Abstract

Background:

The growing use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) among adolescents is a public health concern. Taxation of these products is a viable approach to reduce ENDS use, particularly among adolescents. Opponents of taxation posit that it puts specialty retailers (ie, vape shops) out of business, thereby reducing availability of ENDS for adult smokers seeking harm reduction. Pennsylvania enacted substantial ENDS taxes in October 2016. This study sought to examine (1) the prevalence of Pennsylvania vape shops before and after ENDS taxes were enacted and (2) ENDS retail licensing compliance among vape shops.

Methods:

We employed standardized searches for vape shops in Pennsylvania on the Yelp business-listing platform a month prior to and for 18 consecutive months following the imposition of ENDS taxes. We then compared listings to a public database of ENDS-related retail licenses to determine compliance status.

Results:

The number of listed vape shops increased in a linear fashion by a magnitude of 23%. In addition, when we compared a final listing of retailers to data from the state tax authority, we found roughly a quarter (22%-29%) of vape shops to be noncompliant with maintaining a valid ENDS retail license.

Conclusions:

Overall, ENDS taxation in Pennsylvania has not appeared to reduce prevalence of vape shops as anticipated. However, stricter enforcement of the tax law is necessary to ensure compliance among retailers. These findings have implications for implementation and enforcement of ENDS tax policy nationwide, including states that currently lack such policies.

Keywords: Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems, Public Health Policy, Taxation, Compliance

Background

Use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), also known as e-cigarettes or “vapes,” among youth and young adults has become a public health concern.1 Electronic nicotine delivery systems’ use among cigarette-naïve individuals is a risk factor for cigarette initiation and increasingly high rates of youth ENDS use have emphasized the need for new policy interventions.2-4 Research indicates that nicotine can have adverse effects on the developing adolescent brain, and that adolescent use of ENDS is associated with future cigarette initiation.2,5 A common point of discussion is the harm reduction potential of ENDS for aiding in cigarette smoking cessation, although trying to quit smoking cigarettes is not a primary reason for using ENDS among youth.1 For adult smokers trying to quit, strong independent studies have demonstrated the potential of ENDS as a cigarette cessation tool, though recent systematic reviews have been inconclusive.6,7 The health impact of ENDS is still being investigated and debated, although recent research suggests that some nicotine-containing products may be associated with the recent e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) outbreak.8 Likewise, although there are no known studies examining ENDS use among pregnant women, the negative effects of nicotine on pregnancy and the developing fetus are well-documented.9 Still, public health regulations aimed at reducing adolescent use have faced opposition due to their potentially negative impact on cigarette smoking adults who wish to use e-cigarettes as a potential smoking cessation tool.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems present new challenges to U.S. national, state, and municipal tobacco control policies.

In addition to point-of-sale youth access regulations (eg, age verification), other common regulatory approaches to tobacco control include use restrictions (eg, clean indoor air regulations), regulation of flavoring (eg, limiting flavors to tobacco and menthol only) and labeling (eg, text or graphic warning labels on products, disclosure of ingredients), and imposition of excise taxes.10 Over the past 50 years, one of the most effective tobacco control strategies has been increased taxes on tobacco products.11 This may also be true for ENDS: a recent systematic review determined that a 10% increase in ENDS price corresponded to an 18% decrease in quantity consumed.12 Higher prices of disposable ENDS have also been associated with lower prevalence of adolescent use.13 In addition, tax revenues can fund cessation programs, tobacco policy enforcement efforts, and public health education programs that serve to decrease tobacco use overall.11 As of December 2019, 21 U.S. states and the District of Columbia impose a tax on ENDS, e-liquids, or both.14 In October 2016, Pennsylvania (PA) implemented one of the broadest taxation approaches by imposing a 40% tax on the wholesale value of both ENDS and e-liquids, and by instituting a retailer license requirement to monitor physical establishments selling these products.15,16

