Summary

Black tea is the most widely consumed tea drink in the world and has consistently been reported to possess anti-aging benefits. However, whether theaflavins, one type of the characteristic phytochemicals in black tea extracts, are involved in regulating aging and lifespan in consumers remains largely unknown. In this study, we show that theaflavins play a beneficial role in preventing age-onset intestinal leakage and dysbiosis, thus delaying aging in Drosophila. Mechanistically, theaflavins regulate the condensate assembly of Imd to negatively govern the overactivation of Imd signals in fruit fly intestines. In addition, theaflavins prevent DSS-induced colitis in mice, suggesting theaflavins play a role in modulating intestinal integrity. Overall, our study reveals a molecular mechanism by which theaflavins regulate gut homeostasis likely through controlling Imd coalescence.

Subject areas: Animal Physiology, Molecular Biology, Immunology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Theaflavins extend Drosophila lifespan and increase climbing ability

-

•

Theaflavins prevent age-onset microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal leakage

-

•

Theaflavins downregulate Imd signals maybe through controlling Imd condensation

-

•

Theaflavins alleviate DSS-induced colitis in CD-1 mice

Animal Physiology; Molecular Biology; Immunology

Introduction

Aging, characterized by a decline in physiological functions in individual organ systems and a growing risk of disease and death, involves the accumulation of damage to molecules, cells, and tissues (Alavez et al., 2011; Bartke et al., 2019; Enge et al., 2017). The identification of functional materials or chemicals preventing biological deterioration to delay the aging process and prolong lifespan is undoubtedly pivotal (Barardo et al., 2017; Kapahi et al., 2017). Previous studies have reported that black tea, the most widely consumed tea in the world, possesses significant activities that delay aging (Cameron et al., 2008; Fei et al., 2017; Kumar and Rizvi, 2017; Naumovski et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2020). Dietary supplementation with the extracts of black tea efficiently extends the lifespan of experimental animals such as worms (Fei et al., 2017), fruit flies (Peng et al., 2009; Si et al., 2011), mice (Si et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2020), and rats (Kumar and Rizvi, 2017).

It is well known that black tea extracts mainly contain two kinds of phytochemicals, namely, catechins and theaflavins (TFs) (Cameron et al., 2008; Kondo et al., 2019; Li et al., 2013), the latter of which are produced from catechins by endogenous polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase during the oxidation process in black tea production (Li et al., 2013). A series of studies have identified the antiaging role of the catechins via improving oxidative stresses and age-associated inflammation and reducing tissue damage (Cameron et al., 2008; Niu et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2009; Si et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2015). However, functional studies on the contributions of TFs to aging have greatly lagged behind those on catechins, because it is difficult to extract sufficient amounts of TFs from black tea leaves for medical studies (Takemoto and Takemoto, 2018). Recently, several biosynthetic methods have been developed for the mass production of TFs (Takemoto and Takemoto, 2018), making it possible to explore the exact biological effects of TFs and the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

Recently, increasing sets of data have highlighted the pivotal roles of the intestines in aging and lifespan modulation (Guo et al., 2014; Ji et al., 2019; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018; Rothenberg and Zhang, 2019; Salazar et al., 2018). The intestinal epithelium, which acts as a selective barrier, allows the absorption of nutrients, ions, and water and limits host contact with harmful entities, including microorganisms, dietary antigens, and environmental toxins (Capo et al., 2019; Nicholson et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2010). As a high-turnover tissue in individuals, the intestinal tract provides the best living environment for symbiotic microorganisms, including natural anaerobic conditions, abundant nutrients, and a suitable temperature and pH value, forming niches occupied by specific bacterial species in the body (Bonfini et al., 2016; Buchon et al., 2013; Nicholson et al., 2012). Meanwhile, these symbiotic microorganisms and their metabolites also directly or indirectly affect nutrient processing; digestion and absorption; energy balance; immune function; gastrointestinal development and maturation; and many other important physiological activities (Bonfini et al., 2016; Broderick, 2016; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018; Nicholson et al., 2012). The mutually beneficial relationship between the two symbionts can maintain the stability and dynamic balance of the intestinal microecosystem (Bonfini et al., 2016; Broderick, 2016; Broderick et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2014; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018; Nicholson et al., 2012).

A series of studies have shown that the innate immune response is critical for maintaining intestinal microbiota homeostasis and is conserved from invertebrates to vertebrates (Guillou et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2014; Ryu et al., 2006, 2010; Vijay-Kumar et al., 2010). In Drosophila, two major signaling pathways, namely, the Toll and immune deficiency (Imd) pathways, are involved in the innate immune responses (Lu et al., 2020; Myllymaki et al., 2014; Valanne et al., 2011). Notably, the Drosophila Toll pathway shares similarities with the mammalian interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) and MyD88-dependent Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways, whereas the Imd pathway is similar to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) pathway and the TRIF-dependent TLR pathway in mammals (Imler, 2014; Myllymaki et al., 2014; Valanne et al., 2011). These two pathways control the expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) through activation of NF-κB transcription factors (Imler, 2014; Myllymaki et al., 2014; Valanne et al., 2011). The Imd signaling pathway is normally activated by Gram-negative bacterial infection and results in the expression of another set of AMPs, such as Attacin, Cecropin, and Diptericin (Kleino and Silverman, 2014; Myllymaki et al., 2014). Expression of these AMPs requires the peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP)-LC receptor in the Imd pathway and the signal-dependent cleavage and nuclear translocation of Relish, an NF-κB family transcription factor (Kleino and Silverman, 2014; Myllymaki et al., 2014). A recent study showed that amyloid formation is required for activation of the Drosophila Imd pathway upon recognition of bacterial peptidoglycans (Kleino et al., 2017). However, whether this Imd condensate is involved in other biological processes, such as intestinal homeostasis maintenance and aging regulation, remains largely unknown.

In the present study, we utilized fruit flies and mice as animal models to investigate the roles of TFs in controlling intestinal integrity and aging. We showed that TFs delay the age-onset overproliferation of intestinal stem cells, protect against dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, and prevent activation of the Imd signaling pathway, thus prolonging lifespan in Drosophila. Further mechanistic studies indicated that TFs negatively contribute to Imd signaling maybe through blocking condensation of Imd rather than its ubiquitination. Moreover, we found that TFs are highly effective in preventing DSS-induced colitis in mice. Taken together, our findings reveal a potential role of TFs in modulating Imd behavior, which could be the key factor in their positive contributions to intestinal homeostasis and lifespan extension.

