Abstract

This study reported two cases of intracranial thrombotic events of aplastic anemia (AA) under therapy with cyclosporine-A (CsA) and reviewed both drug-induced cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) and CsA-related thrombotic events systematically. We searched PubMed Central (PMC) and EMBASE up to Sep 2019 for publications on drug-induced CVT and Cs-A-induced thrombotic events. Medical subject headings and Emtree headings were used with the following keywords: “cyclosporine-A” and “cerebral venous thrombosis OR cerebral vein thrombosis” and “stroke OR Brain Ischemia OR Brain Infarction OR cerebral infarction OR intracerebral hemorrhage OR intracranial hemorrhage.” We found that CsA might be a significant risk factor in inducing not only CVT but also cerebral arterial thrombosis in patients with AA.

Keywords: cyclosporine-A, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, cerebral arterial infarction, case report, systematic review

Background

Cyclosporine-A (CsA) is widely used as an immunosuppressive agent in organ transplantation (1–3), ulcerative colitis (UC) (4–6), and aplastic anemia (AA) (7). Most commonly, the high incidences of thromboembolic complications in the renal vascular system were found in patients with CsA use after kidney transplantation (8, 9), which might be due to acute and chronic nephrotoxicity of CsA. However, thrombotic complications in other organs secondary to CsA use are not fully analyzed in the clinical settings (10). In particular, cases of CsA-induced intracranial thrombotic complications in patients with AA were rather rare (7). Herein, we presented two cases of AA with CsA-related intracranial thrombotic events, involved in cerebral venous sinuses and cerebral arteries, respectively. Besides, we conducted a systematic literature review of CsA-related thrombotic events to give more clinical references to physicians in this field.

Moreover, it is well-known that oral contraceptive (OCP) use is regarded as the iatrogenic risk factor inducing cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). However, there is by far no review on if any other medications that could also cause CVT. Therefore, inspired by our case of CsA-induced CVT, we further comprehensively reviewed drug-induced CVT.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 15-year-old female with a 4-year history of AA with treatment of CsA (50 mg, bid) complained of an intermittently severe headache on her left frontoparietal areas for 8 months. Her headache could initially attenuate after intravenous injection of mannitol (125 ml, q8h) for 7 days. However, her headache was recurrent and even became aggressively severe with nausea and projectile vomiting 20 days ago, which could no longer be relieved by the former treatment of mannitol. Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 36.4°C, blood pressure of 105/85 mmHg, heart rate of 78/min, and respiratory rate of 20/min. No abnormal finding was found in the neurological examination. Fundoscopy showed stage V papilledema measured by the Frisén scale (Supplementary Figure 1).

Her complete blood cell (CBC) test indicated moderate normocytic normochromic anemia and a decreased platelet level due to her primary disease. The serum iron test was normal, which further excluded the differential diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia. Baseline levels of inflammatory biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP) (37.2 mg/L, normal 1.0–8.0 mg/L), high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) (25.75 mg/L, normal 0.0–3.0 mg/L), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) (19.6 pg/ml, normal 0.0010–7.0 pg/ml) were all above the upper normal limits (Supplementary Table 1), which suggested acute inflammatory reaction secondary to the primary disease. An increased level of D-dimer (2.47 μg/ml, normal range 0.01–0.5 μg/ml) and fibrinogen (4.21 g/L, normal range 2.0–4.0 g/L) remained over the upper limit of the normal range for several days after admission, suggesting the formation of thrombosis at acute stage (Supplementary Table 1). Serum neuron-specific enolase (NSE) level at admission was 51.52 ng/ml (normal range 0.0–17.0 ng/ml). The elevated NSE was related to damage to both neurons and the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Investigation for vasculitis [antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and antiphospholipid antibody (APLA)] was negative. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profile revealed a slightly increased white blood cell (WBC) count (2 × 106/L), and lumbar puncture opening pressure (LPOP) was over 330 mm H2O. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance venography (CE-MRV) (Figure 1) and high-resolution MRI with black-blood thrombus image (MRBTI) of the brain (Figure 2) demonstrated subacute thrombosis in the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), straight sinus, right transverse sinus (TS), right sigmoid sinus (SS), and proximal part of right internal jugular vein (IJV). Moreover, no parenchymal lesion was found in MRBTI. The confirmed diagnosis of subacute CVT in multiple sites was made based on imaging findings, with involvement in cerebral venous sinuses and IJV. The CVT-induced cerebrospinal venous insufficiency could cause disturbance of CSF circulation, further leading to intracranial hypertension and related symptoms, such as severe headaches and projectile vomiting. However, the etiology of CVT development was hard to be explained in this case due to lacking common risk factors like other female CVT patients, such as obesity, pregnancy, or long-term OCP use. Moreover, no positive result was found in the workup of thrombophilia, including protein S (PS), protein C (PC), antithrombin-III (AT-III), Factor VII/VIII deficiency, or Factor V Leiden mutation. Then, we closely monitored her blood cell counts on an everyday basis. Her hypercoagulable state induced by moderate anemia secondary to AA and probable adverse effect of CsA on damaging venous vessel walls raised our attention. The procoagulant effect of the two factors might potentiate the formation of CVT.

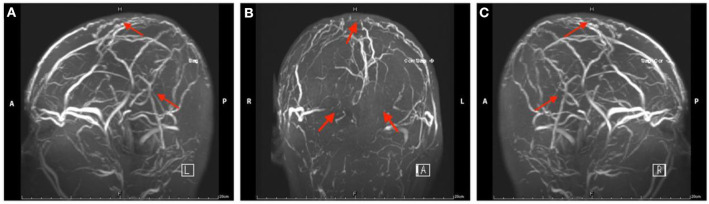

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance venography images of head in Case 1. The red arrow indicates the focal stenosis of cerebral venous sinus and venous collateral circulation.

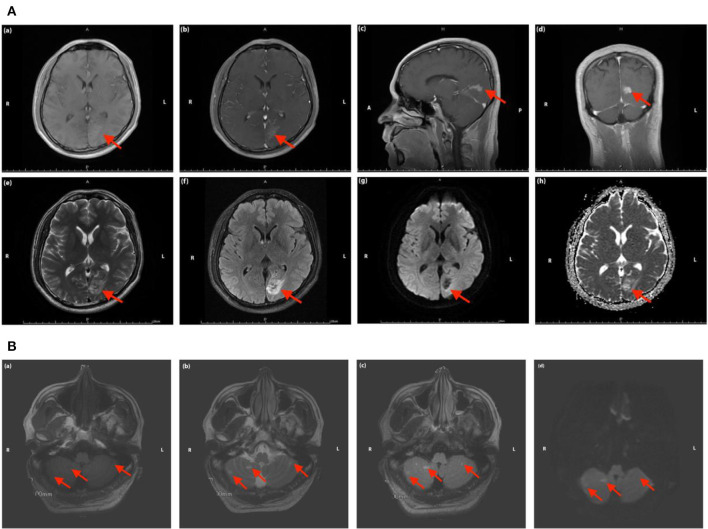

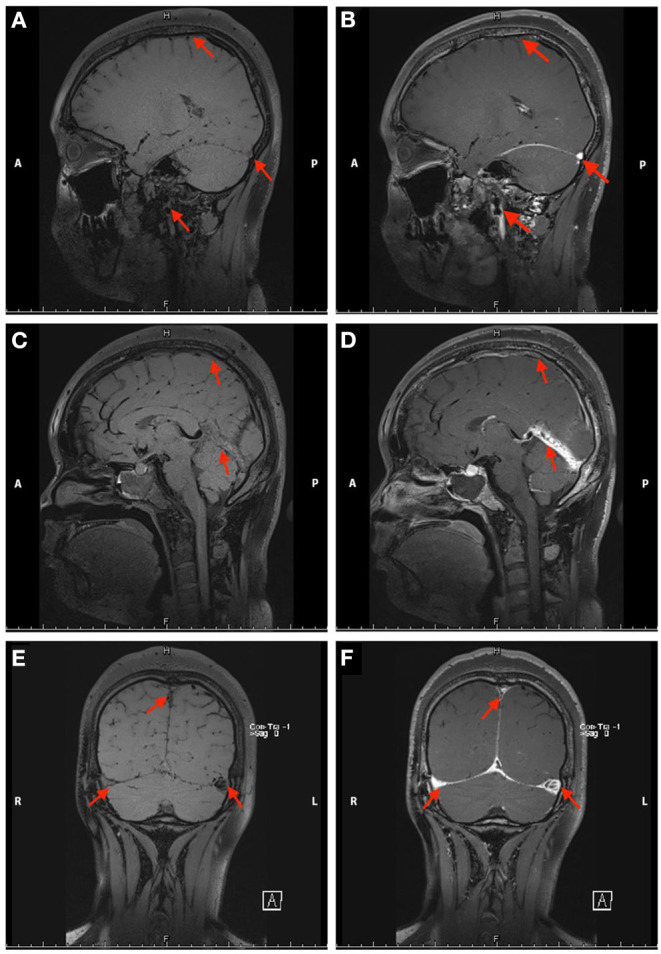

Figure 2.

Non-contrast enhanced (A,C,E) and contrast-enhanced (B,D,F) black-blood thrombus images of the head in Case 1. The red arrow indicates the focal stenosis of the internal jugular vein and cerebral vein sinus.

