Abstract

Purpose: Transgender (trans) populations experience health inequities. Gender affirmation refers to psychological, social, legal, and medical validation of one's gender and is a key social determinant of trans health. The majority of research has focused on medical affirmation; however, less is known about the role of social and legal affirmation in shaping trans health. This review aimed to (1) examine how social and legal gender affirmation have been defined and operationalized and (2) evaluate the association between these forms of gender affirmation and health outcomes among trans populations in the United States.

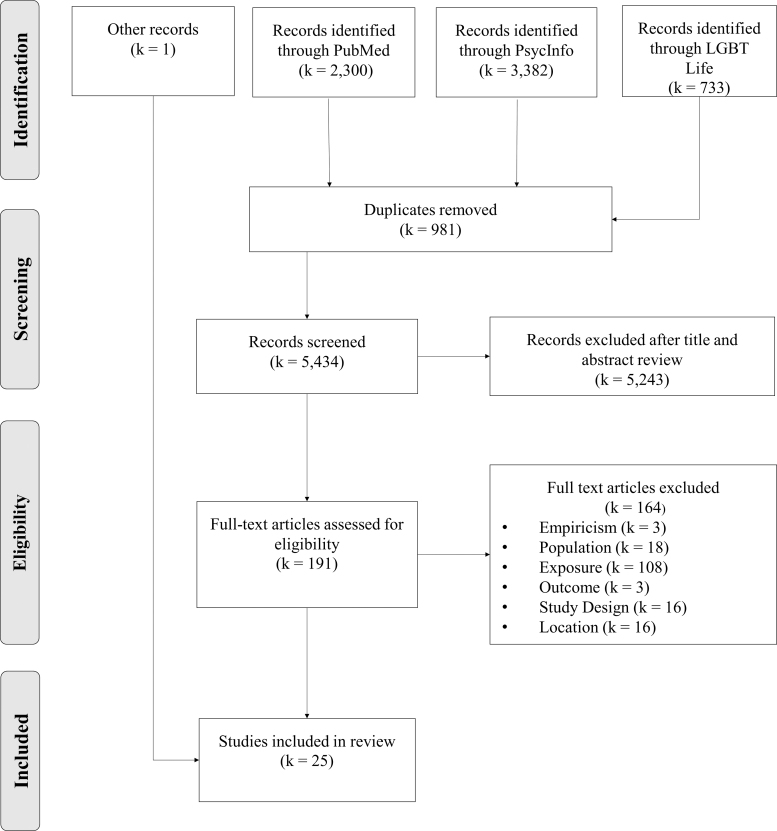

Methods: We conducted a systematic search of LGBT Life, PsycInfo, and PubMed using search strings targeting transgender populations and gender affirmation. This review includes 24 of those articles as well as 1 article retrieved through hand searching. We used a modified version of the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool to evaluate study quality.

Results: All studies relied on cross-sectional data. Studies measured and operationalized social and legal gender affirmation inconsistently, and some measures conflated social gender affirmation with other constructs. Health outcomes related to mental health, HIV, smoking, and health care utilization, and studies reported mixed results regarding both social and legal gender affirmation. The majority of studies had serious methodological limitations.

Conclusion: Despite conceptual and methodological limitations, social and legal gender affirmation were related to several health outcomes. Study findings can be used to develop valid and reliable measures of these constructs to support future multilevel interventions that improve the health of trans communities.

Keywords: social gender affirmation, legal gender affirmation, transgender, nonbinary

Introduction

Transgender (trans) refers to people whose gender identity does not align with the culturally prescribed expectations associated with their assigned sex at birth. In this article, we use this umbrella term to include people who identify within the gender binary (i.e., trans men and trans women) and those who identify outside of it (e.g., nonbinary, gender nonconforming, and agender).1

Despite advances in public awareness and legal protections, trans people continue to face health inequities across a variety of conditions, including chronic diseases, mobility and cognitive disabilities, HIV, mental health conditions, hazardous alcohol use, and substance use disorders.2–5 These inequities have been attributed to inequitable and exclusionary laws and policies, societal discrimination, and lack of access to quality health care, all of which are rooted in anti-trans stigma.5,6 The Gender Minority Stress Theory, which was adapted from the Minority Stress Model, has been widely used to describe associations between different forms of anti-trans stigma (e.g., internalized, anticipated, and enacted) and adverse health outcomes among trans communities.6–13

The Gender Affirmation Framework adds to minority stress theoretical frameworks by articulating the importance of gender affirmation in shaping the health of trans communities.14 According to this model, gender affirmation refers to the iterative process of being recognized and supported in one's gender identity, expression, and/or role. In contrast to transition, which implies a definitive start and end-point, gender affirmation occurs throughout the lives of trans people.15 The Gender Affirmation Framework hypothesizes that in the context of widespread stigma, trans people with unmet gender affirmation needs are more likely to engage in risk behaviors and experience adverse mental and physical health outcomes than those whose gender affirmation needs are fulfilled.14

Reisner et al. identified gender affirmation as a key social determinant of trans health containing four dimensions: social, legal, psychological, and medical. Social gender affirmation, distinct from general social support, occurs when institutions or individuals validate a trans person's identity through, for example, use of correct names and pronouns. Legal gender affirmation refers to amending names and gender markers on documents such as social security cards, birth certificates, and driver's licenses. Psychological gender affirmation is an intrapersonal experience of gender self-actualization and validation. Finally, medical affirmation refers to hormones, surgery, and other procedures that align the function or appearance of a trans person's body with their identity.15

To date, research on the association between gender affirmation and health outcomes among trans populations has primarily focused on medical gender affirmation. A recent systematic review found evidence of association between use of hormone replacement therapy and improved depression, anxiety, and quality-of-life outcomes among trans individuals.16 Subsequent studies on medical and psychological gender affirmation have found that these factors protect against suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), binge drinking, and substance use, and promote self-esteem and quality of life.17–21

Comparatively less attention has been paid to the influence social and legal gender affirmation may have on trans health. Trans people have diverse gender affirmation needs that do not always include medical gender affirmation. While some scholars have conceptualized gender affirmation as the “treatment” or relief for gender dysphoria,15 others recognize that DSM-V-codified, transnormative experiences of gender dysphoria are not applicable across the trans spectrum.22–24 For example, preliminary evidence suggests that nonbinary people may be less likely to want specific forms of medical gender affirmation than binary trans people who share their assigned sex at birth.25

Therefore, understanding the impact social and legal gender affirmation have on health outcomes is uniquely important for the subset of the trans population that does not have medical gender affirmation needs. Moreover, understanding how social and legal forms of gender affirmation influence health is important, given the high financial costs and overall inaccessibility of medical gender affirmation for those who do desire it.1 Aside from cost, barriers to medical gender affirmation include lack of insurance coverage, geographic inaccessibility, anticipated and enacted stigma in health care settings, medical contraindications (i.e., history of thrombosis for estrogen use or coronary artery disease for testosterone use), age, and anticipating others' negative reactions.25,26

Finally, social and legal gender affirmation needs will remain relevant across the lifespan for trans people regardless of whether they have fulfilled any medical gender affirmation needs.15 As such, it stands to reason that these four dimensions of gender affirmation are intimately connected. For example, fulfilling one form of gender affirmation needs (e.g., medical) may facilitate fulfillment of other gender affirmation needs (e.g., social and psychological). However, it is important to note that gender affirmation needs do not arise and are not addressed in a linear manner. Rather, gender affirmation needs are a product of the individual and their social context, and these interconnected gender affirmation dimensions may interact to fuel health inequities among trans populations.

