Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to explore clinicians’ perspectives on the current practice of perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) management and strategies to improve future implementation.

Methods:

This study had a cross-sectional, descriptive design. A 35-item electronic survey was sent to clinicians (N = 118) who treated perinatal women and practiced at several community clinics at an academic medical center in the United States.

Results:

Among clinicians who provided care for perinatal women, 34.7% reported never receiving PMAD management training and 66.3% had less than 10 years of experience. Out of 10 patients who reported psychiatric symptoms, 47.8% of clinicians on average reported providing PMAD management to 1 to 3 patients and 40.7% noted that they conducted screening only when patient expresses PMAD symptoms. Suggested future improvements were providing training, developing a referral list, and establishing integrated behavioral health services.

Conclusions:

Results from this study indicated that while PMAD screening and management was implemented, improvements are warranted to meet established guidelines. Additionally, clinicians endorsed providing PMAD management to a small percentage of perinatal patients. Suggested strategies to increase adoption and implementation of PMAD management should be explored to improve access to behavioral health services for perinatal women.

Keywords: perinatal depression and anxiety, screening, behavioral health

Introduction

Depression is prevalent in 10% to 20% of women during the perinatal period.1 Depressive symptoms have been shown to emerge prior to pregnancy (26.5%), during pregnancy (33.4%), and 4 to 6 weeks after birth (40.1%).2 Anxiety is also highly comorbid with depression in this population3,4 with estimates of prevalence ranging widely from 2.6% to 39% of women reporting anxiety symptoms during5,6 and after pregnancy.7,8

Dire consequences of untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders (PMAD) have been described; for example, maternal suicide remains a leading cause of death in the postpartum period.9,10 Maternal psychiatric illness has been shown to increase risk for placental pathology, fetal growth issues, preterm delivery, disordered attachment, and adverse developmental outcomes.11-13 Additional negative childhood outcomes associated with maternal mental illness include emotional and behavioral difficulties, low levels of cognitive development, and poor physical and growth development.14

PMAD management is defined as the provision of behavioral health assessment and intervention (eg, pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy) to perinatal women. Current recommendations for PMAD management include screening for symptoms at least once during the perinatal period, using validated screening measures, increasing frequency of visits when elevated symptoms are identified, and referring patients to appropriate pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy resources.15-17 These recommendations align with existing guidelines from the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on antenatal and postnatal mental health18 as well as American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.19

Despite PMAD management guidelines, there is a gap between these recommendations and the practice of caring for women living with PMAD.20 A systematic review found that only 55% of physicians routinely screen for PMAD.21 Appropriate, timely screening is necessary to capture all patients with PMAD symptoms.22 When PMAD symptoms are elevated, clinicians reported feeling ill-equipped to initiate further intervention, provided referrals, or both.23 Although pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy have been shown to be beneficial for women with PMAD,24,25 less than 25% of affected women receive behavioral health services tailored to PMAD.26,27 Moreover, while the majority of women preferred psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy,28 current estimates show that 75% of pregnant women with depression are referred for pharmacotherapy only.29

Barriers to providing PMAD management occur at different levels. Women have reported difficulty disclosing emotional distress, a desire to handle PMAD on their own, and limited knowledge of PMAD as factors that reduce their willingness to participate in treatment.30,31 Limited insurance coverage is an additional barrier to perinatal women’s participation in behavioral health services.32 Moreover, many clinicians perceive PMAD screening as difficult to carry out in everyday practice and question whether screening improves outcomes.33 One study found that only 15% of positively screened mothers had evidence of mental health treatment in their medical record during pregnancy, with equally low rates of referral to behavioral health or social services. In the postpartum period, 25% of positively screened mothers received treatment, and only 2.5% were referred.34

The aims of this study were to characterize clinicians’ PMAD management training, experiences, current practices, and suggested strategies for PMAD management implementation. The present study was part of a larger quality improvement project seeking to advance the delivery of PMAD management across multicenter community practices.

Methods

This study utilized a cross-sectional, descriptive design, using an online questionnaire. This study was conducted at a not-for-profit academic medical center in the United States with multiple sites across four states. Practices across the state of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Florida, where branches of the medical center were located, were included in the study. Clinicians practiced in diverse settings including Family Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Social Work.

