ABSTRACT

Background: The objective of this study was to develop a conceptual framework to define a domain map describing the experience of patients with severe mental illnesses (SMIs) on the quality of mental health care.

Methods: This study used an exploratory qualitative approach to examine the subjective experience of adult patients (18–65 years old) with SMIs, including schizophrenia (SZ), bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). Participants were selected using a purposeful sampling method. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 37 psychiatric inpatients and outpatients recruited from the largest public hospital in southeastern France. Transcripts were subjected to an inductive analysis by using two complementary approaches (thematic analysis and computerized text analysis) to identify themes and subthemes.

Results: Our analysis generated a conceptual model composed of 7 main themes, ranked from most important to least important as follows: interpersonal relationships, care environment, drug therapy, access and care coordination, respect and dignity, information and psychological care. The interpersonal relationships theme was divided into 3 subthemes: patient-staff relationships, relations with other patients and involvement of family and friends. All themes were spontaneously raised by respondents.

Conclusion: This work provides a conceptual framework that will inform the subsequent development of a patient-reported experience measure to monitor and improve the performance of the mental health care system in France. The findings showed that patients with SMIs place an emphasis on the interpersonal component, which is one of the important predictors of therapeutic alliance.

Trial registration: NCT02491866

KEYWORDS: Patient-reported experience measures, patient experience, health services research, quality of care, psychiatry, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, severe mental illness, qualitative research

Introduction

Severe mental illnesses (SMIs), including schizophrenia (SZ), bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD), affect approximately one in five persons [1] and are a major cause of long-term disability worldwide [2]. SMIs lead to significant impairments in the general functioning and well-being of an individual [3] and are associated with a higher use of health care resources [3,4], excess costs [3–6] and significant premature mortality [7,8]. Individuals with SMIs face greater difficulties in accessing and receiving health services and are less likely to receive standard level care [9,10]. Indeed, although appropriate treatment modalities exist to address these disorders, there remains a mismatch between need, access and provision of mental health care; in high-income countries, approximately 36 to 50% of people with SMIs have not received any treatment in the past 12 months [11]. Territorial disparities in the provision and organization of psychiatric care also contribute to increasing health inequalities [12]. These SMIs are often unrecognized or misdiagnosed, leading first to a prolonged duration of untreated psychosis and depression [13–16]; an increased risk of relapse and hospitalizations [17–19] and a worsening of symptoms and poor quality of life [20,21]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to better reallocate resources and reorganize the delivery of psychiatric care. For this purpose, it is necessary to measure the quality and performance of mental health care [22–25] to propose strategies to improve its quality and efficiency [26]. There is substantial evidence suggesting that SZ, BD and MDD share common psychopathological manifestations and disabilities [27,28], which can make it problematic and time-consuming to make a correct diagnosis. These arguments argue in favor of studying these three conditions within the continuum of severe mental illnesses rather than as separate disorders. Improving the quality of care requires action at several levels, and the patient experience is now considered an important measure of health care quality [29–31]. Several definitions of the patient experience have been developed, the most frequently cited of which are those of the Beryl Institute [32] and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [33]. Ultimately, these definitions focus on how the range of interactions between patients and care providers influence the patient experience within the health care system. Patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) are used to determine the extent to which care is patient-centered [34]. A positive patient experience has been shown to be an important determinant of treatment adherence, continuity of care and health outcomes [34,35]. There is, however, a lack of consensus on what constitutes high-quality mental health care, which has led to the development of a multitude of instruments that reflect real patient concerns to varying degrees [36]. Some dimensions of the patient experience are common concerns for all patients (eg, information and respect for patient preferences [37,38], however, psychiatric patients have more specific needs that need to be addressed (eg, drug treatment and psychological care). In this context, the Patient-Reported Experience Measure for Improving qUality of care in Mental health (PREMIUM) Group intends to develop a set of PREMs to assess the quality of mental health care for adult patients with SMIs based on modern testing methods, including item banks and computerized adaptive testing (CAT) [39].

The objective of this qualitative study was to develop a conceptual framework to define a domain map describing the experience of patients with SZ, BD and MDD on the quality of mental health care, based on face-to-face semistructured interviews.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study used an exploratory qualitative approach to investigate patients’ experiences with severe mental illness regarding the quality of their mental health care. This type of analysis is based on an exclusively inductive approach which allows to generate new knowledge about a particular phenomenon in the absence of a pre-existing theoretical framework to drive the coding (as opposed to deductive approach) [40].

Participants and setting

The participants in this study were adult psychiatric inpatients and outpatients recruited from a public hospital of the University Hospital (UH) Centre of Marseille and its surroundings (La Conception Hospital, Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Marseille, France). It is the 3rd largest UH in France based on its size and activity. In France, the management of psychiatric disorders in the public sector is organized between intra- (full- and part-time hospitalizations) and extra-hospital structures (medical-psychological centers CMP, day hospital, part-time therapeutic reception centers CATTP, etc.). Each of these extra-hospital structures is administratively associated to a hospital. Eligible patients for this study were (a) adult volunteers (aged over 18 and under 65 years) (b) with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder (according to DSM-V) [41], regardless of current or previous therapies, the duration of illness or the severity of the illness, who were (c) able to read and speak in French and had no comprehension disorders. Vulnerable persons (pregnant women, adults subject to a legal protection measure, etc.), subjects with decompensated organic disease or mental retardation, and patients who were not sufficiently stabilized to participate in an interview were excluded. Individuals aged 65 years and over were also excluded from this study because they have specific issues that differ from those of working-age adults.