Results

Dietary supplementation of theaflavins extends Drosophila lifespan

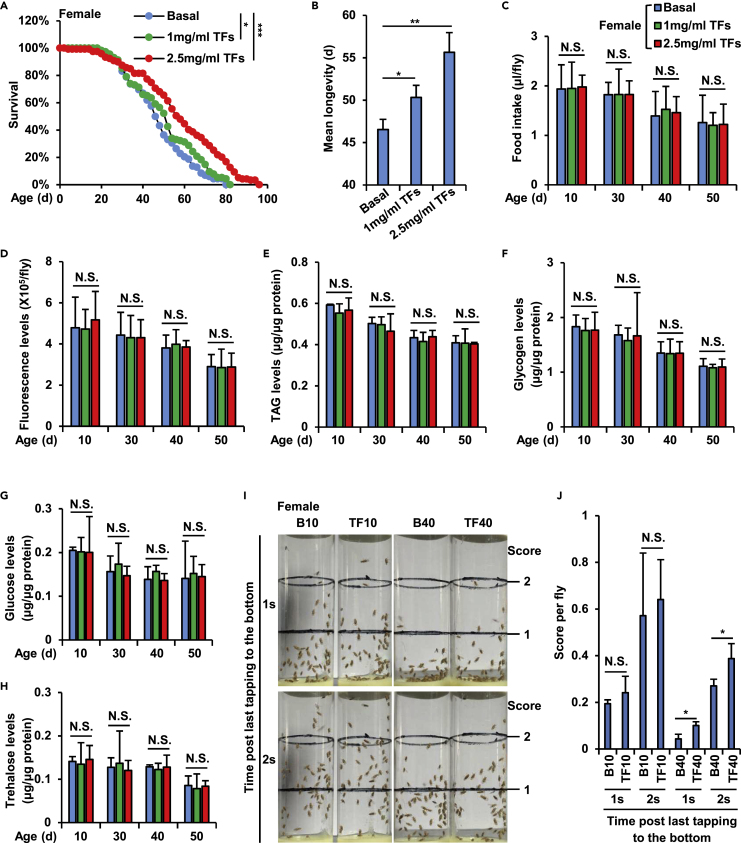

To examine whether theaflavins (TFs) affect aging and lifespan in Drosophila, we raised female w1118 flies with standard rearing foods that were supplemented with 1 mg/mL or 2.5 mg/ml TFs and performed lifespan assays as previously described (Ji et al., 2019). Flies fed a diet supplemented with an equal volume of TFs solvent (H2O) were considered as controls. As shown in Figure 1A, dietary addition of a relatively low concentration of TFs (1 mg/mL) slightly prolonged the fruit fly lifespan, and a high concentration of TFs (2.5 mg/mL) had a significantly positive effect on lifespan extension. Notably, long-term uptake of high concentrations of TFs (2.5 mg/mL) resulted in approximately 8 days elevation in the average lifespans of female flies (Figure 1B), suggesting a beneficial role of TFs in regulating longevity in Drosophila. Similar results were obtained when we tested potential effects of additional TFs on lifespan of male w1118 flies (Figures S1A and S1B).

Figure 1.

Theaflavins prolong Drosophila lifespan and enhance climbing ability

(A and B) Female w1118 fruit flies were cultured with standard foods that were supplemented with 1 mg/mL or 2.5 mg/mL theaflavins (TFs) or without TFs as basal. Flies were transferred to fresh vials containing new media every other day, and dead flies were scored throughout the adult lifespan. Survival curves (A) and mean longevity (B) of female flies were analyzed and shown.

(C and D) Female w1118 were fed with standard Drosophila foods (referred as Basal) or with foods supplemented with 1 mg/mL or 2.5 mg/ml TFs, respectively. Six independent groups of flies at the indicated ages (10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively) were subjected to the cafe (C) and the Fluorescein feeding (D) assays.

(E–H) Female w1118 were reared in the same condition as in (C). At indicated ages (10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively), the flies were subjected to metabolic assays. The calculated levels of TAG (E), glycogen (F), glucose (G), and trehalose (H) were presented.

(I and J) RING test showing the climbing ability of the indicated female w1118 flies (I). The scores per fly at the ages of 10 days and 40 days were analyzed and shown in (J).

In A, Log Rank test was used for statistical analysis. In B–H and J, two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis, and data are shown as means ± SEM. In A–H and J, N.S., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S1.

TFs have been known to have a bitter flavor, and bitter foods are usually avoided by both consumers including fruit flies and mammals (Yamazaki et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2018). We then sought to elucidate whether TFs can impact Drosophila food intake, because previous studies have proven that dietary restriction leads to extended lifespan both in vertebrates and invertebrates (Hudry et al., 2019; Kapahi et al., 2017; Moger-Reischer et al., 2020). To do this, we first performed the cafe assay, a widely used approach to directly and accurately measure the feeding rate by making use of a capillary feeder containing a liquid medium, as previously described (Ja et al., 2007). As shown in Figures 1C and S1C, dietary supplementation of TFs (1 mg/mL and 2.5 mg/mL, respectively) hardly altered the food consumption of tested flies. To further confirm this, we then utilized the Fluorescein as a food tracer (Rera et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2005) and performed a natural feeding assay (Danilov et al., 2015). As shown in Figures 1D and S1D, we failed to observe any correlations between TFs supplementation and levels of food intake. Taken together, our results suggested that the beneficial roles of TFs in prolonging lifespan may not be due to dietary restriction in Drosophila.

Additional TFs are dispensable for impacting Drosophila energy homeostasis

It has been suggested that black tea polyphenols exert a positive effect on preventing obesity by inhibiting lipid and saccharide digestion, absorption, and intake, thus reducing calorie intake (Cameron et al., 2008). We then sought to elucidate whether TFs-regulated Drosophila lifespan extension is due to alterations in nutrient absorption and energy storage. To do this, we firstly examined levels of triacylglyceride (TAG), one of the most commonly detected lipid metabolites (Tennessen et al., 2014), in female flies throughout the whole life as previously described (Fan et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 1E, treatment of TFs hardly impacted overall TAG abundances at different age points. When we further detected glycogen contents and quantified circulating carbohydrates (glucose and trehalose) by the Hexokinase kit (Li et al., 2018; Tennessen et al., 2014), the results showed that there were no obvious alterations between samples with or without TFs treatment (Figures 1F–1H). Of note, consistent results were obtained when we examined metabolic phenotypes utilizing male w1118 as animal models (Figures S1E–S1H). Collectively, these data suggested that dietary supplementation of TFs is dispensable for regulation of carbohydrate and energy homeostasis throughout lifespan in Drosophila.

We further investigated the kinetics of the natural senescence of Drosophila under dietary TFs intervention by performing rapid iterative negative geotaxis (RING) tests as previously described (Dilliane et al., 2017; Staats et al., 2018). As shown in Figures 1I, 1J, S1I, and S1J, climbing indexes of aged (40 days) w1118 (both females and males) in TFs supplementation groups were markedly improved (an almost 12% increase in females and nearly 18% elevation in males) compared with control groups, suggesting that TFs potentially improve Drosophila climbing and locomotor activities.

Theaflavins prevent age-onset gut leakage and microbiota dysbiosis

Previous studies have shown that fruit fly locomotor activities and lifespan are highly related to the host health condition, such as sex, diet, age, and genotype (Caruso et al., 2013; Heintz and Mair, 2014). Recently, several lines of evidence have proven that preserving intestinal Imd signaling homeostasis ameliorates gut integrity by prevention of over-proliferation of ISC and precursor cells and by delaying age-onset intestinal epithelial dysfunction, which in turn positively contributes to organismal health (Clark et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2014). In Drosophila, a shortened lifespan is closely associated with dysfunction of the intestinal epithelial barrier, and development of the integrity of this barrier during aging results in lifespan extension (Clark et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2014; Ji et al., 2019). Thus, we sought to determine whether TFs alter the integrity of the intestine by performing the Smurf assay, a method that has been described previously (Clark et al., 2015; Rera et al., 2011). As shown in Figure 2A, the tested fruit flies in which blue dyes were restricted to the digestive tract were referred to as non-Smurf (left panel in Figure 2A). If blue dyes were observed leaking out from the guts into the abdomen, the hosts were counted as Smurf (right panel in Figure 2A). Consistent with previous findings (Clark et al., 2015), the proportions of Smurf gradually increased during aging (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the proportions of Smurf adults were greatly decreased in the TFs-fed groups compared with the age-matched controls in both female (from 8.2% to 3.7%, from 19.4% to 15.6%, and from 35.4% to 27.1% for groups at ages of 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively, Figure 2B) and male adults (from 2.7% to 0.9%, from 6.9% to 0.9%, and from 8.3% to 2.7% at ages of 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively, Figure S2A), indicating that TFs can prevent intestinal barrier dysfunction in aged fruit flies. Of note, we observed larger decreases of Smurf percentages in males (reduced by almost 65.8%, 86.9%, and 67.4% at ages of 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively) than those in age-matched females (reduced by almost 54.1%, 19.5%, and 23.3% at ages of 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively), implying that TFs might play a better role in lowering intestinal leakage in male flies.

