Abstract

Background

Structured clinical assessments capture key information about performance that is rarely shared with the student as feedback. The purpose of this review is to describe a general framework for applying diagnostic score reporting within the context of a structured clinical assessment and to demonstrate that framework within dental hygiene.

Methods

The framework was developed using current research in the areas of structured clinical assessments, test development, feedback in higher education, and diagnostic score reporting. An assessment blueprint establishes valid diagnostic domains by linking clinical competencies and test items to the domains (e.g., knowledge or skills) the assessment intends to measure. Domain scores can be given to students as reports that identify strengths and weaknesses and provide information on how to improve.

Results

The framework for diagnostic score reporting was applied to a dental hygiene structured clinical assessment at the University of Alberta in 2016. Canadian dental hygiene entry-to-practice competencies guided the assessment blueprinting process, and a modified Delphi technique was used to validate the blueprint. The final report identified 4 competency-based skills relevant to the examination: effective communication, client-centred care, eliciting essential information, and interpreting findings. Students received reports on their performance within each domain.

Discussion

Diagnostic score reporting has the potential to solve many of the issues faced by administrators, such as item confidentiality and the time-consuming nature of providing individual feedback.

Conclusion

Diagnostic score reporting offers a promising framework for providing valid and timely feedback to all students following a structured clinical assessment.

Keywords: dental education, dental hygiene, diagnostic score reporting, feedback (learning), formative feedback, objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)

Abstract

Contexte :

Les évaluations cliniques structurées saisissent des renseignements clés sur la performance qui est rarement partagée avec les étudiants à titre de rétroaction. L’objectif de la présente étude est de définir une structure générale pour établir le suivi de la notation des diagnostics dans le cadre d’une évaluation clinique structurée et pour mettre en évidence ce cadre au sein de l’hygiène dentaire.

Méthodologie :

Le cadre a été créé à l’aide de la recherche actuelle dans les domaines d’évaluations cliniques structurées, d’élaboration de tests, de la rétroaction en éducation supérieure, et du suivi de la notation des diagnostics. Un plan d’évaluation détermine les domaines diagnostiques valides en liant les compétences cliniques et les éléments de tests aux domaines (p. ex., les connaissances ou les habiletés) que l’évaluation prévoit de mesurer. La notation des domaines peut être donnée aux étudiants sous forme de rapports qui précisent les forces et les faiblesses, et fournissent de l’information sur la façon de s’améliorer.

Résultats :

Le cadre de suivi de la notation des diagnostics a été appliqué à une évaluation clinique structurée en hygiène dentaire de l’Université de l’Alberta en 2016. Les compétences canadiennes d’entrée en pratique en hygiène dentaire ont guidé le processus de planification de l’évaluation et une technique modifiée de Delphi a été utilisée pour valider le plan. Le rapport final a ciblé quatre habiletés fondées sur des compétences, pertinentes à l’examen : communication efficace, soins axés sur le client, obtention des renseignements essentiels, et interprétation des constatations. Les étudiants ont reçu des rapports sur leur performance dans chaque domaine.

Discussion :

Le suivi de la notation des diagnostics a le potentiel de résoudre plusieurs des enjeux auxquels sont confrontés les administrateurs, comme la confidentialité des éléments et le temps demandé pour la rétroaction individuelle.

Conclusion :

Le suivi de la notation des diagnostics offre un cadre prometteur pour fournir une rétroaction valide et rapide à tous les étudiants à la suite d’une évaluation clinique structurée.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THIS RESEARCH.

Diagnostic score reporting helps students make important connections between dental hygiene competencies, their education, and their clinical practice.

Improving the feedback received during training may produce more mindful clinicians.

INTRODUCTION

This article is the second of 2 papers published in this issue that report on the development, implementation, and evaluation of a diagnostic score reporting framework for structured clinical assessments in dental hygiene. This review article examines the development and implementation components; an original research article1 presents the evaluation component, specifically how students responded to this novel feedback approach.