Thus, this scoping review has dual purposes. First, we examine how social and legal gender affirmation have been quantitatively operationalized in health research. Second, we evaluate evidence for associations between social and legal gender affirmation and health outcomes. Findings can potentially inform efforts to understand gender affirmation as a multidimensional set of distinct yet interlinked needs that may act in concert and impact health inequities among trans populations.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Empiricism

Studies were included if they presented results from either primary or secondary data analyses. Commentaries, reviews, rapid communications, and other nonempirical articles were excluded.

Population

The study sample needed to include trans participants. While we did not exclude studies that also included cisgender participants, these studies were only included if they presented disaggregated data on the trans subsample.

Exposure

Studies needed to use a quantitative measure of social or legal gender affirmation. Given the range of terms used to describe gender affirmation, we included studies that measured related constructs (i.e., legal name change and social support related to gender identity) as well.

Outcome

We included studies that measured any mental, physical, or behavioral health outcome; studies that only measured social determinants of health such as employment status, education, or stigma were not included.

Study design

Studies needed to quantitatively examine the association between social or legal gender affirmation and a health outcome. We excluded studies that used exclusively qualitative methods.

Location

Trans identity and the mechanisms through which gender affirmation works are based on socially structured, U.S.-American notions of the gender binary that do not apply cross-culturally.22 Therefore, we only included studies in which all participants were living in the United States to minimize the application of these hegemonic norms to other populations.

Literature search

We carried out an electronic database search of LGBT Life, PsycInfo, and PubMed using a combination of two search strings to maximize efficiency and sensitivity (Table 1). The first search string targeted studies with trans samples with terms and medical subject headings (MeSH) such as “gender minority” and “Transgender Persons [MeSH].” The second search string used terms and medical subject headings related to gender affirmation such as “Social Support [MeSH]” and “affirm.” These search strings were developed in consultation with a health sciences librarian and informed by those used in previous systematic reviews.27 The final search included all articles published in English after January 1, 2002, to avoid retrieving articles published before gender affirmation was conceptualized in health research.28 The search was conducted on October 16, 2019.

Table 1.

PubMed Search Strings

| Concept 1: Transgender |

| “Sex Reassignment Procedures”[Mesh] OR “Gender Identity”[MeSH] OR “Transgender Persons”[MeSH] OR “Transvestism”[Mesh] OR “Transsexualism”[Mesh] OR “Health Services for Transgender Persons”[Mesh] OR “transvestite”[tiab] OR “transvestites”[tiab] OR “2-spirit”[tiab] OR “two spirit”[tiab] OR “2 spirit”[tiab] OR “two-spirit”[tiab] OR transsexual[tiab] OR transsexuals[tiab] OR transsexuality[tiab] OR transexual[tiab] OR transexuals[tiab] OR transexuality[tiab] OR “trans sexual”[tiab] OR transgender[tiab] OR transgenderism[tiab] OR transgenders[tiab] OR transgendered[tiab] OR transgenderists[tiab] OR “Gender Minorities”[tiab] OR “Gender Minority”[tiab] OR “Gender Variant”[tiab] OR Genderqueer[tiab] OR “gender queer”[tiab] OR “Gender variance” [tiab] OR “Trans person”[tiab] OR “Trans people”[tiab] OR Non-binary[tiab] OR Nonbinary[tiab] OR “Gender dysphoria”[tiab] OR “Gender dysphoric”[tiab] OR “Gender incongruent”[tiab] OR “Gender incongruence”[tiab] OR “Gender non-conforming”[tiab] OR “Gender nonconforming”[tiab] OR “Gender nonconformity”[tiab] OR “gender non-conforming”[tiab] OR “Gender non-conformity”[tiab] OR Genderfluid[tiab] OR gender-fluid[tiab] OR “Gender fluid”[tiab] OR “cross dress”[tiab] OR “cross dressed”[tiab] OR “cross dresser”[tiab] OR “cross dressers”[tiab] OR “cross dresses”[tiab] OR “cross dressing”[tiab] OR crossdress[tiab] OR crossdressed[tiab] OR crossdresser[tiab] OR crossdressers[tiab] OR crossdresses[tiab] OR crossdressing[tiab] OR “cross-dress”[tiab] OR “cross-dressed”[tiab] OR “cross-dresser”[tiab] OR “cross-dressers”[tiab] OR “cross-dresses”[tiab] OR “cross-dressing”[tiab] OR “female to male transgender”[tiab] OR “female to male transexual”[tiab] OR transman[tiab] OR “trans man”[tiab] OR transmen[tiab] OR “trans men”[tiab] OR MTF[tiab] OR “trans masculine” [tiab] OR transmasculine[tiab] OR “male to female transgender”[tiab] OR “male to female transexual”[tiab] OR transwoman[tiab] OR transwomen[tiab] OR “trans woman”[tiab] OR “trans women”[tiab] OR FTM[tiab] OR “trans feminine” [tiab] OR transfeminine[tiab] OR Trans-gender[tiab]OR trans-genders[tiab] OR Trans-sex[tiab] OR Trans-sexual[tiab] OR Trans-sexuals[tiab] OR Trans-sexualism[tiab] OR Trans-sexuality[tiab] OR agender[tiab] OR “gender identity disorder”[tiab] OR intersex[tiab] OR “sex reassignment”[tiab] OR “sex change”[tiab] OR “gender reassignment”[tiab] OR “gender change”[tiab] OR “gender confirmation”[tiab] |

| Concept 2: Social and legal gender affirmation |

| “Social Desirability”[Mesh] OR “Attitude of Health Personnel”[Mesh] OR “Respect”[Mesh] OR “Social Support”[Mesh] OR “Name change”[tiab] OR misnaming[tiab] OR “dead names”[tiab] OR “Gender marker”[tiab] OR Pronouns[tiab] OR Respect[tiab] OR respects[tiab] OR respected[tiab] OR affirm[tiab] OR affirming[tiab] OR affirmation[tiab] OR Validation[tiab] OR validates[tiab] |

During the review process, we were not blind to study characteristics, including identities of the study authors or funding sources. The review process began with retrieving all abstracts and removing duplicate citations. The first author then discarded studies that clearly did not meet inclusion criteria based on title and abstract review due to lack of empirical design, exclusive use of qualitative methods, non-U.S. participants, or cisgender samples. Both authors then reviewed the full-text versions of all remaining studies to assess their adherence to eligibility criteria. Interrater reliability was excellent (k=0.911), and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. This study relied solely on de-identified data published in existing literature and as such was exempt from institutional review board review.

Data extraction

We recorded the following characteristics of each included study: study design, sampling methods, gender identification methods, sample characteristics, description of the gender affirmation measure(s) used, health outcomes, the direction and strength of association between social and/or legal gender affirmation and health outcomes, and limitations noted in text relevant to the purpose of the review. In addition, we also recorded any definition of gender affirmation provided in text.

Searches of PubMed, PsycInfo, and LGBT Life retrieved 6415 citations. After removing 981 duplicates, we performed a title and abstract screen of the 5434 remaining citations. We excluded 5243 citations at this stage. After retrieving the full text for the remaining 191 citations, we excluded 167. The most common reasons for exclusion at this stage related to study exposures; 107 studies were excluded for not assessing social or legal gender affirmation. One article was retrieved through hand-searching citations of included records.

To assess study quality, we rated each study using a modified version of the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool (NIH QAT) appropriate to each study's design. All studies in this review were cross-sectional; therefore, we used the tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies and removed items specific to longitudinal studies.29 Given the purpose of this review, we applied the items related to exposure measurement to social and legal gender affirmation rather than to all exposures measured in each study.