Figure 2.

Theaflavins prevent age-onset gut dysfunction and microbiota dysbiosis in Drosophila

(A and B) Loss of intestinal integrity was assayed by the Smurf test at the ages of 10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days of female w1118 adults. Examples of non-Smurf and Smurf were shown in (A). Percentages of Smurf in different indicated groups were analyzed and shown in (B).

(C) Bacterial abundances assayed by qPCR of the 16S rRNA gene in female w1118 files from different indicated groups were analyzed and shown.

(D–F) Sequencing of the commensal bacterial 16S rRNA gene was performed. The proportions of bacterial taxa (D), a heatmap of the main microbial taxa (E) and the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria (F) were analyzed and presented.

(G and H) Guts were dissected from the indicated female flies fed with 2.5 mg/ml TFs or without TFs as control at the 10 days and 40 days of ages. Images of midgut slides were captured by fluorescence microscopy for GFP signals (G). Statistical analysis showing the percentages of GFP-positive cells is shown in (H).

(I) Guts from the indicated female flies were collected and subjected to immunostaining assays utilizing antibodies against phosphorylated Histone 3 (pH3). Statistical results quantifying pH3-positive cells per gut were analyzed and shown. In B, C, H, and I, data are analyzed by the two-tailed Student's t test and are shown as means ± SEM. N.S., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S2.

Previous studies have suggested that age-onset intestinal barrier dysfunction is often correlated with dysbiosis of the gut microbiota (Clark et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2014). Thus, we examined the intestinal commensal bacterial composition after TFs supplementation. We first utilized universal primers and performed quantitative PCR experiments to quantify the bacterial 16S rRNA gene levels. As shown in Figure 2C, in aged guts, the total bacterial population from TFs intervention groups showed a striking reduction (almost 45%–55%) compared with the controls, suggesting that TFs supplementation probably prevents microbiota expansion during aging. Then, we performed metagenomics to examine in detail the alterations in the intestinal microbial community caused by dietary supplementation with TFs. As shown in Figures 2D–2F, the proportion of Gammaproteobacteria, the expansion of which was found to be closely associated with intestinal barrier failure (Clark et al., 2015), was obviously decreased by TFs supplementation in aged intestines (an almost 7% reduction), implying that TFs positively contribute to the homeostasis of the gut microbiota during aging in Drosophila.

Theaflavins improve intestinal proliferative homeostasis in Drosophila

We further examined the intestinal integrity of flies that were treated with or without TFs. First, we employed the widely used P{Esg-Gal4}/P{Uasp-GFP}; {Tub-Gal80ts} strain (referred to as esgts > GFP), in which the intestinal stem cells (ISCs) and progenitor cells were labeled with GFP. As shown in Figures 2G and 2H, the number of GFP-positive cells in the TFs intervention groups at age 40 days (20 guts were counted) was much less (nearly 29.7%) than that in the age-matched controls (almost 47.6% and 19 guts were counted), suggesting that TFs might inhibit the age-onset overproliferation of ISCs. Furthermore, we performed immunostaining experiments utilizing antibodies against Phospho-Histone 3 (pH3), a specific marker for mitotic cells in gut tissues. We observed fewer pH3-positive cells in the guts from aged TFs-supplemented adults (the mean number was 20.6) than in those from the controls (the mean number was 39.5, Figure 2I). Taken together, our results suggest that dietary supplementation with TFs ameliorates intestinal proliferative homeostasis and prevents age-onset microbiota dysplasia, thus delaying aging in Drosophila.

Theaflavins negatively modulate intestinal Imd signals

To explore the underlying molecular mechanisms by which TFs positively contribute to Drosophila gut homeostasis, we performed RNA-seq analysis utilizing age-matched intestinal samples from female w1118 adults treated with or without TFs. Fragments per kilobase per million (FPKM) analyses suggested that the overall gene expression patterns were similar between the two experimental groups (Figure 3A). Further differential expression analysis, however, identified a total of 229 differentially expressed genes, of which 99 were upregulated and 126 were downregulated (Figure 3B). Interestingly, gene ontology analysis of these genes revealed that the immune response pathway was highly altered by dietary supplementation with TFs (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Theaflavins prevent age-onset activation of Imd signals in Drosophila guts

(A–C) Guts were isolated from aged female w1118 flies (40 days) fed 2.5 mg/ml TFs or without TFs (control). Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RNA-seq analysis. FPKM distribution (A), DESeq R package analysis (B), and gene ontology analysis (C) of differentially expressed genes between TFs-treated and control samples were analyzed and shown.

(D) RNA-seq analysis revealed an array of AMP genes that were downregulated by TFs intervention.

(E–G) Guts were isolated from female w1118 files fed with 2.5 mg/ml TFs or without TFs as basal at 10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days of age, respectively. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to qRT-PCR analyses. The mRNA expression levels of diptericin (E), attacin (F), and cecropin A1 (G) were analyzed and shown. In E–G, data are analyzed by the two-tailed Student's t test and shown as means ± SEM. N.S., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S3.

In Drosophila, innate immune signaling pathways have been proven to play a dominant role in regulating age-onset gut homeostasis and longevity (Clark et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2014). We then focused on examining the expression patterns of the antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) downstream of the innate immune signals. As shown in Figure 3D, AMP genes governed by the immune deficiency (Imd) pathway, including diptericin A (DptA), diptericin B (DptB), attacin A (AttA), cecropin A1 (CecA1), cecropin A2 (CecA2), and cecropin C (CecC), were significantly decreased (by 39.4%, 72.3%, 10.5%, 86.5%, 99.8%, and 36.1%, respectively) in TFs-treated groups compared with the control groups. To further confirm the results obtained from RNA-seq analysis, we carried out quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to quantify the relative expression levels of Imd-related AMP genes in Drosophila gut samples obtained at four different age points including 10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days. As shown in Figures 3E–3G, the mRNA expression levels of certain genes, including diptericin, attacin, and cecropin A1, were significantly decreased (by almost 35.9%–66.6%) in TFs-treated aged guts. Collectively, our data revealed that TFs potentially antagonized the activation of the Imd signaling pathway in Drosophila gut cells during aging.