Structured clinical assessments (SCAs) are a necessary part of health education to ensure that students not only have knowledge but are able to apply this knowledge competently.2 The most common form of SCAs is the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), which involves multiple stations, each with a structured scenario portrayed by a standardized patient (a trained actor), and graded by qualified examiners who use a predetermined checklist of yes/no criteria.3- 6 Other SCAs, such as those seen in nursing or dental hygiene education, may involve a comprehensive single client interaction with a focus on interpersonal communication and health promotion.7- 10 Regardless of form or content, an SCA captures information on the achievement of competence in an objective and realistic manner.2-4

Despite the detailed information captured about the student in an SCA, this information is rarely communicated to the student as feedback.11 Time restrictions and test security are key issues. Providing feedback is a time-consuming endeavour requiring extensive faculty commitment,12-15 and feedback must be provided to students in a timely manner to be effective.13,16-19 Therefore feedback is either not provided11 or provided too late to have an impact.20 The development of a reliable and valid SCA is also labour intensive, thus similar examinations are reused across administrations, and these assessments are frequently high-stakes (i.e., they determine the ability to progress within the program).12 As such, there is a reasonable security concern that providing students with certain types of feedback, such as the assessment checklist itself, may contaminate future results and the validity of subsequent decision making.21,22 Novel approaches to providing feedback are required.

Diagnostic score reporting (DSR) presents a possible feedback framework for SCAs. DSR summarizes student performance on key domains of learning captured throughout the assessment, with an emphasis on encouraging improvements at the individual level.23,24

Domains reflect specific areas of knowledge, skill, and/or ability, so that student strengths and weaknesses can be readily identified.22-27 In keeping with best practices for communicating these results, reports should include clear and concise language, definitions of terms, esthetically pleasing designs, graphical representations of data, timely delivery, and cohort comparisons.23-26,28 These suggestions mirror the literature on providing quality feedback in higher education.

DSR overcomes the major barriers presented by SCAs. Structuring feedback by diagnostic domains allows performance to be analysed without revealing the test items to students (i.e., test security is maintained). The predetermined structure helps to facilitate timely feedback, which can be further improved using electronic grading to provide near-instant feedback via online platforms. Improving efficiency would allow all students to receive diagnostic information without drastically increasing the time demands placed on instructors.

DSR has been primarily used for large-scale assessments,22,24,26,28,29 with scarce, literature on applying the framework to smaller scale testing scenarios such as dental or dental hygiene SCAs. Research on feedback with some elements of DSR is slowly emerging in the health literature.20,30,31 However, a common methodology for developing valid diagnostic domains and quality reports has not been established. For example, Taylor and Green20 developed domain-based feedback for their medical SCA by mapping test items to a nationally defined competency,32 but they did not provide the feedback in a timely manner, nor did they appear to provide suggestions for improvement. As a result, their feedback had little impact on student learning. Establishing a practical DSR framework for SCAs could guide educators to provide high-quality feedback.

The objectives of this project were to 1) describe a general framework for applying DSR within the context of an SCA, in order to provide valid and quality feedback to students; and 2) to implement that framework within a small-scale dental hygiene SCA.

METHODS

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Office (Pro00062297).

A literature review was conducted in the areas of structured clinical assessments, test development, feedback in higher education, and diagnostic score reporting. Key findings were condensed into a practical framework for providing feedback following an SCA. A template report was then created, validated, and implemented using this framework.

Framework for diagnostic score reporting

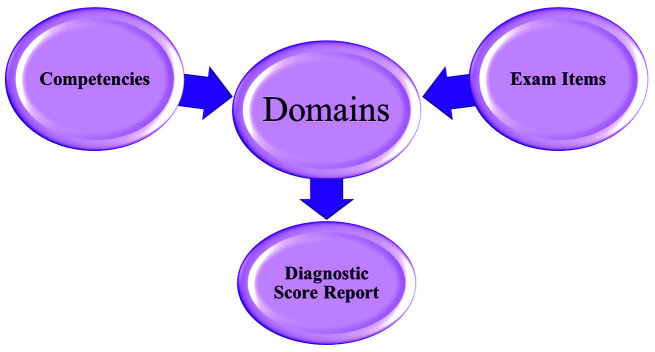

The 2 major elements of DSR are 1) establishing valid diagnostic domains through assessment blueprinting; 2) translating that information to students through effective reports. Finally, an evaluation component is required to ensure DSR is meeting its objectives.

