A multisystem inflammatory syndrome occurring several weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection and that can include severe acute heart failure has been reported in children (MIS-C).1, 2 In adults with acute severe heart failure, we have identified a similar syndrome (MIS-A) and describe presenting characteristics, diagnostic features, and early outcomes. Our data also complement reports of MIS-A.3

The recognition that three patients presenting with fulminant myocarditis also had clinical features of COVID-19, but were negative for SARS-CoV-2 on RT-PCR, was made during recruitment for a study of patients with cardiac injury associated with SARS-CoV-2. To identify implications for patient care, we audited digital records to identify similar presentations to Barts Health National Health Service (NHS) Trust, London, UK, and Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Trust, London, between March 1, and Sept 30, 2020. As a formal service evaluation, as defined by the UK NHS Health Research Authority, this study did not require review by the Research Ethics Committee. All participants had stored serum for antibody testing, and included nine patients (cases 1–9) with acute cardiac decompensation, negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2, markedly increased serum troponin, and substantially raised inflammatory markers. We also studied three controls (cases 10–12) with acute heart failure and SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, but without all the other features.

Patients were mostly male (seven [78%] of nine), of Black African ancestry (seven [78%] of nine), and the mean age was 36 years (IQR 23–53). Both female patients (cases 6 and 8) presented during or shortly after pregnancy, one of whom had gestational diabetes. One male patient had a significant comorbidity (case 4, hypertension secondary to primary hyperaldosteronism).

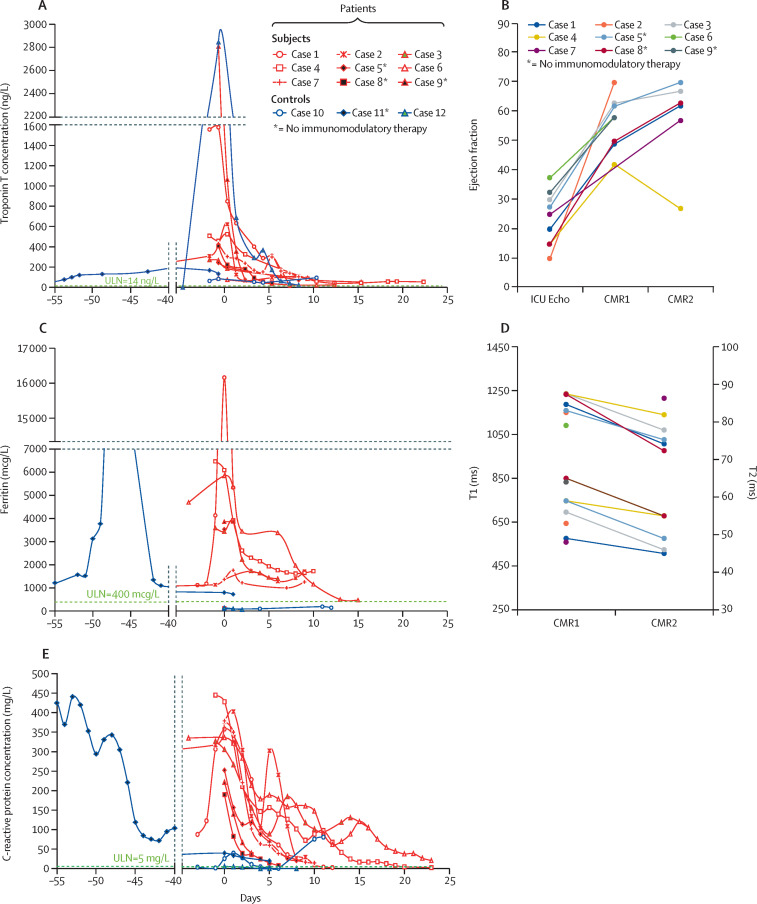

Presenting features in patients included febrile illness (all patients, mean duration of symptoms 3 days [range 1–7]), dyspnoea (five [56%]), gastrointestinal involvement (pain, diarrhoea, or vomiting in eight [89%] patients, with imaging evidence of enteritis in three [38%] of these), pulmonary infiltrates (eight [89%]), and mucocutaneous involvement (four [44%]). A recent history of typical COVID-19 symptoms followed by recovery was present in four (44%) patients, and included RT-PCR-positive infection in one. Patients had multiple negative SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCRs during their cardiac admission (mean 4·6 tests [range 3–8]). SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing on stored serum taken at a mean of 4·2 days (0–20) after admission was positive in seven (78%) patients. Increased C-reactive protein concentration (38–89 times the upper limit of normal [ULN]), ferritin concentration (0·2–16·0) ULN), neutrophil count (1·5–6·6 ULN), and neutrophil count to lymphocyte count ratio (4·5–42·3 ULN) were abnormalities particularly prominent in magnitude (figure ; appendix).

Figure.

Temporal changes in selected markers of systemic inflammation and myocardial damage

Red lines indicate patients (cases 1–9) and blue lines indicate controls (cases 10–12). Panels A, C, and E show biochemical markers. Day 0 represents the timepoint when corticosteroids were administered, or ICU admission for the patients who did not receive steroids. Data from a previous acute COVID-19 admission were available for two cases (cases 2 and 11). Panels B and D show imaging features in patients. Echocardiography was obtained at ICU admission, CMR1 at a mean of 11 days (range 3–24) after ICU admission, and CMR2 103 days (48–155) following CMR1. For echocardiography (B), the median value is used whenever ejection fraction was reported within a range. The highest T1 (left-sided y-axis) and T2 (right-sided y-axis) values reported for each patient are plotted (D). CMR1=acute cardiac MRI. CMR2=convalescent MRI. ICU=intensive care unit. *Patients 5,8, and 9, and control 11 did not receive immunomodulatory therapy.

