Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the U.S. and worldwide. Sex-related disparities have been identified in the presentation and incidence rate of CVD. Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a role in both the etiology and pathology of CVD. Recent work has suggested that the sex hormones play a role in regulating mitochondrial dynamics, metabolism, and cross talk with other organelles. Specifically, the female sex hormone, estrogen, has both a direct and an indirect role in regulating mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC-1α, dynamics through Opa1, Mfn1, Mfn2, and Drp1, as well as metabolism and redox signaling through the antioxidant response element. Furthermore, data suggests that testosterone is cardioprotective in males and may regulate mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α and dynamics via Mfn1 and Drp1. These cell-signaling hubs are essential in maintaining mitochondrial integrity and cell viability, ultimately impacting CVD survival. PGC-1α also plays a crucial role in inter-organellar cross talk between the mitochondria and other organelles such as the peroxisome. This inter-organellar signaling is an avenue for ameliorating rampant ROS produced by dysregulated mitochondria and for regulating intrinsic apoptosis by modulating intracellular Ca2+ levels through interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. There is a need for future research on the regulatory role of the sex hormones, particularly testosterone, and their cardioprotective effects. This review hopes to highlight the regulatory role of sex hormones on mitochondrial signaling and their function in the underlying disparities between men and women in CVD.

Keywords: sexual dimorphism, cardiovascular disease, estrogen, testosterone, mitochondria

Cardiovascular Disease and Sex Steroid Signaling

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is modulated by mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium handling, aging, etc., which are reviewed in detail in the corresponding reviews (Khoury et al., 1992; Sandstede et al., 2000; Berridge, 2003; Lou et al., 2012; Keller and Howlett, 2016; Ventura-Clapier et al., 2017; Virani et al., 2020). Sex disparities in the cardiovascular system including heart size, body size, adipose deposition, etc. have been linked to variations in CVD risk and rates. In this review, we will focus on sex hormone driven differences in CVD. In general, women express higher levels of estrogen and estrogen receptors (ERs) than men, while men express higher levels of testosterone and androgen receptors (ARs) than women; as both sexes age, there is a decrease in the predominant sex hormone. While the primary sex hormone decreases, there is a concurrent increase in estrogen in men and an increased ratio of testosterone to estrogen in women (Araujo and Wittert, 2011; Bowling et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2018).

Currently, there are conflicting results on the role of testosterone in CVD, but it is documented that the decrease in testosterone in men with age and the higher ratio of testosterone to estrogen in post-menopausal women may be linked to increased CVD incidence (Freeman et al., 2010; Elagizi et al., 2018). Human studies have shown confounding results regarding the cardioprotective effects of menopausal hormone therapy to increase estrogen levels in women during the post-menopausal period (Stampfer et al., 1991; Rossouw et al., 2002; Hodis and Mack, 2014). The stark decrease in estrogen levels in the post-menopausal period have also been linked to obesity and metabolic syndrome incidence (Araujo and Wittert, 2011; Ziaei and Mohseni, 2013; Bowling et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018; Terrazas et al., 2019). The sex hormones also regulate differences in metabolism, specifically in regards to fat accumulation and body shape between men and women, which are known modulators of CVD risk (Bjorntorp, 1997; Fui et al., 2014; Mercado et al., 2015; Van Pelt et al., 2015; Leeners et al., 2017; Terrazas et al., 2019). The metabolic differences associated with changes in hormone status—which are influenced by a plethora of factors including sex chromosomes, gene expression and regulation, and epigenetics—are key to understanding CVD disparities between men and women (Ventura-Clapier et al., 2019). This review will focus on sex hormone signaling and its potential cardioprotective effects, discuss controversial findings regarding sex hormone signaling, and highlight the need for further research to create efficacious and sex-specific CVD treatments.

To elucidate the roles of estrogen and testosterone in CVD, it is essential to understand the roles of their associated receptors, including estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), G protein coupled estrogen receptor (GPER/GCPR30), and ARs. The regulation of estrogen and androgen receptor expression is challenging to study, as they are sex-, age-, cell type-, and organelle-specific (Lizotte et al., 2009; Dart et al., 2013; Bowling et al., 2014; Hutson et al., 2019). At the cellular level, it has been shown that varying cell types express different levels of sex hormone receptors, highlighting that each organ system may have differential sexual dimorphic regulation (Erlandsson et al., 2001; Deroo and Korach, 2006; Levin, 2009; Dart et al., 2013; Mahmoodzadeh and Dworatzek, 2019; Ventura-Clapier et al., 2019). Within the cell, sex hormone receptors can be found in a variety of locations including the cell membrane, nucleus, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum, although, again, these locations vary depending upon the cell type (Levin, 2009; Lizotte et al., 2009; Luo and Kim, 2016; Pedernera et al., 2017). In cardiomyocytes, the hormone receptors are expressed at different locations on various organelles; for example, both ERα and ERβ have been found to be localized to the mitochondria, while GPER has been localized to both the cell membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum (Lizotte et al., 2009; Luo and Kim, 2016; Zimmerman et al., 2016; Pedernera et al., 2017; Gourdy et al., 2018; Ventura-Clapier et al., 2019). While receptor expression within the cardiovascular system is known, further studies understanding how the ERs and ARs change based on age and hormone status is needed.

The mitochondrion plays an integral role in the production of the steroid hormones, as it is the site wherein the first step of sex hormone synthesis occurs (Miller, 2013). These same sex hormones are implicated in regulating mitochondrial dynamics and function. Cholesterol is the building block for the steroid hormones, specifically the C27-steroid cholesterol, which enters the mitochondria through the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein where the cytochrome P450 enzyme, CYP11A1, produces pregnenolone; pregnenolone can subsequently be transported back into the cytosol and converted, through a series of enzymatic steps, into either estrogen (estradiol) or testosterone (Hu et al., 2010; Miller and Bose, 2011; Samavat and Kurzer, 2015). The enzyme aromatase converts testosterone into estradiol, and recent studies have found elevated aromatase correlates with metabolic dysfunction in women (Araujo and Wittert, 2011; Iyengar et al., 2017). It has also been shown that adipose tissue is the primary producer of estrogen in post-menopausal women, adding to the complexity of estrogen signaling (Cleland et al., 1985; Chen and Madak-Erdogan, 2018). The differences in serum estrogen and testosterone levels can greatly influence cellular processes and adipose deposition, which can modulate CVD risk.

Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone activate the nuclear AR, which regulates transcription of genes located near androgen response elements or via a DNA binding independent pathway to activate ERK, Akt, and MAPK pathways (Benten et al., 1999b; Davey and Grossmann, 2016). Plasma membrane associated ARs play an important role in calcium (Ca2+) signaling, in addition to influencing endoplasmic reticulum signaling and apoptosis (Benten et al., 1999a,b; Segawa et al., 2002; Davey and Grossmann, 2016; Azhary et al., 2018). AR and androgen hormones are also essential for the development and normal physiology of the cardiovascular system (Ikeda et al., 2005). In comparison, the classical pathway of ERα activation involves its association with heat shock proteins within the cytosol; once estrogen binds ERα and/or ERβ, they can dimerize and translocate to the nucleus to activate transcription via the estrogen response element (Levin, 2009). ERα has also been shown to induce signaling cascades —including Akt, PKA and ERK1/2, and eNOS— through a membrane-initiated sequence whereby a post-translationally modified pool of ERα is localized near the plasma membrane due to an interaction with caveolin 1 (Levin, 2009; Yasar et al., 2017). After estrogen binds the receptor, it induces additional signaling pathways. ERα and ERβ are found on the plasma membrane, as both homo- and heterodimers, and expression is differential based on cell type, as previously mentioned (Li L. et al., 2003; Levin, 2009; Bowling et al., 2014). ERβ has been shown to localize to the mitochondria in cardiomyocytes of both humans and rodents, and has been proposed to play a role in mitochondrial integrity (Yang et al., 2004). GPER, a membrane-bound estrogen receptor, induces cAMP, IP3, Ca2+, and the MAPK/ERK pathways (Aronica et al., 1994; Improta-Brears et al., 1999; Filardo et al., 2000). Unlike ERα and ERβ expression, which are strictly regulated by estrogen levels and decrease in the post-menopausal period, GPER levels appear to be unaffected by circulating estrogen levels induced by menopause, but may fluctuate with estrous cycle (Cheng et al., 2014; Zimmerman et al., 2016). Data also suggests that GPER activation is protective after a vascular injury in ERα and ERβ KO mice, and can regulate mitochondrial function and biogenesis in ovariectomized mice (Bowling et al., 2014; Sbert-Roig et al., 2016; Mahmoodzadeh and Dworatzek, 2019). Therefore, more research is needed to determine the expression and role of GPER in preventing CVD injury.

