Abstract

The gender-transformative approach to health promotion in the United States and globally has been central to defining gender as a determinant of health and advancing health programs, services, and policies that respond to gender-based inequities. However, current gender frameworks are built on historical perspectives that center cisgender people's experiences and reinforce the gender binary. This restricted focus does not respond to health inequities experienced by transgender people—to the detriment of health programs, services, and policies. As transgender people's health and rights continue to garner attention in movements across health services and policy spaces, it is crucial for frameworks to be expansively redefined to achieve truly transformative gender equality and equity for all gender identities and expressions.

Keywords: cisgender, gender equality, gender equity, gender inclusivity, transgender

Introduction

Recent gender-based movements in the United States and globally have brought the issue of long-standing gender power imbalances to the fore of science and social discourse alike.1 For example, the increasing visibility of transgender (trans) movements in health services and policy spaces highlights a need to address inequities among trans populations, including nonbinary populations. This visibility calls for gender-transformative solutions, defined as those that actively challenge gender norms and address power inequities between different genders,2 to achieve health equity.3 However, these advances have largely been pertinent in combating inequities for cisgender (cis or nontrans) people.4 In tandem with these gender-based initiatives, the recent proliferation of trans health literature has made visible the persistent and unmet needs of trans people across health care services, programs, and policies. In this perspective, we offer an updated framework to address this moral and scientific imperative in public health. Our purpose is to propose an expansive gender equity continuum framework that promotes health equity and solutions for meeting trans people's needs in health care services, programs, and policies.

A Homage to Health Equity and Gender-Transformative Continuum Frameworks

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services describes health equity in Healthy People 2020 as the attainment of the highest level of health for all people.5 Recently, scholars have expanded this framework to highlight three components: “(a) valuing of all individuals and populations equally,” “(b) recognizing and rectifying historical injustices,” and “(c) providing resources according to need—not equally, but according to need.”5 In efforts to apply an equity lens at the intersection of gender and health, a gender-transformative continuum model was previously proposed—calling for “sensitive, transformative, and empowering approaches to gender and sexuality” in health promotion, which was later supported by WHO's evidence of gender as a key determinant of health.2,6

The WHO's Gender Responsiveness Scale (GRS), shown in Table 1,6 originally posited that health programs, services, and policies can either exploit, accommodate, or transform systems by examining and changing gender norms, roles, and relations toward the goal of gender equity for cis women and men (without attention to trans persons). It described five levels in which programs, services, and policies can fall: (1) gender-unequal, which perpetuates gender and sex-based inequalities; (2) gender-blind, which ignores gender norms, roles, and relations; (3) gender-sensitive, which recognizes gender inequities without remedial actions; (4) gender-specific, which targets specific groups of women or men to achieve or meet certain needs; and (5) gender-transformative, which fosters changes in power relationships between women and men.2 This model pushes programs, services, and policies to move beyond acknowledging gender inequalities between cis men and cis women to actively address the root causes of these inequalities such as gender power dynamics and differential access to resources. Positive examples can be seen in the global sexual and reproductive health programming that address negative aspects of masculinity to combat HIV and violence against women,7 as well as in policy and budgeting spaces where governments have removed primary school fees to encourage girls participation or provided paid maternity and paternity leave to encourage men's involvement in child rearing.4

Table 1.

World Health Organization's Gender Responsive Assessment Scale: Criteria for Assessing Programs and Policies

| Levels | Description |

|---|---|

| Level 1: Gender-unequal | • Perpetuates gender inequality by reinforcing unbalanced norms, roles, and relations, and privileging men over women (or vice versa) |

| Level 2: Gender-blind | • Ignores gender norms, roles, and relations, and differences in opportunities and resource allocation for women and men |

| Level 3: Gender-sensitive | • Does not address inequality generated by unequal norms, roles or relations, and indicates gender awareness, although often no remedial action is developed |

| Level 4: Gender-specific | • Considers women's and men's specific needs by intentionally targeting and benefiting a specific group of women or men to achieve certain policy or program goals or meet certain needs |

| Level 5: Gender-transformative | • Addresses the causes of gender-based health inequities and includes strategies to foster progressive changes in power relationships between women and men |

