Abstract

Latinx adults, especially immigrants, face higher uninsurance and lower awareness of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) provisions and resources compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Television advertising of ACA health plans has directed many consumers to application assistance and enrollment, but little is known about how ads targeted Latinx consumers. We used Kantar Media/CMAG data from the Wesleyan Media Project to assess Spanish- vs. English-language ad targeting strategies and to assess which enrollment assistance resources (in person/telephone vs. online) were emphasized across three Open Enrollment Periods (OEP) (2013-14, 2014-15, 2015-16). We examined differences in advertisement sponsorship and volume of Spanish- versus English-language ads across the three OEPs. State-based Marketplaces sponsored 47% of Spanish-language airings; insurance companies sponsored 55% of English-language airings. The proportion of Spanish-language airings increased over time (8.8% in OEP1, 11.1% in OEP2, 12.0% in OEP3, p<.001). Spanish-language airings had 49% lower (95%CI: 0.50,0.53) and 2.20 times higher odds (95%CI: 2.17,2.24) of mentioning online and telephone/in-person enrollment assistance resources, respectively. While there was a significant decrease in mention of telephone/in-person assistance over time for English-language airings, these mentions increased significantly in Spanish-language airings. Future research should examine the impact of the drastic federal cuts to ACA outreach and marketing.

Keywords: health insurance advertising, Affordable Care Act, Latinx, immigrants, health insurance outreach and enrollment

INTRODUCTION

Television advertising of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) health insurance Marketplace has been an important component of outreach since enrollment began in 2013. Research has linked the millions of ads aired with consumers’ use of enrollment resources and with plan enrollment (Gollust et al., 2018; Karaca-Mandic et al., 2017; Shafer, Fowler, Baum, & Gollust, 2018). Counties with higher ad volume saw a significantly higher uptake in coverage (Karaca-Mandic et al., 2017) and higher ad volumes aired were related to higher odds of individuals’ reporting of “shopping” for Marketplace plans (Gollust et al., 2018). Prior research also found that Spanish and English ads differed in their key messages (Barry et al., 2018). Spanish-language ads were more likely than English-language ads to mention that enrollment assistance was available, but less likely to emphasize simplicity of enrollment (Barry et al., 2018).

Latinx adults, especially immigrant and Spanish-speaking adults, faced the highest rates of uninsurance pre-ACA (Artiga, 2013; Bustamante, Fang, Rizzo, & Ortega, 2009; Rodriguez, Bustamante, & Ang, 2009). Despite substantial gains, they are still the most likely to be uninsured post-ACA (Chen, Vargas-Bustamante, Mortensen, & Ortega, 2016). Thus, it is important to understand how these ads were targeted to Spanish-speaking communities and what enrollment resources were emphasized. Latinx adults have been among the least aware of key ACA provisions (Garcia Mosqueira, Hua, & Sommers, 2015; Ghaddar, Byun, & Krishnaswami, 2018; Hernandez-Cancio & Rivera, 2014; Sanchez, 2015), such as availability of financial subsidies (Coe, Cordina, Jones, & Rivera, 2015). One study reported that under half of potentially eligible Latinx adults were aware of the Marketplaces and coverage options available, compared to 60% and 80% of black and white adults, respectively (Doty, Gunja, Collins, & Beutel, 2016). Lack of knowledge of the ACA’s provisions among Latinx adults has been linked to lower confidence in choosing a plan (Ghaddar et al., 2018). A California-specific survey showed that language was the greatest factor in being aware of Marketplace TV ads and understanding ACA options, and Spanish speakers were twice as likely to report not knowing how to apply as the main reason for not enrolling (Bye, 2014). Not all Latinxs speak Spanish or watch Spanish-language media, but 74% of Latinx adults speak Spanish (36% speak both English and Spanish and 38% speak mainly Spanish); among those who speak English, 59% are bilingual (Krogstad & Gonzalez-Barrera, 2015). Moreover, Spanish-language TV viewing is much more common than English-language TV in Spanish-speaking (solely or bilingual) households (Pardo & Dreas, 2011).

Telephone and in-person enrollment assistance are crucial pathways to coverage for Latinx adults. Studies found that Latinx adults were more likely than other groups to have received in-person ACA enrollment assistance (Garcia Mosqueira et al., 2015); those who did were more likely to enroll (Garcia Mosqueira & Sommers, 2016). Spanish speakers have also been more likely than English-language speakers to seek out telephone or in-person assistance compared to online information (Bye, 2014). Latinx-serving organizations have identified lack of awareness and information about eligibility and enrollment assistance as some of the greatest enrollment barriers (McDonough et al., 2014). Release of Spanish-language marketing materials was delayed during the beginning of Open Enrollment Period 1 (OEP1) (Hernandez-Cancio & Rivera, 2014) in late 2013/early 2014, and Latinx adults were much more likely to report having had technical problems with online Marketplace platforms (Coe et al., 2015), meaning awareness of in-person or telephone assistance would have been even more critical during that time.