Little is currently known about retailer compliance with taxation or licensing regulations in PA. For example, while there are penalties of up to US$1000 and 60 days in prison for selling or possessing untaxed products,16 it is unclear how stringent enforcement has been on retailers. Thus, retail licensing presents a crucial administrative framework, allowing for systematic monitoring of known retailers. This also affords opportunities to implement more targeted measures such as capping the number of available licenses or limiting retailer proximity to schools and parks.17-19 Several states also have considered, or are considering, legislation to limit tobacco/ENDS sales by type of establishment (eg, pharmacies) or in particular areas (eg, residential zones).19 Implementation and enforcement of such approaches relies on effective retail licensing infrastructure and compliance. In PA, retail licensing requirements for ENDS went into effect in July 2016.17 Retail licensing is required for all tobacco product and ENDS retailers in PA. Separate licenses are available for tobacco retailers, “Other Tobacco Product” retailers (OTP; including ENDS), combined tobacco-OTP retailers, and wholesalers. Retail licenses are renewed every March 1 for a nominal fee of US$25.20 However, the 40% wholesale tax is a nontrivial amount and an initial “floor tax” of all existing OTP inventory was due from retailers within 90 days of the tax going into effect.21 Thereafter, wholesalers collect and pay the tax, thus increasing the cost when retailers purchase new inventory.

Electronic nicotine delivery systems’ retailers and industry advocates feared that the tax on ENDS products would “doom” vape shops in PA and cause widespread closures.22,23 Specifically, industry advocates have claimed that more than 100 specialty retailers (ie, vape shops) have been put out of business by these tax policies and have also expressed fears that taxation will ultimately “decimate” the economic landscape for vape shops in PA.22,23 These concerns were consistent across other states as well, with advocacy groups that strongly oppose these regulations arguing that they decimate businesses and reduce availability of ENDS as harm reduction or cessation tools for cigarette-addicted adults.24 However, there has been little empirical evidence to indicate that this specific tax—or state taxes more broadly—have had a substantial overall impact in the ENDS retailer market. Furthermore, as little is known about ENDS retailer tax compliance, it is unclear how frequently retailers might attempt to evade taxes by buying from noncompliant online wholesalers, having orders shipped to out-of-state addresses, or using other measures. As such, the best available proxy measure that we currently have available for tax compliance is retail licensing compliance.

Therefore, we developed a strategy to monitor the prevalence of vape shops in PA 1 month prior to and in the 18 months following imposition of this ENDS tax. Our study drew upon publicly available data to (1) examine the prevalence of PA vape shops in the wake of the tax and (2) to examine retailers’ registration compliance by comparing observed listings to state records of OTP retail licenses.

Methods

The Yelp business-listing platform has been successfully used in studies tracking vape shop prevalence in New Jersey and Florida.25,26 We used Yelp to track vape shop prevalence in PA, an ideal test bed for examining this type of tax policy as a political microcosm of the United States with an active health policy landscape.10

Data collection began in September 2016 (1 month before the tax went into effect) and continued at monthly intervals through April 2018. Study data were retrieved directly from the Yelp Application Programming Interface (API; version 2), using a standardized Python script, to ensure reproducibility and inclusiveness of search strategies over time.27 New business listings are added to Yelp from publicly listed address information and are updated by business owners as well as Yelp users.28 While this improves detection over relying on business owners alone, there is no benchmark of how fast detection takes place, either broadly or within business categories. Updates are presumed to happen relatively quickly, given Yelp’s popularity with 36 million unique mobile users per month and prompts users receive to verify information for locations they visit.29 As such, 18 months of posttax follow-up should be ample time to comprehensively detect openings and closures in the wake of the PA tax.

Our searches centered within 37 census regions with 25-mile search radii, systematically covering most of PA. Search terms included vape, vapor, vaping, ecig, e-cig, and e-cigarette. We obtained Yelp metadata to confirm that establishments were categorically listed as “vape shops” and were considered open for business. Consistent with best-practice recommendations, and to maintain a narrow focus, we excluded vape shops that were cross-listed as “head shops” (ie, selling cannabis paraphernalia) or “tobacco shops” by Yelp.30 Businesses can be reclassified by the business owner or users of the platform and so may not appear as a vape shop across all consecutive searches. To account for this, we considered an establishment as a currently operating (ie, open) vape shop at a particular time point if it was classified as such at both a preceding and a future time point. Otherwise, we treated vape shops that failed to appear in consecutive searches as closed as of the final valid data point.

