Abstract

Background

The Functional Impact of GLP-1 for Heart Failure Treatment (FIGHT) trial randomized 300 patients with HFrEF and a recent hospitalization for heart failure (hHF) to liraglutide versus placebo. While there was no difference in the primary outcome (rank score of time to death, time to re-hHF, and change in NT-proBNP), there was a significant increase in cystatin C among patients randomized to liraglutide raising concern of adverse renal outcomes. We performed a post-hoc analysis of FIGHT to investigate whether liraglutide was associated with worsening renal function (WRF).

Methods

The relationship between randomization to liraglutide and WRF was evaluated using logistic regression models. 274 patients (91%) had complete data to assess for WRF defined as: increase in SCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dl, or ≥ 25% decrease in eGFR, or an increase in cystatin C ≥ 0.3 mg/L from baseline to 180-days.

Results

Patients with WRF (n=113, 41%), compared to those without, were older, had more comorbidities, and lower utilization of guideline directed medical treatment (GDMT). Logistic models showed that age and baseline cystatin C levels were associated with WRF. In adjusted models, liraglutide was not associated with excess risk of WRF compared with placebo (odds ratio 1.02 [95% confidence interval 0.62–1.67]). There was also no difference in the rank score when WRF was added as a fourth-tier outcome.

Conclusions

Liraglutide was not associated with WRF among patients with HFrEF and a recent hHF. These data support the relative renal safety profile of liraglutide among HFrEF patients.

Registration

clinicaltrials.gov; Unique Identifier: NCT01800968

Glucagon Like Peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are recommended among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or with cardiovascular (CV) risk factors (Class 1, level of evidence A).1 Among the subgroup of patients enrolled in CV outcome trials of T2DM who had established heart failure (HF), GLP-1 RA’s had a neutral effect on the risk of hospitalization for HF (hHF).2 However, the safety and efficacy of GLP-1 RA on other clinical outcomes in patients with HFrEF have not been established.

The FDA highlights that nausea and vomiting which may be associated with liraglutide can cause worsening renal function (WRF). To date no large CV outcome trial of liraglutide versus placebo has suggested an increased risk of WRF.3–4 The Effect of Liraglutide, a Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Analogue, on Left Ventricular Function in Stable Chronic Heart Failure Patients with and without Diabetes (LIVE) and The Functional Impact of GLP-1 for Heart Failure Treatment (FIGHT) were two modest-sized trials that questioned the use of GLP-1RA in patients with HFrEF.5–6 LIVE, a trial designed to determine the effect of liraglutide on left ventricular function in patients with HFrEF, suggested that liraglutide may be associated with adverse cardiac events.6 FIGHT evaluated the efficacy and clinical stability of liraglutide versus placebo among patients recently discharged from hospitalization with HFrEF (both with and without T2DM).5 While the composite primary outcome was balanced between liraglutide and placebo groups, there was a significant increase in cystatin C from baseline to 180-days among patients randomized to liraglutide.5 Patients with HFrEF who are recently discharged from hospital are at increased risk for WRF.7 Furthermore, given major adverse effects of gastrointestinal upset, nausea, and poor oral tolerance, there is uncertainty regarding the renal safety of using GLP-1 RA immediately after hospitalization for HFrEF.

Given the potential for WRF associated with liraglutide, additional evaluation of the FIGHT trial was warranted in HFrEF patients recently hospitalized for acute HF.

Methods

FIGHT was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial designed to test the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of liraglutide among patients with HFrEF (LVEF ≤ 40% during the 3 months prior to study) and a recent HF hospitalization (within the prior 2 weeks) compared with placebo.5 The primary endpoint was a composite global rank score of time to death, time to rehospitalization for acute HF, and change in NT-proBNP level at 180-days compared to baseline. Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the primary endpoint, cardiac structure and function, 6-minute walk distance, and quality of life measures.

