Abstract

Background

The anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibody introduces adaptable variations to the transcriptome and triggers tumor immune infiltration, resulting in colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment resistance. We intended to identify genes that play essential roles in cetuximab resistance and tumor immune cell infiltration.

Methods

A cetuximab-resistant CACO2 cellular model was established, and its transcriptome variations were detected by microarray. Meanwhile, public data from the Gene Expression Omnibus and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database were downloaded. Integrated bioinformatics analysis was applied to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the cetuximab-resistant and the cetuximab-sensitive groups. Then, we investigated correlations between DEGs and immune cell infiltration. The DEGs from bioinformatics analysis were further validated in vitro and in clinical samples.

Results

We identified 732 upregulated and 1259 downregulated DEGs in the induced cellular model. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment analyses, along with Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and Gene Set Variation Analysis, indicated the functions of the DEGs. Together with GSE59857 and GSE5841, 12 common DEGs (SATB-2, AKR1B10, ADH1A, ADH1C, MYB, ATP10B, CDX-2, FAR2, EPHB2, SLC26A3, ORP-1, VAV3) were identified and their predictive values of cetuximab treatment were validated in GSE56386. In online Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database, nine of twelve DEGs were recognized in the protein-protein (PPI) network. Based on the transcriptome profiles of CRC samples in TCGA and using Tumor Immune Estimation Resource Version 2.0, we bioinformatically determined that SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 expressions were associated with intensive infiltration of B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell and macrophage, which was then validated the correlation in clinical samples by immunohistochemistry. We found that SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were downregulated in vitro with cetuximab treatment. Clinically, patients with advanced CRC and high ORP-1 expression exhibited a longer progression-free survival time when they were treated with anti-EGFR therapy than those with low ORP-1 expression.

Conclusions

SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were related to cetuximab sensitivity as well as enhanced tumor immune cell infiltration in patients with CRC.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Drug resistance, Anti‐epidermal growth factor receptor therapy, Tumor immune cell infiltration, Transcriptional alterations

Background

In the United States, colorectal cancer (CRC) is estimated to be the third-most frequently occurring malignant tumor and third leading cause of cancer-related mortality, leading to the deaths of about 53,200 people in 2020 [1]. The incidence and mortality rates in 2015 were 37,000 cases and 19,000 deaths, with a 25- to 28-months overall survival time for Chinese patients suffering advanced CRC [2]. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab are effective therapeutics [3, 4] that shrink tumors for resectability [5–7] or relieve symptoms from unresectable masses by repressing tumor growth [8–10].

Mutations in the RAS family suggest continuous activation of EGFR downstream signaling [11–15] and RAS genes (KRAS, NRAS) are used as biomarkers to predict poor response to anti-EGFR therapy [16, 17]. However, tumor microenvironment re-plasticity, characterized by tumor immune cell infiltration and upregulation of immune checkpoint-related proteins, has recently been recognized as a novel explanation for drug resistance and treatment failure [18–20]. In particular, the interaction between tumor and immune microenvironment triggered by cetuximab or panitumumab in CRC accounts for immunogenic cell death and immune treatment resistance [21, 22].

In this study, we firstly performed high-throughput screening of transcriptomic alterations before and after induction cetuximab administration in a colon cancer cell model (CACO2). Then, we conducted integrated bioinformatics analysis of the transcriptome variations using public datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database to identify several core differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and investigated whether they were correlated with tumor immune cell infiltration. Finally, we validated the identified core DEGs in vitro and in clinical samples.

Methods

Cellular model and culture

Cell lines of human CRC (CACO2, HCT116, HT29, NCIH508, and RKO) were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling (Genetic Testing Biotechnology Corporation, Suzhou, China) and routinely tested for mycoplasma using MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza; LT07-218, Rockland, ME, USA). We established an EGFR antagonist-resistant cellular model using cetuximab sensitive cell line (CACO2-CS) and validated the transcriptional changes induced by cetuximab in the other cell lines. Using stepwise induction, we started with a low dose causing 50% cell growth inhibition (IC50). The dose was increased to 10 µg/mL after about two months, 50 µg/mL after another two months, and lastly 300 µg/mL. Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK8) (Dojindo, Shanghai, China) was used to test the cell viability. For colonies formation assay, cells were cultured in six-well plates with 1000 cells and 2 ml media including cetuximab (300 µg/ml) per well. After 14 days, colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Finally, the established cetuximab resistant cell line (CACO2-CR) was cultured with the maximal dose of cetuximab. CACO2-CS, HCT116, HT29, NCIH508, and RKO in the exponential growth phase were precultured in 12-well tissue culture plates for 24 h. Different concentrations of cetuximab (S20130004, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were added to cells which were incubated for 72 h (0 µg/mL and 25 µg/mL for CACO2, 0 µg/mL and 1 µg/mL for NCIH508, and 0 µg/mL and 50 µg/mL for HT29, HCT116, and RKO). CACO2-CS and CACO2-CR cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Paisley, UK) 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Paisley, UK). HT-29 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Paisley, UK), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Paisley, UK). HCT116 and NCIH508 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute Modified Medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Paisley, UK), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Paisley, USA). RKO cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 10 % FBS (Gibco, Paisley, UK), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Gibco, Paisley, UK). All cells were cultured in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. All cell lines experiments were repeated at least three times with three to six replicates.

Microarray screening for transcriptional variation after cetuximab induction

Total RNA was extracted and purified with the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Cat. # 217,004 QIAGEN GmBH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA integrity number was determined with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the RNA was amplified and labeled with the Low Input Quick Amp WT Labeling Kit (Cat. # 5190−2943, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Labeled cRNA was purified with the RNeasy mini kit (Cat. # 74,106). Samples were hybridized with about 1.65 µg Cy3-labeled cRNA by the Gene Expression Hybridization Kit (Cat. # 5188–5242, Agilent Technologies) in a hybridization oven (Cat. # G2545A, Agilent Technologies). After about 17 h, the slides were washed in staining dishes (Cat. # 121, Thermo Shandon, Waltham, MA, USA) with the Gene Expression Wash Buffer Kit (Cat. # 5188–5327, Agilent Technologies) and scanned by the Agilent Microarray Scanner (Cat. # G2565CA, Agilent Technologies). Data were retrieved with Feature Extraction software 10.7 (Agilent Technologies). Quantile normalization of the raw data was achieved by the limma package in R (version 3.4.1) [23].

Real-time quantitative PCR after cetuximab treatment in vitro

Total cellular RNA of cell lines treated with cetuximab was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) under the manufacturer’s instructions. Recombinant DNase I (Takara Bio, Beijing, China) was used to remove potential genomic DNA contamination. cDNA was generated with the PrimerScript™ RT master mix kit (Takara Bio, Dalian China). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of the identified DEGs was performed using the TB Green Premix Ex Taq™ kit (Takara Bio, Dalian China). All results were normalized to human GAPDH mRNA expression. The primers were listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The relative threshold cycle (Ct) method was used to display the results.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the cellular model

For the microarray screening of CACO2 cells treated with cetuximab, we visualized the principal component analysis (PCA) results using the R package ggbiplot (https://github.com/vqv/ggbiplot) after converting the raw signals into gene expression levels. We set thresholds of p < 0.05 and | log2 (fold change) | > 1 to identify significant DEGs using the limma package and created heat maps using the heatmap package.

Gene expression omnibus (GEO) microarray data and DEGs analysis

To further narrow down candidate DEGs in CRC under EGFR antagonist pressure, we downloaded three gene expression datasets including cell lines and clinical tissue sample data from GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). GSE59857 included the transcriptional and pharmacological profiles of 155 CRC cell lines. GSE5851 contained data from 80 clinical advanced CRC samples obtained before cetuximab monotherapy. GSE56386 contained data from eight primary CRC tumor tissue samples, comprising four from responders to cetuximab therapy and four from non-responders. From GSE59857, we downloaded the data for 20 cell lines, including 10 cetuximab-sensitive cases (OXCO2: GSM1448146, NCIH508: GSM1448142, DIFI: GSM1448175, COCM1: GSM1448167, CCK81: GSM1448097, C75: GSM1448201, HCA46: GSM1448177, C99: GSM1448204, HDC82: GSM1448128, and COGA1: GSM1448099) and 10 cetuximab-insensitive cases (SNU1047: GSM1448085, COLO320DM: GSM1448173, HUTU80: GSM1448180, KM12: GSM1448073, HDC143: GSM1448185, KM12SM: GSM1448188, KM12C: GSM1448186, COLO320: GSM1448152, KM12L4: GSM1448187, and C10: GSM1448196), among which HDC143 was deemed invalid and removed after analysis. We then converted the probe IDs into gene symbols using illuminaHumanv4.db. We retrieved the data for eight patients with the wild-type KRAS gene, including four responders to cetuximab treatment (GSM136609, GSM136593, GSM136654, and GSM136626) and four non-responders (GSM136635, GSM136646, GSM136607, and GSM136640) from GSE5851 and converted the probe IDs into gene symbols using the annotation library hgu133a2.db. The procedure for analyzing DEGs was the same as that for analyzing the CACO2 microarray data.