Procedure

Participants were selected using a purposeful sampling method based on their characteristics and their relevance to the study objective [42]. Health care teams referred stabilized participants who met the inclusion criteria and who were likely to provide a variety of perspectives. These patients were then approached face-to-face by the interviewer, and all received oral and written information about the purpose and procedure of the study. They were informed that they could interrupt the interview at any time, without prejudice, and that they could contact the study investigator if they had any further questions or needed clarification. In the event of withdrawal from the study, participants were also informed that they could request that their data be deleted. Interested patients were invited to an interview in a private room and were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. The interviewer was an experienced psychologist who was not involved in the patient’s care. All patients interviewed gave their written informed consent before starting the interview and were not compensated for their participation. To cover all the variability regarding the research question, the minimum number of subjects to be included was calculated by taking into account three potential confounding factors: gender, age (≤ 45 years and > 45 years) and location of care (outpatient care, full-time hospitalization and part-time hospitalization). Twelve classes were identified, and a range of 3 to 4 interviews per class was expected (36 to 48 interviews). Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached [43], ie, when newly collected data did not bring new ideas that were necessary for a better understanding of the research question. Table 1 presents the confounding factors that were likely to influence the level of quality of care perceived by individuals. Each interview lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes and took place during the first half of April 2016.

Table 1.

Confounding factors for sample size calculation

| Full-time hospitalization |

Part-time hospitalization |

Outpatient care |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤45yo |

Age >45yo |

Age ≤45yo |

Age >45yo |

Age ≤45yo |

Age >45yo |

|||||||

| Confounding factors | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F |

|

Number of subjects to be included |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

3–4 |

|

Minimum/Maximum: 36–48 interviews | ||||||||||||

| Number of subjects included | 3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

| Total: 37 interviews | ||||||||||||

Note: *yo: years old.

Interview protocol

Data were collected through semistructured interviews [44], which provide valuable information about respondents’ experiences. To do this, an interview guide was developed, including a series of open-ended questions to assess patients’ opinions about the quality of their mental health care (see Table 2). These questions were ordered into a logical sequence, from broad to specific, to generate spontaneous reports from respondents. Clarification or follow-up questions (eg, ‘Can you tell me more about that?’) were asked to clarify participants’ responses if necessary. Participants also provided sociodemographic data (eg, gender, age, educational level, marital status and employment status). Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed, and field notes were taken to further describe the observations made by the respondents.

Table 2.

Interview guide

|

|

|

|

Data analysis

All interviews were subjected to two complementary qualitative analysis methods. In doing so, an inductive approach was chosen to move away from any existing theoretical conception and to develop a conceptual framework drawn from the raw data to reflect all the complexity and dynamics of the respondents’ experience [45]. For publication purposes, patient quotes were translated into English after data analysis. First, data were subjected to the six-stage thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke [46], assisted by the NVivo 11 software (NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) [47]: 1/familiarizing yourself with the data; 2/generating initial codes; 3/searching for themes; 4/reviewing themes; 5/defining and naming extracted themes; and, finally, 6/producing the report. The unit of analysis was a word, sentence or utterance from the verbatim transcripts. Responses were divided into units of meaning and coalesced into overarching themes. Second, data were analyzed with a computerized text analysis method using Alceste software (Analysis of co-occurring lexemes in a set of text segments, IMAGE, Version 2015, Toulouse, France) [48,49]. Based on a statistical distributional analysis of vocabulary, the algorithm creates characteristic classes of words that reflect the common narrative structures in the respondents’ discourse. To do this, Alceste follows a multistep analysis plan. First, the software lemmatizes the text corpus and creates a dictionary of vocabulary, reduced forms and their frequency. The corpus is then automatically divided into elementary context units (ECUs), which correspond to text segments of homogeneous size. Alceste compares these ECUs according to the distribution of their vocabulary and groups those that share a meaning relationship. These word classes are subjected to descending hierarchical classifications to reveal the underlying lexical worlds using the relationship between words, their frequency of occurrence and their associations in the classes. For each lexical class, lexemes are classified according to their representative position using a χ2 test. The higher the χ2 value is, the more significant a lexeme is for the statistical structure of the class. The algorithm aims to establish vocabulary classes that minimize the variability of intraclass statements while maximizing the dissimilarity of interclass statements. Additional analyses, such as correspondence factor analysis and hierarchical ascending classifications, facilitate the representation of links within stabilized word classes. These results were then compared with those obtained during the thematic analysis to refine the themes and capture thematic content that would not have been initially identified. This revised model was then discussed in meetings with a panel of researchers with experience in qualitative research and mental health.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the relevant ethics committee (CPP-Sud Méditerranée V, November 12th, 2014, n°2014-A01152-45). All participants provided written informed consent. This work is supported by an institutional grant from the French national programme on the performance of the healthcare system (PREPS, financed by Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins, 14, avenue Duquesne, 75,350 Paris, France) n°13–0091 QDSPsyCAT. The trial registration is NCT02491866.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 37 patients were interviewed. Just over half of the total sample was male (57%), most respondents were single (68%), had an educational level higher than the bachelor’s degree (62%) and were unemployed (78%). The mean age was 44.1 years old (SD ±11.3). Seven patients reported comorbid addictions (19%). The distribution was balanced between diagnoses of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (35% each), while 11 participants were diagnosed with depression (30%). The average duration of illness was 12.2 years (SD ±9.3). Almost two-thirds of the patients were hospitalized at the time of the interview (65%), 17% of whom were hospitalized under constraint. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 37)

| Total N(%) |

Population ages 15–29 N(%) |

Population ages 30–44 N(%) |

Population ages 45–59 N(%) |

Population ages 60–74 N(%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Gender (male) | 21(56.8) | 4(66.7) | 6(50.0) | 8(53.3) | 3(75.0) |

| Age (M± SD) | 44.1 ± 11.3 | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 38.4 ± 3.8 | 50.6 ± 5.0 | 32.0 ± 1.8 |

| Marital status (single) | 25(67.6) | 5(83.3) | 7(58.3) | 10(66.7) | 3(75.0) |

| Educational level (< bachelor’s degree) | 14(37.8) | 0 | 8(66.7) | 3(20.0) | 3(75.0) |

| Employment status (currently employed) |

8(21.6) |

1(16.7) |

0 |

7(46.7) |

0 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis Schizophrenia Bipolar disorders Major depressive disorder |

