Abstract

Previous research has suggested the negative relationship between self-esteem and conspicuous consumption since conspicuous consumption is aimed to gain social recognition and signal status. However, it has not been much explored how this relationship holds depending on social classes. We propose subjective social class will moderate the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption. We also hypothesize the mediating roles of social dominance orientation and life satisfaction in the proposed moderation effect. By conducting the survey with the American sample, we tested these predictions. In Study 1, we showed that the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption appeared only among high subjective social class individuals. In Study 2, we replicated Study 1 and further demonstrated that social dominance orientation and life satisfaction respectively mediated the interactive effect of subjective social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption. The results suggest that among individuals who perceive themselves to be in a high social class, a low level of social self-esteem is conducive to conspicuous consumption. The theoretical implications and limitations of the present investigation are discussed.

Keywords: Social class, Conspicuous consumption, Self-esteem, Social self-esteem, Social dominance orientation, Life satisfaction

social class; conspicuous consumption; self-esteem; social self-esteem; social dominance orientation; life satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Conspicuous consumption refers to a display of overspending money on goods or services to signal one's wealth and social status (Veblen, 2009). People tend to spend a lot on products for a reason to get social recognition, enhance self-image, and signal prestige to others (Shukla, 2008). Individuals in a high social class use conspicuous consumption as a means to differentiate themselves from other social groups, particularly individuals in a low social class (Veblen, 2009). Indeed, the higher people perceive their social class either subjectively or objectively, the more they want status and material success (Wang et al., 2020), which supports high-class individuals' conspicuous consumption. In return, conspicuous consumption such as luxury brand consumption is perceived as high status (Desmichel et al., 2020).

Although individuals in a high social class are inclined to conspicuous consumption in general, the potential contributor of conspicuous consumption among high social class individuals has not been much investigated. When feeling a lack of confidence in the social situation, those who perceive to belong to a high social class would experience their desire for social recognition and acceptance thwarted. Since conspicuous consumption is directed to obtain social recognition and acceptance from one's reference group and seek social approval (Neave et al., 2020; O'cass & McEwen, 2004), the lack of social acceptance or respect experienced among high social class individuals may instigate a need for social acceptance and status via conspicuous consumption. Particularly, the sense of low self-esteem can be a precursor of conspicuous consumption given the evidence for the negative relationship between perceptions of self-worth (e.g., self-esteem) and conspicuous consumption (Kim and Gal, 2014; Mandel et al., 2017). For example, in facing self-threat, people engage in conspicuous consumption as a means to compensate their threatened self (Pettit and Sivanathan, 2011; Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010). Similarly, when individuals feel powerless, their willingness to pay for products that can be status symbols is increased (Rucker and Galinsky, 2008) and prefer conspicuous consumption of luxury brands (Koo and Im, 2019). Those with vulnerable narcissism tend to have low self-esteem and engage in conspicuous consumption out of motivation to reduce their negative self-concept (Fastoso et al., 2018) and to seek social approval (Neave et al., 2020). While these findings converge to the negative relationship between conspicuous consumption and self-esteem, it has remained unknown how strongly this relationship will persist depending on one's social class.

To extend previous literature showing consumption for status signaling among high-class individuals (Wang et al., 2020) and the link between self-worth and conspicuous consumption (Dommer et al., 2013; Mandel et al., 2017; Neave et al., 2020; Pettit and Sivanathan, 2011; Zheng et al., 2018), this research aims to examine how subjective social class moderates the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption. Specifically, building on the literature on social class (Belmi et al., 2020; Carey and Markus, 2016; Stephens et al., 2012), self-esteem (Heatherton and Polivy, 1991; Leary et al., 1995; McCain et al., 2015), and compensatory consumption (Kim and Gal, 2014; Mandel et al., 2017; Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010), we propose that individuals in a high class have a greater tendency to engage in conspicuous consumption when experiencing low social self-esteem than individuals in a low class. And further for the underlying mechanism, we hypothesize that social dominance orientation and life satisfaction respectively mediate the proposed relationship between social self-esteem, social class, and conspicuous consumption. Two studies were conducted to test the moderation by the social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption, and to examine the underlying mechanism with the proposed mediators.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Self-esteem and conspicuous consumption

Self-esteem is highly relevant to perceptions of social self and social confidence (Leary et al., 1995). Self-esteem reflects one's social status as well as social inclusion (Mahadevan et al., 2019a). Indeed, low self-esteem is associated with a sense of feeling socially excluded (Leary et al., 1995) as well as perceiving low status (Mahadevan et al., 2019b). Accordingly, those with low self-esteem place great importance of extrinsic aspirations regarding one's image, popularity, and wealth (Elphinstone and Whitehead, 2019) and are highly concerned with their self-presentation in social contexts (Baumeister et al., 1989). As a result, extant literature shows the negative relationship between self-esteem and conspicuous consumption. When people are socially excluded from the close relationship (e.g., friends), they experience weakened self-esteem, which in turn makes them prefer conspicuous consumption (Liang et al., 2018). Those with low self-esteem prefer brands such as luxury brands that can signal high social status in order to ensure their group inclusion in the future even when they experience a sense of belonging (Dommer et al., 2013). Also, among people with low income who tend to have low global self-esteem, their consumption decisions are driven by motives to signal status (Sivanathan and Pettit, 2010). When people are ignored, they prefer conspicuous logos of a high-end clothing brand more (Lee and Shrum, 2012). Those with covert narcissism have fragile self-perception and thus seek luxury brands to compensate their low self-esteem (Fastoso et al., 2018) and to earn social approval (Neave et al., 2020). Together, previous research suggests self-esteem is related to conspicuous consumption in a compensatory manner.

While prior work on self-esteem and conspicuous consumption has mostly relied on global self-esteem, which reflects global attitudes toward self, for a specific relevant domain of interest, the predictive power of specific self-esteem is greater than global self-esteem (Bozorgpour and Salimi, 2012; Mackinnon et al., 2015; Rosenberg et al., 1995; Rubin and Hewstone, 1998). Among various specific self-esteem aspects social self-esteem is considered as the most relevant to interpersonal behaviors regarding public image and self-presentation (Baumeister et al., 1989; Heatherton and Polivy, 1991). Since conspicuous consumption is directed towards gaining social approval and signaling status, this research focuses on the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption in further investigating the role of social class.

2.2. Role of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption

Social class perception is dynamically constructed by social experiences obtained through objective social class (Phillips et al., 2020). Hence, a measure of the subjective social class shows the most strong and reliable relationships with variables regarding social confidence such as competence than other social class measures (Belmi et al., 2020). This suggests that the subjective perception of one's social class is adequate in explaining behaviors related to social motives. Thus, we examined how high and low subjective social classes diverge on conspicuous consumption in response to low social self-esteem. Since social self-esteem is most relevant to one's self-image in public and social inclusion (Heatherton and Polivy, 1991), a low level of social self-esteem would be closely related to compensatory reactions to gain positive self-worth in the social domain. According to the compensatory consumer behavior model, when people experience self-discrepancies, they engage in compensatory consumption which can help them restore their self-discrepancies (Mandel et al., 2017). However, such a compensatory motive might be more pronounced among high social class individuals due to the differences between high versus low class. Social class as a social rank in a given society can be a source of social power and status in terms of capability to exert influence on others and to receive respect from others (Dubois et al., 2015). Moreover, high social class individuals tend to have a stronger desire to have prestige, dominance, and high rank in a society, compared to low class individuals (Belmi et al., 2020). However, for individuals in a high social class, a low level of social self-esteem which suggests a low self-evaluation in social contexts may make them perceive a discrepancy from expectations related to a high social class.