Intravenous injection of mannitol (125 mL, q8h) was continued after the admission. Subcutaneous injection enoxaparin sodium (0.6 ml, qd) was started when the diagnosis of CVT was confirmed and usage of CsA was suspended after consultation with the department of hematology. The usage of enoxaparin sodium was then bridged to rivaroxaban (20 mg, qd) when she was discharged. Outpatient follow-up after 6 months of standard anticoagulation was evaluated by the Patients' Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale. The patient reported a definite improvement of her symptoms (PGIC score = 6) and was transferred to the department of hematology to further treat AA.

Case 2

A 34-year-old male with a 1-year treatment of CsA (50 mg, bid) for AA presented with right homonymous hemianopia for 20 days, accompanied by dizziness and right-hand numbness. There was no history of nausea and vomiting, motor or sensory symptoms in the limbs, facial bulbar symptoms, sphincter incontinence, and loss of consciousness or seizures. He denied a family history of blood clotting disorders. Physical examination showed his body temperature was 36.9°C, blood pressure was 130/84 mmHg, heart rate was 72 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 beats/min. Neurological examination revealed no positive findings.

Peripheral blood test demonstrated mild normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin, 110 g/L, normal range 120–160 g/L; hematocrit 34.8%, normal range 38.0–50.8%). The evaluation of thrombophilia showed increased levels of fibrinogen (4.11 g/L, normal range 2.0–4.0 g/L), D-dimer (1.4 μg/ml, normal range 2.0–4.0 g/L), AT-III (134%, normal range 80.0–120.0%), and protein C (181%, normal range 65.0–140.0%). All the results of serological tests, including aPL, ANA, ANCA, and complements C3 and C4, were negative. Workups of proinflammatory biomarkers, such as CRP, hs-CRP, and IL-6, were all negative. LPOP was 200 mmH2O, and a slightly elevated level of protein (57 mg/dl, normal range 15.0–45.0 mg/dl) and WBC count in CSF was found (5 × 106/L). Serum NSE was more than two times higher than the normal upper limit (36.59 ng/ml, normal range 0.0–17.0 ng/ml). MRI indicated cerebral infarction in the left occipital lobe (Figure 3A) and both sides of the cerebellum (Figure 3B). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed focal stenosis in the distal branches of the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and a partial filling defect in both sides of the superior cerebellar arteries (Figure 4). CE-MRV excluded the possibility of CVT (Figure 5). As this patient has not been identified to have any vascular risk factors, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity or smoking history, family history of small vessel disease, or state of hypercoagulability, and the evidence of systemic autoimmune diseases was also negative, we assumed that the cerebral atrial infarction was caused by emboli from cardiac source or thrombosis in situ secondary to certain unknown injuries. Then, to further evaluate the potential cause of stroke, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was conducted, with negative findings of atrial septal abnormalities [patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal defect (ASD), or atrial septal aneurysm (ASA)]. Based on the patient's medical history of using CsA, the direct or indirect adverse effect of CsA may contribute to the damage in arterial vessel walls, which further initiated the formation of thrombosis in situ. The usage of CsA was withdrawn after consultation with the department of hematology due to his relatively well-controlled condition of AA. Aspirin (100 mg, qd) was prescribed at discharge.

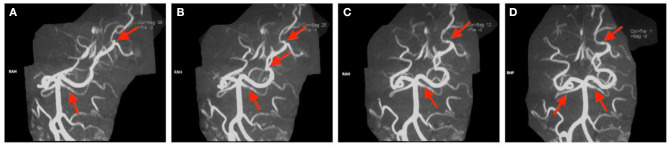

Figure 3.

(A) Magnetic resonance images of the head in Case 2. The red arrow indicates the focal ischemic infarction in left occipital lobe [(a) T1 sequence; (b–d) T1 sequence with contrast-enhancing; (e) T2 sequence; (f) T2 FLAIR sequence; (g) DWI sequence; (h) ADC sequence]. (B) Magnetic resonance images of the head in Case 2. The red arrow indicates the focal ischemic infarction in cerebellum [(a) T1 sequence; (b) T2 sequence; (c) T2 FLAIR sequence; (d) DWI sequence].

Figure 4.

(A–D) Magnetic resonance arthrography images of the head in Case 2. The red arrow indicates partial filling defects.

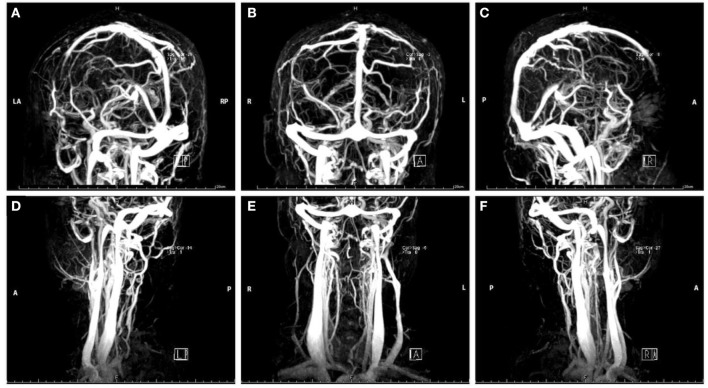

Figure 5.

Magnetic resonance venography images of the head (A–C) and neck (D–F) in Case 2.

MRI follow-up at 6 months post-stroke showed no new-onset parenchymal lesions, and his symptoms were partially relieved and evaluated by PGIC scale (PGIC score = 6).

Literature Review

We searched PubMed Central (PMC) and EMBASE up to Sep 2019 for publications on CsA-induced thrombotic events and drug-induced CVT. We used Medical subject headings and Emtree headings combining with the following keywords: “cyclosporine-A” and “cerebral venous thrombosis OR cerebral vein thrombosis” and “stroke OR Brain Ischemia OR Brain Infarction OR cerebral infarction OR intracerebral hemorrhage OR intracranial hemorrhage.” We also screened reference lists of included articles for additional relevant studies. Intracranial thrombotic events had to be diagnosed by MRI, conventional angiography, computed tomography (CT) angiography, or at surgery or autopsy. Articles written in languages other than English were only selected if they had an English abstract with sufficient data.

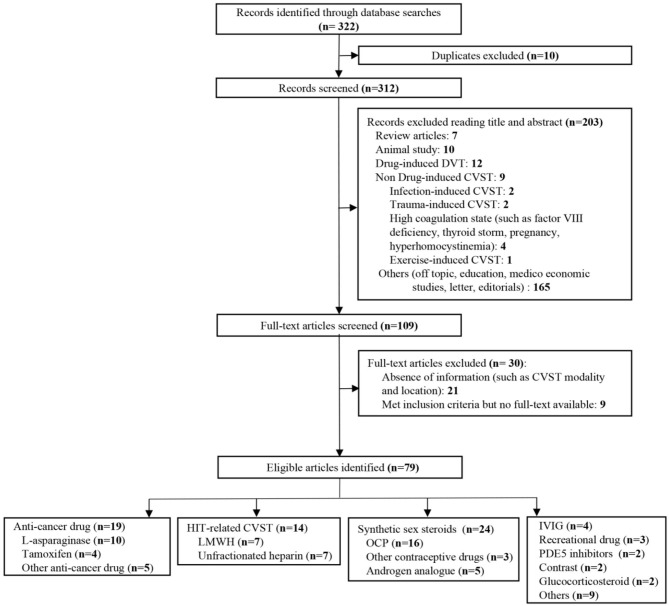

We identified 322 publications related to drug-induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), of which 109 were selected for full-length review (Figure 6). Among these, 79 articles with a total of 706 patients were included based on our inclusion criteria. However, nine articles within the inclusion criteria were not collected due to no access to full texts despite that we searched for several times and tried to contact corresponding authors by e-mail. Herein, we listed these nine references in Supplementary Materials. Most of the eligible studies were case reports or case series (n = 68) and retrospective studies (n = 9), and only one meta-analysis and one prospective study were found (Table 1) (11–89). Western countries reported 95% of the cases, followed by eastern countries (4%), while only one case was from African countries. The mean age of patients was 33.8 ± 17.9 years, and 68.5% of patients were female. There were 94 pediatric cases (94/706, 13.3%). The most common symptoms were seizures (48.6%), headaches (38.1%), nausea/vomiting (19.5%), altered mental status (drowsiness, confusion, syncope, or coma) (17.6%), motor/sensory disorder (12.9%), visual disturbance (9.0%), and aphasia/dysphasia (7.6%). The least common symptoms were personality/behavior change (aggressiveness, n = 1; irritability, n = 4; poor personal care, n = 1) (2.9%) and ataxia (2.4%). Only few cases reported symptoms like general malaise/fatigability (n = 2), fever (n = 2), diarrhea (n = 2), and urinary incontinence (n = 1). CVT was confirmed by CE-MRV (n = 55) and MRI (n = 18). Although digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was considered the gold standard, only 13 cases conducted DSA to make the defined diagnosis. Besides, CT (n = 5), CT venography (CTV) (n = 5) and autopsy (n = 5) were also mentioned as method to detect CVT. Among all sinuses, SSS (n = 123) was most likely involved in drug-induced CVT, followed by the TS (n = 119), SS (n = 97), and straight sinus (n = 80). Thrombosis was usually formed bilaterally in the TS (n = 26), while it was less common in the left TS (LTS) (n = 23) and the right TS (RTS) (n = 14). However, the left SS (LSS) more potentially formed thrombosis (n = 18) than the right SS (RSS) (n = 9); 60.3% of cases had multiple sinus thromboses (105/174). CVST combined with cortical vein thrombosis (CoVT) and isolated CoVT were reported in 102 cases and 6 cases, respectively. Drug-induced deep cerebral vein thrombosis was only found in a vein of Galen, combined with CVST (n = 2). Furthermore, CVST was also found to coexist with jugular system thrombosis (n = 70), while isolated jugular system thrombosis was very rare (n = 2). Nineteen articles indicated contraceptive drug-induced CVT, and 14 studies reported heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) that resulted in CVT. l-Asparaginase was widely used in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), while 10 publications demonstrated the close relationship between CVT and l-asparaginase. Furthermore, CsA use was also a risk factor for CVT (n = 7).