Assessment blueprinting

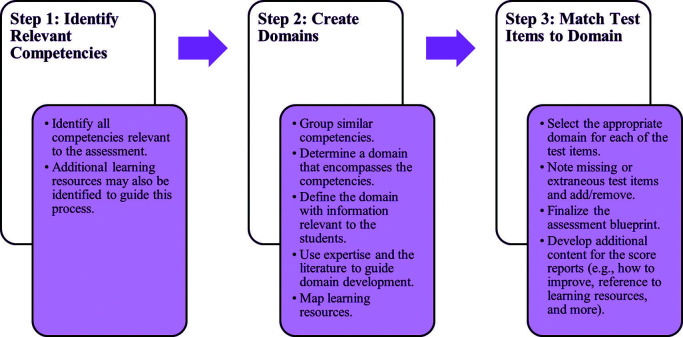

An assessment blueprint links the purpose of the assessment, the domains being assessed, and the test items measuring those domains.22,33,34 Supporting evidence is also provided to validate those links. Although assessments are typically designed based on course objectives (knowledge, skills, and attributes taught within the course), this article demonstrates how assessments can be linked to overarching competencies of the profession where some required skills and knowledge extend beyond courses. A top-down approach to competency blueprinting within the context of an SCA is illustrated in Figure 1, adapted from the evidence-centred design method of test development.34

The first step in this process is to identify all competencies relevant to the assessment based on the test specifications (the purpose of the test).33 Competencies are then grouped into domains based on similarity or themes using a form of iterative thematic analysis.35 Domains for large assessments often focus on specific areas of knowledge24 (e.g., a specific disease), however an SCA may require different types of knowledge to be grouped together under specific skills (e.g., identifying contraindications), keeping in mind that each domain must be assessed by multiple test items. Developers are encouraged to review the literature and use their expertise, the goal of the assessment, the number of test items, and the student perspective to determine the most appropriate groupings (e.g., by knowledge area, skill or cognitive hierarchy).23,26 The domains are defined by the overarching theme of the grouped competencies.

Each test item is then mapped to the most appropriate domain. There should be several test items representing a single domain, with more items increasing the domain’s reliability.36 A delicate balance must be struck between reliability (having enough test items within each domain to reliably calculate a score) and specificity (having a domain specific enough that the student finds the information useful).26 As psychometric reliability can be difficult to achieve in small-scale testing, this article focusses on content validity while the practical implications are reviewed in our companion paper.1

For a more detailed explanation of blueprint development, please refer to The Handbook of Test Development.33,34 The assessment blueprint forms the main structure of DSR (Figure 2). Domain scores for the student reports are generated by the number of test items they successfully complete within that domain.

The final blueprint should be externally validated to ensure accuracy. One such method is the Delphi technique37, an iterative survey-based approach to reaching consensus among multiple experts. In this technique, several experts independently evaluate the results of the qualitative analysis (the blueprint) by using a numeric rating scale. The blueprint is then adapted until the average/median ratings of the experts are acceptably high based on a predetermined criterion. This method is favoured because of its use of both expert opinions and an objective measure of success.

Report creation

After the assessment blueprint is developed, the next step is to determine what output to provide students as feedback. There are a variety of ways to present information to students, particularly with electronic media, but a minimum number of fundamental components should be included. The purpose of the SCA overall, and the domains individually, should be clearly defined.23-26,28 Information on how to improve within each domain should also be included, such as references to textbooks and other learning resources, and/or ways to interpret and use the feedback to improve performance.23,24,36 Performance markers such as cohort comparisons or comparisons to expected levels of achievement may help students better comprehend their results.26 Where appropriate, developers should include graphs, colour, headings, and white space to increase report useability.23-26,28

Figure 1.