High and low class individuals might differ in their response to low social self-esteem due to their contextual differences between different classes (Stephens et al., 2012). Individuals with relatively high social class are influenced by the environment that allows abundant resources for agency and control, and thus facilitates independence in the social contexts (Stephens et al., 2012), which allow them to strive for their own goals with individualistic focus (Kraus et al., 2012). By contrast, individuals with relatively low social class (e.g., working class) are shaped by the environment that imposes constraints due to limited resources, and thus facilitates interdependence in the social contexts (Carey and Markus, 2016; Stephens et al., 2012). As a result, high class individuals report to have a higher sense of control than low class counterparts (Kraus et al., 2009; Lachman and Weaver, 1998). Due to the different implications about one's own agency and controllability based on experiences from the given environment, low social class individuals tend to find explanations of social events based on contextual factors whereas high class individuals tend to focus on individual factors (Kraus et al., 2009; Lee, 2018). Hence, high class individuals who tend to hold relatively high agency and efficacy of their own actions might believe their consumption behavior can be an effective means to compensate their low social self-esteem more than low class individuals who do not hold the strong agentic beliefs and a sense of control. In other words, social self-esteem will be more strongly related to conspicuous consumption among the high class than the low class.

Since social self-esteem is most relevant to one's self-image in public and social inclusion (Heatherton and Polivy, 1991), a low level of social self-esteem would be closely related to high social class' compensatory reactions to gain their positive self-worth in the eyes of others. Indeed, previous research has shown conspicuous consumption can be adopted as a means to support and express their social standing. Since behaviors signaling social power and status can increase self-esteem (Wojciszke and Struzynska–Kujalowicz, 2007), conspicuous consumption that can signal social power and status (Dubois et al., 2021) can be viewed as a means to restore self-esteem. For example, using products that carry a visible logo of a luxury brand is used to signal one's dominance (Panchal and Gill, 2019) and to compensate a sense of low social power (Koo and Im, 2019). Also, when social inclusion is high, one with a low level of self-esteem exhibits high attachment towards brands that signal high status as signaling with such brands may facilitate social inclusion in one's valued social group (Dommer et al., 2013). Similarly, when high social class individuals have a low level of social self-esteem, conspicuous consumption such as buying luxury brands may be viewed as a viable means to obtain one's social acceptance and respect from others. When people perceive a lack of social influence (e.g., socially powerless), they tend to prefer status-signaling products such as luxury products (Rucker and Galinsky, 2008) and products carrying large brand logos (Koo and Im, 2019).

Thus, we predict that the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption would be pronounced among individuals who perceive to be in a high social class.

H1

The relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption will be moderated by social class. Specifically, the negative relationship between them will be pronounced among those with high social class perceptions.

3. Study 1

We conducted study 1 to investigate the proposed moderating role of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption (H1).

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants

We recruited 301 American residents (145 women and 156 men; Mage = 36.34 years except for one participant who indicated an impossible value, SD = 10.36; age range from 19 to 68 years) from the Amazon Mechanical Turk in exchange for monetary compensation (40 cents). The Amazon Mechanical Turk is known to be a reliable pool for the data collection (Coppock, 2019; Kees et al., 2017; Peer et al., 2014). Given that the previous investigation on state self-esteem and conspicuous consumption has often sampled American participants, we targeted to sample American participants in order to ensure the compatibility of our findings with American samples adopted in the previous research studies regarding state self-esteem (Lewis, 2020; Sarfan et al., 2019), social class (Palma et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2020), and conspicuous consumption behavior (Boonchoo and Thoumrungroje, 2017; Keech et al., 2020; Koo and Im, 2019; Segal and Podoshen, 2013).

In all studies (studies 1 and 2), informed consent was made by all participants. No personally identifiable information was collected in these studies. All the procedure was approved by the ethics committee, Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Open University of Hong Kong for ethical review regarding human research. All the procedure and method comply the COPE ethics guideline. In both studies, we adopted a convenient sampling method as the data was obtained from the online panelists. In all studies, they were allowed to stop at any point of the study while being informed that the compensation was ensured only upon the completion of the study.

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.2.1. State self-esteem scale

We measured people's state social self-esteem by using the Heatherton and Polivy (1991)'s 20-item state self-esteem scale (α = .910) as it is adopted for both college student as well as non-student adult sample (Greitemeyer, 2016). This scale consists of three sub-scales: social (α = .925), performance (α = .792), and appearance (α = .775). All the subscales and the total scale revealed satisfactory reliability. The details of specific operational definition and measurement of all the measured variables of all studies are found in Supplementary materials (Tables A and B).

3.1.2.2. Conspicuous consumption

We adopted the five items for conspicuous consumption (e.g., “cars,” “shoes,” “nice dinner with friends,” “new mobile phone,” and “watches or jewelry”), following previous literature (Sundie et al., 2011; Wang and Griskevicius, 2013) as such items are easily visible to others in social interactions (Charles et al., 2009) and adopted as status signals (Desmichel et al., 2020; Dubois et al., 2021). We asked, “Compared to your peers, how much money would you spend on _____” on a 9-point Likert scale (1 = much less than the average, 9 = much more than the average). We created a composite measure of conspicuous consumption by averaging the scores of five items (α = .908).

3.1.2.3. Subjective social class

To measure people's subjective social class perception, we used the 6-item scale (α = .978) from Belmi and Neale (2014) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

3.1.2.4. Others

We also collected demographic information including race, annual household income, and educational attainment. The demographic information of participants of all studies is summarized in the Supplementary materials (Table C).

3.2. Results

The descriptive statistics and correlations of measured variables are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of variables in Study 1.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SSE social subscale | 23.3 | 7.67 | |||||

| 2 | SSE performance subscale | 26.2 | 5.67 | .79∗∗∗ | ||||

| 3 | SSE appearance subscale | 19.6 | 5.13 | .34∗∗∗ | .38∗∗∗ | |||

| 4 | SSE total scale | 69.1 | 15.3 | .91∗∗∗ | .90∗∗∗ | .64∗∗∗ | ||

| 5 | Subjective social class | 3.54 | 1.93 | −.40∗∗∗ | −.28∗∗∗ | .44∗∗∗ | −.15∗∗∗ | |

| 6 | Conspicuous consumption | 4.86 | 1.98 | −.53∗∗∗ | −.33∗∗∗ | .32∗∗∗ | −.28∗∗∗ | .75∗∗∗ |

Note. n = 301. SSE: State self-esteem. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