Theaflavins are dispensable for transcriptional regulation of the Imd pathway or ubiquitination of Imd

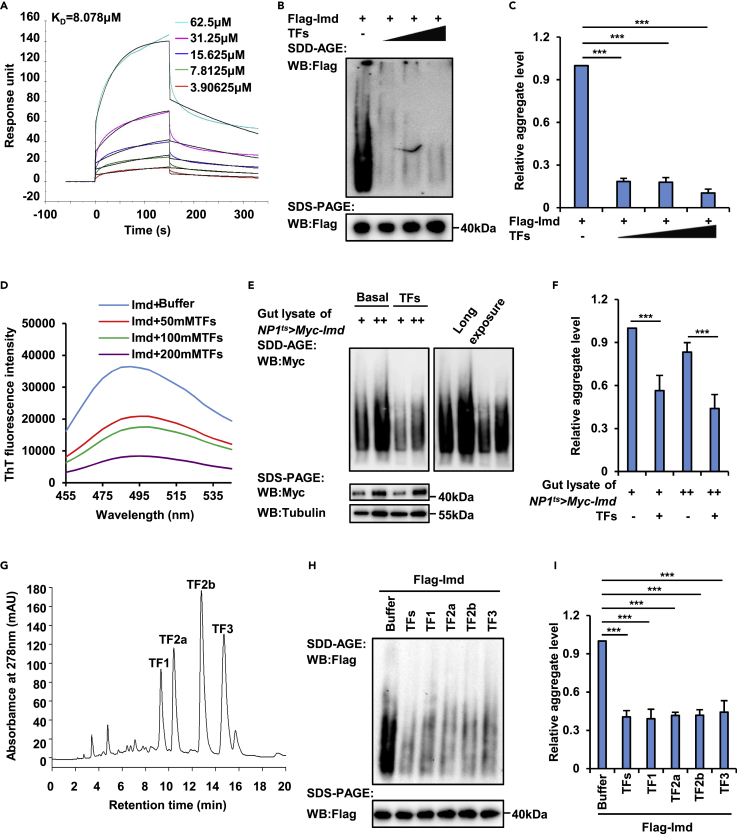

We sought to examine the association between TFs and Imd and performed the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay as previously described (Lan et al., 2020). As show in Figure 4A, TFs exhibited moderate binding affinity with purified Imd protein at an estimated KD constant of 8.078 μM. Then we tend to determine how TFs control the intestinal Imd signaling pathway. Based on the results of transcriptome analysis from RNA-seq data, we found that the expression levels of the key regulatory factors in the Imd signaling pathway, such as PGRP-LC, Imd, and Relish, were hardly altered by TFs treatment (Figure S3A). We further collected gut samples from flies that were subjected to dietary supplementation with or without TFs at various ages and performed qRT-PCR experiments to specifically detect the expression patterns of these genes. As shown in Figure S3B, the mRNA levels of certain genes, including effete, fadd, tak1, pgrp-lca, uev1a, bendless, relish, imd, pgrp-sc2, tab2, ird5, kenny, and diap2, were similar between the control groups and TFs intervention groups, suggesting that TFs are not involved in regulating Imd signals at the transcriptional level.

Figure 4.

Theaflavins inhibit the condensation of Imd

(A) SPR assay determined the binding affinity between TFs and Imd protein using a BIAcoreT200 system. The estimated KD was 8.078 μΜ; ka was 374.6 (1/Ms); kd was 0.003029 (1/s).

(B and C) Purified Flag-Imd proteins were incubated with different concentrations of TFs (50 μM, 100 μM, and 200 μM, respectively) at room temperature for 30 min and were subjected to SDD-AGE (upper panel in B) and SDS-PAGE (lower panel in B) assays to determine the aggregation patterns of Imd. Densitometry analysis to quantify the Imd condensates in different samples was performed and shown in (C).

(D) Purified Imd proteins were incubated with various concentrations of TFs (50 μM, 100 μM, and 200 μM, respectively) at room temperature for 5 min. Samples were then subjected to fluorescence emission spectrum analysis using the indicated wavelengths (excitation at 430 nm, emission from 450 nm to 550 nm with a slit width of 5 nm). A sample without TFs was used as the baseline control.

(E and F) Lysates of guts from NP1ts> Myc-Imd flies were prepared and incubated with TFs (100 μM) at room temperature for 30 min. SDD-AGE (upper panel in E) and SDS-PAGE (lower panel in E) assays were performed to analyze Imd protein aggregates. Tubulin was used as the loading control. Densitometry analysis was performed to quantify Imd condensates in different samples, and the results were shown in (F).

(G) A representative chromatogram of TFs sample.

(H and I) Purified Flag-Imd proteins were incubated with TFs, TF1, TF2a, TF2b, or TF3 (100 μM for each sample) or with an equal volume of buffer (control) at room temperature for 30 min as indicated. Samples were then subjected to SDD-AGE (upper panel in H) and SDS-PAGE (lower panel in H) assays to determine the aggregation patterns of Imd. Densitometry analysis to quantify Imd condensates in different samples was performed and shown in (I). In C, F, and I, data are analyzed by the two-tailed Student's t test and shown as means ± SEM. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S4.

Next, we examined the Imd ubiquitination profiles because previous studies have suggested that ubiquitination of Imd is essential for downstream signal transduction in the Imd pathway (Myllymaki et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2005). We first performed an in vitro E1 shifting assay and found that treatment with TFs has no apparent influence on the enzymatic reactions of E1 and ubiquitin to form conjugated E1/Ub (Figure S4A). Moreover, we transfected Drosophila S2 cells with plasmids expressing Flag-tagged Imd together with HA-tagged Ub and then treated the cells with or without TFs. Further ubiquitination assays suggested that TFs supplementation barely affected the levels of ubiquitinated Imd in cultured cells (Figures S4B and S4C). To determine the relationships between TFs and Imd ubiquitination in vivo, we utilized the transgenic fly P{NP1-Gal4}/P{Uasp-Myc-Imd}; P{Tub-Gal80ts} (referred to as NP1ts > Myc-Imd), in which a Myc-tagged Imd protein was highly expressed in gut cells (Figure S4D). Our ubiquitination experiments showed that dietary supplementation with TFs was dispensable for modulating the ubiquitination of Imd in gut tissues (Figures S4D and S4E). Taken together, our results indicated that TFs negatively govern Drosophila Imd signals by not affecting the ubiquitination pattern of Imd.

Theaflavins prevent Imd condensate assembly

A recent study suggested that aggregation of Imd is essential for activation of downstream genes in the Imd pathway (Kleino et al., 2017). We then sought to examine whether TFs regulate the process of Imd aggregate formation. First, we purified Myc-tagged Imd proteins from cultured S2 cells and incubated the proteins with different concentrations of TFs (Figure 4B). Interestingly, we found that TFs markedly prevented the aggregation of Imd (reduced by 81.7%–89.7%, Figures 4B and 4C), as suggested by our semidenaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) assays. To confirm this finding, we further performed thioflavin-T binding assays and obtained consistent results (Figure 4D). Last, we raised NP1ts > Myc-Imd transgenic flies that were subjected to dietary supplementation with or without TFs and collected gut samples from aged adults. The SDD-AGE experiments suggested that aggregation of Imd was greatly downregulated by TFs in intestinal cells (decreased by 16.7%–22%, Figures 4E and 4F).