13(35.1) 13(35.1) 11(29.7) |

3(50.0) 0 3(50.0) |

6(50.0) 5(41.7) 1(8.3) |

4(26.7) 5(33.3) 6(40.0) |

0 3(75.0) 1(25.0) |

| Addiction | 7(18.9) | 2(33.3) | 3(25.0) | 2(13.3) | 0 |

| Duration of illness, year (M± SD) | 12.2 ± 9.3 | 5.8 ± 3.8 | 12.3 ± 6.3 | 13.7 ± 12.0 | 16.6 ± 8.6 |

| Hospitalization Under constraint |

24(64.9) 4(17.4) |

4(66.7) 0% |

7(58.3) 1(8.3) |

11(73.3) 2(13.3) |

2(50.0) 1(25.0) |

Qualitative analyses

Thematic analysis

An initial reading of the verbatim transcripts identified a number of aspects that characterize patients’ perceptions of the quality of their mental health care. After a second, more in-depth reading, these elements were categorized according to their conceptual similarity into ten themes that covered care organization, activities, the patient’s relatives involvement, information, psychotherapy, relations with other patients, staff relationships, respect and dignity, comfort and drug treatment. All themes were spontaneously raised by respondents.

Computerized text analysis

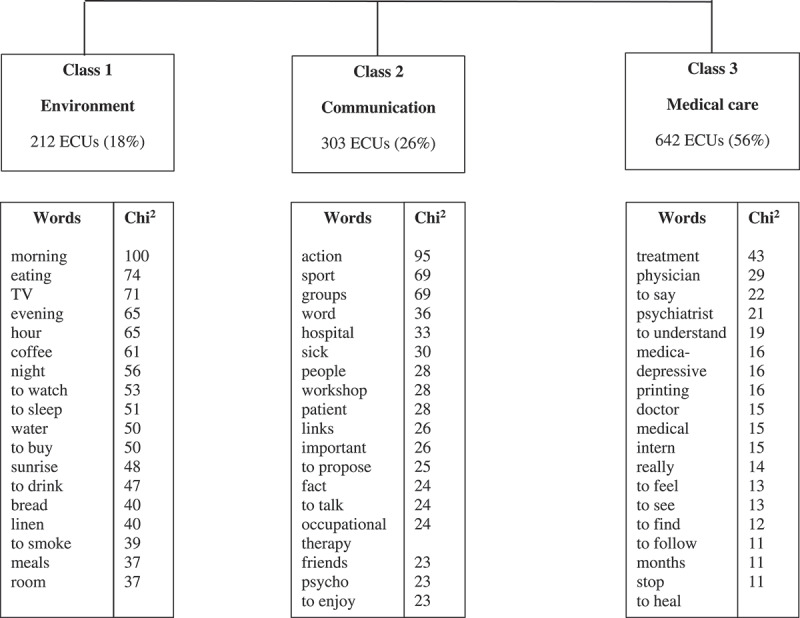

The computerized text analysis reached stability using 1157 ECUs, which corresponds to 70% of the entire initial data corpus. These ECUs were classified into 3 main lexical classes: environment (18% of the classified ECUs), communication (26% of ECUs), and medical care (56% of ECUs). Figure 1 displays these results. These main classes were then subdivided into themes by applying ascending hierarchical classification procedures, which allowed us to highlight the proximity between words within the same class. Most of the themes identified corresponded to those of the thematic analysis, although their wording was slightly different.

Figure 1.

Dendrogram of the descending hierarchical classification

Class 1 (18% of ECUs) reflected the patient’s care environment. This class included characteristic words such as morning (Chi2 = 100), eating (Chi2 = 74), TV (Chi2 = 71), evening (Chi2 = 65), and coffee (Chi2 = 61), etc. This class was divided into four themes: life rhythm, comfort, food and personal space.

Class 2 (26% of ECUs) stressed the importance of communication, and the most significant words included action (Chi2 = 95), sport (Chi2 = 69), groups (Chi2 = 69), word (Chi2 = 36), hospital (Chi2 = 33), etc. Three themes emerged from this class: verbal expression, relationships and activities.

Class 3 (56% of ECUs) referred to the various aspects of patient care as evidenced by the most significant words: treatment (Chi2 = 43), physicians (Chi2 = 29), to say (Chi2 = 22), psychiatrist (Chi2 = 21), to understand (Chi2 = 19), etc. The three themes that emerged from this class were related to actors and follow-up, treatment, and objectives.