The purpose of the questionnaire was to characterize clinicians’ PMAD management training, past experiences, current practices, and perceived strategies that might improve the adoption and implementation of improved PMAD management. Initial questions were generated and reviewed by the research team. We went through three iterations of the questionnaire. Suggested changes included adding and removing certain questions and improving grammatical errors and wordings. Our research team members took the survey draft to assure readability after each iteration. Thirty five questions were included in the questionnaire. Main sections of the questionnaire included: (1) demographics and current field of practice; (2) past training and clinical experiences in PMAD management; (3) perceived comfort to manage psychiatric diagnoses for perinatal women; and (4) recommended strategies to support future PMAD management implementation.

Clinicians practicing in the institution, who reported providing care to pregnant and/or post-partum (ie, 1 year after delivery) women, were recruited via email and provided a link to the electronic survey. Two weeks after the first invitation, a second invitation email was sent to clinicians who had not completed the survey. Clinicians completed the 10-minute questionnaire via REDcap, an online portal approved by the institution to distribute survey research.

The study protocol was approved by the institution Institutional Review Board (IRB #18-011824). Participation was voluntary and clinicians indicated their consent to participate on the virtual survey. Once the questionnaire was submitted, data was automatically encrypted and transmitted to a secure database on a server hosted within the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology. All data were treated as private and confidential. No participants indicated a wish to withdraw from the study. Descriptive statistics were generated to identify the most commonly endorsed items. Content analysis was used on the open-ended questions to identify themes in the data.

Results

The email invitation was sent to 443 clinicians. A total of 201 providers responded to the survey (45% participation rate). Fifty nine clinicians identified that they did not provide care to perinatal women and 24 clinicians opened the questionnaire but did not complete it. Thus, data from 118 clinicians were included in the final analysis (27% participation rate for completed response).

The final sample included clinicians from Minnesota and Wisconsin sites. None of the clinicians from Florida and Arizona sites responded to the survey. Clinicians came from several disciplines: Family Medicine (N = 42), Obstetrics and Gynecology (N = 35), Pediatrics (N = 1), and Social Work (N = 40). The majority (N = 92; 78%) of clinicians were women with mean age of 42.8 (SD = 9.99). Table 1 presents further demographic variables.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Practice site | ||

| Mayo Clinic Rochester | 81 | 68.6 |

| Mayo Clinic Health System (Wisconsin and Minnesota sites) | 37 | 31.4 |

| Discipline | ||

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 35 | 29.7 |

| Family medicine | 42 | 35.6 |

| Pediatrics | 1 | 0.8 |

| Social work | 40 | 33.9 |

| Current position | ||

| Midwife | 15 | 12.7 |

| Physician | 44 | 37.3 |

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistant | 16 | 13.6 |

| Social work | 40 | 33.9 |

| Other | 3 | 2.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 92 | 77.8 |

| Male | 25 | 21.2 |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.8 |

| Age | M = 42.8; SD = 9.99 | |

| Ethnicity (mark all that apply) | ||

| Caucasian/White (Non-Hispanic) | 102 | 86.4 |

| Black/African-American | 3 | 2.5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2 | 1.7 |

