Abstract

Introduction

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of notifiable infectious diseases (NIDs) in Taiwan remains unclear.

Materials and methods

The number of cases of NID (n = 42) between January and September 2019 and 2020 were obtained from the open database from Taiwan Centers for Disease Control.

Results

The number of NID cases was 21,895 between January and September 2020, which was lower than the number of cases during the same period in 2019 (n = 24,469), with a decline in incidence from 102.9 to 91.7 per 100,000 people in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Fourteen airborne/droplet, 11 fecal-oral, seven vector-borne, and four direct-contact transmitted NID had an overall reduction of 2700 (−28.1%), 156 (−23.0%), 557 (−54.8%), and 73 (−45.9%) cases, respectively, from 2019 to 2020. Similar trends were observed for the changes in incidence, which were 11.5 (−28.4%), 6.7 (−23.4%), 2.4 (−55.0%), and 0.3 (−46.2%) per 100,000 people for airborne/droplet, fecal-oral, vector-borne, and direct-contact transmitted NID, respectively. In addition, all the 38 imported NID showed a reduction of 632 (−73.5%) cases from 2019 to 2020. In contrast, 4 sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) showed an increase of 903 (+7.2%) cases from 2019 to 2020, which was attributed to the increase in gonorrhea (from 3220 to 5028). The overall incidence of STDs increased from 52.5 to 56.0 per 100,000 people, with a percentage change of +6.7%.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a collateral benefit of COVID-19 prevention measures for various infectious diseases, except STDs, in Taiwan, during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Keywords: Airborne/droplet transmission, COVID-19, Epidemiology, Gonorrhea, Notifiable infectious diseases

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), started spreading in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. As of October 30, 2020, COVID-19 has affected over 44 million individuals and caused over 1.1 million deaths [1,2]. In addition to the different clinical manifestations between SARS and SARS-CoV-2 infection [3], the rapid global increase in COVID-19 cases has also put a huge burden on healthcare services. The overwhelming need for COVID-19 patient management has also led to the rapid exhaustion of local response resources and a massive disruption to the delivery of care in many countries. In England, Rashid et al. reported a significant increase in the incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests during the COVID-19 period, paralleled with reduced access to guidelines and recommended care, and increased in-hospital mortality, evaluated using a national cohort of hospitalized acute myocardial infarction patients [4]. Regarding stroke, access to acute stroke diagnostics and time-dependent therapies was limited or delayed owing to reduced emergency service capacities, and a marked reduction in the number of patients admitted with transient ischemic attack and/or stroke was noted in the emergency departments of three European countries (Italy, France, and Germany) [5]. Another study in the United Kingdom showed similar findings, whereby substantial reductions in the activities of patients with cardiac, cerebrovascular, and other vascular complications started 1–2 weeks before the lockdown and dropped to 31–88% following the lockdown [6]. All of these may be attributed to a major burden of the collateral effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast, the global effort to combat COVID-19, particularly the strict implementation of public health control measures, provides some collateral benefit of reducing the spread of other infectious diseases [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. In Japan, cases of seasonal influenza were lower in 2020 than in previous years, which could be associated with the seasonal temperature (local climate), viral virulence, and measures taken to constrain the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak [17]. In a university hospital in Beijing, it was observed that a lower proportion of patients with NID visited pediatric outpatient clinics, especially those with influenza, during the COVID-19 outbreak than in 2019 [18]. In Jiangsu Province, China, the diagnosis of tuberculosis dropped by 52% in 2020 compared to the 2015–2019 period; however, treatment completion and screening for drug resistance also decreased continuously in 2020 [19]. In San Francisco, lower rates of both tuberculosis evaluation and diagnosis were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the same period in 2018 and 2019 [20]. In addition to respiratory infectious diseases, a decrease in the number of sexually transmitted diseases and food-borne infections during the COVID-19 pandemic was noted in Spain [21]. However, these studies [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]] were all conducted in countries with a high burden of COVID-19. We speculated whether a similar scenario would be demonstrated in a country with a well-controlled COVID-19 outbreak, such as in Taiwan.

