The COVID-19 pandemic has been met by unequal responses in different countries1, 2 and led to unequal impacts, with populations in Europe, the USA, and Latin America disproportionately impacted.3 Science has uncovered much about SARS-CoV-2 and made extraordinary and unprecedented progress on the development of COVID-19 vaccines, but there is still great uncertainty as the pandemic continues to evolve. COVID-19 vaccines are being rolled out in many countries, but this does not mean the crisis is close to being resolved. We are simply moving to a new phase of the pandemic.

What emerges next will partly depend on the ongoing evolution of SARS-CoV-2, on the behaviour of citizens, on governments' decisions about how to respond to the pandemic, on progress in vaccine development and treatments and also in a broader range of disciplines in the sciences and humanities that focus both on bringing this pandemic to an end and learning how to reduce the impacts of future zoonoses, and on the extent to which the international community can stand together in its efforts to control COVID-19. Vaccines alone, unless they achieve high population coverage, offer long-lasting protection, and are effective in preventing both SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19, will not end the pandemic or allow the world to return to “business as usual”. Until high levels of global vaccine-mediated protection are achieved across the world, it could be catastrophic if measures such as mask wearing, physical distancing, and hand hygiene are relaxed prematurely.4 Countries, communities, and individuals must be prepared to cope in the longer-term with both the demands and the consequences of living with such essential containment and prevention measures.

Many factors will determine the overall outcome of the pandemic. A nationalistic rather than global approach to vaccine delivery is not only morally wrong but will also delay any return to a level of “normality” (including relaxed border controls) because no country can be safe until all countries are safe. SARS-CoV-2 could continue to mutate in ways that both accelerate virus transmission and reduce vaccine effectiveness.5, 6, 7 Vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, and disinformation could compromise the global COVID-19 response.8 Naive assumptions about herd immunity, given the appearance of new and challenging SARS-CoV-2 variants,5, 9 could seriously risk repeated outbreaks and recurrences. SARS-CoV-2 can probably never be globally eradicated, because of its presence in many animals (including cats and dogs)10 and because of incomplete vaccine coverage and variable degrees of immunological protection.11 Hence, ongoing strategies to deal with the endemic presence of SARS-CoV-2 in populations over the long term will be needed. Furthermore, we do not yet know if, and when, revaccination with current or new COVID-19 vaccines will be required since the duration of immunological protection and the efficacy against emergent SARS-CoV-2 variants remain unknown. With such uncertainties, we should not assume that recent scientific progress on COVID-19 diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments will end the pandemic. The world is likely to have many more years of COVID-19 decision making ahead—there is no quick solution available at present.

The decisions of global agencies and governments, as well as the behaviours of citizens in every society, will greatly affect the journey ahead. There are many possible outcomes. At one extreme is the most optimistic scenario, in which new-generation COVID-19 vaccines are effective against all SARS-CoV-2 variants (including those that may yet emerge) and viral control is pursued effectively in every country in a coordinated effort to achieve global control. Even with international cooperation and adequate funding, this scenario would inevitably take a long time to achieve. The COVAX initiative is just an initial step towards addressing vaccine equity and global coordination for vaccine access, especially for lower income countries.12 At the other extreme is a pessimistic scenario, in which SARS-CoV-2 variants emerge repeatedly with the ability to escape vaccine immunity, so that only high-income countries can respond by rapidly manufacturing adapted vaccines for multiple rounds of population reimmunisation in pursuit of national control while the rest of the world struggles with repeated waves and vaccines that are not sufficiently effective against newly circulating viral variants. In such a scenario, even in high-income countries, there would probably be repeated outbreaks and the path to “normality” in society and business would be much longer. And there are many other intermediate or alternate scenarios.

Countries that have kept SARS-CoV-2 in check and countries where there are high levels of viral transmission will in time all probably reach a similar destination, even though their paths to arrive there will be quite different, because no countries can remain permanently isolated from the rest of the world. Unfortunately, countries working in isolation from each other and from global agencies will prolong the pandemic. A nationalistic rather than a global approach to COVID-19 vaccine availability, distribution, and delivery will make a pessimistic outcome much more likely. Additionally, unless countries work together to scale up prevention efforts, the risk of other pandemics, or other transboundary disasters with similar consequences, including those fuelled by climate change, will remain a constant threat.