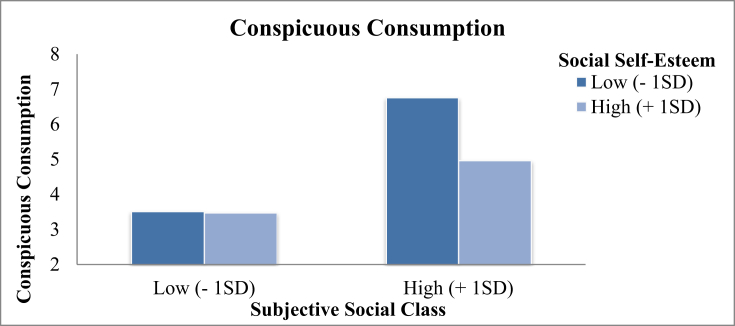

To test our main prediction (H1), we adopted the linear regression model which has been used by previous studies that examined the interaction effects (Abbasi, 2019; K. Lee, 2018a, b; Uziel and Cohen, 2020; Walters, 2018). Also, the regression models are appropriate in comparing the predictive power of different predictors (Borráz-León and Rantala, 2021; Wood and Gray, 2019) as we also intended to compare the different types of self-esteem to see if social self-esteem is most relevant to conspicuous consumption. We regressed conspicuous consumption on social self-esteem, subjective social class, and their interaction. All measured predictors were standardized to avoid multicollinearity (Jaccard et al., 2003; Lachman and Weaver, 1998). The regression revealed that subjective social class had a significant main effect, b = 1.18, t(297) = 16.11, p < .001, and the significant main effect of social self-esteem, b = −.46, t(297) = −6.26, p < .001, which was qualified by a significant subjective social class by social self-esteem interaction, b = −.44, t(297) = −6.66, p < .001 (see Figure 1). To further probe the significant interaction, we conducted the simple slopes analysis (Aiken et al., 1991), at both the high and low levels of subjective social class (Uziel and Cohen, 2020). This intends to test our prediction for the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption to be more pronounced among the high class individuals than among the low social class individuals (H1). Indeed, the effect of social self-esteem was significant among those with high subjective social class (1 SD above the mean of subjective social class, +1 SD), b = −.89, t(297) = −9.97, p < .001, in support of H1. This suggests that among those who believed they were in high social class, the lower their social self-esteem, the higher conspicuous consumption, suggesting the compensatory mechanism. When high social class individuals had low (vs. high) social self-esteem, their conspicuous consumption was higher. By contrast, the effect of social self-esteem was not significant among those who perceived their social class as low (1 SD below the mean of subjective social class, −1 SD), b = −.02, t(297) = −.16, p = .872. This suggests that among low social class individuals, low self-esteem did not make them pursue conspicuous consumption more.

Figure 1.

Conspicuous consumption as a function of social self-esteem and subjective social class in Study 1. Note. The values are estimated at 1SD below/above the mean of the social self-esteem scale and at 1SD below/above the mean of the subjective social class scale, respectively.

Study 1 provides initial evidence for the moderating role of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption. The negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption was apparent only at a high level of subjective social class. This suggests that conspicuous consumption occurs in a compensatory manner. Only those who were in a high social class responded to low social self-esteem by increasing conspicuous consumption but those who were in a low social class did not change their conspicuous consumption due to low social self-esteem. Also, while this compensatory pattern appeared for all sub-factors of self-esteem and the total self-esteem scale, social self-esteem revealed the most pronounced relationship with conspicuous consumption.

Although the proposed relationships were observed in Study 1, there were several limitations. First, although we measured conspicuous consumption with the items used in previous research, the questions do not directly ask one's motivation to show off or signal their status through consumption. Rather, the measure depends on the assumption that spending more on publicly visible products (e.g., cars, watches) should mean conspicuous consumption. However, some might spend more in these product categories due to a different motive from the signaling motive. Hence, in the following study, we aimed to address this limitation by additionally having a direct measure of the social motive of the conspicuous consumption and testing whether the interactive effect is consistently observed when the consumption motivation is measured. Also, our theorizing assumes that the temporary harm in state social self-esteem facilitates conspicuous consumption as a means to recover social self-esteem, and thus the act of conspicuous consumption should be motivated by social motivation, not the chronic materialistic pursuit. However, Study 1 did not clearly rule out the possibility that one's chronic materialism instead of social motivation, might influence the response to the conspicuous consumption scale. The following study will address these concerns by adopting the measures of social motivation and trait materialism in addition to the conspicuous consumption scale.

Furthermore, while the finding of Study 1 supported our hypothesis, it did not provide evidence for the process regarding how social self-esteem and social class interactively influenced conspicuous consumption. To uncover the underlying process of the moderation effect in Study 1, we further reviewed the literature and identified several mediators. The hypotheses with the mediators were developed as in the following before we conducted Study 2.

4. Underlying process of the interactive effect of social self-esteem and social class

Given the support of the hypothesized effect of social self-esteem and social class on conspicuous consumption, we aim to delve into how the effect of social self-esteem is pronounced particularly among those with high social class. The several processes in parallel may contribute to the proposed relationships between social self-esteem, subjective social class, and conspicuous consumption. Specifically, we propose how social dominance orientation and life satisfaction might mediate these relationships.

4.1. Social dominance orientation

First, social dominance orientation (SDO) reflects people's favorable attitudes towards social hierarchy (Pratto et al., 1994). People from high-status groups (e.g., Caucasians in the States) tend to exhibit higher SDO than their counterparts from low-status groups (e.g., African Americans in the States) (Sidanius et al., 2000) presumably due to the need to justify social inequality via favorable attitudes towards social hierarchy (Oldmeadow and Fiske, 2007). This suggests people in a high subjective social class would have relatively high SDO. However, when social self-esteem is taken into account, the role of social class on SDO would become intricate. As discussed above, while one's social class suggests one's social status and rank, warranting interpersonal respect (Dubois et al., 2015), a low level of social self-esteem would create a sense of discrepancy, particularly among high social class individuals. To cope with the discrepancy between their social class perception and social self-esteem, high-class individuals may be motivated to elevate their SDO. Indeed, the positive relationship between system justification and social dominance orientation is stronger among high-status individuals (Vargas-Salfate et al., 2018). This suggests that when motivated to justify their desire for status and prestige, social dominance orientation is likely to be bolstered among the high class. Furthermore, as a result of endorsing SDO, high social class individuals would engage more in conspicuous consumption for signaling one's social status and prestige. SDO is related to the endorsement of the worldview to see the world as a competitive jungle, which includes the importance of wealth and luxury in one's life (Leone et al., 2012). That explains why those with high SDO have a strong interest to consume luxury products from their symbolic meanings associated with social status (Yu and Sapp, 2019). Thus, we propose the relationship between a low level of social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption among high subjective social class individuals will be explained by SDO. In other words, we examine if SDO mediates the interactive effects of subjective social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption.

H2

The interactive effect of social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption will be mediated by social dominance orientation.

4.2. Life satisfaction

Second, self-esteem is positively related to life satisfaction, which reflects a global assessment of one's quality of life (Diener et al., 1985). Also, social class–measured either as objective or subjective– is positively related to subjective well-being such as life satisfaction (Islam et al., 2009) because high (vs. low) social class tend to feel a higher sense of control (Lachman and Weaver, 1998) and because of their status (Yu and Blader, 2020). While each of self-esteem and social class is positively related to life satisfaction, their interactive effect might be nuanced. Previous research has shown that the higher aspirations one has for income, the smaller contribution increasing income made to life satisfaction (Bruni and Stanca, 2006). Similarly, when people are surrounded by frequent presentations of other's luxurious possessions in the neighborhood, their income satisfaction declines (Winkelmann, 2012). When people become concerned with self-promotion in the social context such as using the social media, their conspicuous consumption is also increased (Taylor and Strutton, 2016). This suggests that high social class individuals may have only small incremental benefits from increased self-esteem on life satisfaction but rather low social class individuals may reap a greater benefit from increase self-esteem on life satisfaction. Moreover, high social class individuals tend to report higher life satisfaction because of higher status (Yu and Blader, 2020), which suggests that dampened status perception via low social self-esteem would reduce life satisfaction among the high class. Instead, given that increasing conspicuous consumption does increase life satisfaction (Brown and Gathergood, 2020; Wu, 2020), those with high subjective social class but a low level of social self-esteem may try to take an advantage of conspicuous consumption. Hence, we examine the mediating role of life satisfaction.

H3

The interactive effect of social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption will be mediated by life satisfaction.