Assessment blueprinting process for diagnostic score reporting

Figure 2.

Framework for diagnostic score reporting

Evaluation

Following implementation of DSR, an evaluation component is necessary to ensure that the content of these reports is not only theoretically valid but also practically useful. Much of the score reporting literature focuses on assessing the usability and interpretability of these reports by stakeholders (in this case the students), which may involve a survey-based approach to gathering student opinions and appraising their understanding of their reports.26 However, the literature on feedback in higher education goes further to suggest that, if the ultimate goal of feedback is to improve student learning, then student outcomes (e.g., impact on performance) must be assessed.38 As this is such a key step in the process of producing quality feedback, it is described in greater detail in our companion paper.1

Implementing the framework for diagnostic score reporting

The DSR framework described above was applied to a dental hygiene SCA at the University of Alberta in 2016. This history-taking SCA was a comprehensive single client assessment, where students applied their interpersonal communication skills to establish a rapport, conduct a full health and dental history, and identify any risk factors contraindicating or requiring modifications to dental hygiene therapy. The SCA was evaluated using a grading checklist of observable items, such as key messages the student is required to communicate to the client (e.g., offering to provide tobacco cessation strategies), marked yes or no. There were also rating scales to assess global skills used throughout the interaction (e.g., organization and communication). The dental hygiene history-taking SCA assessed a variety of essential practitioner skills. However, feedback had been previously limited due to time demands and test item confidentiality. DSR offered a feasible strategy to provide all students with feedback.

A modified Delphi approach (dictated by expert availability) was used to validate the assessment blueprint. Four dental hygiene clinical instructors were asked to independently rate the appropriate level of fit of the competencies and test items within each diagnostic domain based on a 5-p,oint scale (no fit to excellent fit) (Appendix A). Additional space was available for raters to make comments. Any item that received a median score of 3 or lower was reviewed. Changes were made to the blueprint where appropriate.

RESULTS

Assessment blueprinting

Two researchers (AC & AS) followed the blueprinting process described above, guided by the Canadian dental hygiene entry-to-practice competencies.39 Note that the Canadian competencies for baccalaureate dental hygiene programs40 were also available but not used because the University of Alberta had a diploma exit option at the time of the study and most other dental hygiene programs did not offer a bachelor’s degree. As a result, the entry-to-practice competencies seemed more generalizable.

After the researchers reconciled discrepancies through discussion and consensus, 4 competency-based skills were identified in the blueprinting process: 1) effective communication; 2) client-centred care; 3) eliciting essential information; and 4) interpreting findings.

Further modifications to the blueprint were made following the validation process using a modified Delphi technique. Regarding each item’s fit within its assigned domain, the raters gave 2 competencies and 3 test items a median score of 3 or lower. AC & AS reviewed the items and, with the help of the raters’ comments, adjusted the blueprint. Specifically, 1 competency and 2 test items were moved to a more appropriate domain and the definition of 1 domain was made more inclusive.

Table 1 presents the final assessment blueprint, including domain definitions, relevant competencies, and examples of test items (for security reasons actual test items are not provided).

Report creation

The DSR output included all the information from the blueprint (excluding the test items), as well as course expectations, cohort comparisons, and information on how to improve. Best practices of effective score reporting were followed.25 Timeliness was facilitated by making the reports available to students online. Since the SCA was graded using iPads, domain scores were automatically calculated once results were submitted.

Table 1.