| Hispanic/Latin-American | 3 | 2.5 |

| Mixed | 1 | 0.8 |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 | 5.1 |

| Highest education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 | 0.8 |

| Master’s degree | 71 | 60.2 |

| Doctoral degree or equivalent | 4 | 3.4 |

| Medical degree | 41 | 34.7 |

| Other | 1 | 0.8 |

| Licensure status | ||

| Currently licensed | 118 | 100.0 |

| How many years of experiences do you in in PMAD management? | ||

| Less than 1 year | 15 | 12.9 |

| 1-5 years | 36 | 31.0 |

| 5-10 years | 26 | 22.4 |

| 10-20 years | 25 | 21.6 |

| More than 20 years | 14 | 12.1 |

| What training/experiences have you already had with PMAD management? | ||

| I received formal training on PMAD management | 49 | 41.5 |

| I have attended a workshop on PMAD management | 25 | 21.2 |

| I have been supervised in providing PMAD management | 31 | 26.2 |

| I never received any training on PMAD management | 41 | 34.7 |

| How knowledgeable are you with PMAD management? | ||

| Not at all knowledgeable | 7 | 5.9 |

| Somewhat knowledgeable | 58 | 49.2 |

| Moderately knowledgeable | 40 | 33.9 |

| Very knowledgeable | 13 | 11.0 |

| How comfortable are you in managing PMAD? | ||

| Not at all comfortable | 14 | 11.9 |

| Somewhat comfortable | 46 | 39.0 |

| Moderately comfortable | 42 | 35.6 |

| Very comfortable | 16 | 13.6 |

PMAD Management Training, Experiences, and Perceived Comfort

Table 1 describes clinicians’ past training and experience providing PMAD management. The majority of clinicians reported that they had received formal training, attended a workshop, or received supervision on PMAD management. A portion of the clinicians (34.7%) noted that they had never received any PMAD management training in the past. Clinicians reported that they were somewhat knowledgeable (49.2%) or moderately knowledgeable (33.9%) on PMAD management. A smaller percentage indicated that they were very knowledgeable (11%) or not at all knowledgeable (5.9%). In terms of past experiences in providing PMAD management, 66.3% reported having less than 10 years of experience.

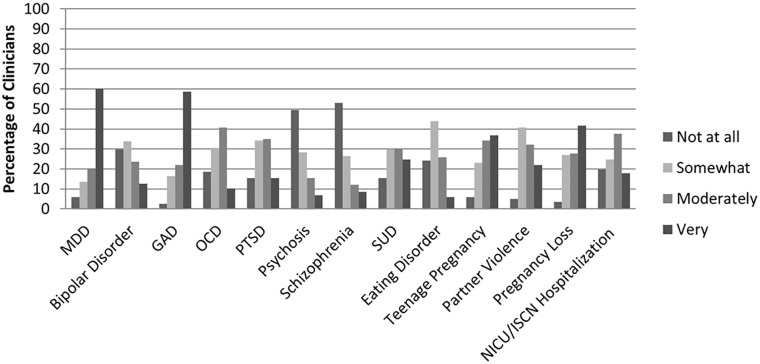

With regard to perceived comfort, clinicians reported being somewhat comfortable (39%) or moderately comfortable (35.6%) providing PMAD management while a smaller percentage reported being very comfortable (13.6%) or not at all comfortable (5.9%). Figure 1 summarizes perceived comfort to assess and treat different psychiatric conditions. Clinicians reported feeling most comfortable treating generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, and pregnancy loss. Respondents felt least comfortable treating eating disorders, psychosis, and schizophrenia among the perinatal population.

Figure 1.

Perceived comfort to treat psychiatric and other conditions.

Current Practice of PMAD Management

Table 2 describes current PMAD management practices. We asked, “Out of 10 patients with PMAD, to how many women do you provide PMAD management?” Among respondents, 47.8% reported that they provided PMAD management to 1 to 3 patients, 20% to 4 to 6 patients, 21.7% to 7 to 9 patients, and 10.4% to all 10 patients. When asked, “to what extent do you manage PMAD in your clinical practice?” most clinicians provided some PMAD management with 7.6% noted that they did not provide any PMAD management.

Table 2.

Current Practice of PMAD Management.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| To what extent do you manage PMAD in your current clinical practice? | ||

| Not at all | 9 | 7.6 |

| A little | 47 | 39.8 |

| A moderate amount | 31 | 26.3 |

| A lot | 12 | 10.2 |

| I provide PMAD management to every patient with elevated depression and anxiety | 19 | 16.1 |

| Out of 10 patients you see with psychiatric/psychological concerns, for how many would you expect to provide PMAD management? | ||

| 1-3 | 55 | 47.8 |

| 4-6 | 23 | 20.0 |

| 7-9 | 25 | 21.7 |

| All 10 | 12 | 10.4 |

| Do you use any patient standardized self-report measures to assess for depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric/psychological symptoms? (Mark all that apply) | ||

| We do not screen for psychiatric/psychological symptoms | 3 | 2.5 |

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | 49 | 41.5 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items (PHQ-9) | 89 | 75.4 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire – 2 items (PHQ-2) | 13 | 11.0 |

| Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) | 19 | 16.1 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 items (GAD-7) | 75 | 63.6 |

| PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCLC) | 2 | 1.7 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) | 31 | 26.3 |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) | 3 | 2.5 |

| Other | 12 | 10.2 |

| How often do you administer the standardized self-report measures? (Mark all that apply) | ||

| When patient expresses PMAD symptoms | 48 | 40.7 |

| Initial visit only | 15 | 12.7 |

| Once each trimester | 11 | 9.3 |

| Once between initial visit and postpartum | 18 | 15.3 |

| Postpartum only | 28 | 23.7 |

| All prenatal visits | 6 | 5.1 |

| All prenatal and postnatal visits | 7 | 5.9 |

| After pregnancy loss | 17 | 14.4 |

| Intend to screen, but it is not always completed | 9 | 7.6 |

| Other | 31 | 26.3 |

| What are the barriers to use standardized self-report measures to assess for psychiatric/psychological symptoms? (Mark all that apply) | ||

| No time | 27 | 22.9 |

| No reimbursement | 3 | 2.5 |

| Low number of patients with psychiatric/psychological concerns | 6 | 5.1 |

| No resources to refer patients with psychiatric/psychological concerns | 20 | 16.9 |

| Do not feel comfortable to assess | 3 | 2.5 |

| Do not have adequate training | 10 | 8.5 |

| Patients do not like us to ask questions related to psychiatric/psychological concerns | 5 | 4.2 |

| Our practice do not have adequate resources to implement self-report measures (eg, lack of staffing, lack of electronic health records) | 9 | 7.6 |

| Other | 29 | 24.6 |

| What steps do you take when patients reported elevated psychiatric/psychological symptoms? (Mark all that apply) | ||

| I provide further evaluation | 95 | 80.5 |

| I provide further treatment | 78 | 66.1 |

| Refer to my own services | 24 | 20.3 |

| Refer to mental health clinic/agency | 79 | 66.9 |

| Refer to individual mental health provider | 66 | 55.9 |

| Refer to hospital social worker | 36 | 30.5 |

| Refer to other type of provider | 33 | 28.0 |

| I do not know what further services are available | 0 | 0 |

| Other steps taken | 9 | 7.6 |

We assessed the degree to which clinicians conduct mental health screening in their practice. We asked, “How often do you administer standardized self-report measures?” The top three selected time points were when patient expresses PMAD symptoms (40.7%), other (26.3%), and postpartum only (23.7%). The three least selected time points were all prenatal visits (5.1%), all prenatal and postnatal visits (5.9%), and intend to screen but it is not always completed (7.6%). The top three most commonly used patient reported outcome (PRO) measures were Patient Health Questionnaire 9-items35 (PHQ-9; 75.4%), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-items36 (GAD-7; 63.6%), and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale37 (EPDS; 41.5%).

Barriers to screening for psychiatric symptoms were assessed and the top three reported barriers were unspecified barriers (24.6%), lack of time (22.9%), and no resources to refer patients with psychiatric concerns (16.9%). Since “other” was the most commonly endorsed, qualitative response was further analyzed. Table 3 presents other barriers reported by providers, which include problems with the selection of PRO measures, institutional barriers, limited resources to support PRO measures implementation and PMAD management, patient-level barriers, provider/staff level barriers, and lack of training.

Table 3.

Qualitative Report of Barriers to Implement PMAD Screening.

| Problems with the selection of PRO measures |

|---|

| • Barrier is not having an identified screening tool that is evidenced based |

| • I desire to use the Edinburgh scale but Mayo is resistant |

| • Mayo wanting a universal tool and universal practice/implementation |

| Institutional barriers |

| • I desire to use the Edinburgh scale but my institution is resistant |

| • Mayo wanting a universal tool and universal practice/implementation |

| • System is unclear and I am not in clinic enough |

| • Social work being utilized only when dismissal planning is needed |

| • We have not successfully integrated routine prenatal screenings into our practice |

| Limited resources to support PRO measures implementation |

| • Limited resources to manage psychiatric |

| • Minimal resources with quick timeline to evaluate/treat in behavioral health |