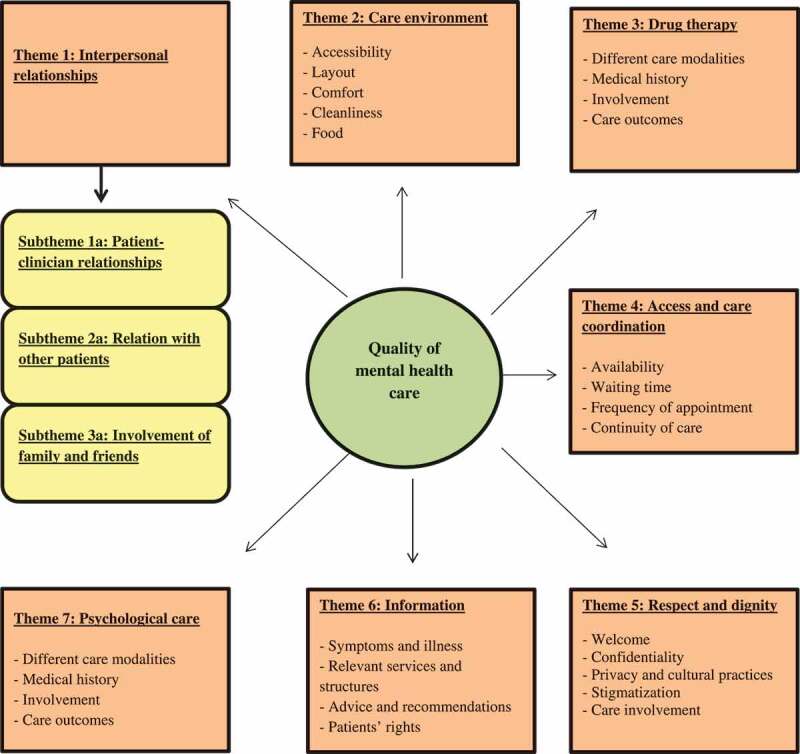

Conceptual framework of quality of mental health care: main themes and subthemes

The results of the two complementary approaches were contrasted and discussed at a meeting between experts in psychiatry and qualitative research. Some themes remained the same, while others were dissociated or combined. The synthesis of these aggregations is presented in Table 4. The final conceptual framework included seven themes that were approved by consensus within the research team (including public health experts, psychiatrists and psychologists [39]): interpersonal relationships (discussed by 100% of interviewees), care environment (95%), drug therapy (92%), access and care coordination (89%), respect and dignity (43%), information (41%), and psychological care (16%). Interpersonal relationships encompassed three subthemes: patient-staff relationships (89%), relations with other patients (68%) and involvement of family and friends (27%). This model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Synthesis of results from thematic analysis and computerized text analysis

| Final themes | Care environment | Access and care coordination | Information | Respect and dignity | Interpersonal relationships | Drug therapy | Psychological care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thematic analysis |

- Comfort - Activities |

- Care organization |

- Information |

- Respect and dignity |

- Relations with other patients - Staff relationships - Patient’s relatives involvement |

- Drug treatment |

- Psychotherapy |

| Computerized text analysis | - Life rhythm - Food - Comfort - Activities - Personal space |

- Actors and follow-up | - Verbal expression - Relationships |

- Treatment - Objectives |

- Verbal expression - Relationships |

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of quality of mental health care

Theme 1: interpersonal relationships (n = 37/37; 100%)

Three subthemes were identified within the patient’s interpersonal relationships: patient-staff relationships, relations with other patients and involvement of family and friends in care.

Subtheme 1a: patient-staff relationships (n = 33/37; 89%)

Almost all patients (89%) mentioned several aspects of the patient-staff relationship as being essential to high-quality care. These aspects included the degree to which the atmosphere was welcoming during admission/consultation. The therapeutic alliance was the cornerstone of patients’ discourse and included building trusting relationships with staff, active collaboration involving commonly defined objectives, listening and understanding, staff reassurance and support, and taking into account the patient as a whole. This theme was the most salient point in the speeches of patients hospitalized under constraint who reported the emotional support and sympathy of the staff, as well as their active listening, as key determinants of quality health care.

‘I was able to realize that nurses were listening, it’s the relational aspect, and the feeling of being listened to’.

(38 years old; male, bipolar disorder; inpatient setting)

Because of the singular nature of the relationship between the patient and his psychologist, ‘staff’ could refer to psychiatrists, nurses, careers, hospital workers, secretaries and social workers, except for the psychologist, whose relationships with the patient were discussed under the theme of psychological care. ‘My psychiatrist listens to me and there has never been any misunderstanding or unfounded authority in the treatment adaptation, we always agree about the change of treatment,[…] we always find a compromise, and I get along very well with her. She has a natural authority, she knows where she is going and she has always been listening. She gives good advice, whether for my jobs or for my life, my family or sentimental life, my personal and private life, but at the same time, she does not play the role of a psychologist’.

(36 years old; female, schizophrenia; outpatient setting)

Subtheme 1b: relations with other patients (n = 25/37; 68%)

Many patients (68%) cited their relationships with other patients as a factor that might influence their perception of the quality of mental health care. Some patients noted that these exchanges can be positive and beneficial by contributing to a better understanding of the illness and the treatment. They can also provide opportunities for mutual support based on the sharing of knowledge and experiences and the provision of emotional, social or practical help within a group of peers.

‘They are beneficial these exchanges […] I have found very sensitive, very intelligent people, who are listening … a good team. In some way, it reassures me because we tell ourselves that we are not the only ones on earth with problems’.

(65 years old; female; schizophrenia; inpatient setting)

Conversely, these interactions can have a negative impact if some patients are agitated or in conflict with others. In this case, patients reported a feeling of insecurity or danger.

‘We find people who are very agitated, really very, very agitated, so when there are heavy cases it’s a little scary’.

(36 years old; female; schizophrenia; outpatient setting)

Subtheme 1 c: involvement of family and friends (n = 10/37; 27%)

A few patients (27%) expressed the need to involve family and friends in their care. More specifically, patients emphasized the importance of providing clear information and explanations to their relatives and of involving them more fully in psychoeducation sessions to help them achieve a better understanding and management of the illness and the treatment. Beyond involvement in the care pathway, patients indicated the need to maintain a social bond with their relatives.

‘There is the family’s involvement in care. The psychologist gave my mother a booklet that she has to fill out with the whole lexical field of care and improvement, so that also helps communication with the family […] Participating in patient-caregiver groups is one of the many groups in which I have participated and it helps to clarify communication’.

(26 years old; male; schizophrenia; outpatient setting)

Theme 2: care environment (n = 35/37; 95%)

The care environment refers to the accessibility, layout and cleanliness of the various places of the health care facility, such as the reception room, waiting room, consultation rooms, wards, dining rooms or sanitary facilities. Patients focused mainly on the comfort of the facilities, but they also emphasized the quality of the basic amenities (TV, telephone, internet, etc.). The tranquility of the places, as well as the measures taken to ensure the respect of privacy and the security of personal property, were also mentioned. Patients also reported the quality, quantity and variety of food. Finally, the establishment of rules and procedures with clear instructions and the provision of specifically designed areas (eg, smoking areas) provide a supportive environment for patient recovery. Patients hospitalized under constraint emphasized the need to have a well-equipped environment offering various activities (workshops, occupational therapy, etc.).