Assessment blueprint for a dental hygiene structured clinical assessment

|

Domain |

Definition |

Competencies |

Test items |

|

Effective communication |

This skill emphasizes how you are communicating, as opposed to what is being said. Effective communication strategies make the client feel safe and comfortable. It also means providing information in an appropriate manner that the client can follow and understand. |

Use effective verbal, non-verbal, visual, written, and electronic communication. Demonstrate active listening and empathy to support client services. Select communication approaches based on clients’ characteristics, needs, and linguistic and health literacy level. Facilitate confidentiality and informed decision making in accordance with applicable legislation and code of ethics. Convert findings in a manner relevant to clients using the principles of health literacy. Manage time and other resources to enhance the quality of services provided. Create an environment in which effective learning can take place. |

2 checklist items and 3 rating scales Example: “Establishes rapport with client” |

|

Client-centred care |

This skill emphasizes how well you have incorporated the client in the care discussions and decisions. Client-centred care means respecting the needs, opinions, and autonomy of the client. |

Respect the autonomy of clients as full partners in decision making. Respect diversity in others to support culturally sensitive and safe services. Design and implement services tailored to the unique needs of individuals. Consider the views of clients about their values, health, and decision making. Work with clients to assess, diagnose, plan, implement, and evaluate services for clients. Prioritize clients’ needs through a collaborative process with clients. Negotiate mutually acceptable individual or program learning plans with clients. Select educational interventions & develop educational materials to meet clients’ learning needs. |

5 test items and 1 rating scale Example: “Addresses the client’s chief concern” |

|

Eliciting essential information |

This skill emphasizes what you are asking. Eliciting essential information from the client involves using appropriate prompts and follow-up questions to collect all necessary information prior to starting dental hygiene therapy. Comprehensive questioning is needed to identify status and risks of both oral and overall health. |

Collect accurate and complete data on the general, oral, and psychosocial health status of clients. Elicit information about the clients’ oral health knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and skills as part of the educational process. Assess clients’ need to learn specific information or skills to achieve, restore, and maintain oral health and promote overall well-being. |

10 checklist items Example: “Asks the client about current medications” |

|

Interpreting findings |

This skill emphasizes how accurately you analyse the information revealed by the client. Proper interpretations include making appropriate modifications to the dental hygiene appointment, providing accurate recommendations, and identifying contraindications to care. |

Apply principles of risk reduction for client safety, health, and well-being. Evaluate clients’ health and oral health status using determinants of health and risk assessment to make appropriate referral(s) to other health care professionals. Apply theoretical frameworks to the analysis of information to support practice decisions. Apply evidence-based decision making to the analysis of information and current practices. Apply the behavioural, biological, and oral health sciences to dental hygiene practice decisions. Identify clients for whom the initiation or continuation of treatment is contraindicated based on the interpretation of health history and clinical data. Identify clients at risk for medical emergencies. Formulate a dental hygiene diagnosis using problem solving and decision-making skills to synthesize information. Provide recommendations in regard to clients’ ongoing care including referrals when indicated. |

8 checklist items Example: “Recognizes the need for a medical consult prior to dental hygiene treatment” |

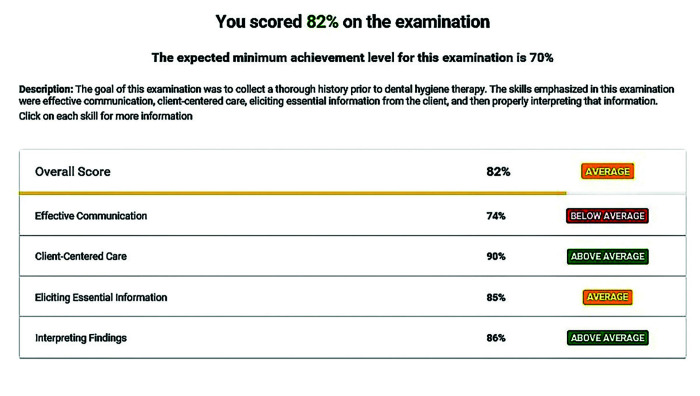

Figure 3.