Establishments that we identified as vape shops at the final time point (April 2018) were cross-referenced on the opendataPA online portal,31 a comprehensive listing of all establishments with current retail permits for “OTP” to determine whether they had a valid retail permit to sell ENDS products. Because the opendataPA database contains nearly 18 000 records in total, a listing of the most likely potential matches to Yelp listings was first generated using a standard text comparison algorithm prior to human adjudication.32 We used the Python difflib package to cross-reference textual similarities between each Yelp listing and a subset of over 11 000 establishments licensed to sell ENDS products in the March 1, 2018, through February 28, 2019, licensing year. We refreshed the licensing data from the database in July 2018, to ensure adequate coverage of lag time in database updates or license applications that may have been submitted late. This licensing data included a broad scope of establishments, such as convenience stores, and did not differentiate business categories (eg, vape shops were grouped among all other business categories). Therefore, we set difflib to match Yelp listings to licensing data based on name and address fields, to rank them by similarity. Then, 2 human coders collaboratively reviewed and compared the top 3 license database matches to each Yelp establishment. Yelp listings were classified as “matched” (similar name and address in database), “possible match” (similar name or address, but not both), or “no match” (unable to locate a similar database record). We further confirmed current operating status of vape shops not matched to a license by telephoning establishments and searching online for a recently active website or social media account. In this way, we were able to obtain better ground truth of open vape shops that may be operating without current licenses.

Results

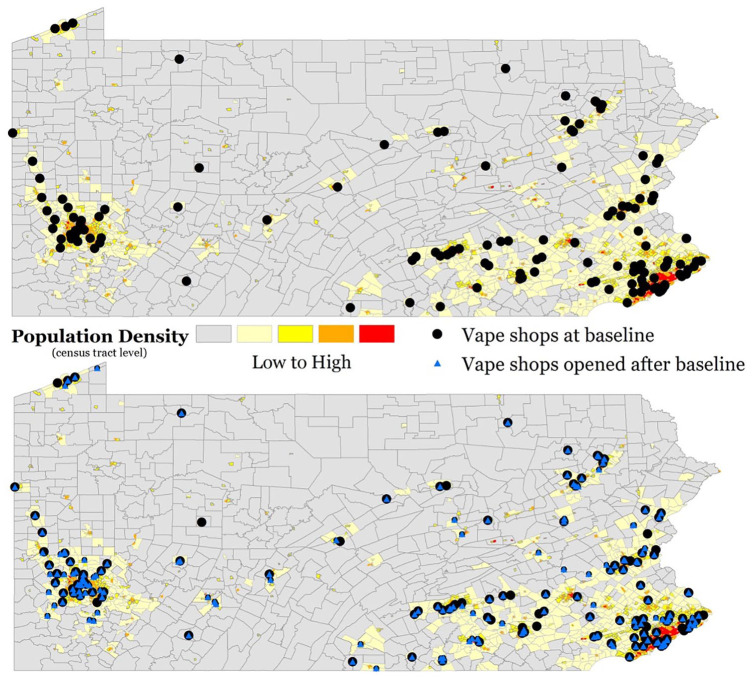

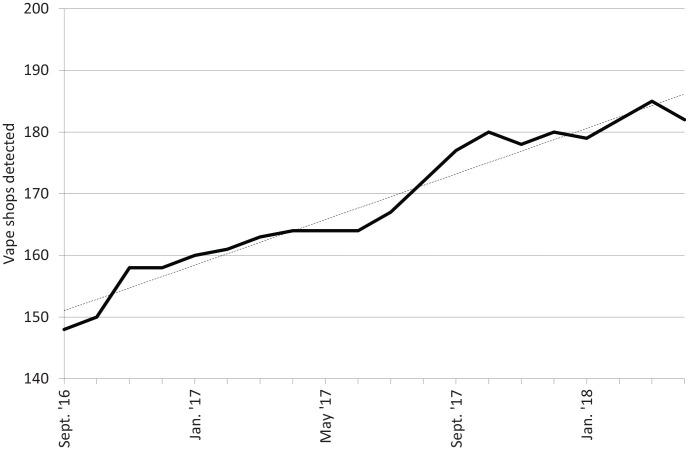

In September 2016, a month prior to taxation, there were 148 open vape shops (Figure 1). By April 2018, this number increased to 182, of which 62 were new listings over this period (Figure 1). Controlling for shops that opened or closed during this time period resulted in a net increase of 34 (23%); the total number of vape shops increased in a linear fashion across the data collection period (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Vape shops at initial data collection (September 2016) and those present at final data collection (April 2018) based on publicly available data on Yelp.