2. Methods

2.1. The epidemic and control of COVID-19 in taiwan

As of October 28, 2020, there have been 550 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Taiwan, based on the surveillance of 101,021 suspected cases and 220,971 tests [22]. The overall prevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan was 2.31 per 100,000 people. Among them, more than 80% of the cases were classified as imported, and only 55 cases were classified as locally transmitted. Moreover, with only 7 deaths reported, the overall case fatality rate was 1.3% [22]. All these findings indicate that the control of COVID-19 in Taiwan has been highly efficient [23].

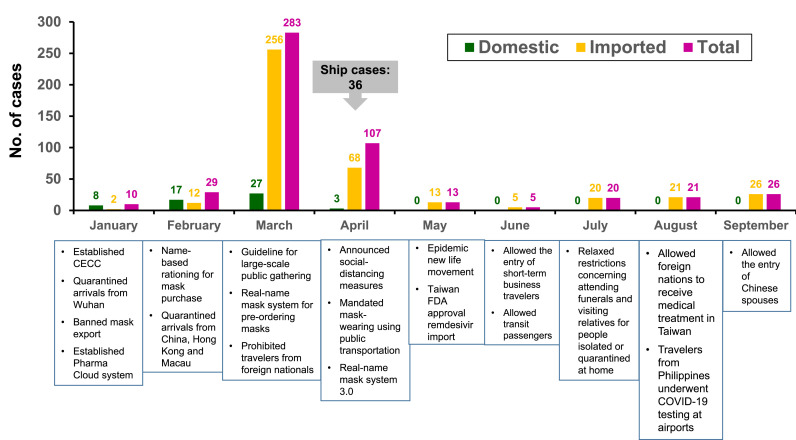

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, Taiwan has implemented various measures for strict infection control and prevention. These measures included wearing a mask, adopting universal hygiene, accurate and comprehensive contact tracing, application of big data, border control, social distancing, avoiding crowded areas, early case-identification using latest technologies, isolating suspected cases, proactive case finding, establishing the Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) to allocate appropriate resources, reassuring and raising awareness among the population, circumventing misinformation through daily press briefings held by the CECC, negotiating with other countries and regions, and formulating policies for schools and childcare by the CECC and the Ministry of Education [[23], [24], [25]]. The epidemic curve of the laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases in Taiwan from January 1 to September 31, 2020 and implementation of infection-control measures are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Epidemic curve of the laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases in Taiwan from January 1 to September 31, 2020 and implementation of infection-control measures. CECC, Central Epidemic Command Center; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

2.2. Sources of data

In Taiwan, a total of 73 infectious diseases have been classified as notifiable infectious diseases (NID) and regular, frequent, and timely information regarding individual cases is considered necessary for the prevention and control of the diseases. Associated data can be collected through the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. Therefore, data obtained in this study was freely available through the open database established by the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (Taiwan CDC) (https://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/nndss/disease?id=025).

2.3. Study period and data analysis

To gain a clear understanding of the potential impact of COVID-19 on NID in Taiwan, the number of the aforementioned cases between January and September in 2019 and 2020 were obtained for comparison. However, we excluded the NID with zero cases in both 2019 and 2020 in this study. Percentage (%) change was defined as the difference in the number of cases (including both indigenous and imported cases) between 2020 and 2019, divided by the number in 2019 and multiplied by 100. During the two periods of evaluation, the population of Taiwan was 23, 816, 775 in 2020 and 23, 773, 876 in 2019. The number of inbound visitors between January and September was 1,315,690 in 2020 and 5,182,834 in 2019, based on the Tourism Statistics Database of the Taiwan Tourism Bureau (https://stat.taiwan.net.tw/inboundSearch). The incidence of NID was defined as the number of cases within those nine months (January–September) per 100,000 people in 2019 and 2020. In addition, the government-funded seasonal influenza vaccination campaign starts since early October annually in Taiwan. The annual report on influenza vaccination coverage rates was available from the Taiwan CDC's database (https://www.cdc.gov.tw/Category/MPage/JNTC9qza3F_rgt9sRHqV2Q).

2.4. Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation of the number of cases were reported as continuous variables, and differences in the numbers were evaluated using the Student's t-test. SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses. Significance was set at a p-value < 0.05 (two-tailed test).

3. Results

Overall, 42 NID were included in this study. The number of cases was 21,895 in 2020 (January–September), which was lower than the number of cases recorded in 2019 (n = 24,469). Thus, the percent change in the total number of cases between 2020 and 2019 was −10.5% (n = 2574). In addition, the incidence of these 42 diseases was 91.7 and 102.9 per 100,000 people in 2020 and 2019, respectively, with a −10.9% change. Among these diseases, 30 NID had fewer cases in 2020 than in 2019. In contrast, 10 NID had a higher number of cases in 2020 than in 2019, whereas two diseases had the same number of cases in both 2019 and 2020.