To determine how TFs contribute to controlling Imd condensate assembly, we subjected TFs to HPLC analysis and found that they mainly contained four kinds of monomers (Figure 4G), namely, theaflavin (TF1), theaflavin 3-O-gallate (TF2a), theaflavin 3′-O-gallate (TF2b), and theaflavin 3,3′-di-O-gallate (TF3), which were consistent with previous reports (Li et al., 2013; Takemoto and Takemoto, 2018). Then, we incubated each of these chemicals with purified Imd protein and performed SDD-AGE experiments. As shown in Figures 4H and 4I, treatment of all these TF monomers resulted in a marked reduction (by 59.5%, 60.9%, 58.4%, 58.2%, and 55.8% for TFs, TF1, TF2a, TF2b, and TF3, respectively) in the Imd aggregate levels. Collectively, our results suggested that TFs negatively regulate the Drosophila Imd signaling pathway probably by controlling the behavior of Imd condensates.

Theaflavins extend Drosophila lifespan in an Imd-dependent manner

To examine whether TFs prolong Drosophila lifespan depending on their regulatory role in Imd, we specifically knocked down Imd in gut tissues using the transgenic flies P{NP1-gal4};P{Tub-gal80ts}/P{Uasp-imd-IR(KK)} (referred to as Imd RNAi). As shown in Figures 5A and 5B, dietary supplementation of TFs extended lifespan of controls (elevation of nearly 7.2 days in the mean lifespan), whereas prevention of Imd expression in guts apparently reversed the lifespan extension caused by TFs. Consistent results were obtained when we utilized male Imd RNAi and control flies to perform lifespan assays (Figures S5A and S5B). Further qRT-PCR assays showed that the mRNA expression levels of AMP genes at ages of 10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, including diptericin, attacin, and cecropin A1, hardly changed in the gut tissues of Imd RNAi flies (Figures 5C–5E), whereas additional TFs caused reductions of 31%–72.3% in mRNA abundances of these genes in samples from control groups.

Figure 5.

Theaflavins delay Drosophila aging in an Imd-dependent manner

(A and B) Female Imd RNAi (NP1ts > Imd RNAi) and control (NP1ts>+) flies were fed with standard Drosophila foods (referred as Basal) or dietary supplementation with 2.5 mg/mL (referred as TFs), respectively. Flies were then subjected to lifespan assay. Survival curve (A) and mean longevities (B) were analyzed and shown.

(C–E) Guts were collected from indicated female flies at ages of 10 days, 30 days, 40 days, and 50 days, respectively. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to qRT-PCR assays to detect the mRNA expression levels of diptericin (C), attacin (D), and cecropin A1 (E).

(F and G) Female w1118 (referred as imd+/+), imd1 heterozygous and homozygous mutants (referred as imd+/− and imd−/−, respectively) were reared with standard Drosophila foods (referred as Basal) or dietary supplementation with 2.5 mg/mL (referred as TFs) and then were subjected to lifespan assays. Survival curve (F) and mean longevities (G) were analyzed and shown.

In A and F, the Log Rank test was used for statistical analysis. In B–E, and G, the two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis, and data are shown as means ± SEM. N.S., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S5.

To confirm these results from Imd RNAi flies, we first performed lifespan assays using w1118 (control, referred as imd+/+), imd1 heterozygous (referred as imd+/−) and homozygous (referred as imd−/−) mutant flies. We found that TFs addition extended lifespan and increased mean life longevity of imd+/− flies (elevation of nearly 6.2 days, Figures 5F and 5G). However, this lifespan extension effect by TFs was almost abolished in imd−/− flies (Figures 5F and 5G). Next, we performed lifespan assays utilizing Relish RNAi (NP1ts > Relish RNAi) and control (NP1ts>+) flies, because Relish is the key transcription factor responsible for Imd-downstream AMP gene expressions (Myllymaki et al., 2014). As shown in Figures S5C and S5D, dietary addition of TFs markedly prolonged the longevity of control flies, and this extension in lifespan was significantly prevented in Relish RNAi flies. Collectively, our data indicated that dietary supplementation of TFs positively contributes to Drosophila lifespan likely depending on intestinal Imd signals.

In order to see whether the extension of lifespan by TFs still occurs in an axenic background, we performed lifespan assays using w1118 females under axenic condition. As shown in Figures S5E and S5F, addition of different concentrations of TFs (1 mg/mL and 2.5 mg/mL) hardly affected the ratios of mortality and mean life longevity in w1118 adults. Because axenic rearing condition can largely prevent abundant microbiota, thus restricting Imd signals in guts (Clark et al., 2015), our data suggested TFs prolong Drosophila lifespan maybe through modulation of gut microbiota-regulated innate immune signals.

Theaflavins alleviate DSS-induced colitis in CD-1 mice

To further investigate the potential role of TFs in maintaining intestinal homeostasis in mammals, CD-1 mice were used to induce colitis by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS). Mice were intragastrically administered different concentrations of TFs (1 g/L, 2.5 g/L, or 5 g/L) or water as a control for four weeks, followed by treatment with 2% DSS in drinking water for 7 days. In order to see whether TFs affect drinking amount of DSS across different group of mice, we monitored mice drink every day. As shown in Figure 6A, TFs treatment is dispensable for impacting drink consumption in DSS-induced colitis mice. DSS-treated mice presented colitis syndrome with diarrhea and/or hematochezia, which were prevented by dose-dependent TFs treatment (Figures S6A–S6E). Moreover, intervention with TFs rescued the reduction in colon length caused by DSS and ameliorated the enlargement of the spleen (Figures 6B–6D).

Figure 6.

Theaflavins alleviate DSS-induced colitis in CD-1 mice

(A) TFs treatment did not impact water consumption in various groups of CD-1 mice.

(B–D) Gavage administration of various concentrations of TFs (1 mg/mL, 2.5 mg/mL, and 5 mg/mL, respectively) ameliorated the shortening of the colon and enlargement of the spleen caused by DSS in CD-1 mice. Representative images (B) and statistical analyses of the colon (C) and spleen (D) were shown.

(E) Administration of various concentrations of TFs (1 mg/mL, 2.5 mg/mL, and 5 mg/mL, respectively) prevented gut leakage induced by DSS in CD-1 mice.

(F and G) Colons were collected from indicated groups of mice. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to qRT-PCR assays to detect the mRNA expression levels of TNFα (F) and IL-6 (G).

(H–L) Colons from various groups of mice were collected longitudinally and subjected to HE staining assays. Samples were examined by microscopy, and representative images of the indicated samples (H–L) were obtained and shown. Scale bars, 40 μm.

(M–Q′) SEM images showing the microtrichomes of colons from different indicated samples. Scale bars, 50 μm (M–Q) and 4 μm (M′–Q′).

In C–G, data are analyzed by the two-tailed Student's t test and shown as means ± SEM. N.S., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

See also Figure S6.

We then used dextran-4000-FITC (FITC-DX) to examine the intestinal barrier function of these mice. As shown in Figure 6E, mice from the DSS-treated groups showed a high concentration of FITC-DX in blood samples, indicating gut leakage in these animals. However, intervention with TFs significantly prevented the transport of FITC-DX from digestive organs into the circulatory system (reduced by 56.1%–77.5%, Figure 6E). Notably, administration of TFs did not alter the gut permeability of mice under normal conditions (Figure S6F). Because inflammation plays a pivotal role in colitis development of mouse model, we further performed qRT-PCR experiments, showing that TFs treatment significantly downregulated IL-6 and TNFα expressions in intestines of DSS-treated mice (Figures 6F and 6G).