Figure 6.

Flow diagram of the study selection process on drug-induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST).

Table 1.

Drug induced cerebral venous thrombosis.

| Drug | Age/gender | Primary disease | Symptoms | CVST | References | Country | Article type | Study size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modality | Location | ||||||||

| Contrast | |||||||||

| Iopamidol | 36/F | Myelography | NR | DSA | SSS | (11) | France | Case report | 1 |

| 24/M | Recurrent left sciatica (Myelography) | Headache (severe), nausea and vomiting | DSA | SSS, RLS | (12) | France | Case report | 1 | |

| Recreational drug | |||||||||

| MDMA type synthetic drugs | |||||||||

| Ecstasy | 22/F | None | Headache, nausea, visual disturbance (photophobia, visual fortification spectra), expressive dysphasia, and right hemisensory loss. | DSA | TS | (13) | UK | Case report | 1 |

| Speed | 19/F | None | Uncontrollable aggressiveness | MRV | LTS | (14) | Spain | Case report | 1 |

| Cocaine | 30/M | None | Headache (Occipital) and vomiting | MRV | SSS, TS | (15) | UK | Case report | 1 |

| Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors | |||||||||

| Tadalafil | 45/M | None | Headache (severe, posterior, sudden-onset, 3-day), and seizure (generalized tonic-clonic) | MRI | RCoVT | (16) | Japan | Case report | 1 |

| Sildenafil | 57/M | Two episodes of venous thrombosis (DVT; hemorrhoid plexus thrombosis) | Headache (occipital, 2-week) and visual disturbance (blurry vision) | MRV | SSS, RSS, RTS | (17) | Italy | Case report | 1 |

| IVIG | 16/F | ITP | Headache (severe), neck rigidity, and vomiting | MRI | SSS | (18) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| 11/M | ITP | Headache (severe, transient frontotemporal) | CTV | SSS | (19) | Canada | Case report | 1 | |

| 11/M | Humoral immunodeficiency (Bruton's disease) | Expressive aphasia, right upper extremity heaviness | CTV | SSS | (20) | Lebanon | Case report | 1 | |

| 13/F | ITP | Headache | MRI | LIJV | (21) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| Others | |||||||||

| Dulaglutide | 52/F | DM-2 | Headache (3-day) and visual disturbance (blurry vision) | MRV | RTS | (22) | India | Case report | 1 |

| Romiplostim | 45/F | ITP | Headache (severe, occipital) | MRV | SSS, TS | (23) | Taiwan | Case report | 1 |

| Epoetin alfa | 37/F | End stage renal disease | Headache (progressive, several-day) | MRV | SSS, SS | (24) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Dietary supplements | 63/M | well-controlled hypertension | Seizure (generalized tonic-clonic) | DSA | SS, vein of Galen | (25) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Lithum | 30/F | Bipolar disorder | Headache (progressive), confusion, visual disturbance (blurry vision), and left hemiparesis. | DSA | SSS, LSS, LTS, straight sinus | (26) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Finasteride | 35/M (case 1) 41/M (case 2) |

Male-pattern hair loss | Headache and seizures (case 1); Headache (case 2) |

CTV | SSS | (27) | Japan | Case report | 2 |

| Combination tacrolimus/sirolimus | 67/M | Renal transplantation | Seizure (generalized) and right hemiparesis | MRI | TS | (28) | Australia | Case report | 1 |

| Clozapine | 30/F | Chronic paranoid schizophrenia | Vomiting, irritability, fatigability, poor personal care (5-day) | MRV | SSS, ISS, RTS, RIJV | (29) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Levetiracetam | 6.5/M | None | Headache and vomiting (2-day), then seizures (generalized) | MRI | LTS, LSS | (30) | UK | Case report | 1 |

| Synthetic sex steroids | |||||||||

| Oral contraception | |||||||||

| Phytoestrogens | 52/F | None | Headache (diffuse and continuous, 2-month) | MRV | LLS, LSS | (31) | Portugal | Case report | 1 |

| Third-generation CHCs (containing desogestrel or gestoden) | 16–49/F | CVTh | Seizure (n = 52) | CTV/MRV | CVT: dural sinuses, DCVT, CoVT, IJV | (32) | USA | Retro | 57 |

| Ethinylestradiol/ levonorgestrel |

21/F | None | Headache (severe, 4-day) | CTV | SSS, CoVT, RTS, RSS | (33) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| NR | 18/F (case 1) 23/F (case 2) |

Protein C resistance (case 1); Anti-thrombin III deficiency (case 2) |

Headache, nausea, vomiting and visual disturbance (photophobia) (case 1); Headache, vomiting, altered sensorium (case 2) |

MRI | SSS, TS, LSS (case 1) SSS (case 2) |

(34) | India | Case report | 2 |

| NR | 18/F (case 1) 18/F (case 2) |

None (case 1); ADHD and bipolar disorder (case 2) |

Headache (intermittent right-sided) and visual disturbance (blurry vision) (3-day) (case 1); Headache (intermittent right-sided) and visual disturbance (double vision) (6-week) (case 2) |

MRV | LTS, LSS (case 1); RTS, IJV (case 2) |

(35) | USA | Case report | 2 |

| NR | 27/F (case 1) 23/F (case 2) |

None | Headache (retroauricular), vomiting, drowsiness, fever (several days) (case 1); Headache, vomiting, increasing drowsiness and extra-pyramidal movements (1 day) (case 2). |

DSA (case 1) MRI (case 2) |

LTS, SS (case 1); SSS, SS (case 2) |

(36) | Italy | Case report | 2 |

| Ethinylestradiol/ desogestrel |

24/F | None | Headache (severe, 1 week), vomiting. | DSA | SSS, RLS, RSS, vein of Galen | (37) | Czech Republic | Case report | 1 |

| Noracyclina (case 1) Ovulenb (case 2) |

50/F (case 1) 41/F (case 2) |

None (case 1); Thrombosis of left common carotid (case 2) |

Fluctuated conscious status, aphasia, right arm weakness, and several epileptic seizures (case 1); Right hand numbness and rapid-onset unconsciousness (case 2) |

Necropsy | SSS, CoVT (case 1, 2); | (38) | Switzerland | Case report | 2 |

| Lyndiol 2, 5 (case 1) Metrulen-M (case 2) Anovlar (case 3) Gynovlar (case 4) Nuvacon (case 5) |

24/F (case 1) 49/F (case 2) 30/F (case 3) 23/F (case 4) 29/F (case 5) |

RIJVS (case 1) Diabetes (case 2) Right pulmonary embolus (case 3) Thrombosis of choroid plexus (case 4) Marfan's syndrome; thrombosis of iliac vein (case 5) |

Headache, vomiting and drowsiness (5-day) (case 1); Headache, vomiting, seizure (generalized, left-sided) (case 2); Deeply comatose (case 3); Diarrhea, headache (severe) and further unconsciousness (case 4); Abdominal pain, headache (severe, 1-day), and vomiting (5-day) (case 5). |

Necropsy | SSS, RTS, SS, CoVT, IJV (case 1); SSS, RTS, LTS, CoVT (case 2, 3, 5); All sinuses thrombosis, CoVT (case 4) |

(39) | NR | Case report | 5 |

| Norethynodrel and mestranol | 35/F | Eclampsia during pregnancy; obesity | Headache (severe, persistent, temporal) (4-day), vomiting, diarrhea, seizure, urinary incontinence, upper limb weakness (left-sided), and visual disturbance (photophobia) | Necropsy | SSS, LTS, CoVT | (40) | NR | Case report | 1 |

| Enovid (case 1) Ortho novum (case 2) |

29/F (case 1, 2) | Multiple arterial thrombi; thrombosis of left opththalmic vein; Marfan's syndrome (case 2) |

NR | Necropsy | All sinuses thrombosis, CoVT (case 1); SSS (case 2) |

(41) | NR | Case report | 2 |

| Combined oral contraceptives (COCs), progestin-only contraceptives or cyproterone acetate. | 15–49/F | Former thromboembolic event (including PE, CVT, ischemic stroke, or MI) | NR | NR | CVT | (42) | France | Retro | 452 |

| Yasmin 28c | 18/F | None | Headache (Throbbing, frontal and occipital, 1-month) | MRV | RTS, RSS, IJV, CoVT | (43) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| NR | 22/F | None | Severe headache (1 week) | CT/MRV/DSA | LTS, LSS | (44) | China | Case report | 1 |

| Cyproterone/gestodene | 50/F | Heterozygous factor II polymorphism | NR | NR | CVST | (45) | Italy | Retro | 1/28 |

| NR | 23–45/F | Prothrombin mutation G20210A (n = 2) | Headache (n = 11), vomiting (n = 2), aphasia (n = 1) | MRA (n = 10) DSA (n = 7) |