3.1. Airborne/droplet transmitted diseases

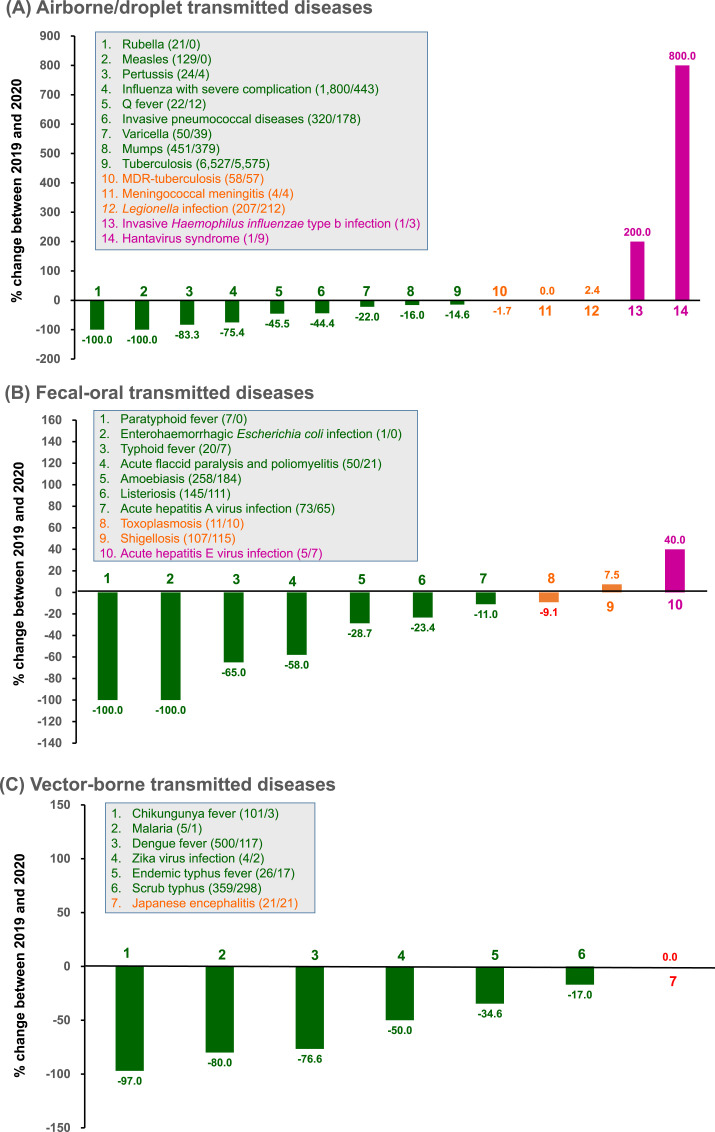

Among the 14 airborne/droplet transmitted diseases, there were fewer cases of ten diseases, including influenza with severe complications (severe influenza), tuberculosis (TB), invasive pneumococcal disease, measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, varicella (-, and multidrug-resistant TB in 2020 than in 2019 (Fig. 2 A). Considering these 14 airborne/droplet transmitted diseases together, there was an overall reduction of 2700 (−28.1%) cases from 2019 to 2020. Their incidence decreased from 40.4 to 29.0 per 100,000 people, with a percentage decrease of −28.4%.

Fig. 2.

Change in the number of cases and rates of (A) airborne/droplet, (B) fecal-oral transmitted, (C) vector-borne, (D) direct-contact transmitted, and (E) sexually-transmitted notifiable infectious diseases between January and September, in 2019 and 2020. Data were retrieved from Taiwan Centers for Disease Control (https://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/nndss/disease?id=025). In the boxes, green indicates changes causing a decline in rates by ≥ 10%, orange indicates the changes in rates within 10%, and purple indicates an increase in rates by ≥ 10%. Numbers in parenthesis denote the number of cases during January–September 2019/January–September 2020. MDR, multidrug-resistant. AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2. Fecal-oral transmitted diseases

Among the 11 fecal-oral transmitted diseases, a decrease in the number of cases was observed in 8 diseases in 2020 than in 2019; these 8 diseases included amoebiasis, listeriosis, acute flaccid paralysis and poliomyelitis, typhoid fever, acute hepatitis A viral infection, paratyphoid fever, and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection (Fig. 2B). Considering these 11 fecal-oral transmitted diseases together, there was a reduction of only 156 (−23.0%) cases from 2019 to 2020. Their incidence decreased from 28.5 to 21.8 per 100,000 people, with a percentage change of −23.4%.