Gene Ontology (GO) term and Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses

For the enrichment analyses of the DEGs, a Metascape (https://metascape.org/) online analysis tool was used [24]. The parameters were set as the following: min overlap = 3, p-value cutoff = 0.01, and min enrichment = 1.5. Related terms were selected from the top 20, according to their p-values.

Gene sets Enrichment analysis (GSEA) and Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

GSEA was used to screen the biological states and processes associated with significantly upregulated or downregulated genes in the resistance group, with H.all.v7.1.symbols.gmt as the reference set [25]. The number of permutations was set to 1000. A p-value < 0.05 was considered indicative of significant enrichment. A normalized enrichment score was established to evaluate the degree of enrichment. GSVA was used to describe the enrichment degree of a biological state or process in a sample [26]. Enrichment scores were compared, and those meeting the standards of |log2 (fold change) | > 1 and p < 0.05 were considered significant results.

Construction of protein‐protein interaction (PPI) network

The PPIs of the central DEGs were generated using the STRING online database (https://string-db.org). To construct a PPI network, we retrieved cetuximab resistance candidates from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database (https://www.cancerrxgene.org) [27], confirmed their interactions using the STRING database [28], and finally visualized the result using Cystoscape [29].

Prediction of tumor immune cell infiltration

To investigate the relationship between hub DEG expression and tumor immune cell infiltration, the transcriptome landscapes of colonic or rectal adenocarcinoma samples (n = 177) in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database were analyzed using the online tool Tumor Immune Estimation Resource Version 2.0 (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) [30, 31].

Validation in clinical samples by immunohistochemistry staining

Patients with advanced CRC (n = 102) were diagnosed by pathological examination and administered systemic chemotherapeutics at Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University. Fifty-two patients received therapy containing cetuximab. The progression-free survival time (PFS) was recorded to evaluate the efficacy of cetuximab. Patients signed informed consent documents, and the ethics committee of Zhongshan Hospital approved the study.

Tumor samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, cut into sections of about 5 µm, and placed onto glass slides. After the samples were deparaffinized with xylene, hydrophilized, and unmasked, they were blocked with bovine serum albumin, immunostained with primary antibodies against SATB-2 (21307-1-AP, 1:100, Proteintech Group, Inc., Wuhan, China), ORP-1 (bs-17514R, 1:200, Bioss Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), MYB (bs-5978R, 1:200, Bioss Biological Technology Co., Ltd.), CDX-2 (bsm-33063m, 1:200, Bioss Biological Technology Co., Ltd.), CD8 (GB13068, 1:100, Servicebio Technology, Wuhan, China), CD19 (GB11061, 1:500, Servicebio Technology), CD4 (GB13064, 1:100, Servicebio Technology), and CD68 (GB13067-M-2, 1:100, Servicebio Technology) in a humidified environment at about 4 °C overnight and incubated with goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200) for about 30 min at about 20 °C. Subsequently, the slides were stained with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. Antigen–antibody complexes in the whole sample were detected using a panoramic slice scanner (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary), recorded in a file, and viewed using CaseViewer 2.2 (3DHISTECH). To evaluate gene expression in tissues, the following formula was used to calculate the H-score using Quant Center 2.1 (3DHISTECH): H-SCORE = ∑ (PI × I) = (percentage of cells of weak intensity × 1) + (percentage of cells of moderate intensity × 2) + percentage of cells of strong intensity × 3), where PI is the proportion of the positive signal pixel area and I is the coloring intensity.

Statistical analysis

Most statistical analyses were completed using bioinformatic tools mentioned above in R (version 3.4.1). The Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate method was utilized to adjust the p- values in screening DEGs from GEO profiles. Fisher’s exact test was employed to identify the significant GO terms and KEGG pathways. The correlation significance was examined by Spearman and Pearson correlation analyses. Differential expression levels of identified DEGs were assessed by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Kaplan - Meier survival curve and Log - rank test analysis was applied to investigated the predictive valued of identified DEGs for patients with CRC and receiving cetuximab contained therapy. The value of p < 0.050 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Model establishment and screening of DEGs

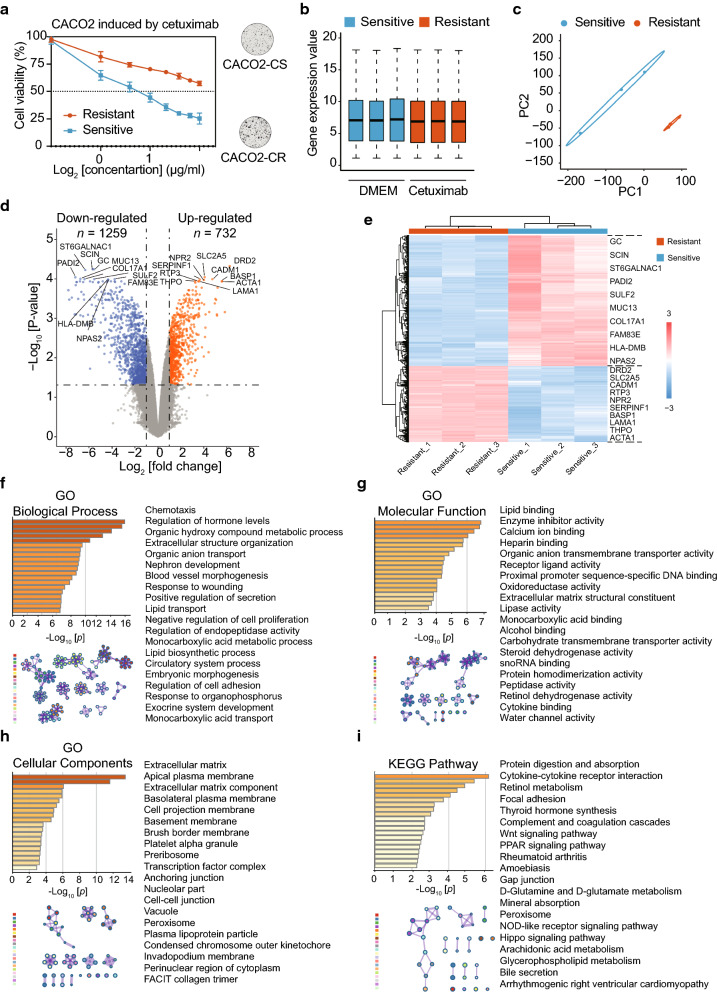

The study design is shown in Fig. 1. After the cetuximab resistant cellular model was established successfully (Fig. 2a), preprocessing of the raw data revealed a uniform distribution of DEGs between CACO2-CS and CACO2-CR (Fig. 2b). The PCA results had acceptable reproducibility (Fig. 2c). A total of 1991 DEGs were identified, with 732 upregulated genes and 1259 downregulated genes in CACO2-CR. These DEGs are shown in a volcano plot (Fig. 2d) and a heat map (Fig. 2e) and are listed in Table 1. In GO analysis, the most enriched GO terms determined by the cellular component function (CC) were “extracellular matrix,” “apical plasma membrane” and “extracellular matrix component” (Fig. 2h). KEGG signaling analysis suggested that the DEGs were considerably enriched in “protein digestion and absorption,” “cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction,” “retinol metabolism” shown in Fig. 2i and Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study

Fig. 2.

Identification and enrichment analysis of DEGs related to anti-EGFR antibody resistance in CACO2. a Establishment of a cetuximab-resistant CACO2 cell line (CACO2-CR) from its parental sensitive cell line (CACO2-CS) and validation of the resistance using cell viability tests. b Comparison of total gene expression between duplicate samples from the innate sensitive group (blue) and adaptive resistant (red) group. c Principal component analysis results suggested favorable reproducibility between the sensitive (blue) and resistant (red) groups. d The volcanic map reveals the distributions of downregulated (blue) and upregulated (orange) genes in the resistant group versus the sensitive group. Top 10 of DEGs between two groups were shown. e The heat map indicates the upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) DEGs between the sensitive (blue) and resistant (red) groups. Each column is a sample and each row is a gene. Top 10 of DEGs between two groups were shown. f GO biological process term enrichment analysis of DEGs (left) and their interrelationships (right). g GO molecular function term enrichment analysis of DEGs (left) and their interrelationships (right). h GO cellular component term enrichment analysis of DEGs (left) and their interrelationships (right). i KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs (left) and their interrelationships (right). DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. GO: Gene Ontology. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Table 1.