‘Food, being in a single room, it’s true that it’s a luxury […] that it’s clean, there is free TV, I think it’s not bad […] that’s very important and allows us to relax, it’s not noisy’.

(41 years old; female; bipolar disorder; inpatient setting)

Theme 3: drug therapy (n = 34/37; 92%)

Drug therapy is prominent in patients’ discourse (92%). They refer to all the information received about the drug therapy and discuss its time of action, duration and frequency of use, how to deal with side effects, the treatment objectives, and the different options available. Respondents expressed a desire for empowerment with regard to involvement in treatment decisions, such as taking their opinions into account in the treatment choice but also the possibility of refusing a treatment. Many patients reported that the consideration of their medical history by health care providers is a quality criterion, along with the help they receive to deal with bothersome side effects. The impact of drug therapy on the patient’s health status and well-being was also a major issue for most patients. They also emphasized the need for personalized care, which means that particular attention must be paid to their specific needs and expectations. Along with discussing expectations of drug therapy, patients expressed the need to build a relationship of mutual trust with the treating psychiatrist, which is required to achieve patients’ engagement in care.

‘I am lucky to have very good communication with my psychiatrist; she listens to me about what I want or not for treatment […]. If I find myself in a very bad situation, I would allow these physicians to give me a slightly stronger treatment because I feel confidence, and if I do not feel confidence, I would not accept any medication, nothing, anyway. I know that as a patient, we can refuse to take medication’.

(36 years old; female; bipolar disorder; inpatient setting)

Theme 4: access and care coordination (n = 33/37; 89%)

Access and care coordination underpin a broader theme of continuity of care, which is crucial to the management of long-term conditions. These features were suggested several times by many of the patients interviewed (89%). First, the availability of professionals reflects their accessibility when needed, their responsiveness when requested, and their flexibility in scheduling appointments. The promptness of professionals refers to the waiting time before obtaining appointments for consultation and/or hospitalization, as well as the punctuality of professionals. Patients put a high value on the time spent with professionals during encounters. This component reflects the perception of the amount of time available to ask questions as well as the perception of time allowed as an indicator of the level of interest shown by the health care provider. The regularity of follow-up refers to the frequency of meetings with health care providers, while staff consistency relates to the presence of the same actors throughout the patient’s care. Coordination is an essential condition for obtaining quality care. Patients reported this in terms of complementarity between professionals, identification of the role of the different professionals involved in care and the transmission of information between these actors. Patients who have received conflicting information reported that poor quality of care is a manifestation of poor coordination between stakeholders. Patients are sensitive to the provision of personalized care. Emphasis is placed on anticipating and responding to needs, with particular attention to tailoring care based on changes in the patient’s health status. Finally, posthospitalization planning was a major issue for inpatients. Most patients expressed a willingness to participate in the development of their discharge plan. More generally, patients cited external follow-up, that is, the contact they keep with health care providers after discharge, as a key element of successful care delivery. Patients hospitalized under constraint emphasized regularity and availability of health care professionals, as well as preparation and outpatient follow-up as key elements of quality health care.

‘It’s quite well organized, there’s even someone if you need them at any time, I don’t know how it’s handled but it’s well organized […] we are going to be asked how we are feeling regularly. And apparently it’s a lot of meetings and then they go to see everyone’.

(39 years old; male; major depression; inpatient setting)

Theme 5: respect and dignity (n = 16/37; 43%)

Just under half of patients (43%) referred to the respect and dignity that mental health professionals have shown them. This theme encompasses several elements, including the consideration of the individual as a whole, the absence of discrimination and stigmatization, and symmetrical relationships between patients and caregivers. Respect for medical confidentiality and access to medical records were also raised by many patients. Most patients reported difficulties in accessing their medical records when they requested it. Finally, respect for physical intimacy and privacy and respect for cultural and religious practices are factors that promote care and may have an impact on the patient’s perception of quality of their care. Respect for privacy and equality in the therapeutic relationship were the most important aspects for patients hospitalized under constraint.

‘A bad care would be that […] I hope they just have in mind that we are not numbers, I would really like to think that we are in the human dimension’.

(45 years old; male; major depression; inpatient setting)

‘Respect is being in front of therapists who don’t feel superior and who don’t abuse their powers’.

(58 years old; male; major depression; outpatient setting)

Theme 6: information (n = 15/37; 41%)

Almost half of the patients (41%) expressed the need for more complete and understandable medical and nonmedical information. The former refers to information about the illness and its symptomatic manifestations, as well as treatment modalities (such as reasons for care, exam results, side effects of treatment, etc.), while the latter refers to organizational aspects such as the functioning of the service, the relevant services and structures, as well as how to receive emergency assistance and information on patients’ rights. Patients focused on the need to receive more nonmedical information, mainly about their rights and the various support programs available. In addition, some patients mentioned the desire to receive more written information.

‘The doctor who cares for me here, I have seen him quite regularly, with explanations that have been provided each time and additional information if necessary to see more clearly about the origin of the illness, (…), on my treatment but also about the impact that it will have on me, the side effects’.

(38 years old; male; major depression; inpatient setting)

‘They take the time to introduce the place to us, to tell us the rules, the meal times, the space where we can smoke if we smoke, medication administration times, the permission times and where we can go if we want to take a permission’.

(50 years old; male; schizophrenia; outpatient setting)

Theme 7: psychological care (n = 6/37; 16%)

The patient’s psychological care covers the information received about the objectives and conduct of the psychotherapy sessions. Patients reported the beneficial effects of the therapy on their psychological state, as well as on their understanding and management of the illness. Elements more specific to the relationship with the psychologist were discussed, such as the establishment of a trustful relationship, the psychologist’s empathy and understanding, and his or her availability.

