Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco control research and advocacy has yet to capitalize on understanding the tobacco industry supply chain. The objective of this narrative review is to expose the processes, actors and supporting industries involved in tobacco production, laying the groundwork to expand the scope of tobacco control beyond the transnational tobacco companies (TTCs).

METHODS

We reviewed 69 academic articles (2013 to 2019) and five tobacco industry journal issues.

RESULTS

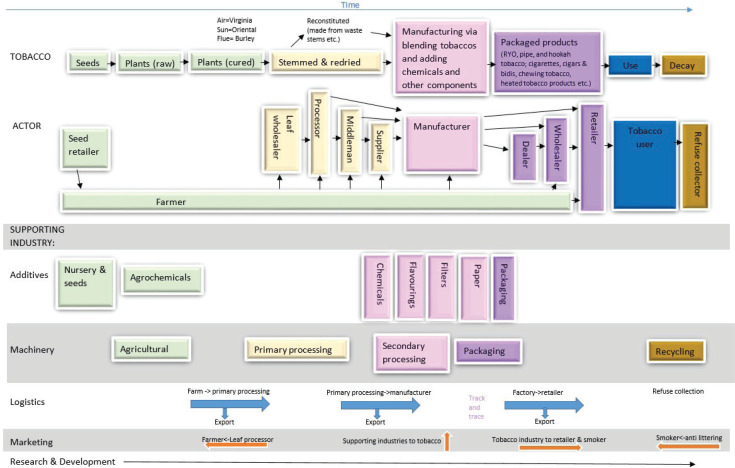

We identify six major processes in tobacco production: farming, primary processing of the leaf, secondary processing into products such as cigarettes, packaged product, usage by smokers, and decay. Supply chain actors include seed and plant retailers, farmers, leaf processors, wholesalers, brokers and middlemen, manufacturers, retailers, smokers and refuse collectors with considerable variation in intermediate actors by location. Supporting industries supply additives, machinery, packaging, logistics, marketing, and research and development (R&D).

CONCLUSIONS

This expanded understanding of the supply chain can enable wider appreciation of the various incentives and risks of being involved in the industry, all of which is important information to feed into tobacco control policies. Researchers and campaigners, seeking to design effective policy preventing the expansion of this industry and the health harms it produces, need to look beyond the TTCs to identify under-exploited leverage points along the entire tobacco supply chain.

Keywords: tobacco industry, supply chain, tobacco farming, transnational, manufacturing, production

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) defines the tobacco industry as ‘tobacco manufacturers, wholesale distributors and importers of tobacco products’1. Most tobacco control research remains focused on the four transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) due to their global economic power2-4. However, this focus misses most of the actors involved in bringing tobacco from field to smoker. If these actors did not work in synchrony with TTCs then TTCs would not have such profitable supply chains5,6. Here we produce a narrative review to introduce these opaque aspects of the tobacco industry using supply chain mapping.

Supply chain mapping is common in the academic literature on global commodity chains7, global value chains8 and global production networks9 . Likewise, civil society, for example non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and activist groups, has used supply chain mapping to understand the impacts of companies’ business activities, otherwise obscured through a lack of transparency10. The contribution of supply chain mapping to efforts to understand industry impacts, hold companies to account for these impacts, and foster transparency and accountability is increasingly recognised11.

The objective of this study is to set an expanded supply chain agenda in order to provide insights into new potential avenues of work for tobacco control researchers and advocates, deepening as well as how profit and power is accrued and distributed among participants, our understanding of the reach of the tobacco industry into other sectors and occupations. The tobacco supply chain is complex and involves many processes, products, and actors not always associated with tobacco production. Identifying these complexities is an important step in designing future research, campaigns, and regulation aimed at controlling these activities.

METHODS

Academic literature in SCOPUS (extracted 23 April 2019) and Web of Science (extracted 19 July 2019) was searched using the terms: ‘supply chain’ AND ‘(tobacco OR ciga*)’. After excluding duplicates and articles prior to 2013, there were 69 articles reviewed. These included articles funded by the tobacco industry. We did not use these industry-funded articles for statistics or arguments that might be unreliable, but simply to identify actors and processes not widely available in tobacco research to date (i.e. this is a deliberate strategy to fill some missing gaps). This review was augmented by a review of advertisements and articles in tobacco industry journals in 2019 (Tobacco International: 4 issues, and Tobacco Journal International: 1 issue). Supplementary internet searches and a priori knowledge of supply chains were used to find further sources and aid understanding. In total, we found 230 contributors to the supply chain.

