncated black line). (2) In contrast, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 promote expression of molecules that contribute to scar formation (black arrow). (3) The activation of TβRI/ALK5 results in the phosphorylation of Smad3 to induce aggrecan and α-sma expression (red arrows) and inhibit elastin synthesis and MMP 9 and MMP12 activity (truncated red line), resulting in closure of the mouse ear hole by regeneration. (4) During the regeneration of the zebrafish retina, MMP-2 and MMP-9 promote the formation of active TGFβ1, which is induced through Smad3, expression of regeneration-associated genes (greenish-blue arrow) and repression of some miRNAs (truncated green–blue line) resulting in Müller glia reprogramming and MGPC proliferation. (5) During the regeneration of the zebrafish heart, TGFβ1, TGFβ2, TGFβ3, and activin A via activate Smad3 via ActRIIA to induce extracellular matrix synthesis and cardiomyocyte proliferation in the infarcted area (brown and green arrows). (6) Myostatin inhibit extracellular matrix synthesis and cardiomyocyte proliferation (truncated purple line) through ActRIIB and the activation of Smad2 (purple arrow). (7) During limb regeneration of axolotls, it has been hypothesized that TGFβ1 promotes proliferation and blastema formation via Smad2 (pink arrows). (8) Additionally, Smad2 mediates the activity of TGFβ3 and Activin A to contribute to gecko tail regeneration (dark blue arrow). (9) A sequential interaction among ERK/TGFβ-Smad2/ROS signals supports tail regeneration in Xenopus tadpoles where TGFβ2 and/or TGFβ5 could be involved (orange arrows). (10) Through ActRIB/ALK4, activin contributes to the outgrowth of zebrafish fin during regeneration (dark brown arrow). b Scheme representing different regenerative processes that are inhibited by TGFβ/activin signaling. Left to right: (1) In terms of planarian regeneration, follistatin blocks the anti-regenerative activity of activins that inhibit the proliferation of blastema neoblasts as well as expression of wound and respecification-related genes (black truncated lines). (2) Activin A and Activin B through ActRIIB and ActRIB as well as TGFβ1, TGFβ3 activate Smad3 to inhibit Müller glia proliferation (purple truncated line). This response is controlled by the co-repressors TGIF1 and six3b. (3) TGFβ1 through Smad3 induces fibrosis, resulting in inhibition of mouse ear regeneration during the re-differentiation stage (green arrows). (4) TGFβ1 blocks the proliferation of hepatocytes (red truncated line) via Smad2 and β2SP. Additionally, HMGB1 promotes the immune response, resulting in activation of the TGFβ pathway via Smad2 to induce fibrosis in the liver, disrupting hepatic regeneration (purple arrows). The corepressor SnoN modulates the fibrotic activity of TGFβ

Unlike Xenopus, some reptiles, such as lizards and geckos, exhibit a well-defined blastema structure and folding inward of the apical wound epidermis to generate an epidermal cup or epidermal peg during tail regeneration (Alibardi 2016). During the growth and differentiation phases, mesenchymal-like cells localized in the proximal area of the blastema, which is in contact with the muscle and vertebrae of the original tissue, aggregate to form precursors of cartilage and muscle. An ependymal tube extending from the spinal cord makes contact with the epidermal peg, and chondrocyte precursors surrounding the ependymal tube differentiate into cartilage, while multinucleates myotubes form bundles of new muscle tissue (Alibardi 2014). In contrast with axolotl limb and Xenopus tail regeneration, TGFβ1 expression is absent during blastema formation in the regenerating tail of the leopard gecko, Eublepharis macularius. TGFβ1 expression is present only during the tail growth and differentiation stages; however, there is a high presence of pSmad2 in all regenerative phases, indicating that the Smad pathway is activated by other members of the TGFβ/activin subfamily. In fact, qRT-PCR analysis showed a slight increase in Tgfβ3 expression but significantly higher levels of the activin βa subunit with respect to Tgfβ1, Tgfβ2 and Bmp-2, suggesting that activins act on specific spatial–temporal patterns during gecko tail regeneration (Fig. 3a) (Gilbert et al. 2013).

The contribution of TGFβ/activin signaling to heart and fin regeneration in zebrafish