In the present post-hoc analysis, we evaluated the effects of liraglutide versus placebo on WRF in the FIGHT trial. Based on previously published terminology, the pre-specified definition of WRF was any one of the following: an increase in SCr ≥ 0.3 mg/dl; or ≥ 25% decrease in eGFR; or an increase in cystatin C ≥ 0.3 mg/L from baseline at 30-day, 90-day and 180-day visits.8 Change in serum creatinine alone is a marker of adverse CV outcomes but may not be a direct indicator of renal dysfunction.9–10 Hence, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with increase in serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dl but had a decline in eGFR > 25% or increase in serum creatinine > 50%.

Baseline demographics and characteristics among patients with and without WRF were determined. The change in baseline to follow up echocardiographic parameters (e.g. LVEDV/LVESV), 6-minute walk test, and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score among patients with WRF compared to those without were also determined. Multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed to ascertain baseline univariate and multivariate predictors of WRF. Inverse probability weighting methods were applied to account for missing data. The impact of adding WRF as a fourth-tier outcome to the composite global rank score was also calculated. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for the comparison of the modified rank score between liraglutide and placebo groups was conducted in order to maintain consistency with the FIGHT trial. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The trial design of FIGHT was approved by the institutional review boards of all the participating centers. The data, analytical methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Results

The present analysis included all 274 patients (91%) with available data for WRF. Patients with WRF (n=113, 41%) were more likely to be older, men, and had a greater number of comorbidities including history of ischemic heart disease, atrial flutter/fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and T2DM (Table 1). They were also less likely to be on guideline directed therapy treatment (GDMT) (Table 1). Patients with WRF, compared to those without WRF, had a greater numeric increase in LVEDV/LVESV, smaller interval decrease in NT-proBNP, and lower KCCQ scores at 180-days when compared to baseline (Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline demographics, characteristics, and change in measures from baseline to 180 days by WRF evaluating the association between WRF and change in cardiac function, renal function, and quality of life outcomes.

| Non-WRF (N=161) | WRF (N=113) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years: Median (25th-75th) | 59 (49 – 68) | 63 (55 – 67) | 0.04 |

| Male sex | 121 / 161 (75.2%) | 95 / 113 (84.1%) | 0.08 |

| White | 85 / 161 (52.8%) | 71 / 113 (62.8%) | 0.1 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| HF etiology: Ischemic | 128 / 161 (79.5%) | 98 / 113 (86.7%) | 0.12 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter history | 68 / 160 (42.5%) | 62 / 111 (55.9%) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 90 / 161 (55.9%) | 72 / 113 (63.7%) | 0.2 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 27 / 161 (16.8%) | 31 / 113 (27.4%) | 0.03 |

| Number HF hospitalizations >=1 in last year | 50 / 161 (31.1%) | 62 / 113 (54.9%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral edema >= 2+ versus < 2+ | 81 / 159 (50.9%) | 71 / 112 (63.4%) | 0.04 |

| Medications at enrollment | |||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 126 / 160 (78.8%) | 73 / 112 (65.2%) | 0.01 |

| Beta blockers | 155 / 161 (96.3%) | 101 / 113 (89.4%) | 0.02 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dl: Median (25th-75th) | 29 (22 – 42) | 35 (25 – 50) | 0.03 |

| Core lab cystatin C (mg/L): Median (25th-75th) | 1.33 (1.05 – 1.71) | 1.43 (1.15 – 1.83) | 0.1 |

| Change in measures from baseline to 180 days | |||

| Day 180 change from baseline LV end diastolic volume: Median (25th,75th), n | −6.0 (−34.0, 29.0), 82 | 14.5 (−30.0, 49.0), 58 | 0.09 |

| Day 180 change from baseline LV end systolic volume: Median (25th,75th), n | −2.0 (−35.0, 20.0), 82 | 1.5 (−31.0, 29.0), 58 | 0.18 |

| Day 180 change from baseline core lab NT-proBNP: Median (25th,75th), n | −104 (−892, 850.0), 115 | −54.0 (−1136, 1261), 79 | 0.92 |