Examining whether ads provided explicit information about in-person or telephone enrollment assistance versus online resources is crucial to understanding what the most effective strategies may be to facilitate enrollment for Latinxs. Since the ACA was implemented unevenly across states, the availability of information about enrollment resources varies (Gollust, Barry, Niederdeppe, Baum, & Fowler, 2014; Gollust et al., 2018). States with their own Marketplace would have had dedicated funding for ads, while states relying on the federal Marketplace would only be exposed to federal ads. However, insurance companies may have made up for this gap in states without their own Marketplaces. Thus, it is important to understand differences in resources provided in ads based on sponsorship of ads, especially in light of ongoing declines in federal investment in marketing since 2017 (Ollstein, 2017).

Because television advertising was a significant component of ACA outreach, the extent to which Latinx communities were exposed to ads – and the content of these ads – likely influenced their understanding and knowledge of the law, as well as their ability to access resources to learn about and enroll in coverage. In this study, we compare rates of mentioning telephone/in-person enrollment assistance resources and online resources among Spanish-language relative to English-language ads over three OEPs (2013-14, 2014-15, 2015-16). We also examine differences in advertisement sponsorship and volume of Spanish- versus English-language ads across this timeframe. We analyzed temporal differences in light of increased federal investment in Hispanic media between 2014-2015 and increased enrollment assistance for Latinxs in the 2015 round of navigator grants, following criticism that uninsured Latinxs were overlooked in OEP1. With demographic shifts due to immigration (Zong, Batalova, & Burrows, 2019) and the potential to address insurance inequities among Latinx populations and diversify insurance pools (Ortega, Rodriguez, & Vargas Bustamante, 2015), it is important to understand the volume and content of Spanish-language ads. While this study does not encompass changes to enrollment outreach and marketing funding implemented since the Trump administration began, the findings can inform continuing efforts to engage remaining uninsured Latinxs, particularly for states, enrollment advocates, and navigators.

METHODS

Data

Our sample of television health insurance product advertising data originated from Kantar Media’s Campaign Media Analysis Group (CMAG) through the Wesleyan Media Project and encompassed ads airing across ACA OEP1-3 (OEP1: 2013-14, OEP2: 2014-15, OEP3: 2015-16). Kantar Media tracks 936 (primarily) English-language television stations across all 210 designated market areas (DMA) – geographic areas that receive the same local television programming – and 108 Spanish-language television stations across 38 DMAs. The methods used to access these ads are described in Barry et al.4 A total of 3,747 unique ads broadcast on local TV or national cable stations were captured by Kantar Media/CMAG. Ads airing solely on national cable were excluded from our analysis since they do not vary by local geography. Seventy-three percent of unique ads and 89% of airings were ultimately included in the sample frame. We classified ads by DMA and OEP; we also collected data on the volume of airings by DMA and OEP. We randomly sampled 1,054 unique ads for our content analysis. Ads marketing Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and hospitals/health systems (N=167) were excluded, given our focus on health insurance for nonelderly adults. A total of 875 ads were included in our final sample. Spanish-language ads made up 15% of the sample. The volume of airings varied from 490,659 (including 43,074 Spanish-language) in OEP1 to 337,068 (37,338 Spanish) in OEP2 to 246,926 (29,722 Spanish) in OEP3.

Coding and Measures

Three authors (SB, KTA, JKP) coded audio and visual content of Spanish- and English-language ads. To assess item interrater reliability, two authors double-coded a random sample (12%) of English-language ads; a single author (JKP) coded all Spanish-language ads but was engaged in comprehensive training on the instrument alongside the other two coders to assure coding reliability. In addition, after coding select ads individually during the pilot phase, all three coders met several times to debrief, compare individual coding, and discuss any discrepancies in order to ensure reliability in coding. For the current analysis, we measured whether each unique ad provided a phone number or in-person (e.g., enrollment center, health fair) assistance enrollment resources (Kappa of double-coded English-language sample: 0.88, raw percent agreement: 94%) and/or website/online enrollment resources (Kappa of double-coded English-language sample: 0.65; raw percent agreement: 94%). We classified ads by sponsor, including insurance company, state-based ACA Marketplace, federal ACA marketplace, or an enrollment advocate organization (e.g., Enroll America) (Kappa of double-coded English-language sample: 0.87; raw percent agreement: 94%). Covariates included three DMA-level measures based on 2012 data: percent Latinx and percent uninsured from the County Health Rankings database,(University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2012) and percent voting for Barack Obama in the 2012 presidential election (given evidence that partisanship was associated with ACA enrollment (Lerman, Sadin, & Trachtman, 2017)), as well as a measure indicating whether the state had a federally facilitated (vs. state-based or state-sponsorship) marketplace in 2014 (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2014) and Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West). Resources in the public domain, rather than the proprietary Nielsen database, were used to calculate DMAs. Our DMA geographies consisted of unique collections of counties. No counties were divided across multiple DMAs.