Our final tool contained eight criteria related to study conceptualization, participant selection, measurement, and analysis. As per the NIH QAT guidelines, we used the criteria to rate each study as good, fair, or poor based on an overall evaluation of how bias impacted study results.29 This review describes the measures of social and legal gender affirmation, summarizes the findings regarding association with health outcomes, and evaluates the methodology of the 25 included studies (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of search procedures.

Results

The 25 included studies represented 20 unique samples. Ten of the studies (40%) focused on trans youth,30–39 while the remainder enrolled exclusively adult samples.21,28,40–52 Regarding gender identity, 11 studies (44%) included only trans women and girls21,28,33,39,42,44,46,47,49–51 and 1 (4%) included only trans men.48 While many studies enrolled all eligible participants whose gender identity does not align with their assigned sex at birth, 11 studies (44%) explicitly identified the nonbinary proportion of their sample.31–33,36–40,43,48,52 Table 2 details the study design, sample, relevant findings, and measure(s) of social and/or legal gender affirmation used in each study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study | Design | NIH QAT rating | Sampling | Gender identification method | Sample characteristics | Health outcome | Summary of relevant findings | Measure of social/legal gender affirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glynn et al.21 | Cross-sectional | Good | Purposive sampling in community spaces and venues Two rounds; second to “increase size and diversity of the sample” |

Self-identification as transgender or transsexual woman | 573 trans women with a history of sex work from San Francisco, CA 41% Black, 21% white, 19% Asian/Pacific Islander, 19% Latina |

Mental health: Depression Self-esteem Suicidal ideation |

Social, psychological, and medical gender affirmation were significant predictors of lower depression and higher self-esteem. There was no association with suicidal ideation. | Social gender affirmation: Satisfaction with Family Social Support Scale; 5 items rated on 3-point scale; sample: “During the last 30 days, how much more help would you have liked from family members to help you do things?” |

| Nuttbrock et al.28 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Not reported | Not reported | 43 trans women sex workers from New York City metro 33% Hispanic, 49% African American (rest of sample not described) |

Mental health: Depressive symptoms |

There was a high prevalence of gender affirmation from partners, but it was not associated with depressive symptoms. There was a negative association between gender affirmation from friends and gender affirmation from parents with depressive symptoms. | Gender affirmation: Degree to which specific people (family, friends, etc.) “[see] female attire as a natural part of who they are a person.” |

| Fisher et al.30 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Online sampling through Facebook and e-mail lists; national | Not reported | 90 trans men and 60 trans women, 14–21 years old, with cisgender male sexual partners 5.3% African American/black, 6.0% American Indian/Alaska Native, 4.0% Asian, 11.3% Hispanic/Latino, 88.7% non-Hispanic white, 7.3% other |

HIV prevention: Willingness to participate in PrEP research |

Most participants reported that at least one of their caregivers (primary or secondary) was somewhat to very accepting of their trans identity, although this was not associated with willingness to participate in PrEP research. Participants identified access to trans affirming counseling during PrEP research as a factor that would facilitate their involvement. | Assessed family disclosure and acceptance of gender and sexual orientation identities; measure was not described. Listed “being able to talk to research staff who are affirming of my gender identity” on checklist of potential facilitators to PrEP study participation. |

| Goldenberg et al.31 | Cross-sectional | Good | Purposive sampling across 14 U.S. cities through community-based agencies | Gender identity not the same as sex assigned at birth | 110 Black trans and gender nonconforming youth 68.18% transfeminine, 10.00% transmasculine, 21.82% gender diverse |

Health care utilization: Delaying primary care |

Not delaying health care was associated with having gender affirmation needs met in bivariate analysis. In adjusted models, experiencing gender affirmation in health care settings was associated with decreased odds of delaying/not using health care. Gender affirmation in health care modified the relationship between anticipated stigma and probability of delaying or not using primary care. | Gender affirmation occurring in health care: 8 items related to need for and 8 items related to access to gender affirmation in health care; 4-point scale; sample “It is important to me that my preferred name and gender pronouns are always used at the places where I receive health care, including in the waiting room.” |

| Kuper et al.32 | Cross-sectional | Good | Recruitment not described; survey was online; national | Self-identification as a gender identity other than or in addition to their sex assigned at birth | 1896 trans people ages 14–30 89.7% White, 5.5% black or African American, 5.5% American Indian or Alaska Native, 9.2% Hispanic or Latino, 5.4% Asian or Pacific Islander, 1.7% Arab or Middle Eastern 21.9% assigned male at birth, 78.1% assigned female at birth |

Mental health: Suicide attempt Suicidal ideation Suicide risk |

Gender-related support and gender-related expression ability were associated with decreased odds of past-year suicide attempt, past-year suicidal ideation, and current suicide risk, but was not significant in adjusted models. | Gender-related support: 4 items; α=0.82; sample: “People in my life have been accepting of my gender identity/expression.” Gender-related expression ability: 3 items; α=0.79; sample: “I have been able to openly dress and style myself the way that I want.” Each rated on a 4-point scale; measures developed based on qualitative interviews and confirmatory factor analysis |

| Le et al.33 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Purposive sampling: peer referral, social media, community organizations, health clinics | Self-identification as any gender other than that typically associated with an assigned male sex a birth | 301 trans female youth ages 16–24 from San Francisco, CA 44.2% female, 32.9% transgender, 22.9% genderqueer/fluid/questioning 36.5% white, 21.9% Latina, 13.0% African American, 6.3% Asian, 7% other race, 15.3% mixed |

Mental health: Psychological distress |

A greater proportion of participants who reported that their parents were their primary source of social support reported parental acceptance than those who reported a different primary source of social support. | Parental acceptance: 10 dichotomous items; acceptance defined as endorsement of 6+; sample: “Did any of your parents or caregivers ever talk about your trans identity with you?”; α=0.775 |

| Cross sectional | Poor | N/A, used electronic health records | Not reported | 180 electronic health records from trans patients at a clinic serving people ages 12–29 in Boston, MA 63.04% FTM, 36.96% MTF, 23.91% racial/ethnic minority, 76.09% white non-Hispanic |

Smoking | Gender affirmation was not associated with current or lifetime cigarette smoking. | Gender affirmation: number of following items in electronic health record: Family support for transgender identity Legal name change Legal gender identification change Involvement with transgender organizations |

|

| Pariseau et al.35 | Mixed methods | Fair | Recruited from “an interdisciplinary gender clinic serving transgender youth”; procedures not reported | Not reported | 54 patients ages 8–17 at a gender clinic in Boston with at least one caregiver | Mental health Depressive symptoms Anxiety symptoms Internalization and externalization of problems |

Past acceptance from the primary caregiver was associated with decreased odds of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and internalizing problems. Acceptance from siblings was associated with decreased odds of externalizing problems and thoughts of suicide. | Gender acceptance: Applied a coding system to clinical interviews. Coded for parental past and current gender acceptance and sibling current gender acceptance. |

| Pollitt et al.36 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Recruited from three U.S. cities; procedures not described | Two-step method | 129 trans and genderqueer youth ages 15–21 10.1% Asian/Pacific Islander, 24.8% black, 27.1% white, 26.4% Multiracial, 11.6% no race reported 34.1% trans woman, 31.0% trans man, 10.9% different gender—assigned sex male, 24.0% different gender—assigned sex female |

Mental health: Depressive symptoms Negative suicidal ideation Self-esteem Positive suicidal ideation (i.e., wanting to continue to live) |