| Day 180 change from baseline KCCQ Overall Summary score: Median (25th,75th), n | 17 (5, 31), 123 | 10 (−6, 32), 83 | 0.03 |

| Day 180 change from baseline walk distance (m): Median (25th,75th), n | 61 (2, 134), 104 | 46 (−29, 110), 62 | 0.18 |

| Day 180 change from baseline core lab cystatin C: Median (25th,75th), n | −0.11 (−0.29, 0.04), 116 | 0.18 (0.01, 0.39), 81 | <0.001 |

| Day 180 change from baseline GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2): Median (25th,75th), n | 5 (−2, 14), 120 | −8 (−18, 0), 85 | <0.001 |

| Day 180 change from baseline creatinine (mg/dL): Median (25th,75th), n | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.0), 120 | 0.3 (0.0, 0.5), 85 | <0.001 |

WRF indicates worsening renal failure.

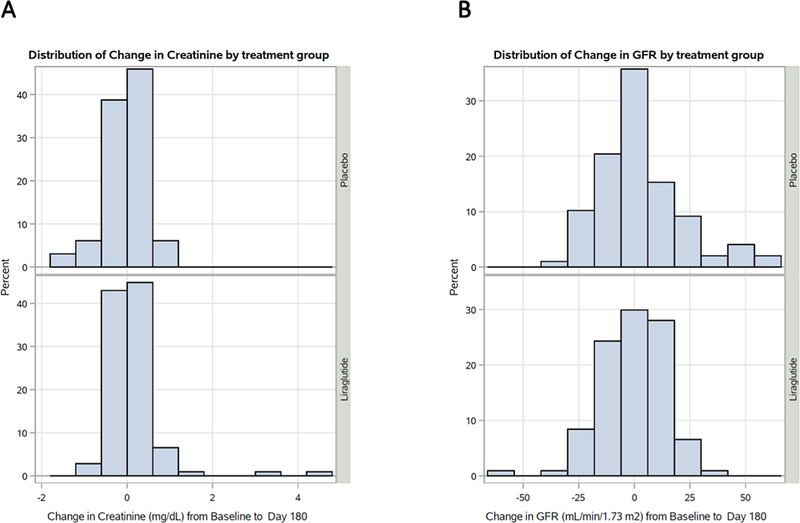

Based on multivariate logistic modeling, predictors of WRF included male sex (odds ratio [OR] 2.04 [95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–3.87], p-value 0.03) and higher baseline cystatin C levels (OR 1.55 [95% CI 1.01–2.39], p-value 0.05). For the overall study population, there was a balanced distribution of change in creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from baseline to 180 days (Figure 1). In both adjusted and unadjusted models, liraglutide was not associated with higher risk of WRF compared with placebo (unadjusted OR 1.02 [95% CI 0.62–1.67]; adjusted OR 1.09 [95% CI 0.68–1.77], respectively). In addition, incorporating WRF into the composite global rank score demonstrated no significant difference in the mean score (liraglutide 118 [standard deviation 72] versus placebo 130 [standard deviation 71], p-value 0.22). A sensitivity analysis using a more stringent definition of WRF, (a decline in eGFR > 25% or increase in serum creatinine > 50%), identified that patients with WRF, compared to those without WRF, still had a greater numeric increase in LVEDV/LVESV, smaller interval decrease in NT-proBNP, and lower KCCQ scores at 180-days when compared to baseline (Supplementary Material Table 1). Furthermore, the sensitivity definition of WRF demonstrated that liraglutide was not associated with increased risk of WRF (Supplementary Material Table 2).

Figure 1:

(A) distribution of change in creatinine (mg/dL) and (B) distribution of change in GFR (mL/min/1.73m2) from baseline to 180 days.

