Abstract

Zinc (Zn) has emerged as a promising bioresorbable stent material due to its satisfactory corrosion behavior and excellent biocompatibility. However, for load bearing implant applications, alloying is required to boost its mechanical properties as pure Zn exhibits poor strength. Unfortunately, an increase in inflammation relative to pure Zn is a commonly observed side-effect of Zn alloys. Consequently, the development of a Zn-based alloy that can simultaneously feature improved mechanical properties and suppress inflammatory responses is a big challenge. Here, a bioresorbable, biocompatible Zn-Ag-based quinary alloy was comprehensively evaluated in vivo, in comparison to reference materials. The inflammatory and smooth muscle cellular response was characterized and correlated to metrics of neointimal growth. We found that implantation of the quinary alloy was associated with significantly improved inflammatory activities relative to the reference materials. Additionally, we found that inflammation, but not smooth muscle cell hyperplasia, significantly correlates to neointimal growth for Zn alloys. The results suggest that inflammation is the main driver of neointimal growth for Zn-based alloys and that the quinary Zn-Ag-Mn-Zr-Cu alloy may impart inflammation-resistance properties to arterial implants.

Keywords: Biodegradable Stent, Zinc Alloy, Neointima, Inflammation, Biocompatibility

Graphical Abstract

1.0. Introduction

Zn has emerged as a promising bioresorbable stent (BRS) material due to its ideal corrosion behavior and excellent biocompatibility1–4. However, pure Zn lacks the mechanical strength required to serve as a vascular scaffold5. As a result, numerous investigators have alloyed Zn with a wide range of elements followed by thermomechanical treatments aimed at improving its strength, primarily through promotion of solid solution and grain refinement strengthening6. However, a fundamental consideration when increasing the mechanical strength is to avoid worsening the biocompatibility relative to pure Zn.

It is well known that the implantation of foreign material into an organism evokes an inflammatory response, whose purpose is to contain, neutralize, and/or remove the material7. For biostable inert materials, inflammation quickly resolves as phagocytes are unable to remove the foreign body, eventually leading to fibrous encapsulation7. On the contrary, materials that are designed to biocorrode are highly interactive with the host environment. Macrophages in particular are continuously present at the implant interface where they work to break down the implant, a process that results in the sustained release of corrosion byproducts for the lifetime of the implant. Because an aggressive inflammatory environment is harmful to the neighboring tissue and may increase the size and variability of neointimal (NI) formations surrounding the implant, Zn alloys must be engineered with the objective of minimizing the inflammatory response.

Due to the importance of the inflammatory response in contributing to the restenosis of stented arteries8, we have been motivated to develop Zn-based BRS materials that either avoid provoking or actively suppress inflammatory responses. In order to design inflammation-resistant materials, it is necessary to clarify the relationship between material characteristics and biological responses. Our wire implantation model has allowed us to observe and quantify neointimal responses to many Zn-based materials. With such an approach, we are able to relate material properties with the biological responses. For example, our early exploratory work demonstrated that particular corrosion characteristics related to incremental wt.% increases of aluminum (added to improve mechanical properties9) produced strikingly different inflammatory profiles, suggesting a relationship between material properties and inflammation10. A consistent theme that has emerged from our recent investigative work has been that the alloying of pure Zn is associated with worsened inflammation and NI growth11. For instance, alloying with Mg leads to an excessive NI growth accompanied by an increase in inflammation11, 12. Alloying with Li also decreases biocompatibility due to an increase in inflammation relative to pure Zn implants11. While the reason for this association is presently unclear, alloying of Zn may be unavoidable to increase the mechanical properties of Zn for stenting applications. Therefore, the development of Zn-based alloys that can improve mechanical properties without eliciting harmful inflammatory responses relative to pure Zn and inert materials would represent a major advance for the biodegradable implant field.

Silver (Ag) has recently been introduced as a promising alloying addition to Zn due to its ability to improve tensile strength via grain refinement13 and its acceptable biocompatibility and pronounced antimicrobial properties. Indeed, Ag promotes antibacterial activity in a wide range of chemical states to effectively kill some superbugs that cannot be treated by most antibiotics14, 15. Moreover, our group recently reported that the addition of manganese (Mn) to the Zn-Ag alloy system further increased the tensile strength and fracture elongation due to the grain refinement arisen from Mn particles16. Copper (Cu) has also gained interest as a potential alloying addition due to its distinct grain refining17, 18 and antibacterial properties since its incorporation into several metals enhances the resistance to bacteria such as S. aureus and E. coli19. Moreover, it has been shown that Cu stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and enhances angiogenesis19. Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated a promising corrosion rate and biocompatibility of binary ZnCu alloy stents implanted into porcine arteries for up to 2 years20. Ultimately, we introduced trace quantity of zirconium (Zr), which is known as the most effective grain refiner. The addition of Zr strongly promotes dynamic recrystallization of the alloy during processing, which results in a remarkably fine microstructure21, 22.

The present work aimed to evaluate the in vivo performance of the recently formulated Zn-Ag based alloys including binary Zn-4Ag (wt%)13, ternary Zn-4Ag-0.6Mn (wt%)16, and quinary Zn-4Ag-0.8Cu-0.6Mn-0.15Zr (wt%) alloys as promising candidate materials for BRS application. Our group previously developed an implant model wherein materials of experimental compositions are drawn into wires and implanted into the abdominal aorta of rats to simulate a stent strut degrading in the arterial space11. Here, we make use of this model to compare the three zinc alloys relative to pure Zn and biostable Pt controls. Cell populations within the neointima that formed around the different materials were characterized using standard histology and immunofluorescence techniques. Interestingly, we found a significant reduction of inflammatory activities by the quinary alloy relative to the other Zn-based materials. Surprisingly, we found that inflammation, but not smooth muscle cell hyperplasia, is correlated with neointimal growth for Zn alloys.

2.0. Materials and Methods

2.1. Implanted Materials

In this study, binary Zn-4Ag, ternary Zn-4Ag-0.6Mn, and quinary Zn-4Ag-0.8Cu-0.6Mn-0.15Zr alloys were investigated and compared to pure zinc (Zn) and pure platinum (Pt) controls. To produce the alloys, Zn splat shot (99.995%), Ag splat shot (99.95%), Cu splat shot (99.9%), Mn powder (99.995%), and Zr lump (99.8%) were melted at 700 °C in cylindrical graphite crucibles inside a resistance furnace, producing cast cylindrical billets with a diameter and length of 28 mm and 100 mm, respectively. Table 1 lists the compositions of all the produced alloys. In order to homogenize the cast structure, annealing was carried out for 4h at 350 °C for the binary and at 400 °C for the ternary and quinary alloys, followed by water quenching. Annealed samples were subsequently extruded at 310°C with an extrusion ratio and speed of 39:1 and 5 mm/min, respectively, to obtain cylindrical rods.

Table 1.

ICP compositional analysis of the proposed alloys (in wt%).

| Alloy code | Ag | Cu | Mn | Zr | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A4 | 4.04±0.31 | - | - | - | Bal. |

| AM41 | 3.91±0.17 | - | 0.55±0.07 | - | Bal. |

| ACMZ4110 | 3.88±0.24 | 0.76±0.08 | 0.62±0.11 | 0.13±0.05 | Bal. |

The extruded rods of 4 mm in diameter were centerless ground to provide a pristine surface finish and were then drawn into wires with a diameter of 0.25 mm by Fort Wayne Metals (Fort Wayne, IN). The Zn (ZN005115) and Pt (PT005120) control wires also with a diameter of 0.25 mm were purchased from Goodfellow © (Coraopolis, PA).

2.2. Reagents

For Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining, reagents included neutral buffered formalin solution 10%, phosphate buffered saline (PBS), Gill’s hematoxylin No. 3 solution, hydrochloric acid 37% (HCl), absolute ethanol, Eosin Y disodium salt, acetic acid 99.7%, xylene substitute, and Eukitt® quick-hardening mounting medium; all were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Burlington, MA).

For immunofluorescence, reagents included methanol obtained from EMD Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany), paraformaldehyde (4% formaldehyde prepared in PBS) and Streptavidin alexa flour 488 conjugate obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), and goat serum, 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), and flouromount aqueous mounting medium; all obtained from Sigma Aldrich (Burlington, MA). Primary antibodies included anti-CD68 (ab125121), anti-iNOS (ab15323), and anti-αSMA (ab5694). Secondary antibodies included biotinylated goat antirabbit IgG (ab6720) and goat antirabbit IgG alexa flour 488 (ab150077). All antibodies and an endogenous biotin/avidin blocking kit (ab64212) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA).