The International Science Council (ISC), as the independent, global voice for science in the broadest sense, believes it is crucial that the range of COVID-19 scenarios over the mid-term and long-term is explored to assist our understanding of the options that will make better outcomes more likely. Decisions to be made in the coming months need to be informed not only by short-term priorities, but also by awareness of how those decisions are likely to affect the ultimate destination. Providing such analyses to policy makers and citizens should assist informed decision making.

In developing its COVID-19 Scenarios Project, the ISC has consulted with WHO and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The ISC has established in February, 2021, a multidisciplinary Oversight Panel made up of globally representative world experts in relevant disciplines to work with a technical team to produce the scenario map. The Oversight Panel will report within 6–8 months to the global community on the possible COVID-19 scenarios that lie ahead over the next 3–5 years, and on the choices that could be made by governments, agencies, and citizens to provide a pathway to an optimistic outcome for the world.

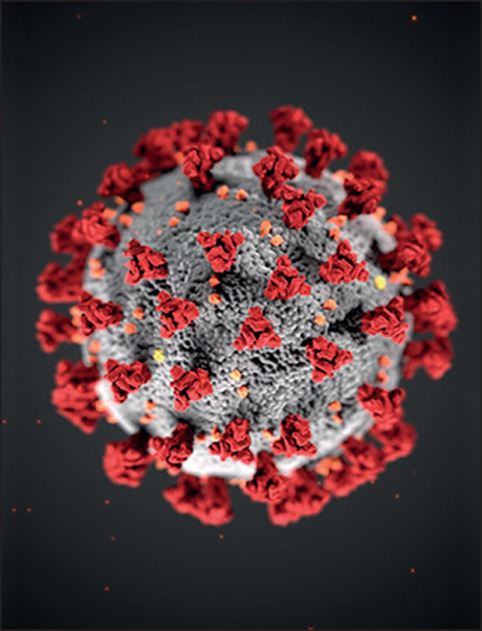

© 2021 CDC/Science Photo Library

Acknowledgments

The authors are members of the Interim COVID-19 Working Group of the ISC. DS is convener of the interim working group. PG is President-Elect of the ISC. GB is a member of the ISC Governing Board. HH is Chief Executive Officer of the ISC. SSAK is Co-chair of the South African Ministerial Advisory Committee on COVID-19. PP has received grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and personal fees as special adviser from the European Commission and as Chair of the Board from the HMG SCOR Board, unrelated to the current project. CW is a member of the working group on pandemics and crisis of the Group of Chief Science Advisors to the European Commission and the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies and has received grants from the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education, the German Federal Ministry for Family and Seniors, the Bertelsmann Foundation, the German Federal Ministry for Health, the German Federal Ministry of Justice and for Consumer Protection, personal fees from Agaplesion gAG as a member of supervisory board, and personal fees from several companies and organisations all unrelated to this Comment. We thank Felicia Low for her help in preparing this Comment.

References

- 1.Brauner JM, Mindermann S, Sharma M, et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abd9338. published online Dec 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen K, Buklijas T, Chen A, et al. International Network for Government Science Advice; Auckland: 2020. Tracking global evidence-to-policy pathways in the coronavirus crisis: a preliminary report.https://www.ingsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/INGSA-Evidence-to-Policy-Tracker_Report-1_FINAL_17Sept.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) 2020. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

- 4.Haug N, Geyrhofer L, Londei A, et al. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Human Behav. 2020;4:1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontanet A, Autran B, Lina B, Kieny MP, Abdool Karim SS, Sridhar D. SARS-CoV-2 variants and ending the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00370-6. published online Feb 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chand M, Hopkins S, Dabrera G, et al. Public Health England; London: 2020. Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: variant of concern 202012/01. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.21.20248640. published online Dec 22. (preprint) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Figueiredo A, Simas C, Karafillakis E, Paterson P, Larson HJ. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: a large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2020;396:898–908. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sridhar D, Gurdasani D. Herd immunity by infection is not an option. Science. 2021;371:230–231. doi: 10.1126/science.abf7921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahdy MAA, Younis W, Ewaida Z. An overview of SARS-CoV-2 and animal infection. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.596391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain S, Batra H, Yadav P, Chand S. COVID-19 vaccines currently under preclinical and clinical studies, and associated antiviral immune response. Vaccines. 2020;8:649. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commissioners of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission. Task Force Chairs and members of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission. Commission Secretariat and Staff of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission Priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic at the start of 2021: statement of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00388-3. published online Feb 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]