Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Many older people rely on caregivers for support. Caring for older people can pose significant burdens for caregivers yet may also have positive effects. This study aimed to assess the impact on the caregivers and to determine factors associated with caregivers who were burdened.

METHODS:

This was a cross-sectional study of 385 caregivers of older people who attended a community clinic in Malaysia. Convenience sampling was employed during the study period on caregivers who were aged ≥ 21 years and provided ≥ 4 hours of unpaid support per week. Participants were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire, which included the Carers of Older People in Europe (COPE) index and the EASYCare Standard 2010 independence score. The COPE index was used to assess the impact of caregiving. A highly burdened caregiver was defined as one whose scores for all three COPE subscales were positive for burden. Care recipients’ independence was assessed using the independence score of the EASYCare Standard 2010 questionnaire. Multiple logistic regression was used to determine the factors associated with caregiver burden.

RESULTS:

73 (19.0%) caregivers were burdened, of whom two were highly burdened. Caregivers’ median scores on the positive value, negative impact and quality of support scales were 13.0, 9.0 and 12.0, respectively. Care recipients’ median independence score was 18.0. Ethnicity and education levels were found to be associated with caregiver burden.

CONCLUSION:

Most caregivers gained satisfaction and felt supported in caregiving. Ethnicity and education level were associated with a caregiver being burdened.

Keywords: burden, caregivers, EASYCare, quality of life, standard of care

INTRODUCTION

The world is ageing rapidly, particularly in developing countries. It is estimated that by 2050, nearly a quarter of the population in Asia will be aged 60 years and above.(1) In Malaysia, the number of older persons increased from 1.4 million, or 6.3% of the total population, in 2000 to 2.4 million, 8.2% of the total population, in 2012.(2,3) This has had a great impact on healthcare costs and resource utilisation.(4) Many countries are pursuing policies to enable older people to live at home for as long as possible.(5) This approach is likely to increase the pressure on the family and other informal caregivers, who provide up to 80% of the support needed by older people.(5)

Caregivers are essential sources of support to older people, taking responsibility for most of the needs of care recipients. A caregiving relationship can be satisfying as well as burdensome to caregivers.(6) Although many caregivers find that aspects of the caregiving role are satisfying, it can also lead to a decline in their physical and mental health.(6) Caregiving can affect their employment, educational prospects, finances and social life.(7) Therefore, it is vital to consider both the positive and negative aspects when one is assessing the impact of caregiving.(6,8-10)

Malaysia is a multiracial country with diverse cultures, with the Malays, Chinese and Indians as the main ethnic groups. There is a lack of data on the impact of caregiving on caregivers and its associated factors. Studies previously conducted in Malaysia on caregiving had a small sample size, and conflicting factors were associated with caregiver burden.(11-14) One local study that recruited 70 participants found that ethnicity was an associated factor,(14) while another local study with 96 participants found that marital status and family income were associated with caregiver burden.(12) Therefore, this study aimed to determine the impact of caregiving among caregivers of older people in the community and the factors associated with caregiver burden. More insight into the impact of caregiving would enable better planning of future interventions.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a public urban primary care clinic in the state of Selangor, Malaysia, from October to December 2013. Convenience sampling was used. All attendees of the primary care clinic during the study period were approached to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were caregivers aged ≥ 21 years who provided ≥ 4 hours of unpaid support per week (including organising support) to an older person aged ≥ 65 years living in the community. Exclusion criteria were those who were unable to understand English or Malay (i.e. the national language) and those who only provided financial support or companionship.

Caregivers who consented to participate were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire with four sections, which consisted of: (a) the caregiver’s sociodemographic data; (b) the Carers of Older People in Europe (COPE) index; (c) the care recipient’s sociodemographic data and medical conditions; and (d) the 18-item independence score from the EASYCare Standard 2010 questionnaire.(15,16) If the care recipient was present, a face-to-face interview was conducted to obtain data on sociodemographic information, medical conditions and independence score. If the care recipient was not present, a contact number was taken and the interview was conducted via a telephone call.