Among participants who had a chosen name, use of the chosen name at home, school, and work was associated with decreased likelihood of depressive symptoms and negative suicidal ideation and increased odds of higher self-esteem. Use of the chosen name at home was also associated with positive suicidal ideation. | Chosen name use: one item about whether participant had a “preferred name different from the name they were given at birth” & whether they were able to go by this preferred name at home, school, work, and with friends. Family acceptance of gender identity: single item rated on a 4-point scale |

| Reisner et al.37 | Cross-sectional | Good | Purposive sampling of youth engaged in care at an Adolescent Medicine Trials Unit site from 14 U.S. cities | Two-step method cross-classifying sex at birth and current gender identity | 181 transgender youth ages 16–24 from 14 U.S. cities 76.8% transfeminine, 23.2% transmasculine 69.1% people of color |

HIV prevention: Engagement in counseling or programs with HIV prevention content HIV treatment HIV care continuum |

Social gender affirmation in HIV-related medical care predicted involvement in primary prevention for seronegative youth, but was not associated with care continuum for seropositive youth. | Social gender affirmation in health care: single item; “In the past 12 months, how supported have you felt in your gender identity or gender expression at place(s) where you accessed HIV-related services?” |

| Russell et al.38 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Recruited from three U.S. cities; procedures not described | Not reported | 129 trans and genderqueer youth ages 15–21 38% MTF, 38% FTM, 7% MTDG, 17% FTDG 24% white, 8% Asian, 33% black, 28% multiracial, 7% not reported |

Mental health: Depressive symptoms Suicidal ideation Suicidal behavior |

Chosen name use in more contexts predicted fewer depressive symptoms, less suicidal ideation, and less suicidal behavior. | Chosen name use: one item about whether participant had a “preferred name different from the name they were given at birth” and whether they were able to go by this preferred name at home, school, work, and with friends. |

| Wilson et al.39 | Cross-sectional | Good | Peer referral, respondent-driven sampling, and social media outreach | Identifying as any gender other than that associated with their assigned male sex at birth | 216 sexually active trans female youth without HIV from San Francisco 16.7% genderqueer, 31.9% transgender, 44.4% female, 6.9% other 5.6% Asian, 13.4% African American, 23.1% Latina, 15.3% mixed, 34.3% white, 8.3% other |

Mental health: PTSD Mental health symptoms (Brief Symptom Inventory) Depression Stress related to suicidal thoughts |

Youth with higher parental acceptance of their transgender identity reported significantly lower odds of PTSD compared to those with lower parental acceptance. There was no relationship for mental health symptoms, depression, and stress related to suicidal thoughts. | Parental acceptance of transgender identity: “Parental acceptance was measured by developing 10 questions based on research from the Family Acceptance Project.” |

| Barr et al.40 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Purposive sampling through community and university organizations and social media; national Two rounds; second round devoted to people of color |

Two-step method; included all participants who reported a gender identity different than their assigned sex at birth | 571 trans adults 36.6% female, 38.0% male, 25.4% nonbinary 79.5% white, 9.5% multiracial, 3.7% black, 4.2% Latino, 1.6% Asian, 0.8% other |

Mental health: Psychological well-being |

Transgender community belongingness mediates the relationship between strength of transgender identity and psychological well-being. | Transgender community belongingness: 9 items; 5-point scale; some relate to social gender affirmation (“There are places in the trans community where I feel understood and accepted”) and some do not (“There are places within the trans community where I can get support”) |

| Bockting et al.41 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Online sampling; national; quotas to recruit equal numbers of transsexuals, cross-dressers, drag queens and kings, and “other” transgender people | Self-identification as transgender | 1093 trans adults ages 18–65 57.5% trans women, 42.5% trans men 79.4% white, 5.1% Latino, 2.4% African American, 1.6% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1.0% Native American, 7.0% Multiracial, 3.5% other |

Mental health: Mental health symptoms |

Family and peer support were significantly associated with decreased odds of mental health symptoms. Peer support moderated the relationship between enacted stigma and mental health symptoms in such a way that high peer support removed the association between enacted stigma and mental health symptoms. | Family support: “How supportive do you feel your family of origin (parents and/or siblings) is regarding your transgender identity?” and “How supportive do you feel your immediate family (partner, children) is regarding your transgender identity” 7-point scale; α=0.88 Peer support: “What portion of your social time is spent with transgender people?” and “How often have you felt like you were the only transgender person in the area where you live?” 7-point scale; α=0.87 |

| Crosby et al.42 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Community-based outreach in Atlanta, GA, including venue-based sampling and word-of-mouth referrals from transgender advocates | “Having been assigned male at birth and self-identifying as either a transgender woman, female, or other gender non-conforming identity” | 77 Black trans women | Mental health: Mental health outcomes (Brief Symptom Inventory) |

Social, but not medical gender affirmation was associated with a lower likelihood of mental health outcomes. | Social gender affirmation composite: 5 items: 1. Legal name change 2. Legal photo ID with gender marker changed 3. Do not avoid thinking about gender identity 4. in a relationship 5. Reporting finding sex to be blissful |

| Fuller and Riggs43 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Purposive sampling through social media and community organizations; national | Not reported | 345 trans adults 31.6% male, 25.2% nonbinary, 24.6% female, 13.0% another gender, 5.5% agender 75.7% White, 4.3% black, 3.5% Hispanic, 3.2% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 5.5% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7.8% other |

Mental health: Psychological distress |

Gender-related family support was negatively correlated with psychological distress. | Gender-related family support: “How supportive has your family of origin been of your trans and/or gender diverse identity?”; 4-point scale |

| Hill et al.44 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Venue-based sampling through the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund Name Change Project in New York, NY | Identifying as a transgender woman, trans woman, transgender female, or MTF transgender/transsexual person | 65 trans women of color 52.3% Black/African American, 7.7% Pacific Islander, 46.2% Hispanic/Latino |

Health care utilization: Delaying medical care Nonprescribed Hormone Use |

Legal name change was associated with higher monthly income, stable housing, and postponement of care due to gender identity, nonprescribed hormone use, and verbal harassment from family. | Legal name change: single-item dichotomous measure |

| Kidd et al.45 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Online sampling; national | Participants gave open-ended descriptions of gender identity Self-identification as transsexual, cross-dresser, drag queen or king, or other (“My transgender identity doesn't fit any of the above categories”) Participants reported “the degree to which they felt like a woman or a man” and sex assigned at birth |

631 transfeminine and 473 transmasculine adults Sample primarily white |

Smoking | In bivariate analysis, gender marker change was associated with decreased odds of smoking in the past 3 months. This was retained for transfeminine participants in multivariable models, but not for transmasculine. | Legal document gender marker change: Determined by comparing participants' sex assigned at birth and their response to the question “According to your current birth certificate, what is your legal sex?” |

| Nuttbrock et al.46 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Online and community-based sampling | “Medical assignment as ‘male’ at birth with a later conception of one's self as not ‘completely male’ in all situations or roles” | 571 trans women from New York City metro, ages 19–59 43.9% Hispanic, 26.8% non-Hispanic white, 21.6% non-Hispanic black, 7.6% other |

Mental health: Major depression |

Gender affirmation was associated with decreased likelihood of major depression across the life course. | Transgender identity affirmation: Percentage of time “relationship partners acted upon disclosures of transgender identity in a positive or affirming way” and the percentage of time these individuals “treated them the way they wanted to be treated with regard to gender.” Rated on a 6-point scale for each of six different types of relationships: parents, siblings, fellow students, friends, coworkers, and sex partners. |

| Poteat et al.47 | Mixed methods | Fair | Purposive sampling at community-based organizations, health care centers, and social media First round of recruitment occurred in Baltimore; Washington, DC, was added to increase sample size |

Assigned male at birth and identifies as a female/woman or transgender | 201 Black and Latina trans women ages 19–82 from Baltimore or Washington, DC 62.2% Black/African American, 17.4% multiracial, 11.0% other race, 9.5% Indigenous 26.9% Latina/Hispanic |

