Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Elderly persons who live alone are more likely to be socially isolated and at increased risk of adverse health outcomes, unnecessary hospital re-admissions and premature mortality. We aimed to understand the health-seeking behaviour of elderly persons living alone in public rental housing in Singapore.

METHODS:

In-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured question guide. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling approach. Interviews were conducted until theme saturation was reached. Qualitative data collected was analysed using manual thematic coding methods.

RESULTS:

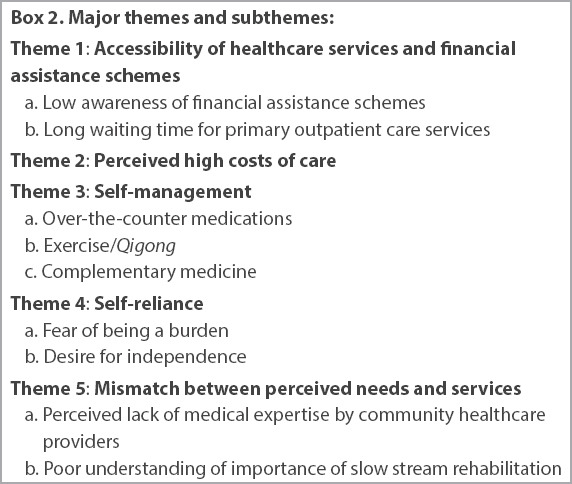

Data analysis revealed five major themes: accessibility of healthcare services and financial assistance schemes; perceived high cost of care; self-management; self-reliance; and mismatch between perceived needs and services.

CONCLUSION:

Elderly persons living in one-room rental flats are a resilient and resourceful group that values self-reliance and independence. Most of the elderly who live alone develop self-coping mechanisms to meet their healthcare needs rather than seek formal medical consultation. The insightful findings from this study should be taken into consideration when models of healthcare delivery are being reviewed and designed so as to support the disadvantaged elderly living alone.

Keywords: elderly, health-seeking behaviour, loneliness, social isolation

INTRODUCTION

Similar to many developed countries worldwide, Singapore’s population is ageing rapidly. According to the census from the year 2000, elderly persons aged above 65 years constituted 7.2% of Singapore’s population, and this was projected to rise to more than 19% by 2030.(1,2) As early as 1984, the Singapore government had anticipated the implications of an ageing population. The Committee on the Problems of the Aged (1982–1984), chaired by the then Minister of Health, was formed to design and implement solutions for the ageing population in Singapore in order to tackle the increasing burden on the healthcare system.(3) As part of this move, a wide array of government-subsidised community healthcare services and financial assistance schemes have been set up to cater to the biopsychosocial needs of the elderly.(3)

Within the rapidly ageing population is a subset of elderly people who live alone in public rental flats with poor housing conditions and who have limited social and financial resources. They are at increased risk of ill health with higher rates of hospital re-admissions, as well as mortality due to poor health literacy, social isolation and financial constraints.(4-6) This observation – that patients who have lower socioeconomic status and are socially isolated are at greater risk of experiencing poor health outcomes – has led to socioeconomic status being considered for inclusion in newly developed hospital re-admission measurement models to calculate risks of re-admissions and prolonged hospital stay.(7,8)

Based on the 2014 population census, about 5.3% of resident households in Singapore reside in public rental housing, and the percentage of elderly solo dwellers has been steadily increasing.(1,2) To be eligible for public rental housing, total household gross income must not exceed SGD 1,500 per month. Therefore, public rental housing is an appropriate area-level measure of socioeconomic status.

A study conducted by Low et al in Singapore found that elderly persons living in public one-room rental housing have higher odds of being re-admitted to an acute hospital within 15 days (19%) and 30 days (27%). These results were statistically significant (p < 0.001) even after adjusting for demographics and clinical conditions that are known to affect re-admission risk and utilisation of hospital services.(4,6) In a separate study, Ng et al used data from eight years of mortality follow-up of 2,553 participants in the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies and found that living alone was associated with increased mortality, with a hazard ratio of 1.66 (95% confidence interval 1.05–2.63), independently of marital status, health and other variables.(9)

While living alone and low socioeconomic status are proxy measures of poor health outcomes and mortality, understanding the health-seeking behaviour of these at-risk elderly people will provide useful insights into the interactions between socioeconomic status and health outcomes, so that the current gaps in healthcare policymaking and delivery can be filled. This formed the basis for the present research.