Two instruments were used: the COPE index and the independence score from the EASYCare Standard 2010 questionnaire.(15,16) The COPE index is a screening instrument used to assess the needs of caregivers of older people.(16,17) It has 15 items that can be summed up to indicate how well the caregiver is coping with the caregiving relationship. The COPE index has three subscales: the positive value, negative impact and quality of support scales. The positive value scale relates to personal gain or satisfaction in caregiving(16,17) and ranges from 4 to 16, with a higher score denoting greater satisfaction in caregiving. The negative impact scale relates to a personal feeling of being stressed in caregiving and ranges from 7 to 28, with a higher score denoting more negative impact from caregiving. The quality of support scale relates to caregivers’ perceived feeling of being supported in their caregiving role and ranges from 4 to 16, with a higher score denoting feeling supported in the caregiving role. The operational definition of a caregiver who was burdened was one who scored > 15 for negative impact, < 10 for positive value, or < 6 for quality of support.(16,17) A caregiver who was highly burdened was one whose scores for all three scales were positive for burden.

The independence score was used to assess the level of independence of the older people in performing activities of daily living.(15) It was developed by incorporating the Barthel index with the Duke OARS (Older Americans Resources and Services) IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) Scale,(18) and is a self-assessment tool, unlike most other instruments that require assessment by the healthcare provider.(19) The EASYCare Standard 2010 questionnaire has been validated in community-dwelling older people in Malaysia(20) and India.(19) It contains 18 items that assess the care recipient’s needs for care and support,(21) with a total score ranging from 0 to 100. A high score is associated with a high need for support. The COPE index and the independence score from the EASYCare Standard 2010 questionnaire have been validated in six European countries.(10,17,22) The questionnaire was translated into the Malay language using a forward and backward translation procedure. A pilot study was then conducted to examine the feasibility of the study and to pretest the questionnaire in the Malay language to assess its face validity. The questionnaire was found to be easily understood and no amendments were made.

A test-retest reliability test was conducted on the COPE index among 30 respondents. It showed moderate to almost perfect agreement (Cohen’s Kappa range 0.545–0.892) for all items, except for one (‘Does caregiving cause you financial difficulties?’), which had fair agreement (Kappa 0.339). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.829 for the negative impact scale, 0.653 for the positive value scale and 0.743 for the quality of support scale.

Data was analysed using SPSS Statistics version 19.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-square test was used to check for possible associations between categorical variables. Variables with p < 0.25 were then included in the multivariable analysis to adjust for confounders. Simple logistic regression was used for bivariate analysis before multiple logistic regression was performed to determine the factors associated with caregiver burden. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (reference no. 938.15) and the National Institute of Health, Ministry of Health, Malaysia (reference no. NMRR-13-767-16773).