A comparison of BUN/Creatinine ratio at the end of follow-up showed similar results when liraglutide was compared to placebo (liraglutide mean: 22 [minimum 4.7, maximum 65]; placebo mean: 21.6 [minimum 4.7, maximum 93.8]). In contrast, a higher BUN/Creatinine ratio was observed in the WRF versus non-WRF group at the end of follow-up (WRF group mean: 25.1 [minimum 4.7, maximum 93.8]; non-WRF group mean: 19.5 [minimum 4.7, maximum 88.7]).

Discussion

Patients with HFrEF and recent hospitalization for acute HF are at increased risk of adverse CV and renal outcomes. The renal safety of GLP-1 RA initiated among patients with HFrEF remains uncertain. In the present study, we evaluated for an association between liraglutide and WRF in patients enrolled in the FIGHT trial. Our analysis demonstrated that (a) randomization to liraglutide was not associated with WRF, and (b) adding WRF to the composite global rank score did not yield significant differences in scores for patients receiving liraglutide versus placebo. Furthermore, there was no difference in BUN/Creatinine ratio when liraglutide was compared to be placebo. However, there was a numeric increase in BUN/Creatinine ratio in the WRF versus non-WRF group suggesting that volume status may be playing a significant role in the observed renal impairment.

The US FDA product label states that renal impairment is a potential risk of liraglutide.3 This is of potential concern due to growing use of GLP-1 RA with CV disease.11 Among patients with HFrEF, our results suggest that randomization to liraglutide was not associated with WRF. The LEADER trial previously demonstrated that liraglutide is safe to use in patients with T2DM and CV risk factors with improvement in CV and renal endpoints, irrespective of the FDA product label.4,12 A recent meta-analysis of seven large CV outcome trials of several different GLP-1RA in high-risk patients with T2DM also supports modest protection against progression to end-stage renal disease.13 The on-going FLOW trial (NCT03819153) will further evaluate the role of GLP-1 RA semaglutide versus placebo to reduce the risk of declining renal function.

The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines endorsed use of GLP-1 RA in patients with T2DM and HF.1 Liraglutide is also currently approved by the FDA for weight loss in patients with and without diabetes.3,14 As a result, liraglutide may be especially considered among patients with obesity and HF as a targeted treatment option for weight loss. A prior analysis of FIGHT demonstrated that liraglutide was associated with improved metabolic parameters and weight loss among patients with HFrEF.15 The present results suggest that initiation of liraglutide shortly after a hHF, as compared with placebo, is not associated with WRF among patients with HFrEF.

The most notable limitations of our analysis include those inherent to a post-hoc analysis. The increase in cystatin C levels seen in the liraglutide group when compared to placebo may be an indication of subtle changes in renal function that we are unable to measure based on the available data from FIGHT. Varying definitions of WRF may impact on the association of liraglutide versus placebo with WRF. However, a sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition did not change our primary findings.

Conclusions

Data from FIGHT demonstrates that there is no major renal impairment in patients with HF who are on liraglutide. Larger studies are needed to evaluate the renal outcomes of GLP-1 RA among patients with HFrEF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

The FIGHT trial was supported by research grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Vaduganathan is supported by the KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst (NIH/NCATS Award UL 1TR002541), serves on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Baxter Healthcare, Bayer AG, and Boehringer Ingelheim, and participates on clinical endpoint committees for studies sponsored by Novartis and the NIH. Dr. Greene is supported by a Heart Failure Society of America/ Emergency Medicine Foundation Acute Heart Failure Young Investigator Award funded by Novartis, receives research support from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis, and serves on an advisory board for Amgen. Dr. Sharma receives personal support from Fonds de La Recherche en Sante Quebec (FRSQ) – Junior 1 clinician scientist program, Bayer-Canadian Cardiovascular Society, Alberta Innovates Health Solution, Roche Diagnostics, Takeda, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Akcea.