2.3. In Vivo Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Implantation and Cryo-sectioning

The procedure for arterial implantation and cryo-sectioning has been previously described in detail11. Briefly, Pt, Zn, binary, ternary, and quinary wires (250 μm diameter) approximately 1.5 cm in length were sanitized in 70% (v/v) ethyl alcohol prior to implantation. Sharpened wires were used to penetrate the wall of the abdominal aorta of female adult Sprague-Dawley rats, advanced approximately 1 cm through the lumen, and punctured out the other side. The wires were left in the lumen, with around 2–3 mm of wire exteriorized from the artery at both ends. The Zn wires were left in the artery for 3 and 6 months while the Pt and Zn alloys remained in the arteries for 6 months. When the rats were euthanized at experimental end points, each aorta with the wire was dissected and excised, surrounded in PolyFreeze cryo-medium, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in a −80°C freezer until cryo-sectioning. All animal experiments were approved by the animal care and use committee (IACUC) of Michigan Technological University. The wire containing arteries were cross sectioned using an HM525 NX cryomicrotome from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The cross sections were taken at a thickness of 10 μm and placed on Histobond glass slides. Multiple cross sections spanning approximately a 0.2 mm distance were taken from each sample for analysis.

2.3.2. Hematoxylin-Eosin Staining

Slides with tissue sections were fixed with neutral buffered formalin solution at room temperature for 10 mins and then washed in PBS three times for 5 mins each. H&E staining was performed using previously described methods to qualitatively visualize overall vessel morphology and tissue formation surrounding the implant10. The samples were imaged using an Olympus BX51, DP70 bright-field microscope (Upper Saucon Township, PA).

2.3.3. Immunofluorescence

The immunofluorescence protocols slightly varied between α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS labeling in order to optimize each protocol for signal intensity and specificity. Tissue sections labeled for α-SMA were fixed in ice cold methanol for 5 mins. Tissue sections labeled for CD68 and iNOS were fixed in absolute ethanol for 2 mins at room temperature. Following fixation, the tissue sections were washed in three changes of PBS and incubated in 10% (v/v) goat serum diluted in PBS for 30 mins. Sections labeled using the biotinylated secondary antibody/streptavidin system (CD68 and iNOS) were immersed in an endogenous biotin and avidin blocking kit for 10 mins each. The tissue sections were then incubated in their respective primary antibodies. The antibodies were diluted with PBS to a concentration of 1:250 (v/v) for α-SMA, 1:100 (v/v) for CD68, and 1:50 (v/v) for iNOS. α-SMA and CD68 labeled sections were incubated in the primary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature and the iNOS labeled sections were incubated overnight at 4°C. The sections labeled for α-SMA were incubated in a 1:300 (v/v) PBS dilution of secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature. The CD68 and iNOS labeled sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibodies and then streptavidin for 1 hour each at room temperature, which were both diluted to 1:500 (v/v) in PBS. All sections were then incubated with a DAPI working solution (5 μg/mL) diluted with PBS to 1:1000 (v/v) for 2 mins at room temperature. Two PBS rinses were performed between all steps of the protocol. Coverslips were then mounted on the slides using flouromount aqueous mounting medium. The samples were immediately imaged using the appropriate fluorescent filters.

2.3.4. Immuno-Fluorescence and Neointimal Morphometric Quantification

A minimum of two cross sections per sample, separated by a distance of approximately 100 μm, were used for quantitative immuno-fluorescence analysis. Two to four locations (depending on the size of the NI) of the NI from each cross section were imaged at 600x normal magnification. For each location, MetaMorph image processing software was used to threshold the image to quantify positive antibody (either α-SMA, CD68, or iNOS) signal (positive pixel count) and the NI area was determined by outlining the corresponding DAPI image. The sum of the positively thresholded antibody signal was normalized to the sum of the NI area between all the images for each cross section. The normalized value was averaged for all of the cross sections evaluated for each sample. The overall wire lumen thickness (WLT – the neointima tissue thickness between the implant and the arterial lumen) and neointimal area (NA– the area of the neointima tissue surrounding the implant) of each cross section were measured using DAPI images taken at 100x normal magnification in order to perform a paired correlation analysis between immuno-fluorescence signal and overall NI morphometrics. WLT and NA were measured using methods previously described11. For all immuno-fluorescence quantification, the images were randomized and the technician was blind to the sample being evaluated.

2.4. In Vitro Experimental Methods

2.4.1. Corrosion and ICP-OES Analysis

Quinary and ternary wires were corroded in hanks balanced salt solution in an aerated environment at 37 ± 1 ºC, with the pH adjusted to 7.4 using 1 M NaOH or HCl23. The corrosion extracts were collected after 14 days for analysis. The extract supernatants were then filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter. After filtration, the solutions were acid digested with trace metal basis nitric acid and analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) to determine the presence/concentration of ionic Cu within the corrosion solutions. The detection limit of the ICP-OES system was 10 PPB for Cu. Three replicates were performed for each alloy. A portion of the corrosion extracts was saved prior to filtering and acid digestion for the nitric oxide (NO) release experiments.

2.4.2. Nitric Oxide Generation

S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) is a synthetic S-nitrosothiol (RSNO) that has been extensively studied as an in vitro NO donor to simulate the physiological environment24, 25. We used SNAP to quantify the ability of the corrosion extracts to catalyze NO release from RSNOs. 1mM SNAP solutions were prepared using powdered SNAP (ab120014, abcam) and PBS treated with chelex 100 resin (sodium form, Sigma-Aldrich) to remove any trace metal impurities. The SNAP solutions were remade every 2 hours and placed on ice until use. The capability of the corrosion extracts to generate NO was evaluated by injecting 100 μL of the respective corrosion solutions into 1 mL of the SNAP solution. NO release was measured via chemiluminescence using a Siever’s 280i Nitric Oxide Analyzer (NOA) (Boulder, CO). The SNAP solutions were added into a NO sample vial attached to the NOA. Nitrogen gas was bubbled through the SNAP solution to force NO out of solution. Nitrogen gas was also used as a sweep gas to carry released NO from the sample vile into the NOA. The NO release from the SNAP solutions were allowed to equilibrate for 2 minutes before the corrosion extracts were injected. Following the injection of the corrosion extract, the NO release was measured for 8 minutes. Four replicates were performed and averaged to represent each corrosion extract. The three corrosion extracts were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation of NO generation for each alloy.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The normalized α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS data are presented in boxplots. For each box, the central line represents the median and the bottom and top edges represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the highest and lowest data points that are not considered outliers, and outliers are represented by the “+”. Every black dot represents an individual sample.

When plotted in a histogram, the normalized α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS data all appeared to follow a right skewed distribution (data not shown). A Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to assess the normality of the normalized α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS data distribution26. All three markers failed the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (p < 0.005 for all three markers). Therefore, a log transformation was applied to the data prior to statistical testing. For α-SMA, a one-way anova followed by a Tukey-Kramer post hoc test was applied to evaluate differences between groups. For CD68 and iNOS, F-tests were applied to evaluate differences in variance between the Zn-based materials relative to the Pt control. A Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS with WLT and NA. The ICP Cu concentration data and NO release data is presented as the mean ± the standard deviation. A Welch’s t-test was used to test the difference between groups. For all statistical tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.0. Results