Straight sinus (n = 15) TS (n = 7) |

(46) | Spain | Retro | 15 |

| Other contraceptive drugs | |||||||||

| Norethisterone enanthate injection | 23/F | None | Headaches (progressive), vomiting (repeated) and syncope (2–3 min) | MRV | SSS, RTS, RSS | (47) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Vaginal contraceptive ringd | 28/F | None | Headache | CT | LSS, TS | (48) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| 33/F | None | Seizures (multiple tonic-clonic), headaches | CT | LTS, LSS, LIJV | (49) | Canada | Case report | 1 | |

| Androgen analog | |||||||||

| Oxymetholone | 40/F | AA | NR | MRI | SSS, LTS | (50) | South Korea | Case report | 1 |

| Nandrolone decaonoate | 22/M | None | Headaches and vomiting (repeated) (3-day) | MRV | SSS, TS | (51) | Iran | Case report | 1 |

| Fluoxymesterone | 52/F (case 1) 39/F (case 2) |

Hypoplastic anemia | Headaches (severe), seizures, aphasia and hemiplegia, coma (case 1) Headaches (severe) and seizure (focal) (case 2) |

DSA | SSS (case 1) SSS, CoVT (case 2) |

(52) | USA | Case report | 3 |

| Methenolone-enanthate | 26/F (case 3) | Headaches, visual disturbance (blurred vision), and hemiparesis (right-sided) (case 3) | SSS, CoVT (case 3) | ||||||

| Danazole | 40/M | AA | Headache (acute onset) and altered sensorium | CT | CoVT | (53) | India | Case report | 1 |

| 19/M | IHA | Headache and visual disturbance (transient obscurations of vision) | DSA | SSS, CoVT, straight sinus | (54) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| Steroid | 32/F | Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis | Numbness and weakness (both legs) | MRV | LTS, LSS | (55) | Turkey | Case report | 1 |

| 31/M | IHA | Headaches, anorexia, general malaise | DSA | SSS, CoVT, straight sinus | (52) | Japan | Case report | 1 | |

| HIT-related CVST | |||||||||

| LMWH | 60/F | Bilateral extensive varicose veins in legs | Right focal seizures with secondary generalization followed by headache, slurred speech, and altered sensorium | MRI/CTV | LTS, LSS | (56) | India | Case report | 1 |

| 52/F | Kyphoplasty and posterior spinal fusion | Acute onset altered mental status with significant agitation and non-sensical speech. | MRV | LTS, LSS, LIJV | (57) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| 55/F | Partial gastrectomy | NR | MRV | SSS, SS, LIJV | (58) | Germany | Case report | 1 | |

| 57/F | Antiphospholipid syndrome and possible systemic lupus erythematosus | Fever, altered mental status, and aphasia (expressive and sensory) | MRV | SSS, LSS, LIJV | (59) | Greece | Case report | 1 | |

| 69/F | Knee replacement for osteoarthritis | Seizures (right arm focal type) | MRV | SSS, CoVT | (60) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| 72/M | Left knee joint surgery | Comatose | Necropsy | SSS, SS, CoVT | (61) | Germany | Case report | 1 | |

| 38 ± 28 | NR | NR | MRV | CVT | (62) | Germany | Retro | 3/120 | |

| Unfractionated heparin | 61/F | Retinal transient ischemic attack; DVT of the leg | Headache (progressive) and aphasia | MRI | LLS | (63) | France | Case report | 1 |

| 18/M | Extensive UC | Headache (severe), nausea and vomiting | MRI | RTS, confluence area | (64) | Sweden | Case report | 1 | |

| 45/F | Cystic pituitary adenoma. | Aphasia and visual disturbances | MRI | LTS, LSS | (65) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| 67/F | NR | NR | CTV | SSS | (66) | Germany | Case report | 1 | |

| 63/F | Polycythemia vera | Seizures (right-sided focal type) | Contrast-enhanced CT | SSS | (67) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| 36/F | PNH | Headache, nausea, then developed dysphasia and right hemiparesis | MRV | LTS, LSS | (68) | Japan | Case report | 1 | |

| 67/F | Antiphospholipid syndrome | Headache (transient), vertigo, tinnitus and right hemifacial par-aesthesia with propagation down to the ipsilateral arm. | MRV | RTS, RSS, IJV | (69) | Switzerland | Case report | 1 | |

| Anti-cancer drugs | |||||||||

| Tamoxifen | 40/F | Breast cancer | Headache and hemiparesis (left-sided) (10-day) | MRI | SSS, RLS, RIJV | (70) | Turkey | Case report | 1 |

| 30/F | Breast cancer | Headache (acute-onset) and hemiparesis (left-sided) | DSA/MRI | SSS | (71) | South Korea | Case report | 1 | |

| 46/F | Breast cancer | Headache (severe) and nausea (subacute onset, 2-week) | MRI/CT | SSS, straight sinus | (72) | South Korea | Case report | 1 | |

| 47/F | Breast cancer | Headache (Severe), seizure (generalized tonic-clonic) | MRV | SSS, CoVT | (73) | USA | Case report | 1 | |

| L-asparaginase | 15/M | ALL | Acute severe headache and recurrent vomiting | MRV | SSS, TS, straight sinus | (74) | Germany | Case report | 1 |

| 10/M (case 1) 13/F (case 2) |

ALL (case 1) Acute mixed phenotypic leukemia (case 2) |

Headache, vomiting, seizures and loss of consciousness (case 1) Headache and focal seizure (case 2) |

MRV | SSS (case 1 & 2) | (75) | India | Case report | 2 | |

| 5–16 | ALL (n = 8) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 1) |

Headaches (chronic, daily), and seizures (partial-complex)g | MRV | LTS, LSS, LIJV (case 1) CVST (case 2) SSS (case 3) TS (case 4) |

(76) | USA | Retro | 9/200 | |

| 2.3/M (case 1) 3.5/F (case 2) |

ALL (case 1 & 2) | Seizure (left focal seizure evolving into generalized tonic-colonic seizure and subsequently status epilepticus) (case 1); Seizure (left focal seizure evolving into status epilepticus) (case 2) |

MRV (case 1 & 2) | SSS (case 1 & 2) | (77) | India | Case report | 2 | |

| (1–17)/(38/10, M/F) | ALL | Headache (n = 14), a decreased level or loss of consciousness (n = 15), visual impairment (n = 3), focal or generalized seizures (n = 18), photophobia (n = 1), vomiting (n = 8), irritability (n = 3), hemiparesis (n = 5), ataxia (n = 2), speech impairment (n = 6), and cranial nerve palsy (n = 1). | CT (n = 38), MRV (n = 27) | CoVT (n = 3), CVST (n = 26), CVST combined with CoVT (n = 4) |

(78) | Italy | Retro | 33/48 | |

| 5.6 (1.0–17.0)/(38/33, M/F) | ALL | NR | MRI | CVT | (79) | Austria | Pro | 3/71 | |

| 9/M | ALL | Headache (Acute-onset, severe) and then seizures (left-sided focal type) and right arm sensory disturbance. | MRI | SSS | (80) | Saudi Arabia | Case report | 1 | |

| 32 (15–59)/(144/96, M/F) | ALL or lymphoblastic lymphoma | NR | NR | CVT | (81) | France | Retro | 5/214 | |

| NA | ALL | NR | NR | CVT | (82) | Italy | Meta-analysis | 26/1,752 | |

| 16/M | ALL | Headache, vomiting, and multiple episodes of seizures | Contrast enhanced CT | CoVT | (83) | India | Case report | 1 | |

| L-asparaginase or Tamoxifenf | 44.5 (10-71)/(16/4, M/F) | Hematologic malignancies (n = 9); Solid tumor (n = 11) | Headache (n = 8), seizure (n = 6), nausea/vomiting (n = 5), hemiparesis/aphasia (n = 4), altered metal status/coma (n = 3), dizziness (n = 3), visual disturbance (n = 2), gait disturbance (n = 1), incidental finding (n = 1), not available (n = 1) | MRV | SSS (n = 13), TS (n = 8), SS (n = 5), IJV (n = 4), straight sinus (n = 1) | (84) | USA | Retro | 20 |

| Cisplatin and BEP | 16/F | Immature teratoma | Hemiparesis (left-sided) | MRI | SSS | (85) | Tunisia | Case report | 1 |

| Thalidomide | 74/F | Multiple myeloma | Headache (right-sided, frontal), confusion and speech difficulty (acute-onset) | MRI | LTS, straight sinus, CoVT, LIJV | (86) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| Methotrexate | 12/M | ALL | Hemiparesis (right-sided), aphasia, altered mental status, persistent seizure activity, and progressive neurological deterioration | MRI | LTS, LSS | (87) | USA | Case report | 1 |

| ATRA | 22/F | APML | Visual disturbance (blurred vision on the right eye) | MRV | SSS, RSS, TS, IJV | (88) | Malaysia | Case report | 1 |

R, right; L, left; SS, sigmoid sinus; SSS, superior sagittal sinus; TS, transverse sinus; LS, lateral sinus; CVT, cerebral venous thrombosis; CVST, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis; CoVT, cortical vein thrombosis; IJVS, internal jugular vein stenosis; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APML, acute promyelocytic leaukaemia; HIT, Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; AA, Aplastic anemia; DM, diabetes mellites; PNH, Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; UC, ulcerative colitis; MI, myocardial infarction; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; IHA, immune hemolytic anemia; ITP, immune thrombocytopenia; PE, pulmonary emboli; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CTV, CT venography; MRV, magnetic resonance venography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; CHCs, combined hormonal contraceptives; ATRA, All-trans retinoic acid; BEP, bleomycin and etoposide; IVIG, Intravenous immunoglobulins; Retro, retrospective; Pro, prospective; NR, not reported.