The expression of the top 20 upregulated and downregulated genes in the cetuximab resistant CACO2

| Gene symbol | Normalized Signal Value | Log [fold change] | P value | Adjustive p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive | Resistant | ||||||||

| Sam.1 | Sam.2 | Sam.3 | Sam.1 | Sam.2 | Sam.3 | ||||

| Top 20 of up-regulated genes | |||||||||

| DRD2 | 1.253 | 1.265 | 1.252 | 7.414 | 7.471 | 7.331 | 6.149 | 2.76E–09 | 5.19E–05 |

| SLC2A5 | 8.931 | 9.006 | 9.037 | 13.002 | 12.996 | 12.980 | 4.001 | 2.62E–08 | 9.87E–05 |

| CADM1 | 4.659 | 4.421 | 4.556 | 9.133 | 9.344 | 9.152 | 4.664 | 4.91E–08 | 1.11E–04 |

| RTP3 | 1.232 | 1.300 | 1.161 | 4.731 | 4.881 | 4.823 | 3.581 | 8.34E–08 | 1.14E–04 |

| NPR2 | 6.365 | 6.349 | 6.191 | 10.112 | 10.297 | 10.310 | 3.938 | 9.25E–08 | 1.16E–04 |

| SERPINF1 | 10.281 | 10.168 | 10.135 | 13.543 | 13.716 | 13.685 | 3.453 | 1.29E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| BASP1 | 6.890 | 6.446 | 6.407 | 11.922 | 12.156 | 12.069 | 5.468 | 1.33E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| LAMA1 | 6.237 | 6.392 | 6.334 | 9.733 | 9.873 | 9.949 | 3.531 | 1.42E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| THPO | 1.271 | 1.275 | 1.418 | 4.485 | 4.429 | 4.562 | 3.171 | 1.75E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| ACTA1 | 4.330 | 3.837 | 4.273 | 9.829 | 9.596 | 9.503 | 5.496 | 1.80E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| SERPINF2 | 11.096 | 11.257 | 10.992 | 14.287 | 14.346 | 14.294 | 3.194 | 2.59E–07 | 1.35E–04 |

| ANXA8 | 9.699 | 9.805 | 9.662 | 12.950 | 13.168 | 12.871 | 3.274 | 3.77E–07 | 1.73E–04 |

| DPYSL3 | 7.688 | 7.165 | 7.810 | 12.588 | 12.744 | 12.676 | 5.115 | 4.15E–07 | 1.82E–04 |

| PDGFRA | 1.312 | 1.304 | 1.231 | 5.091 | 5.216 | 4.782 | 3.748 | 4.25E–07 | 1.82E–04 |

| SDC2 | 4.645 | 4.510 | 4.744 | 7.533 | 7.547 | 7.725 | 2.968 | 5.37E–07 | 2.10E–04 |

| ORM1 | 12.007 | 12.089 | 11.909 | 14.634 | 14.613 | 14.758 | 2.667 | 5.43E–07 | 2.10E–04 |

| ORM2 | 12.062 | 12.209 | 12.006 | 14.728 | 14.646 | 14.739 | 2.612 | 5.85E–07 | 2.10E–04 |

| ADM | 10.696 | 10.620 | 10.518 | 13.201 | 13.321 | 13.175 | 2.621 | 5.92E–07 | 2.10E–04 |

| ADAM19 | 9.666 | 9.526 | 9.323 | 12.874 | 12.710 | 12.676 | 3.248 | 6.38E–07 | 2.22E–04 |

| CCDC3 | 9.139 | 9.112 | 8.781 | 12.448 | 12.206 | 12.351 | 3.324 | 9.05E–07 | 2.59E–04 |

| Top 20 of down-regulated genes | |||||||||

| GC | 6.719 | 6.693 | 6.902 | 1.271 | 1.278 | 1.263 | –5.500 | 8.90E–09 | 6.23E–05 |

| SCIN | 6.839 | 6.926 | 7.093 | 1.350 | 1.309 | 1.335 | –5.621 | 9.94E–09 | 6.23E–05 |

| ST6GALNAC1 | 7.759 | 7.546 | 7.389 | 1.269 | 1.309 | 1.356 | –6.253 | 1.39E–08 | 6.51E–05 |

| PADI2 | 8.533 | 8.655 | 8.104 | 1.339 | 1.256 | 1.373 | –7.108 | 3.18E–08 | 9.95E–05 |

| MUC13 | 14.179 | 13.905 | 14.478 | 7.486 | 7.521 | 7.534 | –6.674 | 4.05E–08 | 1.09E–04 |

| SULF2 | 9.285 | 8.985 | 9.273 | 3.737 | 3.522 | 3.850 | –5.478 | 5.92E–08 | 1.11E–04 |

| COL17A1 | 8.492 | 8.749 | 8.525 | 2.545 | 2.030 | 2.235 | –6.319 | 6.07E–08 | 1.11E–04 |

| FAM83E | 10.754 | 10.695 | 10.635 | 6.944 | 7.056 | 6.897 | –3.729 | 6.48E–08 | 1.11E–04 |

| HLA-DMB | 5.666 | 5.548 | 5.337 | 1.177 | 1.237 | 1.244 | –4.298 | 8.23E–08 | 1.14E–04 |

| NPAS2 | 5.506 | 5.310 | 5.640 | 1.250 | 1.186 | 1.173 | –4.282 | 8.47E–08 | 1.14E–04 |

| PNLIPRP2 | 9.009 | 8.923 | 8.898 | 4.505 | 4.836 | 4.560 | –4.310 | 1.04E–07 | 1.22E–04 |

| LCN2 | 11.287 | 11.659 | 11.027 | 4.564 | 4.442 | 4.834 | –6.711 | 1.24E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| SRPX | 9.803 | 9.612 | 9.507 | 5.937 | 5.942 | 5.842 | –3.734 | 1.53E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| HOXB9 | 10.762 | 10.582 | 10.682 | 7.503 | 7.485 | 7.573 | –3.155 | 1.66E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| BTNL3 | 5.120 | 5.170 | 5.485 | 1.188 | 1.231 | 1.215 | –4.047 | 1.77E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| TMC5 | 7.201 | 6.746 | 7.401 | 1.274 | 1.203 | 1.339 | –5.844 | 1.77E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| APOBEC1 | 6.060 | 5.632 | 6.092 | 1.210 | 1.170 | 1.156 | –4.749 | 1.78E–07 | 1.26E–04 |

| S100A9 | 10.469 | 10.404 | 9.896 | 3.540 | 3.948 | 3.972 | –6.436 | 2.00E–07 | 1.31E–04 |

| DDIT4L | 6.599 | 6.789 | 7.249 | 1.229 | 1.281 | 1.306 | –5.607 | 2.07E–07 | 1.31E–04 |

| PI3 | 13.824 | 13.941 | 13.611 | 9.571 | 9.226 | 9.378 | –4.400 | 2.12E–07 | 1.31E–04 |

Table 2.

GO term and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes

| Term | Description | Count | % | Log10 [p value] | Log10 [q value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Biological process | |||||

| GO:0006935 | Chemotaxis | 117 | 5.89 | −15.44 | −11.44 |

| GO:0010817 | Regulation of hormone levels | 102 | 5.13 | −15.05 | −11.33 |

| GO:1,901,615 | Organic hydroxy compound metabolic process | 100 | 5.03 | −13.61 | −10.01 |

| GO:0043062 | Extracellular structure organization | 82 | 4.13 | −12.37 | −8.87 |

| GO:0015711 | Organic anion transport | 85 | 4.28 | −10.60 | −7.25 |

| GO:0072006 | Nephron development | 37 | 1.86 | −9.56 | −6.40 |

| GO:0048514 | Blood vessel morphogenesis | 105 | 5.28 | −9.29 | −6.20 |

| GO:0009611 | Response to wounding | 105 | 5.28 | −9.25 | −6.20 |

| GO:0051047 | Positive regulation of secretion | 75 | 3.77 | −9.14 | −6.11 |

| GO:0006869 | Lipid transport | 66 | 3.32 | −9.03 | −6.06 |

| GO:0008285 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation | 113 | 5.69 | −8.91 | −6.01 |

| GO:0052548 | Regulation of endopeptidase activity | 73 | 3.67 | −8.70 | −5.86 |

| GO:0032787 | Monocarboxylic acid metabolic process | 97 | 4.88 | −8.15 | −5.36 |

| GO:0008610 | Lipid biosynthetic process | 103 | 5.18 | −7.83 | −5.11 |

| GO:0003013 | Circulatory system process | 83 | 4.18 | −7.17 | −4.54 |

| GO:0048598 | Embryonic morphogenesis | 87 | 4.38 | −6.84 | −4.26 |

| GO:0030155 | Regulation of cell adhesion | 99 | 4.98 | −6.68 | −4.14 |

| GO:0046683 | Response to organophosphorus | 31 | 1.56 | −6.68 | −4.14 |

| GO:0035272 | Exocrine system development | 17 | 0.86 | −6.62 | −4.11 |

| GO:0015718 | Monocarboxylic acid transport | 35 | 1.76 | −6.53 | −4.04 |

| GO molecular function | |||||

| GO:0008289 | Lipid binding | 104 | 5.23 | −6.90 | −3.45 |

| GO:0004857 | Enzyme inhibitor activity | 62 | 3.12 | −6.81 | −3.45 |

| GO:0005509 | Calcium ion binding | 97 | 4.88 | −6.45 | −3.37 |

| GO:0008201 | Heparin binding | 34 | 1.71 | −6.05 | −3.17 |

| GO:0008514 | Organic anion transmembrane transporter activity | 39 | 1.96 | −5.75 | −3.06 |