3.1. In Vivo Results

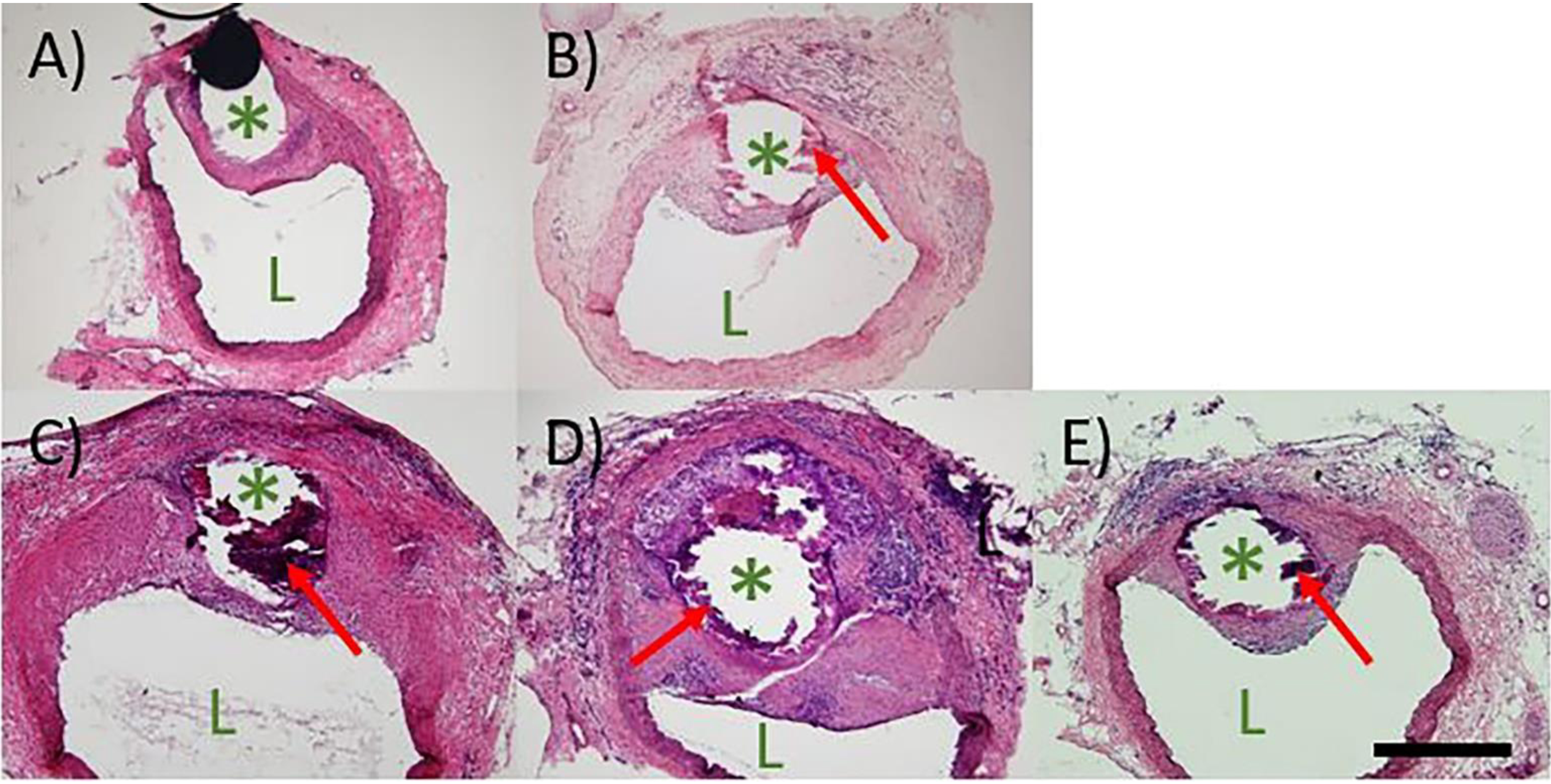

3.1.1. Hematoxylin and Eosin

H&E staining of arteries containing implanted materials was performed to qualitatively observe the biological response. H&E stains shown in Figure 1 represent the most unfavorable biological response from all the cross sections evaluated for each material. In Figures 1A and 1B, low to moderate neointimal growth is seen over the platinum and Zn control materials, respectively. For Zn and the three Zn alloys, a dark corrosion layer is present between the wire implant and the surrounding tissue, Figure 1B–E. As expected, a corrosion layer is not present around the Pt implant. The binary and ternary wires, shown in Figure 1C and D, respectively, were surrounded by neointimas markedly larger in size than those of the Zn and Pt wires, resulting in a higher degree of luminal occlusion. The cross section of the binary alloy displays moderate to high neointimal activation and spreading with a high density of cells at the neointimal apex, which appear to be inflammatory in nature. The ternary implant elicited the worst response, resulting in the largest NA and WLT. Cells of inflammatory origin populate the neointima of the ternary alloy in high density at the implant interface, particularly on the abluminal side of the implant. High density pockets of inflammatory cells can also be seen near the endothelium, suggesting their active recruitment in an ongoing inflammatory response. In sharp contrast to the trend of worsened neointimal responses with sequential Ag and Mn additions, the most favorable response to an experimental alloy was elicited by the quinary alloy. As shown in Figure 1E, the neointimal formation for the quinary alloy resembles that of the Pt and Zn control materials.

Figure 1.

H&E staining of A) Pt, B) Zn, C) Binary, D) Ternary, and E) Quinary implants at 6 months. The images depict the worst biological response from each group. In each image, “L” indicates the lumen of the artery and “*” indicates the wire implant location. Red arrows indicate corrosion product. All images were taken at 100X normal magnification. The scale bar is 500 μm.

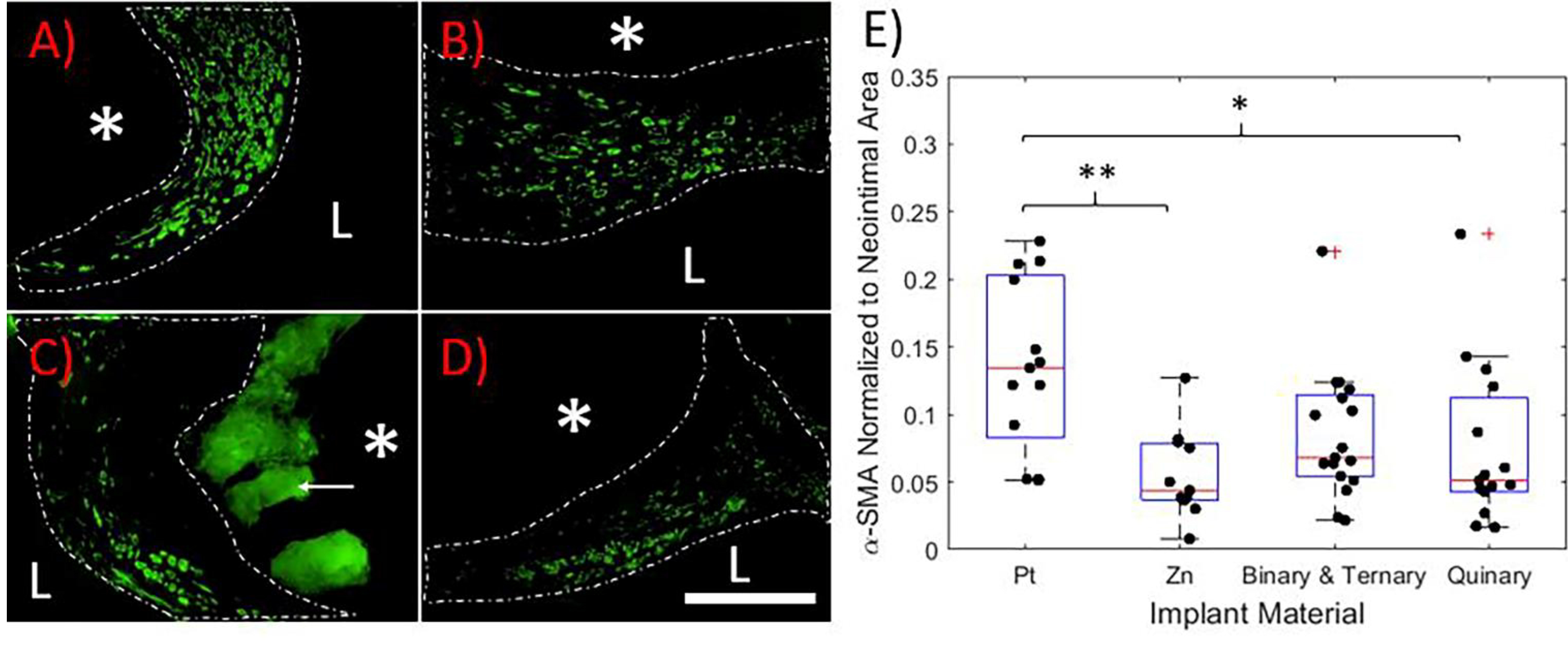

3.1.2. α-SMA Immunofluorescence

Because smooth muscle cells typically predominate in neointimal formations surrounding arterial implants, α-SMA antibody labeling was used to detect the vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) presence and distribution within the neointima of the implants. A representative image for each group is shown in Figure 2A–D. α-SMA+ cells were found in NIs surrounding all implant materials. A strong α-SMA signal was uniformly distributed throughout the NIs surrounding Pt implants. A common theme for the Zn-based implants was an increasing α-SMA signal gradient away from the implant surface. Low to no signal was seen in tissue at the implant interface.

Figure 2.

α-SMA antibody labeling of A) Pt, B) Zn, C) Ternary, and D) Quinary containing arterial cross sections. Representative images are shown. In each image, the white dashed line outlines the neointima, the “L” identifies the lumen of the artery, and the “*” identifies the location of the implant. The white arrow points to auto-fluorescing corrosion product, which is clearly distinguishable from positive signal. All images were taken at 600X normal magnification. The scale bar is 100 μm. E) Box plot of positive α-SMA signal normalized to NI area. P values were obtained by a one-way ANOVA/Tukey Kramer post hoc test. *p < 0.05, **p<0.01

NI α-SMA signal coverage was quantified and normalized to NI area, shown in Figure 2E. Binary and ternary samples were pooled together to increase statistical power (n = 17). The α-SMA signal coverage was significantly reduced for both Zn (n = 11) and the quinary alloy (n = 15) relative to Pt (n = 13) (p = 0.004 and p = 0.024, respectively). The combined binary and ternary alloys followed this trend but were not statistically different from Pt (p = 0.167). There was no difference between any of the Zn-bearing implants in terms of VSMC suppression.