Cellular Metabolism

Mitochondria play a crucial role in many molecular pathways and cellular bioenergetics. Mitochondria comprise about 35% of the entire cell volume in cardiomyocytes, making their function even more crucial to proper cardiovascular function (Dedkova and Blatter, 2012; Consolini et al., 2017). The mitochondrion contains its own small genome, encoding 37 mitochondrial proteins which are translated in the mitochondria, while the remaining proteins and RNAs are encoded by the nuclear genome (Lee and Han, 2017). Since the majority of mitochondrial proteins arise from nuclear transcription, cross talk between the mitochondria and the nucleus is imperative for effective metabolism and function. Mitochondrial proteins and their precursors are transported from cytosolic ribosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum into the mitochondria and then integrated with mitochondrially-derived proteins via sorting, assembly, and importing machinery (Pfanner and Meijer, 1997; Ellenrieder et al., 2015, 2017; Doan et al., 2020). This, in conjunction with the formation of phospholipid precursors by the endoplasmic reticulum for the mitochondria, such as cardiolipin, shows the importance of cross communication for proper mitochondrial function, as well as modulation by hormones (Ellenrieder et al., 2017; Pozdniakova et al., 2018; Acaz-Fonseca et al., 2020).

Mitochondria utilize a variety of energy sources including glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids to produce reducing equivalents for mitochondrial respiration and ATP production, which is essential in cardiac tissue. Developing cardiomyocytes prefer glucose as their energy source, whereas adult cardiomyocytes prefer fatty acids; recent studies suggest that alteration of energy sources in cardiomyocyte metabolism can contribute to CVD progression (Piquereau et al., 2010, 2012; Krzywanski et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2014; Siasos et al., 2018). Mitochondrial metabolism produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are increased in mitochondrial dysfunction and prevalent in CVD (Wang and Zou, 2018). To reduce ROS, antioxidant proteins, including superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), SOD2, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) can be upregulated (Table 1). In the heart, estrogen and testosterone have been shown to increase these antioxidant enzymes, and may act in a cardioprotective manner (Barp et al., 2002; Strehlow et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Liu H. et al., 2014; Liu Z. et al., 2014; Redmann et al., 2014; Pozdniakova et al., 2018; Mahmoodzadeh and Dworatzek, 2019; Ventura-Clapier et al., 2019; Asmis and Giordano-Mooga, 2020; Casin and Kohr, 2020). In the vasculature, GPER has been shown to modulate ROS through downregulation of oxidative stress proteins such as NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4), Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), and GPx1 in addition to upregulating antioxidant proteins such as SIRT3 and GSTK1 (Wang H. et al., 2018; Ogola et al., 2019). Additionally, it has been shown that GPER downregulates an essential autophagy protein light chain 3—LC3I/LC3II—via upregulation of PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1), and a concurrent decrease in mitochondrial parkin localization indicating a decrease in mitophagy (Feng et al., 2017). GPER activation, through mitochondrial and lysosomal cross talk mechanisms, is an important mitigator of ROS in CVD (Lee et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2017). These same antioxidant proteins have been associated with peroxisomal function and are key players in the peroxisome’s regulation of intracellular ROS levels (Schrader and Fahimi, 2006; Wang Q. et al., 2015). Because ROS regulation is critical in metabolic homeostasis and mitochondrial dynamics, perturbation of these processes often leads to increased risk of pathological outcomes, such as CVD (Krzywanski et al., 2011; Siasos et al., 2018). Hence, understanding how mitochondrial dynamics and cross talk are impacted by ROS and modulated by sex hormones is critical in elucidating the mechanisms underlying CVD.

TABLE 1.

Impact of sex hormones on cardiac cell protein expression.

| Protein/channel | Model | Testosterone (including DHT) regulation | Estrogen (including estradiol, estrone, and estrogen) regulation |

| ERα | (Lizotte et al., 2009) CD1 mice | Timing specific regulation | |

| (Park et al., 2017) Human skeletal muscle | Upregulated | ||

| (Bowling et al., 2014) ERα KO and WT mice | Regulates expression | ||

| ERβ | (Lizotte et al., 2009) CD1 mice | No regulation | |

| (Park et al., 2017) Human skeletal muscle | Upregulated | ||

| (Bowling et al., 2014) ERβ KO and WT mice | Regulates expression | ||

| GPER | (Wang H. et al., 2018) GPER-KO mice | ||

| AR | (Lizotte et al., 2009; Pedernera et al., 2017) CD1 mice | ||

| (Kerkhofs et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2016) ARKO and ARKI mice | |||

| (Hanke et al., 2001) Rabbit aorta | Upregulation | ||

| (Dart et al., 2013) ARE-Luc knock-in mice | Upregulation | No regulation | |

| (Marsh James et al., 1998) Rat cardiomyocytes | Upregulation | No regulation | |

| Unspecified SOD | (Zhang et al., 2011) Tfm mice | Upregulated | Upregulated |

| (Barp et al., 2002) Wistar rats | Upregulated | ||

| (Cruz-Topete et al., 2020) Mice cardiomyocytes | Upregulated | ||

| SOD1 | (Strehlow et al., 2003) Rat VSMCs | Upregulated | |

| SOD2 | (Strehlow et al., 2003) Rat VSMCs | Upregulated | |

| (Lone et al., 2017) MCF-7 | Upregulated | ||

| (Liu Z. et al., 2014) HAECs | Upregulated | ||

| (Liu H. et al., 2014) Rat cardiomyocytes | Increased activity | ||

| GPx | (Zhang et al., 2011) Tfm mice | Upregulated | |

| (Cruz-Topete et al., 2020) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Upregulated | ||

| nNOS | (Casin and Kohr, 2020) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Upregulated | |

| eNOS | (Casin and Kohr, 2020) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Upregulated | |

| NOX4 | (Wang H. et al., 2018) GPER-KO mice | Downregulated | |

| (Cruz-Topete et al., 2020) Human sex studies | Inconclusive | Inconclusive | |

| (Ogola et al., 2019) VSMCs GPER-KO mice | Downregulated | ||

| PTGS2 | (Wang H. et al., 2018) GPER-KO mice | Downregulated | |

| SIRT3 | (Lone et al., 2017) MCF-7 | Upregulated | |

| (Wang H. et al., 2018) GPER-KO mice | Upregulated | ||

| GSTK1 | (Wang H. et al., 2018) GPER-KO mice | Upregulated | |

| K+ATP Channel | (Sakamoto and Kurokawa, 2019) Rat cardiomyocytes | Opens channels during reperfusion, cardioprotective | Opens channels during reperfusion, cardioprotective |

| (Gao et al., 2014) SUR2KO mice | Regulated, cardioprotective | ||

| (Er et al., 2004) Sprague-Dawley rats cardiomyocytes | Activated, cardioprotective | ||

| (Ballantyne et al., 2013) H9c2 cells | Upregulates expression | Upregulates expression | |

| SERCA | (Witayavanitkul et al., 2013) ORX mice cardiomyocytes | Increases activation | |

| (Hill and Muldrew, 2014) Upregulates expression | |||

| PGC-1α | (Witt et al., 2008) AC16 cell line | Upregulation | |

| (Klinge, 2008) MCF-7 and H1793 cell lines | Upregulation via NRF-1 | ||

| (Klinge, 2008) Mouse cardiac tissue | Upregulation | ||

| (Park et al., 2017) Human skeletal muscle | Upregulation | ||

| (Wang F. et al., 2015) Wistar rat cardiomyocytes | Upregulates via AMPK | ||

| Drp1 | (Martin et al., 2014) PGC-1α and PGC-1β DKO mice | Upregulated* | |

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MDA-MB-231 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) T47D cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MCF-7 cells | No Effect | ||

| (Capllonch-Amer et al., 2014) 3T3-L1 adipocytes | Downregulated | Upregulated | |

| (Lee et al., 2020) jLNCaP Cells | Upregulated | ||

| Mfn1 | (Martin et al., 2014) PGC-1α and PGC-1β DKO mice | Upregulated* | |

| (Papanicolaou et al., 2012) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Upregulated* | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MDA-MB-231 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) T47D cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MCF-7 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Capllonch-Amer et al., 2014)3T3-L1 adipocytes | Upregulated | No Effect | |