| GO:0048018 | Receptor ligand activity | 70 | 3.52 | −5.72 | −3.06 |

| GO:0000987 | Proximal promoter sequence-specific DNA binding | 84 | 4.23 | −5.16 | −2.65 |

| GO:0016491 | Oxidoreductase activity | 95 | 4.78 | −4.82 | −2.41 |

| GO:0005201 | Extracellular matrix structural constituent | 30 | 1.51 | −4.52 | −2.18 |

| GO:0016298 | Lipase activity | 25 | 1.26 | −4.46 | −2.16 |

| GO:0033293 | Monocarboxylic acid binding | 18 | 0.91 | −4.39 | −2.14 |

| GO:0043178 | Alcohol binding | 19 | 0.96 | −4.39 | −2.14 |

| GO:0015144 | Carbohydrate transmembrane transporter activity | 12 | 0.60 | −4.35 | −2.12 |

| GO:0033764 | Steroid dehydrogenase activity | 10 | 0.50 | −4.05 | −1.90 |

| GO:0030515 | snoRNA binding | 10 | 0.50 | −4.05 | −1.90 |

| GO:0042803 | Protein homodimerization activity | 81 | 4.08 | −4.04 | −1.90 |

| GO:0008233 | Peptidase activity | 78 | 3.93 | −3.82 | −1.73 |

| GO:0004745 | Retinol dehydrogenase activity | 8 | 0.40 | −3.80 | −1.73 |

| GO:0019955 | Cytokine binding | 24 | 1.21 | −3.69 | −1.63 |

| GO:0015250 | Water channel activity | 6 | 0.30 | −3.50 | −1.46 |

| GO cellular component | |||||

| GO:0031012 | Extracellular matrix | 98 | 4.93 | −13.46 | −10.17 |

| GO:0016324 | Apical plasma membrane | 68 | 3.42 | −11.60 | −8.79 |

| GO:0044420 | Extracellular matrix component | 17 | 0.86 | −6.08 | −3.57 |

| GO:0016323 | Basolateral plasma membrane | 41 | 2.06 | −5.91 | −3.52 |

| GO:0031253 | Cell projection membrane | 56 | 2.82 | −5.90 | −3.52 |

| GO:0005604 | Basement membrane | 23 | 1.16 | −5.55 | −3.21 |

| GO:0031526 | Brush border membrane | 16 | 0.81 | −5.25 | −2.97 |

| GO:0031091 | Platelet alpha granule | 21 | 1.06 | −4.93 | −2.72 |

| GO:0030684 | Pre-ribosome | 19 | 0.96 | −4.87 | −2.70 |

| GO:0005667 | Transcription factor complex | 53 | 2.67 | −4.60 | −2.46 |

| GO:0070161 | Anchoring junction | 71 | 3.57 | −3.64 | −1.68 |

| GO:0044452 | Nucleolar part | 29 | 1.46 | −3.61 | −1.67 |

| GO:0005911 | Cell-cell junction | 53 | 2.67 | −3.49 | −1.60 |

| GO:0005773 | Vacuole | 93 | 4.68 | −3.40 | −1.56 |

| GO:0005777 | Peroxisome | 24 | 1.21 | −3.40 | −1.56 |

| GO:0034358 | Plasma lipoprotein particle | 10 | 0.50 | −3.32 | −1.52 |

| GO:0000940 | Condensed chromosome outer kinetochore | 6 | 0.30 | −3.29 | −1.52 |

| GO:0071438 | Invadopodium membrane | 4 | 0.20 | −3.22 | −1.48 |

| GO:0048471 | Perinuclear region of cytoplasm | 85 | 4.28 | −3.20 | −1.47 |

| GO:0005593 | FACIT collagen trimer | 4 | 0.20 | −2.88 | −1.25 |

| KEGG pathway | |||||

| hsa04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 23 | 1.16 | −6.16 | −3.46 |

| hsa04060 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 45 | 2.26 | −5.38 | −2.98 |

| hsa00830 | Retinol metabolism | 17 | 0.86 | −4.86 | −2.64 |

| hsa04510 | Focal adhesion | 34 | 1.71 | −4.45 | −2.36 |

| hsa04918 | Thyroid hormone synthesis | 17 | 0.86 | −4.08 | −2.08 |

| hsa04610 | Complement and coagulation cascades | 17 | 0.86 | −3.71 | −1.85 |

| hsa04310 | Wnt signaling pathway | 24 | 1.21 | −3.21 | −1.49 |

| hsa03320 | PPAR signaling pathway | 15 | 0.75 | −3.18 | −1.49 |

| hsa05323 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 17 | 0.86 | −3.02 | −1.36 |

| hsa05146 | Amoebiasis | 17 | 0.86 | −2.70 | −1.27 |

| hsa04540 | Gap junction | 16 | 0.81 | −2.69 | −1.27 |

| hsa00471 | D-Glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism | 3 | 0.15 | −2.68 | −1.27 |

| hsa04978 | Mineral absorption | 11 | 0.55 | −2.60 | −1.21 |

| hsa04146 | Peroxisome | 15 | 0.75 | −2.53 | −1.16 |

| hsa04621 | NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 25 | 1.26 | −2.49 | −1.14 |

| hsa04390 | Hippo signaling pathway | 23 | 1.16 | −2.42 | −1.13 |

| hsa00590 | Arachidonic acid metabolism | 12 | 0.60 | −2.38 | −1.13 |

| hsa00564 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 16 | 0.81 | −2.35 | −1.12 |

| hsa04976 | Bile secretion | 13 | 0.65 | −2.32 | −1.10 |

| hsa05412 | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy | 13 | 0.65 | −2.26 | −1.06 |

GO, Gene Ontology. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

Gene set enrichment

GSEA and GSVA of the DEGs (Tables 3 and 4, respectively) indicated that the downregulated genes were enriched in “HALLMARK_COMPLEMENT” (Fig. 3a), “HALLMARK_BILE_ACID_METABOLISM” (Fig. 3b), “HALLMARK_IL2_STATS_SIGNALING” (Fig. 3c), “HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_DN” (Fig. 3d), “HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY” (Fig. 3e), “HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS” (Fig. 3f), “HALLMARK_INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE” (Fig. 3g), and “HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_LATE” (Fig. 3h). The upregulated genes were enriched in “HALLMARK_PEROXISOME” (Fig. 3i). The GSVA results suggested that the downregulated genes were enriched in “HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 and V2” and upregulated genes were enriched in “HALLMARK_MYOGENESIS,” “HALLMARK_ANGIOGE-NESIS,” “HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE,” and “HALLMARK_TGF_ BETA_SIGNALING” (Fig. 3j).

Table 3.

Gene set enrichment analysis of upregulated and downregulated gene sets in the cetuximab resistant group

| Name | Size | Es | Nes | Non p value | FDR q value | FWER p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation in Resistant Group | ||||||||||

| HALLMARK_PEROXISOME | 19 | −0.36 | −1.32 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.39 | ||||

| HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_UP | 24 | −0.17 | −1.00 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_MYOGENESIS | 38 | −0.48 | −0.93 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_DN | 27 | −0.24 | −0.92 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_ADIPOGENESIS | 24 | −0.17 | −0.80 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE | 31 | −0.21 | −0.77 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 24 | −0.28 | −0.76 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_P53_PATHWAY | 24 | −0.14 | −0.68 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 1.00 | ||||

| Down-regulation in Resistant Group | ||||||||||

| HALLMARK_COMPLEMENT | 30 | 0.34 | 1.59 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.09 | ||||

| HALLMARK_BILE_ACID_METABOLISM | 21 | 0.38 | 1.57 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.19 | ||||

| HALLMARK_IL2_STAT5_SIGNALING | 31 | 0.38 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.25 | ||||

| HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_DN | 24 | 0.42 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.25 | ||||

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY | 39 | 0.30 | 1.43 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ||||

| HALLMARK_HYPOXIA | 38 | 0.30 | 1.41 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.25 | ||||

| HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS | 30 | 0.28 | 1.35 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.43 | ||||

| HALLMARK_INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE | 29 | 0.44 | 1.29 | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.56 | ||||

| HALLMARK_GLYCOLYSIS | 16 | 0.39 | 1.22 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.56 | ||||

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_LATE | 34 | 0.40 | 1.21 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.56 | ||||

| HALLMARK_XENOBIOTIC_METABOLISM | 30 | 0.25 | 1.20 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.62 | ||||

| HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_UP | 41 | 0.48 | 1.13 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.67 | ||||

| HALLMARK_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB | 30 | 0.32 | 1.13 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.67 | ||||

| HALLMARK_HEME_METABOLISM | 21 | 0.29 | 1.08 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.95 | ||||

| HALLMARK_APICAL_JUNCTION | 26 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.44 | 0.88 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_COAGULATION | 30 | 0.26 | 0.99 | 0.45 | 0.85 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | 19 | 0.40 | 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS | 21 | 0.37 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_MITOTIC_SPINDLE | 15 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 | 21 | 0.37 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION | 17 | 0.32 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 44 | 0.29 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 0.80 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_IL6_JAK_STAT3_SIGNALING | 16 | 0.27 | 0.87 | 0.53 | 0.84 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION | 22 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.89 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_MTORC1_SIGNALING | 19 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 0.96 | 1.00 | ||||

| HALLMARK_FATTY_ACID_METABOLISM | 31 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 1.00 | ||||

Table 4.