METHODS

The approval of the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board was obtained before the study was conducted. The investigators were all practising family physicians caring for the elderly in hospital and home care settings. Participants were recruited from the elderly population living in the Chin Swee residential estate. This residential estate is located within close proximity to Singapore General Hospital (SGH) and consists of two blocks of public one-room rental flats.

Individuals were eligible for inclusion if they were (a) aged 65 years and older at the time of the interview; (b) receiving a form of public financial assistance; (c) living alone in a one-room rental flat; and (d) diagnosed with two or more chronic diseases under the Ministry of Health’s Chronic Disease Management Programme.(10) Residents were approached door-to-door and selected based on purposive sampling. In addition, patients hospitalised at SGH who met the inclusion criteria were approached to participate in the study after they were discharged from hospital.

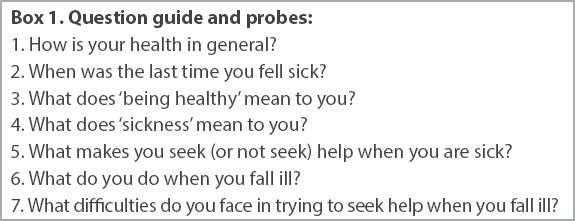

Two interviewers fluent in both written and spoken English and Mandarin conducted the in-depth interviews. The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured question guide in the privacy of the participants’ own homes. The objectives of the study were clearly explained to the participants prior to the start of each interview. Participants were encouraged to speak freely in the language that they were comfortable in (either English or Mandarin) and to highlight issues that were important to them. The questions asked are listed in Box 1. Probes were used as needed to elicit in-depth discussion.

Box 1.

Question guide and probes:

The initial question guide in English was created by two researchers. Two independent translators who were fluent in both written and spoken English and Mandarin conducted forward translation of the question guide from English to Mandarin and checked it iteratively. Reconciliation of any differences between the two forward translations was discussed with the principal investigator. The reconciled translation was then back-translated into the source language and compared with the original question guide to ensure the conceptual equivalence of the translation.

Questions about key concepts were designed to be open-ended and non-leading, based on a comprehensive literature review of the researchers’ previous studies on the impact of living alone and social isolation on health, hospital re-admission risk and mortality.(4,6,8) To formulate the questions, the researchers also drew on their combined experience of commonly encountered issues in elderly people living alone, after a joint discussion among the researchers. The questions were further modified with pilot testing and became more focused with subsequent analyses as common themes emerged through the analytic and reflective processes.

Each in-depth interview was audio-recorded and lasted 40–60 minutes. The interviewers kept a reflexivity diary that included field notes from each interview to ensure rigour. All interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred spoken language (either English or Mandarin). Of the 11 interviews, two were conducted in English and the remaining nine in Mandarin. The Mandarin audio recordings were back-translated into English and then transcribed into written texts. Similarities and differences were compared for accuracy in English.

Data analysis was commenced as soon as the first interview was completed. Two independent coders read each transcript thoroughly and repeatedly after each interview to analyse for meaningful and significant quotes. Constant comparison was used throughout data analysis to compare and contrast emerging data obtained from the initial analysis with data obtained from subsequent interviews. The question guide was subsequently modified in order to further expand on the themes in the setting. The relevant data was categorised to form themes and subthemes. Regular joint discussions were held between the two coders to ensure consensus. If there was disagreement between them, a third independent coder was engaged to analyse the transcripts.