‘The psychiatrist suggested it to me, and then I asked to see a psychologist, she untied a lot of things, she helps me a lot. I can talk, she listens to me, she’s really on the human side’.

(48 years old; female; bipolar disorder; outpatient setting)

Discussion

Our study explored the detailed experiences of inpatients and outpatients with severe mental illnesses regarding the quality of their mental health care. Although the experiences of patients hospitalized under constraint may be specific in some respects, this conceptual framework will inform the future development of valid and reliable patient-reported experience measure (PREM) for adult patients with SMIs, regardless of the type of care they receive [39]. This PREM can be shared between different services and health care facilities to carry out routine assessments and establish comparisons at the national level. Despite differences in the symptomatic manifestations of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder, we have not identified any specificity related to these issues in the discourse of the interviewees. The future PREM will be subjected to a field testing which will ensure, in particular, that there is no differential item functioning according to the three pathologies studied (ie, potential bias in the item response) [39,50]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to document the views of these populations in the context of French psychiatric care. The PREM is intended to supplement the range of indicators currently available for measuring and monitoring the quality and performance of the mental health system in France [51]. The assessment of psychiatric care is currently based on the national system for collecting healthcare quality and safety indicators (SQI) related to coordination between hospital and community services, management of somatic care and isolation and restraint practices. We used an original methodology that combined two complementary qualitative approaches to increase the validity of our results. On the one hand, the use of a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) that facilitates qualitative research by offering the possibility of studying large volumes of data in a rigorous and systematic manner [52,53], and on the other hand, Alceste software that minimizes the biases inherent to the researcher’s subjectivity when interpreting data by performing an automated analysis based on the statistical distribution of vocabulary. The final results were thus obtained from these two exploratory approaches, which were applied independently to the text corpus and then juxtaposed and discussed until a consensus was reached within a multidisciplinary research team, which is one of the strengths of our study.

Our study provided an enhanced understanding of what aspects significantly contribute to a positive mental health care experience. Patient interviews revealed the following seven themes: interpersonal relationships, care environment, drug therapy, access and care coordination, respect and dignity, information and psychological care. Our results are consistent, at least in part, with the dimensions identified in the Picker Patient Experience questionnaire (PPE-15), a validated generic measure of patient experience that has been widely used in many studies of quality of care [37,38], covering the following dimensions: information and education, coordination of care, physical comfort, emotional support, respect for patient preferences, involvement of family and friends, and continuity and transition. Some of the dimensions identified in our study were not represented in PPE-15, such as drug treatment and psychological care, which are specific concerns of the experience of psychiatric patients. Moreover, whereas PPE-15 covered the dimension of patient physical comfort (including pain management), this dimension was not a major concern in our results, as the patients interviewed placed more importance on the physical environment in which they were cared for. Additionally, unlike the PPE-15, our study sample focused more on the interpersonal component while distinguishing between relationships with staff, involvement of family and friends, and relationships with other patients. Overall, respondents reported positive experiences, regardless of the care setting and for all the issues raised. Consistent with the literature, the results showed that relationships with care providers were the main factor that could influence the respondents’ experience of care [54]. Indeed, the establishment of a strong therapeutic alliance is a key factor for improving care adherence and medication adherence, which remain major issues for individuals with SMIs [54–57]. Respondents emphasized the importance of being actively listened to, understood and respected by care staff to develop a trusting relationship. Although France has one of the highest densities of psychiatrists in Europe (23 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2017 across all modes of practice combined) [58], considering the ever-increasing administrative tasks, psychiatrists and nursing staffs have a decreasing amount of time to devote directly to their patients. Our results also suggest the development of peer helper interventions in mental health care centers, as patients reported the importance of benefiting from the experience of other patients.

Additionally, to build an atmosphere supportive of the patient’s recovery, the care environment is another important criterion, as it provides space for reassurance and security. This result is also important because care environment savings have been carried out in many French medico-psychological centers in recent decades (with moves and mergers) with new premises that are less accessible or have lower-quality comfort (lower noise or thermal insulation, for example).

Patients with SMIs wanted to be fully informed about their diagnosis and its possible course, and they wanted to know about the advantages and disadvantages of treatment options, whether they were drug-based or psychotherapeutic. This demand is usually addressed in public mental health centers; every patient is supposed to be informed of her/his diagnosis and can receive her/his medical record on demand in less than one week according to Kouchner’s 2002 French law [59]. Patient involvement is an important criterion for improving the outcomes and experience of psychiatric patients over the long term, as studies of shared decision-making in mental health have shown [60]. However, while there is a growing body of evidence supporting a model of care based on a partnership between clinician and patient, shared decision making is difficult to establish over the long term in psychiatry. More specifically, in the context of severe psychiatric illnesses, patients generally have a passive role in the decision-making process [61,62]. Indeed, the issue of the freedom of taking (or not) the treatment and choosing her/his own treatment is a complicated question, as some patients may temporarily be unable to make a decision due to reduced decision-making abilities [63], especially those with mood or psychotic disorders. Some initiatives have been developed to overcome this issue, such as long-acting antipsychotics or psychiatric advanced directives [64].

In addition to the difficulties in accessing and receiving health services [9,10], individuals with SMIs also experience disruptions in the continuity of their care. Although continuity of care is a prerequisite for the provision of high-quality care, deinstitutionalization, the fragmentation of services [65], low retention and a lack of coordination between different services and care providers hamper the continuity of care in mental health. Multiple factors are involved in the management of persons with SMIs, and particular attention should be paid to interprofessional coordination. Indeed, persons who received contradictory information reported poor quality of care. Continuity of care and interprofessional coordination should therefore be priorities for services. Efforts should also be made to keep the public sector attractive in France and increase the retention rate for young psychiatrists and psychologists, who are currently leaving hospitals en masse for the private sector.