Sample diagnostic score reporting output, initial page

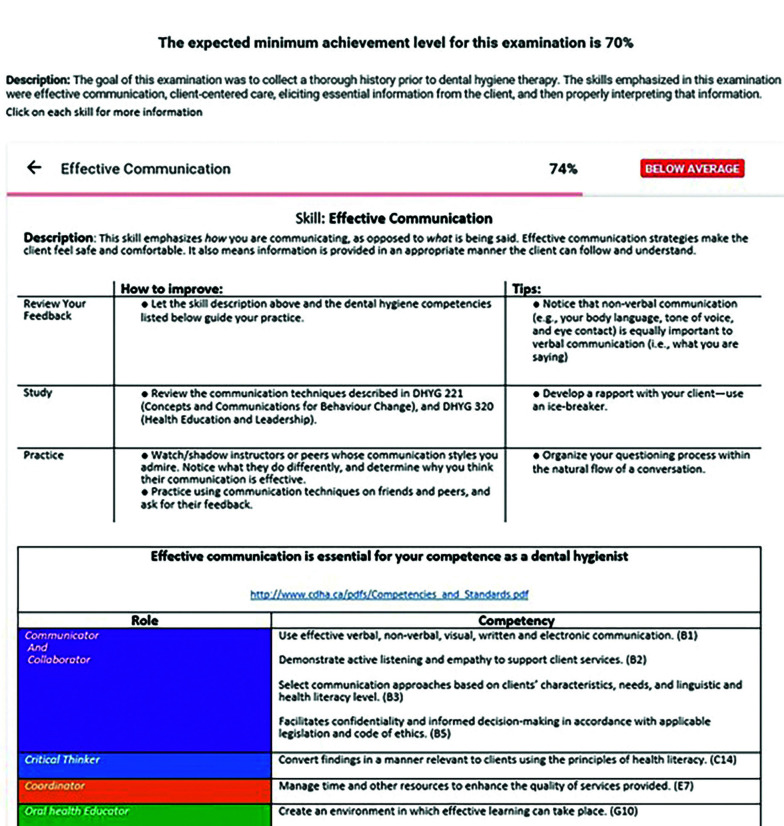

Figure 4.

Sample diagnostic score reporting output for a diagnostic domain

The first page of the student report showed their overall score on the SCA and their scores for each diagnostic domain (Figure 3). Their overall score was compared to the passing grade of 70%, and domain scores were compared to the performance of their peers, described as below average, average or above average (based on a fixed mathematical formula which placed the “average” category within plus or minus one-half standard deviation around the mean score). This method was chosen because the majority of students pass this assessment and thus having a second comparison marker relative to their peers might encourage students to improve their performance beyond simply striving to pass. However, other comparison methods may be more appropriate depending on the pass/fail rate of the assessment and the objectives of the feedback. For example, focusing on performance indicators relative to the “just passing” group could alert failing students and students at risk of failing that they need to improve in that area.31

Students were prompted to click on each of the diagnostic domains to receive more information. Domain-specific pages displayed the definition of that skill, information on how to improve, and the relevant dental hygiene competencies. The domain-specific output for effective communication is presented in Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

SCAs are a common assessment method in health education, capturing detailed information on clinical skills. However, the opportunity to share this information with students as feedback tends to be neglected.11 DSR offers a possible framework for providing feedback to students, describing test performance by the underlying domains of learning the test intends to measure and including resources for making individual-level improvements.23-26 As such, this research project sought to establish and apply a general framework for providing DSR within the context of an SCA.

Piloting DSR in the dental hygiene program demonstrated how score reports could be generated efficiently and without revealing the actual test items, maintaining test security. Only a moderate initial time investment was required, after which all students received feedback. However, these reports included only the most basic elements of DSR and could be modified to improve and maximize the feedback.

Reports could provide direct links to sections of textbooks or other online documents that may aid student learning.24,28 Links to video-based feedback could also be provided, either using trained professionals to demonstrate important interactive skills, or the student’s own video performance for self-review.41,41-43 Further personalization and individualization may also be beneficial. Although the first page of each student’s report differed based on their performance, indicating their strengths and weaknesses, the information provided on the domain pages was the same for all students. A next step may be to have different information displayed on each student’s domain pages, reflecting the test items that were incorrect and, thus, more acutely, where to focus their learning. Having the basic framework in place will allow improvements to be made year after year without placing a significant time burden on the test administrator.