RESULTS

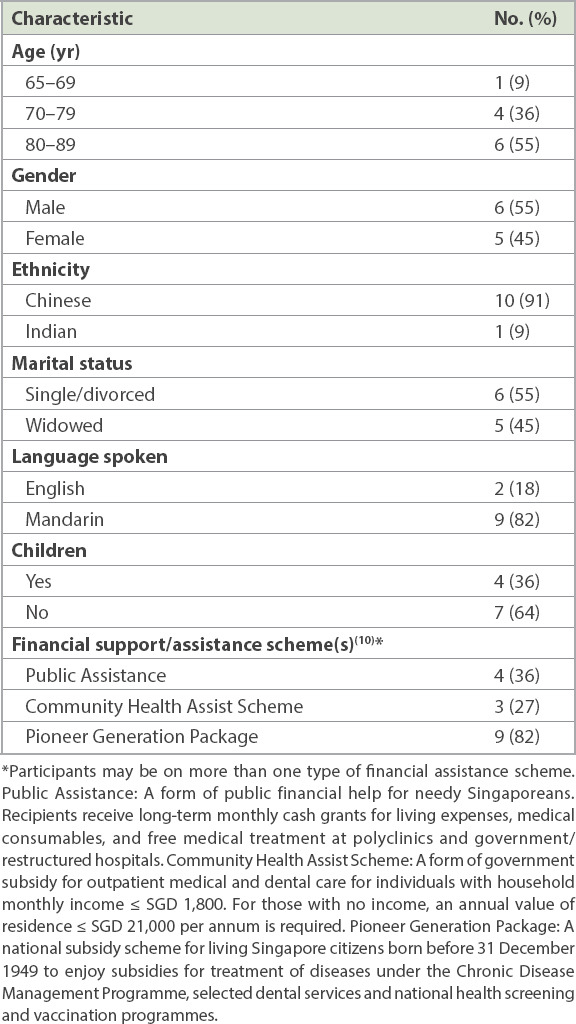

Thematic saturation was reached at 11 interviews. A total of 11 participants (six male, five female) aged 66–88 years participated in the in-depth interviews. Their demographic information is shown in Table I. Five major themes emerged from our analysis (Box 2).

Table I.

Demographic information of participants (n = 11).

Box 2.

Major themes and subthemes:

Theme 1 was the accessibility of healthcare services and financial assistance schemes. In general, there was low awareness of financial assistance schemes. In Singapore, public healthcare is financed by a combination of government subsidies, MediSave (an individual’s medical savings built from part of a working individual’s income), MediShield (a government health insurance scheme for catastrophic illness), ElderShield (a government insurance scheme for elderly persons with severe disabilities) and out-of-pocket payments.(11,12) Many types of financial assistance schemes are available and the coverage for each differs. Some are for outpatient clinic use, while others cover inpatient hospitalisation. Some can be used at private general practitioner (GP) clinics, while others can only be used at government polyclinics. Eligibility is based on means testing and is governed by strict rules.(12) Means testing is a method used to calculate the amount of subsidies that one would receive from the government when using healthcare services. This process requires an initial referral, by the attending doctor during a patient’s hospital stay, to a medical social worker. Family members under the same residential address submit their income documents; the entire household’s income is then calculated to determine the amount of subsidy that each elderly person is eligible to use in intermediate- and long-term care facilities such as nursing homes, community hospitals and community day rehabilitation centres.(12)

Several participants expressed that they were not aware of the existence of subsidy schemes or what benefits they were entitled to. Most of them received subsidy cards only because they were in the national auto-inclusion schemes. They were not aware that one could go to Social Service Offices to apply for financial assistance. Others became aware of their eligibility for financial assistance only upon admission to the hospital and after being referred to a hospital medical social worker.

“I have the red card with a tree (Pioneer Generation or PG card) and the blue card (Community Health Assist Scheme or CHAS card). I didn’t apply for it. They just sent it to me in my mailbox. But I don’t really know how to use it.” (Kwan, 87 years, Chinese, female)

“I didn’t have to apply for these cards. They just came on their own. I don’t think you need to apply for them, do you?” (Chua, 66 years, Chinese, female)

The second subtheme was the long waiting time for primary outpatient care services. Convenience and proximity to residence seemed to be the most important factors that determine where the elderly person goes to seek medical consultation. This is often the government polyclinic in the vicinity. However, the most serious impediment to visiting the polyclinic is the long waiting time, especially for elderly persons with multiple comorbidities and poor functional status, for whom long waiting times often result in physical and psychological stress.

“The waiting time is so long. At most, it should only be 1.5–2 hours of waiting time per patient. But I waited longer than that to see the doctor! Even patients with heart conditions like me were made to wait! Can you imagine how dangerous it is?…I waited so long until I was frustrated and hungry. Yet I was worried if I left for a while to get food, my turn would be over!” (Wong, 75 years, Chinese, male)

“I started queuing at 9 am. I waited for two hours before I saw the doctor. The doctor only saw me for five minutes and then I had to wait another two hours to collect my medications. Some other patients were collecting huge bags of medications. It was very slow and I was just sitting there waiting like a fool.” (Cheong, 78 years, Chinese, male)

Theme 2 was the perceived high costs of care. The majority of the elderly people we interviewed were satisfied with the standard and costs of care at government polyclinics. For participants who did not visit any of the private GP clinics located within the same block of flats, concerns over the cost of care were the main issue. The elderly would travel to a nearby polyclinic where the costs were lower despite the longer travelling distance and waiting time.