RESULTS

The tobacco supply chain can be understood in terms of its processes, the actors directly involved in production, and supporting industries. Figure 1 presents a visual overview of the tobacco industry in its entirety, laying the initial groundwork for future work in this area.

Figure 1.

The Tobacco Supply Chain

Processes

Tobacco exists as seeds, plants, cut tobacco, tobacco products, and refuse. The tobacco supply chain transforms tobacco through six major processes: farming, primary processing of the leaf, secondary processing into products such as cigarettes, product packaging, usage by smokers and decay. TTCs may directly own some elements and buy in components and expertise for others – the balance changes over time12. In some countries, parts of the supply chain are state-owned13.

Actors

Actors include seed and plant retailers, farmers, leaf processors, wholesalers, brokers and middlemen, manufacturers, retailers, smokers and refuse collectors (the last being funded through taxation or occasionally by tobacco companies if extended producer responsibility schemes are in place)14.

Farmers can purchase seeds or seedlings from retailers15,16. Tobacco can be grown in TTC or leaf company owned estates or by smallholder farmers17. Smallholders can hold contracts with a TTC or leaf company, where firms are contracted to buy the entire crop (although the price is not guaranteed18 making farmers’ profits volatile19), as well as provide agricultural guidance and inputs, usually via loans, such as seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides, as well as transport to the next stage of the supply chain16,18-21. Such integrated production systems and incentives encourage farmers to choose to grow tobacco rather than other crops20.

Wholesalers acquire tobacco from the farmers either by contract or by auction, which they then either store in warehouses or export immediately21. Sometimes, primary processing is carried out by the wholesale leaf companies, other times by companies that also manufacture cigarettes; again tobacco can be exported at this stage20.

Supply chain intermediaries vary by place. In Java, for example, middlemen acquire primary processed tobacco and sell it on to ‘suppliers’22. In other parts of Indonesia and in India, brokers often buy tobacco from local collectors5,15,22 who then sell it on to major tobacco companies. These differences matter as closed and complex trading systems offer ample opportunity for parties to take advantage of farmers5. In other contexts, tobacco supply chains are more integrated and a single company may own not only the primary and secondary processing factories, but also the transport and storage facilities between them20.

Manufacturers create and package tobacco products such as cigarettes, chewing tobacco, cigars, pipe tobacco, roll-your-own tobacco and snuff21. To give a sense of the scale of these operations, in 2014, six trillion cigarette sticks were manufactured across 500 factories globally23.

The organization of intermediaries operating between manufacturers and retailers also varies by place. In China, for example, the manufacturer deals directly with retail24. In Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal, smokeless tobacco manufacturers supply ‘dealers’ who then deliver to wholesale retailers25. These wholesalers procure and sell products to vendors or retailers25 together with non-tobacco products21. Retailers sell the product to smokers25. Typically they include supermarkets, small grocers, convenience stores, and specialist tobacconists21.

Smokers are, of course, the end-product consumers, but they are not the final actors. Often forgotten are the refuse collectors disposing of tobacco products26. This is a significant externality of the supply chain and tobacco companies have mostly avoided being held responsible for these costs27.

Supporting industries

Supporting industries supply additives, machinery, logistics, marketing, and research and development (R&D).

Initial inputs include seeds produced by plant nurseries and farmers. The agrochemical industry supports tobacco farming through sales of fertilizer, herbicides and pesticides20,28.

Primary processing requires specialist machine and knife makers to work with the tobacco industry29-32, including makers of green leaf threshing machinery30, machines to add flavoring or the flavoring itself27, and specialist packing units for transit33,34.

Secondary processing requires machinery to make cigarettes29,30, oral tobacco35, hookah equipment35, cigars36,37, and packaging30. Again, this machinery requires specialist knives31,38,39 and chemicals40. In addition to tobacco and chemicals, cigarettes include paper and filters. Paper is provided by farmers growing flax, hemp, rice, sisal, and linen41. Tree growing and felling produces the pulp for both paper41 and filters42. Packaging companies provide the cartons, boxes, paper, ink, cellophane, foil, glue, and tins for the industry40,43-50.

Logistics includes storing and transporting tobacco and tobacco products51, but also making the equipment for printing serialized codes and other markers to trace products from source to final destination52-55.