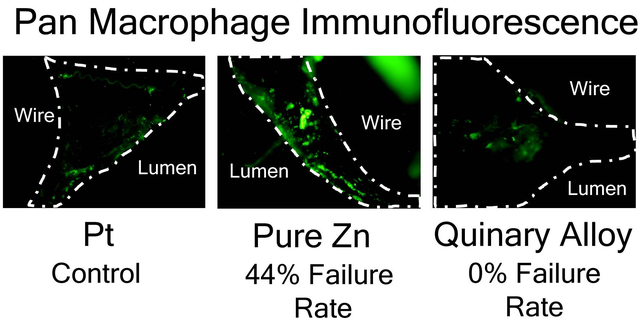

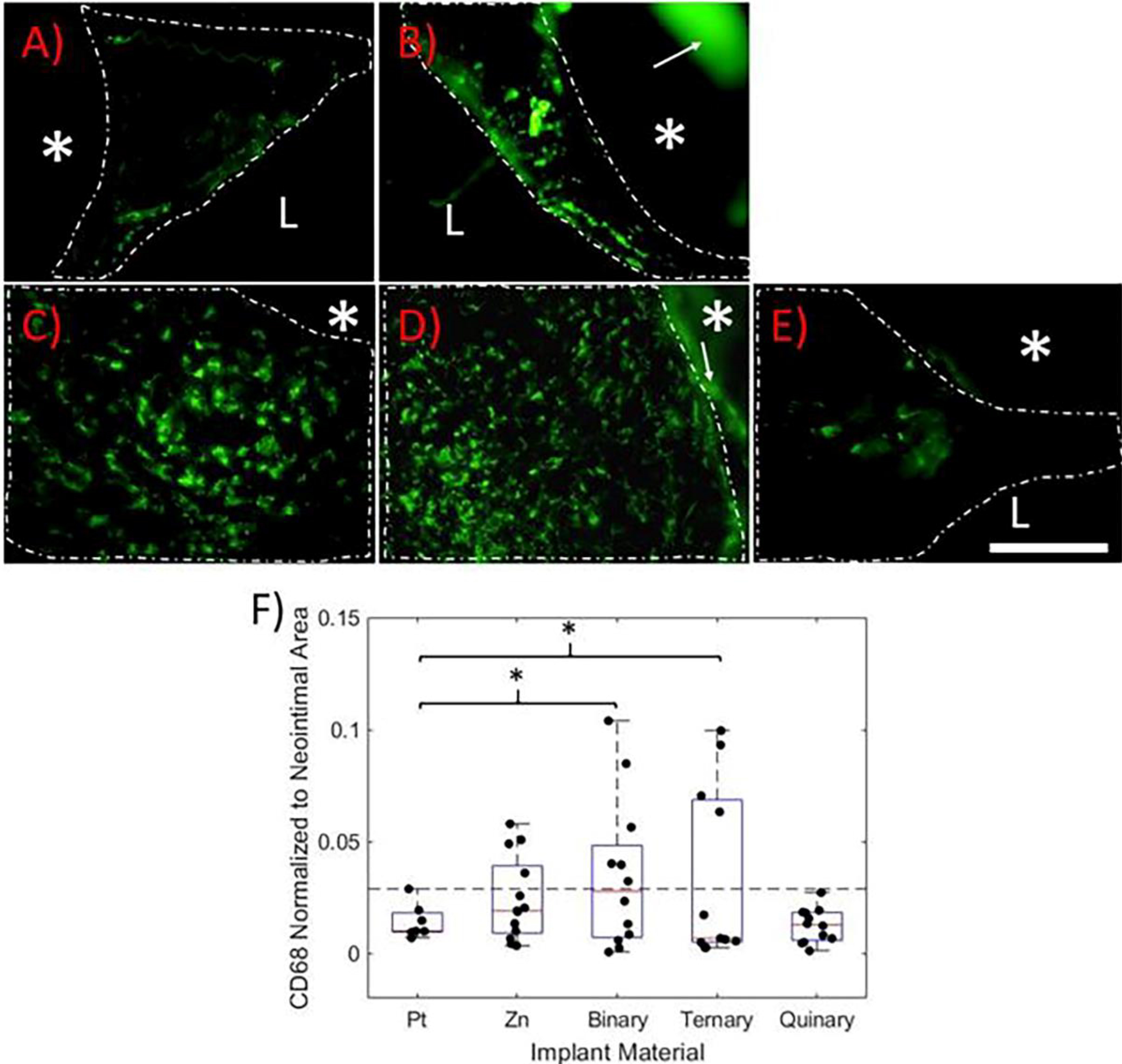

3.1.3. CD68 Immunofluorescence

The CD68 glycoprotein, known to be widely expressed by monocyte/macrophage populations, was labelled to identify these cell types within the neointimas27, 28. Images shown in Figure 3A–E represent the highest CD68 signal coverage for each material. CD68 immunofluorescence was used to quantify the degree of inflammation elicited by the different materials. CD68+ cells were found uniformly distributed throughout the NIs surrounding the Zn-based implants. NIs surrounding Pt implants experienced low CD68 expression that localized near the endothelium. NI CD68 coverage was quantified and normalized to NA (Figure 3F). A CD68 failure threshold was defined as the Pt control sample with the highest CD68 value (dashed line in Figure 3F). Four out of the nine Zn samples (44%), six out of the twelve binary samples (50%), and four out of the eleven ternary samples (36%) had CD68 values above the failure threshold. Surprisingly, all eleven of the quinary samples had CD68 values below the failure threshold. To evaluate the variability of the CD68 coverage, F-tests were performed between all of the Zn-based materials relative to the Pt control group (n = 7). Both the binary and ternary groups had significantly higher variances than the platinum control group (p = 0.0113, n = 12 and p = 0.0146, n = 11, respectively). In contrast, pure Zn and quinary alloy variances were not significantly different from Pt (p = 0.129, n = 13 and p = 0.1737, n = 11, respectively).

Figure 3.

CD68 immunofluorescence labeling of A) Pt, B) Zn, C) Binary, D) Ternary, and E) Quinary implants at 6 months. The images represent the highest CD68 coverage for each group. In each image, the white dashed line outlines the neointima. The “L” identifies the arterial lumen and the “*” identifies the implant. The white arrows point to auto-fluorescing corrosion product, which is clearly distinguishable from positive CD68 signal. All images were taken at 600X normal magnification. The scale bar is 100 μm. F) Box plot of positive CD68 signal coverage normalized to neointimal area. The horizontal dashed line represents the CD68 failure threshold. P values were obtained using an F test relative to the Pt control group *p<0.05