“The medicines at the polyclinic are so much cheaper! I get senior citizens subsidies there. I can use the PG card and it’s a lot cheaper than seeing the private GP.” (Cheng, 87 years, Chinese, female)

“Private clinics are expensive. How can I afford? Look at their overheads! Their aircon, their nice office, and the salaries they need to pay to their employees. So they can’t charge you too cheap. It will be expensive, definitely. Otherwise they cannot survive.” (Yeo, 74 years, Chinese, male)

“I don’t have to pay at the polyclinic with this card (Public Assistance [PA] card). Seeing doctor, blood tests, even medications – everything is free for me!” (Tan, 72 years, Chinese, male)

Of the 11 participants, one was still working, in a low-paying job. The rest were either receiving monthly payouts through the PA scheme or living on their own savings.(13) Sources of financial support included family inheritance, personal savings, Central Provident Fund (CPF) savings, allowances from family/friends, and donations from cultural/religious organisations. Although all of the participants were receiving subsidies for healthcare expenses, many still expressed concerns about the high costs of care. One participant shared her experience on the cost of visiting a hospital’s emergency department. Unfortunately for her, the financial assistance scheme she was on entitled her only to subsidised outpatient clinic visits but not emergency department visits.

“I get subsidies for clinic consultations and polyclinics. Just that hospitalisation is worrying and I have to use my daughter’s MediSave account for hospitalisation. Like that day, I needed to pay $100+ in cash for the A&E (Accident and Emergency) visit. I still owe them $60 in cash!” (Chua, 66 years, Chinese, female)

Theme 3 was self-management. Most of the elderly people we interviewed tended to put off seeing a doctor until their condition was perceived to be more serious. Instead, they developed various self-management strategies, including over-the-counter medicine and complementary medicine, as the first-line measures for managing their medical conditions. Given a choice, they would rather take personal responsibility over their own health than rely on external help. This is in keeping with the findings of a local study by Wee et al, who found that individuals of lower socioeconomic status living in public rental housing do not seek medical consultation with Western-trained physicians as a first-line option.(14) This was true in our study population despite the fact that every participant was a user of the public healthcare system and had follow-up visits that were subsidised or paid in full by the government.

Over-the-counter medications, the first subtheme, were perceived by our participants to be safe for use and are often the first-line treatment of choice for common ailments such as arthritic pains, coughs and colds.

“When it is a small illness, I just ignore it and sleep it off. I have some medications at home. Cough syrup, ‘Po Chai’ pills, Panadol and some plasters. I use it for fever, headaches, body aches and knee pain. Just the common medications for the usual problems.” (Cheong, 78 years, Chinese, male)

“For simple coughs and colds, I just take Panadol. There is no need to see a doctor for these things.” (D, 88 years, Indian, female)

The second subtheme was exercise and Qigong. Qigong appeared to be a popular exercise among the elderly living alone. Many participants felt that it was easy to practise and gentle on the joints, and could prevent illness and maintain fitness.

“Every morning, I go to People’s Park Hill to do Qigong . There is a group of old folks there every morning atop the hill. It is easy to follow and it helps me to keep fit. I really enjoy it.” (Chua, 87 years, Chinese, female)

“Ever since I started practicing Qigong , I seldom fall sick any more. Last time when I did not know about Qigong , I used to get colds, coughs and sore throat easily. Not any more now!” (Leong, 81 years, Chinese, male)

Regarding complementary medicine, the third subtheme, there was a mixed response regarding the use of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and its perceived efficacy. This was unexpected, as there is a renowned TCM clinic that provides free clinic consultations and medicine located within walking distance of the residential estate. Some of the participants felt that TCM was difficult to prepare and had low efficacy. Others perceived it to be as effective as Western medicine and would continue to use it.