Marketing takes different forms depending on client and audience. Often overlooked is how these firms market their products and services within the industry, such as when tobacco and leaf firms use marketing to attract and retain farmers. In Brazil, for example, this is via industry associations and the Tobacco Growers Union20. Supporting industries such as paper and machinery advertise in tobacco industry magazines56 and specialist firms can be brought in to market these products and others57. Tobacco manufacturers, including the TTCs, market their products to retailers via retailer magazines58 – and directly to end-users, unless legislation is enacted and upheld59. Of course marketing is also a key component of TTCs campaigns to avoid such regulation60.

Finally, each stage of the supply chain and supporting industry requires R&D22. Cigarette filters, for example, have received particular R&D attention since standardized packs legislation is limiting innovation via packaging61,62.

DISCUSSION

Clearly TTCs require support from a large number of actors and industries to bring products to market and secure their profits. Such an expanded understanding of the tobacco supply chain can be used to better inform governmental, corporate, civil society and laypersons’ choices about careers, investments, and purchases. It could also be used to inform evaluations of company claims around, for example, contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals63 or their corporate social responsibility practices64 and the extent to which such contributions are on balance advantageous in situations where a company is also working with the tobacco industry.

This preliminary analysis illustrates that to identify potential leverage points in these supply chains and design effective policy to influence them, research and campaigns need to look beyond the TTCs. However, future supply chains study will also need to consider carefully the best way to identify and use industry source materials to establish differences between these and other sources, and how information contained might be best used without compromising the integrity of the research.

While this supply chain mapping exercise is just a start, future research can build from this to, for example, understand the relative value capture for different actors at different stages of production, which can act as a proxy for who controls supply chain governance. Likewise, mapping supply chains onto political jurisdictions could identify further policy pressure points and gaps in research and regulation. For example, to date, much of the existing research on intermediate actors within the supply chain has taken place in Asia and future work in Africa and South America could help provide a richer picture. Note that future work in this area might consider an even more expansive notion of the tobacco supply chain. For example, while they did not come up in our review results, one could potentially include additional service providers as supporting industries, including those supplying legal services or those involved in government relations (i.e. lobbyists).

Supply chain mapping offers a strong grounding for further work aimed at countering tobacco industry arguments about the benefits of production. For example, while in some ways advantageous to all parties6, TTCs design supply chains to maximize their own profits at the expense of farmers65 and careful mapping can elucidate this asymmetrical distribution of profits. Additionally, supply chain mapping can expose otherwise hidden costs of tobacco production, for example its contribution to climate change23, deforestation40, and destruction of aquatic life66 or the ways in which the supply chain reduces global capacity for food and manufacturing of products that would promote human health and wellbeing67.