The Need to Expand Gender Equity Framework to Embrace Trans Populations

To move toward gender equity, there is a need for organizations and policies to adopt models that explicitly value, recognize, and provide resources to trans populations. It is well documented that trans people worldwide experience multiple forms of social and economic injustices that are linked to gender and health,8,9 such as gender-based violence (GBV); mental health problems; disparities in access to appropriate sexual health services (including youth-targeted services such as pubertal suppression and cross-sex hormone therapies); scarcity in clinicians with experience in gender diversity, discrimination, and stigma; limited access to higher education; gender pay/wage gap; workplace sexual harassment; and unemployment. These inequities are particularly salient among historically disadvantaged groups such as racially or ethnically diverse groups and those residing in underserved settings.

However, high-impact health programs, services, and policies seeking to mainstream elimination of gender-based health inequities continue to exclude trans people. A global report found that among organizations identified to be active in health promotion (n=198), 95% do not define trans populations in their definition of gender, 93% do not recognize trans people in their commitment to gender equality, and 92% do not refer to trans health in their programmatic services.9 A recent review of gender transformative programming aimed at improving the health of young people found that none of the reviewed programs focused on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or other gender-diverse populations.10

Near-universal exclusion of trans populations from existing health paradigms is a blind spot in health services and policy spaces that reinforces a binary definition of gender in health programming, services, and policies (i.e., that cis men and cis women are mutually exclusive and exhaustive gender categories). Health programs, services, and policies delivered under these paradigms may propagate cis norms that do not resonate with many trans persons and can systematically misdeliver and impede the provision of critical health services. Trans populations may be unable to obtain essential care such as cancer screenings, mammography tests, Pap tests, prostate-related tests, pregnancy wellness, family planning, and GBV services, as these services are often delivered under models that cannot see beyond cis people's bodies.8 For example, trans men and nonbinary individuals with cervixes and need appropriate screenings may experience discrimination and rejection from clinics that only recognize these services for cis women.11

Toward an Expansive Gender Equity Continuum Model

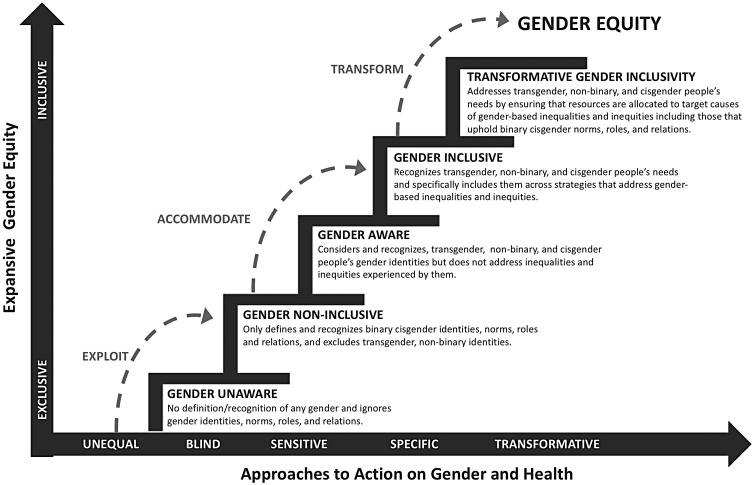

To make trans people explicitly visible in health programs, services, and policies, we propose an expansive gender equity continuum model (Fig. 1). This model expands the WHO's GRS,6 which defines equity on a continuum from gender unequal to gender transformative, to include an additional dimension of gender expansive from exclusive (i.e., considers and recognizes cisgender identities only) to inclusive (i.e., considers and recognizes trans people, including people with nonbinary gender identities). By identifying these independent axes, this model recognizes that a programmatic or policy approach to gender and health could be highly transformative (i.e., addresses the causes of gender inequity) but may fail to be equitable noncisgender populations, as we have argued is the case for many existing programs and policies. Alternatively, a program or policy can be inclusive yet promote practices that are merely sensitive but not truly transformative. For example, this may include a program that delivers quality health services to cisgender and trans populations but does not address underlying causes of gender-based health services inequities such as lack of health insurance coverage for hormone therapy or gender affirmation surgery. The proposed model, therefore, retains the previous model and adds a critical component of gender inclusivity2,6—pushing the field of gender and gender-based health program, services, and policies toward expansive gender equity.