| (Lee et al., 2020) LNCaP cells | No Effect | ||

| Mfn2 | (Martin et al., 2014)PGC-1α and PGC-1β DKO mice | Upregulated* | |

| (Papanicolaou et al., 2012) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Upregulated* | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MDA-MB-231 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) T47D cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MCF-7 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Lee et al., 2020) LNCaP cells | No Effect | ||

| Opa1 | (Martin et al., 2014) PGC-1α and PGC-1β DKO mice | Upregulated* | |

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MDA-MB-231 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) T47D cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MCF-7 cells | Upregulated | ||

| (Capllonch-Amer et al., 2014) 3T3-L1 adipocytes | No Effect | Upregulated | |

| (Lee et al., 2020) LNCaP cells | No Effect | ||

| Fis1 | (Martin et al., 2014) PGC-1α and PGC-1β DKO mice | Upregulated* | |

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) MDA-MB-231 cells | No effect | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013) T47D cells | No effect | ||

| (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013)MCF-7 cells | Downregulated | ||

| (Capllonch-Amer et al., 2014) 3T3-L1 adipocytes | Downregulated | No effect | |

| (Lee et al., 2020) LNCaP cells | No effect | ||

| PINK1 | (Feng et al., 2017) Sprague–Dawley rats | Upregulated | |

| LC3I/LC3II | (Feng et al., 2017) Sprague–Dawley rats | Downregulated | |

| (Papanicolaou et al., 2012) Mouse cardiomyocytes | Downregulated* |

Summary of estrogen and testosterone regulation of antioxidant proteins, mitochondrial dynamics, intracellular Ca2+, and inter-organellar cross talk, both directly and indirectly.*Proteins indirectly regulated by the sex hormones via PGC-1α.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Dynamics

Under normal conditions, mitochondrial turnover in the adult heart occurs every 2 weeks (Dorn et al., 2015). Mitochondrial dynamics is the process of mitochondrial growth and division designed to maintain homeostasis by utilizing the fission, fusion, mitophagy, and recycling processes during growth and development as well as under environmental stressors such as ischemia, hypoxia, or oxidative stress (Dorn et al., 2015; Dorn, 2016). Recent studies have shown that regulating mitochondrial homeostasis is crucial in mitigating CVD disruption of these processes which has been previously to worse pathological outcomes or increased death (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010; Sun et al., 2013; Redmann et al., 2014). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) is a transcriptional coactivator protein crucial for maintaining homeostasis of this organelle by targeting genes involved in electron transport chain (ETC) and apoptotic signaling (Liang and Ward, 2006; Lai et al., 2008; Wang F. et al., 2015). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an upstream regulator of PGC-1α involved in energy homeostasis and mitochondrial biogenesis and has been shown to be regulated through the sex hormones (Jornayvaz and Shulman, 2010; Varanita et al., 2015; Wang F. et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017; Hevener et al., 2020). In cardiomyocytes, activated estrogen receptors found on the cell membrane can upregulate PGC-1α activity, thereby regulating ATP synthesis, substrate oxidation, and phosphate transfer (Klinge, 2008; Witt et al., 2008). PGC-1α can also target genes that regulate metabolism in the heart, such as estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα), which protects against stressors of CVD (Huss et al., 2004; Martin et al., 2014; Li H. et al., 2015). While estrogen does not directly bind to ERRα, it activates genes regulated to mitochondrial biogenesis, and further studies are needed to understand the sexually dimorphic regulation (Horard and Vanacker, 2003). These data indicate a crucial signaling role for estrogen in the maintenance of mitochondria.

Estrogen has also been shown to activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a partner of PGC-1α, which functions to transcriptionally regulate fatty acid metabolism in the heart. Activation of PPARα induces the expression of Pex genes leading to peroxisomal biogenesis, while simultaneously inducing the expression of mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins mitofusin 1 (Mfn1), mitofusin 2 (Mfn2), dynamin-related protein-1 (Drp1), and fission protein 1 (Fis1) (Table 1; Bagattin et al., 2010; Papanicolaou et al., 2012; Schrader et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2014; Varanita et al., 2015). Increased number of peroxisomes in conjunction with sustained mitochondrial integrity increases β-oxidation of long chain fatty acids and fatty acid-induced cellular respiration. It has been further suggested that these tissues upregulate PGC-1α in response to increased lipid intake, acting as a compensatory mechanism for high fat diets and metabolic dysregulation. This co-regulation of peroxisomal and mitochondrial biogenesis has been established in brown adipose tissue, liver and skeletal muscle (Huang et al., 2017, 2019; Hevener et al., 2020). Work has yet to be done showing the proliferation of peroxisomes in cardiac tissue, but findings in other tissues is highly suggestive of the need for future research in this area.

PPARα KO mice have severely impaired cardiac function due to lipid accumulation and hypoglycemia which causes death in all males but only 25% of females; however, pretreatment of β-estradiol in males with ablated PPARα survived, implicating estrogen signaling as a crucial mechanism for cardiac metabolism (Nöhammer et al., 2003). Estrogen plays a crucial role in cardiac lipid metabolism for both males and females in vivo (Djouadi et al., 1998). This data, again, highlights the importance of estrogen signaling in cardiac metabolism.

Many cardiovascular pathologies have notable alterations in mitochondrial network morphology. Mitochondrial fission is a process by which mitochondria alter their physical structure; symmetrical division for replication or asymmetrical division to remove damaged organelle components (Shirihai et al., 2015). Asymmetrical fission acts as quality control for damaged mitochondria resulting in fragmentation, which can be utilized for selective mitophagy (Ong et al., 2010; Shirihai et al., 2015). While both processes serve as protective mechanisms for cellular damage and apoptosis through the mitochondria, the mechanisms of activation via other cellular organelles are different. In mitochondrial fusion, the mitochondria fuse with other organelles to repair and regenerate, as opposed to mitochondrial fission, where DNA replication is upregulated in response to mitochondrial damage, inhibiting cytochrome c release and corresponding apoptosis (Chen et al., 2012; Varanita et al., 2015; Dorn, 2016; Hevener et al., 2020). Major proteins associated with fission and fusion include Drp1, Fis1, Mfn1 and Mfn2, and the optic atrophy-1 protein (Opa1). Drp1 is recruited to the outer mitochondrial matrix (OMM) and has been shown to interact with the endoplasmic reticulum, highlighting the importance of inter-organellar cross talk during mitochondrial fission events (Ishihara et al., 2009). Mfn1 and 2 are responsible for fusing OMMs and tethering the mitochondria to the SR for Ca2+ signaling, making mitofusin proteins indispensable to inter-molecular and inter-organellar interactions (Chen et al., 2012). These proteins also have an important role in mitochondrial quality control by mediating fusion, guiding protein folding, and preventing ROS-induced mitophagy (Shirihai et al., 2015; Song et al., 2015). Opa1 mediates inner mitochondrial membrane fusion and maintains cristae structure, which ensures proper ETC function (Varanita et al., 2015). This increase in cristae integrity can reduce ROS and prevent cytochrome c release, preventing and reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in highly-metabolic tissues, like the heart and brain (Ong et al., 2010; Varanita et al., 2015).

Abnormal fission and fusion leading to reduced cristae integrity and less functionally efficient morphology—overtly spherical or elongated—are known contributors to heart failure due to their effects on metabolism and apoptosis (Ong et al., 2010; Papanicolaou et al., 2012; Dorn, 2016). Mitochondrial fission opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) which can result in cell necrosis or mitophagy if not properly managed, as seen in ischemic conditions (Parra et al., 2008; Shirihai et al., 2015; Song et al., 2015). Activation of GPER and ERα has been shown to preserve mitochondrial function and decrease mitophagy after ischemia reperfusion injury via MPTP signaling through MEK/ERK activation, thereby decreasing apoptosis (Feng et al., 2017; Mahmoodzadeh and Dworatzek, 2019). These data, again, suggest the estrogen has cardioprotective effects by preserving mitochondrial integrity and inhibiting apoptosis. Testosterone has also been shown to protect against myocardial infarction through the AMPK pathway, elevating PGC-1α and preserving mitochondrial integrity leading to decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis, as demonstrated by rodent models (Witt et al., 2008; Wang F. et al., 2015). The ability of both estrogen and testosterone to activate PGC-1α in cardiac tissue has been extensively studied, and it is well-established that PGC-1α regulates the transcription of Drp1, Fis1, Mfn1, Mfn2, Opa1, and other important mitochondrial dynamic proteins (Table 1; Witt et al., 2008; Papanicolaou et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2014; Wang F. et al., 2015; Park et al., 2017). This therefore implies a potentially shared pathway for cardioprotection by estrogen and testosterone, but direct evidence has remained elusive. Adding to the complexity, direct regulation of mitochondrial dynamics by the sex hormones has been well established in brain, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and adipocyte models but more research is needed to better characterize the direct effects of estrogen and testosterone in modulating signaling in cardiac tissue as well as inter-organellar cross talk between the mitochondria and other cellular organelles (Sastre-Serra et al., 2013; Capllonch-Amer et al., 2014; Lejri et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020).

Sarcoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondrial Cross Talk

The KATP channel, found on both the mitochondria and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), alters the electrochemical gradient through an influx of K+ into each organelle (Ranki et al., 2002; Er et al., 2004; Ballantyne et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2014; Bayat et al., 2016; Sakamoto and Kurokawa, 2019). In the mitochondrion, this change in K+ concentration causes an increase in K+/H+ antiporter activity, inducing an efflux of H+ ions from the mitochondrial intermembranous space. The resulting decreased membrane potential impairs organelle efficiency and reduces mitochondrial production of ATP. The activation of the KATP channel by both estrogen and testosterone has been shown to be cardioprotective in models of ischemia reperfusion injury (Er et al., 2004; Ballantyne et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2014; Sakamoto and Kurokawa, 2019). Estrogen, but not testosterone, can also regulate the SR KATP channel, which has also been shown to preserve cardiac function after ischemia reperfusion injury (Ranki et al., 2002). Evidence further suggests that testosterone may have a down-regulation effect on SR KATP channels in exercise models, suggesting a potentially antithetical effect from estrogen (Bayat et al., 2016). GPER activation has also been indicated as a possible mitigator of cell death during reperfusion injury through modulation of mitochondrial integrity, further supporting estrogen’s cardioprotective properties (Lee et al., 2012; Feng et al., 2017; Groban et al., 2019). Taken together, these data suggest potential mechanisms of cardioprotection via sex hormone regulation of KATP channels on mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticula.

Another important ion to consider in this interorganellar crosstalk is calcium (Ca2+). Ca2+ is a divalent ion, and an essential mineral vital for cellular signaling, which has been a critical area of study for several decades (Berridge, 2003; Brookes et al., 2004; Clapham, 2007). Calcium signaling has also been extensively studied in the mitochondrion and plays important roles in the regulation of many enzymes in the Krebs cycle, electron transport complexes such as ATP synthase, as well as many other enzymes (Das and Harris, 1990; McCormack et al., 1990; Consolini et al., 2017). In cardiomyocytes, an essential mechanism of cardiac function is the maintenance of high levels of ATP in order to properly activate SERCA—a Ca2+ pump on the surface of the sarcoplasmic reticulum—and induce the reloading of Ca2+ in action potentials (Rosano et al., 1999; Piquereau et al., 2010; Witayavanitkul et al., 2013). Modulation of SERCA levels or activity and Ca2+ burden by testosterone is suggested to be cardioprotective during ischemic events (Witayavanitkul et al., 2013). Additionally, it has been shown that estrogen can increase SERCA protein expression, particularly SERCA2b, which causes a decrease in intracellular Ca2+, thus increasing cell survival in coronary arteries (Witayavanitkul et al., 2013; Hill and Muldrew, 2014; Groban et al., 2019).

In cardiomycocytes, move phrase to after (CICR), the primary driver of Ca2+ release is through Ca2+ induced Ca2+ release (CICR). One example of a channel which exists in the inner mitochondrial membranes and the SR are the ryanodine receptors (RyR/mRyR), which are responsible for releasing intracellular stores of Ca2+ ions through CICR (Beutner et al., 2005; Altschafl et al., 2007; Gambardella et al., 2018). Leaky RyR on the SR has been directly implicated in heart failure, as excess cytosolic calcium is absorbed by mitochondria resulting in dysregulation and further RyR leak from oxidative damage generated by mitochondrial ROS (Santulli et al., 2015). In contrast, when Ca2+ is released from inositol-triphosphate receptors (IP3R)—receptors responsible for Ca2+ release and a mechanism for triggering CICR—and absorbed by mitochondria, whose function, mitochondria or IP3R and ATP production increases; however, when mitochondria number is compromised—such as in heart failure, the Ca2+ release can induce arrhythmias (Hohendanner et al., 2015; Seidlmayer et al., 2016). The effect of estrogen on RyR expression and function is mixed and poorly understood, whereas growing evidence is implicating testosterone in increasing expression and function (Tsang et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2015; Evanson et al., 2018; Groban et al., 2019; Mahmoodzadeh and Dworatzek, 2019; Jiao et al., 2020). For IP3R, the role of estrogens is even more poorly understood, with some work implicating estrogen’s ability to activate IP3 production in liver and smooth muscle cells, whereas testosterone has been shown to directly trigger IP3 production and IP3R activation in cardiomyocytes (Marino et al., 1998; Vicencio et al., 2006). In summary, these data suggest that the sex hormones play an important role in regulating intracellular Ca2+, itself a regulator of cellular apoptosis through the mitochondrion, thereby highlighting an additional cardioprotective role of the sex hormones (Pinton et al., 2008; Groban et al., 2019).

Cell Death

There is conflicting information regarding the role of the sex hormones in regulating cell death in cardiac tissue, and therefore, indicated a need for further research in this area (Djouadi et al., 1998; Morris and Channer, 2012; Hsieh et al., 2015; Wang F. et al., 2015; Gagliano-Juca and Basaria, 2018; Jones and Kelly, 2018). Cell death pathways, including apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis, and pyroptosis, have been implicated in inducing cell death in CVD among various cell types within the heart including cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and monocytes/macrophages (Subramanian and Shaha, 2007; Wang F. et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2017; Amgalan et al., 2020; Di Florio et al., 2020). In macrophages, estrogen has been shown to regulate intracellular Ca2+ levels, which modulates Bcl-2 activity, and decreases Bax translocation to the mitochondria, thereby preserving cell viability through inhibition of intrinsic apoptosis (Subramanian and Shaha, 2007). Preliminary data in cardiomyocytes has shown that estrogen regulates Akt through ERα which attenuates ROS-induced intrinsic apoptosis in female mice, but not males (Wang F. et al., 2010; Hevener et al., 2020). While the previous study determined ERβ does not play an anti-apoptotic role in response to ROS, estrogen signaling through ERβ has been shown to decrease cardiac apoptosis by increasing mitochondrial Complex IV in rodent trauma-hemorrhage models (Hsieh et al., 2006). However, more recent studies have indicated that ERβ is not highly expressed on cardiomyocytes, and therefore may not play a major cardioprotective role in CVD (Pugach et al., 2016; Groban et al., 2019).

Testosterone has been shown to indirectly regulate necrosis of cardiomyocytes through NF-κB apoptotic signaling pathways, however, more studies on the regulation of cell death by testosterone are essential to better understand its role in CVD (Xiao et al., 2015). Estrogen and testosterone’s roles in apoptosis may be altered according to receptor expression and cell type (Pugach et al., 2016). Therefore, further studies are necessary to better understand how signaling via both estrogen and testosterone influence cardiac apoptosis in CVD. Necrosis and pyroptosis are inflammatory cell death pathways regulated via caspase enzyme activity, which is induced when irreversible damage occurs in the tissues (Bergsbaken et al., 2009; Gao et al., 2019; Zhaolin et al., 2019). These pathways, more specifically, are initiated when the MPTP is damaged or uncontrolled in mitochondrial fission, as seen in CVD (Song et al., 2015; Amgalan et al., 2020). Estrogen treatment has been shown to inhibit necrosis and induce apoptosis in both sexes with lupus nephritis (Jog and Caricchio, 2013). In general, research on pyroptosis is limited in cardiac tissue and work has yet to indicate a direct role of the sex hormones.