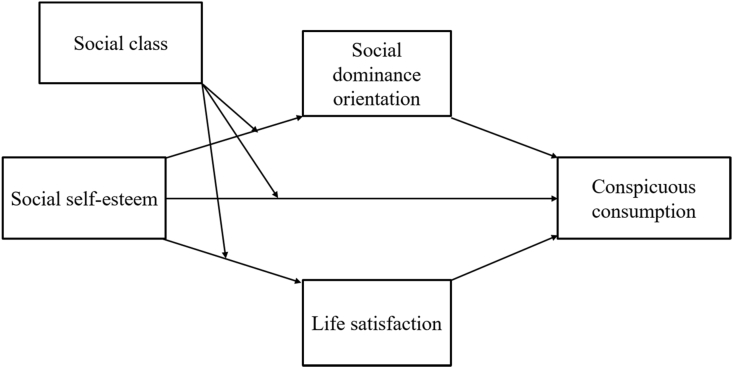

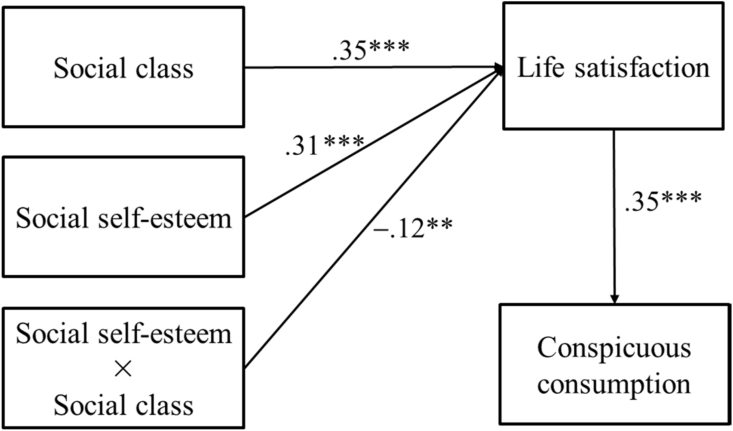

In summary, we propose the following conceptual model regarding the mediating roles of social dominance orientation and life satisfaction in the relationship between subjective social class, social self-esteem, and conspicuous consumption (see Figure 2). Thus, in Study 2, we test these proposed mediating roles of social orientation and life satisfaction (H2 and H3) in addition to the interaction between social class and social self-esteem (H1).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model. Note. The moderating role of social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption (H1) was tested in both Studies 1 and 2. The mediating roles of social dominance orientation and life satisfaction in the moderation (H2 and H3) were tested in Study 2.

5. Study 2

In Study 2, we aim to replicate the finding of Study 1 with additional measures and to find the process underlying the relationships of social self-esteem, subjective social class, and conspicuous consumption. We introduced additional measures (e.g., the social motivation of consumption and materialism) to see if conspicuous consumption was momentarily influenced among the high class due to social self-esteem but not due to the increased materialistic pursuit in general. Furthermore, we tested if social dominance orientation and life satisfaction may mediate the interactive effect of social self-esteem and subjective social class (H2 and H3).

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants

Data was collected from 404 American residents (102 women and 295 men; Mage = 34.69 with age and gender information of seven participants missing, SD = 13.08; age range 19–57 years) took part in an online study from the Prolific panel in exchange for monetary compensation (87 cents). The Prolific platform has been shown to have a good reliability for the data collection for academic research (Palan and Schitter, 2018). We purposely used a different online platform from Study 1 to ensure the robustness of the findings across different platforms for participant recruitment despite sampling from different platforms.

5.1.2. Measures

5.1.2.1. State self-esteem

Identical to Study 1, we adopted the Heatherton and Polivy (1991)'s 20-item state self-esteem scale (α = .932). The three subscales were constructed: social (α = .711), performance (α = .845), and appearance (α = .549). Except for the appearance subscale, other subscales and the total scale showed satisfactory reliability.

5.1.2.2. Conspicuous consumption measures

We adopted the same five items for conspicuous consumption (α = .790) as in Study 1. We added 4-item social motivation for consumption scale (α = .857), which focuses on motivations of one's conspicuous consumption (Chung and Fischer, 2001; Segal and Podoshen, 2013). Each item (e.g., “Before purchasing a product, it is important to know what brands or products to buy to make a good impression on others.“) was asked in a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

5.1.2.3. Subjective social class

We again used the same subjective social class 6-item scale (α = .953) from Belmi and Neale (2014).

5.1.2.4. Process measures

We also collected the additional scales to test the underlying process: the 8-item social dominance scale (α = .871), called SDO7 (Ho et al., 2015) was adopted to measure people's social dominance orientation tendency. Participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale to each of individual statements (1 = strongly oppose, 7 = strongly favor). The 9-item material values scale (α = .805) (Richins, 2004) was used to capture materialism on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The 5-item satisfaction with life scale (α = .911) was used to measure life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985). The items were responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Lastly, we collected the same set of demographic information as in Study 1.

5.2. Results

The descriptive statistics and correlations of measured variables are reported in Table 2. Given the two objectives of Study 2: (1) to replicate the moderation effects on the identical measure to study 1 as well as the additional measure of consumption motivation; (2) to test the proposed mediators in this moderation, the results of the moderation analysis are reported first and then the results of the moderated mediation analysis follow.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of variables in Study 2.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SSE social subscale | 22.4 | 6.69 | |||||||||

| 2 | SSE performance subscale | 24.7 | 5.69 | .74∗∗∗ | ||||||||

| 3 | SSE appearance subscale | 17.2 | 5.53 | .58∗∗∗ | .59∗∗∗ | |||||||

| 4 | SSE total scale | 64.3 | 15.6 | .90∗∗∗ | .89∗∗∗ | .82∗∗∗ | ||||||

| 5 | Subjective social class | 2.25 | 1.44 | .10∗ | .18∗∗∗ | .37∗∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | |||||

| 6 | Conspicuous consumption | 3.76 | 1.51 | .01 | .09 | .23∗∗∗ | .12∗ | .41∗∗∗ | ||||

| 7 | Social motivation for consumption | 2.32 | 1.07 | −.22∗∗∗ | −.15∗∗ | .14∗∗ | −.10∗ | .33∗∗ | .31∗∗∗ | |||

| 8 | Materialism | 2.96 | .74 | −.30∗∗∗ | −.17∗∗∗ | −.08 | −.22∗∗∗ | .16∗∗ | .36∗∗∗ | 40∗∗∗ | ||

| 9 | Life satisfaction | 3.62 | 1.53 | .36∗∗∗ | .46∗∗∗ | .59∗∗∗ | .53∗∗∗ | .37∗∗∗ | .20∗∗∗ | .11∗ | −.10∗ | |

| 10 | Social dominance orientation | 2.45 | 1.18 | −.04 | −.02 | .08 | .01 | .30∗∗∗ | .20∗∗∗ | .26∗∗∗ | .23∗∗∗ | .13∗∗ |

Note. n = 404. SSE: State self-esteem. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001.

5.2.1. Interactive effect of social self-esteem and subjective social class

First, we tested whether the moderating role of social class replicates in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption regardless of which measures of conspicuous consumption are tested. To analyze the interactive effect of social self-esteem and subjective social class, we conducted a separate regression analysis on each of the measured variables: conspicuous consumption, social motivation of consumption, materialism, social dominance orientation, and life satisfaction. In the regression model, conspicuous consumption was regressed on social self-esteem, subjective social class, and their interaction, same as the regression in Study 1.