References

- 1.Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri H V, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC, Piepoli MF, Birkeland KI, Adamopoulos S, Ajjan R, Avogaro A, Baigent C, Brodmann M, Bueno H, Ceconi C, Chioncel O, Coats A, Collet J-P, Collins P, Cosyns B, Di Mario C, Fisher M, Fitzsimons D, Halvorsen S, Hansen D, Hoes A, Holt RIG, Home P, Katus HA, Khunti K, Komajda M, Lambrinou E, Landmesser U, Lewis BS, Linde C, Lorusso R, Mach F, Mueller C, Neumann F-J, Persson F, Petersen SE, Petronio AS, Richter DJ, Rosano GMC, Rossing P, Rydén L, Shlyakhto E, Simpson IA, Touyz RM, Wijns W, Wilhelm M, Williams B, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, Huikuri H V, Johansson I, Jüni P, Lettino M, Marx N, Mellbin LG, Östgren CJ, Rocca B, Roffi M, Sattar N, Seferović PM, Sousa-Uva M, Valensi P, Wheeler DC, Windecker S, Aboyans V, Baigent C, Collet J-P, Dean V, Delgado V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2019; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlay SM, Givertz MM, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Chan M, Desai AS, Deswal A, Dickson VV, Kosiborod MN, Lekavich CL, McCoy RG, Mentz RJ, Piña IL. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America: This statement does not represent an update of the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA heart failure guideline update. Circulation. 2019;140:294–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/206321Orig1s000lbl.pdf. Revised Date: December 2014. Accessed Date 27 March 2020.

- 4.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Frandsen KB, Kristensen P, Mann JFE, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Pocock S, Poulter NR, Ravn LS, Steinberg WM, Stockner M, Zinman B, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margulies KB, Hernandez AF, Redfield MM, Givertz MM, Oliveira GH, Cole R, Mann DL, Whellan DJ, Kiernan MS, Felker GM, McNulty SE, Anstrom KJ, Shah MR, Braunwald E, Cappola TP. Effects of liraglutide on clinical stability among patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316:500–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jorsal A, Kistorp C, Holmager P, Tougaard RS, Nielsen R, Hänselmann A, Nilsson B, Møller JE, Hjort J, Rasmussen J, Boesgaard TW, Schou M, Videbæk L, Gustafsson I, Flyvbjerg A, Wiggers H, Tarnow L. Effect of liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue, on left ventricular function in stable chronic heart failure patients with and without diabetes (LIVE)—a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair JEA, Pang PS, Schrier RW, Metra M, Traver B, Cook T, Campia U, Ambrosy A, Burnett JC, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M. Changes in renal function during hospitalization and soon after discharge in patients admitted for worsening heart failure in the placebo group of the EVEREST trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2563–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damman K, Tang WHW, Testani JM, McMurray JJV. Terminology and definition of changes renal function in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3413–3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Vaccarino V, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Bradford WD, Horwitz RI. Correlates and impact on outcomes of worsening renal function in patients ≥65 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1110–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polonsky TS, Bakris GL. Heart Failure and Changes in Kidney Function: Focus on Understanding, Not Reacting. Heart Fail Clin. 2019;15:455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaduganathan M, Patel RB, Singh A, McCarthy CP, Qamar A, Januzzi JL, Scirica BM, Butler J, Cannon CP, Bhatt DL. Prescription of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists by Cardiologists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1596–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann JFE, Ørsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, Rasmussen S, Tornøe K, Zinman B, Buse JB. Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:839–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Sattar N, Preiss D, Køber L, Petrie MC, McMurray JJ V. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DCW, Le Roux CW, Ortiz RV, Jensen CB, Wilding JPH. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma A, Ambrosy AP, DeVore AD, Margulies KB, McNulty SE, Mentz RJ, Hernandez AF, Michael Felker G, Cooper LB, Lala A, Vader J, Groake JD, Borlaug BA, Velazquez EJ. Liraglutide and weight loss among patients with advanced heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction: insights from the FIGHT trial. ESC Hear Fail. 2018;5:1035–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.