HIV prevention: PrEP willingness |

Legal gender affirmation was associated with lower odds of PrEP willingness in adjusted models. | Legal gender affirmation: single-item measure of the extent to which identification documents list their desired name and gender marker |

| Reisner et al.48 | Cross-sectional | Poor | Convenience sampling online and in person; Boston, MA | Two-step method based on sex assigned at birth and current gender identity | 171 trans men who have sex with men 81.5% white, 7.5% Hispanic, 2.9% black, 6.9% multiracial, 1.2% other 51.4% binary; 48.6% nonbinary |

HIV prevention: Sexual risk STIs Number of sexual partners Condomless sex |

Syndemics (drinking, poly-drug use, depression, anxiety, CPA/CSA, IPV) were associated with increased odds of all sexual risk outcomes. Syndemics were associated with sexual risk only for participants who had social gender affirmation. Social gender affirmation was associated with increased odds of lifetime STI diagnoses, having 3+ sexual partners, and decreased odds of condomless sex. | Social gender affirmation: single-item dichotomous measure; “Do you live full time in your identified gender?” |

| Rosen et al.49 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Convenience sampling at HIV and transgender-related community events, social and community-based organizations, and word of mouth | Assigned male sex at birth and identified as female, woman, or transgender | 201 Black and Latina trans women with HIV, ages 15+, from Baltimore or Washington, DC 62.2% Black/African American, 17.4% multiracial, 11.0% other race, 9.5% Indigenous 26.9% Latina/Hispanic |

HIV treatment: Treatment interruptions |

Medical, but not legal gender affirmation was associated with HIV treatment interruptions in bivariate and multivariable models. | Legal gender affirmation: single-item measure of the extent to which identification documents list their desired name and gender marker |

| Sevelius et al.50 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Purposive sampling at community and clinic sites across 4 U.S. cities; sites organized own recruitment procedures; examples: community outreach, word of mouth, referrals from service providers | Assigned male at birth and identify as transgender or female | 858 trans women of color 49% Hispanic/Latina, 42% black, 8% other race From San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago |

HIV treatment: Viral suppression |

Gender affirmation and health care empowerment mediated the relationship between transgender-related discrimination and viral suppression such that participants who reported transgender-related discrimination were more likely to be virally suppressed if they also reported higher levels of gender affirmation and health care empowerment. | Gender affirmation: Access to gender affirmation in health care: 12 items rated on a 5-point scale; sample: “During your last HIV medical appointment, how welcoming was your medical care provider's waiting room for trans women?”; α=0.88 Need for gender affirmation: 5 items rated on 5-point scale; sample: “How important is it that strangers call you ‘she’ when talking to you?”; α=0.87 Satisfaction with gender affirmation: 5 items rated on 5-point scale; sample: “How satisfied are you with your current level of femininity?”; α=0.87 |

| Sevelius et al.51 | Cross-sectional | Fair | Purposive sampling by street outreach, venue-based sampling, and snowball sampling in San Francisco, CA | Assigned male sex at birth and identify as female, transgender, or a gender identity other than male | 59 trans women on ART for HIV, living in San Francisco 62.7% Black/African American, 6.8% white/Caucasian, 10.2% Hispanic, 20.3% other |

HIV treatment: Antiretroviral therapy adherence Viral load |

Higher importance of gender affirmation was associated with ART adherence in multiple models, but not with HIV viral load. | Gender affirmation: Importance of gender affirmation: 5 items rated on 5-point scale; sample: “How important is it that strangers call you ‘she’ when talking to you?”; α=0.86 Satisfaction with current gender expression: 5 items rated on 5-point scale; sample: “How satisfied are you with your current level of femininity?”; α=0.91 |

| Stanton et al.52 | Cross-sectional | Good | Purposive sampling at event venues, through snowball and respondent-driven sampling, and online | “All respondents who did not identify as cisgender” | 402 trans and gender nonconforming adults 30% Black, 12% Hispanic/Latino/a, 6% Asian/Pacific Islander, 5% Native American, 23% white, 19% Multiracial, 6% other 21% male, 21% female, 32% MTF transgender, 18% FTM transgender, 35% other |

Mental health: Psychological well-being |

Family support positively predicted well-being, but was not significant when controlling for demographic and health behavior covariates. | Family support: “As a lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender person, how much do you now feel supported by your family?” 6-point scale |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CSA/CPA, childhood sexual abuse/childhood physical abuse; FTDG, female-to-different-gender; FTM, female-to-male; IPV, intimate partner violence; MTDF, male-to-different-gender; MTF, male-to-female; NIH QAT, National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Gender affirmation definitions

Of the 25 included studies, 8 (32%) explicitly defined gender affirmation (Table 3).21,31,32,34,37,42,48,50 Definitions of gender affirmation relied on terms such as recognition, validation, positive reinforcement, and support and centered around gender affirmation's inherently interpersonal yet subjective nature. For example, one article described gender affirmation as, “Perceiving validation of one's gender identity and expression, and it may involve having a body image that is concordant with one's gender identity, along with social recognition and legitimacy, and acceptance of the transgender self” (emphasis added).42 Most definitions did not conflate gender affirmation with transition. However, one study identified social transition (i.e., changing one's name, pronouns, or gender presentation) as “the critical gender affirmation component.”48

Table 3.

Definitions of Gender Affirmation Present in Included Studies

| Study | Definition |

|---|---|

| Crosby et al.42 | “[Gender affirmation] is described as perceiving validation of one's gender identity and expression, and it may involve having a body image that is concordant with one's gender identity, along with social recognition and legitimacy, and acceptance of the transgender-self.” |

| Kuper et al.32 | “The ability to identity and express one's gender and have this sense of self accurately reflected back by others…” |

| Glynn et al.21 | “…gender affirmation is the process by which transgender individuals have interactions with their environment that recognize and value their gender expression.” |

| Goldenberg et al.31 | “… a dynamic social process through which individuals receive support for their gender identity and expression.” |

| Menino et al.34 | “…the interpersonal, interactive process whereby persons receive social recognition and support for their gender identity and expression.” |

| Reisner et al.48 | “Gender affirmation has been defined as an interpersonal and shared process through which a person's identity is socially recognized. Gender affirmation is thus a dynamic process that can include social (e.g., name, pronoun, and gender expression), medical (e.g., cross-sex hormones and surgery) and/or legal (e.g., legal name change and gender marker change) dimensions. Despite multiple dimensions of gender affirmation, this study conceptualizes social transition (with or without medical and/or legal transition) as the critical gender affirmation component shaping sexual health behaviors…” |

| Reisner et al.37 | “Gender affirmation refers to being recognized or affirmed in one's gender identity or expression.” |

| Sevelius et al.51 | “‘Gender affirmation’ is an interpersonal process in which a person receives validation of their gender identity and expression.” |

Gender affirmation measurement

While definitions of gender affirmation were largely consistent, measures of social and legal gender affirmation were not. No two studies used the same assessment of social or legal gender affirmation. Two studies created composite measures of gender affirmation that included both social and legal components. Crosby et al. used five items assessing legal name change, gender marker change, relationship status, avoidance of thinking about gender identity, and “finding sex to be blissful.”42 Menino et al. also created a composite measure that included name and gender marker change along with family support for transgender identity and involvement in transgender organizations.34