Gene set variation analysis of upregulated and downregulated gene sets in the cetuximab resistant group

| HALLMARK GENE SETS | Log [FC] | p value | Adjustive p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HALLMARK_MYOGENESIS | 1.058 | 2.34E−05 | 3.89E−04 |

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 1.115 | 3.21E−05 | 3.89E−04 |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 | −1.096 | 3.89E−05 | 3.89E−04 |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V2 | −1.134 | 2.88E−05 | 3.89E−04 |

| HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS | 1.229 | 1.43E−05 | 3.89E−04 |

| HALLMARK_TGF_BETA_SIGNALING | 1.078 | 9.87E−05 | 6.17E−04 |

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE | 0.909 | 9.74E−05 | 6.17E−04 |

| HALLMARK_UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE | −0.978 | 7.86E−05 | 6.17E−04 |

| HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS | −0.915 | 2.91E−04 | 1.45E−03 |

| HALLMARK_EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 0.741 | 2.72E−04 | 1.45E−03 |

| HALLMARK_APICAL_JUNCTION | 0.820 | 3.21E−04 | 1.46E−03 |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | −0.926 | 7.41E−04 | 3.09E−03 |

| HALLMARK_APOPTOSIS | 0.574 | 1.13E−03 | 4.13E−03 |

| HALLMARK_HEME_METABOLISM | 0.610 | 1.16E−03 | 4.13E−03 |

| HALLMARK_KRAS_SIGNALING_UP | −0.622 | 1.24E−03 | 4.13E−03 |

| HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY | 0.572 | 1.41E−03 | 4.16E−03 |

| HALLMARK_PEROXISOME | 0.676 | 1.38E−03 | 4.16E−03 |

| HALLMARK_UV_RESPONSE_DN | 0.624 | 1.95E−03 | 5.42E−03 |

| HALLMARK_HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING | 0.742 | 1.96E−02 | 4.97E−02 |

| HALLMARK_OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION | −0.599 | 2.09E−02 | 4.97E−02 |

| HALLMARK_REACTIVE_OXYGEN_SPECIES_PATHWAY | 0.706 | 2.03E−02 | 4.97E−02 |

Fig. 3.

GSEA and GSVA of DEGs. a-h GSEA of downregulated and (i) upregulated DEGs involved in biological states and processes in the resistant group, compared with those in the sensitive group. j Volcanic diagram of the GSVA results for the DEGs, which were enriched in the resistant group or the sensitive group (highlighted orange points and blue points, respectively). DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. GSEA: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. GSVA: Gene Set Variation Analysis

Common DEGs and PPI network construction

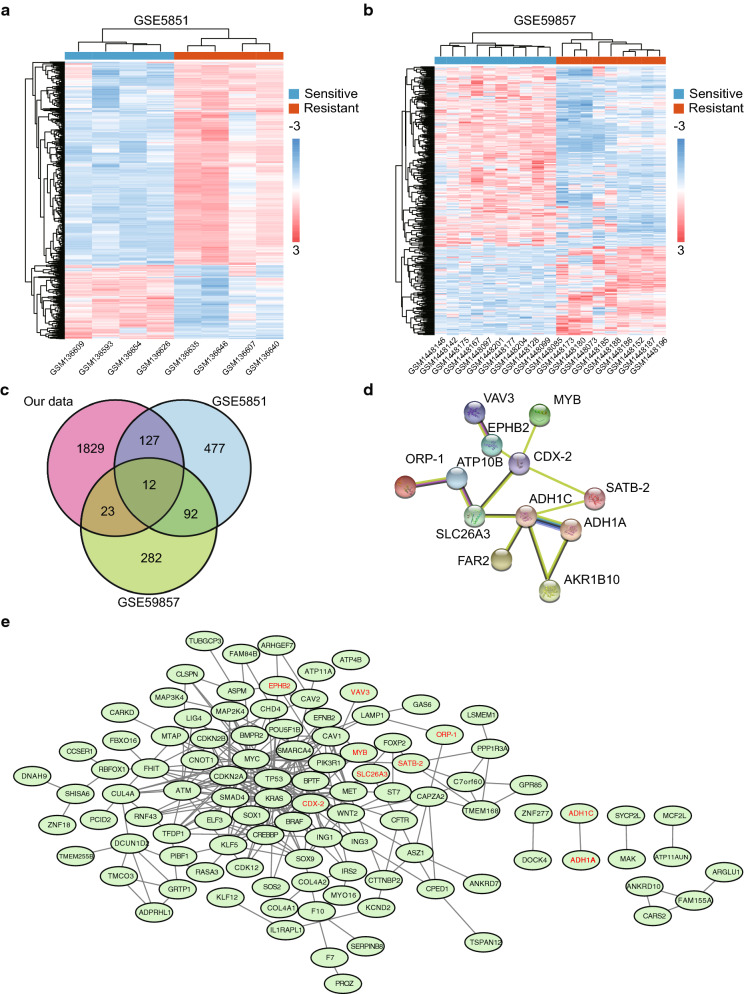

We identified 708 (Fig. 4a) and 298 (Fig. 4b) DEGs in GSE5851 and GSE59857, respectively. After integrating the DEGs from our own screenings with those from the two GEO datasets, 12 common DEGs were identified (Fig. 4c). These DEGs did not represent any protein-level interactions (Fig. 4d). Then, we combined recognized cetuximab resistance-related genes from the GDSC database (Table 5) with the 12 common DEGs and constructed a PPI network (Fig. 4e). The following six core DEGs were identified: SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, CDX-2, SLC26A3, and EPHB2. Consequently, we selected the GSE56386 dataset to validate the variations in the expression levels of the 12 DEGs between cetuximab responders and non-responders in clinical terms. SATB-2, MYB, CDX-2, SLC26A3, and FAR2 were downregulated (Fig. 5a, c–e, g) and AKR1B10 was upregulated in the non-responder group (Fig. 5l). Although a trend of downregulation was observed in the other six genes (Fig. 5b, f, h–k), they exhibited no significant differences between two groups, possibly owing to the small sample size. These 12 genes had an optimal prediction accuracy in GSE56386. The receiver operating characteristic curves for the 12 genes are presented in Additional file 2: Fig. S1.

Fig. 4.

Identification of common DEGs and construction of PPI network. a, b Identification of DEGs between the resistant (red) and sensitive (blue) groups from the GSE5851 and GSE59857 datasets, illustrated by a heat map. Each column is a sample and each row is a gene. c The venn diagram shows the intersection of DEGs among GSE5851, GSE59857 and CACO2-CR cellular model. d The Network diagram illustrates the interactions of common DEGs. e The PPI network including 12 DEGs and recognized cetuximab resistance-related genes from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. PPI: protein-protein interaction network

Table 5.

Cetuximab resistance-related genes from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database

| Cancer feature | Effect size | p value | FDR% | No. of altered cell lines | Tissue analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRGAP3_mut | −1.310 | 0.0382 | 99.7 | 3 | COREAD |

| PBRM1_mut | −0.971 | 0.0791 | 99.7 | 4 | COREAD |

| B2M_mut | −0.722 | 0.0879 | 99.7 | 7 | COREAD |

| FBXW7_mut | −0.575 | 0.0998 | 99.7 | 13 | COREAD |

| BRAF_mut | 0.580 | 0.109 | 99.7 | 10 | COREAD |

| cnaCOREAD47 | 0.737 | 0.111 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

| cnaCOREAD18 | 0.611 | 0.124 | 99.7 | 8 | COREAD |

| MGA_mut | −0.688 | 0.132 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

| cnaCOREAD14 | 0.892 | 0.147 | 99.7 | 3 | COREAD |

| CTCF_mut | −0.560 | 0.17 | 99.7 | 7 | COREAD |

| cnaCOREAD37 | 0.634 | 0.172 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

| CDH1_mut | −0.819 | 0.195 | 99.7 | 3 | COREAD |

| CTNNB1_mut | −0.577 | 0.199 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

| CREBBP_mut | 0.530 | 0.213 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

| CHD9_mut | −0.468 | 0.231 | 99.7 | 9 | COREAD |

| BRWD1_mut | −0.740 | 0.231 | 99.7 | 3 | COREAD |

| CHD4_mut | 0.518 | 0.285 | 99.7 | 3 | COREAD |

| APC_mut | −0.285 | 0.313 | 99.7 | 31 | COREAD |

| AKAP9_mut | −0.412 | 0.316 | 99.7 | 8 | COREAD |

| cnaCOREAD32 | −0.372 | 0.347 | 99.7 | 6 | COREAD |

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the expression levels of core DEGs in GSE56386. a SATB-2, c MYB, d CDX-2, e SLC26A3, and g FAR2 were significantly downregulated and (l)AKR1B10 was apparently upregulated among cetuximab non-responders compared with cetuximab responders. No significant differences were seen in (b)ORP-1, f EPHB2, h VAV3, i ATP10B, j ADH1A, k ADH1C. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes

Core DEGs and tumor immune cell infiltration

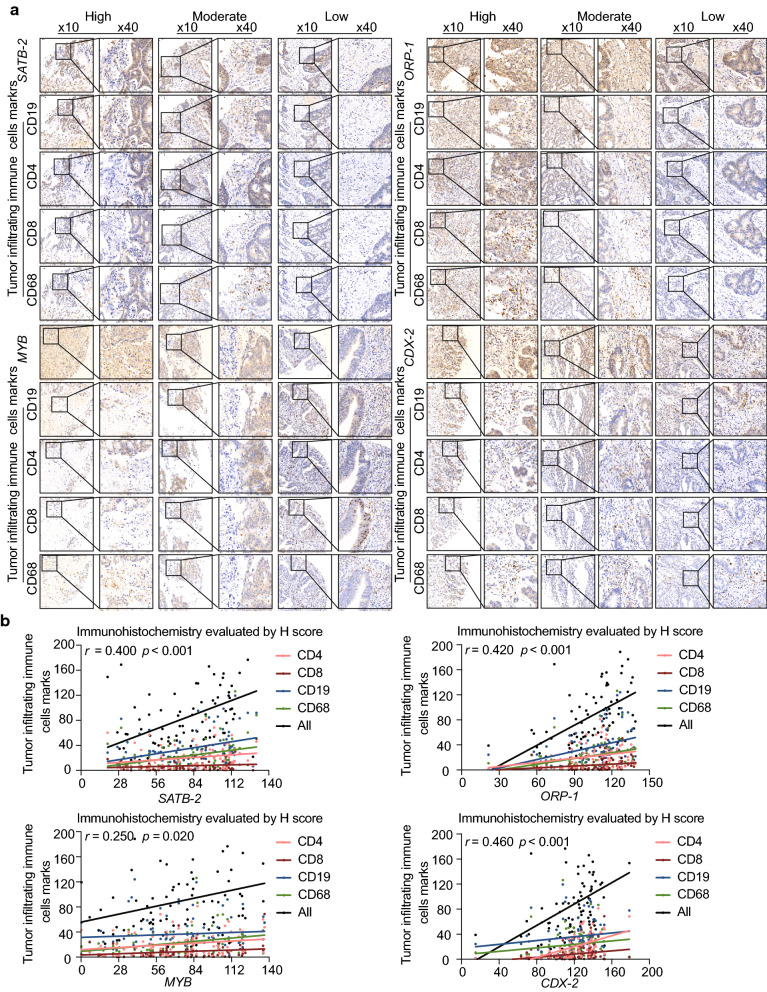

We observed significant correlations between the expression levels of the core DEGs SATB-2 (Fig. 6a), ORP-1 (Fig. 6b), MYB (Fig. 6c), and CDX-2 (Fig. 6d) and tumor immune cell infiltration represented by the expression of B cell, CD4+ T cell, CD8+ T cell, and macrophage markers in TCGA. Immunohistochemical staining of a tissue microarray containing 102 CRC clinical samples (Fig. 7a) demonstrated that the expression of these four genes was positively associated with tumor-infiltrating immune cell markers such as CD4, CD8, CD19, and CD68 (Fig. 7b; Table 6).

Fig. 6.

Association between the expression level of common DEGs and immune cell infiltration. The relationship between expression levels of (a) SATB-2, (b) ORP-1, (c) MYB, and (d) CDX-2 and tumor purity, infiltrating B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and macrophages was investigated by the online tool Tumor Immune Estimation Resource Version. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. TIMER: Tumor Immune Estimation Resource Version

Fig. 7.

Relationship between core DEGs and tumor-infiltrating immune cell markers in CRC. a The representative immunohistochemical staining images of SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, CDX-2, CD19, CD4, CD8, and CD68. b Spearman analysis results indicated that core DEGs were positively associated with tumor-infiltrating immune cell markers. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. CRC: Colorectal cancer

Table 6.

Spearman correlation analysis of differentially expressed genes and tumor-infiltrating immune cell markers in clinical samples

| Tumor-infiltrating immune cells marks | Gene expression level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman correlation | 95% CI | p value | |

| SATB- | |||

| CD4 | 0.22 | 0.00 to 0.42 | 0.047 |

| CD8 | 0.15 | -0.07 to 0.35 | 0.184 |

| CD19 | 0.36 | 0.16 to 0.54 | < 0.001 |

| CD68 | 0.34 | 0.14 to 0.52 | 0.002 |

| CD4 and CD8 | 0.22 | 0.07 to 0.42 | 0.044 |

| CD4, CD8, CD19, CD68 | 0.40 | 0.20 to 0.57 | < 0.001 |

| ORP-1 | |||

| CD4 | 0.28 | 0.07 to 0.46 | 0.010 |

| CD8 | 0.24 | 0.03 to 0.43 | 0.030 |

| CD19 | 0.36 | 0.16 to 0.53 | < 0.001 |

| CD68 | 0.31 | 0.11 to 0.50 | 0.003 |

| CD4 and CD8 | 0.29 | 0.08 to 0.48 | 0.007 |

| CD4, CD8, CD19, CD68 | 0.42 | 0.23 to 0.58 | < 0.001 |

| MYB | |||

| CD4 | 0.22 | 0.01 to 0.42 | 0.040 |

| CD8 | 0.20 | -0.01 to 0.40 | 0.070 |

| CD19 | 0.09 | -0.13 to 0.30 | 0.450 |

| CD68 | 0.28 | 0.07 to 0.47 | 0.009 |

| CD4 and CD8 | 0.26 | 0.05 to 0.45 | 0.020 |

| CD4, CD8, CD19, CD68 | 0.25 | 0.04 to 0.44 | 0.020 |

| CDX-2 | |||

| CD4 | 0.66 | 0.52 to 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| CD8 | 0.35 | 0.14 to 0.53 | 0.001 |

| CD19 | 0.20 | -0.02 to 0.40 | 0.070 |

| CD68 | 0.23 | 0.01 to 0.43 | 0.030 |

| CD4 and CD8 | 0.65 | 0.50 to 0.76 | < 0.001 |

| CD4, CD8, CD19, CD68 | 0.46 | 0.27 to 0.62 | < 0.001 |

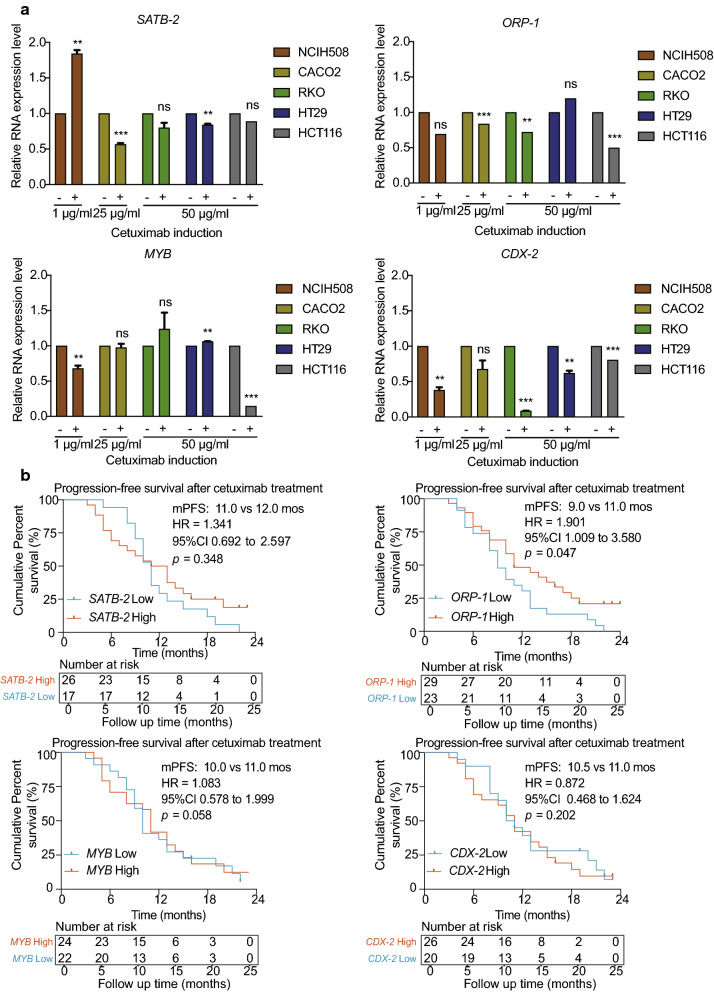

Exploring the expression of identified core DEGs in vitro

We conducted preliminary experiments in several CRC cell lines and detected that ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were downregulated in NCIH508wtRAS/RAF (a cell line sensitive to cetuximab), while SATB-2 expression decreased in CACO2 wtRAS/RAF (a cell line partially sensitive to cetuximab) and HT29 wtRAS/mtRAF (a cell line resistant to cetuximab) at the half-maximal inhibition concentration of cetuximab. A reduction in ORP-1 and CDX-2 expression was observed in most of these cell lines regardless of RAS and RAF status (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8.