RESULTS

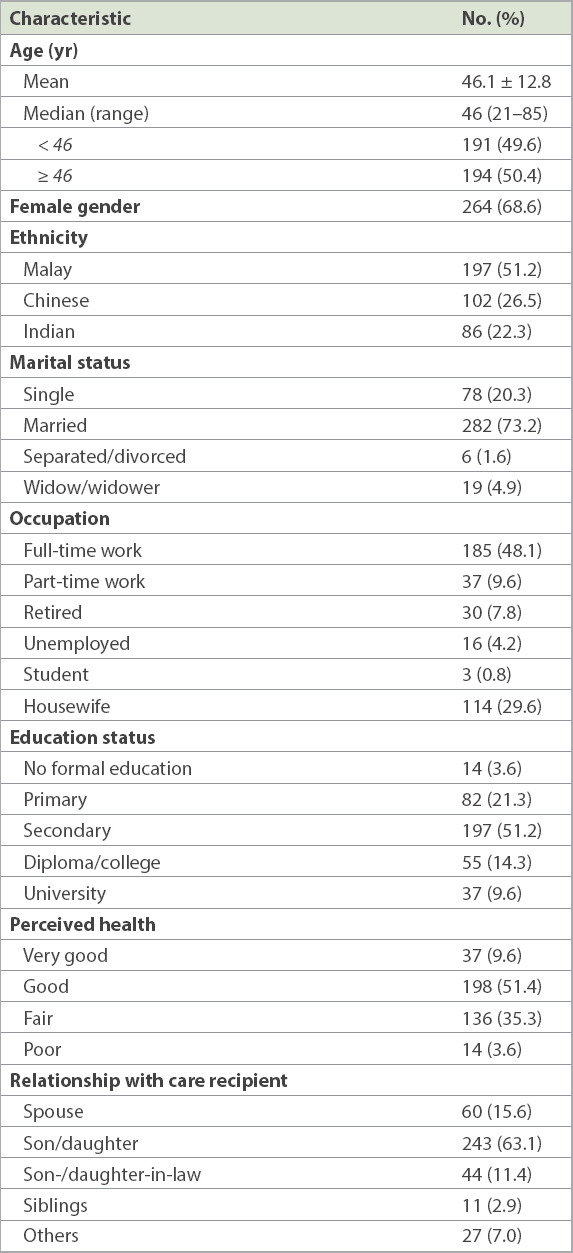

A total of 435 eligible patients were approached, of whom 385 agreed to participate, giving a response rate of 88.5%. Table I summarises the sociodemographic data of the caregivers. Their mean age was 46.1 ± 12.8 years, and nearly 90% of them were aged < 65 years. About two-thirds were female and more than half (57.7%) were working full- or part-time. Most perceived themselves to have fair to very good health. About 90% of the caregivers were members of the family. Most stayed in the same household as the care recipient and 93.2% did not employ a domestic helper. 81.0% of caregivers took care of one older person and 19.0% took care of two.

Table I.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers (n = 385).

There were 383 care recipients. Two of them each had two caregivers, all of whom participated in this study. The mean age of the care recipients was 73.5 ± 7.4 (range 65–106) years. 269 (70.2%) of the care recipients were female and 59 (15.4%) stayed near a clinic at a mean distance of 4.2 ± 1.9 km from home. Nearly all of the care recipients (98.2%, n = 376) did not employ a domestic helper. 369 (96.3%) care recipients had chronic diseases: 298 (77.8%) had hypertension and 207 (54.0%) had diabetes mellitus. The mean and median independence score was 25.8 ± 23.0 (range 0–98) and 18.0, respectively.