Most other measures assessed social gender affirmation from one or multiple particular sources, including family, peers, health care providers, and school staff. One study used a measure of transgender community belongingness that included items related to receiving gender affirmation from trans peers.40 Eight studies developed measures of gender affirmation from family or parents. While these measures were frequently referred to as “family support” or “parental acceptance,” they used items specific to identity affirmation such as “Did any of your parents or caregivers ever talk about your trans identity with you?”33 One study measured “peer support” with items related to time spent with other trans people and feelings of isolation due to one's gender identity.41

Three studies specifically assessed the degree to which participants experienced gender affirmation in health care settings. Reisner and colleagues used a single item [“In the past 12 months, how supported have you felt in your gender identity or gender expression at place(s) where you accessed HIV-related services?”], while the other two studies used multi-item measures.31,37,50 Notably, Goldenberg et al. conducted the only included study to asses both need for and access to specific forms of social gender affirmation in health care settings.31

Four studies measured social gender affirmation more generally. Reisner et al. used a single-item measure regarding whether participants live or consistently present as their “identified gender,” while the others developed multi-item measures.48 Two studies used a measure of gender affirmation that contained two subscales: importance of gender affirmation and satisfaction with current gender identity.50,51 Kuper et al. assessed both gender-related support and gender-related expression ability as components of gender affirmation.32

Finally, four studies measured legal aspects of gender affirmation separately from social dimensions. Three of these used single-item measures to assess name change, gender marker change, or both.44,47,49 In the remaining study, participants were considered to have legally changed their gender marker if their reported sex assigned at birth did not match their reported “legal sex” on their birth certificate.45

Evidence for associations with health outcomes

Studies focused on a range of health domains, including mental health (k=14, 56%), HIV (k=7, 28%), health care utilization (k=2, 8%), and smoking (k=2, 8%).

Mental health

Mental health included psychological well-being, self-esteem, psychological distress, depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, PTSD symptoms, and suicidal ideation and attempts. Overall, findings were mixed. However, 13 studies reported at least one significant association between social and legal gender affirmation and mental health outcomes.

Among diverse samples, six of the seven studies that measured an outcome related to depression found a negative association with social gender affirmation.21,28,35,38,39,46 The study that did not find an association operationalized gender affirmation as parental acceptance of transgender identity, which was not associated with depressive symptoms among trans female youth from San Francisco. However, in three other studies of trans youth, acceptance from a primary caregiver and chosen name use across settings (i.e., home, school, and work) were associated with decreased likelihood of depressive symptoms.35,36,38 Social gender affirmation was consistently negatively associated with depression for adult trans women.21,28,46 No studies examined depression and social or legal gender affirmation among other trans adults. We considered suicide a mental health outcome. Of these, the only study focused on trans adults found no association between social gender affirmation and suicidal ideation among trans women with a history of sex work.21 Two studies using the same data collected from trans youth found that chosen name use was associated with decreased odds of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.36,38 However, in two other studies of trans youth, measures of social gender affirmation were not associated with suicide attempt, ideation, or risk, nor with stress related to suicidal thoughts.32,39

Two studies of adult participants found that social gender affirmation was associated with a decreased number of mental health symptoms.41,42 However, there was no association between social gender affirmation and mental health symptoms in a sample of trans female youth.39 Additional adverse mental health outcomes measured included anxiety symptoms, PTSD, internalization and externalization of problems, and psychological distress. Each was negatively associated with social gender affirmation operationalized as various forms of family acceptance.35,39,43

HIV prevention and care

In total, four studies focused on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), one focused on sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), one focused on engagement in HIV prevention (i.e., testing and participation in HIV prevention programs), and four focused on HIV cascade of care outcomes.

Results regarding associations between social and legal gender affirmation and HIV prevention were mixed. In a study of transfeminine and transmasculine youth, reporting engagement with gender-affirming HIV-related medical care positively predicted participation in HIV prevention programs.37 There was no association between caregiver acceptance and willingness to participate in PrEP research in another study of trans youth.30 Among black and Latina trans women, legal gender affirmation was association with lower odds of willingness to take PrEP.47 Finally, a study of trans men who have sex with men found that an indicator of syndemics (alcohol use, poly-drug use, depression, anxiety, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and intimate partner violence) was associated with increased likelihood of lifetime STI diagnoses and currently having three or more sexual partners, but decreased likelihood of condomless sex for participants who reported social gender affirmation.48

All included studies examining HIV cascade of care outcomes were composed of samples that were predominantly or exclusively trans women of color living in urban areas (Table 2). In one study, there was no reported relationship between legal gender affirmation and antiretroviral therapy (ART) treatment interruptions.49 However, Sevelius et al. found that higher importance of social gender affirmation predicted higher ART adherence.51 Finally, among a large, geographically diverse sample of trans women of color, gender affirmation buffered the negative association between experiences of transgender-related discrimination and viral suppression.50

Health care utilization

The two studies examining health care utilization reported significant associations with social or legal gender affirmation. In a study of trans women of color, legal name change was associated with increased odds of postponing medical care and increased odds of nonprescribed hormone use.44 Among black trans youth, experiencing social gender affirmation in health care settings was associated with decreased odds of health care nonuse or delay and modified the relationship between anticipated stigma and health care delay.31,39

Smoking

There were mixed results in the two studies focused on smoking. In an electronic health record study of trans youth, there was no association between indicators of social gender affirmation and smoking34; however, a study of trans adults found that gender marker change was associated with decreased odds of smoking for transfeminine, but not transmasculine participants.45

Strength of evidence

On our modified NIH QAT, 9 studies (36%) received an evaluation of poor, 10 (40%) received an evaluation of fair, and 6 (24%) received an evaluation of good. Table 4 displays the criteria and overall rating for each included study. There were few clear patterns between outcome and quality, limiting our ability to generalize the strength of evidence for an association between social and legal gender affirmation and particular health outcomes. It is noteworthy that five of the six studies that were evaluated as good reported mixed or null findings. These studies found no association between social gender affirmation and psychological well-being, general mental health symptoms, HIV care continuum outcomes, or suicide-related outcomes.21,32,37,39,52 However, social gender affirmation was associated with decreased likelihood of delaying health care, depression, and PTSD and increased likelihood of high self-esteem and use of HIV prevention methods in these studies.21,31,37,39

Table 4.

Modified National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool Criteria Present in Included Studies

| Study | Clear research question | Defined study population | Uniform selection and recruitment | Sample size justification | Sensitive measure of gender affirmation | Clear measure of social/legal gender affirmation with face validity | Clear, reliable, and valid outcome measure | Adequate control for confounding | Overall rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glynn et al.21 | • | • | ○ | ○ | • | • | • | • | Good |

| Nuttbrock et al.28 | • | • | · | ○ | • | ○ | • | ○ | Poor |

| Fisher et al.30 | • | • | • | ○ | ○ | · | ○ | · | Poor |

| Goldenberg et al.31 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | • | • | Good |

| Kuper et al.32 | • | • | · | ○ | • | • | • | • | Good |

| Le et al.33 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | • | ○ | Poor |

| Menino et al.34 | • | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Poor |

| Pariseau et al.35 | • | • | · | ○ | • | ○ | • | ○ | Fair |

| Pollitt et al.36 | • | • | · | ○ | ○ | • | • | • | Fair |

| Reisner et al.37 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | • | • | Good |

| Russell et al.38 | • | ○ | · | ○ | ○ | • | • | • | Fair |

| Wilson et al.39 | • | • | • | • | • | • | ○ | • | Good |

| Barr et al.40 | • | • | ○ | ○ | • | ○a | ○ | • | Fair |

| Bockting et al.41 | • | • | • | ○ | • | ○a | • | • | Fair |

| Crosby et al.42 | • | • | • | ○ | • | ○ | • | ○ | Poor |

| Fuller and Riggs43 | • | • | • | • | • | ○a | • | · | Poor |

| Hill et al.44 | • | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○b | ○ | Poor |

| Kidd et al.45 | • | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | • | • | Poor |

| Nuttbrock et al.46 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | ○ | • | Fair |

| Poteat et al.47 | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | • | • | ○ | Fair |

| Reisner et al.48 | • | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | Poor |

| Rosen et al.49 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | · | ○ | Fair |

| Sevelius et al.50 | • | • | ○ | ○ | • | • | ○ | ○ | Fair |

| Sevelius et al.51 | • | • | • | ○ | • | ○ | • | • | Fair |

| Stanton et al.52 | • | • | • | ○ | • | • | • | • | Good |

•, present/reported; ○, absent; ·, indeterminate.