A limitation of this study is that the Delphi technique typically involves a minimum of 7 to 10 expert opinions, which was not feasible given the small number of clinical instructors in our program. Furthermore, following the modifications to the blueprint, ideally a second round of expert ratings should have been conducted. However, weighing instructor availability against the small number of changes made to the blueprint, this second round was forgone. Consequently, this study refers to a “modified” Delphi technique to acknowledge these limitations. Another limitation is that this article does not describe psychometric techniques to ensure domain reliability, focusing more on user-friendly methods to provide valid feedback.

The main strength of this study is the evidence-based premise in developing resources for assessment and reporting of student performance based on competencies of the profession. The reporting process described above was based on a multidisciplinary literature review across several key factors for providing valid feedback. However, for feedback to be of quality, it must be both valid and practically usefully—i.e., it must have some impact on student learning. Our companion paper describes the effect of providing DSR following a dental hygiene SCA.1

CONCLUSION

DSR offers a promising framework for providing feedback following an SCA in a timely manner while upholding test confidentiality. This article can guide readers to develop diagnostic domains and provide students with validated score reports.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare they have no financial, economic or professional interests that may have influenced the design, execution or presentation of this scholarly work.

APPENDIX

Footnotes

CDHA Research Agenda category: capacity building of the profession

REFERENCES

- 1. Clarke A, Lai H, Sheppard ADE, Yoon MN Effect of diagnostic score reporting following a structured clinical assessment of dental hygiene student performance Can J Dent Hyg 2021;55(1):39-47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller GE The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance Acad Med 1990;65(9):S63–S67 2400509 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harden RM, Stevenson M, Downie WW, Wilson GM Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination Br Med J 1975;1(5955):447–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harden RM, Gleeson FA Assessment of clinical competence using an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) Med Educ 1979;13(1):39–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Harden R What is an OSCE? Med Teach 1988;10(1):19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Newble D Techniques for measuring clinical competence: Objective structured clinical examinations Med Educ 2004;38(2):199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitchell ML, Henderson A, Groves M, Dalton M, Nulty D The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE): Optimising its value in the undergraduate nursing curriculum Nurse Educ Today 2009;29(4):398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rushforth HE Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE): Review of literature and implications for nursing education Nurse Educ Today 2007;27(5):481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blue C Objective structured clinical exams (OSCE): A basis for evaluating dental hygiene students’ interpersonal communication skills Access 2006;20(7):27–31 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walker K, Jackson RD, Maxwell L The importance of developing communication skills perceptions of dental hygiene students J Dent Hyg 2016;90(5):306–312 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harrison CJ, Molyneux AJ, Blackwell S, Wass VJ How we give personalised audio feedback after summative OSCEs Med Teach 2015;37(4):323–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. White CB, Ross PT, Gruppen LD Remediating students’ failed OSCE performances at one school: The effects of self-assessment, reflection, and feedback Acad Med 2009;84(5):651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Archer JC State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback Med Educ 2010;44(1):101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hendersen M, Ryan T, Phillips M The challenges of feedback in higher education Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2019;44(8):1237–1252 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wardman M, Yorke VC, Hallam JL Evaluation of a multi-methods approach to the collection and dissemination of feedback on OSCE performance in dental education Eur J Dent Educ 2018;22(2):e203–e211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ende J Feedback in clinical medical education JAMA undefined1983;250(6):777–781 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sadler DR Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2010;35(5):535–550 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rust C The impact of assessment on student learning: How can the research literature practically help to inform the development of departmental assessment strategies and learner-centred assessment practices? Active Learning in Higher Education 2002;3(2):145–158 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quinton S, Smallbone T Feeding forward: Using feedback to promote student reflection and learning—a teaching model Innovations in Education and Teaching International 2010;47(1):125–135 