Among the different vertebrate models, zebrafish (Danio rerio) features a wide variety of biological and structural conditions for the study of regeneration (Mokalled and Poss 2018). The heart of a zebrafish is capable of regenerating after cryoinjury-induced infarction. One day post cryoinjury (dpci), the damaged ventricular area exhibits extensive cardiomyocyte death and an enhanced inflammatory response to remove necrotic cell debris. At 4 dpci, mesenchymal cells begin to surround the damaged myocardium. At 7 dpci, a fibrin layer is deposited around the outer wound margin, and a collagen network is observed at the center of the infarcted area, substituting for the necrotic tissue. At 14 dpci, turnover of fibrin borders begins and is replaced by myocytes, while abundant collagen fibers fill the ventricular area under repair. From 21 to 30 dpci, the fibrin matrix is fully remodeled, and cardiomyocytes start to invade the area under repair, replacing the collagen matrix with new myocardium (Chablais et al. 2011). This process provides evidence that transient scar generation is necessary for complete myocardium regeneration, in which TGFβ signaling plays a key role since the beginning of the process. Smad3 activation and expression of Tgfβ1, Tgfβ2 and Tgfβ3 are limited to the injured zone at 4 dpci. Exposing the heart of the infarcted fish to SB-431542 prevents the synthesis of ECM in the damaged region, resulting in both morphological alterations to the heart and inhibition of regeneration due to the impairment of cardiomyocyte proliferation at the wound site (Chablais and Jazwinska 2012). In addition to the Tgfβ isoforms, expression of the inhibin subunit β Aa (inhbaa or activin β Aa) is notably induced in the zebrafish heart ventricular apex. Conversely, the myostatin B gene (mstnb), another member of the TGFβ superfamily that is expressed in the ventricular wall of a healthy heart, decreases its expression after heart damage. Interestingly, mstnb overexpression and inhbaa inhibition maintain fibrotic tissue and decrease cardiomyocyte proliferation, resulting in impaired heart regeneration. An analysis at 14 dpci revealed that inhbaa overexpression increased the number of pSmad3-positive cardiomyocytes near the infarcted region, while overexpression of mstnb decreased them. Complementary heart development experiments demonstrated that myostatin B and inhibin βa display antagonistic effects during heart regeneration by interacting with different type II activin receptors and by activating different Smads. Myostatin B activates Smad2 through binding to ActRIIB, resulting in inhibition of cardiomyocyte proliferation. Conversely, inhibin βA interacts with ActRIIA to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration through Smad3 activation (Figs. 2b, 3a) (Dogra et al. 2017). Together, these experiments highlight the importance of the regulation of ligand expression and the specificity of the ligand-receptor in the generation of different biological responses.

Participation of TGFβ/activin signaling during regeneration of the tail fin of zebrafish has also been demonstrated. The specific region of a zebrafish caudal fin that is able to regenerate consists of 16–18 segmented rays connected by interray tissue, where each ray is a spine-like skeletal element constituted by two structures: lepidotrichia and actinotrichia. Lepidotrichia are pairs of long, segmented, arch-shaped bones that are complementary to each other and that enclose vascular and innervated tissue. Actinotrichia are mineralized brush-like fibrils located in the distal end of lepidotrichia that supply ray tip stiffness and elasticity (Konig et al. 2018; Laforest et al. 1998). Zebrafish fin regeneration requires several steps: wound healing, stump activation, blastema formation and regenerative outgrowth (Chassot et al. 2016). The wound healing step occurs a few hours after amputation and consists of rapid re-epithelialization without a remarkable change in the distribution of neutrophils with respect to the proximal site of the undamaged fin (Chassot et al. 2016). Twenty-four hours post-amputation (hpa), blastema formation occurs, which is performed by tissue-specific progenitor cells from the stump. At 48 hpa, blastema tissue is clearly observed under the re-epithelialized area of the wound epidermis and above the rays and interrays of the stump (Chassot et al. 2016; Jazwinska et al. 2007). During regenerative outgrowth, blastema cells progressively differentiate by moving away from the wound epidermis, giving rise to progenitor cells of connective, nervous, skeletal and vascular tissues. Lepidotrichia bone regeneration is generated by blastema cell differentiation in scleroblasts that synthesize and deposit the lepidotrichia matrix beneath the subepidermal basal membrane (Laforest et al. 1998). Two days post-amputation (dpa), actinotrichia fibrils are observed in the new tissue and are progressively elongated, reaching their maximal size at 5 dpa. During this time, actinotrichia fibers are displaced from lepidotrichia for bone regeneration (Konig et al. 2018). Inhibition of the TGFβ/activin signal by SB-432542 immediately after resection results in the blockade of fin regeneration by impairing blastema formation; this takes place both by arresting cellular proliferation and by disorganizing the ECM. If SB-431542 is administered 2 dpa, after the onset of blastema formation, shorter fin outgrowth and interrupted actinotrichia formation are observed. These data indicate that the TGFβ/activin pathway contributes to both the formation and maintenance of actinotrichia and therefore indirectly to the establishment of lepidotrichia (Konig et al. 2018). In situ hybridization of actβa during fin regeneration showed that this transcript is expressed early (6 hpa) in the mesenchymal border near the amputated fin rays. In addition, 72 hpa, actβa is also expressed in the blastema. Specific participation of the activin pathway in fin regeneration has been demonstrated by electroporation of Alk4 morpholino, where an antisense oligomer prevents the translation of Alk4 into the regenerating fins. This process resulted in reduced fin outgrowth, demonstrating the importance of ActRIB/Alk4 signaling in zebrafish fin regeneration (Fig. 3a) (Jazwinska et al. 2007).