Noracyclin = Lynestrenol/mestranol.

Ovulen = Ethinodiol diacetate/mestranol.

Yasmin 28 = drospirenone.

Vaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing): etonogestrel and ethinyl-estradiol per day.

Danazol is an attenuated androgen derived from ethisterone (17 α-ethinyltestosterone).

This study enrolled patients with hematologic malignancies or solid tumors.

All patients survived, with 4 experiencing complications possibly related to CVST. In this article, report these four patients in detail.

Female patients with diagnosed cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) of the dural sinuses, involvement of the deep venous system (DCVT), cortical venous thrombosis, or with thrombosis of the jugular system.

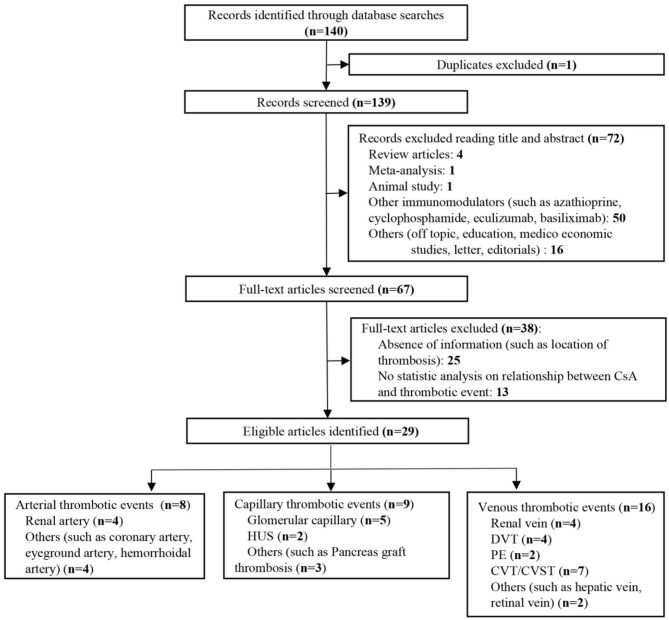

We further searched articles related to CsA-induced thrombotic events to explore if CsA would bring extensive damage to different kinds of blood vessels. One hundred forty articles were identified, and full texts of 67 articles were screened (Figure 7). Only studies with sufficient information and a clear description of the relationship between CsA and thrombosis were finally included (n = 29). CsA was more likely associated with venous thrombotic events (n = 16), followed by capillary thrombotic events (n = 9) and arterial thrombotic events (n = 8). CVT was the most common thrombosis in CsA-induced thrombotic events (Table 2) (1–9, 90–109). Thrombosis in the renal vessel system was more likely formed due to CsA use in renal transplantation (n = 13).

Figure 7.

Flow diagram of the study selection process on cyclosporine-A (CsA)-induced thrombosis.

Table 2.

Cyclosporine-A induced thrombosis.

| Age/gender | Thrombosis location | Primary disease | References | Country | Study size | Article type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | DVT (n = 25), PE (n = 4), DVT with PE (n = 11) |

Renal transplantation | (90) | UK | 40/480 | Retro |

| 41 ± 12 | DVT | Renal transplantation | (91) | Switzerland | 9/97 | Pro |

| 52/M (case 1) 26/M (case 2) 32/M (case 3) 61/M (case 4) 11/M (case 5) 54/M (case 6) 45/F (case 7) |

Glomerular capillary; Renal afferent artery |

Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (92) | UK | 7 | Case report |

| NA | Cyclosporine-associated arteriopathy (acute tubular necrosis; acute vasculitis; glomerular ischemia; interstitial intimate; Intima proliferation; venous thrombosis) | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (93) | USA | 16/200 | Retro |

| 36.7 ± 1.3/(49/41, M/F) | PE (n = 10), Renal vein (n = 1), DVT (n = 3), Hemorrhoidal artery (n = 3) |

Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (8) | Belgium | 13/90 | Retro |

| 35.9 ± 13.8 | DVT | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor, living-donor) | (94) | Sweden | 9/97 | Pro |

| 53/F (case 1) 33/M (case 2) 48/F (case 3) |

HUS, Glomerular capillaries, Renal artery |

Renal transplantation | (95) | Canada | 3 | Case report |

| 33/F | Glomerular capillaries | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (96) | UK | 1 | Case report |

| NA | Glomerular capillaries (Platelet microthrombi) | Renal transplantation | (97) | UK | 12/32 | Retro |

| NA | Renal artery | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor, living-donor) | (98) | China | 1/14 | Retro |

| 6 (case 1) 6 (case 2) 17 (case 3) 48 (case 4) 53 (case 5) 51 (case 6) |

Renal vein | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor, living-donor) | (99) | UK | 6/791 | Retro |

| NA | HUS, Glomerular capillaries | Behcet's disease | (100) | France | 2 | Case report |

| NA | CVST | SSINS | (101) | UK | 1/53 | Retro |

| 45.1 ± 12.3 | Renal vein | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (102) | UK | 16 | Pro |

| NA | Eyeground artery | Recurrent nephrotic syndrome | (103) | Japan | 1 | Case report |

| NA | CVT | Renal transplantation | (104) | Spain | 1 | Case report |

| 25.0 ± 26.4 | HUS | Renal transplantation | (105) | USA | 10/672 | Retro |

| NA | Hepatic vein | Inflammatory bowel disease and latent thrombocythemia | (106) | France | 1 | Case report |

| 19/M | CVST | Severe active UC | (5) | Japan | 1 | Case report |

| 48/F | CVST (LTS, LSS), LIJVS | Chronic UC | (4) | USA | 1 | Case report |

| NA | Thrombotic microangiopathy | SPK transplantation | (107) | Belgium | 1/102 | Retro |

| (18–55) | Pancreas graft thrombosis (n = 10), Kidney graft thrombosis (n = 1) |

SPK transplantation | (9) | Belgium | 11/102 | Pro |

| 31 ± 11 | Graft thrombosis (combined arterial and venous thrombotic occlusion, n = 5; arterial occlusion, n = 3, venous occlusion, n = 1) | SPK transplantation | (3) | Austria | 9/67 | Retro |

| 30/F | Central retinal vein | Renal transplantation (cadaver-donor) | (108) | Croatia | 1 | Case report |

| 56.7 ± 10.1 | Coronary artery | Heart transplantation | (2) | Canada | 18/129 | Retro |

| 25/M | CVST (SSS, TS) | Renal transplantation (living-donor) | (1) | Sri Lanka | 1 | Case report |

| 23/F | CVT | Neuro-Behcet's disease | (109) | Brazil | 3/40 | Retro |

| 18–64/(28/33, F/M) | Venous thrombosis | Acute steroid-refractory or dependent UC | (6) | Finland | 1/61 | Pro |

| 44/F | CVST | AA | (7) | China | 1 | Case report |

R, right; L, left; CVT, cerebral vein thrombosis; CVST, cerebral vein sinus thrombosis; CoVT, cortical vein thrombosis; SSS, superior sagittal sinus; TS, transverse sinus; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, Pulmonary emboli; SPK transplantation, Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation; HUS, Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome; AA, Aplastic anemia; SSINS, steroid sensitive idiopathic nephrotic syndrome; UC, ulcerative colitis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; Retro, retrospective; Pro, prospective; NR, not reported.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables with a normal distribution were specified as mean ± standard deviation. Analyses were performed with Stata software (version 15.0 SE, Stata Corp, LP, Texas, USA).

Discussion

This was the first systematic review on drug-induced CVT and CsA-related thrombosis based on the clinical cases. CVT is a rare subtype of stroke, accounting for <1% of all strokes (110). Severe CVT can be fatal. Common etiologies of CVT are postpartum period, infection, and coagulopathies (111). However, drug-induced CVT should not be neglected, as this kind of CVT could be reversible and preventable if we avoid certain drugs when treating primary diseases, for instance, the two cases presented in this study. In line with CVT of other etiologies, the most common symptoms in drug-induced CVT were seizures (48.6%) and headaches (38.1%). Furthermore, women or young people were mainly involved. Both CE-MRV and black-blood thrombus image (BBTI) are useful imaging tools to make a definitive diagnosis.

It would be worth noticing that CsA can induce not only CVT but also cerebral arterial thrombosis, as in Case 2 of this report. Interestingly, drug-induced CVT is more likely involved in multiple sinuses, cortical veins, or IJV, such as Case 1 in this paper. It is well-known that OCP can promote CVT in women, whereas CsA-related CVT should also raise our concern.

Cyclosporine thrombogenicity manifested mostly with CVT. However, the underlying mechanism is still controversial. Several adverse effects of CsA had been reported in patients: Firstly, CsA enhanced secretion of von Willebrand factor (VWF), a classic platelet agonist, from endothelial cells (112). Then, platelet aggregation was increased due to a higher level of VWF in circulation (113). Thirdly, CsA-induced endothelial cell dysfunction by suppressing nitric oxide production and initiating intrinsic coagulation pathway (10, 114). Further, CsA was associated with increased D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, which were observed in our patients after the onset of the thrombotic event, which was consistent with other studies (4, 8, 115). However, some animal and clinical studies showed that CsA therapy was not related to thrombosis in renal transplant and even provided strong protection from both reperfusion injury (97) and congestive heart failure (116) or improved recovery after treatment of coronary thrombosis with angioplasty (117).