3.3. Vector-borne transmitted diseases

Among the seven vector-borne transmitted diseases, there were fewer cases of six diseases in 2020 than in 2019; these 6 diseases included dengue, chikungunya fever, scrub typhus, endemic typhus fever, malaria), and Zika virus infection (Fig. 2C). Taken together, there was a reduction of 557 (−54.8%) cases of these 7 vector-borne transmitted diseases from 2019 to 2020. Their incidence decreased from 4.3 to 1.9 per 100,000 people, with a percentage change of −55.0%.

3.4. Direct-contact transmitted diseases

Among the 4 direct-contact transmitted diseases, the number of cases of 3 diseases, including enterovirus infection with severe complications, leptospirosis, and Hansen's disease (leprosy) were fewer in 2020 than in 2019 (Fig. 2D). In summary, these 4 direct-contact transmitted diseases showed a reduction of 73 (−45.9%) cases from 2019 to 2020. Their incidence decreased from 0.7 to 0.4 per 100,000 people, with a percentage change of −46.2%.

3.5. Sexually transmitted diseases (STD)

Among the 4 STDs, 3 diseases, including syphilis, HIV infection, and AIDS, showed fewer cases in 2020 than in 2019 (Fig. 2E). In contrast, the number of cases of gonorrhea increased from 2019 to 2020. Finally, in summary, these 4 STDs showed an increase of 903 (+7.2%) cases from 2019 to 2020, which was attributed to the increase in gonorrhea cases. The overall incidence increased from 52.5 to 56.0 per 100,000 people, with a percentage change of +6.7%.