Measure assessed a construct besides gender affirmation.

Multiple outcomes; some of which were clear, reliable, and valid.

Discussion

Although the studies included in this review differed with regard to outcome and the majority had methodological limitations, the findings suggest that social and legal affirmation play a role in the health of trans communities. While results were mixed, 21 studies (84%) in total found significant associations between social or legal affirmation and mental health outcomes, HIV prevention and care outcomes, health care utilization, and smoking. The small number of studies reviewed and the inconsistent measurement of social gender affirmation precludes us from inferring generalizability on the true importance of both legal and social gender affirmation. Nonetheless, our findings highlight the ways in which these dimensions of gender affirmation may shape the health of trans communities.

Operationalization of social affirmation

Although studies consistently defined social gender affirmation, there was considerable variability in the measurement and operationalization. Some measurements conflated social gender affirmation with social support. For example, one study measured social gender affirmation with the Satisfaction with Family Support Scale, which assesses general instrumental support (e.g., help with daily tasks) rather than support of a participant's transgender identity.21 This study measured mental health outcomes, including depression, self-esteem, and suicidal ideation among adult trans women. Due to the lack of specificity in this measure, comparing findings with similar studies that measured social gender affirmation with items such as “How supportive do you feel your family of origin is regarding your transgender identity?” presents a significant challenge to understanding the role of social gender affirmation in mental health.41,46,52 Although these constructs may have some conceptual overlap, they are distinct.

Other measures conflated social gender affirmation with social transition. Social transition refers to individual-level behaviors that align a person's outward appearance with their identity and shape their interactions with others. These behaviors may include changing dress or hairstyle, disclosing trans identity, or requesting use of a chosen name or new pronouns.53 While transition may function to obtain social gender affirmation, it does not cause it. Therefore, measures such as, “Do you live full time in your identified gender?” are not valid representations of gender affirmation as they do not capture the extent to which people and institutions that respondents interact with recognize, respect, or support a participant's gender identity.48

Furthermore, studies created composite measures that included indicators of both social and legal gender affirmation. Such measures assume that social and legal gender affirmation have comparable impacts on health outcomes. None of the studies assessing legal gender affirmation accounted for the fact that requirements to change gender markers on government documents vary considerably by state.54 Knowing whether participants lacked access to legal gender affirmation on a structural rather than individual level is important when interpreting study findings and highlighting implications for intervention.

Finally, most measures did not consider whether participants desired certain dimension of gender affirmation. The Gender Affirmation Framework describes how adverse health outcomes arise not from identifying as transgender, but from failing to have one's gender affirmation needs met.14 However, only one study included in this review assessed gender affirmation need alongside receipt and analyzed the impact of discrepancies on health care utilization.31 Measures that do not assess gender affirmation using this two-step approach assume all participants in a study have the same gender affirmation needs and reinforce normative ideas regarding what constitutes a “legitimate” trans person.22

Health outcomes

There were mixed findings regarding associations between social and legal gender affirmation and health outcomes. Although measurement differences may explain these findings, social and legal gender affirmation might also increase the degree to which a trans person is perceived to be trans, conferring risk of stigma and contributing to adverse health outcomes in some circumstances. A rich body of qualitative literature describes how people who are visibly gender nonconforming, regardless of trans identity, anticipate, experience, and cope with enacted stigma in public settings; notably, interactions with health care systems are particularly likely to cause stigma-induced stress.13,55,56

While social and legal gender affirmation are not physically apparent in the same way as medical gender affirmation, people whose social and legal gender affirmation needs are met may be motivated to avoid stigmatizing encounters and therefore experience adverse health outcomes. Thus, future research is warranted to examine whether anticipated stigma may mediate the association between these forms of gender affirmation and health care avoidance, nonprescribed hormone use, mental health, and HIV prevention and cascade of care outcomes.

Study quality

Overall, study design and quality diminished the strength of evidence for associations between social and legal gender affirmation and health outcomes. All of the included studies conducted cross-sectional quantitative analyses, thereby preventing any conclusion regarding causality. The lack of valid, reliable, and standardized measures of social and legal gender affirmation hinders our ability to draw definitive conclusions about their relationship with most health outcomes. Furthermore, all studies relied on nonprobability samples. Many recruited online or in clinic settings, limiting the generalizability of their findings. For example, studies using electronic health records from gender clinics are only generalizable to trans people who have access to and choose to seek medical gender affirmation.

Limitations

This review has noteworthy limitations. We employed a systematic approach to searching and screening relevant publications in four databases for this review, but our results are limited by the sensitivity of our search strings and databases. Our search string related to transgender identity was refined based on those used in previously published systematic reviews; however, as gender affirmation is a relatively new and inconsistently measured concept, the search string we created may have contributed to the erroneous exclusion of relevant articles. Finally, the modifications made to the NIH-QAT to apply its criteria more directly to our research question were not validated and may have increased the subjectivity of quality reviews.

Implications

Despite limitations, this systematic review highlights the potential role social and legal gender affirmation may have on the health of trans communities. The Gender Affirmation Framework suggests that fulfillment of social and legal gender affirmation needs reduces trans people's engagement in health risk behaviors.14 Therefore, our findings suggest that interventions seeking to address health inequities among trans communities may benefit from more fully considering social and legal gender affirmation as key social determinants of health.

Additional studies are needed to better understand how social and legal gender affirmation may influence particular health outcomes to guide impactful multilevel interventions. Developing reliable, validated measures that capture both gender affirmation need and receipt should be the first step toward this goal. These measures must be designed to reflect the experience of diverse trans populations as our results suggest that social and legal gender affirmation likely operate differently depending on age and gender identity (i.e., binary vs. nonbinary and transmasculine vs. transfeminine).

It is also particularly important to prioritize engagement, recruitment, and retention of trans people of color and trans migrants in measurement development and validation research as these populations experience compounded health inequities.1,4,6,27,57–59 Finally, studies that investigate the effects of interactions between social, legal, psychological, and medical gender affirmation on health outcomes are needed to determine under what circumstances fulfilling gender affirmation needs can mitigate the impacts of anti-trans stigma and reduce health inequities among trans populations.

Conclusion

Gender affirmation is an important social determinant of trans health. Although accumulating evidence has focused on the importance of medical gender affirmation, social and legal gender affirmation are also critical to promoting the health and well-being of trans populations. The findings from this review establish a need to develop reliable, valid measures of these constructs to more comprehensively understand how gender affirmation influences health outcomes. Interventions designed to increase access to social and legal gender affirmation have the potential to reduce health inequities impacting trans populations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kate Saylor for her assistance in developing the search strings and protocol for this review and Dr. Alison Miller and Gabriel Johnson for providing feedback on early drafts of this article.