Conclusion

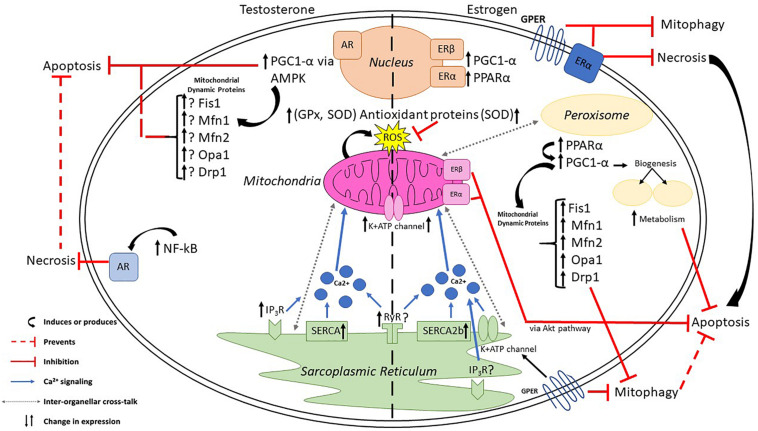

There are clinical disparities in CVD risk and incidence, which could be caused by known sexually dimorphic differences in cardiac cells and tissues. These differences are driven by the sex hormones—estrogen and testosterone—and the presence of their receptors ERα, ERβ, GPER and AR, which are expressed differentially in varying organ systems and cell types. Studies have shown that both estrogen and testosterone can directly regulate mitochondrial biogenesis, ROS production, inter-organellar interactions between the mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum, in addition to preserving cell viability (Figure 1). Nevertheless, further studies are needed to better understand the exact mechanism of each sex hormone in regulating mitochondrial dynamics, specifically the regulation of mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins, so to establish differential function of each and elucidating the cause of CVD disparities between the sexes. Research on the cardioprotective effects of sex hormones has predominantly focused on estrogen, leaving much to be studied regarding testosterone’s regulatory function in CVD. This review hopes to inspire others to begin focusing on the regulatory role of sex hormones in mitochondrial function and dynamics, as well as inter-organellar cross talk.

FIGURE 1.

Estrogen and testosterone influence mitochondrial dynamics and cross talk between organelles. Estrogen, via PPARα, upregulates PGC-1α to initiate transcription of mitochondrial dynamic proteins and induce peroxisomal biogenesis. Testosterone upregulates PGC-1α, via AMPK, to influence mitochondrial dynamics. Both sex hormones increase antioxidant proteins to mitigate damaging reactive oxygen species, regulate Ca2+ signaling via K+ATP channels on the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and prevent various forms of cell death in CVD including apoptosis, necrosis, and mitophagy.

Author Contributions

SL wrote the mitochondrial dynamics section and metabolism, edited the manuscript, and created the Figure 1. JB wrote the section on cell death and Ca2+ regulation, created the Table 1, and reviewed the manuscript. MS compiled the sources for metabolism and dynamics, reviewed the manuscript, table, and figure. SG-M wrote the introduction and conclusion, edited the text, figures and table, and reviewed the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. MRS Co-wrote metabolism and Ca2+ sections, edited text, and reviewed the manuscript, table, and figure.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by The Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences Program in the School of Health Professions.