Figure 2.

Net change in prevalence of vape shops detected in PA from September 2016 to April 2018 based on publicly available data on Yelp. Dashed line indicates linear interpolation (slope m = 1.85). PA indicates Pennsylvania.

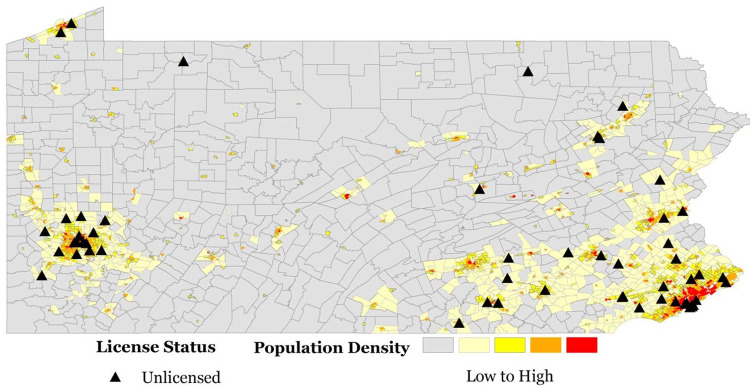

Of the 182 final vape shops, 115 (63%) were confirmed as having a matching retail license and were assumed to be currently operating. An additional 12 (7%) were matched to a possible license by either similar business name or address. For the remaining 55 (30%) identified as having no current license of record, we were able to confirm current open status for 36: 26 by phone, 6 by recent social media activity, and 4 that maintain an active website (19 could not be confirmed as currently operating). For the 12 shops that were possibly matched with a license, an additional 10 were confirmed open by telephone call (2 could not be confirmed as currently operating). Thus, a total of 21 retailers could not be confirmed as currently operating and were removed from the following calculations (adjusted n = 161 vape shops currently operating). From this, we concluded that at least 22% (36/161) and up to 29% (46/161) of vape shops in our sample were operating without a listed OTP retail license (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Vape shops identified as unlicensed to retail “other tobacco products” (ie, ENDS). ENDS indicates electronic nicotine delivery systems.

Discussion

Owners of vape shops generally believe that a primary mission of their business is to assist customers in transitioning away from traditional cigarettes.24 Therefore, it is understandable that vape shop owners view regulation and taxation of their shops and the vaping market to be a threat to their business, livelihood, and mission. However, this study of vape shops in PA found that there was a net increase in the number of vape shops in the 18 months following the new tax law, which introduced a new 40% tax on the wholesale value of ENDS products.15,16 It also found that a substantial proportion of vape shops appear to be operating without valid retail licenses. The results obtained through this study suggest that while these regulatory measures may not present excessive burden overall, a substantial number of vape shop operators may evade such regulation.

There was a net increase in the total prevalence of vape shops: more new shops opened than the total number that closed down during the study. While it is possible that some vape shops closed because of increases in taxation, it is also possible that market saturation played a role. Indeed, the number of vape shops across the United States has been increasing; Dai and Hao identified 9945 vape shops nationally in 2016—a 3-fold increase from 2013—demonstrating an increasingly competitive market for existing shops.33

In addition, as ENDS with disposable cartridges, such as the JUUL brand, have surged in popularity, these products are becoming more widely available.34 These devices are frequently sold at convenience stores, pharmacies, discount/dollar stores, and mass merchandise stores, which may further divert potential revenue from specialty vape retailers.35 This is particularly likely during the timeframe in which our data were collected, as the JUUL brand increased its market share more than 5-fold during 2016 to 2017.35 Furthermore, this substantial growth indicator does not account for this brand’s direct-to-consumer online sales, which were heavily marketed on a variety of online social media platforms over this time period.36

It is also possible that customer preferences led to the closure of some vape shops. Similar to hookah lounges, prominent vape shops tend to market themselves as venues in which users can socialize, sample e-liquids, and modify vapor and e-cigarette devices.37 Research indicates that customers have expectations that employees have the ability to build and fix vaping devices and maintain a “bar type” atmosphere.38 Shops not meeting these expectations may fall prey to other, more competitive vape shops. Therefore, even for vape shops that did close during over the duration of this study, a variety of other market forces, other than new tax laws, may have been influential.