To further analyze the pathological changes in the colon, we performed hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining assays. As shown in Figures 6H–6L and S6G–S6J, the DSS-induced severe epithelial damage was markedly ameliorated by TFs treatment in a dose-dependent manner. Scanning electron microscopy imaging of these intestinal samples further provided consistent results (Figures 6M-6Q′ and S6K-S6N′). Taken together, our findings indicated that TFs play a beneficial role in protecting intestinal barrier function in both insects and mammals.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the physiological functions of TFs in modulating intestinal homeostasis and longevity and the underlying molecular mechanisms. We showed that dietary supplementation with TFs positively contributes to the prevention of age-onset dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the delay of gut epithelial dysfunction, thus prolonging lifespan in Drosophila. Our in vitro and in vivo mechanistic studies revealed that TFs likely play a negative role in controlling the Imd signaling pathway by blocking the coalescence of Imd. Moreover, we found that DSS-induced colitis can be efficiently alleviated by TFs supplementation in CD-1 mice. Our results support the notion that TFs advantageously contribute to intestinal homeostasis in both invertebrates and vertebrates.

Dietary supplementation with theaflavins prolongs Drosophila lifespan

Tea consumption is popular worldwide and is second only to water consumption (Rothenberg and Zhang, 2019). Numerous studies have focused on the physiological functions of tea via both experimental and clinical approaches (Cameron et al., 2008; Niu et al., 2013; Peng et al., 2009; Rothenberg and Zhang, 2019; Spindler et al., 2013; Takemoto and Takemoto, 2018; Unno et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). It has been extensively shown that tea benefits health by lowering lipid levels and via anti-obesity effects, and the main functional compounds in tea are catechins, especially epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) (Abbas and Wink, 2009; Modernelli et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2018). Previous studies have also indicated that green tea and black tea can increase the health span and lifespan of fruit flies (Si et al., 2011; Wagner et al., 2015), worms (Fei et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2018), and rats (Imran et al., 2018; Niu et al., 2013), and the main regulatory mechanism is the effective prevention of oxidative stress by EGCG via modulation of ROS signals. However, whether TFs, as the characteristic “golden” compounds in black tea, play a role in regulating aging and lifespan remains largely unknown. This study provides compelling evidence indicating that TFs intervention is dispensable for impacting food intake, and long-term uptake of TFs via the diet significantly extends lifespan in both male and female fruit flies. These findings provide guidelines for further studies on the functions of TFs in mammalian longevity.

Theaflavins improve age-onset microbiota dysbiosis and promote intestinal homeostasis

Progressive imbalance of proliferative homeostasis and regenerative capacity is a hallmark of aging and age-onset diseases (Clark et al., 2015; Heintz and Mair, 2014; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018; Rera et al., 2012). Chronic inflammation is associated with the loss of homeostasis and increased cancer incidence in aging organisms (Bartke et al., 2019; Kapahi et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2020). This is particularly significant in barrier epithelia such as the intestinal epithelium (Guo et al., 2014; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018). With a model for the development of age-related dysplasia in the aging intestine, we demonstrated that improving host-commensal interactions in aging barrier epithelia could promote health and lifespan. We used a number of noninvasive approaches to assay intestinal function and microbiota dynamics during aging. First, the Smurf assay indicated a positive role of TFs in regulating epithelial barrier dysfunction during aging. Then, the immunostaining assay using several transgenic flies revealed that TFs delayed the over-proliferation of ISCs and turnover of differentiated cells. Finally, sequencing of the microbiome suggested that TFs downregulate the age-onset expansion of the intestinal commensal microflora. These results strongly indicated that TFs play a key role in delaying the aging process of the host by maintaining gut homeostasis.

Theaflavins alleviate excessive immune responses in the gut by negatively regulating Imd signaling

It has been suggested that the delicate balance between the gut immune function and microbiota has to be maintained to ensure long-term homeostasis of barrier epithelia (Guo et al., 2014; Maynard and Weinkove, 2018). Previous studies have also shown that chronic excessive inflammation in the gut is associated with age-related dysfunction in barrier epithelia and is a hallmark of aging (Clark et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2014; Ji et al., 2019). Thus, maintaining a healthy commensal population by preserving innate immune homeostasis in such epithelia is a promising approach to promote health and longevity (Bonfini et al., 2016; Broderick, 2016; Clark et al., 2015). To explore the molecular mechanisms by which TFs delay aging, we performed RNA-seq analysis using dissected intestines with or without TFs treatment. Our data suggested that the group of genes highly expressed in the intestines of control fruit flies compared with that of TFs-treated animals was enriched with genes classified as “immune response” genes. Further bioinformatic analysis and qRT-PCR assays revealed that the expression of Imd-related AMP genes was dramatically inhibited by dietary addition of TFs. The results from the CD-1 mouse experiments utilizing DSS to induce abnormal immune responses in the intestines further confirmed the notion that TFs function as protectors against intestinal inflammation.

Theaflavins suppress Imd signals by determining the amyloid assembly of Imd

How do TFs negatively regulate the Imd signaling pathway? Based on the results of transcriptome analysis, we found that TFs are dispensable for transcriptional regulation of the key factors in the Imd signaling pathway. Of interest, we observed apparent binding affinity of TFs with purified Imd protein by SPR assay, which suggested a probability that TFs might play a role in controlling Imd protein behavior or its post-translational modification process. Previous studies have highlighted a pivotal role of ubiquitination in Imd signal transduction (Kleino and Silverman, 2014; Myllymaki et al., 2014), and prevention of Imd ubiquitination results in profound shutting down of Imd signaling (Myllymaki et al., 2014; Thevenon et al., 2009). However, our in vitro and in vivo ubiquitination assays showed that TFs hardly affect the ubiquitination pattern of Imd. A recent study has shown that amyloid formation is required for activation of the Drosophila Imd pathway upon recognition of bacterial peptidoglycans (Kleino et al., 2017). Interestingly, our SDD-AGE and ThT binding assays suggested that the coalescence of Imd is prevented by TFs. Prevention of Imd aggregation by knocking down or mutation of Imd in gut cells apparently reversed the beneficial effects of TFs on lifespan extension. To further confirm our finding, it would be interesting to examine whether TFs are no more functional to extend lifespan in fruit fliers when the conserved cryptic RHIM (cRHIM, amino acids from the 118th to the 121th) motif of Imd is specifically knocked out or destroyed, based upon the finding that the cRHIM in the Imd is essential for its aggregation and amyloid formation (Kleino et al., 2017). Nevertheless, our study highlights a pivotal role of TFs in controlling intestinal homeostasis and the aging process, maybe through modulating Imd coalescence. Future studies should focus on exploring which residues or regions of Imd are bound by TFs and how this binding results in prevention of Imd condensation. Moreover, our findings in the mammalian system indicated that TFs could effectively protect the colon against inflammation caused by the exogenous poisonous chemical DSS, suggesting a conserved regulatory role of TFs in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. It is worthwhile to investigate whether TFs play a role in governing protein assembly in mammalian tissues.