3.1.4. iNOS Immunofluorescence

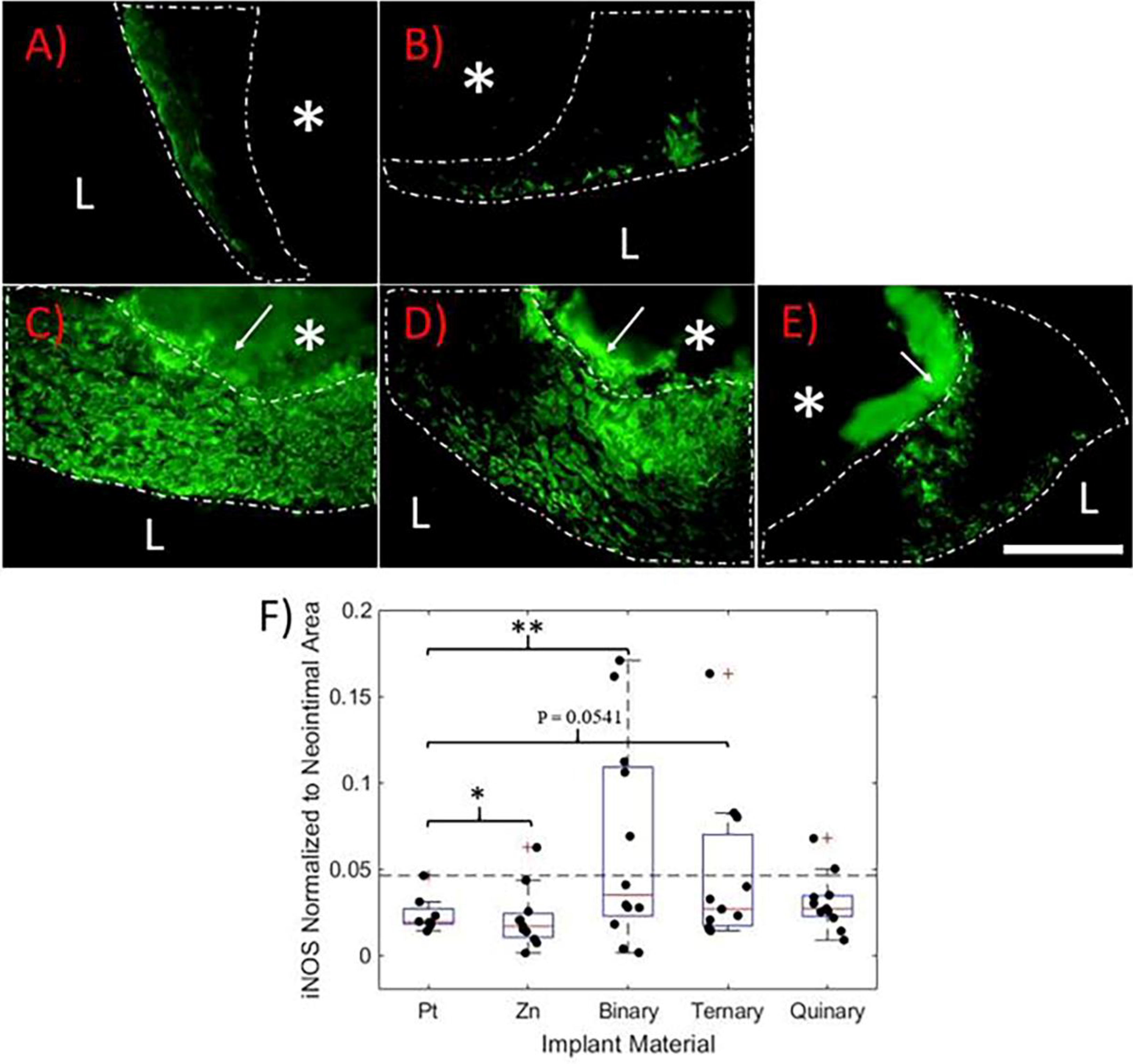

Since inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS2) is highly expressed by macrophages of the aggressive pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype29, 30, iNOS immuno-labeling was used to identify neointimas experiencing an unresolved chronic inflammation (Figure 4). Images shown in Figure 4A-E represent the highest iNOS signal detected for each material. iNOS+ cells were found in the NIs surrounding all implants and were uniformly distributed throughout the NIs surrounding the Zn-based implants, similar to CD68. However, the iNOS+ cells were localized to or near the endothelium in the NIs surrounding the Pt implants. NI iNOS signal coverage was quantified and normalized to NI area (Figure 4F). The iNOS failure threshold was defined as the Pt control sample with the highest normalized iNOS signal coverage (shown in Figure 4F as the dashed line). One out of the eleven Zn samples (9%), five out of the twelve binary samples (42%), three out of the eleven ternary samples (27%), and two out of the eleven quinary samples (19%) had iNOS values above the failure threshold.

Figure 4.

iNOS immunofluorescence labeling of A) Pt, B) Zn, C) Binary, D) Ternary, and E) Quinary containing implants at 6 months. The images represent the highest amount of iNOS signal for each material. In each image, the white dashed line outlines the neointima, “L” identifies the lumen of the artery, and “*” identifies the implant location. The white arrows point to auto-fluorescing corrosion product, which can be distinguished from the positive cells. All images were taken at 600X normal magnification. The scale bar is 100 μm. F) Box plot of positive iNOS coverage normalized to neointimal area. The horizontal dashed line represents the iNOS failure threshold. P values were obtained using an F test relative to the Pt control group. *p<0.05, **p<0.005

F-tests were performed to evaluate the variability of iNOS coverage for each material relative to the Pt control group (n = 8). Zn and the binary alloy had significantly higher variances than the platinum control group (p = 0.0128, n = 11 and p = 0.0013, n = 12, respectively). The ternary alloy followed a similar trend that was near statistical significance (p = 0.0541, n = 11). The quinary implant was the only group that did not have a variance either significantly higher or close to significance relative to the Pt control group (p = 0.3043, n = 11).

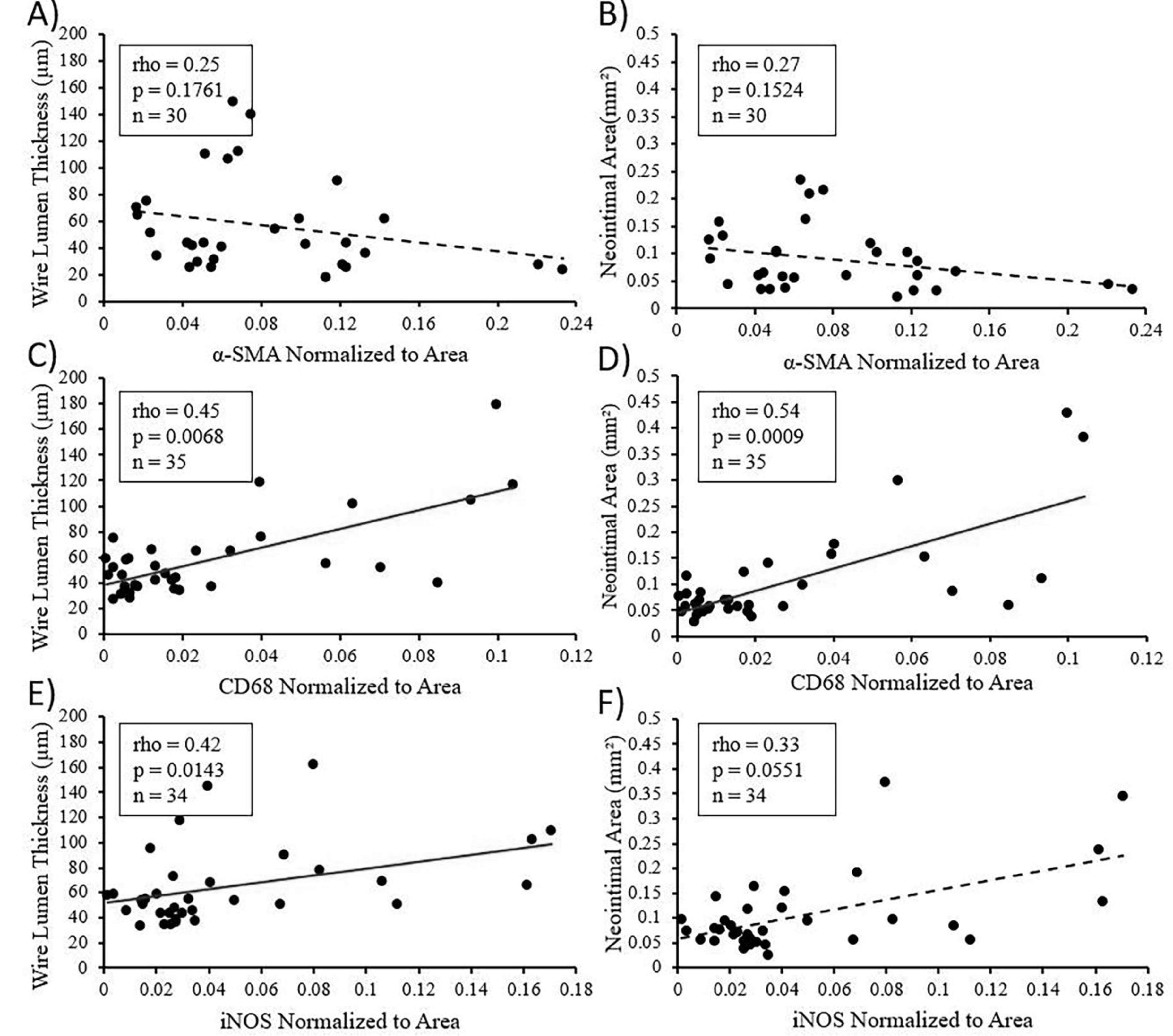

3.1.5. α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS Correlation to Neointimal Morphometrics

Spearman’s correlations were performed to assess the relationships between α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS with the two NI morphometrics WLT and NA for the three alloys evaluated (Figure 5). There was no significant correlation between α-SMA and either of the morphometrics, although there is a slight trend towards a negative correlation (rho = 0.25, p = 0.1761 for WLT and rho = 0.27, p = 0.1524 for NA, n = 30 for both). A significant positive correlation was found between CD68 and both NI morphometrics (rho = 0.45, p = 0.0068 for WLT, and rho = 0.54, p = 0.0009 for NA, n = 35 for both). iNOS had a similar relationship with the morphometrics, showing a significant positive correlation to WLT (rho = 0.42, p = 0.0143, and n = 34) and a strong positive trend for NA (rho = 0.33, p = 0.0551, and n = 34).

Figure 5.