5.2.1.1. Conspicuous consumption

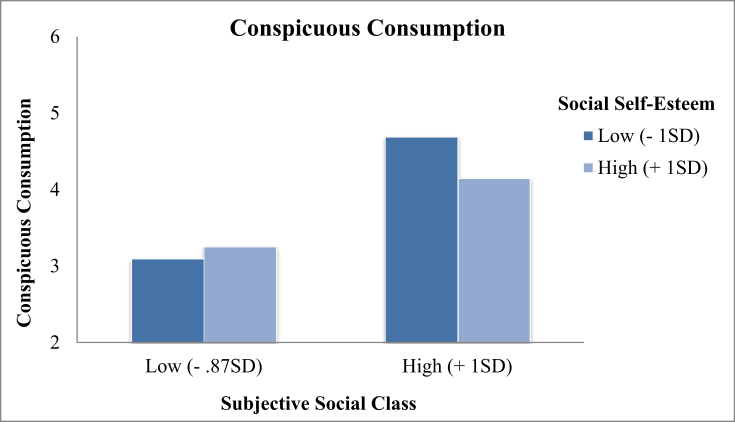

The regression analysis results showed the significant main effect of subjective social class, b = .64, t(400) = 9.21, p < .001, and the non-significant effect of social self-esteem, b = −.08, t(400) = −1.13, p = .258, which were qualified by the significant interaction between subjective social class and social self-esteem, b = −.19, t(400) = −2.72, p = .007 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conspicuous consumption as a function of social self-esteem and subjective social class in Study 2. Note. The values are estimated at 1 SD below/above the mean of each scale for social self-esteem while at .87 SD below the mean and 1 SD above the mean of subjective social class scale, respectively. This is due to the lowest value of the subjective social class scale corresponding to .87 SD below the mean of the scale.

Furthermore, the simple slopes analysis revealed that, the effect of social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption was significant among those who subjectively perceived to be in a high social class (+1 SD above the mean of subjective social class), b = −.30, t(400) = −2.57, p = .011, but not among those who subjectively perceived themselves as a low social class (.87 SD below the mean of subjective social class), b = .09, t(400) = 1.01, p = .312. The latter for the low social class was estimated at .87 SD below the mean of the subjective social class scale since the lowest value of the scale (1) corresponds to .87 SD below the mean of the scale. This replicates Study 1. Again, if people regarded themselves as a high social class, their social self-esteem was negatively related to conspicuous consumption. Replicating Study 1, among high social class individuals, low (vs. high) social self-esteem increases conspicuous consumption. This pattern is not apparent among those in a low subjective social class. Overall, the findings again support Hypothesis 1.

5.2.1.2. Social motivation of consumption

The results showed the significant main effect of subjective social class, b = .39, t(400) = 8.18, p < .001, and the significant effect of social self-esteem, b = −.30, t(400) = −6.09, p < .001. The interaction between subjective social class and social self-esteem was significant, b = −.14, t(400) = −2.89, p = .004. The simple slopes analysis showed that the negative relationship between social self-esteem and social motivation of consumption was larger among those who perceived to be high social class (+1 SD), b = −.44, t(400) = −5.96, p < .001, relative to the effect among those who perceived to be low social class (−.87 SD), b = −.17, t(400) = −2.86, p = .004. This suggests that among those who perceived themselves in a high social class, when they felt low social-esteem, they exhibited more social motivation of consumption. This result is complementary to findings with the conspicuous consumption measure by showing the underlying motive.

5.2.1.3. Trait materialism

We also tested if the interactive effect of social self-esteem and social class might appear on trait materialism. However, although the social self-esteem had a negative effect on materialism, b = −.23, t(400) = −6.67, p < .001, and the subjective social class had a positive effect on materialism, b = .14, t(400) = 3.97, p < .001, the interaction between social self-esteem and subjective social class was not significant, b = −.02, t(400) = −.49, p = .622. This suggests that increased conspicuous consumption driven by low social self-esteem is not due to the increased materialistic pursuit among the high class individuals.

Additionally, the same set of the moderation analysis was conducted on the proposed mediators respectively to see how these mediators change as a function of social class, social self-esteem, and their interaction (see the Supplementary materials).

5.2.2. Moderated mediation model

Second, we also tested whether the proposed mediators showed the indirect effects as hypothesized (H2 and H3). To test the moderated mediation, we used model 7 of PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) with 5,000 times of bootstrapping. The bootstrapping method provided by Hayes has been extensively adopted and accepted as a reliable method to test the indirect effect for the mediation analysis (Hayes, 2015; Meule, 2019; Valeri and VanderWeele, 2013; Wu and Jia, 2013). We tested SDO and life satisfaction for the mediating role in the interactive effect of social self-esteem and subjective social class on conspicuous consumption. Each scale was standardized.

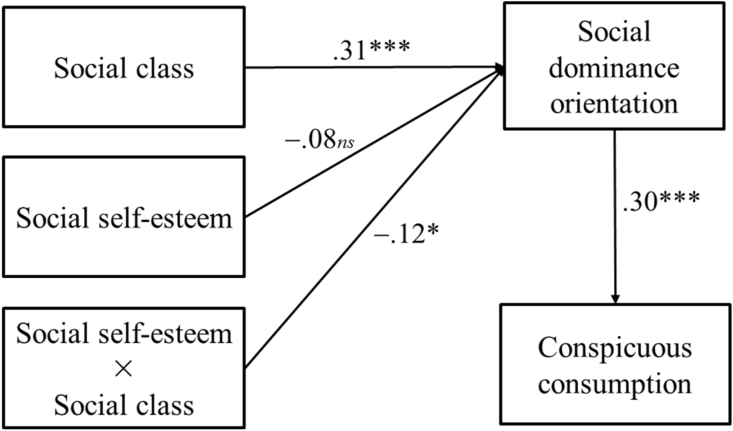

5.2.2.1. Social dominance orientation as a mediator

The indirect effect via SDO was significant (index of moderated mediation = −.04, SE = .02, 95% CIs [−.07, −.004]), which supports hypothesis 2 (see Figure 4). Specifically, the indirect effect of social self-esteem was significant at the high level of subjective social class (+1 SD; 95% CI [−.13, −.01]), but not significant at the low level (−.87 SD; 95% CI [−.03, .04]). This result suggests that the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption is explained by increased social dominance orientation via low social self-esteem, but this mechanism is evident only among the high social class, but not among the low social class.

Figure 4.

Moderated mediation analysis with social dominance orientation as mediator (Study 2). Note. ∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

5.2.2.2. Life satisfaction as a mediator

The indirect effect of social self-esteem via life satisfaction was also significant (index of moderated mediation = −.04, SE = .02, 95% CIs [−.09, −.01]), in support of hypothesis 3 (see Figure 5). The indirect effect was significant at both high (+1 SD; 95% CI [.02, .12]) and low (−.87 SD; 95% CI [.07, .24]) levels of subjective social class. This result suggests that social self-esteem had an indirect effect on conspicuous consumption via life satisfaction, which was moderated by social class. Specifically, the relationship between social self-esteem and life satisfaction becomes weakened among the high social class, compared to the relationship among the low social class. In other words, among the high class, relative to the low class, the contribution of social self-esteem to conspicuous consumption via life satisfaction was smaller.

Figure 5.

Moderated mediation analysis with life satisfaction as mediator (Study 2). Note. ∗p < .05; ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

Study 2 intended to replicate the findings in Study 1 with additional measures while testing the proposed mediators. As expected, Study 2 replicated the finding of Study 1 by showing the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption was moderated by subjective social class. This finding is complemented by the paralleled results in the explicit measure for the social motivation of consumption. Only high social class individuals showed increased conspicuous consumption upon lower social self-esteem, but low social class individuals did not exhibit the same pattern. Furthermore, we tested the mediating roles of life satisfaction and social dominance orientation respectively in this moderation effect. Both social dominance orientation and life satisfaction respectively mediated the moderation of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption.

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion of the current findings

The objectives of the present research were two-fold: (1) demonstrating the moderating role of subjective social class in the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption; (2) revealing the underlying mechanism of this moderation by testing social dominance orientation and life satisfaction as mediators. Concerning (1) the first objective, two studies provide the convergent evidence of the moderating role of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption. Both Studies 1 and 2 supported our prediction that among the high social class, low social self-esteem is related to high conspicuous consumption (H1). In addition, Study 2 reveals the compensatory mechanism of this relationship by showing the same interactive influence of subjective social class and social self-esteem on the social motivation of consumption, but not on trait materialism. Furthermore, regarding (2) the second objective of this research, this negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption among the high social class was successfully explained by the mediating roles of social dominance orientation and life satisfaction (H2 and H3). Low social self-esteem among the high social class heightened social dominance orientation, which increased conspicuous consumption. On the other hand, while low social self-esteem did not erode life satisfaction among the high social class as much as among the low social class according to the significant moderation by social class in the effect of social self-esteem on life satisfaction, the moderated life satisfaction increased conspicuous consumption in turn.