“I need to cook the herbs myself; it is very troublesome. When you are sick, it is very troublesome to have to cook the medications yourself.” (Gng, 80 years, Chinese, male)

“I have been seeing the TCM doctor for the last 20 years! At first, the medicine was effective, but now there is no more effect from the medicine. I have taken it for so long now that the medicine has lost its effectiveness. So, I do not go anymore.” (Yeo, 74 years, Chinese, male)

“TCM is good! There is no need to pay and you get medications, too. Every day, there are more than 300 patients visiting the ‘sinsehs’. I tried it and it really works; otherwise I would not be going back there again and again. Why do you think there are so many people every day?” (Wong, 75 years, Chinese, male)

Theme 4 was self-reliance. Some of the elderly did not seek or accept help because they expressed fear of being a burden to their loved ones, family and society. They were afraid of receiving disturbing news about their health, as such news would have a negative impact on their children and their families.

“How can I go for the operation? If I went for the operation, my daughter cannot go to work. If she doesn’t work, she will not have an income and we will have no money to buy food. The last time I fell and fractured my arm, my daughter couldn’t work for half a year because she had to take care of me. She couldn’t get enough sleep. It’s not as simple as going for an operation. Who will take care of me after that? Who will earn the income?” (Chua, 66 years, Chinese, female)

“I don’t want to be a burden to others. When you are old, you become useless and a burden. Nothing but trouble to your own children. Nothing but trouble to society. I’d rather not live to 90 years old. Quickly come, quickly go, that’s the best.” (D, 88 years, Indian, female)

The second subtheme was related to a desire for independence. The elderly living alone viewed needing help as a sign of dependence and measured their self-worth based on the ability to live independently. Such independence was not limited to functional abilities but also included financial independence. It is possible that they perceived the need for help as losing independence and, with that, a loss of self-esteem and self-worth as well.

“I am just one person, there are many others who need help more than me. If I can walk, I will walk myself. There is no need to trouble anyone. A person, whilst living, should not always rely on others.” (D, 88 years, Indian, female)

“Some people feel that public assistance is a good thing. I do not envy them. It is desperation and I do not like that mindset. I would rather depend on myself and remain poor than rely on the nation to support me.” (Wong, 75 years, Chinese, male)

“The social worker asked me if I wanted to apply for financial assistance. They could give me $500 a month. My salary is little, but if I am frugal, I can get by. At my age, I do not have much to spend on. I told them until I really have no job and no choice, then I will rely on the government.” (Chua, 66 years, Chinese, female)

Theme 5 was the mismatch between perceived needs and services. Overall, we found that there was a mismatch between the perceived needs of elderly persons living in one-room rental flats and the healthcare services available in the community. Availability of services did not translate into optimum usage, because not all of the elderly were able to match their needs with the services provided.(14)

The first subtheme was a perceived lack of medical expertise by community healthcare providers. We identified that most elderly persons with complex medical condition(s) chose to see their regular doctors at the hospital for continuity of care. They also expressed greater trust in the quality of the hospital rather than community care. In addition, most participants interviewed preferred not to switch healthcare providers, as they believed that other doctors did not have a thorough understanding of their medical condition(s).

“Each time I go to the polyclinic, the doctors would say, ‘If it is a problem concerning your heart, go straight to the A&E.’ They said even if I came here, they would still send me to the A&E. So these days, I do not go to the polyclinic anymore. It is faster for me to go straight to A&E.” (Chua, 66 years, Chinese, female)

“The doctors in the polyclinic are always different. What if I suddenly turn ill, they would not know how to handle me. It is better that I go straight to the hospital when I am sick. My doctor knows my condition well and knows what to do with me.” (Leong, 81 years, Chinese, male)

Additionally, there was poor understanding of the importance of slow stream rehabilitation, the second subtheme. Among the elderly who had experience with post-discharge care after an acute hospital stay, some felt the activities at community hospitals were too mundane and not what they expected of ‘rehabilitation’. Many felt that they did not require an extended duration of stay at a community hospital following discharge, as the activities did not make a significant difference to their recovery.

“The exercises there (community hospital) are so childish. They ask you to wash a few pieces of clothes and boil a kettle of water. If that is the case, then isn’t every family doing ‘therapy’ everyday? One does not even perspire doing these things and yet they call it ‘exercise’.” (Wong, 75 years, Chinese, male)

“She (occupational therapist) told me to stand up and sit down. Take the beanbag high, put the beanbag low. Take the baju (hospital clothes) and fold it. I mean this is such an easy task! Even children can do it! Why do they make an old lady like me do such things?” (D, 88 year, Indian, female)

A possible reason for the disconnect could be insufficient explanation and health promotion by healthcare providers and allied health workers before and upon discharge from the acute hospitals. Patients with low health literacy may also have difficulty understanding the role of rehabilitation in preventive health.