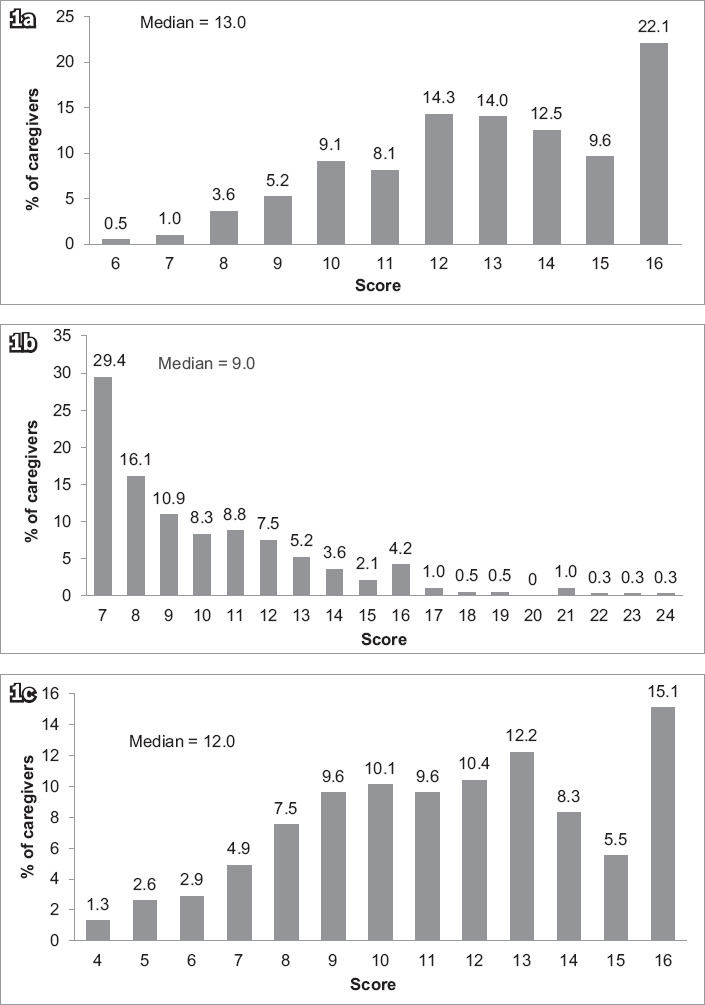

Fig. 1 shows the proportions of caregivers’ COPE index scores (positive value, negative impact of caregiving and quality of support). Among those who were burdened, the subscales that contributed the most were the positive value score (54.8%), followed by the negative impact (42.5%) and quality of support (20.5%) scores. 73 (19.0%) caregivers were found to be burdened and two of them were highly burdened. Both caregivers who were highly burdened were Chinese and single, and were children of the care recipients. The first, a woman, was looking after her mother who had dementia and an independence score of 42. The other was a man who looked after a parent with chronic diseases and had an independence score of 34.

Fig. 1.

Bar charts show the proportions of the caregivers’ scores on the COPE index subscales of (a) positive value; (b) negative impact; and (c) quality of support. COPE: Carers of Older People in Europe