Data Analysis

After coding content of each unique ad, we analyzed data at the airings level to account for total volume and geographic distribution of ads that aired (analysis conducted in 2019). First, we quantified the volume of airings of Spanish- vs. English-language ads by OEP. We used chi-squared tests to examine differences by ad sponsor, OEP, and language. We examined differences in mention of online or in-person/telephone enrollment assistance resources by language stratifying by OEP and sponsor. Multivariable logistic regression models estimated the odds of mentioning assistance resources by language, adjusting for OEP, ad sponsor, and the additional covariates described above.

RESULTS

Spanish-language ad airings made up 10.3% of all airings across the three OEPs. Because Spanish-language stations represent 10% of total stations tracked by Kantar, this means that on average Spanish- and English-language stations carried similar numbers of health insurance ads (although a limited proportion of Spanish-language ads aired on primarily English-language stations (<5%)). The proportion of Spanish-language airings increased over time (8.8% in OEP1 to 11.1% in OEP2 to 12.0% in OEP3, p<.001).

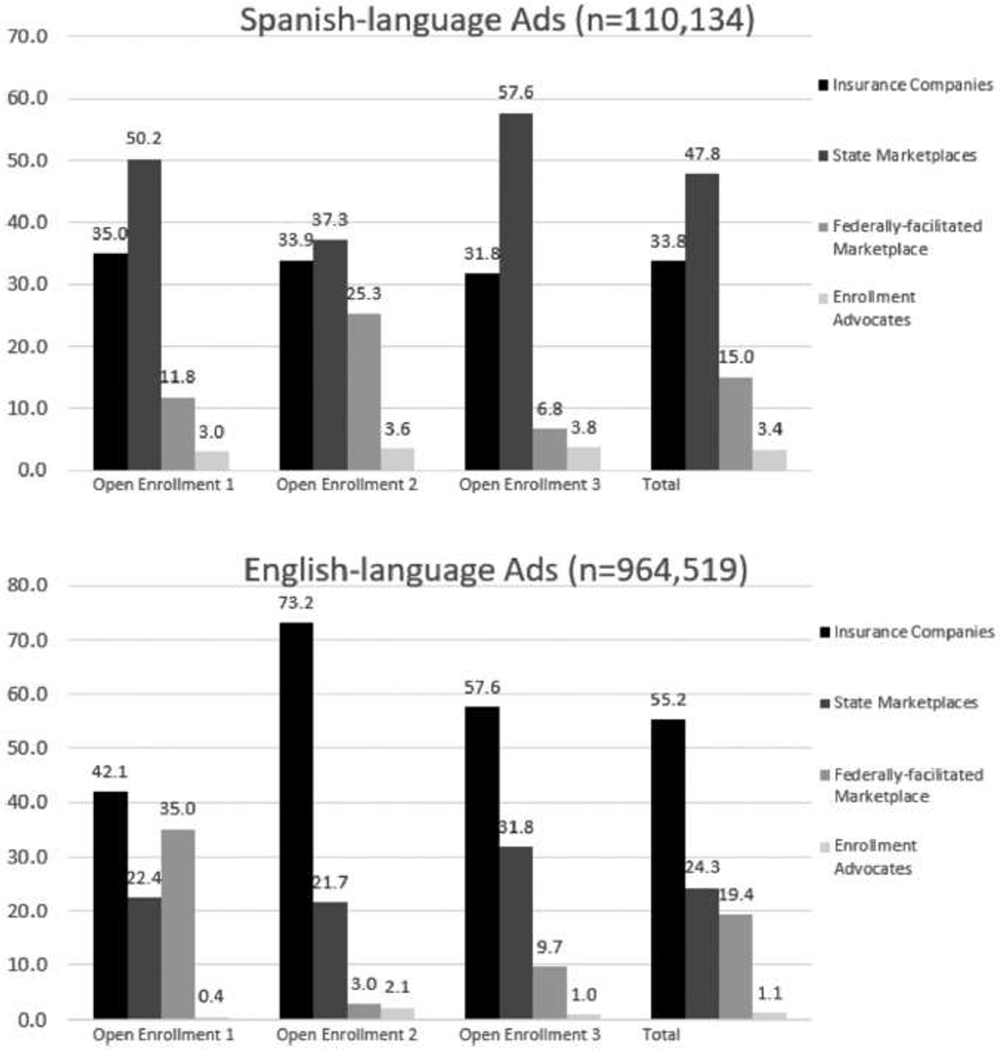

Figure 1 compares the share of Spanish- versus English-language airings by sponsor overall and in each OEP. Only 34% of overall Spanish-language ads were sponsored by insurance companies, compared to 55% of English-language ads (p<.001). Conversely, Spanish-language airings were more likely to be sponsored by state Marketplaces (47.8% compared to 24.3% of English-language ads) (p<.001). Spanish-language ads were more likely than English-language to be sponsored by enrollment advocates (p<.001) and less likely to be sponsored by the federally facilitated Marketplace (p<.001). State Marketplaces were particularly important sponsors of Spanish-language ads in OEP3 when they sponsored 57.6% of all Spanish-language ads versus 6.8% of Spanish-language ads sponsored by the federally facilitated Marketplace.

Figure 1.

Spanish- and English-Language Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings by Ad Sponsor, Open Enrollment Period, and Overall