Limitations of the study

In this study, we identified a biological function of TFs as an intestine protector in both Drosophila and mice. In vitro mechanistic investigations suggested that TFs are able to bind to Drosophila Imd and regulate its aggregation assembly, which is likely a mechanism by which TFs positively contribute to the prevention of age-onset intestinal leakage and extension of fruit fly lifespan. However, whether dietary supplementation of TFs delays Drosophila aging directly through restricting the formation of Imd aggregate remains elusive because of lacking of in vivo data from fly lines that only aggregation of Imd is blocked. Thus, construction of imd mutants where the cryptic RHIM (cRHIM, amino acids from the 118th to the 121th) motif of Imd is specifically knocked out or destroyed would be a useful tool to prove this conclusion. Moreover, future investigation should focus on exploring which residues or regions of Imd are bound by TFs and how this binding results in modulation of Imd condensation.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Zhongwen Xie (zhongwenxie@ahau.edu.cn).

Materials availability

All Drosophila lines and reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request. The raw Illumina sequencing data from the RNA-seq generated during this study are deposited in SRA database under accession number PRJNA694009 at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA694009).

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a key joint grant for regional innovation from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to Z. X. (grant number U19A2034), a key grant for University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province to Z. X. (grant number GXXT-2019-049), and a grant for supporting the animal core facility at Anhui Agricultural University from the Department of Sciences and Technology of Anhui Province.

Author contributions

Q. C., S. J., and Z. X. designed the experiments. Q. C., S. J., M. L., S. Z., X. Z., H. G., S. D., and J. Z. performed the experiments. Q. C., S. J., and Z. X. performed the data analyses. Q. C., S. J., and Z. X. wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the submission.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 19, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102150.

Supplemental information

References

- Abbas S., Wink M. Epigallocatechin gallate from green tea (Camellia sinensis) increases lifespan and stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Planta Med. 2009;75:216–221. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavez S., Vantipalli M.C., Zucker D.J., Klang I.M., Lithgow G.J. Amyloid-binding compounds maintain protein homeostasis during ageing and extend lifespan. Nature. 2011;472:226–229. doi: 10.1038/nature09873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barardo D., Newby D., Thornton D., Ghafourian T., Magalhaes J., Freitas A. Machine learning for predicting lifespan-extending chemical compounds. Aging. 2017;9:1721–1736. doi: 10.18632/aging.101264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartke A., Evans T., Musters C.J.M. Anti-aging interventions affect lifespan variability in sex, strain, diet and drug dependent fashion. Aging. 2019;11:4066–4074. doi: 10.18632/aging.102037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfini A., Liu X., Buchon N. From pathogens to microbiota: how Drosophila intestinal stem cells react to gut microbes. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016;64:22–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick N.A. Friend, foe or food? Recognition and the role of antimicrobial peptides in gut immunity and Drosophila-microbe interactions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016;371:20150295. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick N.A., Buchon N., Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. mBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01117-14. e01117-01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N., Broderick N.A., Lemaitre B. Gut homeostasis in a microbial world: insights from Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:615–626. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A.R., Anton S., Melville L., Houston N.P., Dayal S., McDougall G.J., Stewart D., Rena G. Black tea polyphenols mimic insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signalling to the longevity factor FOXO1a. Aging Cell. 2008;7:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capo F., Wilson A., Di Cara F. The intestine of Drosophila melanogaster: an emerging versatile model system to study intestinal epithelial homeostasis and host-microbial interactions in humans. Microorganisms. 2019;7:336. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7090336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso C., Accardi G., Virruso C., Candore G. Sex, gender and immunosenescence: a key to understand the different lifespan between men and women? Immun. Ageing. 2013;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R.I., Salazar A., Yamada R., Fitz-Gibbon S., Morselli M., Alcaraz J., Rana A., Rera M., Pellegrini M., Ja W.W. Distinct shifts in microbiota composition during Drosophila aging impair intestinal function and drive mortality. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1656–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilov A., Shaposhnikov M., Shevchenko O., Zemskaya N., Zhavoronkov A., Moskalev A. Influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on Drosophila melanogaster longevity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19428–19444. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilliane C., Suelen F., Jaqueline V., Welligton L.B. Valeriana officinalis and melatonin: evaluation of the effects in Drosophila melanogaster rapid iterative negative geotaxis (RING) test. J. Med. Plants Res. 2017;11:703–712. [Google Scholar]