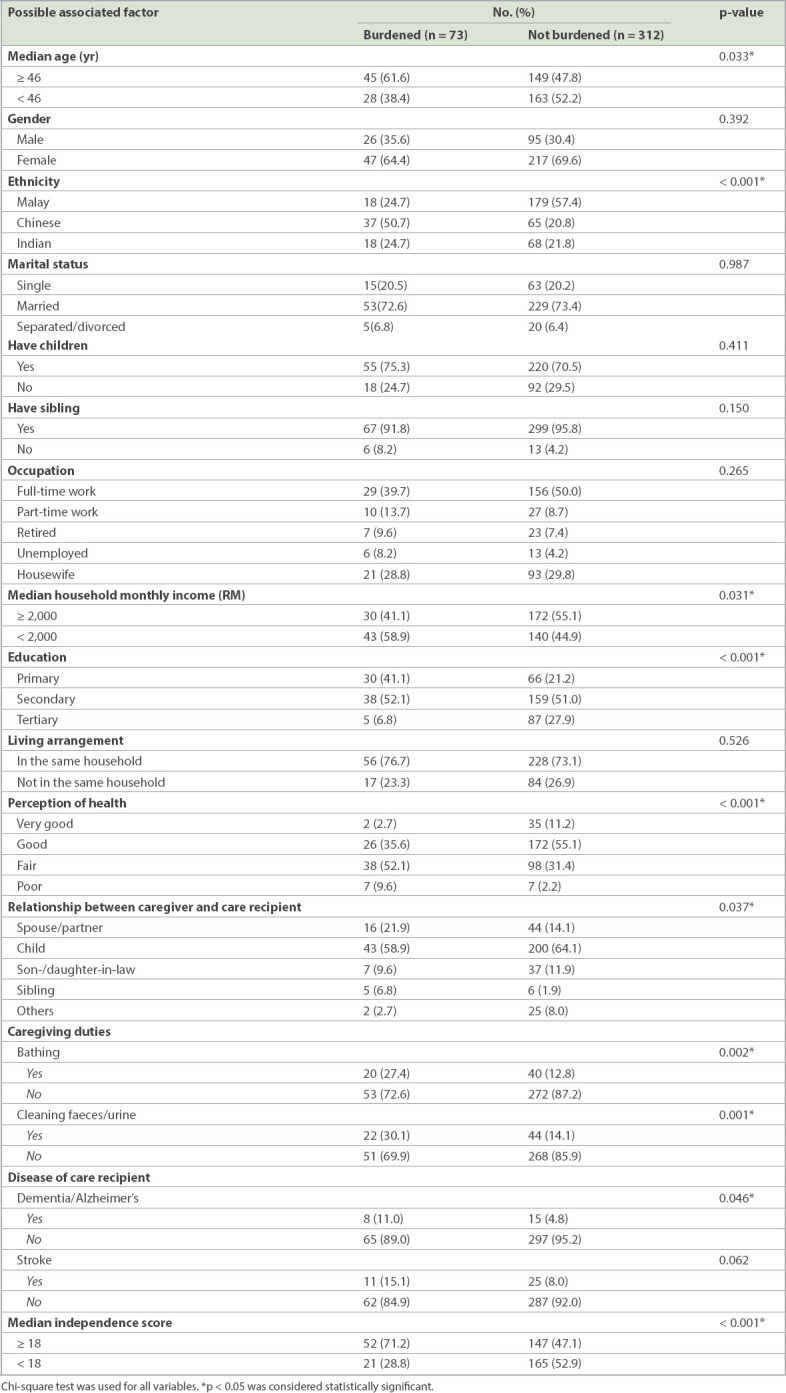

Possible factors associated with caregivers who were burdened were analysed using chi-square test (Table II). Marital status, occupation, education status, household income and perception of health were regrouped because of small numbers in certain groups prior to analysis. Median age, ethnicity, education status, median household income, perception of health, caregiving duties (bathing and cleaning faeces/urine), relationship between caregiver and care recipients, diseases (dementia), and independence scores of care recipients were factors that were significantly associated with caregivers who were burdened.

Table II.

Association between possible factors and caregivers who were burdened.