There were few differences by language in mention of a website, while many differences were observed between Spanish- and English-language ads in mention of telephone/in-person assistance (see Table 1). Spanish-language airings were more likely to provide telephone/in-person assistance resources (71.3% vs. 65%, p<.001), while English-language airings were more likely to mention a website (94.7% vs. 91.6%, p<.001). While mention of telephone/in-person assistance decreased over time for English-language airings (71.4% in OEP1 to 54.7% in OEP3, p<.001), these mentions increased in Spanish-language airings (71.0% to 84.8%, p<.001). In OEP1, there was no difference in mention of telephone/in-person assistance comparing Spanish- and English-language ads, but there was a large difference in website mention (81.4% vs. 97.8%, p<.001). In OEP3, the difference in mention of telephone/in-person assistance was substantial: 84.8% of Spanish-language airings compared to 54.7% of English-language airings (p<.001). The percent mentioning websites was also greater for Spanish- vs. English-language airings in OEP3 (98.8% vs. 90.3%, p<.001). All within-sponsor type differences by language were significant; however, differences in website mentions in insurance company and federal marketplace airings were very small. Differences in telephone/in-person assistance were much larger, especially within federal marketplace airings where only 53.5% of English-language airings mentioned telephone/in-person assistance vs. nearly universal mention in Spanish-language airings (99.1%, p<.001).

Table 1.

Percent of Television Health Insurance Advertisement Airings Providing Viewers with Website/Online or Telephone/In-Person Assistance Enrollment Resources, by Language, Open Enrollment Period, and Ad Sponsor

| Overall | Open Enrollment Period (OEP) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OEP 1 | OEP 2 | OEP 3 | ||||||

| Spanish | English | Spanish | English | Spanish | English | Spanish | English | |

| Number of airings | 110,134 | 964,519 | 43,074 | 447,585 | 37,338 | 299,730 | 29,722 | 217,204 |

|

Provides website |

91.6 | 94.7*** | 81.4 | 97.8*** | 97.7 | 93.2*** | 98.8 | 90.3*** |

| Provides telephone/in-person assistance | 71.3 | 65.0*** | 71.0 | 71.4 | 60.9 | 63.1*** | 84.8 | 54.7*** |

| Ad Sponsor | ||||||||

| Health Insurance Company | Federal Marketplace | State Marketplace | aEnrollment Advocate | |||||

| Spanish | English | Spanish | English | Spanish | English | Spanish | English | |

| Number of airings | 37,177 | 532,872 | 16,539 | 186,762 | 52,670 | 234,355 | 3,748 | 10,530 |

| Provides website | 91.8 | 91.1*** | 100.0 | 99.7*** | 88.3 | 98.7*** | 100.0 | 98.4*** |

| Provides telephone/in-person assistance | 84.1 | 75.1*** | 99.1 | 53.5*** | 58.5 | 51.6*** | 0.9 | 62.7*** |

Notes:

Boldface indicates statistically significant difference between Spanish- and English-language ads (***p<.001)