Moreover, apart from the thrombogenic effect of CsA, patients with AA frequently presented with decreased levels of WBC, RBC, or platelet. Anemia secondary to AA could also be associated with both CVT (118) and arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) (119). More importantly, anemia was correlated with stroke severity and poor clinical outcomes in AIS patients (120, 121). Thus, a well-controlled condition of AA is vital to prevent cerebral thrombotic events. Besides, a stronger association between anemia and CVT in men than in women (118), which reminded us that the potential confounders, such as age and gender, should also be taken into consideration when treating AA patients with thrombotic complications.

Although we cannot prove the clear relationship between the potential adverse effect of CsA, anemia secondary to AA, and intracranial thrombotic events in these two cases due to the rarity of similar cases, CsA-induced intracranial thrombosis in AA patients was firstly reported. This observation may at least warrant caution of monitoring thrombotic events during CsA treatment in patients with AA. Therefore, we suggested that future studies could shed more light on the mechanism of the prothrombotic effects of Cs-A in the treatment of AA patients. Additionally, the systematic literature review on CsA-related thrombotic events and drug-induced CVT would give more clinical references to physicians in this field, especially when treating patients with unknown reasons for stroke.

Summary Table

What Is Known About This Topic?

A possible association may exist between cyclosporine-A use and thrombotic events in patients with aplastic anemia.

Currently, there is a lack of information on comprehensive review on drug-induced cerebral venous thrombosis and cyclosporine-A-related thrombotic events.

What Does This Paper Add?

This real-world study provides two cases with aplastic anemia that developed intracerebral thrombotic events due to cyclosporine-A use.

Articles on cyclosporine-A-related thrombotic events were reviewed. CsA-induced thrombosis may involve the arteries, veins, and capillaries. Damage to the renal vascular system was most commonly reported due to the acute and chronic nephrotoxicity of CsA.

Studies on drug-induced cerebral venous thrombosis were selected, of which we summarized features of clinical characteristics and neuroimaging findings.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Xuanwu Hospital, Beijing, China. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

RM drafted and revised the manuscript and provided the study concept and design. S-YS drafted and revised the manuscript, provided the study concept and design, and carried out collection, assembly, and interpretation of the data. RM, S-YS, Y-CD, Z-AW, and X-MJ wrote the manuscript and gave final approval of the manuscript. Y-CD intensively edited the revised version and contributed to the critical revision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two patients for allowing us to publish their medical experience for scientific use.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was sponsored by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1308400), the National Natural Science Foundation (81371289), and the Project of Beijing Municipal Top Talent for Healthy Work of China (2014-2-015).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2020.563037/full#supplementary-material

Funduscopic imaging of Case 1.

Follow up of abnormal examination in Case 1.