The inhibitory role of TGFβ/activin signaling in regeneration: from complete bodies to liver

Activins inhibit the regeneration of planarians by regulating the proliferation of neoblasts

Although several reports support the positive role of TGFβ/activin stimulation during regeneration, others have reported a negative role. Unlike the restorative impact that activin signaling has on zebrafish caudal fins, their contribution is inhibitory during planarian regeneration. Planarians are flatworms belonging to the Platyhelminthes family with nearly unlimited regenerative abilities, rendering them excellent models for stem cell-based regeneration studies (Reddien and Sanchez Alvarado 2004). Planarians contain neoblasts, a type of pluripotent stem cell distributed throughout the mesenchyme, which is necessary for planarian functionality. Upon amputation, neoblasts begin initial mitosis 6 h after damage, and 48 h later, a second wave of mitosis peaks in areas concentrated around the wound site to form the blastema (Gehrke and Srivastava 2016). The anti-regenerative role of activin signaling during planarian regeneration was demonstrated by experimentally manipulating follistatin, an extracellular antagonist that binds to activins and blocks their function (Thompson et al. 2005). Two activin homologs, Smed-activin-1 (act-1) and Smed-activin-2 (act-2), are expressed throughout the intestine of uninjured Schmidtea mediterranea, but only act-2 is expressed after injury at wound sites, from 6 h post-amputation and persisting until 48 h, similar to follistatin expression (Gavino et al. 2013). Planarians fed bacteria expressing follistatin dsRNA generate follistatin RNA interference [fst(RNAi)]. When an fst(RNAi) planarian was amputated, it failed to produce a blastema due to the reduced neoblast proliferation and the consequent lack of progenitor cells. In addition, fst(RNAi) animals exhibited dysregulated expression of wound-response genes and genes related to re-specification. Similarly, fst(RNAi) flatworms treated with act-1 or act-2 RNAi exhibited normal phenotypes, and no regenerative defects were observed in fst(RNAi) animals, indicating that follistatin promotes regeneration by inhibiting the function of activins (Fig. 3b) (Gavino et al. 2013; Sánchez-Alvarado 2013).

Compensatory regeneration of the liver is modulated by TGFβ signaling

Mammalian liver regeneration is considered a compensatory hypertrophy due to the liver’s capacity to increase its mass after partial removal (Mao et al. 2014). The resection of the two anterior lobes in murines reduces the liver by 70%. Within 1–2 weeks, the remaining lobes expand to compensate for the lost mass and functional demand; thus, the removed lobes are not reconstituted, but missing tissue is re-established primarily by hepatocyte proliferation (Martins et al. 2008; Mastellos et al. 2013). It has been demonstrated that TGFβ signaling modulates mouse liver regeneration, primarily inhibiting hepatocyte proliferation and inducing hepatic fibrosis. Tgfβ1 expression and Smad2 activation occur during the first phase of hepatic regeneration (from 2 h), the phase in which hepatocyte proliferation takes place. However, there is also an increase in the expression of transcriptional coregulators, ski-related novel gene (SnoN) and yes-associated protein (YAP)-1. This leads to the formation of SnoN-Smad2/3 and YAP-1-Smad2 complexes, resulting in inhibition of the anti-proliferative and pro-fibrotic roles of TGFβ in the injured liver, allowing hepatic regeneration to proceed (Fig. 3b) (Macias-Silva et al. 2002; Oh et al. 2018). Another piece of evidence concerning the anti-proliferative role of TGFβ during hepatic regeneration was shown in heterozygous knockout of β2SP in mice. Β2SP is an adaptor protein associated with Smad3 and Smad4 that contributes to the localization of Smad3 at the cell surface membrane, as well as the translocation of Smad4 to the nucleus. In addition, β2SP acts as a mediator of the transcriptional response induced by TGFβ (Tang et al. 2003). β2SP exhibits low expression during the initial phases of mouse hepatic regeneration, but it increases as regeneration progresses, peaking 72 h following hepatectomy. Heterozygous β2SP knockout mice (β2SP+/−) exhibit an expanded population of progenitor cells in response to hepatic damage, indicating that TGFβ signaling through β2SP inhibits the expansion of these progenitor cells (Fig. 3b) (Thenappan et al. 2010). Notwithstanding, β2SP+/− mouse livers show decreased hepatic proliferation at 48 h post-hepatectomy due to elevated expression of cell cycle inhibitors (Thenappan et al. 2011). These observations suggest that expression levels of β2SP could influence the different proliferative responses triggered by TGFβ signaling during hepatic regeneration.

The pro-fibrotic role of TGFβ signaling in liver regeneration has been evidenced by the haploinsufficiency of digestive organ expansion factor (Def) (def+/−) in adult zebrafish liver. Def codes for a nucleolar protein that forms a complex with chaplain. This complex induces the degradation of p53, a protein involved in the cell cycle and stress. Findings in def+/− zebrafish indicate that during liver regeneration, Def modulates TGFβ activity and fibrosis via p53 degradation. In a widespread fashion, the p53 pathway upregulates expression of the proinflammatory factor high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), promoting the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)1β, IL6, and IL8, which are responsible for activating TGFβ/pSmad2 signaling and fibrosis (Fig. 3b) (Zhu et al. 2014).