Given the limitation of our study primarily relying on data from the Yelp platform, some of these market factors (eg, convenience store retailers, online sales) remain undetected. As this platform has been used in similar statewide studies,25,26 these findings nonetheless represent a contribution to understanding general trends in vape shops. Because there are likely to be other vape shops not listed on the Yelp platform, this study is likely to have underestimated the true prevalence in PA.

Another important finding of this work was that a relatively high number of vape shops did not match a valid “OTPs” retail license. Enforcement of ENDS tax administration in PA has been difficult due to the inability to track out-of-state suppliers and lack of compliance by in-state retailers.39 Other states have had similar difficulties, leading to a recommendation for adopting statutory enforcement and noncompliance penalties.39 For example, Louisiana allocates a portion of their tax revenue toward a “Tobacco Regulation Enforcement Fund” for the Office of Alcohol and Tobacco Control to take on the additional burden of monitoring ENDS retailers.39 At least 26 states have retail licensing requirements for ENDS.14 Instituting such licenses and maintaining a database of associated retailers is an initial step toward monitoring which establishments may be delinquent on other regulations, including ENDS tax imposition. However, our data indicate that a substantial proportion of vape shop operators may fail to maintain such a license in the absence of proactive enforcement. Additional monitoring approaches, such as we used to compare publicly available Yelp data to licensing data, offer an opportunity to detect and monitor cases of retailer noncompliance. This is one possible tool that public health agencies might consider for enhancing enforcement efforts in this realm.

Despite the challenges in implementing and enforcing such regulations, PA has successfully generated annual revenue from the OTP tax since its inception in October 2016. In fiscal year ending June 30, 2017, which included the initial floor tax and partial-year wholesale tax revenue, the state collected US$83.9 million. In the first full year of wholesale tax collection (2017-2018), revenues were upward of US$119 million, which increased to nearly US$130 million in the subsequent year (2018-2019).40 Although this is a small proportion of the state’s overall tax revenues of approximately US$34 billion, it nonetheless reflects a sizable 40% increase to the consumer price of ENDS products. Although there are not current data to tie this tax to a direct reduction in ENDS use in the state, previous studies of ENDS pricing effects indicate that an expected reduction in ENDS use is plausible.12,13 However, ENDS users may seek out ways to avoid the tax markup on ENDS by purchasing devices online or seeking out retailers that buy and sell the device components separately (to avoid paying wholesale tax on fully assembled ENDS devices). This particular approach of selling tax-free ENDS components has been deemed legal in a case brought before PA Commonwealth Court, leading to additional loopholes in the comprehensive taxation of ENDS.41

Future research might examine these emerging trends in light of device choices among adolescent versus young adult ENDS users. For example, if nicotine naïve adolescents are unlikely to go through to additional effort of assembling device components to avoid tax-related costs, then closing this legal loophole might be a relatively low public health priority. Whereas with younger ENDS users gravitating toward popular, prebuilt “vape stick” devices such as JUUL, more attention may be needed to strongly enforce the tax for online or out-of-state purchasing of devices. As such, it will be important for future research to investigate how particular types of ENDS devices and users are affected by tax policies so that public health priorities and enforcement can be tailored to have maximum impact on reducing ENDS use among nicotine naïve youth.