While the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption among the low class is not central to the current investigation, it is notable that the compensatory conspicuous consumption tendency is not pronounced as a result of low social self-esteem among the low class individuals. This might be related to their limited resources that may make them unaccustomed to resorting to consumption to compensate for their negative self-perceptions but rather used to finding an alternative way to recover their self-worth. Indeed, when feeling threatened by upward social comparison in the financial and professional domains, individuals become motivated to find meanings and values from their intangible achievements and relationships in their lives (Goor et al., 2020). It will be another interesting research avenue to examine how the low class individuals deal with an experience of feeling low social self-esteem.

We additionally explored if sociodemographic differences might play a role in the proposed relationship by examining the potential roles of gender, income level, education attainment, and race in both studies (see the Supplementary materials). However, none of them moderated the proposed effects, which suggests that our findings did not change depending on such sociodemographic differences.

6.2. Implications of the current findings

6.2.1. Relationship between subjective social class, social self-esteem, and conspicuous consumption

Although previous research has shown the negative relationship between self-esteem and conspicuous consumption, consistent with the compensatory behavior mechanism (Cui et al., 2020; Mandel et al., 2017), it has not been investigated whether the general compensatory mechanism of self-esteem may work the same for people from different social classes. While recent research studies rather focus on the heightened materialistic pursuit of a low social class (Charles et al., 2009; Christen and Morgan, 2005; Dynan et al., 2004), the present research highlights the relationship between conspicuous consumption and social self-esteem, prominently among a high social class. Specifically, among those who are in a high subjective social class, the negative relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption was strongly found as well as the negative relationship between social self-esteem and social motivation of consumption. Also, the triggers for their conspicuous consumption are specifically relevant to social confidence, as evinced by the moderating role of social self-esteem.

The findings support that people with high subjective social class identification try to compensate for low social self-esteem by engaging in conspicuous consumption. On the other hand, trait materialism was not influenced by the interaction between social self-esteem and subjective social class. This suggests that individuals in a high social class become conducive to conspicuous consumption when their social self-esteem is low not because their intrinsic interests in material possessions change, but because they strategically adopt conspicuous consumption as a self-presentational means to maintain their social image and standing in the eyes of others.

6.2.2. Social self-esteem as a specific self-esteem

Due to the relevance of social self-esteem to conspicuous consumption, we examine how the role of social self-esteem in the relationship between subjective social status and conspicuous consumption. Although specific self-esteem measures for diverse domains are differentiated from global self-esteem (McCain et al., 2015), not much previous research has employed domain-specific self-esteem measures (Fernandez and Pritchard, 2012). Although the additional analysis reveals that regardless of whether a global self-esteem scale or self-esteem subscales are used, the pattern of the results is similar, the social self-esteem subscale best explains the proposed relationships. This suggests that dampening self-esteem regarding one's social competence seems to drive conspicuous consumption among high social class individuals. As social self-esteem fluctuates more easily than global self-esteem by social stimuli (Thornton and Moore, 1993), changes in social self-esteem translate into conspicuous consumption most closely. Additionally, trait materialism was not influenced by the interaction of subjective social class and social self-esteem. This is partly because we intend to utilize state social self-esteem, which is dynamic but not chronic in order to capture how high class individuals make use of conspicuous consumption to remedy a momentarily lapse in their social self-esteem.

6.2.3. Role of subjective social class

While the importance of material pursuit is also found among the low social class (Li et al., 2018; Mazzocco et al., 2012), the recent empirical finding reveals that the higher people perceive their social class, the more they want status and material success (Wang et al., 2020). This suggests that those who perceive themselves have a high social standing, as well have a strong desire for wealth and status which is socially valuable resources. This might be related to the subjective social class might partly reflect one's desire or want to maintain or become a high social class. While the traditional social class indicators such as occupation or income still exist, middle-income individuals can purchase luxury products as much as high-income individuals as many people aspire to luxury consumption (S. Lee, 2018b). Many subjective measures of the social class tend to produce similar results to an objective measure of social class (Wang et al., 2020). Moreover, a measure of subjective social class was complementarily used together with objective social status indicators (e.g., income) (Kim and Park, 2015). This might be related to the increasingly blurred boundaries in social classes due to social mobilization and the dynamic construction of social class (Eckhardt and Bardhi, 2020). Overall, the subjective social class perception matters no less than social class classification based on objective indicators (e.g., income). The present finding reveals one of the underlying mechanisms of such a relationship by showing that low social self-esteem is related to conspicuous consumption particularly among individuals who perceive them to be in a high social class. They seem to recover their social weakened confidence by engaging in conspicuous consumption that can signal their status and wealth.

6.2.4. Underlying mechanism: social dominance orientation and life satisfaction

Although conspicuous consumption by definition refers to consumption behavior targeting to signal one's status and wealth (Veblen, 2009), the underlying process of conspicuous consumption among different social classes is not investigated much. Our findings show that the moderating role of subjective social class in the relationship between social self-esteem and conspicuous consumption was mediated by social dominance orientation and life satisfaction. Heightened conspicuous consumption under lower social self-esteem is driven by the increased social dominance orientation and the weakened contribution to life satisfaction among people in a high subjective social class. Among those in a high subjective social class, low social self-esteem is related to high social dominance, which in turn is related to conspicuous consumption. This suggests that among individuals in a high social class, low self-esteem seems to lead them to try to restore positive social self-esteem by legitimizing the dominance of their social class. As a result of the heightened social dominance orientation, conspicuous consumption is increased. This link is consistent with previous findings showing that conservatism is related to consumption signaling a superior social position due to social dominance orientation (Ordabayeva and Fernandes, 2018). Also, while life satisfaction tends to serve as a psychological buffer against stressful and difficult events, the incremental benefits of improving social self-esteem to life satisfaction are weaker among those in a high social class. Hence, individuals in a high social class would seek for conspicuous consumption due to the limited shielding of life satisfaction.

6.3. Limitations and future research directions

Although the present studies provide the initial evidence of the underlying mechanism of the interactive effect of subjective social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption, we relied on the cross-sectional data, which only provided correlational evidence. To probe the causality, the future investigation should be made if the changes in state social self-esteem can lead to increased conspicuous consumption among those with high subjective social class or if the subjective social class perception is experimentally manipulated. Also, the present studies relied on the convenient sampling from the online panels that are relatively young compared to the nationally-representative sample. As a result, the finding might be biased. The current findings should be tested among the general population for generalizability.

Also, we adopted subjective social class to see the compensatory consumption pattern among high class individuals in contrast to low class individuals, consistent with an overwhelmingly majority of previous research studies on social class and consumption that relied on two classes: relatively high and low (e.g., high class versus middle class; upper versus lower class; middle class versus low class) (Belmi et al., 2020; Carey and Markus, 2016; Kraus et al., 2009, 2012; Shavitt et al., 2016). However, as recent research has shown that compared to the high and low social class (Yan et al., 2020), the middle class may have different social motivations and thus make different consumption decisions, which highlight the finer classifications of different social classes beyond dividing into two classes only. Also, it has been increasingly acknowledged that the social class and status is dynamic and thus consumption related to class and status changes in a concert (Eckhardt and Bardhi, 2020). Thus, future research can further study whether middle class individuals compared to high and low class may exhibit different response to self-esteem fluctuations by changing their conspicuous consumption. Additionally, while we did not find the interactive effect of social class and social self-esteem on conspicuous consumption, the role of their chronic self-esteem may be likely more closely related to trait materialism. Future research can address the relationship between chronic self-esteem, social class, and conspicuous consumption as trait materialism to establish if the current pattern is found as persistently if the chronic traits and behavioral tendencies are considered.