References

- 1.Rajapakse S, Gnanajothy R, Lokunarangoda N, Lanerolle R. A kidney transplant patient on cyclosporine therapy presenting with dural venous sinus thrombosis: a case report. Cases J. (2009) 2:9139. 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White M, Ross H, Haddad H, LeBlanc MH, Racine N, Pflugfelder P, et al. Subclinical inflammation and prothrombotic state in heart transplant recipients: impact of cyclosporin microemulsion vs. tacrolimus. Transplantation. (2006) 82:763–70. 10.1097/01.tp.0000232286.22319.e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steurer W, Malaise J, Mark W, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R. Spectrum of surgical complications after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation in a prospectively randomized study of two immunosuppressive protocols. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2005) 20:ii54–61. 10.1093/ndt/gfh1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Shekhlee A, Oghlakian G, Katirji B. A case of cyclosporine-induced dural sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. (2005) 3:1327–8. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murata S, Ishikawa N, Oshikawa S, Yamaga J, Ootsuka M, Date H, et al. Cerebral sinus thrombosis associated with severe active ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. (2004) 43:400–3. 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieminen U, Turunen U, Arkkila P, Sipponen T, Af Björkesten CG, Färkkilä MA. Cyclosporin A in acute steroid-refractory or dependent ulcerative colitis: a prospective study on long term outcome. U Eur Gastroenterol J. (2014) 2:A535 10.1177/2050640614548980 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao F, Zhang J, Wang F, Xin X, Sha D. Cyclosporin A-related cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a case report. Medicine. (2018) 97:e11642. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanrenterghem Y, Lerut T, Roels L. Thromboembolic complications and haemostatic changes in cyclosporin-treated cadaveric kidney allograft recipients. Lancet. (1985) 1:999–1002. 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91610-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saudek F, Malaise J, Bouček P, Adamec M. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus compared with cyclosporin microemulsion in primary spk transplantation: 3-year results of the euro-spk 001 trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2005) 20:ii3–10. 10.1093/ndt/gfh1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez E, Rosado JA, Redondo PC. Immunophilins and thrombotic disorders. Curr Med Chem. (2011) 18:5414–23. 10.2174/092986711798194405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glowinski J, Breuillard P, Delafolie A, Redondo A. thrombosis of the superior longitudinal sinus after sacculoradiculography with iopamidol. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. (1986) 53:183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brugeilles H, Pénisson-Besnier I, Pasco A, Oillic P, Lejeune P, Mercier P. Cerebral venous thrombosis after myelography with iopamidol. Neuroradiology. (1996) 38:534–6. 10.1007/BF00626091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell PM, Grant R. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis induced by 'ecstasy'. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1993) 56:1035 10.1136/jnnp.56.9.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Méndez-Sánchez F, Guisado JA, Palacios R, Teva I. Intracranial sinus thrombosis secondary to the consumption of inhaled speed. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. (2011) 39:404–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns H, Rich P, Al-Memar AY. An unpleasant hit from cocaine: a case of cocaine-induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2012) 83:A1 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304200a.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Numata K, Shimoda K, Shibata Y, Shioya A, Tokuda Y. The development of cerebral venous thrombosis after tadalafil ingestion in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Intern Med. (2017) 56:1235–7. 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.7864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rufa A, Cerase A, Monti L, Dotti MT, Giorgio A, Sicurelli F, et al. Recurrent venous thrombosis including cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a patient taking sildenafil for erectile dysfunction. J Neurol Sci. (2007) 260:293–5. 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benadiba J, Robitaille N, Lambert G, Itaj NK, Pastore Y. Intravenous immunoglobulin-associated thrombosis: is it such a rare event? Report of a pediatric case and of the quebec hemovigilance system. Transfusion. (2015) 55:571–5. 10.1111/trf.12897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Riyami AZ, Lee J, Connolly M, Shereck E. Cerebral sinus thrombosis following iv immunoglobulin therapy of immune thrombocytopenia purpura. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2011) 57:157–9. 10.1002/pbc.22968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barada W, Muwakkit S, Hourani R, Bitar M, Mikati M. Cerebral sinus thrombosis in a patient with humoral immunodeficiency on intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: a case report. Neuropediatrics. (2008) 39:131–3. 10.1055/s-2008-1077088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iroh Tam PY, Richardson M, Grewal S. Fatal case of bilateral internal jugular vein thrombosis following ivig infusion in an adolescent girl treated for itp. Am J Hematol. (2008) 83:323–5. 10.1002/ajh.21107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajput R, Pathak V, Yadav PK, Mishra S. Dulaglutide-induced cerebral venous thrombosis in a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Case Rep. (2018) 2018:bcr2018226346. 10.1136/bcr-2018-226346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho P, Khan S, Crompton D, Hayes L. Extensive cerebral venous sinus thrombosis after romiplostim treatment for immune thrombocytopenia (itp) despite severe thrombocytopenia. Intern Med J. (2015) 45:682–3. 10.1111/imj.12765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finelli PF, Carlcy MD. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with epoetin alfa therapy. Arch Neurol. (2000) 57:260–2. 10.1001/archneur.57.2.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newey CR, Sarwal A, Tepper D. Iatrogenic venous thrombosis secondary to supplemental medicine toxicity. J complement integrat Med. (2013) 10:129–34. 10.1515/jcim-2012-0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasay M, Bakshi R, Kojan S, Bobustuc G, Dubey N. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis due to lithium: local urokinase thrombolysis treatment. Neurology. (2000) 54:532–3. 10.1212/WNL.54.2.532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuji Y, Nakayama T, Bono K, Kitamura M, Imafuku I. Two cases of stroke associated with the use of finasteride, an approved drug for male-pattern hair loss in japan. Clin Neurol. (2014) 54:423–8. 10.5692/clinicalneurol.54.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graves A, Kulkarni H. Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis temporally associated with combination tacrolimus/sirolimus immunosuppression. Nephrology. (2013) 18:75–6. 10.1111/nep.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srinivasaraju R, Reddy YC, Pal PK, Math SB. Clozapine-associated cerebral venous thrombosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2010) 30:335–6. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181deb88a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohamed BP, Prabhakar P. Thrombocytopenia as an adverse effect of levetiracetam therapy in a child. Neuropediatrics. (2009) 40:243–4. 10.1055/s-0030-1247524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guimaraes J, Azevedo E. Phytoestrogens as a risk factor for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2005) 20:137–8. 10.1159/000086805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roethlisberger M, Gut L, Zumofen DW, Fisch U, Boss O, Maldaner N, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis requiring invasive treatment for elevated intracranial pressure in women with combined hormonal contraceptive intake: risk factors, anatomical distribution, and clinical presentation. Neurosurg focus. (2018) 45:E12. 10.3171/2018.4.FOCUS1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wharton HC. A 21-year-old white woman diagnosed with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis related to oral contraceptive and factor v leiden. Adv Emerg Nurs J. (2012) 34:10–5. 10.1097/TME.0b013e318243552c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wankhade V, Patil S, Joshi G, Kadhe N, Pawar S, Maulik N. Oc pills induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a case series. Indian J Pharmacol. (2013) 45:S162. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan JJ, Hassoun A, Elmalem VI. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with ophthalmic manifestations in 18-year-olds on oral contraceptives. Clin Pediatr. (2014) 53:826–30. 10.1177/0009922814533405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosi R, Stanca A, Monfregola MR, Malandrini A, Fabrizi GM, Galluzzi P, et al. Aggressive treatment of severe acute cerebral venous thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives in young women. Clin Intensive Care. (1995) 6:36–9. 10.3109/tcic.6.1.36.39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prochazka V, Rajner J, Prochazka M, Dvorak J, Cizek V. Oral contraceptive induced cerebral venous thrombosis treated by local catheter directed thrombolysis. Interv Neuroradiol. (2004) 10:321–8. 10.1177/159101990401000406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poltera AA. The pathology of intracranial venous thrombosis in oral contraception. J pathol. (1972) 106:209–19. 10.1002/path.1711060402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atkinson EA, Fairburn B, Heathfield KW. Intracranial venous thrombosis as complication of oral contraception. Lancet. (1970) 1:914–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(70)91046-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buchanan DS, Brazinsky JH. Dural sinus and cerebral venous thrombosis. incidence in young women receiving oral contraceptives. Arch neurol. (1970) 22:440–4. 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480230058006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh FB, Clark DB, Thompson RS, Nicholson DH. Oral contraceptives and neuro-ophthalmologic interest. Arch Ophthalmol. (1965) 74:628–40. 10.1001/archopht.1965.00970040630009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petitpain N, Gourbil M, Grandvuillemin A, Beyens MN, Massy N, Gras V, et al. Hormonal contraception or cyproterone acetate and thromboembolic events: a study in 30 french public hospitals. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. (2014) 28:104–5. 10.1111/fcp.12066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez MA, Glaser JS, Schatz NJ. “Idiopathic” intracranial hypertension caused by venous sinus thrombosis associated with contraceptive usage. Optometry. (2010) 81:351–8. 10.1016/j.optm.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang Q, Chai X, Xiao C, Cao X. A case report of oral contraceptive misuse induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and dural arteriovenous fistula. Medicine. (2019) 98:e16440. 10.1097/MD.0000000000016440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Girolami A, Spiezia L, Girolami B, Zocca N, Luzzatto G. Effect of age on oral contraceptive-induced venous thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb/Hemost. (2004) 10:259–63. 10.1177/107602960401000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galarza M, Gazzeri R. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives: the case for neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus. (2009) 27:E5. 10.3171/2009.8.FOCUS09158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahall M, Santlal M. Norethisterone enanthate-induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (cvst). BMJ Case Rep. (2017) 2017:bcr2017222418. 10.1136/bcr-2017-222418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolacki C, Rocco V. The combined vaginal contraceptive ring, nuvaring, and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. (2012) 42:413–6. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunne C, Malyuk D, Firoz T. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a woman using the etonogestrel-ethinyl estradiol vaginal contraceptive ring: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. (2010) 32:270–3. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34454-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu K, Kang DW, Kim DE, Roh JK. Cerebral venous thrombosis associated with tentorial subdural hematoma during oxymetholone therapy. J Neurol Sci. (2001) 185:27–30. 10.1016/S0022-510X(01)00448-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahraian MA, Mottamedi M, Azimi AR, Moghimi B. Androgen-induced cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a young body builder: case report. BMC Neurol. (2004) 4:22. 10.1186/1471-2377-4-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shiozawa Z, Ueda R, Mano T, Tsugane R, Kageyama N. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis associated with evans' syndrome of haemolytic anaemia. J Neurol. (1985) 232:280–2. 10.1007/BF00313866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sudheer Kumar G, Roopesh Kumar VR, Gopalakrishnan MS, Shankar Ganesh CV, Venkatesh MS. Danazol-induced life-threatening cerebral venous thrombosis in a patient with aplastic anemia. Neurol India. (2011) 59:762–4. 10.4103/0028-3886.86557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamed LM, Glaser JS, Schatz NJ, Perez TH. Pseudotumor cerebri induced by danazol. Am J Ophthalmol. (1989) 107:105–10. 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90206-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gazioglu S, Solmaz D, Boz C. Cerebral venous thrombosis after high dose steroid in multiple sclerosis: a case report. Hippokratia. (2013) 17:88–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shah SD, Shah C, Vora R. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cerebral venous thrombosis after low-molecular weight heparin. Neurol India. (2010) 58:669–70. 10.4103/0028-3886.68688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gleichgerrcht E, Lim MY, Turan TN. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis due to low-molecular-weight heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Neurologist. (2017) 22:241–4. 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beland B, Busse H, Loick HM, Ostermann H, Van Aken H. Phlegmasia cerulea dolens, cerebral venous thrombosis, and fatal pulmonary embolism due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenic thrombosis syndrome. Anesth Analg. (1997) 85:1272–4. 10.1097/00000539-199712000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stavropoulos I, Liverezas A, Papageorgiou E, Tsiara S. A rare case of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with antiphospholipid syndrome and possible systemic lupus erythematosus. Aktualnosci Neurologiczne. (2017) 17:121–5. 10.15557/AN.2017.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fesler MJ, Creer MH, Richart JM, Edgell R, Havlioglu N, Norfleet G, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: case report and literature review. Neurocritic Care. (2011) 15:161–5. 10.1007/s12028-009-9320-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer P, Couzi G, Bavle J, Blanc P, Gibelin P, Camous JP, et al. Disseminated coronary thrombosis and pentosane polysulfate-induced thrombocytopenia. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. (1988) 81:913–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pohl C, Harbrecht U, Greinacher A, Theuerkauf I, Biniek R, Hanfland P, et al. Neurologic complications in immune-mediated heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Neurology. (2000) 54:1240–5. 10.1212/WNL.54.6.1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richard S, Perrin J, Lavandier K, Lacour JC, Ducrocq X. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to essential thrombocythemia and worsened by heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. Platelets. (2011) 22:157–9. 10.3109/09537104.2010.527399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thorsteinsson GS, Magnusson M, Hallberg LM, Wahlgren NG, Lindgren F, Malmborg P, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in an 18-year old male with severe ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2008) 14:4576–9. 10.3748/wjg.14.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Refaai MA, Warkentin TE, Axelson M, Matevosyan K, Sarode R. Delayed-onset heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, venous thromboembolism, and cerebral venous thrombosis: a consequence of heparin “flushes”. Thromb Haemost. (2007) 98:1139–40. 10.1160/TH07-06-0423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merz S, Fehr R, Gülke C. Sinus vein thrombosis. a rare complication of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia type ii. Anaesthesist. (2004) 53:551–4. 10.1007/s00101-004-0687-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kyritsis AP, Williams EC, Schutta HS. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Stroke. (1990) 21:1503–5. 10.1161/01.STR.21.10.1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ishihara-Kawase K, Ohtsuki T, Sugihara S, Tanaka H, Nakamura T, Kimura A, et al. Cerebral sinus thrombosis and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Intern Med. (2010) 49:941–3. 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsieh J, Kuzmanovic I, Vargas MI, Momjian-Mayor I. Cerebral venous thrombosis due to cryptogenic organising pneumopathy with antiphospholipid syndrome worsened by heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. BMJ Case Rep. (2013) 2013:bcr2013009500. 10.1136/bcr-2013-009500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akdal G, Donmez B, Cakmakci H, Yener GG. A case with cerebral thrombosis receiving tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Neurol. (2001) 8:723–4. 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hwang SK. A case of dural arteriovenous fistula of superior sagittal sinus after tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. (2015) 57:204–7. 10.3340/jkns.2015.57.3.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim J, Huh C, Kim D, Jung C, Lee K, Kim H. Isolated cortical venous thrombosis as a mimic for cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. (2016) 89:727.e5–7. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phuong L, Shimanovsky A. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis related to the use of tamoxifen: a case report and review of literature. Conn med. (2016) 80:487–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dietel V, Bührdel P, Hirsch W, Körholz D, Kiess W. Cerebral sinus occlusion in a boy presenting with asparaginase-induced hypertriglyceridemia. Klin Padiatr. (2007) 219:95–6. 10.1055/s-2007-921455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wani NA, Kosar T, Pala NA, Qureshi UA. Sagittal sinus thrombosis due to l-asparaginase. J Pediatr Neurosci. (2010) 5:32–5. 10.4103/1817-1745.66683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ross CS, Brown TM, Kotagal S, Rodriguez V. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in pediatric cancer patients: long-term neurological outcomes. J Pediatr Hematol/Oncol. (2013) 35:299–302. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31827e8dbd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Siddaiahgari SR, Makadia D, Lingappa L. Peg asparginase induced superior sagittal sinus thrombosis with status epilepticus pediatric in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (all): a report of 2 cases from India. J Pharmacol Toxicol. (2014) 9:129–33. 10.3923/jpt.2014.129.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Santoro N, Colombini A, Silvestri D, Grassi M, Giordano P, Parasole R, et al. Screening for coagulopathy and identification of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at a higher risk of symptomatic venous thrombosis: an aieop experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2013) 35:348–55. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31828dc614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meister B, Kropshofer G, Klein-Franke A, Strasak AM, Hager J, Streif W. Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin and antithrombin versus antithrombin alone for the prevention of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. (2008) 50:298–303. 10.1002/pbc.21222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alsaid Y, Gulab S, Bayoumi M, Baeesa S. Cerebral sinus venous thrombosis due to asparaginase therapy. Case Rep Hematol. (2013) 2013:841057. 10.1155/2013/841057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hunault-Berger M, Chevallier P, Delain M, Bulabois CE, Bologna S, Bernard M, et al. Changes in antithrombin and fibrinogen levels during induction chemotherapy with l-asparaginase in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. Use of supportive coagulation therapy and clinical outcome: the capelal study. Haematologica. (2008) 93:1488–94. 10.3324/haematol.12948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caruso V, Iacoviello L, Di Castelnuovo A, Storti S, Mariani G, de Gaetano G, et al. Thrombotic complications in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis of 17 prospective studies comprising 1752 pediatric patients. Blood. (2006) 108:2216–22. 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dubashi B, Jain A. L-asparginase induced cortical venous thrombosis in a patient with acute leukemia. J Pharmacol Pharmacotherapeut. (2012) 3:194–5. 10.4103/0976-500X.95531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Raizer JJ, DeAngelis LM. Cerebral sinus thrombosis diagnosed by mri and mr venography in cancer patients. Neurology. (2000) 54:1222–6. 10.1212/WNL.54.6.1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kridis WB, Khanfir A, Kammoun F, Mahfoudh KB, Triki C, Frikha M. A very rare cerebral complication of chemotherapy in a young girl: a difficult diagnosis. Curr Drug Saf . (2015) 10:257–60. 10.2174/1574886310666150518112823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lenz RA, Saver J. Venous sinus thrombosis in a patient taking thalidomide. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2004) 18:175–7. 10.1159/000079739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mahadeo KM, Dhall G, Panigrahy A, Lastra C, Ettinger LJ. Subacute methotrexate neurotoxicity and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in a 12-year old with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (mthfr) c677t polymorphism: homocysteine-mediated methotrexate neurotoxicity via direct endothelial injury. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2010) 27:46–52. 10.3109/08880010903341904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee KR, Subrayan V, Win MM, Fadhilah Mohamad N, Patel D. Atra-induced cerebral sinus thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. (2014) 38:87–9. 10.1007/s11239-013-0988-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shiozawa Z, Yamada H, Mabuchi C, Hotta T, Saito M, Sobue I, et al. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis associated with androgen therapy for hypoplastic anemia. Ann Neurol. (1982) 12:578–80. 10.1002/ana.410120613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen RD, Michie CA, Morris PJ, Chapman JR. Venous thrombosis and cyclosporin. Lancet. (1985) 2:1004 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90543-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bergentz SE, Bergqvist D, Bornmyr S. Venous thrombosis and cyclosporin. Lancet. (1985) 2:101–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90205-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neild GH, Reuben R, Hartley RB, Cameron JS. Glomerular thrombi in renal allografts associated with cyclosporin treatment. J Clin Pathol. (1985) 38:253–8. 10.1136/jcp.38.3.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sommer BG, Innes JT, Whitehurst RM, Sharma HM, Ferguson RM. Cyclosporine-associated renal arteriopathy resulting in loss of allograft function. Am J Surg. (1985) 149:756–64. 10.1016/S0002-9610(85)80181-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brunkwall J, Bergqvist D, Bergentz SE, Bornmyr S, Husberg B. Postoperative deep venous thrombosis after renal transplantation. Effects of cyclosporine. Transplantation. (1987) 43:647–9. 10.1097/00007890-198705000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Giroux L, Smeesters C, Corman J, Paquin F, Allaire G, St-Louis G, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in renal allografted patients treated with cyclosporin. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. (1987) 65:1125–31. 10.1139/y87-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muirhead N, Hollomby DJ, Keown PA. Acute glomerular thrombosis with csa treatment. Ren Fail. (1987) 10:135–9. 10.3109/08860228709047648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dunnill MS, Gatter KC, Mason DY, Morris PJ. Immunosuppression and thrombosis in renal transplantation: an immunohistological study. Histopathology. (1990) 16:79–82. 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb01065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fang GX, Chan PCK, Cheng IKP, Li MK, Wong KK, Chan MK. Haematological changes after renal transplantation: differences between cyclosporin-A and azathioprine therapy. Int Urol Nephrol. (1990) 22:181–7. 10.1007/BF02549838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Richardson AJ, Higgins RM, Jaskowski AJ, Murie JA, Dunnill MS, Ting A, et al. Spontaneous rupture of renal allografts: the importance of renal vein thromobosis in the cyclosporin era. Br J Surg. (1990) 77:558–60. 10.1002/bjs.1800770530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beaufils H, De Groc F, Gubler MC, Wechsler B, Le Hoang P, Baumelou A, et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients with behcet's disease treated with cyclosporin A: report of 2 cases. Clin Nephrol. (1990) 34:157–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Neuhaus TJ, Fay J, Dillon MJ, Trompeter RS, Barratt TM. Alternative treatment to corticosteroids in steroid sensitive idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. (1994) 71:522–6. 10.1136/adc.71.6.522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schleibner S, Krauss M, Wagner E, Erhard J, Christiaans M, Van Hooff J, et al. Fk 506 versus cyclosporin in the prevention of renal allograft rejection - european pilot study: six week results. Transplant Int. (1995) 8:86–90. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.1995.tb01481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ito S, Hosaka M, Beppu M, Nomura T, Uchida J. Case report of a recurrent nephrotic syndrome patient with sudden onset of blindness during treatment with cyclosporin A. Jpn J Nephrol. (1998) 40:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Guerrero AL, Arcaya J, Cacho J, Seisdedos L. Thrombosis of intracranial venous veins in a patient with kidney transplant and toxic serum levels of cyclosporin. Med Clin. (1999) 112:238–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Langer RM, Van Buren CT, Katz SM, Kahan BD. De novo hemolytic uremic syndrome after kidney transplantation in patients treated with cyclosporine-sirolimus combination. Transplantation. (2002) 73:756–60. 10.1097/00007890-200203150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Decaens T, Maitre S, Marfaing A, Naveau S, Chaput JC, Mathurin P. Inflammatory bowel disease and latent thrombocythemia: a novel cause of hepatic vein thrombosis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. (2004) 28:394–7. 10.1016/S0399-8320(04)94941-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kuypers DRJ, Malaise J, Claes K, Evenepoel P, Maes B, Coosemans W, et al. Secondary effects of immunosuppressive drugs after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2005) 20:ii33–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfh1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Simic P, Gasparovic V, Skegro M, Stern-Padovan R. Cholelithiasis and thrombosis of the central retinal vein in a renal transplant recipient treated with cyclosporin. Clin Drug Investig. (2006) 26:361–5. 10.2165/00044011-200626060-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dutra LA, Goncalves CR, Pedroso JL, Braga-Neto P, Gabbai AA, Barsottini OGP, et al. Neuro-behets disease in brazil: higher incidence in females and atypical manifestations. Arthritis Rheum. (2011) 63.20882667 [Google Scholar]