Finally, psychological care was not a major concern for respondents. The current guidelines recommend the combined use of medication and psychotherapy in the management of SMIs [66–69]. However, medication remains the preferred first-line treatment in the management of SMIs, over the use of psychotherapy [70], while evidence suggests an increased preference of patients for psychological interventions over medication [71]. This phenomenon may be explained to some extent by the fact that patients may not identify psychotherapy as a need due to a lack of available supply or due to a discrepancy between the available supply and the patient’s demand. Further studies should determine which domain of psychotherapy is expected by patients (such as psychoeducation, symptom-targeted psychotherapy such as behavioral-cognitive therapies, cognitive remediation therapy, mindfulness, positive psychology, gratitude-oriented therapy, etc.). Moreover, unlike psychiatric consultations, psychotherapies are not reimbursed in the private sector in France, and patients with SMIs have lower incomes than the general population, which may also reflect disparities in care access. Experimentations of reimbursement are currently being conducted in four French departments for people with depression or moderate anxiety [72,73].

Strengths and limitations

This study also had several limitations. First, the included patients were recruited from a unique health care facility, which may have resulted in the over- or underexploration of one or more themes related to the particularities of the facility where the study was carried out. However, the sample was diversified and included both inpatients and outpatients with varying backgrounds and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Second, respondents were purposely sampled. Patients were invited to participate in the study by members of the health care team to identify patients who met the inclusion criteria and were sufficiently stable to participate in an interview. Some patients who might have expressed other considerations regarding the quality of their mental health care were not included, such as patients under legal protection measure, those who were not stabilized, etc. These patients, however, represented a minority and did not reflect the target population of this study. Third, the patients’ views were obtained through individual qualitative interviews. Although this is one of the most popular methods in qualitative research, the use of an alternative method, such as focus groups, could have revealed different concerns [72]. Nonetheless, the interviewer was not involved in patient care, and these results were subjected to cognitive debriefing in a subsequent phase, which ensured the comprehensiveness of the data. Fourth, the diagnosis was not retained as a confounding factor because we assumed that these three main disorders were located on the continuum of severe mental disorders for which the quality of care can be assessed comparably. Finally, some concerns may be specific to the French health care system. These results should therefore be interpreted with caution if they are generalized to other countries.

Conclusion

This work provided a conceptual framework that will inform the subsequent development of a patient-reported experience measure to improve and monitor the performance of the mental health care system in France. Consistent with the literature, the results showed the importance that psychiatric patients attribute to the interpersonal component, which is one of the important predictors of therapeutic adherence. Measuring patients’ perception of the quality of care received has become a fundamental prerequisite to support management policies in their objective of continuous service improvement.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- [1].Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476‑93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575‑86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tafalla M, Salvador-Carulla L, Saiz-Ruiz J, et al. Pattern of healthcare resource utilization and direct costs associated with manic episodes in Spain. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Broder MS, Greene M, Chang E, et al. Health care resource use, costs, and diagnosis patterns in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: real-world evidence from US claims databases. Clin Ther. 2018;40(10):1670‑82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mancuso A, Specchia M, Lovato E, et al. Economic burden of schizophrenia: the European situation. A scientific literature review. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(suppl 2). 10.1093/eurpub/cku166.129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Greenberg PE, Fournier -A-A, Sisitsky T, et al. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the USA (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155‑62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality from mental, neurological and substance use disorders in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(2):121‑40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG.. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334‑41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Institute of Medicine . Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. National Academies Press: Washington, DC; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nielssen O, McGorry P, Castle D, et al. The RANZCP guidelines for Schizophrenia: why is our practice so far short of our recommendations, and what can we do about it? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(7):670‑4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys.. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581‑90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Coldefy M, Le Neindre C.. Les disparités territoriales d’offre et d’organisation des soins en psychiatrie en France: d’une vision segmentée à une approche systémique. Paris, France: Institut de Recherche et Documentation en Economie de la Santé (IRDES); 2014. Report no 558. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Basurte-Villamor I, et al. Fernandez del Moral AL, Jimenez-Arriero MA, et al. Diagnostic stability and evolution of bipolar disorder in clinical practice: a prospective cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115(6):473‑80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dassa D, Boyer L, Raymondet P, et al. One or more durations of untreated psychosis? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(6):494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fond G, Boyer L, Andrianarisoa M, et al. Risk factors for increased duration of untreated psychosis. Results from the FACE-SZ dataset. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:529–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lieberman JA, Fenton WS. Delayed detection of psychosis: causes, consequences, and effect on public health. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1727‑30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Csernansky JG, Schuchart EK. Relapse and rehospitalisation rates in patients with schizophrenia: effects of second generation antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(7):473‑84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hamilton JE, Passos IC, de Azevedo Cardoso T, et al. Predictors of psychiatric readmission among patients with bipolar disorder at an academic safety-net hospital. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(6):584‑93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].KEM B-L, Kok GD, Bockting CLH, et al. Effectiveness of psychological interventions in preventing recurrence of depressive disorder: meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:400‑10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hill M, Crumlish N, Clarke M, et al. Prospective relationship of duration of untreated psychosis to psychopathology and functional outcome over 12 years.. Schizophr Res. 2012;141(2–3):215‑21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saarni SI, Viertiö S, Perälä J, et al. Quality of life of people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):386‑94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schürhoff F, Fond G, Berna F, et al. A National network of schizophrenia expert centres: an innovative tool to bridge the research-practice gap. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):728‑35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Henry C, Etain B, Mathieu F, et al. A French network of bipolar expert centres: a model to close the gap between evidence-based medicine and routine practice. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):358‑63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gaebel W, Janssen B, Zielasek J. Mental health quality, outcome measurement, and improvement in Germany. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(6):636‑42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Herbstman BJ, Pincus HA. Measuring mental healthcare quality in the USA: a review of initiatives. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(6):623‑30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Glied SA, Stein BD, McGuire TG, et al. Measuring Performance in Psychiatry: a Call to Action. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(8):872‑8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Parabiaghi A, Bonetto C, Ruggeri M, et al. Severe and persistent mental illness: a useful definition for prioritizing community-based mental health service interventions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(6):457‑63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ruggeri M, Leese M, Thornicroft G, et al. Definition and prevalence of severe and persistent mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(2):149‑55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Trzeciak S, Gaughan JP, Bosire J, et al. Association between medicare summary star ratings for patient experience and clinical Outcomes in US hospitals. J Patient Exp. 2016;3(1):6‑9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang DE, Tsugawa Y, Figueroa JF, et al. Association between the centers for medicare and medicaid services hospital star rating and patient outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):848‑50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Coulter A. Measuring what matters to patients. BMJ. 2017;816. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.j816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].The Beryl Institute . Defining patient experience. [Accessed 2021 Jan 3]. Available at: https://www.theberylinstitute.org/page/DefiningPatientExp