Lastly, although we purposely sampled American participants to align with the extant literature on conspicuous consumption based on individuals in developed Western countries, it should be tested whether the current implications are generalizable to consumption of different social classes in other developing countries such as China in which individuals’ social identity or self-perceptions might be distinctively related to conspicuous consumption (Cui et al., 2020; Fastoso et al., 2018; Huang and Wang, 2018).

7. Conclusion

This research investigated the relationship between subjective social class and conspicuous consumption by introducing the moderating role of social self-esteem and further testing the mediating roles of social dominance orientation and life satisfaction. While it has been known that people try to compensate for low self-worth or self-esteem by engaging in conspicuous consumption, individual differences in the consumption tendency in a compensatory manner and the underlying process have not been much investigated. The present findings suggest that particularly among those with high subjective social class, social self-esteem is negatively related to conspicuous consumption. Moreover, we demonstrate the underlying mechanism of these relationships by showing the mediating roles of social dominance orientation as well as life satisfaction.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

G-E. Oh: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by The Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee (UGC/IDS/16/17).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abbasi I.S. Social media addiction in romantic relationships: does user's age influence vulnerability to social media infidelity? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019;139:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L.S., West S.G., Reno R.R. sage; 1991. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Tice D.M., Hutton D.G. Self-presentational motivations and personality differences in self-esteem. J. Pers. 1989;57(3):547–579. [Google Scholar]

- Belmi P., Neale M. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the fairest of them all? Thinking that one is attractive increases the tendency to support inequality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2014;124(2):133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Belmi P., Neale M.A., Reiff D., Ulfe R. The social advantage of miscalibrated individuals: the relationship between social class and overconfidence and its implications for class-based inequality. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020;118(2):254–282. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonchoo P., Thoumrungroje A. A cross-cultural examination of the impact of transformation expectations on impulse buying and conspicuous consumption. J. Int. Consum. Market. 2017;29(3):194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Borráz-León J.I., Rantala M.J. Does the Dark Triad predict self-perceived attractiveness, mate value, and number of sexual partners both in men and women? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2021;168:110341. [Google Scholar]

- Bozorgpour F., Salimi A. State self-esteem, loneliness and life satisfaction. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;69:2004–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G.D., Gathergood J. Consumption changes, not income changes, predict changes in subjective well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2020;11(1):64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bruni L., Stanca L. Income aspirations, television and happiness: evidence from the world values survey. Kyklos. 2006;59(2):209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Carey R.M., Markus H.R. Understanding consumer psychology in working-class contexts. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016;26(4):568–582. [Google Scholar]

- Charles K.K., Hurst E., Roussanov N. Conspicuous consumption and race. Q. J. Econ. 2009;124(2):425–467. [Google Scholar]

- Christen M., Morgan R.M. Keeping up with the Joneses: analyzing the effect of income inequality on consumer borrowing. Quant. Market. Econ. 2005;3(2):145–173. [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Fischer E. When conspicuous consumption becomes inconspicuous: the case of the migrant Hong Kong consumers. J. Consum. Market. 2001;18(6):474–487. [Google Scholar]

- Coppock A. Generalizing from survey experiments conducted on Mechanical Turk: a replication approach. Political Science Research and Methods. 2019;7(3):613–628. [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Zhao T., Smyczek S., Sheng Y., Xu M., Yang X. Dual path effects of self-worth on status consumption: evidence from Chinese consumers. Asia Pac. J. Market. Logist. 2020;32(7):1431–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Desmichel P., Ordabayeva N., Kocher B. What if diamonds did not last forever? Signaling status achievement through ephemeral versus iconic luxury goods. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2020;158:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R.A., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dommer S.L., Swaminathan V., Ahluwalia R. Using differentiated brands to deflect exclusion and protect inclusion: the moderating role of self-esteem on attachment to differentiated brands. J. Consum. Res. 2013;40(4):657–675. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D., Jung S., Ordabayeva N. The psychology of luxury consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2021;39:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D., Rucker D.D., Galinsky A.D. Social class, power, and selfishness: when and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015;108(3):436–449. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynan K.E., Skinner J., Zeldes S.P. Do the rich save more? J. Polit. Econ. 2004;112(2):397–444. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt G.M., Bardhi F. New dynamics of social status and distinction. Market. Theor. 2020;20(1):85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Elphinstone B., Whitehead R. The benefits of being less fixated on self and stuff: nonattachment, reduced insecurity, and reduced materialism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019;149:302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Fastoso F., Bartikowski B., Wang S. The “little emperor” and the luxury brand: how overt and covert narcissism affect brand loyalty and proneness to buy counterfeits. Psychol. Market. 2018;35(7):522–532. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez S., Pritchard M. Relationships between self-esteem, media influence and drive for thinness. Eat. Behav. 2012;13(4):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goor D., Keinan A., Ordabayeva N. Status pivoting. J. Consum. Res. 2020 Advance online publication, ucaa057. [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer T. Facebook and people's state self-esteem: the impact of the number of other users' Facebook friends. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;59:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. Guilford publications; 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T.F., Polivy J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991;60(6):895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Ho A.K., Sidanius J., Kteily N., Sheehy-Skeffington J., Pratto F., Henkel K.E., Foels R., Stewart A.L. The nature of social dominance orientation: theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2015;109(6):1003–1028. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Wang C.L. Conspicuous consumption in emerging market: the case of Chinese migrant workers. J. Bus. Res. 2018;86:366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Islam G., Wills-Herrera E., Hamilton M. Objective and subjective indicators of happiness in Brazil: the mediating role of social class. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009;149(2):267–272. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.149.2.267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J., Turrisi R., Jaccard J. Sage; 2003. Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. [Google Scholar]

- Keech J., Papakroni J., Podoshen J.S. Gender and differences in materialism, power, risk aversion, self-consciousness, and social comparison. J. Int. Consum. Market. 2020;32(2):83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kees J., Berry C., Burton S., Sheehan K. An analysis of data quality: professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon's Mechanical Turk. J. Advert. 2017;46(1):141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-H., Park E.-C. Impact of socioeconomic status and subjective social class on overall and health-related quality of life. BMC Publ. Health. 2015;15(1):783. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2014-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Gal D. From compensatory consumption to adaptive consumption: the role of self-acceptance in resolving self-deficits. J. Consum. Res. 2014;41(2):526–542. [Google Scholar]

- Koo J., Im H. Going up or down? Effects of power deprivation on luxury consumption. J. Retailing Consum. Serv. 2019;51:443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus M.W., Piff P.K., Keltner D. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009;97(6):992–1004. doi: 10.1037/a0016357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus M.W., Piff P.K., Mendoza-Denton R., Rheinschmidt M.L., Keltner D. Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 2012;119(3):546–572. doi: 10.1037/a0028756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M.E., Weaver S.L. The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998;74(3):763–773. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary M.R., Tambor E.S., Terdal S.K., Downs D.L. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995;68(3):518–530. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Can a rude waiter make your food less tasty? Social class differences in thinking style and carryover in consumer judgments. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018;28(3):450–465. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Shrum L. Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: a differential needs explanation. J. Consum. Res. 2012;39(3):530–544. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Ashton M.C., Edmonds M. Is the personality—politics link stronger for older people? J. Res. Pers. 2018;77:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Baumgartner H., Winterich K.P. Did they earn it? Observing unearned luxury consumption decreases brand attitude when observers value fairness. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018;28(3):412–436. [Google Scholar]