Patients deteriorated rapidly after admission, including eight (89%) transferring into the tertiary cardiac intensive care unit (ICU) at a mean of 2·9 days after admission (range 1–6 days); one patient (case 5) was transferred to the local ICU 1 day after admission. Therapies included pharmacological (eight [89%] of nine patients]) and mechanical (two [22%]) circulatory support. Corticosteroids (six [67%]) with or without intravenous immunoglobulin (two [33%]) were given frequently, as were broad spectrum antimicrobials (seven [78%]). One patient received anakinra.

Severe left ventricular systolic impairment was present on admission echocardiography with ejection fraction (mean 24% [range 10–35]; figure). Peak troponin concentration ranged between 6 ULN and 208 ULN, and alongside inflammatory markers and clinical status showed rapid improvement following ICU admission and therapy (figure). The mean length of ICU stay was 9 days (2–25 days).

Acute cardiac MRI (CMR1), available for all patients at a mean of 11 days (range 3–24) following ICU admission, showed left ventricular ejection fraction of 57% (42–70). Late gadolinium enhancement (six [67%] of nine patients), increased T1 signal (seven [100%] of seven), and increased T2 signal (six [67%] of nine) were present in most patients (figure). Convalescent MRI (CMR2) in six patients done 103 days (48–155) following CMR1 detected a left ventricular ejection fraction in the normal range in all patients except case 4, in whom systolic function again deteriorated. Comparing paired data, left ventricular ejection fraction recovered markedly between admission and CMR1 (22% vs 53%; p<0·0001), but was similar between CMR1 and CMR2 (53% vs 58%; p=0·42). Abnormal late gadolinium enhancement (four [67%] of six vs one [17%] of six), T1 (six [100%] of six vs four [67%] of six), and T2 (four [80%] of five vs one [20%] of five) were less frequent on CMR2 than on CMR1 (mean paired data: T1 1210 ms to 1044 ms; p=0·004; T2 58 ms to 50 ms; p=0·007). T1 and T2 signals remained increased in case 4.

We suggest that this series describes cardiogenic shock due to a MIS-A after COVID-19. Similarities with patients with MIS-C include frequent gastrointestinal involvement, pulmonary infiltrates, mucocutaneous involvement, and significantly increased inflammatory markers.1, 2 Detectable antibody and RNA absence is consistent with recent recovery following SARS-CoV-2 infection in London before March, 2020. Not all patients had detectable SARS-CoV-2 antibody, another feature that is common to MIS-C, and one with important clinical implications. A preponderance of male patients and patients from minority ethnic groups in the UK mark another similarity with MIS-C. As is similar in patients with MIS-C, a rapid and profound improvement in cardiac function closely followed initiation of supportive, antimicrobial, or immunomodulatory therapy.

The three controls helped define the key features of cardiogenic shock in patients with MIS-A, and illustrate diagnostic challenges arising from the heterogeneous causes of acutely presenting heart failure. Presenting within weeks of SARS-CoV-2 infection, none showed extreme increases in inflammatory markers, gastrointestinal symptoms, or mucocutaneous features. Only one control (case 12) had greatly increased cardiac troponin concentration, and had lymphocytic myocarditis with parvovirus on biopsy. With increasing population seropositivity, the control findings also emphasise that anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG will make little contribution to the diagnosis of MIS-A.

Our study's limitations include selection bias. Notably, lethal and milder cases of MIS-A were not represented. All therapeutic interventions were uncontrolled and causality was not inferred. Two patients were negative for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, consistent with seropositivity prevalence in patients with MIS-C.1, 2 This finding might reflect test sensitivity, failed or delayed seroconversion, or early declines in antibody concentrations. Alternatively, initiating events other than SARS-CoV-2 might be responsible.

However, the primary purpose of this Correspondence is to highlight a novel clinical presentation of a multisystem disorder that can have life-threatening features, yet might respond adroitly to therapy. Potential factors responsible for the delay in identifying this syndrome in adults or diagnosing individual patients include: (1) severe cardiac involvement is likely to be rare, (2) negative RT-PCR testing at the time of the cardiac presentation, (3) limited diagnostic role for antibody testing (unavailable early in the pandemic and poor specificity subsequently), (4) attribution of systolic impairment to pre-existing cardiac disease, (5) high frequency of COVID-19-related acute myocardial injury and multiplicity of its causes (up to 40% of hospitalised patients have increased troponin concentrations4), and (6) difficulties obtaining complex or invasive diagnostic investigations in ICU patients during the pandemic. Finally, as MIS-C is a wide-spectrum disorder, including variable severity and involving multiple systems,2 adult practitioners should also be alert to the likelihood that MIS-A will be heterogenous and might not include cardiac involvement.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. RB and HCS contributed equally. This study was not externally funded. An associated study (ROAD-COVID19, NCT04340921) is supported by British Heart Foundation accelerator award AA/18/5/34222.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valverde I, Singh Y, Sanchez-de-Toledo J, et al. Acute cardiovascular manifestations in 286 children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection in Europe. Circulation. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050065. published online Nov 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, et al. case series of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection—United Kingdom and United States, March–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Report. 2020;69:1450–1456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1666–1687. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.