3.6. Severe influenza and gonorrhea

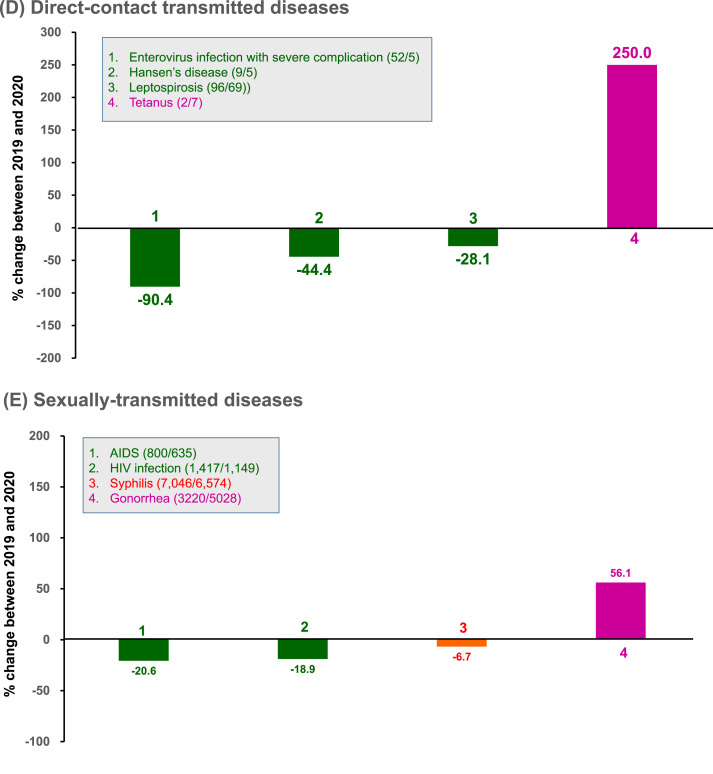

In this study, the number of severe influenza cases was 433 in 2020, which was much lower than that in 2019 (n = 1800). In January, the monthly number was 375 in 2020, which was higher than those in January 2019 (254). However, the monthly number of cases of severe influenza in the other months of 2020 was significantly lower than those in the same period in 2019 (p = 0.033) (Fig. 3 A). In the 2017-18 season, the influenza vaccine coverage for elderly ≥65 years-old, school-aged children/adolescent 7-18 years-old and children 0.5–6 years-old were 45%, 70% and 69%, respectively. In the 2018-19 season, the influenza vaccine coverage for elderly ≥65 years-old, school-aged children/adolescent 7-18 years-old and children 0.5–6 years-old were 51%, 77% and 80%, respectively. Overall, the coverage rate of influenza vaccine in Taiwan was 47% during the 2018–2019 season, which was 5% higher than those in the 2017–2018 season (42%). As for gonorrhea, the monthly number of cases in 2020 was significantly higher than that in 2019 (p = 0.0001) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The number of monthly cases of (A) influenza with severe complication (severe influenza) and (B) gonorrhea reported in Taiwan from January to September of 2019 and 2020.

3.7. Other diseases

Regarding two blood-borne transmitted hepatitis diseases, the number of cases of acute hepatitis B and C viral infections increased from 2019 to 2020.

3.8. Imported NID

A total of 38 NID cases were reported as imported cases. Of these, 16 diseases, including rubella, paratyphoid fever, acute flaccid paralysis and poliomyelitis, measles, acute hepatitis E virus infection, enterovirus infection with severe complications, JE, leptospirosis, endemic typhus fever, Q fever, scrub typhus, varicella, invasive pneumococcal disease, toxoplasmosis, listeriosis, and chikungunya fever, the number of cases was reduced to zero in 2020 (Table 1 ). In addition, the number of cases of cholera, meningococcal meningitis, enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection, Hantavirus syndrome, pertussis, tetanus, and invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b infection remained zero in both 2019 and 2020 (Table 1). In contrast, an increase in the number of acute hepatitis C viral infection cases was observed in 2020 in comparison with 2019. In summary, these 38 imported infectious diseases showed a reduction of 632 (−73.5%) cases from 2019 to 2020.

Table 1.

Epidemiology of imported notifiable infectious diseases (NID) between January and September of 2019 and 2020.

| NID | No. of cases |

Change in no. of cases | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | |||

| Airborne/droplet transmitted diseases | ||||

| Rubella | 17 | 0 | −17 | −100.0 |

| Measles | 51 | 0 | −51 | −100.0 |

| Q fever | 5 | 0 | −5 | −100.0 |

| Invasive pneumococcal disease | 2 | 0 | −2 | −100.0 |

| Varicella | 1 | 0 | −1 | −100.0 |

| Legionella infection | 14 | 7 | −7 | −50.0 |

| Influenza with severe complication | 8 | 4 | −4 | −50.0 |

| Mumps | 8 | 5 | −3 | −37.5 |

| Meningococcal meningitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hantavirus syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Pertussis | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Fecal-oral transmitted diseases | ||||

| Paratyphoid fever | 6 | 0 | −6 | −100.0 |

| Acute flaccid paralysis and poliomyelitis | 1 | 0 | −1 | −100.0 |

| Acute hepatitis E | 4 | 0 | −4 | −100.0 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 2 | 0 | −2 | −100.0 |

| Listeriosis | 1 | 0 | −1 | −100.0 |

| Typhoid fever | 16 | 3 | −13 | −81.3 |

| Acute hepatitis A | 20 | 8 | −12 | −60.0 |

| Shigellosis | 38 | 21 | −17 | −44.7 |

| Amoebiasis | 144 | 103 | −41 | −28.5 |

| Cholera | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Enterohemorrhagic E. coli infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Direct-contact transmitted diseases | ||||

| Enterovirus infection with severe complication | 1 | 0 | −1 | −100.0 |

| Leptospirosis | 1 | 0 | −1 | −100.0 |

| Leprosy | 3 | 2 | −1 | −33.3 |

| Tetanus | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Vector-borne diseases | ||||