OEP: Open Enrollment Period

Spanish-language airings had 49% lower odds (0.51, 95%CI: 0.50, 0.53, p<.001) of mentioning a website/online resources to get information on signing up for insurance and more than two times greater odds (2.20, 95%CI: 2.17, 2.24, p<.001) of mentioning telephone/in-person assistance relative to English-language airings in adjusted analyses (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Regression Results: Television Health Insurance Advertisements Providing Viewers with Website or Telephone/In-person Enrollment Resources

| Provides website/online resource for viewers | Provides telephone or in-person assistance as resource for viewers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Language | ||||||

| English-language | REF | REF | ||||

| Spanish-language | 0.51 | (0.50, 0.53) | <.001 | 2.20 | (2.17, 2.24) | <.001 |

| Open enrollment period | ||||||

| OEP1 | REF | REF | ||||

| OEP2 | 0.86 | (0.84, 0.87) | <.001 | 0.42 | (0.41, 0.42) | <.001 |

| OEP3 | 0.52 | (0.51, 0.53) | <.001 | 0.42 | (0.42, 0.43) | <.001 |

| Ad sponsor | ||||||

| State marketplace | REF | REF | ||||

| Insurance companies | 0.33 | (0.32, 0.34) | <.001 | 2.71 | (2.68, 2.74) | <.001 |

| Federally-facilitated marketplace | 10.27 | (9.45,11.14) | <.001 | 0.69 | (0.68, 0.70) | <.001 |

| Enrollment advocates | 3.41 | (2.92, 3.99) | <.001 | 0.70 | (0.68,0.73) | <.001 |

| Media market level | ||||||

| % Latinx/Hispanic | 0.30 | (0.28, 0.33) | <.001 | 0.83 | (0.80, 0.87) | <.001 |

| % uninsured | 11.28 | (8.25, 15.43) | <.001 | 49.81 | (42.77, 58.01) | <.001 |

| Federal marketplace in state, 2014 | 0.78 | (0.78, 0.80) | <.001 | 0.93 | (0.92, 0.94) | <.001 |

| Census region | ||||||

| Northeast | REF | REF | ||||

| Midwest | 0.74 | (0.72, 0.76) | <.001 | 0.64 | (0.63, 0.65) | <.001 |

| South | 0.72 | (0.69, 0.75) | <.001 | 0.44 | (0.43, 0.45) | <.001 |

| West | 0.94 | (0.90, 0.97) | <.001 | 0.24 | (0.23, 0.24) | <.001 |

Notes:

Boldface indicates statistical significance

OR: Odds Ratio

CI: Confidence Interval

OEP: Open Enrollment Period

DISCUSSION

This study indicates that targeting of enrollment resources in health insurance ads differed significantly by language. Navigating a complex health care system and enrollment process can be particularly difficult for immigrants from Latin America/Spanish-speaking countries (Hacker, Anies, Folb, & Zallman, 2015). Recent immigrants, and those who have resided in the U.S. for several years but predominantly speak Spanish, tend to prefer to talk to and interact directly with a person (e.g. “promotores”/navigators) for health information or when enrolling in programs (Cristancho, Peters, & Garces, 2014; Elder et al., 2005; Shommu et al., 2016) as opposed to enrolling online. Completing the process in a space they recognize and/or feel comfortable in is likely to increase rapport, trust, and a sense of security, as is interacting with Spanish-speaking assisters/navigators. Television ads likely play a role in shaping potential enrollees’ knowledge and awareness of enrollment resources. Prior research suggests that Latinx adults prefer in-person/telephone ACA enrollment (Bye, 2014; Garcia Mosqueira et al., 2015). Our finding that Spanish-language ads had over two times the odds of mentioning in-person/telephone enrollment as English-language ads suggests that sponsors were responsive to this preference.

Emphasis on telephone/in person enrollment assistance in Spanish-language ads increased over time. This may reflect concerns with lack of outreach to and enrollment for Latinx populations following the initial OEP1 and increased investment in Hispanic media funding and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services navigator grants for Latinx outreach (Garcia Mosqueira & Sommers, 2016). Mention of online enrollment resources also increased over time. Mention of both telephone/in-person and online resources declined among English-language ads during the same time period, though this decrease was greater for telephone/in-person mentions. This suggests the increase in telephone/in-person emphasis in Spanish-language ads was purposeful. There were also clear patterns by language in mention of resources by sponsor. While mention of online resources was relatively similar across sponsors between English- and Spanish-language ads, there were large differences across sponsors by language for mention of in-person/telephone assistance resources. Importantly, federal marketplace ads in Spanish almost universally mentioned telephone/in-person resources, while only 50% of English ads did, again suggesting a clear strategy to reach consumers with different enrollment preferences.