| • Resources not available in timely manner |

| • Limited resources for follow up care |

| • Once behavioral health needs are identified given time constraints for the pregnant woman, it is difficult to motivate the woman to engage in behavioral health services that often are difficult to access(limited qualified providers) |

| • When I screen at increase frequency I am seen as demanding more of nursing staff since “all the other providers are not doing it” also we cannot even refer internal patients to psychiatrist right now |

| Patient-level barriers |

| • Patient does not always complete |

| • Some patients choose not to complete |

| • Sometimes patient does not want to complete |

| • Once behavioral health needs are identified given time constraints for the pregnant woman, it is difficult to motivate the woman to engage in behavioral health services that often are difficult to access(limited qualified providers) |

| • Language barriers |

| • Patients are sick from medication and radiation so the test is not valid |

| Provider/staff-level barriers |

| • Sometimes the CA forgets to give the screen test. No barriers otherwise to screening outside of human error |

| • Already done by admission nurse |

| • Nurses not trained to hand out screening at specified intervals |

| • Lack of education and therefore consistency in screening through support staff |

| • Desk staff don’t always provide the tools on check in |

| • No standardized rooming procedure |

| • Staff not always consistent in giving the screen |

| • When I screen at increase frequency I am seen as demanding more of nursing staff since “all the other providers are not doing it” also we cannot even refer internal patients to psychiatrist right now |

| • Competing priorities; everyone has their favorite, evidence-based screen or test that needs to be done in 15 minutes |

| • I prefer to assess and have a conversation |

| • Work in domestic violence, not always applicable |

| Lack of training |

| • Nurses not trained to hand out screening at specified intervals |

| • Lack of education and therefore consistency in screening through support staff |

| • Knowing meds safe for pregnancy and breast feeding |

We further assessed the next steps that clinicians took when patients reported elevated psychiatric or psychological symptoms. The top three selected options were, “I provide further evaluation” (80.5%), “refer to mental health clinic/agency” (66.9%), and “I provide further treatment” (66.1%).

Suggested Strategies to Improve Future PMAD Management

Clinicians rated factors that may promote successful implementation of PMAD management in their clinical practice (Table 4). The top three facilitators were receiving PMAD management training (77.1%), receiving referral list of behavioral health services in the area (67.8%), and having co-located behavioral health clinicians in their clinic (67.8%). Furthermore, clinicians were asked to rate topics to include in future PMAD management training that would be relevant to their practice. The top three training topics of interest were PMAD treatment (69.5%), resources and referrals (66.9%), and screening for psychiatric diagnosis (50%).

Table 4.

Suggested Strategies to Improve Future PMAD Management.

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| What resources do you think will facilitate successful PMAD management in your clinical practice? (mark all that apply) | ||

| Training on PMAD management | 91 | 77.1 |

| Referral list for external mental health providers | 80 | 67.8 |

| Co-located or integrated mental health providers | 80 | 67.8 |

| A clinical pathway to guide decision making when patients reported elevated psychiatric/psychological symptoms | 62 | 52.5 |

| Patient education materials (eg, pamphlets, brochures) | 66 | 55.9 |

| Staff support to give measures to patients prior to clinical appointment | 41 | 34.7 |

| Electronic administration of self-reported measures (eg, using tablet or computer) | 33 | 28.0 |

| Ease of accessing screening results | 23 | 19.5 |

| If you are interested in receiving further training in PMAD management, what topics would you like to learn more about? (mark all that apply) | ||

| Screening for psychiatric/psychological symptoms | 59 | 50.0 |

| PMAD treatment | 82 | 69.5 |

| Resources/referrals | 79 | 66.9 |

| I am not interested in receiving PMAD management training | 5 | 4.2 |

| Other | 5 | 4.2 |

Discussion

The present study explored clinician perspectives on PMAD training, assessment, and management and suggests strategies to improve future practice. We support and extend research on PMAD management by integrating clinician perspectives across clinical practices where perinatal women receive health services (eg, family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and social work). Findings from this study demonstrate deficiencies in PMAD training and experience among clinicians involved in perinatal care. While some clinicians reported receiving a formal training on PMAD management (41.5%) and had PMAD management supervision (26.2%), the rest indicated that they never received training on PMAD management (34.7%) or only attended one workshop in the past (21.2%). This suggests that more than half of clinicians who provide perinatal care may benefit from receiving further training and supervision on the management of PMAD.