References

- Acaz-Fonseca E., Ortiz-Rodriguez A., Garcia-Segura L. M., Astiz M. (2020). Sex differences and gonadal hormone regulation of brain cardiolipin, a key mitochondrial phospholipid. J. Neuroendocrinol. 32:e12774. 10.1111/jne.12774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschafl B. A., Beutner G., Sharma V. K., Sheu S. S., Valdivia H. H. (2007). The mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in rat heart: a pharmaco-kinetic profile. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768 1784–1795. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amgalan D., Garner T. P., Pekson R., Jia X. F., Yanamandala M., Paulino V., et al. (2020). A small-molecule allosteric inhibitor of BAX protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Nat. Cancer 1 315–328. 10.1038/s43018-020-0039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo A. B., Wittert G. A. (2011). Endocrinology of the aging male. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 25 303–319. 10.1016/j.beem.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica S. M., Kraus W. L., Katzenellenbogen B. S. (1994). Estrogen action via the cAMP signaling pathway: stimulation of adenylate cyclase and cAMP-regulated gene transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 8517–8521. 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmis R., Giordano-Mooga S. (2020). Sexual dimorphisms in redox biology. Redox Biol. 31:101533. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhary J. M. K., Harada M., Takahashi N., Nose E., Kunitomi C., Koike H., et al. (2018). Endoplasmic reticulum stress activated by androgen enhances apoptosis of granulosa cells via induction of death receptor 5 in PCOS. Endocrinology 160 119–132. 10.1210/en.2018-00675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagattin A., Hugendubler L., Mueller E. (2010). Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha promotes peroxisomal remodeling and biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 20376–20381. 10.1073/pnas.1009176107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne T., Du Q., Jovanović S., Neemo A., Holmes R., Sinha S., et al. (2013). Testosterone protects female embryonic heart H9c2 cells against severe metabolic stress by activating estrogen receptors and up-regulating IES SUR2B. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45 283–291. 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barp J., Araujo A. S., Fernandes T. R., Rigatto K. V., Llesuy S., Bello-Klein A., et al. (2002). Myocardial antioxidant and oxidative stress changes due to sex hormones. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 35 1075–1081. 10.1590/s0100-879x2002000900008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat G., Javan M., Safari F., Khalili A., Shokri S., Goudarzvand M., et al. (2016). Nandrolone decanoate negatively reverses the beneficial effects of exercise on cardiac muscle via sarcolemmal, but not mitochondrial K(ATP) channel. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 94 324–331. 10.1139/cjpp-2015-0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten W. P., Lieberherr M., Giese G., Wrehlke C., Stamm O., Sekeris C. E., et al. (1999a). Functional testosterone receptors in plasma membranes of T cells. FASEB J. 13 123–133. 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten W. P., Lieberherr M., Stamm O., Wrehlke C., Guo Z., Wunderlich F. (1999b). Testosterone signaling through internalizable surface receptors in androgen receptor-free macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell 10 3113–3123. 10.1091/mbc.10.10.3113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T., Fink S. L., Cookson B. T. (2009). Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7 99–109. 10.1038/nrmicro2070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. (2003). Cardiac calcium signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31(Pt 5), 930–933. 10.1042/bst0310930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutner G., Sharma V. K., Lin L., Ryu S. Y., Dirksen R. T., Sheu S. S. (2005). Type 1 ryanodine receptor in cardiac mitochondria: transducer of excitation-metabolism coupling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1717 1–10. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorntorp P. (1997). Body fat distribution, insulin resistance, and metabolic diseases. Nutrition 13 795–803. 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00191-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling M. R., Xing D., Kapadia A., Chen Y. F., Szalai A. J., Oparil S., et al. (2014). Estrogen effects on vascular inflammation are age dependent: role of estrogen receptors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34 1477–1485. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes P. S., Yoon Y., Robotham J. L., Anders M. W., Sheu S. S. (2004). Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287 C817–C833. 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capllonch-Amer G., Lladó I., Proenza A. M., García-Palmer F. J., Gianotti M. (2014). Opposite effects of 17-β estradiol and testosterone on mitochondrial biogenesis and adiponectin synthesis in white adipocytes. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 52 203–214. 10.1530/jme-13-0201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casin K. M., Kohr M. J. (2020). An emerging perspective on sex differences: intersecting S-nitrosothiol and aldehyde signaling in the heart. Redox Biol. 31:101441 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. B., Coon T. A., Glasser J. R., Zou C., Ellis B., Das T., et al. (2014). E3 ligase subunit Fbxo15 and PINK1 kinase regulate cardiolipin synthase 1 stability and mitochondrial function in pneumonia. Cell Rep. 7 476–487. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. L., Madak-Erdogan Z. (2018). Estrogens and female liver health. Steroids 133 38–43. 10.1016/j.steroids.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Csordas G., Jowdy C., Schneider T. G., Csordas N., Wang W., et al. (2012). Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ. Res. 111 863–875. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S. B., Dong J., Pang Y., LaRocca J., Hixon M., Thomas P., et al. (2014). Anatomical location and redistribution of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1 during the estrus cycle in mouse kidney and specific binding to estrogens but not aldosterone. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 382 950–959. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D. E. (2007). Calcium signaling. Cell 131 1047–1058. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W. H., Mendelson C. R., Simpson E. R. (1985). Effects of aging and obesity on aromatase activity of human adipose cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 60 174–177. 10.1210/jcem-60-1-174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolini A. E., Ragone M. I., Bonazzola P., Colareda G. A. (2017). Mitochondrial bioenergetics during ischemia and reperfusion. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 982 141–167. 10.1007/978-3-319-55330-6_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Topete D., Dominic P., Stokes K. Y. (2020). Uncovering sex-specific mechanisms of action of testosterone and redox balance. Redox Biol. 31:101490 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart D. A., Waxman J., Aboagye E. O., Bevan C. L. (2013). Visualising androgen receptor activity in male and female mice. PLoS One 8:e71694. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A. M., Harris D. A. (1990). Control of mitochondrial ATP synthase in heart cells: inactive to active transitions caused by beating or positive inotropic agents. Cardiovasc. Res. 24 411–417. 10.1093/cvr/24.5.411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey R. A., Grossmann M. (2016). Androgen receptor structure. Function and biology: from bench to bedside. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 37 3–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedkova E. N., Blatter L. A. (2012). Measuring mitochondrial function in intact cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 52 48–61. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroo B. J., Korach K. S. (2006). Estrogen receptors and human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 116 561–570. 10.1172/JCI27987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio D. N., Sin J., Coronado M. J., Atwal P. S., Fairweather D. (2020). Sex differences in inflammation, redox biology, mitochondria and autoimmunity. Redox Biol. 31:101482. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouadi F., Weinheimer C. J., Saffitz J. E., Pitchford C., Bastin J., Gonzalez F. J., et al. (1998). A gender-related defect in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis in peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor alpha- deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 102 1083–1091. 10.1172/JCI3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan K. N., Grevel A., Martensson C. U., Ellenrieder L., Thornton N., Wenz L. S., et al. (2020). The mitochondrial import complex MIM functions as main translocase for alpha-helical outer membrane proteins. Cell Rep. 31:107567. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn G., II (2016). Mitochondrial fission/fusion and cardiomyopathy. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 38 38–44. 10.1016/j.gde.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn G. W., II, Vega R. B., Kelly D. P. (2015). Mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in the developing and diseased heart. Genes Dev. 29 1981–1991. 10.1101/gad.269894.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elagizi A., Kohler T. S., Lavie C. J. (2018). Testosterone and cardiovascular health. Mayo Clin. Proc. 93 83–100. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenrieder L., Martensson C. U., Becker T. (2015). Biogenesis of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, problems and diseases. Biol. Chem. 396 1199–1213. 10.1515/hsz-2015-0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenrieder L., Rampelt H., Becker T. (2017). Connection of protein transport and organelle contact sites in mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 429 2148–2160. 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er F., Michels G., Gassanov N., Rivero F., Hoppe Uta C. (2004). Testosterone induces cytoprotection by activating ATP-Sensitive K+ channels in the cardiac mitochondrial inner membrane. Circulation 110 3100–3107. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146900.84943.E0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsson M. C., Ohlsson C., Gustafsson J. A., Carlsten H. (2001). Role of oestrogen receptors alpha and beta in immune organ development and in oestrogen-mediated effects on thymus. Immunology 103 17–25. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01212.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanson K. W., Goldsmith J. A., Ghosh P., Delp M. D. (2018). The G protein-coupled estrogen receptor agonist, G-1, attenuates BK channel activation in cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 6:e00409. 10.1002/prp2.409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Madungwe N. B., da Cruz Junho C. V., Bopassa J. C. (2017). Activation of G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor 1 at the onset of reperfusion protects the myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury by reducing mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174 4329–4344. 10.1111/bph.14033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo E. J., Quinn J. A., Bland K. I., Frackelton A. R., Jr. (2000). Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol. Endocrinol. 14 1649–1660. 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman E. W., Sammel M. D., Lin H., Gracia C. R. (2010). Obesity and reproductive hormone levels in the transition to menopause. Menopause 17 718–726. 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181cec85d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fui M. N., Dupuis P., Grossmann M. (2014). Lowered testosterone in male obesity: mechanisms, morbidity and management. Asian J. Androl. 16 223–231. 10.4103/1008-682X.122365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano-Juca T., Basaria S. (2018). Trials of testosterone replacement reporting cardiovascular adverse events. Asian J. Androl. 20 131–137. 10.4103/aja.aja_28_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambardella J., Trimarco B., Iaccarino G., Santulli G. (2018). New insights in cardiac calcium handling and excitation-contraction coupling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1067 373–385. 10.1007/5584_2017_106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Xu D., Sabat G., Valdivia H., Xu W., Shi N.-Q. (2014). Disrupting KATP channels diminishes the estrogen-mediated protection in female mutant mice during ischemia-reperfusion. Clin. Proteomics 11:19. 