The number of Latinxs in the U.S. continues to grow, as does the number who speak Spanish. Of the nearly 59 million Latinxs in the U.S., 38 million speak Spanish (United States Census Bureau, 2017). While a smaller share of the Latinx population speaks Spanish than in the past, the number of Spanish speakers has nearly quadrupled over the past 4 decades (Lopez & Gonzalez-Barrera, 2013); and most Latinxs who speak English also speak Spanish (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Latinx adults faced the largest insurance inequities both pre- and post-ACA, with even greater inequities for Spanish-speaking and/or immigrant Latinxs (Artiga, Orgera, & Damico, 2019). Although not all uninsured Latinxs are eligible for new insurance options through the ACA (e.g., Medicaid, individual marketplace) due to income, exclusions based on citizenship/documentation status, or living in a non-Medicaid expansion state, about half of the 10 million nonelderly Latinxs who were uninsured in 2017 were eligible (Artiga et al., 2019). Therefore, it remains important for potential ad sponsors to market to and connect uninsured Latinxs with enrollment resources.

Our analysis reflects ads from OEP1-3, prior to drastic cuts in outreach and marketing funding in 2017 and cutting ties with Latinx-serving organizations with whom the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services had partnered. There are grave concerns that these cuts may have disproportionately hurt Latinxs (Ollstein, 2017), so an understanding of the current landscape of Spanish-language advertising is critical. Given these cuts, insurance companies are now one of the only ad sponsors– save for some state-based Marketplaces. Thus, it is important to understand whether Spanish-language advertising has been sustained and, importantly, that it provides enrollment-related educational information.

Spanish-language ad airings were significantly more likely to be sponsored by state marketplaces, relative to English-language ad airings. Thus, in the current landscape, Spanish-speaking communities in states without state-based Marketplaces may especially face a dearth of federal Marketplace advertising, which would impede their ability to connect to enrollment resources and enroll. For example, Texas did not operate its own state-based Marketplace, and the state Legislature restricted navigator funding for enrollment assistance (Garcia Mosqueira & Sommers, 2016). In contrast, California created the country’s largest state-based Marketplace—Covered California—and provided robust funding for advertising and enrollment assistance. Furthermore, in contrast to other states, California continues to explore further expanding eligibility to persons who are excluded from the ACA such as undocumented immigrant adults (Allyn, 2019). Future research should examine the impact of the severe federal cuts nationally along with state and local level variation. In addition, Latinx and immigrant families are currently experiencing fear and isolation related to the federal policy agenda (escalated deportations and detention, xenophobic policies and rhetoric (Cisneros, 2017), and proposed changes to the definition of public charge), all of which can lead to suppression of engagement in public programs among citizens and noncitizens alike, including health insurance for which they or their family members qualify (Artiga & Ubri, 2017; Batalova, Fix, & Greenberg, 2018; Beniflah, Little, Simon, & Sturm, 2013; Bernstein, Gonzalez, Karpman, & Zuckerman, 2019; Trisi, 2019). Given this hostile, anti-Latinx/-immigrant environment, it will be crucial to continue to monitor the content of advertisements promoting insurance to Spanish-speaking and Latinx consumers. In particular, it will be important to assess whether ad sponsors are addressing fear of enrolling, due to the aforementioned distresses and policy concerns, in their discussion of enrollment resources and the enrollment process (e.g., eligibility in mixed-status families, data security, data sharing).

LIMITATIONS

First, our analysis of Spanish-language ads does not encompass all advertising targeted to Latinxs, since Kantar/CMAG does not track Spanish-language stations in all 210 media markets and English-language ads were also targeted to Latinxs. Second, the generally high levels of interrater reliability are limited to coding of the English-language ads; the Spanish-language ads were coded by a single author. However, we expect that differences in coding between Spanish- and English-language ads were minimal since the three coders underwent comprehensive training and worked together closely during pilot testing of the coding instrument to debrief and discuss differences in coding in order to ensure reliability in coding between English- and Spanish-language ads. Third, our measure of percent Latinx does not capture within-group differences among the heterogeneous Latinx community. Fourth, we selected TV ads that were aired during the time period of the three OEPs when eligible individuals could enroll in plans on the new state and federal Marketplaces. We were not able to distinguish between ads from private insurers that had Marketplace plans vs. only available through other means (e.g., off-exchange individual market plans and/or employer-sponsored insurers). Fifth, we only analyzed television ads; other forms of marketing—such as radio, digital, or print—may be important forms of outreach, generally, or for Latinx communities specifically. Future research could explore these alternative channels. Finally, our study only examined ads from OEPs in 2014-2016. Given the xenophobic sociopolitical environment and drastic federal cuts to ACA outreach and marketing during the Trump administration, it is likely that our findings could have been drastically different had we examined ads in subsequent OEPs. Future studies should examine the volume and content of post-2016 Spanish-language ads.