These findings echo previous reports that clinicians lack access to training and resources specific to the management of perinatal mental health concerns.38-40 The importance of providing training and supervision specific to the management of PMAD is beginning to receive more attention and has been identified as a critical step toward improving access to comprehensive care for this patient population.41 Past studies have noted that many women perceived their clinicians to be inadequate in this area,42,43 highlighting the importance of implementing routine training in the assessment and treatment of PMAD for improving clinical outcomes.44

A notable subset of clinicians (40.7%) reported utilizing standardized PRO measures only when patients expressed PMAD symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous studies describing heterogeneous, and in some cases nonexistent, screening for PMAD symptoms.21 These trends suggest that many women in need of behavioral health services are not assessed and possibly do not receive adequate treatment. Additionally, only a small percentage of providers reported administering PRO measures at all prenatal visits (5.1%) which departs from current guidelines recommending that perinatal women with elevated psychiatric and psychological symptoms be assessed more frequently.19

Our findings support the argument for the increased use of validated measures given that, in the absence of systematic screening, most women with elevated depression and anxiety symptoms are not adequately detected by clinicians.45 An essential next step in the management of PMAD will be to implement systematic screening practices to ensure that perinatal women living with PMAD are identified and connected to adequate care. Moreover, out of 10 perinatal women who expressed PMAD symptoms, about half of the clinicians (47.8%) reported only providing PMAD management to 1-3 women. This could yield several interpretations. First, these clinicians might provide referrals to external behavioral health services for the majority of their patients with PMAD symptoms since 66.9% of them noted that they “refer patients to mental health clinic/agency.” Though, it is also possible that most women do not receive adequate treatment or referral, given that current evidence indicates that less than 25% of women with PMAD receive behavioral health services.26,27 Future studies should explore the extent to which women with PMAD symptoms receive behavioral health services and the barriers to adequate treatment or referral to external services.

Clinicians across specialties reported a desire to receive additional training in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of PMAD. They also expressed interest in improving coordination and follow-up of PMAD care through the use of referral lists detailing multidisciplinary services and local providers with PMAD treatment experience. Integrated behavioral health service were also highlighted as a key systems-level change that would meaningfully reduce barriers to PMAD treatment.

There are a number of limitations that may restrict generalizability of this study. First, the sample was comprised of clinicians from one academic health center. Furthermore, no clinicians from the health system’s Arizona and Florida sites responded to the survey invitation. This limits the generalizability of findings to institutions with differing organizational structures, climates, and resources. Furthermore, our response rate was lower than average at 45% for those who started the survey and 27% for those who completed the survey.46 Strategies to improve survey completion should be considered, which may include engaging leadership and institutional support to encourage research participation, providing incentive for completing the questionnaire, and extending data collection time frame to allow for additional reminders for survey completion.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the current state of PMAD training, assessment, and management. While many clinicians reported having adequate training, experiences, and endorsed providing some PMAD management to perinatal women, half of the participating clinicians could benefit from receiving further training and resources to support perinatal women with PMAD. Findings indicate the need to provide adequate resources such as referral lists and co-located behavioral health clinicians in practices where women with PMAD seek care. Our study sets the stage for additional research on the implementation strategies needed to effectively advance current PMAD management practices.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors whose names are listed in this manuscript certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ajeng J. Puspitasari  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8552-7498

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8552-7498

Jason S. O’Grady  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0541-7265

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0541-7265

Emily K. Johnson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5897-4869

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5897-4869

Ethical Approval Statement: This research was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and written consent was exempt and not obtained from participants.