10.1186/1559-0275-11-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Zhao L., Wang J., Zhang L., Zhou D., Qu J., et al. (2019). C-Phycocyanin ameliorates mitochondrial fission and fusion dynamics in ischemic cardiomyocyte damage. Front. Pharmacol. 10:733. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourdy P., Guillaume M., Fontaine C., Adlanmerini M., Montagner A., Laurell H., et al. (2018). Estrogen receptor subcellular localization and cardiometabolism. Mol. Metab. 15 56–69. 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groban L., Tran Q. K., Ferrario C. M., Sun X., Cheng C. P., Kitzman D. W., et al. (2019). Female heart health: is GPER the missing link? Front. Endocrinol. 10:919. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke H., Lenz C., Hess B., Spindler K.-D., Weidemann W. (2001). Effect of testosterone on plaque development and androgen receptor expression in the arterial vessel wall. Circulation 103 1382–1385. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.10.1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevener A. L., Ribas V., Moore T. M., Zhou Z. (2020). The impact of skeletal muscle ERalpha on mitochondrial function and metabolic health. Endocrinology 161:bqz017 10.1210/endocr/bqz017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill B. J., Muldrew E. (2014). Oestrogen upregulates the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) ATPase pump in coronary arteries. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 41 430–436. 10.1111/1440-1681.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis H. N., Mack W. J. (2014). Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: clinical application of the timing hypothesis. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 142 68–75. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohendanner F., Walther S., Maxwell J. T., Kettlewell S., Awad S., Smith G. L., et al. (2015). Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate induced Ca2+ release and excitation-contraction coupling in atrial myocytes from normal and failing hearts. J. Physiol. 593 1459–1477. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.283226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horard B., Vanacker J. M. (2003). Estrogen receptor-related receptors: orphan receptors desperately seeking a ligand. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 31 349–357. 10.1677/jme.0.0310349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh D. J. Y., Kuo W. W., Lai Y. P., Shibu M. A., Shen C. Y., Pai P., et al. (2015). 17β-Estradiol and/or estrogen receptor β Attenuate the autophagic and apoptotic effects induced by prolonged hypoxia through HIF-1α-Mediated BNIP3 and IGFBP-3 signaling blockage. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 36 274–284. 10.1159/000374070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh Y. C., Yu H. P., Suzuki T., Choudhry M. A., Schwacha M. G., Bland K. I., et al. (2006). Upregulation of mitochondrial respiratory complex IV by estrogen receptor-beta is critical for inhibiting mitochondrial apoptotic signaling and restoring cardiac functions following trauma-hemorrhage. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 41 511–521. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu J.-C., Cheng C.-C., Kao Y.-H., Chen Y.-C., Chung C.-C., Chen Y.-J. (2015). Testosterone regulates cardiac calcium homeostasis with enhanced ryanodine receptor 2 expression through activation of TGF-β. Int. J. Cardiol. 190 11–14. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Zhang Z., Shen W. J., Azhar S. (2010). Cellular cholesterol delivery, intracellular processing and utilization for biosynthesis of steroid hormones. Nutr. Metab. 7:47. 10.1186/1743-7075-7-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-K., Lee S. O., Chang E., Pang H., Chang C. (2016). Androgen receptor (AR) in cardiovascular diseases. J. Endocrinol. 229 R1–R16. 10.1530/JOE-15-0518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T.-Y., Zheng D., Hickner R. C., Brault J. J., Cortright R. N. (2019). Peroxisomal gene and protein expression increase in response to a high-lipid challenge in human skeletal muscle. Metab. Clin. Exp. 98 53–61. 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T.-Y., Zheng D., Houmard J. A., Brault J. J., Hickner R. C., Cortright R. N. (2017). Overexpression of PGC-1α increases peroxisomal activity and mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in human primary myotubes. Am. J. Physiol. 312 E253–E263. 10.1152/ajpendo.00331.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss J. M., Torra I. P., Staels B., Giguère V., Kelly D. P. (2004). Estrogen-related receptor alpha directs peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling in the transcriptional control of energy metabolism in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Mol. Cell Biol. 24 9079–9091. 10.1128/mcb.24.20.9079-9091.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson D. D., Gurrala R., Ogola B. O., Zimmerman M. A., Mostany R., Satou R., et al. (2019). Estrogen receptor profiles across tissues from male and female Rattus norvegicus. Biol. Sex. Differ. 10:4. 10.1186/s13293-019-0219-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y., Aihara K., Sato T., Akaike M., Yoshizumi M., Suzaki Y., et al. (2005). Androgen receptor gene knockout male mice exhibit impaired cardiac growth and exacerbation of angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280 29661–29666. 10.1074/jbc.M411694200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improta-Brears T., Whorton A. R., Codazzi F., York J. D., Meyer T., McDonnell D. P. (1999). Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase requires mobilization of intracellular calcium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 4686–4691. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N., Nomura M., Jofuku A., Kato H., Suzuki S. O., Masuda K., et al. (2009). Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 is essential for embryonic development and synapse formation in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 11 958–966. 10.1038/ncb1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar N. M., Brown K. A., Zhou X. K., Gucalp A., Subbaramaiah K., Giri D. D., et al. (2017). Metabolic obesity, adipose inflammation and elevated breast aromatase in women with normal body mass index. Cancer Prev. Res. 10 235–243. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao L., Machuki J. O. A., Wu Q., Shi M., Fu L., Adekunle A. O., et al. (2020). Estrogen and calcium handling proteins: new discoveries and mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 318 H820–H829. 10.1152/ajpheart.00734.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jog N. R., Caricchio R. (2013). Differential regulation of cell death programs in males and females by Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 and 17beta estradiol. Cell Death Dis. 4:e758. 10.1038/cddis.2013.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. H., Kelly D. M. (2018). Randomized controlled trials - mechanistic studies of testosterone and the cardiovascular system. Asian J. Androl. 20 120–130. 10.4103/aja.aja_6_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jornayvaz F. R., Shulman G. I. (2010). Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Essays Biochem. 47 69–84. 10.1042/bse0470069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller K. M., Howlett S. E. (2016). Sex differences in the biology and pathology of the aging heart. Can. J. Cardiol. 32 1065–1073. 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhofs S., Denayer S., Haelens A., Claessens F. (2009). Androgen receptor knockout and knock-in mouse models. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 42 11–17. 10.1677/JME-08-0122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury S., Yarows S. A., O’Brien T. K., Sowers J. R. (1992). Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in a nonacademic setting. Effects of age and sex. Am. J. Hypertens. 5 616–623. 10.1093/ajh/5.9.616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge C. M. (2008). Estrogenic control of mitochondrial function and biogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 105 1342–1351. 10.1002/jcb.21936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywanski D. M., Moellering D. R., Fetterman J. L., Dunham-Snary K. J., Sammy M. J., Ballinger S. W. (2011). The mitochondrial paradigm for cardiovascular disease susceptibility and cellular function: a complementary concept to Mendelian genetics. Lab Invest. 91 1122–1135. 10.1038/labinvest.2011.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L., Leone T. C., Zechner C., Schaeffer P. J., Kelly S. M., Flanagan D. P., et al. (2008). Transcriptional coactivators PGC-1alpha and PGC-lbeta control overlapping programs required for perinatal maturation of the heart. Genes Dev. 22 1948–1961. 10.1101/gad.1661708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Giordano S., Zhang J. (2012). Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling. Biochem. J. 441 523–540. 10.1042/BJ20111451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. R., Han J. (2017). Mitochondrial nucleoid: shield and switch of the mitochondrial genome. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017:8060949. 10.1155/2017/8060949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. G., Nam Y., Shin K. J., Yoon S., Park W. S., Joung J. Y., et al. (2020). Androgen-induced expression of DRP1 regulates mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 471 72–87. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeners B., Geary N., Tobler P. N., Asarian L. (2017). Ovarian hormones and obesity. Hum. Reprod. Update 23 300–321. 10.1093/humupd/dmw045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejri I., Grimm A., Eckert A. (2018). Mitochondria, estrogen and female brain aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:124. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin E. R. (2009). Plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20 477–482. 10.1016/j.tem.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Liu Z., Gou Y., Yu H., Siminelakis S., Wang S., et al. (2015). Estradiol mediates vasculoprotection via ERRalpha-dependent regulation of lipid and ROS metabolism in the endothelium. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 87 92–101. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Haynes M. P., Bender J. R. (2003). Plasma membrane localization and function of the estrogen receptor alpha variant (ER46) in human endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 4807–4812. 10.1073/pnas.0831079100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Ward W. F. (2006). PGC-1alpha: a key regulator of energy metabolism. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 30 145–151. 10.1152/advan.00052.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Gou Y., Zhang H., Zuo H., Zhang H., Liu Z., et al. (2014). Estradiol improves cardiovascular function through up-regulation of SOD2 on vascular wall. Redox Biol. 3 88–99. 10.1016/j.redox.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Yanamandala M., Lee T. C., Kim J. K. (2014). Mitochondrial p38beta and manganese superoxide dismutase interaction mediated by estrogen in cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 9:e85272. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizotte E., Grandy S. A., Tremblay A., Allen B. G., Fiset C. (2009). Expression, distribution and regulation of sex steroid hormone receptors in mouse heart. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 23 075–086. 10.1159/000204096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lone M. U., Baghel K. S., Kanchan R. K., Shrivastava R., Malik S. A., Tewari B. N., et al. (2017). Physical interaction of estrogen receptor with MnSOD: implication in mitochondrial O(2)(.-) upregulation and mTORC2 potentiation in estrogen-responsive breast cancer cells. Oncogene 36 1829–1839. 10.1038/onc.2016.346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Q., Janardhan A., Efimov I. R. (2012). Remodeling of calcium handling in human heart failure. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 740 1145–1174. 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T., Kim J. K. (2016). The role of estrogen and estrogen receptors on cardiomyocytes: an overview. Can. J. Cardiol. 32 1017–1025. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodzadeh S., Dworatzek E. (2019). The role of 17beta-Estradiol and estrogen receptors in regulation of Ca(2+) channels and mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes. Front. Endocrinol. 10:310. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M., Pallottini V., Trentalance A. (1998). Estrogens cause rapid activation of IP3-PKC-alpha signal transduction pathway in HEPG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 245 254–258. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh James D., Lehmann Michael H., Ritchie Rebecca H., Gwathmey Judith K., Green Glenn E., Schiebinger Rick J. (1998). Androgen receptors mediate hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Circulation 98 256–261. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.3.