Another possible aspect related to the fibrotic response triggered by TGFβ/activating signaling that impairs liver regeneration comes from studies establishing that TGFβ1 and activin A act as signals of EMT maintenance in hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs). HPCs reside in the distal part of the biliary tree and exhibit a partial EMT state that may contribute to liver fibrosis during chronic liver injury (Kaur et al. 2015). Discovery of the role of TGFβ/activin signaling in the maintenance of the partial EMT state of HPCs comes from TGFβ1 and Smad4 knockdown, Activin A inhibition or SB431542 administration studies performed in HPC-derived cell lines resulted in the upregulation of epithelial markers and the migration of HPCs, as well as the reduction of mesenchymal markers, indicating a role of TGFβ and activins in the EMT process. These results highlight the importance of TGFβ/activin signaling in the maintenance of partial EMT in HPC and suggest that this behavior may prevent liver regeneration (Wu et al. 2018).

Controversial effects of TGFβ signaling on regeneration: the retina of the zebrafish and the ears of the mouse

Zebrafish retina

Adult zebrafish regenerate their retinas by activating and reprogramming Müller glia. This action generates all neurogenic progenitors, including rod progenitors, which form photoreceptor cells (Wan and Goldman 2016). The zebrafish retina is organized into the following three layers: (1) the ganglion cell layer (GCL), which is the layer in contact with the light and harbors ganglion cells; (2) the middle or inner nuclear layer (INL), which shelters horizontal, bipolar, and amacrine cells; and (3) the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which is composed of rod and cone photoreceptors. Although the cell bodies of Müller glia reside in the INL, their dendritic processes penetrate all retinal layers and contact neighboring neurons (Wan and Goldman 2016). Following injury, genetic reprogramming of Müller glial cells into Müller glia-derived progenitor cells (MGPCs) causes their nuclei to migrate through their cytoskeleton and to be directed toward the ONL. Afterward, asymmetric cell division of Müller glia gives rise to a multipotent progenitor that amplifies the progenitor population. These cells migrate into all retinal layers and differentiate into the neurons corresponding to each layer (Chohan et al. 2017; Goldman 2014; Wan and Goldman 2016).

There are two different approaches regarding the role of TGFβ signaling with respect to retinal regeneration of retina, one as a promoter and the other as a negative regulator. Evidence for the role of TGFβ in the activation of Müller glia comes from mechanical retinal injury induced with a 30-G needle. This injury caused several biochemical and molecular events, resulting in an upregulation of effector genes regulated by TGFβ: from 3 h post-injury (hpi), tgfbi, smad7, and some members of the snail gene family are upregulated, while they decrease 4 days post-injury (dpi). However, the rapid increase in pSmad3 from 4 h was maintained throughout the regenerative process of the retina (Sharma et al. 2020). Gain- and loss-of-function experiments by TGFβ1 and SB431542 administration revealed that TGFβ signaling through Smad3 promotes the proliferation rate of MGPCs, as well as the expression of some regeneration-associated genes, such as achaete-scute homolog 1 (ascl1a), lin-28 homolog A (lin28a), SRY-box transcription factor 2 (sox2), octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (oct4), and histone deacetylase 1 (hdac1). This increase in the expression of regeneration-associated genes is mediated by the downregulation of let-7a microRNA by TGFβ signaling, resulting in the differentiation of retinal cells. TGFβ signaling also reduced expression of the microRNAs miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-143, and miR-145, resulting in expression of EMT activators from snail and zeb family members to induce reprogramming of Müller glia (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the proliferation of MGPCs mediated by TGFβ signaling at 4 dpi depends on MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities, as demonstrated by morpholine injection to downregulate the expression of mmp2 and mmp9. In addition, overexpression of regeneration-associated genes, such as ascl1a, lin28a, sox2, and oct4, which increase the number of MGPCs, combined with SB3CT, an inhibitor of MMP-2/MMP-9 activities, significantly reduced the number of MGPCs, indicating that these metalloproteinases are necessary for the efficient functioning of regeneration-associated genes to promote MGPCs by reprogramming Müller Glia. Notably, the effect of TGFβ signaling on the late phase of retinal regeneration is contrary to that from the beginning. The administration of SB431542 at 5 dpi increases the proliferation of MGPCs and the expression of regeneration-associated genes while downregulating nucleosome remodeling and histone deacetylation family members (NuRDs) and the negative regulator of cell proliferation, her4.1. These results indicate that during the late phase of zebrafish retinal regeneration, TGFβ is involved in the cell cycle exit of MGPCs (Sharma et al. 2020).

On the other hand, an inhibitory function of TGFβ signaling in retinal regeneration has also been reported. TGFβ-induced factor homeobox 1 (TGIF1) and SIX homeobox 3b (Six3b), both corepressors of TGFβ signaling, are expressed in Müller glia in adult zebrafish immediately following the destruction of photoreceptors by intense light. In contrast, expression of actRIB, actRIIB, and Tgfβ1 is downregulated. The importance of the blocking function of TGFβ-Smad2/3 signaling in the regenerative response mediated by Müller glia has been demonstrated both in Tgif1-/- fishes and by inhibiting six3a and six3b through morpholinos injection, leading to a reduction in photoreceptor regeneration by reduced proliferation of Müller glia progeny (Fig. 3b) (Lenkowski et al. 2013). In addition, it has been reported that Smad3 is activated in proliferating Müller glial cells 5 days after inducing rod photoreceptor degeneration by N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU). This coincides with the high expression of activin A, activin B, and tgfβ3 in the INL of the retina, indicating that the Smad3-mediated signal is activated by those ligands. Early administration of the SB431542 inhibitor during the recovery of MNU-induced retinal degeneration resulted in increased cell proliferation in the ONL, rapidly restoring damaged tissue and revealing the anti-proliferative effect of TGFβ signaling on Müller glial cells (Tappeiner et al. 2016).