Abbreviations Used

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- CSA/CPA

childhood sexual abuse/childhood physical abuse

- DSM-V

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition

- FTDG

female-to-different-gender

- FTM

female-to-male

- MeSH

medical subject headings

- MTF

male-to-female

- NIH QAT

National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool

- PrEP

pre-exposure prophylaxis

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- STIs

sexually transmitted infections

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Cite this article as: King WM, Gamarel KE (2021) A scoping review examining social and legal gender affirmation and health among transgender populations, Transgender Health 6:1, 5–22, DOI: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0025.

References

- 1. James S, Herman J, Rankin S, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilbert PA, Pass LE, Keuroghlian AS, et al. Alcohol research with transgender populations: a systematic review and recommendations to strengthen future studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:138–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of transgender adults in the U.S., 2014–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, et al. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:e1–e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Valentine SE, Shipherd J. A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:24–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. White Hughto JM, Reisner S, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43:460–467 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:38–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbina, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388:412–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Velez BL, et al. Resilience and collective action: exploring buffers against minority stress for transgender individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diver. 2015;2:253–265 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tebbe EA, Moradi B. Suicide risk in trans populations: an application of minority stress theory. J Couns Psychol. 2016;63:520–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rood B, Reisner S, Surace FI, et al. Expecting rejection: understanding the minority stress experiences of transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sevelius JM. Gender affirmation: a framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles. 2013;68:675–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and Gender-Affirming Transgender Clinical Care and Research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S235–S242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughto JMW, Reisner S. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1:21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owen-Smith AA, Gerth J, Sineath RC, et al. Association between gender confirmation treatments and perceived gender congruence, body image satisfaction, and mental health in a cohort of transgender individuals. J Sex Med. 2018;15:591–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai X, Hughto JMW, Reisner SL, et al. Benefit of gender-affirming medical treatment for transgender elders: later-life alignment of mind and body. LGBT Health. 2019;6:34–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomita KK, Testa RJ, Balsam KF. Gender-affirming medical interventions and mental health in transgender adults. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diver. 2019;6:182–193 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Simpson TL, et al. Hormone therapy, gender affirmation surgery, and their association with recent suicidal ideation and depression symptoms in transgender veterans. Psychol Med. 2018;48:2329–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Glynn TR, Gamarel KE, Kahler CW, et al. The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2016;3:336–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vipond E. Resisting Transnormativity: challenging the medicalization and regulation of trans bodies. Theory Action. 2015;8:21–44 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ashley F. Gatekeeping hormone replacement therapy for transgender patients is dehumanising. J Med Ethics. 2019;45:480–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulz SL. The informed consent model of transgender care: an alternative to the diagnosis of gender dysphoria. J Humanist Psychol. 2018;58:72–92 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, et al. Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Social Policy. 2018;15:48–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people. World Prof Assoc Transgend Health. 2012;13:97–104 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poteat T, Scheim AI, Xavier J, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection and related syndemics affecting transgender people. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72:S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nuttbrock L, Rosenblum A, Blumenstein R. Transgender identity affirmation and mental health. Int J Transgend. 2002;4:1–11 [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute of Health. Study Quality Assessment Tools. 2014. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools Accessed December6, 2020

- 30. Fisher CB, Fried AL, Desmond M, et al. Facilitators and barriers to participation in prep HIV prevention trials involving transgender male and female adolescents and emerging adults. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29:205–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldenberg T, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Popoff E, et al. Stigma, gender affirmation, and primary healthcare use among black transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65:483–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuper LE, Adams N, Mustanski BS. Exploring cross-sectional predictors of suicide ideation, attempt, and risk in a large online sample of transgender and gender nonconforming youth and young adults. LGBT Health. 2018;5:391–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le V, Arayasirikul S, Chen YH, et al. Types of social support and parental acceptance among transfemale youth and their impact on mental health, sexual debut, history of sex work and condomless anal intercourse. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(Suppl 2):20781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Menino DD, Katz-Wise SL, Vetters R, Reisner SL. Associations between the length of time from transgender identity recognition to hormone initiation and smoking among transgender youth and young adults. Transgend Health. 2018;3:82–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pariseau EM, Chevalier L, Long KA, et al. The relationship between family acceptance-rejection and transgender youth psychosocial functioning. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2019;7:267–277 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pollitt AM, Ioverno S, Russel ST, et al. Predictors and mental health benefits of chosen name use among transgender youth. Youth Soc. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1177/0044118X19855898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reisner SL, Jadwin-Cakmak L, White Hughto JM, et al. Characterizing the HIV prevention and care continua in a sample of transgender youth in the U.S. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:3312–3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:503–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson EC, Chen YH, Arayasirikul S, et al. The impact of discrimination on the mental health of trans*female youth and the protective effect of parental support. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2203–2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barr SM, Budge SL, Adelson JL. Transgender community belongingness as a mediator between strength of transgender identity and well-being. J Couns Psychol. 2016;63:87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, et al. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:943–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crosby RA, Salazar LF, Hill BJ. Gender affirmation and resiliency among black transgender women with and without HIV infection. Transgend Health. 2016;1:86–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fuller KA, Riggs DW. Family support and discrimination and their relationship to psychological distress and resilience amongst transgender people. Int J Transgend. 2018;19:379–388 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hill BJ, Crosby R, Bouris A, et al. Exploring transgender legal name change as a potential structural intervention for mitigating social determinants of health among transgender women of color. Sex Res Social Policy. 2018;15:25–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kidd JD, Dolezal C, Bockting WO. The relationship between tobacco use and legal document gender-marker change, hormone use, and gender-affirming surgery in a United States sample of trans-feminine and trans-masculine individuals: implications for cardiovascular health. LGBT Health. 2018;5:401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A, et al. Gender identity conflict/affirmation and major depression across the life course of transgender women. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:91–103 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Poteat T, Wirtz A, Malik M, et al. A gap between willingness and uptake: findings from mixed methods research on HIV prevention among Black and Latina transgender women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82:131–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reisner SL, White Hughto JM, Pardee D, Sevelius J. Syndemics and gender affirmation: HIV sexual risk in female-to-male trans masculine adults reporting sexual contact with cisgender males. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27:955–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rosen JG, Malik M, Cooney EE, et al. Antiretroviral treatment interruptions among black and latina transgender women living with HIV: characterizing co-occurring, multilevel factors using the gender affirmation framework. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:2588–2599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sevelius J, Chakravarty D, Neilands TB, et al. Evidence for the model of gender affirmation: the role of gender affirmation and healthcare empowerment in viral suppression among transgender women of color living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2019. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1007/s10461-019-02544-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sevelius JM, Saberi P, Johnson MO. Correlates of antiretroviral adherence and viral load among transgender women living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2014;26:976–982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stanton MC, Ali S, Chaudhuri S. Individual, social and community-level predictors of wellbeing in a US sample of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19:32–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reynolds HM, Goldstein ZG. Social Transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource for the Transgender Community. (Erickson-Schroth L, ed). New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 124–154 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Elias NM. Transgender and Nonbinary Gender Policy in the Public Sector. New York: Oxford Research Encyclopedia Politics, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lubitow A, Carathers J, Kelly M, Abelson M. Transmobilities: mobility, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming public transit riders in Portland, Oregon. Gender Place Cult. 2017;24:1398–1418 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Paine EA. Embodied disruption: “Sorting out” gender and nonconformity in the doctor's office. Soc Sci Med. 2018;211:352–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Operario D, Nemoto T. On being transnational and transgender: human rights and public health considerations. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1537–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheney MK, Gowin MJ, Taylor EL, et al. Living outside the gender box in Mexico: testimony of transgender Mexican Asylum seekers. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1646–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cerezo A, Morales A, Quintero D, Rothman S. Trans migrations: exploring life at the intersection of transgender identity and immigration. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Diver. 2014;1:170–180 [Google Scholar]