Exploring the expression of core DEGs in vitro and their prognostic roles in CRC. a SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were downregulated after cetuximab treatment. b Patients with high expression levels of core DEGs in primary tumors exhibited a tendency to experience a longer progression-free survival time. **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001, ns, p > 0.05. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. CRC: Colorectal cancer

The roles of identified core DEGs in clinical samples with anti-EGFR therapy

The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients were recorded and are shown in Additional file 3: Table S2. Median follow-up time was 33.1 months (interquartile range, 17.2 to 52.5 months). Compared with patients with low ORP-1 expression, those with high ORP-1 expression in CRC experienced a significantly longer PFS time (median times were 9.0 months and 11.0 months, respectively, hazard rate [HR] = 1.901, p = 0.047) after administration of chemotherapeutics containing cetuximab (Fig. 8b).

Discussion

Alterations in genes that function in the epidermal growth factor (EGF) signaling pathway, such as increases in EGFR copy number, amplification of ERBB family, overexpression of IGF1 or VEGF, or novel mutations such as point mutations in RAS, BRAF, PI3KCA, or MEK in the EGFR extracellular domain or in the downstream pathway, result in EGFR antagonist resistance. Recently, disturbances in the tumor microenvironment caused by EGFR antibody have also been recognized as factors in treatment failure. Garvey et al. reported that cetuximab causes cancer-associated fibroblasts to secrete more EGF and reactivate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in para-CRC cells [32]. Critically, it is important to understand the interaction between tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment in anti-EGFR therapy resistance.

We conducted an integrated bioinformatic analysis to identify nine common DEGs between the cetuximab sensitive and resistant groups combining high-throughput data of the cetuximab resistant cell line model and data of cell lines and clinical samples from GEO profiles. The relationship between DEGs identified in our study and tumor immune cell infiltration was evaluated in TCGA and validated in clinical samples from our hospital. We found that four (SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2) of nine DEGs were associated with infiltrated T cells, B cells, and macrophages in CRC. The decreasing trend of expression levels of ORP-1, MYB and CDX-2 under cetuximab pressure was observed in vitro (Additional file 4: Fig. S2), which was consistent with the expression changes in the established cetuximab resistant cell line (CACO2-CR). Moreover, patients with high expression levels of these genes, especially ORP-1, exhibited prolonged survival receiving anti-EGFR therapy.

SATB-2 encodes a DNA binding protein and mediates transcription regulation as well as chromatin remodeling. SATB-2 attenuates the activity of MEK5/ERK5 and suppresses tumorigenesis and metastasis [33]. The upregulation of SATB-2 via DNA demethylation of the promoter region and H3K4me3 increases TH1-type chemokine expression and immune cell density in CRC [34]. ORP-1, as a member of the oxysterol-binding protein family involve in human innate immune system, binds to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate by interacting with RAB7A and stabilizing GTP-RAB7A and regulates the MHC class I -mediated antigen processing and presentation pathway [35, 36]. In addition, ORP-1 suppresses tumorigenesis via metabolism-associated pathway [37]. MYB is a protein-encoding oncogene that functions as a transcriptional activator. Paradoxically, patients with CRC and high MYB expression exhibit low incidence of distant metastases [38] and favorable clinical prognosis [39]. Millen et al. demonstrated that a high level of CD8+ tumor immune infiltrating cells and a clinical history of longer relapse-free survival were related to high expression of MYB. An immunomodulatory effect conferred by MYB was also observed in CD8+ TILs in the murine CRC model [40]. CDX-2 encodes a regulator of intestine-specific genes involved in cell growth and differentiation. CDX-2 is downregulated in the invasive part of tumor tissues and is associated with tumor-stroma protein expression as well as inflammatory cytokine release in CRC [41]. Low levels of CDX-2 expression indicate a particularly poor survival prognosis, especially in patients with tumors that have a high stromal content [42].

Zanella et al. reported that EGFR antagonists inhibit colorectal tumor growth and simultaneously protect the tumor from inhibition by transcriptional regulation [43]. Woolston et al. supported this finding and revealed that cetuximab prompts a transformation from a mutational variation to a mesenchymal transition representative of tumor-associated fibroblast enrichment [20]. It seems that cetuximab evokes immune inflammation via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity but paradoxically weakens this effect via a form of IgG1 antibody-mediated immunogenic cell death [21] while upregulating immunosuppressive TGF-β expression in CRC [44]. In fact, in a stage Ib/II trial of combined cetuximab and pembrolizumab treatment for patients with advanced CRC, the combination treatment of cetuximab with pembrolizumab significantly increased the density of CD3+, CD8+, and CTLA-4+ lymphocytes and natural killer cells in tumors. In the peripheral blood, the overall density of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes decrease, especially that of the PD1+ memory T cells [45, 46]. In the process of acquiring secondary resistance, the tumor might experience the transition from the immune-inflamed phenotype to the immune-desert phenotype, which features by key target genes involved in tumor immune cell infiltration [47–49]. We believed that the core DEGs identified in this study, SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2, might play critical roles in the transition.

Nevertheless, there were some limitations lying in this study. As models of anti-EGFR antibody resistance are not easy to established, only one cellular model was established and screened in the study. More cetuximab resistant cellular models with wild-type RAS and RAF genotypes are required to be established for validation. The DEGs identified using in silico methods should be further validated in vitro and in vivo. The results drawn from the retrospective clinical cohort with a small sample size also need further verification in a larger population. The specific immune cell types involved in secondary anti-EGFR antibody resistance should be more clearly elucidated.

Conclusions

In summary, we distinguished cetuximab-induced DEGs associated with variations of tumor immune cell infiltration in CRC by establishing a cetuximab resistant cellular model and integrated bioinformatics analysis. The results suggested that transcriptomic alterations and immune landscape remodeling should receive additional scrutiny during anti-EGFR antibody treatment. Furthermore, immunotherapy could be considered in the early stages of cetuximab treatment rather than after resistance has already occurred.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Sequences of primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. ROC curves for the cetuximab sensitivity of the 12 DEGs in GSE56386. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Clinicopathological data of patients with colorectal cancer in the tissue microarray.

Additional file 4: Figure S2. SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were downregulated in the resistant CACO2. ##, p < 0.01, ###, p < 0.001.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GSEA

Gene Sets Enrichment Analysis

- GSVA

Gene Set Variation Analysis

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- GDSC

Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- OSBP

Oxysterol-binding protein

- TILs

Tumor immune infiltrating cells

- COAD

Colon adenocarcinoma

- READ

Rectum adenocarcinoma

Authors’ contributions

TL: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, resources. YC: methodology, software, resources. LL: data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation. ML: investigation, validation, visualization, writing— review & editing. XS, YY, KP and KR: data curation, writing—review & editing. YY and YC: project administration, writing—reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Zhongshan Hospital (No. 2019ZSYQ21), CSCO-Youth Innovation Research Fund (Y-young2019-057), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81602038, 81772511 and 81900482). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Public datasets of colon adenocarcinoma and rectum adenocarcinoma analyzed during the current study can be retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/. GSE5851, GSE56368, and GSE59857 datasets can be retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University approved this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Li Liang and Mengling Liu equally contributed to this work