Similarly, early administration of both SIS3 and SB-431542 to NMDA-induced damaged chick retinas increased the proliferation of MGPCs. Furthermore, TGFβ2 administration suppressed proliferating MGPCs and downregulated the retinal stem cell markers pax6 and klf5, as well as the MGPC marker egr1, indicating that TGFβ signaling interferes with the reprogramming of Müller glia into proliferating progenitors (Todd et al. 2017). In this model, Smad2 is distributed throughout the cytoplasm in Müller glia during the regeneration process, indicating an inactive state of TGFβ signaling. On the other hand, BMP-activated phosphorylated Smads (Smad 1/5/8) were observed 24 h post-damage. Applying dorsomorphin homologue 1 (DMH-1), an inhibitor of the BMP signaling pathway, to NMDA-damaged chick retinas decreased MGPC proliferation. This indicates antagonism between TGFβ and BMP signals with respect to Müller glial reprogramming (Todd et al. 2017). Contradictory data on the positive or negative role of TGFβ signaling during retinal regeneration are obscure, although the mechanisms of lesion may exert an influence on the role of this signaling. While the withdrawal of complete cell layers due to mechanical damage might promote a regenerative response by TGFβ signaling, physical and/or chemical damage might generate an inhibitory response of this pathway in retinal regeneration.

Mouse ear hole

The role of TGFβ signaling in mammalian regeneration has been studied by treating the C57BL/6 mouse strain with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. This compound generates a point mutation that results in the substitution of an arginine with a glutamine at position 242 of TGFβRI, partially activating its kinase activity. The impact of this hyperresponsiveness of the mutated receptor on regeneration was analyzed in the healing process of a 2-mm hole placed in the ears of mouse strains that carry the mutation. Five weeks post-injury, the wound area of the mutant mice was reduced by 95% compared to only a 45% reduction in wild type mice. Furthermore, the healed ears of the mutated mice demonstrated an increase in the synthesis of aggrecan, correlating with the formation of new cartilage. Along with cartilage, new hair follicles and sebaceous glands were also formed in the generated tissue (Fig. 2c) (Liu et al. 2011). This positive role of TGFβ signaling in ear hole regeneration was supported by Smad3-null mice, which exhibited ear wound enlargement due to an increase in dermal cell apoptosis and elastin synthesis, resulting in increased ear elasticity. Additionally, low levels of α-SMA and high activity of MMP-9 and MMP-12 were observed in these mice, indicating that wound contraction contributes to closing the ear hole (Fig. 2c) (Arany et al. 2006; Ashcroft et al. 1999). However, the blocking function of TGFβ signaling has also been demonstrated during the redifferentiation phase of limited regeneration of ear holes. It has been reported that a hole 2 mm in diameter made in the ears of middle-aged female mice heals with regenerative characteristics, highlighting rapid reepithelization and wound healing, the formation of a blastemal-like structure and limited tissue differentiation (Reines et al. 2009; Abarca et al. 2017). In that model, the blockade of TGFβ signaling by SB-431542 administration at the beginning of the redifferentiation phase promoted the growth of blastema-like structures and the formation of cartilage and muscle. This phenotype was associated with a decrease in Smad3 phosphorylation, α-SMA expression and collagen deposition, indicating that smad3-mediated TGFβ signaling is a profibrotic factor and an inhibitory component of the differentiation phase of the limited regeneration of the mouse ear hole (Abarca-Buis et al. 2020). These reports suggest that TGFβ signaling could act in two ways. First, during the early and middle time points of ear healing, TGFβ signaling promotes regeneration; however, as has been reported, TGFβ1 expression is absent at those times (Abarca-Buis et al. 2020), suggesting the presence of TGFβ1 inhibitory factors. Second, during the redifferentiation phase, TGFβ1 is expressed, but it works as a profibrotic factor that downregulates the regenerative phenotype. Controlling TGFβ signaling during different time points of ear healing could increase or complete its regenerative ability.

The antagonistic responses induced by TGFβ on regeneration may be due to multifactorial events

The several antagonistic responses that TGFβ signaling demonstrates during regeneration could be due to multiple factors, including the presence or absence of intracellular and extracellular regulators of the pathway, specific functions of the pathway’s components, the type of signal transduction that is activated, or interaction of TGFβ signaling concomitant with other intracellular pathways.