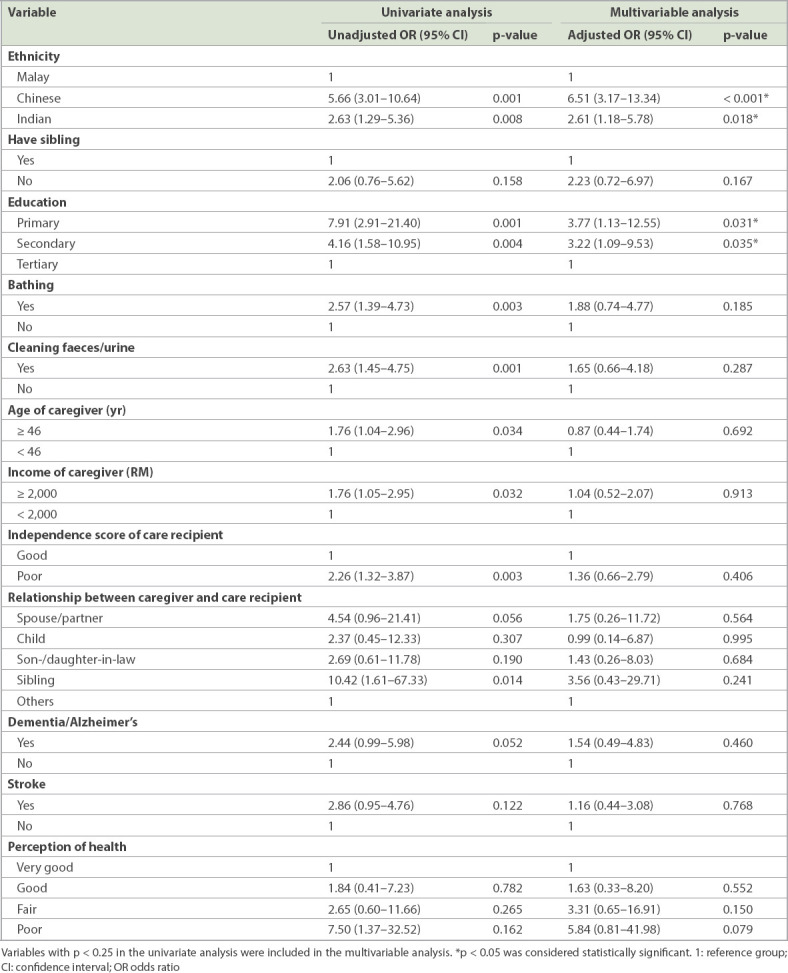

Multivariable analysis was used to analyse the factors associated with caregivers who were burdened (Table III). All variables with p < 0.25 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. After adjusting for age, ethnicity, education status, the presence of siblings, perception of health, caring duties (bathing and cleaning faeces/urine), household income of caregivers, relationship between caregiver and care recipients, diseases of care recipients (dementia and stroke), and independence score of care recipients, the factors that were independently associated with caregivers who were burdened were ethnicity and education. The Chinese and Indian caregivers felt more burdened than the Malay caregivers, with odds ratios of 6.51 and 2.61, respectively. Caregivers with primary and secondary education had 3.77 and 3.22 times the odds, respectively, of being burdened compared with those who had tertiary education.

Table III.

Univariate and multivariable analysis (n = 385).

DISCUSSION

Our research showed that caregiver burden is common, with one out of every five caregivers in this study population feeling burdened, even though most of the corresponding care recipients were generally independent and living in the community. Nevertheless, most caregivers were found to have gained satisfaction and felt supported in their role of caring for older people. Few caregivers felt the negative impact of caregiving. Caregiver burden was found to be associated with ethnicity and education level.

Ethnicity was found to be an independent factor associated with caregivers who were burdened. More Chinese and Indian caregivers were found to be burdened in the caregiving role compared with Malay caregivers; the two caregivers who were highly burdened were both Chinese. This finding is similar to that of a study done among caregivers of patients with dementia in Malaysia, which showed that Chinese caregivers had a higher level of burden compared to Indian and Malay caregivers.(14) A recent meta-analysis examining ethnicity and cultural influences in caregiving found that caregiving experiences and outcome varied across racial and ethnic groups.(23) It was suggested that this was due to cultural differences in perceptions of illness and the meaning of caregiving. If caregiving is viewed as self-sacrificing in one’s culture, caring for older people may be regarded as a source of pride and status. One possible reason for the finding that Malay caregivers reported a lower burden is that they were unable to express that they felt burdened.(24) According to Malay culture and Islam, difficulties are seen to be the will of God, hence a Muslim should be accepting of his fate.(14,24) Although social support is a possible factor affecting caregiver burden, we did not find this to be so in our population, as household income, having siblings and having children were not significantly associated with caregiver burden.

Most caregivers in this study were found to be immediate family members of the care recipients. All cultures in the Malaysian population still closely comply with filial obligations and the societal norm of assigning the responsibility of caring for impaired older people to their families.(25) Notably, cultural differences may affect the relationship between filial obligation and burden in the caregiving process.(23) A study in Taiwan found that filial obligation was a strong predictor of burden among caregivers.(26) This suggested that filial obligation may be the primary motive for caregiving, as a result of the value placed on filial piety in Chinese culture. However, in this study, the relationship between caregivers and care recipients was not significantly associated with caregivers being burdened.

The other significant independent factor in this study was the education level of caregivers. Caregivers with a lower education level were more burdened compared with those of a higher education level. This finding was similar to that of a study done among spouse caregivers, which found that less educated caregivers reported more negative effects of caregiving.(27) In contrast, people with better education were more likely to see caregiving as meaningful and satisfying.(27,28) This can probably be attributed to better coping skills among more highly educated caregivers.

In bivariate analysis, the independence level of the care recipients was found to be significantly associated with caregivers who were burdened, suggesting that caregivers who were burdened were looking after care recipients who were more dependent. This finding was consistent with other studies showing that the more dependent the care recipient, the higher the likelihood of there being a higher burden on caregivers.(29,30) However, the association was not significant after adjusting for confounders. The literature has shown that a caregiver’s burden is mainly affected by care recipients’ characteristics and caregivers’ characteristics, with the latter being the stronger predictor of caregiver outcomes.(31) However, the fact that our caregivers were shown to gain satisfaction (i.e. positive value) and had less negative impact from caregiving could also have influenced their perception of burden.