Implications

Although increased taxes on ENDS may be an effective method of reducing adolescent ENDS use, public health regulations have faced opposition due to their potentially negative impact on current adult smokers. However, the findings of this study indicating increased prevalence of vape shops in PA despite a strong new taxation should alleviate some of those concerns. As these products continue to grow in popularity, advocacy groups in support and opposition of ENDS taxation are likely to become increasingly vocal. Policymakers in Pennsylvania have indicated that they generally do not know enough about ENDS,42 and education around health effects and potential impacts of taxation approaches may help inform decision-making. Without rigorous studies of policy impact, these important policy decisions may be approached with inadequate information based on anecdotal reports.42 Therefore, studies such as this may help provide new insight into the ongoing policy debate and public health response around taxation of ENDS products. This study is particularly timely because only 21 of 50 U.S. states currently levy taxes on ENDS products, though others are considering such a tax.14 An additional public health benefit is that tax revenues can fund cessation programs, tobacco policy enforcement efforts, and public health education programs that further serve to decrease habitual use of tobacco and associated nicotine products.11

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of the published work. JBC and MCT were primarily responsible for data collection and analysis. ZMD conducted geospatial analysis and developed corresponding figures. JES and MSW contextualized public health policy activity related to this scope of work. AEJ and BAP provided overall research supervision and mentorship. The authors further acknowledge and thank research assistants Charis Williams and Tabitha Yates for their dilligent work in canvassing online activity and contacting vape shops to confirm operating status, under the direc supervision of JBC.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jason B Colditz  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2811-841X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2811-841X

Jaime E Sidani  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5411-8755

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5411-8755

References

- 1. Office of the Surgeon General. E-cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA takes new steps to address epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, including a historic action against more than 1,300 retailers and 5 major manufacturers for their roles perpetuating youth access. FDA News Release. September 11, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm620184.htm. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 4. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Companies cease sales of e-liquids with labeling or advertising that resembled kid-friendly foods following FDA, FTC warnings. FDA News Release. August 23, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm618169.htm. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 5. England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA. Nicotine and the developing human: a neglected element in the electronic cigarette debate. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49:286-293. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malas M, van der Tempel J, Schwartz R, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:1926-1936. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. El Dib R, Suzumura EA, Akl EA, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems and/or electronic non-nicotine delivery systems for tobacco smoking cessation or reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012680. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christiani DC. Vaping-induced acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:960-962. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1912032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cardenas V, Fischbach L, Chowdhury P. The use of electronic nicotine delivery systems during pregnancy and the reproductive outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:52. doi: 10.18332/tid/104724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Colditz JB, Ton JN, James AE, Primack BA. Toward effective water pipe tobacco control policy in the United States: synthesis of federal, state, and local policy texts. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31:302-309. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.150218-QUAL-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/full-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jawad M, Lee JT, Glantz S, Millett C. Price elasticity of demand of non-cigarette tobacco products: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2018;27:689-695. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parks MJ, Kingsbury JH, Boyle RG, Choi K. Behavioral change in response to a statewide tobacco tax increase and differences across socioeconomic status. Addict Behav. 2017;73:209-215. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Public Health Law Center. U.S. E-cigarette Regulation: A 50-State Review. Saint Paul, MN: Public Health Law Center; 2019. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review. Accessed March 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15. PA Department of Revenue. Tobacco Products Bulletin 16-04. Harrisburg, PA: PA Department of Revenue; 2016. https://www.revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/TaxLawPoliciesBulletinsNotices/TaxBulletins/TobaccoProducts/Documents/tobacco_products_bulletin_16-04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pennsylvania General Assembly. Act 84 of 2016. https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/li/uconsCheck.cfm?yr=2016&sessInd=0&act=84. Published 2016.