An interesting proposal is the possible differential role between Smad2 and Smad3. During the preparation phase of axolotl limb regeneration, both phosphorylated forms of Smad2 and Smad3 are present, and the administration of SB431542, an inhibitor of the canonical TGFβ pathway, results in disruption of regeneration. However, the application of SIS3, a selective inhibitor of Smad3 phosphorylation, exerted a minimal effect on limb regeneration, indicating that Smad2 is the transducer of the TGFβ signal that promotes blastema formation, allowing regeneration to proceed (Denis et al. 2016). In fact, a profibrotic role has been attributed to Smad3 in several systems (Flanders 2004). During the wound-healing process in mice lacking Smad3, there is a decrease in TGFβ levels, which might cause a disruption in fibroblast recruitment into the wound area, as well as collagen production (Ashcroft et al. 1999). Additionally, compared to skin fibrosis induced by irradiation in normal mice, irradiated Smad3 KO mice practically did not develop acanthosis or the typical thickened collagen fiber pattern (Flanders 2004; Flanders et al. 2002). Similarly, during limited mouse ear regeneration, a decrease in p-Smad3 levels and fibrosis was also observed when SB431542 was administered, resulting in larger cartilage nodules and muscle areas (Abarca-Buis et al. 2020). Notwithstanding this, not only can different responses be obtained by Smad2 or Smad3 activities, sometimes they are antagonistic. Such is the case for the regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation during regeneration of the zebrafish heart, while inhbaa, which encodes the inhibin βA subunit, promotes cell proliferation through Smad3 activation, and mstnb, which encodes myostatin, inhibited proliferation through Smad2 (Dogra et al. 2017).

Another antagonistic effect is observed during cartilage maintenance; TGFβ1 induces PAI, fibronectin, and col II expression through ALK5-Smad2/3, while these same genes are repressed when TGFβ1 turns on the ALK1-Smad1/5/8 pathway (Finnson et al. 2008, 2010). Additionally, through this last mechanism, TGFβ induces expression of Mmp-13, Id-1, and Col I, resulting in a pathological phenotype, such as osteoarthritis (Blaney Davidson et al. 2009). It appears that the TGFβ coreceptor endoglin is key for activation of the ALK1-Smad1/5/8 signal (Finnson et al. 2010). Whether this TGFβ-mediated alternative pathway may contribute to the acquisition of a nonregenerative phenotype in mammals or in other systems is unknown.

Other actors that might be involved in amplifying or downregulating the regenerative responses triggered by the TGFβ/TβRII/TβRI complex are mediators of Smad-independent signaling. For example, it has been reported that both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signals, where TAK-1-stimulated p-38 and JNK activation are involved, are necessary for re-epithelialization of the axolotl limb stump (Sader et al. 2019). It would interesting to assess whether MAP kinases activated by TGFβ through TAK-1, together with canonical Smad signaling, might increase or accelerate regenerative features in nonregenerative or limited regenerative systems, such as the mouse ear. However, the possibility that the nondependent Smad signal might act as a negative regulator of some events involved in regeneration should not be ruled out. In fact, in epithelial renal carcinoma cells, fibrosis associated with the expression of fibronectin is induced by Smad-dependent mechanisms and TGFβ-activated p38. Additionally, the activation of ERK1/2 by TGFβ contributes, similar to Smad, to myofibroblast differentiation in human skin and breast fibroblasts (Carthy et al. 2015; Laping et al. 2002). On the other hand, in some situations, the Smad pathway disrupts regeneration, such as retinal regeneration in zebrafish or chicken; in those cases, the cellular context should be considered. The cellular context is defined as the intracellular molecular machinery present in a cell or in a group of cells that exerts an impact on the cellular response to a specific stimulus. Therefore, the level of the presence or expression of certain coactivators, corepressors, or regulators of TGFβ signaling in determined cells contributes to the generation of specific responses. For example, Smurf-2 was discovered as a ubiquitin ligase for R-Smad and the TGF-β receptor complex for degradation; therefore, it acts as a negative regulator of the TGFβ pathway. However, it also mediates degradation of the corepressors SnoN and Smad7. In that case, Smurf-2 promotes activation of TGFβ signaling. High levels of SMURF-2 are found in fibroblasts of scleroderma and hypertrophic scars, as well as during the development of renal fibrosis. Apparently, under these pathological conditions, a high concentration of Smurf-2 promotes the degradation of Sno-N, Ski, and Smad7, contributing to the progression of fibrosis (Fukasawa et al. 2004, 2006; Zhang et al. 2012).

The mechanisms by which TGFβ signaling generates differential responses that regulate the regenerative response have been very complex to elucidate. However, the determination of expression levels and roles of the intrinsic components or regulators that interact with the TGFβ signal in the different animal models will help us to acquire a better understanding of how this pathway has changed through animal evolution to generate several responses related to wound healing and regeneration. In addition, we will be able to develop efficient therapies based on the TGFβ system to improve wound healing by means of a regenerative process.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Although TGFβ/activin signaling plays a clear role in regeneration by regulating matrix remodeling, proliferation, and re-epithelialization, the cellular and molecular mechanisms that control these processes remain unknown. Although some studies have described the different activities of Smad2 and Smad3, TGFβ/activin signaling is part of a complex network of interactions among several pathways that are necessary to regulate specific regenerative events. It remains unknown whether Smad-independent or ALK1-Smad1/5/8 pathways participate in other physiologic and cellular processes, such as inflammation, apoptosis, the establishment of blastema, and differentiation; this is a testament to the complexity of regeneration. Further research on these topics could help explain some of the paradoxical actions of TGFβ/activin signaling. Furthermore, it could bring to light why TGFβ family members induce diametrically opposed responses under certain situations, despite the presence of a common canonical intracellular pathway, one example being the impact of TGFβ1 and TGFβ3 on the fibrotic response. With a more concrete understanding of the TGFβ/activin hierarchy within signaling networks and with a more thorough recognition of its mediators and effectors, it is hoped that human regeneration therapies can be improved.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