CONCLUSION

Messaging in and sponsorship of health insurance television advertising differed significantly by language, as well as over time. Spanish-language ad airings were much more likely to emphasize telephone and/or in-person enrollment resources, a promising finding given that Latinxs who received such assistance were more likely to enroll (Garcia Mosqueira & Sommers, 2016). Continued attention to Spanish-language Marketplace television advertising is important in order to understand the volume and content of information to which potentially eligible uninsured Latinxs are exposed.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest statement: The funding agency, Robert Wood Johnson State Health Access Reform Evaluation (SHARE) (grant 72179, co–principal investigators SG and EF), had no involvement in the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, or writing and submission of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of RWJ. The following authors also received support from their institutions: Drexel University (CA), Wesleyan University (LB and EF), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (SB and KA), and the McKnight Land-Grant Professorship, University of Minnesota (SG).

References

- Allyn B (2019, July 10). California Is 1st State To Offer Health Benefits To Adult Undocumented Immigrants. National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2019/07/10/740147546/california-first-state-to-offer-health-benefits-to-adult-undocumented-immigrants [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S (2013). Health Coverage By Race and Ethnicity: The Potential Impact of the Affordable Care Act. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S, Orgera K, & Damico A (2019). Changes in Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity since Implementation of the ACA, 2013-2017. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation; Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/changes-in-health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-since-implementation-of-the-aca-2013-2017/ [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S & Ubri P (2017). Living in an Immigrant Family in America: How Fear and Toxic Stress are Affecting Daily Life, Well-Being, & Health. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation; Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/living-in-an-immigrant-family-in-america-how-fear-and-toxic-stress-are-affecting-daily-life-well-being-health/ [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Bandara S, Arnold KT, Kemmick Pintor J, Baum LM, Niederdeppe J, et al. (2018). Assessing the content of television health insurance advertising during three open enrollment periods of the ACA. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 43(6), 961–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batalova J, Fix M, & Greenberg M (2018). Chilling Effects: The Expected Public Charge Rule and Its Impact on Legal Immigrant Families’ Public Benefits Use. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation; Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/ProposedPublicChargeRule-Final-Web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Beniflah JD, Little WK, Simon HK, & Sturm J (2013). Effects of immigration enforcement legislation on Hispanic pediatric patient visits to the pediatric emergency department. Clinical Pediatrics, 52(12), 1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein H, Gonzalez D, Karpman M, & Zuckerman S (2019). With Public Charge Rule Looming, One In Seven Adults In Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs In 2018. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute; Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/public-charge-rule-looming-one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018 [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2017. ). 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau; Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante AV, Fang H, Rizzo JA, & Ortega AN (2009). Heterogeneity in health insurance coverage among US Latino adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3), 561–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bye L (2014). Covered California: Consumer Tracking Survey. San Francisco, CA: National Opinion Research Center; Retrieved from https://hbex.coveredca.com/data-research/library/NORC%20Consumer%20Tracking%20Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, & Ortega AN (2016). Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Medical Care, 54(2), 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros JD (2017). Racial Presidentialities: Narratives of Latinxs in the 2016 Campaign. Journal of Rhetoric and Public Affairs, 20(3), 511–524. [Google Scholar]

- Coe E, Cordina J, Jones EP, & Rivera S (2015, August 26). Insights Into Hispanics’ Enrollment On The Health Insurance Exchanges. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150826.050146/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Cristancho S, Peters K, & Garces M (2014). Health information preferences among Hispanic/Latino immigrants in the U.S. rural Midwest. Global Health Promotion, 21(1), 40–49. doi: 10.1177/1757975913510727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty MM, Gunja MZ, Collins SR, Beutel S (2016). Latinos and Blacks Have Made Major Gains Under the Affordable Care Act, But Inequalities Remain. Washington, D.C.: The Commonwealth Fund; Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2016/latinos-and-blacks-have-made-major-gains-under-affordable-care-act-inequalities-remain [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell NR, Slymen D, Lopez-Madurga ET, Engelberg M, & Baquero B (2005). Interpersonal and print nutrition communication for a Spanish-dominant Latino population: Secretos de la Buena Vida. Health Psychology, 24(1), 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2014). State Health Insurance Marketplace Types, 2014. Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Mosqueira A, Hua LM, & Sommers BD (2015). Racial differences in awareness of the Affordable Care Act and application assistance among low-income adults in three southern states. Inquiry, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Mosqueira A, & Sommers B (2016). Better Outreach Critical to ACA Enrollment, Particularly for Latinos. Washington, D.C: The Commonwealth Fund; Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2016/better-outreach-critical-aca-enrollment-particularly-latinos [Google Scholar]