- Enge M., Arda H.E., Mignardi M., Beausang J., Bottino R., Kim S.K., Quake S.R. Single-cell analysis of human pancreas reveals transcriptional signatures of aging and somatic mutation patterns. Cell. 2017;171:321–330 e314. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Lam S.M., Xin J., Yang X., Liu Z., Liu Y., Wang Y., Shui G., Huang X. Drosophila TRF2 and TAF9 regulate lipid droplet size and phospholipid fatty acid composition. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei T., Fei J., Huang F., Xie T., Xu J., Zhou Y., Yang P. The anti-aging and anti-oxidation effects of tea water extract in Caenorhabditis elegans. Exp. Gerontol. 2017;97:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillou A., Troha K., Wang H., Franc N.C., Buchon N. The Drosophila CD36 homologue croquemort is required to maintain immune and gut homeostasis during development and aging. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005961. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Karpac J., Tran S.L., Jasper H. PGRP-SC2 promotes gut immune homeostasis to limit commensal dysbiosis and extend lifespan. Cell. 2014;156:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz C., Mair W. You are what you host: microbiome modulation of the aging process. Cell. 2014;156:408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudry B., de Goeij E., Mineo A., Gaspar P., Hadjieconomou D., Studd C., Mokochinski J.B., Kramer H.B., Plaçais P.-Y., Preat T. Sex differences in intestinal carbohydrate metabolism promote food intake and sperm maturation. Cell. 2019;178:901–918.e916. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imler J.L. Overview of Drosophila immunity: a historical perspective. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014;42:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran A., Arshad M.U., Arshad M.S., Imran M., Saeed F., Sohaib M. Lipid peroxidation diminishing perspective of isolated theaflavins and thearubigins from black tea in arginine induced renal malfunctional rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17:157. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0808-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja W.W., Carvalho G.B., Mak E.M., Rosa N.N., Fang A.Y., Liong J.C., Brummel T., Benzer S. Prandiology of Drosophila and the CAFE assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:8253–8256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702726104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S., Luo Y., Cai Q., Cao Z., Zhao Y., Mei J., Li C., Xia P., Xie Z., Xia Z. LC domain-mediated coalescence is essential for otu enzymatic activity to extend Drosophila lifespan. Mol. Cell. 2019;74:363–377 e365. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P., Kaeberlein M., Hansen M. Dietary restriction and lifespan: lessons from invertebrate models. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017;39:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleino A., Ramia N.F., Bozkurt G., Shen Y., Nailwal H., Huang J., Napetschnig J., Gangloff M., Chan F.K., Wu H. Peptidoglycan-sensing receptors trigger the formation of functional amyloids of the adaptor protein imd to initiate Drosophila NF-kappaB signaling. Immunity. 2017;47:635–647.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleino A., Silverman N. The Drosophila IMD pathway in the activation of the humoral immune response. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014;42:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo A., Narumi K., Okuhara K., Takahashi Y., Furugen A., Kobayashi M., Iseki K. Black tea extract and theaflavin derivatives affect the pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin by modulating organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) 2B1 activity. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2019;40:302–306. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D., Rizvi S.I. Black tea supplementation augments redox balance in rats: relevance to aging. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;123:212–218. doi: 10.1080/13813455.2017.1302963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Huang P., Li X., Yin D., Ma Z., Wang H., Song H. Tankyrase mediates K63-linked ubiquitination of JNK to confer stress tolerance and influence lifespan in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2018;25:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lo C.Y., Pan M.H., Lai C.S., Ho C.T. Black tea: chemical analysis and stability. Food Funct. 2013;4:10–18. doi: 10.1039/c2fo30093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Su F., Li Q., Zhang J., Li Y., Tang T., Hu Q., Yu X.Q. Pattern recognition receptors in Drosophila immune responses. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2020;102:103468. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2019.103468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard C., Weinkove D. The gut microbiota and ageing. Subcell Biochem. 2018;90:351–371. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-2835-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modernelli A., Naponelli V., Giovanna Troglio M., Bonacini M., Ramazzina I., Bettuzzi S., Rizzi F. EGCG antagonizes Bortezomib cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells by an autophagic mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15270. doi: 10.1038/srep15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moger-Reischer R.Z., Snider E.V., McKenzie K.L., Lennon J.T. Low costs of adaptation to dietary restriction. Biol. Lett. 2020;16:20200008. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllymaki H., Valanne S., Ramet M. The Drosophila imd signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2014;192:3455–3462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumovski N., Foscolou A., D'Cunha N.M., Tyrovolas S., Chrysohoou C., Sidossis L.S., Rallidis L., Matalas A.L., Polychronopoulos E., Pitsavos C. The association between green and black tea consumption on successful aging: a combined analysis of the ATTICA and MEDiterranean ISlands (MEDIS) epidemiological studies. Molecules. 2019;24:1862. doi: 10.3390/molecules24101862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson J.K., Holmes E., Kinross J., Burcelin R., Gibson G., Jia W., Pettersson S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y., Na L., Feng R., Gong L., Zhao Y., Li Q., Li Y., Sun C. The phytochemical, EGCG, extends lifespan by reducing liver and kidney function damage and improving age-associated inflammation and oxidative stress in healthy rats. Aging Cell. 2013;12:1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/acel.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C., Chan H.Y., Li Y.M., Huang Y., Chen Z.Y. Black tea theaflavins extend the lifespan of fruit flies. Exp. Gerontol. 2009;44:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rera M., Bahadorani S., Cho J., Koehler C.L., Ulgherait M., Hur J.H., Ansari W.S., Lo T., Jr., Jones D.L., Walker D.W. Modulation of longevity and tissue homeostasis by the Drosophila PGC-1 homolog. Cell Metab. 2011;14:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rera M., Clark R.I., Walker D.W. Intestinal barrier dysfunction links metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging to death in Drosophila. PNAS. 2012;109:21528–21533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215849110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg D.O., Zhang L. Mechanisms underlying the anti-depressive effects of regular tea consumption. Nutrients. 2019;11:1361. doi: 10.3390/nu11061361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J.H., Ha E.M., Lee W.J. Innate immunity and gut-microbe mutualism in Drosophila. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2010;34:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J.H., Ha E.M., Oh C.T., Seol J.H., Brey P.T., Jin I., Lee D.G., Kim J., Lee D., Lee W.J. An essential complementary role of NF-kappaB pathway to microbicidal oxidants in Drosophila gut immunity. EMBO J. 2006;25:3693–3701. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A.M., Resnik-Docampo M., Ulgherait M., Clark R.I., Shirasu-Hiza M., Jones D.L., Walker D.W. Intestinal snakeskin limits microbial dysbiosis during aging and promotes longevity. iScience. 2018;9:229–243. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si H., Fu Z., Babu P.V., Zhen W., Leroith T., Meaney M.P., Voelker K.A., Jia Z., Grange R.W., Liu D. Dietary epicatechin promotes survival of obese diabetic mice and Drosophila melanogaster. J. Nutr. 2011;141:1095–1100. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.134270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler S.R., Mote P.L., Flegal J.M., Teter B. Influence on longevity of blueberry, cinnamon, green and black tea, pomegranate, sesame, curcumin, morin, Pycnogenol, quercetin and taxifolin fed isocalorically to long-lived, F1 hybrid mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2013;16:143–151. doi: 10.1089/rej.2012.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats S., Rimbach G., Kuenstner A., Graspeuntner S., Rupp J., Busch H., Sina C., Ipharraguerre I.R., Wagner A.E. Lithocholic acid improves the survival of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018;62:e1800424. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201800424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto M., Takemoto H. Synthesis of theaflavins and their functions. Molecules. 2018;23:918. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen J.M., Barry W.E., Cox J., Thummel C.S. Methods for studying metabolism in Drosophila. Methods. 2014;68:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevenon D., Engel E., Avet-Rochex A., Gottar M., Bergeret E., Tricoire H., Benaud C., Baudier J., Taillebourg E., Fauvarque M.O. The Drosophila ubiquitin-specific protease dUSP36/Scny targets IMD to prevent constitutive immune signaling. Cell Host microbe. 2009;6:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno K., Pervin M., Taguchi K., Konishi T., Nakamura Y. Green tea catechins trigger immediate-early genes in the Hippocampus and prevent cognitive decline and lifespan shortening. Molecules. 2020;25:1484. doi: 10.3390/molecules25071484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valanne S., Wang J.H., Ramet M. The Drosophila Toll signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 2011;186:649–656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar M., Aitken J.D., Carvalho F.A., Cullender T.C., Mwangi S., Srinivasan S., Sitaraman S.V., Knight R., Ley R.E., Gewirtz A.T. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A.E., Peigholdt S., Rabe D., Baenas N., Schloesser A., Eggersdorfer M., Stocker A., Rimbach G. Epigallocatechin gallate affects glucose metabolism and increases fitness and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Oncotarget. 2015;6:30568–30578. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Wang Y., Han Y., Henderson S., Majeska R., Weinbaum S., Schaffler M. In situ measurement of solute transport in the bone lacunar-canalicular system. PNAS. 2005;102:11911–11916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505193102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y.Z., Yang M., Xiao Y., Guo Q., Huang Y., Li C.J., Cai D., Luo X.H. Reducing hypothalamic stem cell senescence protects against aging-associated physiological decline. Cell Metab. 2020;31:534–548 e535. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L.G., Chen Y.J., Tong J.W., Gong Y.S., Huang J.A., Liu Z.H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate promotes healthy lifespan through mitohormesis during early-to-mid adulthood in Caenorhabditis elegans. Redox Biol. 2018;14:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T., Sagisaka M., Ikeda R., Nakamura T., Matsuda N., Ishii T., Nakayama T., Watanabe T. The human bitter taste receptor hTAS2R39 is the primary receptor for the bitterness of theaflavins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014;78:1753–1756. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2014.930326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Hu Z., Lu M., Li P., Tan J., Chen M., Lv H., Zhu Y., Zhang Y., Guo L. Application of metabolomics profiling in the analysis of metabolites and taste quality in different subtypes of white tea. Food Res. Int. 2018;106:909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R., Li X., Li L., Zhang H. Theaflavins alleviate sevoflurane-induced neurocytotoxicity via Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int. J. Neurosci. 2020;130:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2019.1667788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R., Silverman N., Hong M., Liao D.S., Chung Y., Chen Z.J., Maniatis T. The role of ubiquitination in Drosophila innate immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:34048–34055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Lead Contact upon reasonable request. The raw Illumina sequencing data from the RNA-seq generated during this study are deposited in SRA database under accession number PRJNA694009 at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA694009).