FIG. 1.

Expansive gender equity continuum. Note: This expansive gender equity continuum is inspired by previous studies of Pederson et al.2 and the World Health Organization6 frameworks of continuum approach to action on gender and health.

We provide the following examples of how this updated framework might be implemented in practice to improve upon programs, services, and policies that have historically overlooked trans populations:

-

1.

Microlevel: Solicit, prioritize, and incorporate feedback from diverse trans stakeholders to identify blind spots (e.g., unmet health care needs, barriers to care, lack of representation in health services and policy spaces, etc.) and improve social, physical, and political accessibility to care in community-based organizations, clinics, and research organizations. Inquire and document trans people's experiences with health care services.

-

2.

Mesolevel: Remove explicit and implicit binary sex-based labeling of routine health care services (e.g., mammography, cervical screening, colonoscopy, HIV testing, and intrauterine devices). Implement staff trainings regarding the unique clinical considerations of diverse trans individuals who are seeking these services.

-

3.

Macrolevel: Apportion, keep records of, and further tailor funding for health programs and services geared explicitly toward racially/ethnically diverse trans individuals, as is already done for cis women and cis men of color. Adapt and conspicuously display explicit antidiscrimination policies specific to gender identities and expression.

Conclusion

To truly achieve gender equity, it is vital for gender-transformative approaches to be explicit and intentional in including diverse gender identities and presentations in policies, practices, organizational cultures, and data. Our proposed expansive gender equity continuum model provides a framework for health researchers, programmers, and policy makers to address gender-based health inequities for trans people's needs in health care services, programs, and policies. By adapting our expansive gender equity continuum model, trans people's experiences of gender-based inequities and health needs are explicitly recognized and integrated in services, programmatic and policy strategies, and solutions. Moreover, achieving gender equity must include being intentional in committing to eradicating gender inequities across the continuum, particularly those experienced by historically disadvantaged communities. It starts by encouraging health care services, programs, and policies to redefine and expand their concept of gender, to explicitly detail strategies that cause gender inequities, and to allocate resources for those strategies.

Abbreviations Used

- GBV

gender-based violence

- GRS

Gender Responsiveness Scale

Authors' Contribution

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, writing, and editing of this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the authors' affiliated entities, namely, Brown University, The Foundation of AIDS Research, and Johns Hopkins University.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: Restar AJ, Sherwood J, Edeza A, Collins C, Operario D (2021) Expanding gender-based health equity framework for transgender populations, Transgender Health 6:1, 1–4, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0026.

References

- 1. Messerschmidt JW, Messner MA, Connell R, Martin PY. Gender Reckonings: New Social Theory and Research. New York, NY: NYU Press, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pederson A, Greaves L, Poole N. Gender-transformative health promotion for women: a framework for action. Health Prom Int. 2014;30:140–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta GR. Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: the what, the why, and the how. HIV/AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2000;5:86–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heymann J, Levy JK, Bose B, et al. Improving health with programmatic, legal, and policy approaches to reduce gender inequality and change restrictive gender norms. Lancet. 2019; 393:2522–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services, & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Gender Mainstreaming for Health Managers: A Practical Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pulerwitz J, Barker G, Segundo M, Nascimento M. Promoting more gender-equitable norms and behaviors among young men as an HIV/AIDS prevention strategy. Washington, DC: Population Council Inc, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388:412–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Global Health 50/50. The Global Health 50/50 report 2019: Equality works. London, United Kingdom: Global Health 50/50, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Levy JK, Darmstadt GL, Ashby C, et al. Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8:e225–e236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDowell M, Pardee DJ, Peitzmeier S, et al. Cervical cancer screening preferences among trans-masculine individuals: patient-collected human papillomavirus vaginal swabs versus provider-administered pap tests. LGBT Health. 2017;4:252–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]