All authors agreed to the conduct of this review and its final contents.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish this work in the Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abarca-Buis RFC-FM, Garciadiego-Cazares D, Krötzsch E. Control of fibrosis by TGFB signalling modulation promotes redifferentiation during limited regeneration of ear mouse. Int J Dev Biol. 2020;64(7–8–9):423–432. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.190237ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alibardi L. Histochemical, biochemical and cell biological aspects of tail regeneration in lizard, an amniote model for studies on tissue regeneration. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2014;48:143–244. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alibardi L. Immunolocalization of FGF8/10 in the Apical Epidermal Peg and Blastema of the regenerating tail in lizard marks this apical growing area. Ann Anat. 2016;206:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany PR, et al. Smad3 deficiency alters key structural elements of the extracellular matrix and mechanotransduction of wound closure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9250–9255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602473103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft GS, et al. Mice lacking Smad3 show accelerated wound healing and an impaired local inflammatory response. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:260–266. doi: 10.1038/12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeld KA, Amini-Nik S, Alman BA. Cutaneous wound healing: recruiting developmental pathways for regeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2059–2081. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilandzic M, Stenvers KL. Betaglycan: a multifunctional accessory. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;339:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney Davidson EN, et al. Increase in ALK1/ALK5 ratio as a cause for elevated MMP-13 expression in osteoarthritis in humans and mice. J Immunol. 2009;182:7937–7945. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocharov EV, Blommers MJ, Kuhla J, Arvinte T, Burgi R, Arseniev AS. Sequence-specific 1H and 15 N assignment and secondary structure of transforming growth factor beta3. J Biomol NMR. 2000;16:179–180. doi: 10.1023/a:1008315600134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowska J, Kopcewicz M, Kur-Piotrowska A, Szostek-Mioduchowska AZ, Walendzik K, Gawronska-Kozak B. Effect of TGFbeta1, TGFbeta3 and keratinocyte conditioned media on functional characteristics of dermal fibroblasts derived from reparative (Balb/c) and regenerative (Foxn1 deficient; nude) mouse models. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:149–163. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2836-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard KM, Longaker MT, Lorenz HP. Fetal wound healing: current biology. World J Surg. 2003;27:54–61. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6737-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BM. Principles of regenerative biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Carthy JM, Sundqvist A, Heldin A, van Dam H, Kletsas D, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Tamoxifen inhibits TGF-beta-mediated activation of myofibroblasts by blocking non-Smad signaling through ERK1/2. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:3084–3092. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chablais F, Jazwinska A. The regenerative capacity of the zebrafish heart is dependent on TGFbeta signaling. Development. 2012;139:1921–1930. doi: 10.1242/dev.078543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chablais F, Veit J, Rainer G, Jazwinska A. The zebrafish heart regenerates after cryoinjury-induced myocardial infarction. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassot B, Pury D, Jazwinska A. Zebrafish fin regeneration after cryoinjury-induced tissue damage. Biol Open. 2016;5:819–828. doi: 10.1242/bio.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Love NR, Amaya E. Tadpole tail regeneration in Xenopus. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:617–623. doi: 10.1042/BST20140061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chohan A, Singh U, Kumar A, Kaur J. Muller stem cell dependent retinal regeneration. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;464:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Agnese A, Puri PL. Could we also be regenerative superheroes, like salamanders? BioEssays. 2016;38:917–926. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis JF, Levesque M, Tran SD, Camarda AJ, Roy S. Axolotl as a model to study scarless wound healing in vertebrates: role of the transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2013;2:250–260. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis JF, Sader F, Gatien S, Villiard E, Philip A, Roy S. Activation of Smad2 but not Smad3 is required to mediate TGF-beta signaling during axolotl limb regeneration. Development. 2016;143:3481–3490. doi: 10.1242/dev.131466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra D, Ahuja S, Kim HT, Rasouli SJ, Stainier DYR, Reischauer S. Opposite effects of Activin type 2 receptor ligands on cardiomyocyte proliferation during development and repair. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1902. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01950-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebisawa T, Fukuchi M, Murakami G, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Imamura T, Miyazono K. Smurf1 interacts with transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor through Smad7 and induces receptor degradation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12477–12480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c100008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti P, Géraudie J. Cellular and molecular basis of regeneration: from invertebrates to humans. Hoboken: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Finnson KW, Parker WL, ten Dijke P, Thorikay M, Philip A. ALK1 opposes ALK5/Smad3 signaling and expression of extracellular matrix components in human chondrocytes. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:896–906. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnson KW, Parker WL, Chi Y, Hoemann CD, Goldring MB, Antoniou J, Philip A. Endoglin differentially regulates TGF-beta-induced Smad2/3 and Smad1/5 signalling and its expression correlates with extracellular matrix production and cellular differentiation state in human chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:1518–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC. Smad3 as a mediator of the fibrotic response. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:47–64. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders KC, et al. Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against cutaneous injury induced by ionizing radiation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64926-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa H, et al. Down-regulation of Smad7 expression by ubiquitin-dependent degradation contributes to renal fibrosis in obstructive nephropathy in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8687–8692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400035101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa H, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of SnoN and Ski is increased in renal fibrosis induced by obstructive injury. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1733–1740. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher AJ, Schiemann WP. Src phosphorylates Tyr284 in TGF-beta type II receptor and regulates TGF-beta stimulation of p38 MAPK during breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3752–3758. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavino MA, Wenemoser D, Wang IE, Reddien PW. Tissue absence initiates regeneration through follistatin-mediated inhibition of activin signaling. Elife. 2013;2:e00247. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke AR, Srivastava M. Neoblasts and the evolution of whole-body regeneration. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;40:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert RW, Vickaryous MK, Viloria-Petit AM. Characterization of TGFbeta signaling during tail regeneration in the leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius) Dev Dyn. 2013;242:886–896. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingery A, Bradley EW, Pederson L, Ruan M, Horwood NJ, Oursler MJ. TGF-beta coordinately activates TAK1/MEK/AKT/NFkB and SMAD pathways to promote osteoclast survival. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2725–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold E, et al. Activin C antagonizes activin A in vitro and overexpression leads to pathologies in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:184–195. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D. Muller glial cell reprogramming and retina regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:431–442. doi: 10.1038/nrn3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Rosendahl A, Sideras P, ten Dijke P. Balancing the activation state of the endothelium via two distinct TGF-beta type I receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:1743–1753. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero-Juarez CF, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myeloid-derived adipocyte progenitors in murine skin wounds. Nat Commun. 2019;10:650. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanyu A, Ishidou Y, Ebisawa T, Shimanuki T, Imamura T, Miyazono K. The N domain of Smad7 is essential for specific inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1017–1027. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Role of Smads in TGFbeta signaling. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:21–36. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck AP, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1: three-dimensional structure in solution and comparison with the X-ray structure of transforming growth factor beta 2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8517–8534. doi: 10.1021/bi9604946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DM, Whitman M. TGF-beta signaling is required for multiple processes during Xenopus tail regeneration. Dev Biol. 2008;315:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honardoust D, Varkey M, Marcoux Y, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Reduced decorin, fibromodulin, and transforming growth factor-beta3 in deep dermis leads to hypertrophic scarring. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:218–227. doi: 10.1097/bcr.0b013e3182335980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Schor SL, Hinck AP. Biological activity differences between TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta3 correlate with differences in the rigidity and arrangement of their component monomers. Biochemistry. 2014;53:5737–5749. doi: 10.1021/bi500647d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson D, Saintigny G, Zeypveld J, Mahe C, El Ghalbzouri A. TGF-beta1 induces differentiation of papillary fibroblasts to reticular fibroblasts in monolayer culture but not in human skin equivalents. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:342–348. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwinska A, Badakov R, Keating MT. Activin-betaA signaling is required for zebrafish fin regeneration. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1390–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Siddiqui H, Bhat MH. Hepatic progenitor cells in action: liver regeneration or fibrosis? Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2342–2350. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Henen MA, Hinck AP. Structural biology of betaglycan and endoglin, membrane-bound co-receptors of the TGF-beta family. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019;244:1547–1558. doi: 10.1177/1535370219881160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig D, Page L, Chassot B, Jazwinska A. Dynamics of actinotrichia regeneration in the adult zebrafish fin. Dev Biol. 2018;433:416–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragl M, Knapp D, Nacu E, Khattak S, Maden M, Epperlein HH, Tanaka EM. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature. 2009;460:60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforest L, Brown CW, Poleo G, Geraudie J, Tada M, Ekker M, Akimenko MA. Involvement of the sonic hedgehog, patched 1 and bmp2 genes in patterning of the zebrafish dermal fin rays. Development. 1998;125:4175–4184. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.21.4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laping NJ, et al. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-beta type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:58–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, et al. TGF-beta activates Erk MAP kinase signalling through direct phosphorylation of ShcA. EMBO J. 2007;26:3957–3967. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenkowski JR, Qin Z, Sifuentes CJ, Thummel R, Soto CM, Moens CB, Raymond PA. Retinal regeneration in adult zebrafish requires regulation of TGFbeta signaling. Glia. 2013;61:1687–1697. doi: 10.1002/glia.22549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, et al. Transforming growth factor: beta signaling is essential for limb regeneration in axolotls. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Nagarajan RP, Vale W, Chen Y. Phosphorylation regulation of the interaction between Smad7 and activin type I receptor. FEBS Lett. 2002;519:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, et al. Regenerative phenotype in mice with a point mutation in transforming growth factor beta type I receptor (TGFBR1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14560–14565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111056108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Casillas F, Wrana JL, Massagué J. Betaglycan presents ligand to the TGF beta signaling receptor. Cell. 1993;73:1435–1444. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz M, Knaus P. Integration of the TGF-beta pathway into the cellular signalling network. Cell Signal. 2002;14:977–988. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00058-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]