CONCLUSIONS

Bringing supply chain mapping to the attention of tobacco control can potentially aid the development of effective public health policy by identifying under-researched processes, actors and supporting industries, shedding light on the tobacco industry’s reach, and revealing new opportunities for regulation.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none was reported.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products project funding (www.bloomberg.org).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed to the design of the literature review, editing the manuscript and approved the final version. RH carried out the literature review, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and created the visualization. MB wrote the introductory text on supply chains and the discussion.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42811/9241591013.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(Suppl 1):117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Action on Smoking and Health Tobacconomics. https://ash.org.uk/information-and-resources/tobacco-industry-information-and-resources/tobacconomics/. Published June 10, 2011. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 4.Garde A, Zrilič J. International Investment Law and Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention: An Introduction. The Journal of World Investment & Trade. 2020;21(5):649–673. doi: 10.1163/22119000-12340190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhāle S, Bhāle S. Setting a value chain through integrated supply chain in Indian agribusiness – the Indian Tobacco Company way. In: McIntyre JR, Ivanaj S, Ivanaj V, editors. CSR and Climate Change Implications for Multinational Enterprises. Gloucester, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jovanović MN. The Supply Chain Economy: How Far does it Spread in Space and Time? International Economics. 2019;72(4):393–452. http://www.iei1946.it/upload/rivista_articoli/allegati/292_jovanovic-ricfinalx.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gereffi G. The Organization of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How U.S. Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks. In: Gereffi G, Korzeniewicz M, editors. Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 1994. pp. 95–122. https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/11457/1994_Gereffi_Role%20of%20big%20buyers%20in%20GCCs_chapter%205%20in%20CC%26GC.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gereffi G, Humphrey J, Sturgeon T. The governance of global value chains. Rev Int Polit Econ. 2005;12(1):78–104. doi: 10.1080/09692290500049805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson J, Dicken P, Hess M, Coe N, Wai-Chung Yeung H. Global Production Networks and the Analysis of Economic Development. Rev Int Polit Econ. 2002;9(3):436–464. doi: 10.1080/09692290210150842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomfield M. Global Production Networks and Activism: Can Activists Change Mining Practices by Targeting Brands? New Political Economy. 2017;22(6):727–742. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2017.1321624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein B, Newell JP. How to track corporations across space and time. Ecol Econ. 2020;169:106492. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goger A, Bamber P, Gereffi G. The Tobacco Global Value Chain in Low-Income Countries. Durham, NC: Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness, Duke University; 2014. https://gvcc.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014-02-05_Duke-CGGC_WHO-UNCTAD-Tobacco-GVC-Report.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobacco Board India Indian Tobaccos [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(September):3. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_sep19_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis C,, Novotny TE, Lee K, Freiberg M, McLaughlin I. Tobacco industry responsibility for butts: a Model Tobacco Waste Act. Tob Control. 2017;26(1):113–117. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andri KB, Santosa P, Arifin Z. An Empirical Study of Supply Chain and Intensification Program on Madura Tobacco Industry in East Java. International Journal of Agricultural Research. 2011;6(1):58–66. doi: 10.3923/ijar.2011.58.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makoka D, Drope J, Appau A, et al. Costs, revenues and profits: an economic analysis of smallholder tobacco farmer livelihoods in Malawi. Tob Control. 2017;26(6):634–640. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulik MC, Bialous SA, Munthali S, Max W. Tobacco growing and the sustainable development goals, Malawi. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(5):362–367. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.175596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briones RM. Small Farmers in High-Value Chains: Binding or Relaxing Constraints to Inclusive Growth? World Dev. 2015;72:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drope J, Makoka D, Lencucha R, Appau A. Farm-level economics of tobacco production in Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Centre for Agricultural Research and Development; 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Agrarian Development, World Health Organization Tobacco Growing, Family Farmers and Diversification Strategies in Brazil: Current Prospects and Future Potential for Alternative Crops. https://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/cop/events/2007/brazil_study.pdf. Published May 2007. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 21.Gereffi G. The Tobacco Value Chain. http://www.ncglobaleconomy.com/tobacco/value.shtml. Published 2014 . Accessed 2019.

- 22.Muchfirodin M, Guritno AD, Yuliando H. Supply Chain Risk Management on Tobacco Commodity in Temanggung, Central Java (Case study at Farmers and Middlemen Level) Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia. 2015;3:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.aaspro.2015.01.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zafeiridou M, Hopkinson NS, Voulvoulis N. Cigarette Smoking: An Assessment of Tobacco's Global Environmental Footprint Across Its Entire Supply Chain. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52(15):8087–8094. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang ZH, Ji SW, Yu ZZ, Tian Y, Gao YH. Tobacco Industry Collaborating Supply Chain Research and Strategy. In: Liu H, Yang Y, Shen S, Zhong Z, Zheng L, Feng P, editors. Applied Mechanics and Materials. 268-270. 2012. pp. 2035–2039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiqi K, Scammell K, Huque R, et al. Smokeless Tobacco Supply Chain in South Asia: A Comparative Analysis Using the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(4):424–430. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider JE, Peterson NA, Kiss N, Ebeid O, Doyle AS. Tobacco litter costs and public policy: a framework and methodology for considering the use of fees to offset abatement costs. Tob Control. 2011;20(Suppl 1):i36–i41. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith EA, McDaniel PA. Covering their butts: responses to the cigarette litter problem. Tob Control. 2011;20(2):100–106. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.036491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araújo MCB, Costa MF. From Plant to Waste: The Long and Diverse Impact Chain Caused by Tobacco Smoking. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2690. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hauni Körber Solutions website https://www.hauni.com/en/home/. Accessed 2019.

- 30.About us. TSAL 360o world of tobacco. https://www.tsalengineering.com/about/. Accessed 2019.

- 31.Arkote World leaders in tobacco knife manufacturing [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(April/May):18. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_aprmay19_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arkote Tobacco Cutting Knives [Advertisement] www.arkote.com/home/products/tobacco_cutting_knives/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 33.Gladman C. A Low Oxygen Solution [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(June):30. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_jun19_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffin Cardwell Limited website http://www.griffincardwell.com/home.html. Accessed 2018.

- 35.Gramener Size of companies. https://gramener.com/companysize/?search=#soex. Published 2013. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 36.Isatec Fenix [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(July/August):16. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_julaug19_tpi-q2. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isatec Online Cigar Weight Measurement & Control. http://isatecfenix.co.uk/. Accessed 2019.