References

- 1. Babb JA, Deligiannidis KM, Murgatroyd CA, Nephew BC. Peripartum depression and anxiety as an integrative cross domain target for psychiatric preventative measures. Behav Brain Res. 2015;276:32-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:490-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bentley SM, Melville JL, Berry BD, Katon WJ. Implementing a clinical and research registry in obstetrics: overcoming the barriers. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:192-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Connell T, Barnett B, Waters D. Barriers to antenatal psychosocial assessment and depression screening in private hospital settings. Women Birth. 2018;31:292-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goodman JH, Chenausky KL, Freeman MP. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e1153-e1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leach LS, Poyser C, Fairweather-Schmidt K. Maternal perinatal anxiety: a review of prevalence and correlates. Clin Psychol. 2017;21:4-19. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glasheen C, Richardson GA, Fabio A. A systematic review of the effects of postnatal maternal anxiety on children. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13:61-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goodman JH, Watson GR, Stubbs B. Anxiety disorders in postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:292-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, et al. Consensus bundle on maternal mental health: perinatal depression and anxiety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:272-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuhr DC, Calvert C, Ronsmans C, et al. Contribution of suicide and injuries to pregnancy-related mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:213-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vameghi R, Akbari SAA, Sajjadi H, Sajedi F, Alavimajd H. Correlation between mothers’ depression and developmental delay in infants aged 6-18 months. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martins C, Gaffan EA. Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant–mother attachment: A meta-analytic investigation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:737-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jablensky AV, Morgan V, Zubrick SR, Bower C, Yellachich L-A. Pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal complications in a population cohort of women with schizophrenia and major affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:79-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014; 384:1800-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Practice ACoO. ACOG Committee opinion no. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208-e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matthey S. Detection and treatment of postnatal depression (perinatal depression or anxiety). Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2004;17:21-29. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knights JE, Salvatore ML, Simpkins G, Hunter K, Khandelwal M. In search of best practice for postpartum depression screening: is once enough? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;206:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howard LM, Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, Pilling S. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g7394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ACOG. ACOG committee opinion no. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e208-e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu M, Sampson M. Closing the gap between policy and practice in screening for perinatal depression: a policy analysis and call for action. Soc Work Public Health. 2016;31: 549-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evans MG, Phillippi S, Gee RE. Examining the screening practices of physicians for postpartum depression: implications for improving health outcomes. Womens Health Issues. 2015;25:703-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:388-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ACOG. Committee opinion no. 453: screening for depression during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115: 394-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP. A meta-analysis of treatments for perinatal depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:839-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Misri S, Kendrick K. Treatment of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:489-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bina R. Seeking help for postpartum depression in the Israeli Jewish Orthodox Community: factors associated with use of professional and informal help. Women Health. 2014;54:455-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McIntosh J. Postpartum depression: women’s help-seeking behaviour and perceptions of cause. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18: 178-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Battle CL, Salisbury AL, Schofield CA, Ortiz-Hernandez S. Perinatal antidepressant use: understanding women’s preferences and concerns. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19:443-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Hornbrook MC. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1515-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33:323-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kingston D, Austin M-P, Heaman M, et al. Barriers and facilitators of mental health screening in pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:350-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sobey WS. Barriers to postpartum depression prevention and treatment: a policy analysis. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2002;47:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. LaRocco-Cockburn A, Melville J, Bell M, Katon W. Depression screening attitudes and practices among obstetrician–gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:892-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health. 2010;19:477-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32: 509-515. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rothera I, Oates M. Managing perinatal mental health: a survey of practitioners’ views. Br J Midwifery. 2011;19:304-313. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noonan M, Galvin R, Jomeen J, Doody O. Public health nurses’ perinatal mental health training needs: a cross sectional survey. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:2535-2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bayrampour H, Hapsari AP, Pavlovic J. Barriers to addressing perinatal mental health issues in midwifery settings. Midwifery. 2018;59:47-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gjerdingen DK, Yawn BP. Postpartum depression screening: importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:280-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bennett IM, Palmer S, Marcus S, et al. “One end has nothing to do with the other:” patient attitudes regarding help seeking intention for depression in gynecologic and obstetric settings. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Byatt N, Biebel K, Friedman L, Debordes-Jackson G, Ziedonis D, Pbert L. Patient’s views on depression care in obstetric settings: how do they compare to the views of perinatal health care professionals? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:598-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Avalos LA, Raine-Bennett T, Chen H, Adams AS, Flanagan T. Improved perinatal depression screening, treatment, and outcomes with a universal obstetric program. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delatte R, Cao H, Meltzer-Brody S, Menard MK. Universal screening for postpartum depression: an inquiry into provider attitudes and practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200: e63-e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cummings SM, Savitz LA, Konrad TR. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1347-1355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]