- Ghaddar S, Byun J, & Krishnaswami J (2018). Health insurance literacy and awareness of the Affordable Care Act in a vulnerable Hispanic population. Patient Education & Counseling, 101(12), 2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Baum L, & Fowler EF (2014). First impressions: Geographic variation in media messages during the first phase of ACA implementation. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 39(6), 1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Wilcock A, Fowler EF, Barry CL, Niederdeppe J, Baum L, & Karaca-Mandic P (2018). TV advertising volumes were associated with insurance marketplace shopping and enrollment in 2014. Health Affairs, 37(6), 956–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Anies M, Folb BL, & Zallman L (2015). Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: a literature review. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 8, 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Cancio S, & Rivera L (2014). Lack of Awareness of Health Insurance Marketplace Accounts for Low Latino Enrollment. Washington, D.C: Families USA; Retrieved from https://familiesusa.org/blog/2014/02/lack-awareness-health-insurance-marketplace-accounts-low-latino-enrollment [Google Scholar]

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute (2012). County Health Rankings, 2012. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca-Mandic P, Wilcock A, Baum L, Barry CL, Fowler EF, Niederdeppe J, & Gollust SE (2017). the volume of tv advertisements during the ACA’s first enrollment period was associated with increased insurance coverage. Health Affairs, 36(4), 747–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad JM, & Gonzalez-Barrera A (2015). A Majority of English-speaking Hispanics in the US are Bilingual. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/24/a-majority-of-english-speaking-hispanics-in-the-u-s-are-bilingual/ [Google Scholar]

- Lerman AE, Sadin ML, & Trachtman S (2017). Policy uptake as political behavior: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act. American Political Science Review, 111(4), 755–770. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MH, & Gonzalez-Barrera A (2013). What is the Future of Spanish in the United States? Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/05/what-is-the-future-of-spanish-in-the-united-states/ [Google Scholar]

- McDonough M, Bateman C, Barron C, Vega R, Senerchia S, & Maxwell J (2014). Readiness to Implement the Affordable Care Act in the Latino Community Among Health Centers and Community-Based Organizations. Washington, D.C: Unidos US; Retrieved from http://publications.unidosus.org/bitstream/handle/123456789/1088/readinesstoimplementaca_ib.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- Ollstein A (2017, November 1). Hispanic Caucus Slams HHS For Silence On Cuts To Obamacare’s Latino Outreach. Talking Points Memo. Retrieved from https://talkingpointsmemo.com/dc/latino-open-enrollment-trump-hispanic-caucus [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, Rodriguez HP, & Vargas Bustamante A (2015). Policy dilemmas in Latino health care and implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Annual Review of Public Health, 36, 525–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C, & Dreas C (2011). Three Things You Thought You Knew About U.S. Hispanic’s Engagement With Media...And Why You May Have Been Wrong. New York, NY: Nielsen Media; Retrieved from https://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/corporate/us/en/newswire/uploads/2011/04/Nielsen-Hispanic-Media-US.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MA, Bustamante AV, & Ang A (2009). Perceived quality of care, receipt of preventive care, and usual source of health care among undocumented and other Latinos. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24 Suppl 3, 508–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez G (2015). New Mexico Survey Provides New Insights on Latinos and ACA. Seattle, WA: Latino Decisions; Retrieved from http://www.latinodecisions.com/blog/2015/08/14/new-mexico-survey-provides-new-insights-on-latinos-and-aca/ [Google Scholar]

- Shafer PR, Fowler EF, Baum L, & Gollust SE (2018). Television advertising and health insurance marketplace consumer engagement in Kentucky: A natural experiment. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(10), e10872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shommu NS, Ahmed S, Rumana N, Barron GRS, McBrien KA, & Turin TC (2016). What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: A systematic scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 6. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0298-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trisi D (2019). Trump Administration’s Overbroad Public Charge Definition Could Deny Those Without Substantial Means a Chance to Come to or Stay in the U.S. Washington, D.C: Center on Budget & Policy Priorities; Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/trump-administrations-overbroad-public-charge-definition-could-deny [Google Scholar]

- Zong J, Batalova J, & Burrows M (2019). Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States. Washington, D.C: Migration Policy Institute; Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states [Google Scholar]