- 38.Arkote Cigarette Cutting Knives. http://www.arkote.com/home/products/cigarette_cutting_knives/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 39.Arkote The worldwide group of Fi-Tech Inc companies. http://www.arkote.com/home/why_arkote/fi-tech_group/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 40.Novotny TE, Bialous SA, Burt L, et al. The environmental and health impacts of tobacco agriculture, cigarette manufacture and consumption. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(12):877–880. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.152744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Global Tobacco Paper Market 2019 2027 Absolute Market Insights. https://www.absolutemarketsinsights.com/reports/Global-Tobacco-Paper-Market-2019-2027-350. Published January 2020. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 42.Cerdia International GmbH Products & Innovation. https://www.cerdia.com/en/products-and-innovation.html. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 43.BMJ Twist your imagination show the world differently [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(July/August):4–5. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_julaug19_tpi-q2. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Our Values BMJ. https://www.bmjpaperpack.com/index.php/site/ourValueHVP/high-values-products. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 45.Bobst at a glance BOBST. https://www.bobst.com/uken/about-bobst/who-we-are/bobst-at-a-glance/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 46.IST Metz GmbH website https://www.ist-uv.com/en/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 47.Contact Conzzeta. https://conzzeta.com/en/contact/. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 48.Locations. Hoffmann Neopac AG https://www.hoffmann-neopac.com/en/company. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 49.Products. Hoffmann Neopac AG https://www.hoffmann.ch/en/tins. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 50.Contact. Hoffmann Neopac AG. https://www.hoffmann-neopac.com/en/contact. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 51.Tabaknatie website https://www.tabaknatie.be. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 52.KÖHL Maschinenbau AG . Tobacco Automation. KÖHL solutions with power; https://www.koehl-mb.eu/en/products/tobacco-technology/tobacco-automation/. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Köhl Heinen. The Data agent: 100% traceability for packs and bundles [Advertisement] Tobacco International. 2019;(October/November):42. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_octnov19_tpi-q2_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Track & Trace Pack Program Enlists Coding Station Approach. Tobacco International. 2019;(June):28–29. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_jun19_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Domino Printing website https://www.domino-printing.com/en-gb/home.aspx. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 56.Addresses and Brands. Tobacco Journal International. 2018;(6):121–153. [Google Scholar]

- 57.United States: Will an All-Virginia Cigarette Find Favor in the United States? Tobacco International. 2019;(June):13. https://issuu.com/tobaccointernational/docs/ti_jun19_flipbook. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans-Reeves K, Hiscock R, Lauber K, Branston J, Gilmore AB. Prospective longitudinal study of tobacco company adaptation to standardised packaging in the UK: identifying circumventions and closing loopholes. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028506. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boseley S, Collyns D, Lamb K, Dhillon A. How children around the world are exposed to cigarette advertising. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/mar/09/how-children-around-the-world-are-exposed-to-cigarette-advertising. Published March 9, 2018. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 60.Wallbank LA, MacKenzie R, Beggs PJ. Environmental impacts of tobacco product waste: International and Australian policy responses. Ambio. 2017;46(3):361–370. doi: 10.1007/s13280-016-0851-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schweitzer-Mauduit International Engineered tobacco papers. https://www.swmintl.com/markets/tobacco/engineered-tobacco-papers. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 62.Evans-Reeves KA, Lauber K, Hiscock R. The ‘filter fraud’ persists: the tobacco industry is still using filters to suggest lower health risks while destroying the environment. Tob Control. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056245. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.United Nations Development Programme Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html#:~:text=The%20Sustainable%20Development%20Goals%20(SDGs. Accessed December 11, 2020.

- 64.Rangan VK, Chase L, Karim S. The Truth About CSR. Harvard Business Review. 2015;93(1/2):40–49. https://hbr.org/2015/01/the-truth-about-csr. Published 2015. Accessed December 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sexton RJ, Xia T. Increasing Concentration in the Agricultural Supply Chain: Implications for Market Power and Sector Performance. Annu Rev Resour Economics. 2018;10:229–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slaughter E, Gersberg RM, Watanabe K, Rudolph J, Stransky C, Novotny TE. Toxicity of cigarette butts, and their chemical components, to marine and freshwater fish. Tob Control. 2011;20(Suppl 1):i25–i29. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.040170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lencucha R, Thow AM. How Neoliberalism Is Shaping the Supply of Unhealthy Commodities and What This Means for NCD Prevention. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(9):514–520. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]