DISCUSSION

In this study, out of 11 participants, seven listed their health as ‘good’ and three as ‘fair’. None of the participants felt their health was ‘poor’. Such perceptions of health status may provide them with a sense of well-being and comfort, and lead them to self-manage symptoms rather than seek medical consultation. Most of the participants whom we interviewed gauged their wellness based on physical symptoms. Hence, being healthy meant being symptom-free or having the ability to self-manage these symptoms. They sought medical consultation only when physical symptoms became more serious and did not resolve with self-management strategies.

Accessibility of financial assistance schemes (Theme 1) and perceived high costs of care (Theme 2) greatly influenced the respondents’ decision to use community healthcare services. In a Singapore study by Wong and Verbrugge that explored coping strategies among a sample of 19 elderly Singaporeans living alone, it was found that healthcare costs were the biggest contributor to financial instability. Among the patients on PA, 47% cited depletion of CPF savings due to medical bills as the main reason they were on PA.(15)

Although Singapore has many types of financial assistance schemes that offer an array of coverage and benefits, the application process can be complex and is often governed by strict eligibility criteria. For example, to be eligible for PA – where successful applicants receive a monthly payout for basic living expenses, free healthcare, hygiene consumables and medical treatment at all polyclinics and government/restructured hospitals – applicants must have no/little means of income with no/little family support and be unable to work due to old age, illness or disability.(16) Even if a financially needy elderly person automatically qualifies for subsidies from national auto-inclusion schemes (e.g. PG card), there is poor understanding on where and how these cards can be used. The outreach of nationwide publicity exercises to this particular group of elderly appears to be insufficient.

Faced with financial constraints, the decision to seek medical consultation is guided by the perceived seriousness of the medical illness at hand and is often a last resort after unsuccessful attempts at self-management of symptoms. Most of the elderly we interviewed had developed various strategies to cope with their healthcare needs. Use of over-the-counter medications, dietary interventions, TCM and exercise/Qigong were some of the more common coping strategies (Theme 3).

When these elderly persons decide to seek medical consultation, they may choose to visit the emergency department of acute hospitals rather than primary care clinics in the community.(17) We postulate several reasons for this. Firstly, large patient volumes and long waiting times at polyclinics may lead them to turn to the A&E as the first port of call to seek help (Subtheme 1b). Secondly, the treating physician’s lack of familiarity with the patient’s medical condition(s) may be a valid concern. As pointed out by Leong, an 81-year-old Chinese man, patients prefer to have the same healthcare provider at every follow-up visit. However, this may not always be possible at the polyclinics. Finally, as pointed out by Chua, a 66-year-old woman with chronic medical condition(s), the perceived lack of expertise of community healthcare providers to handle complex illnesses may also result in the elderly visiting hospital specialists rather than seeking help in the community (Subtheme 5a). Some of the elderly may not be aware that national electronic health records and electronic memorandums are available on an island-wide scale to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and handover of care from the hospitals to the polyclinics.

Such imbalances in healthcare utilisation are in keeping with findings from both local and international studies in patients of low socioeconomic status, which show a tendency for use of more acute hospital care and less primary care services.(6,14,17) These studies consistently report relative underuse of primary care and overuse of hospital-based care among patients of low socioeconomic status and residents of public rental housing. There is a bigger role for education and outreach, and for community healthcare providers to align their care to better match the needs of this group of elderly.

Finally, our findings highlight a gap to be filled by multidisciplinary teams to improve communication and promote understanding regarding the role of slow stream rehabilitation to help integrate the elderly back into the community. It is important to ensure that the elderly partake in collaborative goal-setting with their physiotherapists and occupational therapists before and upon discharge from the acute hospital. This is to ensure that they will be more engaged in the activities during their stay at the community hospitals.

The elderly living in one-room rental flats in Singapore are rooted in a distinct social context. Despite concerns that lack of social connectedness from living alone would have a negative impact on their physical well-being, they appear to be generally resilient and resourceful.(18,19) They value personal autonomy, self-reliance and independence, fear being a burden to their family or society, and have developed skills of self-management and self-monitoring of illness. While it is clear that financial and social barriers will continue to undermine their ability for self-efficacy in complex health behaviours, they pride themselves on their ability to live alone and find comfort in doing so. This philosophy of self-care suggests that the government’s policy of placing individual responsibility on health has been successful.