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taylor CA, Green KE OSCE Feedback: A randomized trial of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and student satisfaction Creative Education 2013;4(6):9 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gotzmann A, De Champlain A, Homayra F, et al. Cheating in OSCEs: The impact of simulated security breaches on OSCE performance Teach Learn Med 2017;29(1):52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bulut O, Cutumisu M, Aquilina AM, Singh D Effects of digital score reporting and feedback on students’ learning in higher education Front Educ 2019;4(65) [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roberts MR, Gierl MJ Developing score reports for cognitive diagnostic assessments Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 2010;29(3):25–38 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goodman DP, Hambleton RK Student test score reports and interpretive guides: Review of current practices and suggestions for future research Applied Measurement in Education 2004;17(2):145–220 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts MR, Gierl MJ.Development of a framework for diagnostic score reporting. Paper presented at the annual meeting of theAmerican Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA, USA,2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zenisky AL, Hambleton RK Developing test score reports that work: The process and best practices for effective communication Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice 2012;31(2):21–26 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zapata-Rivera JD, Katz IR Keeping your audience in mind: Applying audience analysis to the design of interactive score reports Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 2014;21(4):442–463 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trout DL, Hyde E.Developing score reports for statewide assessments that are valued and used: Feedback from K-12 stakeholders. Paper presented at the annual meeting of theAmerican Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, USA,2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Park YS, Morales A, Ross L, Paniagua M Reporting subscore profiles using diagnostic classification models in health professions education Eval Health Prof2019:163278719871090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brown G, Manogue M, Martin M The validity and reliability of an OSCE in dentistry Eur J Dent Educ 1999;3(3):117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harrison CJ, Könings KD, Molyneux A, Schuwirth LW, Wass V, van der Vleuten CP Web-based feedback after summative assessment: How do students engage? Med Educ 2013;47(7):734–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.General Medical Council.Tomorrow’s doctors: Outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education.Manchester, UK:General Medical Council;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wise LL, Plake BS.Test design and development following the standards for educational and psychological testing. In: Lane S, Raymond MR, Haladyna TM, eds. Handbook of test development. 2nd ed.New York, NY:Routledge;2015: 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Risconscente MM, Mislevy RJ, Corrigan S.Evidence-centered design. In: Lane S, Raymond MR, Haladyna TM, eds. Handbook of test development. 2nd ed.New York, NY:Routledge;2015: 40–63. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hanson EC Analysing qualitative data In: Successful qualitative health research: A practical introduction.New York, NY:Open University Press;2006: 137– 60 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sinharay S, Puhan G, Haberman SJ Reporting diagnostic scores in educational testing: Temptations, pitfalls, and some solutions Multivariate Behavioral Research 2010;45(3):553–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hsu C-C, Sandford BA The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation 2007;12(10):1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boud D, Molloy E What is the problem with feedback? In: Boud D, Molloy E, eds. Feedback in higher and professional education: Understanding it and doing it well.New York, NY:Routledge;2013 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA), Federation of Dental Hygiene Regulatory Authorities (FDHRA), Commission on Dental Accreditation of Canada (CDAC), National Dental Hygiene Certification Board (NDHCB), Dental Hygiene Educators of Canada (DHEC).Entry-to-practice competencies and standards for Canadian dental hygienists.Ottawa, ON:CDHA;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canadian Dental Hygienists Association (CDHA).Canadian competencies for baccalaureate dental hygiene programs.Ottawa, ON:CDHA;2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paul S, Dawson K, Lanphear J, Cheema M Video recording feedback: A feasible and effective approach to teaching history-taking and physical examination skills in undergraduate paediatric medicine Med Educ 1998;32(3):332–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukkink RG, Trienekens N, Kramer LJ Video feedback in education and training: Putting learning in the picture Educ Psychol Rev 2011;23(1):45–63 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Massey D, Byrne J, Higgins N, Weeks B, Shuker M-A, Coyne E, et al. Enhancing OSCE preparedness with video exemplars in undergraduate nursing students. A mixed method study Nurse Educ Today 2017;54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.