Spearman’s correlations for the relationship between α-SMA and NI morphometrics WLT and NA (A and B, respectively), CD68 and WLT or NA (C and D, respectively), or iNOS and WLT or NA (E and F, respectively) in NIs surrounding the zinc alloys. A solid linear line of best fit represents a significant correlation (p < 0.05). A dashed line represents no significant correlation (p > 0.05)

3.2. In Vitro Results

3.2.1. Nitric Oxide Generation

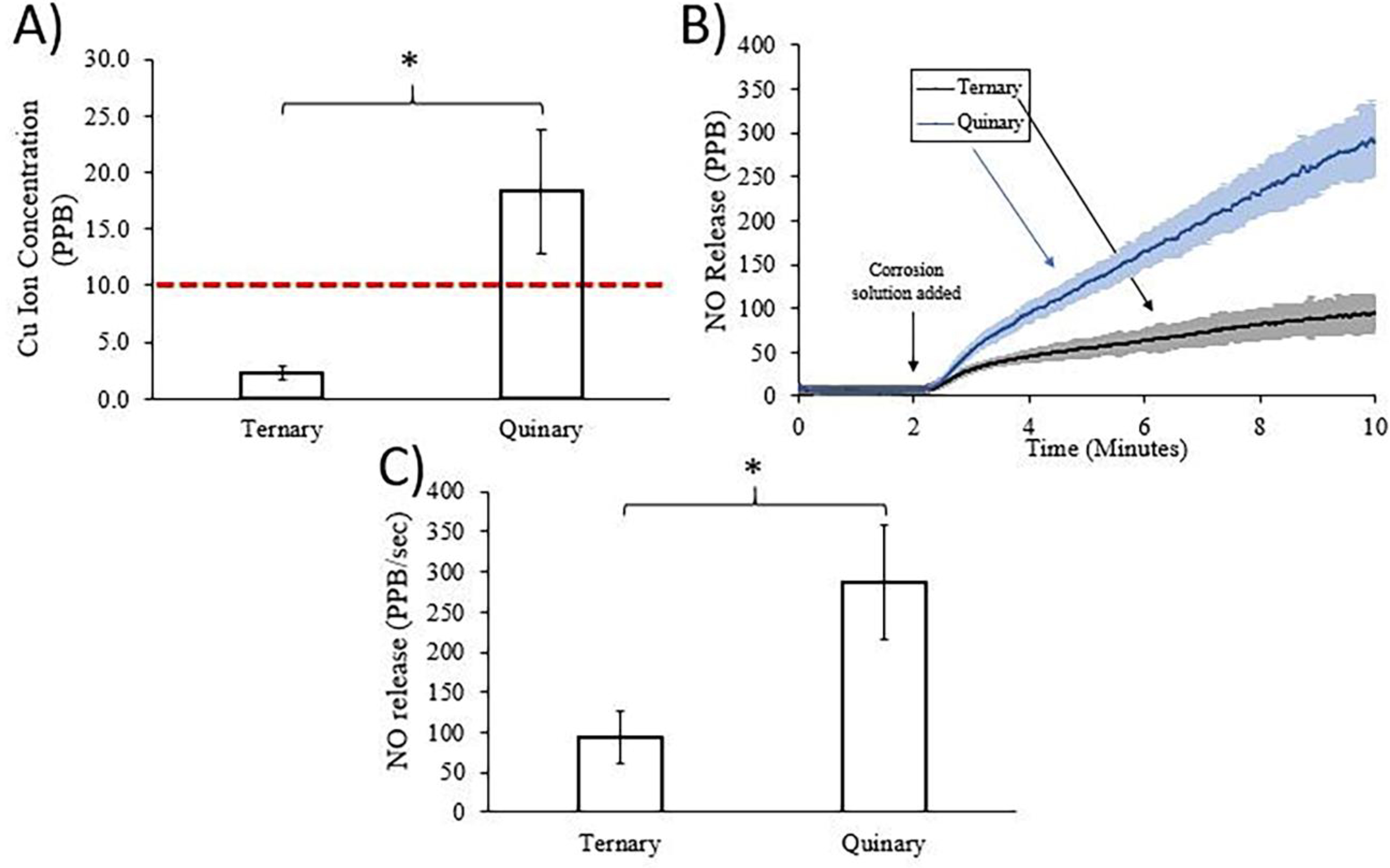

Ionic Cu is known to catalyze the release of NO from NO precursors that circulate in the blood31, 32. In order to investigate whether the Cu-containing quinary alloy may regulate inflammatory pathways by ionic Cu-dependent NO generation, in vitro corrosion experiments were conducted and corrosion extracts were analyzed for the presence of ionic Cu and their ability to generate NO. Figure 6A shows the ICP-OES analysis of the corrosion extracts. After 14 days of in vitro corrosion the quinary extracts contained detectable concentrations of ionic Cu, while ionic Cu was not detected in the ternary corrosion extracts. Although the ICP-OES results presented in Figure 6A show an ionic Cu concentration of ~2 PPB in the corrosion extracts from the ternary alloy, the detection limit of the ICP-OES system was 10 PPB. Ionic Cu is known to catalyze the generation of NO from RSNOs, which are continuously circulating and replenishing in the bloodstream33, 34. To determine if the presence of ionic Cu in the corrosion extracts could increase NO levels, the 14-day ternary and quinary alloy corrosion extracts were injected into 1 mM SNAP solutions and NO generation was measured using an NOA. As seen in Figure 6B, NO generation from the 1 mM SNAP solutions equilibrated to less than 10 PPB/sec for two minutes prior to the injection of the corrosion extracts. The addition of either ternary or quinary corrosion extract increased NO generation. However, significantly more NO was generated by the quinary extract (p = 0.0275, n = 3 for both groups) with final values at 2875 ± 72 PPB/sec vs. 94 ± 32 PPB/sec for the ternary alloy. The NO release from both extracts was averaged over the final 15 seconds of the experiment and compared, shown in Figure 6C.

Figure 6.

A) ICP-OES analysis of ionic copper concentration in corrosion solutions from ternary and quinary alloys after 14 days of immersion in hanks balanced salt solution. The horizontal dashed line represents the detection limit of the ICP-OES system. B) NO release over time from 1 mM SNAP solution by ternary and quinary corrosion solutions. Dark central lines represent the mean and the lighter surrounding regions represent the standard deviation (n = 3 for both groups). C) Average NO release over the last 15 seconds of the experiment from 1 mM SNAP solution by ternary and quinary corrosion solutions. Significance determined by a Welch’s t-test, *p < 0.05

4.0. Discussion

Over the past few years, binary Zn-Ag13, Zn-Ag-Mn16, and Zn-Cu-based alloys17, 18, 35–37 have generated interest for BRS applications due to their promising mechanical properties. In the present work, binary A4, ternary AM41, and quinary ACMZ4110 alloys were fabricated into wires and implanted into the abdominal rat aorta for bio-characterization and comparison to pure Zn and Pt controls. As was clearly shown by the H&E images in Figure 1, the NI formation surrounding the quinary implants were markedly smaller in size than for the binary and ternary implants, and similar to the Zn controls. This was our first evidence that the alloying additions included within the quinary alloy may improve the biological response.

To begin clarifying the mechanism, we characterized the presence and distribution of VSMCs and macrophages within the implant NIs. VSMCs are typically the dominant cell type within the NI of intravascular implants and are central to pathways leading to restenosis38. As expected, all the Zn-based materials exhibited a reduction in α-SMA coverage relative to Pt. This was not a surprise, as earlier works from our group39 and others3 have demonstrated a VSMC suppressive property for pure Zn implants. Following up on those early observations, we recently reported that ionic Zn suppresses VSMC neointimal hyperplasia by activating caspase-3 dependent apoptosis signaling pathways40. The present report demonstrates that the VSMC suppressive property of pure Zn arterial implants is retained following alloying to improve mechanical properties. This VSMC suppressive property is expected to decrease neointimal size and therefore improve the biocompatibility of Zn-based BRS materials.

Because failure at any location along the length of an intravascular stent restricts downstream blood flow, uniform NI growth with low variability in thickness is critical to the success of the implant. Since excessive inflammation is associated with neointimal growth and growth variability8, a high degree of inflammation should be avoided for stent materials. To evaluate the inflammatory properties of the zinc-based materials, CD68 and iNOS neointimal coverage was quantified and compared to platinum (conventional biostable control group) in terms of variability and failure. The quinary alloy was found to elicit a more favorable inflammatory response than the other zinc-bearing materials and was strikingly similar to the biostable control metal. As shown in Figure 3, 44% of the Zn samples, 50% of the binary samples, and 36% of the ternary samples experienced an increased CD68 coverage relative to the CD68 failure threshold. Surprisingly, all the quinary samples were below this threshold, performing better than pure Zn and similar to biostable/bioinert Pt. As shown by the immunofluorescence labeling of iNOS in Figure 4, 42% of the binary samples, 27% of the ternary samples, and 19% of the quinary samples experienced iNOS coverages above the iNOS failure threshold. The inflammatory responses of the evaluated alloys demonstrate an inflammation resistance property for the quinary alloy. This suggests that the inflammatory process mounted against a biodegradable stent made from the quinary alloy may be similar to that of conventional stent metals in terms of degree and variability.