- Leone L., Desimoni M., Chirumbolo A. HEXACO, social worldviews and socio-political attitudes: a mediation analysis. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2012;53(8):995–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis N. Experiences of upward social comparison in entertainment contexts: emotions, state self-esteem, and enjoyment. Soc. Sci. J. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lu M., Xia T., Guo Y. Materialism as compensation for self-esteem among lower-class students. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018;131:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Liang S., He Y., Chang Y., Dong X., Zhu D. Showing to friends or strangers? Relationship orientation influences the effect of social exclusion on conspicuous consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2018;17(4):355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon S.P., Smith S.M., Carter-Rogers K. Multidimensional self-esteem and test derogation after negative feedback. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement. 2015;47(1):123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan N., Gregg A.P., Sedikides C. Is self-regard a sociometer or a hierometer? Self-esteem tracks status and inclusion, narcissism tracks status. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019;116(3):444–466. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan N., Gregg A.P., Sedikides C. Where I am and where I want to be: perceptions of and aspirations for status and inclusion differentially predict psychological health. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019;139(1):170–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel N., Rucker D.D., Levav J., Galinsky A.D. The compensatory consumer behavior model: how self-discrepancies drive consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017;27(1):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco P.J., Rucker D.D., Galinsky A.D., Anderson E.T. Direct and vicarious conspicuous consumption: identification with low-status groups increases the desire for high-status goods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012;22(4):520–528. [Google Scholar]

- McCain J.L., Jonason P.K., Foster J.D., Campbell W.K. The bifactor structure and the “dark nomological network” of the State Self-Esteem Scale. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015;72:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Meule A. Contemporary understanding of mediation testing. Meta-Psychology. 2019;3:2870. MP. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neave L., Tzemou E., Fastoso F. Seeking attention versus seeking approval: how conspicuous consumption differs between grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. Psychol. Market. 2020;37(3):418–427. [Google Scholar]

- O'cass A., McEwen H. Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. J. Consum. Behav.: Int. Res. Rev. 2004;4(1):25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Oldmeadow J., Fiske S.T. System-justifying ideologies moderate status= competence stereotypes: roles for belief in a just world and social dominance orientation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007;37(6):1135–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Ordabayeva N., Fernandes D. Better or different? How political ideology shapes preferences for differentiation in the social hierarchy. J. Consum. Res. 2018;45(2):227–250. [Google Scholar]

- Palan S., Schitter C. Prolific. ac—a subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2018;17:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Palma M.A., Ness M.L., Anderson D.P. Fashionable food: a latent class analysis of social status in food purchases. Appl. Econ. 2017;49(3):238–250. [Google Scholar]

- Panchal S., Gill T. When size does matter: dominance versus prestige based status signaling. J. Bus. Res. 2019;120:539–550. [Google Scholar]

- Peer E., Vosgerau J., Acquisti A. Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Behav. Res. Methods. 2014;46(4):1023–1031. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0434-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit N.C., Sivanathan N. The plastic trap: self-threat drives credit usage and status consumption. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2011;2(2):146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L.T., Martin S.R., Belmi P. Social class transitions: three guiding questions for moving the study of class to a dynamic perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2020;14(9) [Google Scholar]

- Pratto F., Sidanius J., Stallworth L.M., Malle B.F. Social-dominance orientation - a personality variable predicting social and political-attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994;67(4):741–763. [Google Scholar]

- Richins M.L. The material values scale: measuret properties and development of a short form. J. Consum. Res. 2004;31(1):209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M., Schooler C., Schoenbach C., Rosenberg F. Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: different concepts, different outcomes. Am. Socio. Rev. 1995:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M., Hewstone M. Social identity theory's self-esteem hypothesis: a review and some suggestions for clarification. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1998;2(1):40–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker D.D., Galinsky A.D. Desire to acquire: powerlessness and compensatory consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2008;35(2):257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfan L.D., Clerkin E.M., Teachman B.A., Smith A.R. Do thoughts about dieting matter? Testing the relationship between thoughts about dieting, body shape concerns, and state self-esteem. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatr. 2019;62:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal B., Podoshen J.S. An examination of materialism, conspicuous consumption and gender differences. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013;37(2):189–198. [Google Scholar]

- Shavitt S., Jiang D., Cho H. Stratification and segmentation: social class in consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016;26(4):583–593. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla P. Conspicuous consumption among middle age consumers: psychological and brand antecedents. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008;17(1):25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius J., Levin S., Liu J., Pratto F. Social dominance orientation, anti-egalitarianism and the political psychology of gender: an extension and cross-cultural replication. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000;30(1):41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sivanathan N., Pettit N.C. Protecting the self through consumption: status goods as affirmational commodities. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010;46(3):564–570. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens N.M., Fryberg S.A., Markus H.R., Johnson C.S., Covarrubias R. Unseen disadvantage: how American universities' focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102(6):1178–1197. doi: 10.1037/a0027143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundie J.M., Kenrick D.T., Griskevicius V., Tybur J.M., Vohs K.D., Beal D.J. Peacocks, porsches, and thorstein veblen: conspicuous consumption as a sexual signaling system. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011;100(4):664–680. doi: 10.1037/a0021669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.G., Strutton D. Does Facebook usage lead to conspicuous consumption? J. Res. Indian Med. 2016;10(3):231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton B., Moore S. Physical attractiveness contrast effect: implications for self-esteem and evaluations of the social self. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1993;19(4):474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Uziel L., Cohen B. Self-deception and discrepancies in self-evaluation. J. Res. Pers. 2020;88:104008. [Google Scholar]

- Valeri L., VanderWeele T.J. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure–mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol. Methods. 2013;18(2):137–150. doi: 10.1037/a0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Salfate S., Paez D., Liu J.H., Pratto F., Gil de Zúñiga H. A comparison of social dominance theory and system justification: the role of social status in 19 nations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2018;44(7):1060–1076. doi: 10.1177/0146167218757455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veblen T. Oxford University Press; 2009. The Theory of the Leisure Class. [Google Scholar]

- Walters G.D. Predicting short-and long-term desistance from crime with the NEO personality inventory-short form: domain scores and interactions in high risk delinquent youth. J. Res. Pers. 2018;75:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Griskevicius V. Conspicuous consumption, relationships, and rivals: women's luxury products as signals to other women. J. Consum. Res. 2013;40(5):834–854. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jetten J., Steffens N.K. The more you have, the more you want? Higher social class predicts a greater desire for wealth and status. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020;50(2):360–375. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann R. Conspicuous consumption and satisfaction. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012;33(1):183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B., Struzynska–Kujalowicz A. Power influences self–esteem. Soc. Cognit. 2007;25(4):472–494. [Google Scholar]

- Wood M.J., Gray D. Right-wing authoritarianism as a predictor of pro-establishment versus anti-establishment conspiracy theories. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019;138:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. An examination of the effects of consumption expenditures on life satisfaction in Australia. J. Happiness Stud. 2020;21:2735–2771. [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Jia F. A new procedure to test mediation with missing data through nonparametric bootstrapping and multiple imputation. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2013;48(5):663–691. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2013.816235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Keh H.T., Chen J. Journal of Consumer Research, Ucaa041. Advance online publication; 2020. Assimilating and differentiating: the curvilinear effect of social class on green consumption. [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Sapp S. Motivations of luxury clothing consumption in the US vs. China. J. Int. Consum. Market. 2019;31(2):115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Blader S.L. Why does social class affect subjective well-being? the role of status and power. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020;46(3):331–348. doi: 10.1177/0146167219853841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X., Baskin E., Peng S. Feeling inferior, showing off: the effect of nonmaterial social comparisons on conspicuous consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2018;90:196–205. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.