- 110.Einhaupl K, Stam J, Bousser MG, De Bruijn SF, Ferro JM, Martinelli I, et al. EFNS guideline on the treatment of cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in adult patients. Eur J Neurol. (2010) 17:1229–35. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Meng R, Ji X, Wang X, Ding Y. The etiologies of new cases of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis reported in the past year. Intractable Rare Dis Res. (2012) 1:23–6. 10.5582/irdr.2012.v1.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nolasco LH, Gushiken FC, Turner NA, Khatlani TS, Pradhan S, Dong JF, et al. Protein phosphatase 2b inhibition promotes the secretion of von willebrand factor from endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost. (2009) 7:1009–18. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03355.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fishman SJ, Wylonis LJ, Glickman JD, Cook JJ, Warsaw DS, Fisher CA, et al. Cyclosporin A augments human platelet sensitivity to aggregating agents by increasing fibrinogen receptor availability. J Surg Res. (1991) 51:93–8. 10.1016/0022-4804(91)90076-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dusting GJ. Nitric oxide in cardiovascular disorders. J Vasc Res. (1995) 32:143–61. 10.1159/000159089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ueda D, Suzuki K, Malyszko J, Pietraszek MH, Takada Y, Takada A, et al. Fibrinolysis and serotonin under cyclosporine a treatment in renal transplant recipients. Thromb Res. (1994) 76:97–102. 10.1016/0049-3848(94)90211-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Piot C, Croisille P, Staat P, Thibault H, Rioufol G, Mewton N, et al. Effect of cyclosporine on reperfusion injury in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:473–81. 10.1056/NEJMoa071142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Halestrap AP, Pasdois P. The role of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in heart disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. (2009) 1787:1402–15. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Coutinho JM, Zuurbier SM, Gaartman AE, Dikstaal AA, Stam J, Middeldorp S, et al. Association between anemia and cerebral venous thrombosis: case-control study. Stroke. (2015) 46:2735–40. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Chang YL, Hung SH, Ling W, Lin HC, Li HC, Chung SD. Association between ischemic stroke and iron-deficiency anemia: a population-based study. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e82952. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Khan MF, Shamael I, Zaman Q, Mahmood A, Siddiqui M. Association of anemia with stroke severity in acute ischemic stroke patients. Cureus. (2018) 10:e2870 10.7759/cureus.2870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tanne D, Molshatzki N, Merzeliak O, Tsabari R, Toashi M, Schwammenthal Y. Anemia status, hemoglobin concentration and outcome after acute stroke: a cohort study. BMC Neurol. (2010) 10:22. 10.1186/1471-2377-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Funduscopic imaging of Case 1.

Follow up of abnormal examination in Case 1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.