- 17. Marynak K, Kenemer B, King BA, Tynan MA, MacNeil A, Reimels E. State laws regarding indoor public use, retail sales, and prices of electronic cigarettes—U.S. states, Guam, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands, September 30, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1341-1346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6649a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farrelly MC, Chaloupka FJ, Berg CJ, et al. Taking stock of tobacco control program and policy science and impact in the United States. J Addict Behav Ther. 2017;1:8 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30198028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luke DA, Sorg AA, Combs T, et al. Tobacco retail policy landscape: a longitudinal survey of US states. Tob Control. 2016;25:i44-i51. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. PA Department of Revenue. Other tobacco products tax. http://www.revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/TaxTypesandInformation/OTPT/Pages/default.aspx. Published 2017. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 21. PA Department of Revenue. 2016 Tobacco Products and E-cigarette Floor Tax Return (REV-1141). Harrisburg, PA: PA Department of Revenue; 2016. https://www.revenue.pa.gov/FormsandPublications/FormsforBusinesses/OTP/Documents/2016_rev-1141.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22. McDaniel J. Vape tax brings in millions—and is said to close over 100 Pa. businesses. The Philadelphia Inquirer. September 5, 2017. http://www.philly.com/philly/news/pennsylvania/vape-tax-brings-in-millions-and-closes-over-100-pa-businesses-20170905.html. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 23. Tierney J. Vape tax dooms dozens of shops across Pennsylvania. Trib Live. September 24, 2017. http://triblive.com/local/westmoreland/12756449-74/vape-tax-dooms-dozens-of-shops-across-pennsylvania. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 24. Nayak P, Kemp CB, Redmon P. A qualitative study of vape shop operators’ perceptions of risks and benefits of e-cigarette use and attitude toward their potential regulation by the US Food and Drug Administration, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, or North Carolina, 2015. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E68. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giovenco D, Duncan D, Coups E, Lewis M, Delnevo C. Census tract correlates of vape shop locations in New Jersey. Health Place. 2016;40:123-128. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim A, Loomis B, Rhodes B, Eggers ME, Liedtke C, Porter L. Identifying e-cigarette vape stores: description of an online search methodology. Tob Control. 2016;25:e19-23. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Colditz JB, Chu K, Switzer GE, Pelechrinis K, Primack BA. Online data to contextualize waterpipe tobacco smoking establishments surrounding large US universities. Health Informatics J. 2019;25:1314-1324. doi: 10.1177/1460458217754242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yelp. Support center. https://www.yelp-support.com/. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 29. Yelp. Fast facts. https://www.yelp-press.com/company/fast-facts/default.aspx. Published 2019. Accessed March 24, 2020.

- 30. Giovenco DP. Smoke shop misclassification may cloud studies on vape shop density. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20:1025-1026. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. PA Department of Revenue. Tobacco products tax licenses current revenue. opendataPA. https://data.pa.gov/Licenses-Certificates/Tobacco-Products-Tax-Licenses-Current-Revenue/ut72-sft8. Published 2018. Accessed December 5, 2019.

- 32. Python Software Foundation. “difflib”—Helpers for computing deltas. Python, Documentation, The Python Standard Library, Text Processing Services; https://docs.python.org/3.6/library/difflib.html. Published 2018. Accessed March 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dai H, Hao J. Geographic density and proximity of vape shops to colleges in the USA. Tob Control. 2017;26:379-385. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chu K, Colditz JB, Primack BA, et al. JUUL: spreading online and offline. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:582-586. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. King BB, Gammon DG, Marynak KL, Rogers T. Electronic cigarette sales in the United States, 2013-2017. JAMA. 2018;320:1379-1380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28:146-151. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee YO, Kim AE. “Vape shops” and “e-cigarette lounges” open across the USA to promote ENDS. Tob Control. 2015;24:410-412. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kong G, Unger J, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Sussman S. The associations between yelp online reviews and vape shops closing or remaining open one year later. Tob Prev Cessat. 2017;2:9. doi: 10.18332/tpc/67967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martin MR, Ortega K, Reine T, et al. Health Impacts and Taxation of Electronic Cigarettes. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana Department of Revenue; 2018. http://ldh.la.gov/assets/docs/LegisReports/HR155RS2017ecigarettes12018.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pennsylvania PennWATCH. Revenue Source by Fiscal Year. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania PennWATCH; 2020. http://pennwatch.pa.gov/revenue/Pages/Revenue-Source-by-Fiscal-Year.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jubelirer RC. East Coast Vapor, LLC v. PA Department of Revenue, Eileen H. McNulty, Secretary of Revenue in Her Official and Individual Capacity, 48 M.D. 2017 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2018). https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/4510012/east-coast-vapor-llc-v-pa-department-of-revenue-eileen-h-mcnulty/. Published June 22, 2018.

- 42. Hoffman BL, Tulikangas MC, James AE, et al. Pennsylvania policymakers’ knowledge, attitudes and likelihood for action regarding waterpipe tobacco smoking and electronic nicotine delivery systems. Tob Prev Cessat. 2018;4:14. doi: 10.18332/tpc/89624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]