| Japanese encephalitis | 2 | 0 | −2 | −100.0 |

| Endemic typhus fever | 3 | 0 | −3 | −100.0 |

| Scrub typhus | 4 | 0 | −4 | −100.0 |

| Chikungunya fever | 80 | 3 | −77 | −96.3 |

| Dengue fever | 408 | 59 | −349 | −85.5 |

| Malaria | 5 | 1 | −4 | −80.0 |

| Zika virus infection | 4 | 2 | −2 | −50.0 |

| Sexually-transmitted diseases | ||||

| Gonorrhea | 2 | 1 | −1 | −50.0 |

| Syphilis | 4 | 3 | −1 | −25.0 |

| Others | ||||

| Acute hepatitis B virus infection | 3 | 2 | −1 | −33.3 |

| Acute hepatitis C virus infection | 2 | 4 | 2 | 100.0 |

4. Discussion

This study investigated the change in the epidemiology of infectious disease before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan, and resulted in several significant findings. The number of cases of >70% of 42 infectious diseases had declined in 2020, as compared to 2019. Overall, in Taiwan, the difference in the number of cases of NID between 2019 and 2020 was 2,574, with a percentage change of −10.5%. One possible explanation could be the aggressive and strict COVID-19 prevention measures implemented in Taiwan since early 2020. Therefore, several infection-control interventions for COVID-19 also had a preventive effect on other infectious diseases, bringing about a collateral benefit–decline of NID. In this study, we also observed the increasing coverage of influenza vaccine from the 2017–2018 season to 208–2019 season, which could also have contributed to the lower case number of influenza during the COVID-19 epidemic. Further long-term and detailed investigations are warranted to validate our findings.

COVID-19 is a respiratory infectious disease and the primary transmission route is through person-to-person contact or through direct contact with respiratory droplets generated when an infected person coughs or sneezes [2]. Therefore, many community mitigation measures, such as wearing a mask, universal hygiene, social distancing, and avoiding crowded areas have been developed to prevent its transmission. These interventions may have caused a decrease in the number of airborne/droplet transmitted diseases from 2019 to 2020, with a reduction of 2700 cases and a percentage change of −28.1%, which was observed in this study. This is consistent with other reports [17,20,[26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]], which revealed decreased influenza activity, Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, streptococcal pharyngitis, respiratory syncytial virus infection, measles, and TB in other countries. These findings support the rationale that COVID-19 prevention measures may have a similar effect in preventing other airborne/droplet transmitted diseases.

In addition to airborne/droplet transmitted diseases, a decrease in fecal-oral, vector-borne, and direct-contact transmitted diseases was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. This decrease was attributed to universal hygiene, social distancing, avoiding crowded areas, being quarantined, and reducing outdoor activities [21]. In contrast, an increase in STDs, particularly gonorrhea (nearly all indigenous cases), was observed in this study. An increase in gonorrhea has also been shown in previous reports [34,35]. In Finland, national lockdown began on March 16 but the restrictions were loosened in early June. The number of gonorrhea was higher in July 2020, compared with reference years – 2015 to 2019 (incidence rate ratio: 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1–1.3) [34]. Although this finding seems counterintuitive as one might expect that shelter at home orders may have promoted greater monogamy, a possible cause may be an association between being quarantined and increased sexual activity. However, the trend of an increase in gonorrhea cases was not observed in syphilis and HIV, which was also demonstrated in previous studies [21,36]. Further studies are needed to clarify these discrepancies.

Finally, we observed a decrease in the number of imported infectious diseases in this study. This could be predominantly due to strict measures in border control. Based on previous experience with SARS, standard operating procedures have been implemented at Taiwan's airports, including swift enforcing of fever-screening of the arriving passengers, screening suspected cases by inquiring about their travel history, occupation, contacts, cluster, and conducting health assessments. Since the early COVID-19 outbreak in China, Taiwan had implemented on-board quarantine inspection in direct flights from Wuhan, China, and promoted related prevention measures among other travelers. After February 7, 2020, passengers arriving from China, Hong Kong, and Macao (including those transiting through these areas) were under strict home quarantine for 14 days. Starting from March 19, foreign nationals were prohibited from entering Taiwan, and in response to the pandemic, home quarantine measures were expanded to include arriving passengers from all countries. Subsequently, the transit of airline passengers through Taiwan was suspended from March 24 onwards, to decrease cross-border movement of people and reduce the risk of disease transmission. Through these border control measures, it is possible that the number of imported infectious diseases was largely reduced. Furthermore, this would indirectly reduce the occurrence of imported cases associated with the local transmission of diseases.