Contributor Information

Yanjie Chen, Email: chen.yanjie@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Tianshu Liu, Email: liu.tianshu@zs-hospital.sh.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12935-021-01829-8.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmuller C, Kahl C, Seipelt G, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):1065–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avallone A, Budillon A. Impact of subsequent therapies on outcome of the FIRE-3/AIO KRK0306 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primrose J, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Valle J, O’Reilly D, Siriwardena A, Hornbuckle J, Peterson M, Rees M, Iveson T, et al. Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis: the New EPOC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):601–11. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levi FA, Boige V, Hebbar M, Smith D, Lepere C, Focan C, Karaboue A, Guimbaud R, Carvalho C, Tumolo S, et al. Conversion to resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer with hepatic artery infusion of combined chemotherapy and systemic cetuximab in multicenter trial OPTILIV. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(2):267–74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridgewater JA, Pugh SA, Maishman T, Eminton Z, Mellor J, Whitehead A, Stanton L, Radford M, Corkhill A, Griffiths GO, et al. Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis (New EPOC): long-term results of a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):398–411. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30798-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garattini S, Torri V, Floriani I. Cetuximab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Meyerhardt JA, Schrag D, Greene C, O’Neil BH, Atkins JN, et al. Effect of first-line chemotherapy combined with cetuximab or bevacizumab on overall survival in patients with KRAS wild-type advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2392–401. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adam R, Aloia T, Levi F, Wicherts DA, de Haas RJ, Paule B, Bralet MP, Bouchahda M, Machover D, Ducreux M, et al. Hepatic resection after rescue cetuximab treatment for colorectal liver metastases previously refractory to conventional systemic therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(29):4593–602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bregni G, Sciallero S, Sobrero A. HER2 amplification and anti-EGFR sensitivity in advanced colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(5):605–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.7229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waddell T. Targeting EGFR in colorectal cancer: beyond KRAS exon 2. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(6):540–1. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz LA, Jr, Williams RT, Wu J, Kinde I, Hecht JR, Berlin J, Allen B, Bozic I, Reiter JG, Nowak MA, et al. The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR blockade in colorectal cancers. Nature. 2012;486(7404):537–40. doi: 10.1038/nature11219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin IH, Oktay AA. EGFR signalling and oncogenic pathway signature in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62(11):1670. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachiglio AM, Lambiase M, Fenizia F, Roma C, Cardone C, Iannaccone A, De Luca A, Carotenuto M, Frezzetti D, Martinelli E, et al. Genomic profiling of KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer patients reveals novel mutations in genes potentially associated with resistance to anti-EGFR agents. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(6):859. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, Humblet Y, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Jassem J, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(11):1023–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Rowland A, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Karapetis CS. Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(1):13–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertotti A, Papp E, Jones S, Adleff V, Anagnostou V, Lupo B, Sausen M, Phallen J, Hruban CA, Tokheim C, et al. The genomic landscape of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nature. 2015;526(7572):263–267. doi: 10.1038/nature14969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S, Bardelli A. Resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: from heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(11):1269–80. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolston A, Khan K, Cunningham D, Gerlinger M. Genomic and transcriptomic determinants of therapy resistance and immune landscape evolution during anti-EGFR treatment in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(1):35–50 e39. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pozzi C, Cuomo A, Spadoni I, Magni E, Silvola A, Conte A, Sigismund S, Ravenda PS, Bonaldi T, Zampino MG, et al. The EGFR-specific antibody cetuximab combined with chemotherapy triggers immunogenic cell death. Nat Med. 2016;22(6):624–31. doi: 10.1038/nm.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giordano GR, Porras A, Pancione AM. Immune resistance and EGFR antagonists in colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(8):1089. doi: 10.3390/cancers11081089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C, Chanda SK. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(23):3251–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira MR, Santos GA, Biagi CA, Silva Junior WA, Zambuzzi WF. GSVA score reveals molecular signatures from transcriptomes for biomaterials comparison. J Biomed Mater Res A 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Yang W, Soares J, Greninger P, Edelman EJ, Lightfoot H, Forbes S, Bindal N, Beare D, Smith JA, Thompson IR, et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D955–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otasek D, Morris JH, Boucas J, Pico AR, Demchak B. Cytoscape automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1758-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(W1):W509–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garvey CM, Lau R, Sanchez A, Sun RX, Fong EJ, Doche ME, Chen O, Jusuf A, Lenz HJ, Larson B, et al. Anti-EGFR therapy induces EGF secretion by cancer-associated fibroblasts to confer colorectal cancer chemoresistance. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6):1393. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mansour MA, Hyodo T, Ito S, Kurita K, Kokuryo T, Uehara K, Nagino M, Takahashi M, Hamaguchi M, Senga T. SATB2 suppresses the progression of colorectal cancer cells via inactivation of MEK5/ERK5 signaling. FEBS J. 2015;282(8):1394–1405. doi: 10.1111/febs.13227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu M, Xu X, Pan B, Chen X, Lin K, Zeng K, Liu X, Xu T, Sun L, Qin J, et al. LncRNA SATB2-AS1 inhibits tumor metastasis and affects the tumor immune cell microenvironment in colorectal cancer by regulating SATB2. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1063-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson M, Lehto M, Tanhuanpaa K, Cover TL, Olkkonen VM. The oxysterol-binding protein homologue ORP1L interacts with Rab7 and alters functional properties of late endocytic compartments. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(12):5480–92. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-03-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suchanek M, Hynynen R, Wohlfahrt G, Lehto M, Johansson M, Saarinen H, Radzikowska A, Thiele C, Olkkonen VM. The mammalian oxysterol-binding protein-related proteins (ORPs) bind 25-hydroxycholesterol in an evolutionarily conserved pocket. Biochem J. 2007;405(3):473–80. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motazacker MM, Pirhonen J, van Capelleveen JC, Weber-Boyvat M, Kuivenhoven JA, Shah S, Hovingh GK, Metso J, Li S, Ikonen E, et al. A loss-of-function variant in OSBPL1A predisposes to low plasma HDL cholesterol levels and impaired cholesterol efflux capacity. Atherosclerosis. 2016;249:140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tichy M, Knopfova L, Jarkovsky J, Pekarcikova L, Veverkova L, Vlcek P, Katolicka J, Capov I, Hermanova M, Smarda J, et al. Overexpression of c-Myb is associated with suppression of distant metastases in colorectal carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(8):10723–9. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4956-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tichy M, Knopfova L, Jarkovsky J, Vlcek P, Katolicka J, Capov I, Hermanova M, Smarda J, Benes P. High c-Myb expression associates with good prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10(6):1393–7. doi: 10.7150/jca.29530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millen R, Malaterre J, Cross RS, Carpinteri S, Desai J, Tran B, Darcy P, Gibbs P, Sieber O, Zeps N, et al. Immunomodulation by MYB is associated with tumor relapse in patients with early stage colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(7):e1149667. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1149667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsen J, Espersen ML, Jess P, Kirkeby LT, Troelsen JT. The clinical perspectives of CDX2 expression in colorectal cancer: a qualitative systematic review. Surg Oncol. 2014;23(3):167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandberg TP, Sweere I, van Pelt GW, Putter H, Vermeulen L, Kuppen PJ, Tollenaar R, Mesker WE. Prognostic value of low CDX2 expression in colorectal cancers with a high stromal content—a short report. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2019;42(3):397–403. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanella ER, Galimi F, Sassi F, Migliardi G, Cottino F, Leto SM, Lupo B, Erriquez J, Isella C, Comoglio PM, et al. IGF2 is an actionable target that identifies a distinct subpopulation of colorectal cancer patients with marginal response to anti-EGFR therapies. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(272):272ra212. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tauriello DVF, Palomo-Ponce S, Stork D, Berenguer-Llergo A, Badia-Ramentol J, Iglesias M, Sevillano M, Ibiza S, Canellas A, Hernando-Momblona X, et al. TGFbeta drives immune evasion in genetically reconstituted colon cancer metastasis. Nature. 2018;554(7693):538–543. doi: 10.1038/nature25492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boland PM, Ma WW. Immunotherapy for colorectal cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9(5):50. doi: 10.3390/cancers9050050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le DT, Kim TW, Van Cutsem E, Geva R, Jager D, Hara H, Burge M, O’Neil B, Kavan P, Yoshino T, et al. Phase II open-label study of pembrolizumab in treatment-refractory, microsatellite instability-high/mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer: KEYNOTE-164. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):11–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue Y, Hazama S, Suzuki N, Tokumitsu Y, Kanekiyo S, Tomochika S, Tsunedomi R, Tokuhisa Y, Iida M, Sakamoto K, et al. Cetuximab strongly enhances immune cell infiltration into liver metastatic sites in colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(3):455–460. doi: 10.1111/cas.13162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Wei Y, Fang W, Lu C, Chen J, Cui G, Diao H. Cetuximab enhanced the cytotoxic activity of immune cells during treatment of colorectal cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(3):1038–50. doi: 10.1159/000485404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sunakawa Y, Yang D, Cao S, Zhang W, Moran M, Astrow SH, Hsiang J, Stephens C, Tsuji A, Takahashi T, et al. Immune-related genes to dominate Neutrophil-lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) associated with survival of cetuximab treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17(4):e741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Sequences of primers used for real-time quantitative PCR.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. ROC curves for the cetuximab sensitivity of the 12 DEGs in GSE56386. DEGs: Differentially expressed genes. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Clinicopathological data of patients with colorectal cancer in the tissue microarray.

Additional file 4: Figure S2. SATB-2, ORP-1, MYB, and CDX-2 were downregulated in the resistant CACO2. ##, p < 0.01, ###, p < 0.001.

Data Availability Statement

Public datasets of colon adenocarcinoma and rectum adenocarcinoma analyzed during the current study can be retrieved from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/. GSE5851, GSE56368, and GSE59857 datasets can be retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.