There is a paucity of research on caregivers of older people. In addition, most of the previous studies were done on caregivers of care recipients who had specific diseases such as dementia or stroke. As the caregivers recruited for this study were clinic attendees looking after older persons in the community who ranged from independent to very dependent, they were more reflective of the typical caregiver in the community. Findings from this research contribute to our understanding of the positive value and negative impact of caregiving as well as the quality of support perceived by caregivers of older people.

The present study was limited by the varying interview methods used to assess the dependency level of the care recipients, which may have created reporting bias. Most care recipients were able to answer the questions that assessed their dependency level. However, some care recipients were very ill; could not communicate due to slurred speech as a result of a stroke, hearing impairment or cognitive impairment; or had a language barrier and refused to answer telephone calls. In these circumstances, the assessment was done by asking their caregivers. The study was also limited by convenience sampling, but we minimised potential bias by including all caregivers who attended the clinic during the recruitment period. Nevertheless, our findings have provided insight into the burden of caregivers, which is an important aspect of clinical care.

Ethnicity and education were found to be independent factors associated with caregivers who were burdened. Similarly, a previous study on patients with dementia in Malaysia reported that the Chinese were likely to have greater caregiver burden than the Indians and Malays.(14) Other studies also observed that caregivers with better education felt less burdened than those with less education and were more likely to see caregiving as meaningful and satisfying.(27,28) Future research should explore the different perceptions of caregiving among the ethnic groups and confirm the findings on education levels so that interventions can be made to support and improve caregiver health. In addition, qualitative studies on caregivers’ experiences would help to improve our understanding of their challenges and to find possible ways to change their sense of burden.

Caregivers in this study gained satisfaction from caregiving, had less negative impact from it and perceived themselves as receiving good quality of support. Previous studies have mainly focused on negative aspects of caregiving, but the positive value of caregiving and quality of support perceived by caregivers are also important to determine the overall impact of caregiving. A better understanding is needed of the factors related to positive experiences among caregivers and their care needs in future research that may potentially inform policies for older person care.

In this study, it appeared that the more dependent the older people, the more likely the caregivers were to be burdened, although there was no significant association in multivariable analysis. Nevertheless, it is still important for healthcare providers, especially primary care physicians, to identify caregivers who care for dependent older people in the community. Community-level screening for distress among caregivers can be done so that timely interventions can be carried out.

In conclusion, the majority of the caregivers in our study gained satisfaction and felt supported in their role. Few perceived that caregiving had a negative impact. The study also found that ethnicity and education level were factors associated with caregiver burden. Chinese caregivers had 6.51 times the odds and Indian caregivers 2.61 times the odds to be burdened than the Malay caregivers. Caregivers with lower education were more burdened compared with those with higher education. Future research should explore the different cultural perceptions among ethnic groups on caregiving so that culture-sensitive interventions can be made.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the Director General of Health, Ministry of Health, Malaysia, for approving the publication of this paper. We would also like to thank all caregivers and care recipients for participating in this research. This work was supported by the Postgraduate Research Fund, University of Malaya, Malaysia (P0029/2013A).

REFERENCES

- 1.UNFPA, HelpAge. International Ageing in the Twenty-First Century:A Celebration and a Challenge. New York: UNFPA and HelpAge International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mat R, Taha HM. Presented at the 21st Population Census Conference, 19-21 November. Kyoto, Japan: 2003. [Accessed December 5 2013]. Socio-economic characteristics of the elderly in Malaysia. Available at: https://tongkk.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/malaysia.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zawawi R. Active ageing in Malaysia. Presented at the Second Meeting of the Committee on International Cooperation on Active Ageing, 19 July. 2013. [Accessed January 4 2014]. Tokyo, Japan. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r98520000036yla-att/2r98520000036yqa_1.pdf .

- 4.Poi PJ, Forsyth DR, Chan DK. Services for older people in Malaysia:issues and challenges. Age Ageing. 2004;33:444–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker A, Guillemard AM, Alber J. Older people in Europe:social and economic policies. The 1993 Report of the European Observatory. Brussels:Commission of the European Committees. 1993. Available at: http://aei.pitt.edu/58285/1/A7962.pdf. Accessed December 20 2013.