Although the findings of this study were significant, there was several limitations. Several confounding factors that could affect the incidence of these infectious diseases were not assessed in this study. These possible factors included changes in weather, effect of vaccination, decreased sensitivity of surveillance, and hesitation to visit the hospital for diagnosis owing to the fear of contracting COVID-19. In addition, we used comparator (baseline) year was 2019 only. It might have been more accurate to compare with a 5-year average incidence for each NID due to the year-to-year fluctuation in relation to these data in Taiwan. However, our findings were consistent with previous studies using recent 5 year for comparison [37,38]. Fang et al. demonstrated a reduction in TB notifications during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to 2015 to 2019 [37]. Lee et al. showed that a total of 4332 patients with gonorrhea were reported during the first 8 months in 2020, which was much higher than the accumulative case number within the same period between 2015 and 2019 [38].

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a collateral benefit of COVID-19 prevention measures for several other NID in Taiwan during the pandemic. This finding inspires us to continue implementing COVID-19 prevention measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2, as well as other infections. Therefore, we recommend the retention of certain population hygiene measures in the future given the impressive inter-year reduction in NID incidence.

Funding source

There is no funding for this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chih-Cheng Lai: Established the objectives and designed the study, Validation, Data curation, Obtained the data, performed the data management, validated the data, and interpreted the results, Writing – original draft, Wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript. Shey-Ying Chen: Validation, Data curation, Obtained the data, performed the data management, validated the data, and interpreted the results. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript. Muh-Yong Yen: Validation, Data curation, Obtained the data, performed the data management, validated the data, and interpreted the results. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript. Ping-Ing Lee: Validation, Data curation, Obtained the data, performed the data management, validated the data, and interpreted the results. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript. Wen-Chien Ko: Validation, Data curation, Obtained the data, performed the data management, validated the data, and interpreted the results. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript. Po-Ren Hsueh: Established the objectives and designed the study, Writing – original draft, Wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to this paper to optimize and adjust the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors have reviewed and accepted the content of the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Who https://covid19.who.int

- 2.Lai C.C., Shih T.P., Ko W.C., Tang H.J., Hsueh P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su Y.J., Lai Y.C. Comparison of clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) as experienced in Taiwan. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101625. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashid M., Gale C.P., Curzen N., Ludman P., De Belder M., Timmis A., et al. Impact of COVID19 pandemic on the incidence and management of out of hospital cardiac arrest in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction in England. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Oct 7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bersano A., Kraemer M., Touzé E., Weber R., Alamowitch S., Sibon I., et al. Stroke care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experience from three large European countries. Eur J Neurol. 2020 Jun 3 doi: 10.1111/ene.14375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ball S., Banerjee A., Berry C., Boyle J., Bray B., Bradlow W., et al. Monitoring indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on services for cardiovascular diseases in the UK. Heart. 2020 Oct 5 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317870. heartjnl-2020-317870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Georgeo M.R., De Georgeo J.M., Egan T.M., Klee K.P., Schwemm M.S., Bye-Kollbaum H., et al. Containing SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals facing finite PPE, limited testing, and physical space variability: navigating resource constrained enhanced traffic control bundling. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Jul 30 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.07.009. S1684-1182(20)30166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diarra I., Muna L., Diarra U. How the Islands of the South Pacific have remained relatively unscathed in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Jul 10 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.06.015. S1684-1182(20)30156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee E., Mohd Esa N.Y., Wee T.M., Soo C.I. Bonuses and pitfalls of a paperless drive-through screening and COVID-19: a field report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 May 26 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.011. S1684-1182(20)30125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kung C.T., Wu K.H., Wang C.C., Lin M.C., Lee C.H., Lien M.H. Effective strategies to prevent in-hospital infection in the emergency department during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 May 19 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.006. S1684-1182(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung Y.T., Yeh C.Y., Shu Y.C., Chuang K.T., Chen C.C., Kao H.Y., et al. Continuous temperature monitoring by a wearable device for early detection of febrile events in the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Taiwan, 2020. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:503–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aluga M.A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Kenya: preparedness, response and transmissibility. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:671–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F.M., Feng M.C., Chen T.C., Hsieh M.H., Kuo S.H., Chang H.L., et al. Big data integration and analytics to prevent a potential hospital outbreak of COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2021;54:129–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang H.T., Chen T.C., Liu T.Y., Chiu C.F., Hsieh W.C., Yang C.J., et al. How to prevent outbreak of a hospital-affiliated dementia day-care facility in the pandemic COVID-19 infection in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:394–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yen M.Y., Schwartz J., King C.C., Lee C.M., Hsueh P.R. Society of taiwan long-term care infection prevention and control. Recommendations for protecting against and mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term care facilities. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang C.J., Chen T.C., Chen Y.H. The preventive strategies of community hospital in the battle of fighting pandemic COVID-19 in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:381–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakamoto H., Ishikane M., Ueda P. Seasonal influenza activity during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Japan. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1969–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo Z., Li S., Li N., Li Y., Zhang Y., Cao Z., et al. Assessment of pediatric outpatient visits for NID in a university hospital in Beijing during COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q., Lu P., Shen Y., Li C., Wang J., Zhu L., et al. Collateral impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on tuberculosis control in Jiangsu Province, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug 28:ciaa1289. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louie J.K., Reid M., Stella J., Agraz-Lara R., Graves S., Chen L., et al. A decrease in tuberculosis evaluations and diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2020;24:860–862. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Miguel Buckley R., Trigo E., de la Calle-Prieto F., Arsuaga M., Díaz-Menéndez M. Social distancing to combat COVID-19 led to a marked decrease in food-borne infections and sexually transmitted diseases in Spain. J Trav Med. 2020 Aug 25 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa134. taaa134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taiwan Cdc https://www.cdc.gov.tw/En