The improved inflammatory response elicited by the quinary alloy could be attributed to multiple factors. The addition of Zr and Cu to the alloy will change the material microstructure and corrosion behavior. Changes to the corrosion rate and the composition of corrosion byproducts can influence the biological response. Indeed, we recently reported that pure Zn implants with different surface treatments that reduced the corrosion of pure Zn implants to different extents elicited markedly different biological responses23. Therefore, we speculate that the additions of Cu and Zr in the quinary alloy may alter the in vivo corrosion rate in a manner that reduces inflammation. It is also possible that the presence of Cu in the corrosion byproducts reduces the inflammatory response, as ionic Cu is known to catalyze the release of NO from RSNOs31, 32. Indeed, we confirmed the presence of ionic Cu in the quinary alloy corrosion extracts and the ability of these extracts to generate NO from RSNOs. RSNOs are NO donors that circulate in the blood and are constantly replenished to provide for the widespread physiological demand of NO31, 41. NO has many beneficial roles in the vascular system,42 including the inhibition of platelet adhesion43, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation44, 45, and leukocyte adhesion 46, 47. Therefore, we speculate that the inclusion of Cu in the quinary alloy may produce a sustained ionic Cu release that generates NO at the implant surface, ultimately shifting the inflammatory response in a more benign direction.

Although the quinary alloy evaluated here contained ~0.8% Cu by weight, the low concentration of ionic Cu present in the extracts was sufficient to nearly triple the NO generation compared to the reference material. Indeed, according to a recent report, ionic Zn can catalyze the generation of NO from SNAP, but at an order of magnitude below that of ionic Cu25. At low concentrations, NO is known to downregulate inflammation, whereas high concentrations of NO (produced by iNOS, for example) are known to upregulate inflammation48. The improved inflammatory response elicited by the quinary alloy may suggest that the NO generated from the alloy may be in the lower, therapeutic window. Although Zr4+ may also generate NO from synthetic RSNOs, the amount of NO generated by Cu2+ is over an order of magnitude greater than Zr4+ 49. This demonstrates that the Cu addition, rather than the presence of Zr in the corrosion extract, is responsible for the NO generation. Numerous reports have demonstrated that the inclusion of Cu into polymer coatings on blood contacting devices can promote NO generation at the surface of the material from RSNOs, ultimately improving device biocompatibility50–53. Here, we are the first to report that the inclusion of Cu into the bulk matrix of biodegradable Zn alloys may exert a similar therapeutic effect.

NI morphometrics such as NA and WLT are key indicators of application-relevant biocompatibility because they directly relate to the degree of arterial occlusion generated by the implant material11, 54–56. VSMC neointimal hyperplasia and chronic inflammation are the primary biological responses contributing to NI growth8. However, the relationship between these two processes and their mutual contribution to NI growth around Zn-based materials has not been clarified. To clarify this relationship, Spearman’s correlations were performed between α-SMA, CD68, and iNOS signal and WLT and NA for all the Zn alloys, as shown in Figure 5. The finding that α-SMA does not correlate with NI morphometrics, as the three experimental alloys suppress VSMC NI hyperplasia to a similar degree, suggests that the degree of VSMC NI hyperplasia is relatively consistent for Zn-bearing arterial implants. On the contrary, CD68 and iNOS both correlated significantly with NI morphometrics, demonstrating that the degree of chronic inflammation elicited by the implants ultimately determines NI size and therefore the success or failure of the implant. This important finding reinforces the importance of developing Zn-based implants with immune-resistant properties.

5.0. Conclusions

Following up on recent reports demonstrating the promising bioresorbable Zn-Ag, Zn-Ag-Mn, and Zn-Cu based materials, we aimed to evaluate the in vivo performance of these next generation Zn alloys. We successfully fabricated binary Zn-4Ag, ternary Zn-4Ag-0.6Mn, and quinary Zn-4Ag-0.8Cu-0.6Mn-0.15Zr alloys in implantable wire geometry. The three experimental alloys as well as pure Zn and Pt controls were implanted into the rat abdominal aorta for 6 months. Using standard histology and immuno-fluorescence techniques to comprehensively evaluate the cellular responses, we generated the following conclusions:

The quinary Cu-bearing alloy is the first zinc-based material featuring pronounced inflammation resistant properties relative to pure zinc.

VSMC suppression near the implant interface, first demonstrated for pure zinc implants, is retained in alloys of zinc.

Our correlation analyses demonstrate that the degree of inflammation against zinc-based arterial implants is a greater contributor to neointimal growth than smooth muscle cell hyperplasia

8.0. Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, grant #R15 HL 147299–01 and #1R01 HL 144739–01A1. A.A.O. was partially supported by the Michigan Space Grant Consortium, NASA grant #NNX15AJ20H. R.J.G. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Maria Kwesiga for her assistance with the NOA and Elisha Earley for preparing histological cross sections.