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. O., Lai M. L., Soundarapandian C. M., Leone P. T., Zorzano D. A., Keller M. M., et al. (2014). A role for peroxisome proliferator-activated Receptor γ Coactivator-1 in the control of mitochondrial dynamics during postnatal cardiac growth. Circ. Res. 114 626–636. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J. G., Halestrap A. P., Denton R. M. (1990). Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 70 391–425. 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado C. I., Yang Q., Ford E. S., Gregg E., Valderrama A. L. (2015). Gender- and race-specific metabolic score and cardiovascular disease mortality in adults: a structural equation modeling approach–United States, 1988-2006. Obesity 23 1911–1919. 10.1002/oby.21171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. L. (2013). Steroid hormone synthesis in mitochondria. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 379 62–73. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. L., Bose H. S. (2011). Early steps in steroidogenesis: intracellular cholesterol trafficking. J. Lipid Res. 52 2111–2135. 10.1194/jlr.R016675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J. X., Chaudhary N., Akinyemiju T. (2017). Metabolic syndrome prevalence by race/ethnicity and sex in the United States, national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-2012. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 14:E24. 10.5888/pcd14.160287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P. D., Channer K. S. (2012). Testosterone and cardiovascular disease in men. Asian J. Androl. 14 428–435. 10.1038/aja.2012.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöhammer C., Brunner F., Wölkart G., Staber P. B., Steyrer E., Gonzalez F. J., et al. (2003). Myocardial dysfunction and male mortality in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha knockout mice overexpressing lipoprotein lipase in muscle. Lab. Invest. 83 259–269. 10.1097/01.LAB.0000053916.61772.CA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogola B. O., Zimmerman M. A., Sure V. N., Gentry K. M., Duong J. L., Clark G. L., et al. (2019). G Protein-coupled estrogen receptor protects from angiotensin ii-induced increases in pulse pressure and oxidative stress. Front. Endocrinol. 10:586. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S. B., Subrayan S., Lim S. Y., Yellon D. M., Davidson S. M., Hausenloy D. J. (2010). Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 121 2012–2022. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.906610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou K. N., Kikuchi R., Ngoh G. A., Coughlan K. A., Dominguez I., Stanley W. C., et al. (2012). Mitofusins 1 and 2 are essential for postnatal metabolic remodeling in heart. Circ. Res. 111 1012–1026. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.-M., Pereira R. I., Erickson C. B., Swibas T. A., Kang C., Van Pelt R. E. (2017). Time since menopause and skeletal muscle estrogen receptors. PGC-1α, and AMPK. Menopause 24 815–823. 10.1097/GME.0000000000000829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra V., Eisner V., Chiong M., Criollo A., Moraga F., Garcia A., et al. (2008). Changes in mitochondrial dynamics during ceramide-induced cardiomyocyte early apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 77 387–397. 10.1093/cvr/cvm029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedernera E., Gómora M. J., Meneses I., De Ita M., Méndez C. (2017). Androgen receptor is expressed in mouse cardiomyocytes at prenatal and early postnatal developmental stages. BMC Physiol. 17:7. 10.1186/s12899-017-0033-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N., Meijer M. (1997). The tom and tim machine. Curr. Biol. 7 R100–R103. 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00048-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton P., Giorgi C., Siviero R., Zecchini E., Rizzuto R. (2008). Calcium and apoptosis: ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer in the control of apoptosis. Oncogene 27 6407–6418. 10.1038/onc.2008.308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquereau J., Caffin F., Novotova M., Prola A., Garnier A., Mateo P., et al. (2012). Down-regulation of OPA1 alters mouse mitochondrial morphology, PTP function, and cardiac adaptation to pressure overload. Cardiovasc. Res. 94 408–417. 10.1093/cvr/cvs117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquereau J., Novotova M., Fortin D., Garnier A., Ventura-Clapier R., Veksler V., et al. (2010). Postnatal development of mouse heart: formation of energetic microdomains. J. Physiol. 588(Pt 13), 2443–2454. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozdniakova S., Guitart-Mampel M., Garrabou G., Di Benedetto G., Ladilov Y., Regitz-Zagrosek V. (2018). 17beta-Estradiol reduces mitochondrial cAMP content and cytochrome oxidase activity in a phosphodiesterase 2-dependent manner. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175 3876–3890. 10.1111/bph.14455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugach E. K., Blenck C. L., Dragavon J. M., Langer S. J., Leinwand L. A. (2016). Estrogen receptor profiling and activity in cardiac myocytes. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 431 62–70. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranki H. J., Budas G. R., Crawford R. M., Davies A. M., Jovanovic A. (2002). 17Beta-estradiol regulates expression of K(ATP) channels in heart-derived H9c2 cells. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 40 367–374. 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01947-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmann M., Dodson M., Boyer-Guittaut M., Darley-Usmar V., Zhang J. (2014). Mitophagy mechanisms and role in human diseases. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 53 127–133. 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosano G. M. C., Leonardo F., Pagnotta P., Pelliccia F., Panina G., Cerquetani E., et al. (1999). Acute anti-ischemic effect of testosterone in men with coronary artery disease. Circulation 99 1666–1670. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.13.1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw J. E., Anderson G. L., Prentice R. L., LaCroix A. Z., Kooperberg C., Stefanick M. L., et al. (2002). Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288 321–333. 10.1001/jama.288.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K., Kurokawa J. (2019). Involvement of sex hormonal regulation of K+ channels in electrophysiological and contractile functions of muscle tissues. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 139 259–265. 10.1016/j.jphs.2019.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samavat H., Kurzer M. S. (2015). Estrogen metabolism and breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 356(2 Pt A), 231–243. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstede J., Lipke C., Beer M., Hofmann S., Pabst T., Kenn W., et al. (2000). Age- and gender-specific differences in left and right ventricular cardiac function and mass determined by cine magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. Radiol. 10 438–442. 10.1007/s003300050072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santulli G., Xie W., Reiken S. R., Marks A. R. (2015). Mitochondrial calcium overload is a key determinant in heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 11389–11394. 10.1073/pnas.1513047112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Serra J., Nadal-Serrano M., Pons D. G., Roca P., Oliver J. (2013). The over-expression of ERbeta modifies estradiol effects on mitochondrial dynamics in breast cancer cell line. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 45 1509–1515. 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbert-Roig M., Bauza-Thorbrugge M., Galmes-Pascual B. M., Capllonch-Amer G., Garcia-Palmer F. J., Llado I., et al. (2016). GPER mediates the effects of 17beta-estradiol in cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 420 116–124. 10.1016/j.mce.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M., Bonekamp N. A., Islinger M. (2012). Fission and proliferation of peroxisomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1822 1343–1357. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M., Fahimi H. D. (2006). Peroxisomes and oxidative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763 1755–1766. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segawa T., Nau M. E., Xu L. L., Chilukuri R. N., Makarem M., Zhang W., et al. (2002). Androgen-induced expression of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response genes in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 21 8749–8758. 10.1038/sj.onc.1205992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidlmayer L. K., Kuhn J., Berbner A., Arias-Loza P.-A., Williams T., Kaspar M., et al. (2016). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial crosstalk influences adenosine triphosphate production via mitochondrial Ca 2+ uptake through the mitochondrial ryanodine receptor in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 112 491–501. 10.1093/cvr/cvw185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirihai O. S., Song M., Dorn G. W., II (2015). How mitochondrial dynamism orchestrates mitophagy. Circ. Res. 116 1835–1849. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siasos G., Tsigkou V., Kosmopoulos M., Theodosiadis D., Simantiris S., Tagkou N. M., et al. (2018). Mitochondria and cardiovascular diseases-from pathophysiology to treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 6:256. 10.21037/atm.2018.06.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M., Mihara K., Chen Y., Scorrano L., Dorn G. W., II (2015). Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts. Cell Metab. 21 273–286. 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer M. J., Colditz G. A., Willett W. C., Manson J. E., Rosner B., Speizer F. E., et al. (1991). Postmenopausal estrogen therapy and cardiovascular disease. Ten-year follow-up from the nurses’ health study. N. Engl. J. Med. 325 756–762. 10.1056/NEJM199109123251102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehlow K., Rotter S., Wassmann S., Adam O., Grohe C., Laufs K., et al. (2003). Modulation of antioxidant enzyme expression and function by estrogen. Circ. Res. 93 170–177. 10.1161/01.RES.0000082334.17947.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian M., Shaha C. (2007). Up-regulation of Bcl-2 through ERK phosphorylation is associated with human macrophage survival in an estrogen microenvironment. J. Immunol. 179 2330–2338. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Zhao M., Yu X. J., Wang H., He X., Liu J. K., et al. (2013). Cardioprotection by acetylcholine: a novel mechanism via mitochondrial biogenesis and function involving the PGC-1alpha pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 228 1238–1248. 10.1002/jcp.24277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas S., Brashear L., Escoto A.-K., Lynch S., Slaughter D., Xavier N., et al. (2019). Sex Differences in Obesity-Induced Inflammation. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang S., Wong S. S. C., Wu S., Kravtsov G. M., Wong T.-M. (2009). Testosterone-augmented contractile responses to α1- and β1-adrenoceptor stimulation are associated with increased activities of RyR, SERCA, and NCX in the heart. Am. J. f Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296 C766–C782. 10.1152/ajpcell.00193.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt R. E., Gavin K. M., Kohrt W. M. (2015). Regulation of body composition and bioenergetics by estrogens. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 44 663–676. 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varanita T., Soriano M. E., Romanello V., Zaglia T., Quintana-Cabrera R., Semenzato M., et al. (2015). The OPA1-dependent mitochondrial cristae remodeling pathway controls atrophic, apoptotic, and ischemic tissue damage. Cell Metab. 21 834–844. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura-Clapier R., Moulin M., Piquereau J., Lemaire C., Mericskay M., Veksler V., et al. (2017). Mitochondria: a central target for sex differences in pathologies. Clin. Sci. 131 803–822. 10.1042/CS20160485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura-Clapier R., Piquereau J., Veksler V., Garnier A. (2019). Estrogens, estrogen receptors effects on cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondria. Front. Endocrinol. 10:557. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicencio J. M., Ibarra C., Estrada M., Chiong M., Soto D., Parra V., et al. (2006). Testosterone induces an intracellular calcium increase by a nongenomic mechanism in cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Endocrinology 147 1386–1395. 10.1210/en.2005-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virani S. S., Alonso A., Benjamin E. J., Bittencourt M. S., Callaway C. W., Carson A. P., et al. (2020). Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation 141 e139–e596. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]