- [33].Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . What is patient experience ? [Accessed 2021 Jan 3]. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/patient-experience/index.html

- [34].Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522‑54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):e001570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fernandes S, Fond G, Zendjidjian X, et al. <p>Measuring the Patient Experience of Mental Health Care: a Systematic and Critical Review of Patient-Reported Experience Measures. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:1‑15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jenkinson C. The Picker Patient Experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):353‑8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Reeves R, et al. Properties of the Picker Patient Experience questionnaire in a randomized controlled trial of long versus short form survey instruments. J Public Health. 2003;25(3):197‑201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fernandes S, Fond G, Zendjidjian X, et al. The Patient-Reported Experience Measure for Improving qUality of care in Mental health (PREMIUM) project in France: study protocol for the development and implementation strategy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:165‑77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rendle KA, Abramson CM, Garrett SB, et al. Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].American Psychiatric Association . DSM-5 : diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20(9):1408‑1416. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fylan F. Semi-structured interviewing. In: Miles J, Gilbert P, editors. Handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. Oxford: UK: Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 65‑77. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237‑46. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‑101. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Welsh E. Using NVivo in the qualitative data analysis process. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2002;3(2): 26. Art. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Reinert M. Une méthode de classification descendante hiérarchique : application à l’analyse lexicale par contexte. Les cahier de l’analyse des données. 1983;8(2): 187‑98. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Reinert M. Alceste une méthodologie d’analyse des données textuelles et une application: Aurelia De Gerard De Nerval. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin De Méthodologie Sociologique. 1990;26(1):24‑54. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rogers HJ. Differential Item Functioning. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, editors. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science.. UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester; 2005. p. 485‑90. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Haute Autorité de Santé. Indicateurs de qualité et de sécurité des soins. Rapport des résultats nationaux de la campagne [Accessed 2020 Apr 16]. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-12/iqss_rapport_complet_2019.pdf.

- [52].Rodik P, Primorac J. To use or not to use: computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software usage among early-career sociologists in Croatia. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2015;16:1. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Banner DJ, Albarrran JW. Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software: a review.. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;19(3):24‑31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Misdrahi D, Verdoux H, Lançon C, et al. The 4-Point ordinal Alliance Self-report: a self-report questionnaire for assessing therapeutic relationships in routine mental health. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(2):181‑5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Llorca P-M. Partial compliance in schizophrenia and the impact on patient outcomes. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161(2):235‑47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sajatovic M, Biswas K, Kilbourne AK, et al. Factors associated with prospective long-term treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(7):753‑9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(5‑6):41‑6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Fernandes S, Coldefy M, Gandré C, et al. L’offre de soins et de services en santé mentale dans les territoires. In: Coldefy M, Gandré C, editors. Atlas de la santé mentale en France. Paris, France: Institut de Recherche et Documentation en Economie de la Santé (IRDES); 2020. p. 15‑50. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Legifrance L, n° 2002–303 du 4 mars 2002 relative aux droits des malades et à la qualité du système de santé; Journal officiel, n° 54 du 5 mars [Accessed 2020 Oct 1]. Available at: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000227015/2020-10-01/

- [60].Alguera-Lara V, Dowsey MM, Ride J, et al. Shared decision making in mental health: the importance for current clinical practice. Australas Psychiatry. 2017;25(6):578‑82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Deegan PE. The lived experience of using psychiatric medication in the recovery process and a shared decision-making program to support it.. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2007;31(1):62‑9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].O’Neal EL, Adams JR, McHugo GJ, et al. Preferences of older and younger adults with serious mental illness for involvement in decision-making in medical and psychiatric settings.. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(10):826‑33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fond G, Bayard S, Capdevielle D, et al. A further evaluation of decision-making under risk and under ambiguity in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;263(3):249‑57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Swanson J, Swartz M, Ferron J, et al. Psychiatric advance directives among public mental health consumers in five U.S. cities: prevalence, demand, and correlates. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2006;34(1):43‑57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Adair CE, McDougall GM, Beckie A, et al. History and measurement of continuity of care in mental health services and evidence of its role in outcomes. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(10):1351‑6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Swartz HA, Swanson J. Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder in Adults: a Review of the Evidence.. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2014;12(3):251‑66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L, et al. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(3):279‑88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Cuijpers P, Noma H, Karyotaki E, et al. A network meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies and their combination in the treatment of adult depression. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):92‑107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Valencia M, Fresan A, Juárez F, et al. The beneficial effects of combining pharmacological and psychosocial treatment on remission and functional outcome in outpatients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(12):1886‑92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gaudiano BA, Miller IW. The evidence-based practice of psychotherapy: facing the challenges that lie ahead. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(7):813‑24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595‑602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Emmanuelli J, Schechter F.. Prise en charge coordonnée des troubles psychiques: état des lieux et conditions d’évolution. Paris: Inspection générale des affaires sociales (IGAS); 2019. Report no 2019-002R. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Guest G, Namey E, Taylor J, et al. Comparing focus groups and individual interviews: findings from a randomized study. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2017;20(6):693‑708. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.