- 6.Chappell NL, Dujela C. Caregiving:predicting at-risk status. Can J Aging. 2008;27:169–79. doi: 10.3138/cja.27.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron ID, Aggar C, Robinson AL, Kurrle SE. Assessing and helping carers of older people. BMJ. 2011;343:d5202. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekwall AK, Hallberg IR. The association between caregiving satisfaction, difficulties and coping among older family caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:832–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis A, Worth A, Porter M. The experience of caring for someone over 75 years of age:results from a Scottish General Practice population. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1450–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balducci C, Mnich E, McKee KJ, et al. Negative impact and positive value in caregiving:validation of the COPE index in a six-country sample of carers. Gerontologist. 2008;48:276–86. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu Bakar SH, Weatherley R, Omar N, Abdullah F, Mohamad Aun NS. Projecting social support needs of informal caregivers in Malaysia. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22:144–54. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fatimang L, Rahmah MA. [Care of stroke patients:are they a burden?] Malaysian J Community Health. 2011;17:32–41. Malay. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zainuddin J, Arokiasamy JT, Poi PJ. Caregiving burden is associated with short rather than long duration of care for older persons. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2003;15:88–93. doi: 10.1177/101053950301500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choo WY, Low WY, Karina R, et al. Social support and burden among caregivers of patients with dementia in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2003;15:23–9. doi: 10.1177/101053950301500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The EASY-Care Foundation. Instruments. [Accessed July 30 2013]. Available at: http://www.easycare.org.uk/instruments.

- 16.Nolan M, Philp I. COPE:towards a comprehensive assessment of caregiver need. Br J Nurs. 1999;8:1364–72. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1999.8.20.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKee KJ, Philp I, Lamura G, et al. COPE Partnership. The COPE index--a first stage assessment of negative impact, positive value and quality of support of caregiving in informal carers of older people. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:39–52. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000006956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. J Gerontol. 1981;36:428–34. doi: 10.1093/geronj/36.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jotheeswaran AT, Dias A, Philp I, Patel V, Prince M. Calibrating EAST-Care independence scale to improve accuracy. Age Ageing. 2016;45:890–3. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valarmathi M, Khoo EM, Sajaratulnisah O, et al. Validity and reliability of the Easy-Care Standard 2010 questionnaire among elderly people in a Malaysian community health clinic. Presented at EASY-Care International Research and Publication Meeting, Istanbul. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobis S, Jaracz K, Talarska D, et al. Validity of the EASYCare Standard 2010 assessment instrument for self–assessment of health, independence, and well-being of older people living at home in Poland. Eur J Ageing. 2017;15:101–8. doi: 10.1007/s10433-017-0422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philip KE, Alizad V, Oates A, et al. Development of EASY-Care, for brief standardized assessment of the health and care needs of older people;with latest information about cross-national acceptability. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research:a 20-year review (1980-2000) Gerontologist. 2002;42:237–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salleh MR. The burden of care of schizophrenia in Malay families. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:180–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb08089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arokiasamy JT. Malaysia's ageing issues. Med J Malaysia. 1997;52:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou KR, LaMontagne LL, Hepworth JT. Burden experienced by caregivers of relatives with dementia in Taiwan. Nurs Res. 1999;48:206–14. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hughes SL, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weaver FM, Kubal JD, Henderson W. Relationship between caregiver burden and health-related quality of life. Gerontologist. 1999;39:534–45. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beach SR, Schulz R, Yee JL, Jackson S. Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse:longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:259–71. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin IF, Fee HR, Wu HS. Negative and positive caregiving experiences:a closer look at the intersection of gender and relationships. Fam Relat. 2012;61:343–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00692.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawton MP, Moss M, Kleban MH, Glicksman A, Rovine M. A two-factor model of caregiving appraisal and psychological well-being. J Gerontol. 1991;46:181–9. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.4.p181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunkin JJ, Anderson-Hanley C. Dementia caregiver burden:a review of the literature and guidelines for assessment and intervention. Neurology. 1998;51(1 Suppl 1):S53–S60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.1_suppl_1.s53. discussion S65-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]