9.0. Abbreviations

- Zn

zinc

- Ag

silver

- Mn

manganese

- Cu

copper

- Zr

zirconium

- Pt

platinum

- BRS

bioresorbable stent

- NI

neointima/neointimal

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- iNOS

induced nitric oxide synthase

- α-SMA

alpha-smooth muscle actin

- DAPI

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride

- WLT

wire lumen thickness

- NA

neointimal area

- ICP-OES

inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy

- NO

nitric oxide

- SNAP

S-Nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine

- RSNO

S-nitrosothiol

- NOA

nitric oxide analyzer

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Bowen PK; Drelich J; Goldman J, Zinc exhibits ideal physiological corrosion behavior for bioabsorbable stents. Advanced materials 2013, 25 (18), 2577–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen PK; Shearier ER; Zhao S; Guillory RJ; Zhao F; Goldman J; Drelich JW, Biodegradable metals for cardiovascular stents: from clinical concerns to recent Zn-Alloys. Advanced healthcare materials 2016, 5 (10), 1121–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H; Wang C; Liu C; Chen H; Wu Y; Han J; Jia Z; Lin W; Zhang D; Li W, Evolution of the degradation mechanism of pure zinc stent in the one-year study of rabbit abdominal aorta model. Biomaterials 2017, 145, 92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hernández-Escobar D; Champagne S; Yilmazer H; Dikici B; Boehlert CJ; Hermawan H, Current status and perspectives of zinc-based absorbable alloys for biomedical applications. Acta biomaterialia 2019, 97, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katarivas Levy G; Goldman J; Aghion E, The prospects of zinc as a structural material for biodegradable implants—A review paper. Metals 2017, 7 (10), 402. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mostaed E; Sikora-Jasinska M; Drelich JW; Vedani M, Zinc-based alloys for degradable vascular stent applications. Acta biomaterialia 2018, 71, 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JM; Rodriguez A; Chang DT In Foreign body reaction to biomaterials, Seminars in immunology, Elsevier: 2008; pp 86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornowski R; Hong MK; Tio FO; Bramwell O; Wu H; Leon MB, In-stent restenosis: contributions of inflammatory responses and arterial injury to neointimal hyperplasia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1998, 31 (1), 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowen PK; Seitz JM; Guillory RJ; Braykovich JP; Zhao S; Goldman J; Drelich JW, Evaluation of wrought Zn-AI alloys (1, 3, and 5 wt% Al) through mechanical and in vivo testing for stent applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials 2018, 106 (1), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillory RJ; Bowen PK; Hopkins SP; Shearier ER; Earley EJ; Gillette AA; Aghion E; Bocks M; Drelich JW; Goldman J, Corrosion characteristics dictate the long-term inflammatory profile of degradable zinc arterial implants. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2016, 2 (12), 2355–2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillory RJ; Oliver AA; Davis EK; Earley EJ; Drelich JW; Goldman J, Preclinical In Vivo Evaluation and Screening of Zinc-Based Degradable Metals for Endovascular Stents. JOM 2019, 71 (4), 1436–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin H; Zhao S; Guillory R; Bowen PK; Yin Z; Griebel A; Schaffer J; Earley EJ; Goldman J; Drelich JW, Novel high-strength, low-alloys Zn-Mg (< 0.1 wt% Mg) and their arterial biodegradation. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2018, 84, 67–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikora-Jasinska M; Mostaed E; Mostaed A; Beanland R; Mantovani D; Vedani M, Fabrication, mechanical properties and in vitro degradation behavior of newly developed ZnAg alloys fo degradable implant applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2017, 77, 1170–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernousova S; Epple M, Silver as Antibacterial Agent: Ion, Nanoparticle, and Metal. Angew. Chem.-lnt. Edit. 2013, 52 (6), 1636–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanOosten SK; Yuca E; Karaca BT; Boone K; Snead ML; Spencer P; Tamerler C, Biosilver nanoparticle interface offers improved cell viability. Surface Innovations 2016, 4 (3), 121–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mostaed E; Sikora-Jasinska M; Ardakani MS; Mostaed A; Reaney IM; Goldman J; Drelich JW, Towards revealing key factors in mechanical instability of bioabsorbable Zn-based alloys for intended vascular stenting. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 105, 319–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mostaed E; Ardakani MS; Sikora-Jasinska M; Drelich JW, Precipitation induced room temperature superplasticity in Zn-Cu alloys. Materials Letters 2019, 244, 203–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Z; Niu J; Huang H; Zhang H; Pei J; Ou J; Yuan G, Potential biodegradable Zn-Cu binary alloys developed for cardiovascular implant applications. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials 2017, 72, 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CT; Zhou YH; Xu MC; Han PP; Chen L; Chang J; Xiao Y, Copper-containing mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds with multifunctional properties of angiogenesis capacity, osteostimulation and antibacterial activity. Biomaterials 2013, 34 (2), 422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou C; Li H-F; Yin Y-X; Shi Z-Z; Li T; Feng X-Y; Zhang J-W; Song C-X; Cui X-S; Xu K-L, Long-term in vivo study of biodegradable Zn-Cu stent: A 2-year implantation evaluation in porcine coronary artery. Acta biomaterialia 2019, 97, 657–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding Y; Wen C; Hodgson P; Li Y, Effects of alloying elements on the corrosion behavior and biocompatibility of biodegradable magnesium alloys: a review. Journal of materials chemistry B 2014, 2 (14), 1912–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahmi MWG; Trinanda AF; Pratiwi RY; Astutiningtyas S; Zakiyuddin A In The Effect of Zr Addition on Microstructures and Hardness Properties of Zn-Zr Alloys for Biodegradable Orthopaedic Implant Applications, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing: 2020; p 012065. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillory II RJ; Sikora-Jasinska M; Drelich JW; Goldman J, In Vitro Corrosion and In Vivo Response to Zinc Implants with Electropolished and Anodized Surfaces. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11 (22), 19884–19893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nisoli E; Clementi E; Paolucci C; Cozzi V; Tonello C; Sciorati C; Bracale R; Valerio A; Francolini M; Moncada S, Mitochondrial biogenesis in mammals: the role of endogenous nitric oxide. Science 2003, 299 (5608), 896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarthy CW; Guillory RJ; Goldman J; Frost MC, Transition-metal-mediated release of nitric oxide (NO) from S-nitroso-N-acetyl-d-penicillamine (SNAP): potential applications for endogenous release of NO at the surface of stents via corrosion products. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2016, 8 (16), 10128–10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghasemi A; Zahediasl S, Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism 2012. 110 (2), 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulford KAF; Sipos A; Cordell JL; Stross WP; Mason DY, Distribution of the CD68 macrophage/myeloid associated antigen. International Immunology 1990, 2 (10), 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown BN; Londono R; Tottey S; Zhang L; Kukla KA; Wolf MT; Daly KA; Reing JE; Badylak SF, Macrophage phenotype as a predictor of constructive remodeling following the implantation of biologically derived surgical mesh materials. Acta biomaterialia 2012, 8 (3), 978–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogdan C, Nitric oxide synthase in innate and adaptive immunity: an update. Trends in immunology 2015, 36 (3), 161–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantovani A; Sozzani S; Locati M; Allavena P; Sica A, Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends in Immunology 2002, 23 (11), 549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyn H aWilliams D, Identification of Cu+ as the effective reagent in nitric oxide formation from S-nitrosothiols (RSNO). Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 1996, (4), 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DLH, The chemistry of S-nitrosothiols. Accounts of chemical research 1999, 32 (10), 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster MW; Pawloski JR; Singel DJ; Stamler JS, Role of circulating S-nitrosothiols in control of blood pressure. Am Heart Assoc: 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagababu E; Rifkind JM, Routes for formation of S-nitrosothiols in blood. Cell biochemistry and biophysics 2013, 67 (2), 385–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niu J; Tang Z; Huang H; Pei J; Zhang H; Yuan G; Ding W, Research on a Zn-Cu alloy as a biodegradable material for potential vascular stents application. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2016, 69, 407–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yue R; Huang H; Ke G; Zhang H; Pei J; Xue G; Yuan G, Microstructure, mechanical properties and in vitro degradation behavior of novel Zn-Cu-Fe alloys. Materials Characterization 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Z; Huang H; Niu J; Zhang L; Zhang H; Pei J; Tan J; Yuan G, Design and characterizations of novel biodegradable Zn-Cu-Mg alloys for potential biodegradable implants. Materials & Design 2017, 117, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ip JH; Fuster V; Badimon L; Badimon J; Taubman MB; Chesebro JH, Syndromes of accelerated atherosclerosis: role of vascular injury and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1990, 15 (7), 1667–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowen PK; Guillory II RJ; Shearier ER; Seitz J-M; Drelich J; Bocks M; Zhao F; Goldman J, Metallic zinc exhibits optimal biocompatibility for bioabsorbable endovascular stents. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2015, 56, 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillory RJ II; Kolesar TM; Oliver A; Stuart JA; Bocks M; Drelich JW; Goldman J, Zn2+-dependent suppression of vascular smooth muscle intimal hyperplasia from biodegradable zinc implants. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 110826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loscalzo J; Welch G, Nitric oxide and its role in the cardiovascular system. Progress in cardiovascular diseases 1995, 38 (2), 87–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter AW; Schoenfisch MH, Nitric oxide release: Part II. Therapeutic applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2012, 41 (10), 3742–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freedman JE; Sauter R; Battinelli EM; Ault K; Knowles C; Huang PL; Loscalzo J, Deficient platelet-derived nitric oxide and enhanced hemostasis in mice lacking the NOSIII gene. Circulation research 1999, 84 (12), 1416–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garg UC; Hassid A, Nitric oxide-generating vasodilators and 8-bromo-cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibit mitogenesis and proliferation of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 1989, 83 (5), 1774–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ignarro LJ; Buga GM; Wei LH; Bauer PM; Wu G; del Soldato P, Role of the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98 (7), 4202–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubes P; Suzuki M; Granger D, Nitric oxide: an endogenous modulator of leukocyte adhesion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1991, 88 (11), 4651–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefer DJ; Jones SP; Girod WG; Baines A; Grisham MB; Cockrell AS; Huang PL; Scalia R, Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 1999, 276 (6), H1943–H1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guzik T; Korbut R; Adamek-Guzik T, Nitric oxide and superoxide in inflammation. Journal of physiology and pharmacology 2003, 54, 469–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutzke A; Melvin AC; Neufeld MJ; Allison CL; Reynolds MM, Nitric oxide generation from S-nitrosoglutathione: New activity of indium and a survey of metal ion effects. Nitric Oxide 2019, 84, 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frost MC; Reynolds MM; Meyerhoff ME, Polymers incorporating nitric oxide releasing/generating substances for improved biocompatibility of blood-contacting medical devices. Biomaterials 2005, 26 (14), 1685–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oh BK; Meyerhoff ME, Spontaneous catalytic generation of nitric oxide from S-nitrosothiols at the surface of polymer films doped with lipophilic copper (II) complex. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125 (32), 9552–9553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hwang S; Meyerhoff ME, Polyurethane with tethered copper (II)-cyclen complex: preparation, characterization and catalytic generation of nitric oxide from S-nitrosothiols. Biomaterials 2008, 29 (16), 2443–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo R; Liu Y; Yao H; Jiang L; Wang J; Weng Y; Zhao A; Huang N, Copper-incorporated collagen/catechol film for in situ generation of nitric oxide. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2015, 1 (9), 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joner M; Finn AV; Farb A; Mont EK; Kolodgie FD; Ladich E; Kutys R; Skorija K; Gold HK; Virmani R, Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006, 48 (1), 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murata A; Wallace-Bradley D; Tellez A; Alviar C; Aboodi M; Sheehy A; Coleman L; Perkins L; Nakazawa G; Mintz G, Accuracy of optical coherence tomography in the evaluation of neointimal coverage after stent implantation. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2010, 3 (1), 76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakazawa G; Finn AV; Vorpahl M; Ladich ER; Kolodgie FD; Virmani R, Coronary responses and differential mechanisms of late stent thrombosis attributed to first-generation sirolimus-and paclitaxel-eluting stents. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2011, 57 (4), 390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]