This study was not without limitations. Firstly, as some of the elderly interviewed were reticent, we had to use many probes to engage them. We minimised this by conducting the interviews in the privacy of their homes and restricting the number of interviewers to two persons. Secondly, our participants were recruited only from Chin Swee residential estate, which houses one-room public rental flats. However, this sample would be representative of other at-risk elderly residing in other public rental housing, as the demographic profiles and socioeconomic status of residents in other rental flats would be similar. Finally, the participants in this study were mostly Chinese. There was only one Indian participant and no Malay participant. This is largely because of our strict inclusion criteria, which limited participants only to elderly people who could speak either English or Mandarin. This issue arose due to the language limitations of the researchers for the purpose of translation and transcription of the raw data. In the study area (i.e. Chin Swee residential estate), it was also noted that the majority of residents are Chinese. It is hoped that with more resources, we can incorporate interviewers and coders who are fluent in other languages and dialects in future studies.

In conclusion, we identified five major themes that influence the health-seeking behaviour of at-risk elderly living alone in public rental housing in Singapore, namely accessibility of healthcare services and financial assistance schemes; perceived high costs of care; self-management; self-reliance; and mismatch between perceived needs and services. So far, interventions aimed at improving healthcare provision in the community of the elderly living alone have proven more difficult than anticipated, because ageing is an individualised process with health-seeking behaviour influenced by socioeconomic status, health literacy and personal values. There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to providing for the biopsychosocial needs of the elderly who live alone in one-room rental flats.(18,19) Our findings from this study have implications for policies and models of healthcare delivery that are designed to improve the health literacy and social integration of this group of elderly living alone. Finally, more needs to be done to champion the role of slow stream rehabilitation post discharge from acute hospitals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Statistics Singapore. Population Trends. 2015. [Accessed September 23 2018]. Available at: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/population-trends .

- 2.Chan A. Singapore's Changing Age Structure:Issues and Policy Implications for the Family and State. In: Tuljapurkar S, Pool I, Prachuabmoh V, editors. Population, Resources and Development:Riding the Age Waves. Vol. 2001. Springer Netherlands; pp. 221–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goh O. Successful ageing:a review of Singapore's policy approaches. [Accessed September 23 2018]. Available at: https://www.csc.gov.sg/articles/successful-ageing-a-review-of-singapore%27s-policy-approaches .

- 4.Low LL, Win W, Ng MJ, et al. Housing as a social determinant of health in Singapore and its association with readmission risk and increased utilization of hospital services. Front Public Health. 2016;4:109. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, et al. Post-discharge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist. 2008;48:495–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low LL, Tay WY, Ng MJ, et al. Frequent hospital admissions in Singapore:clinical risk factors and impact of socioeconomic status. Singapore Med J. 2018;59:39–43. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2016110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post-hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:283–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2571-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low LL, Liu N, Wang S, et al. Predicting 30-day readmissions in an Asian population:building a predictive model by incorporating markers of hospitalization severity. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng TP, Jin A, Feng L, et al. Mortality of older persons living alone:Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:126. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0128-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health Singapore. Chronic Disease Management Programme (CDMP) [Accessed September 23 2018]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/policies-and-legislation/chronic-disease-management-programme-(cdmp)

- 11.Ministry of Social and Family Development, Singapore. Schemes and Subsidies 2018. [Accessed September 23 2018]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/cost-financing/healthcare-schemes-subsidies .

- 12.Teo P, Chan A, Straughan P. Providing health care for older persons in Singapore. Health Policy. 2003;64:399–413. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silver Pages Singapore. Public Assistance. 2019. [Accessed August 24 2019]. Available at: https://www.silverpages.sg/financial-assistance/Public%20Assistance .

- 14.Wee LE, Lim LY, Shen T, et al. Choice of primary health care source in an urbanised low-income community in Singapore:a mixed-methods study. Fam Pract. 2014;31:81–91. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmt064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong YS, Verbrugge LM. Living alone:elderly Chinese Singaporeans. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2009;24:209–24. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teo P. Health care for older persons in Singapore:integrating state and community provisions with individual support. J Aging Soc Policy. 2004;16:43–67. doi: 10.1300/J031v16n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1196–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality:a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227–37. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WK. The poor in Singapore:issues and options. J Contemp Asia. 2001;31:57–70. doi: 10.1080/00472330180000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]