- 23.Lai C.C., Yen M.Y., Lee P.Y., Hsueh P.R. How to keep COVID-19 at bay: a Taiwanese perspective. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020 Nov 4 doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.201028.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng H.Y., Jian S.W., Liu D.P., Ng T.C., Huang W.T., Lin H.H. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1156–1163. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su Y.F., Yen Y.F., Yang K.Y., Su W.J., Chou K.T., Chen Y.M., et al. Masks and medical care: two keys to Taiwan's success in preventing COVID-19 spread. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101780. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsen S.J., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Budd A.P., Brammer L., Sullivan S., Pineda R.F., et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1305–1309. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marriott D., Beresford R., Mirdad F., Stark D., Glanville A., Chapman S., et al. Concomitant marked decline in prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses among symptomatic patients following public health interventions in Australia: data from St Vincent's Hospital and associated screening clinics, Sydney, NSW. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Aug 25 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1256. ciaa1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soo R.J.J., Chiew C.J., Ma S., Pung R., Lee V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1933–1935. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chow A., Hein A.A., Kyaw W.M. Unintended consequence: influenza plunges with public health response to COVID-19 in Singapore. J Infect. 2020;81:e68–e69. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai C.C., Chen S.Y., Yen M.Y., Lee P.I., Ko W.C., Hsueh P.R. The impact of COVID-19 preventative measures on airborne/droplet-transmitted infectious diseases in Taiwan. J Infect. 2020 Nov 26 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.11.029. S0163-4453(20)30724-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Young G., Peng X., Rebeza A., Bermejo S., De C., Sharma L., et al. Rapid decline of seasonal influenza during the outbreak of COVID-19. ERJ Open Res. 2020 Aug 17;6(3) doi: 10.1183/23120541.00296-2020. 00296-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of Health LaW Diseases NIoI. Infect Dis Wkly Rep Jpn. 2020;22 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rana M.S., Usman M., Alam M.M., Ikram A., Zaidi S.S.Z., Salman M., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Measles surveillance in Pakistan. J Infect. 2020 Oct 8 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.10.008. S0163-4453(20)30650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuitunen I., Ponkilainen V. COVID-19-related nationwide lockdown did not reduce the reported diagnoses of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Finland. Sex Transm Infect. 2021 Jan 4 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054881. sextrans-2020-054881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balestri R., Magnano M., Rizzoli L., Infusino S.D., Urbani F., Rech G. STIs and the COVID-19 pandemic: the lockdown does not stop sexual infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jul 11 doi: 10.1111/jdv.16808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latini A., Magri F., Donà M.G., Giuliani M., Cristaudo A., Zaccarelli M. Is COVID-19 affecting the epidemiology of STIs? The experience of syphilis in Rome. Sex Transm Infect. 2020 Jul 27 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054543. sextrans-2020-054543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang J.L., Chao C.M., Tang H.J. The impact of COVID-19 on the diagnosis of TB in Taiwan. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2020;24:1321–1322. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee K.K., Lai C.C., Chao C.M., Tang H.J. Increase in sexually transmitted infection during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Oct 20 doi: 10.1111/jdv.17005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]