Abstract

Background: Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) epidemic is spreading globally. Sex differences in the severity and mortality of COVID-19 emerged. This study aims to describe the impact of sex on outcomes in COVOD-19 with a special focus on the effect of estrogen.

Methods: We performed a retrospective cohort study which included 413 patients (230 males and 183 females) with COVID-19 from three designated hospitals in China with a follow up time from January 31, 2020, to April 17, 2020. Women over 55 were considered as postmenopausal patients according to the previous epidemiological data from China. The interaction between age and sex on in-hospital mortality was determined through Cox regression analysis. In addition, multivariate Cox regression models were performed to explore risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality of COVID-19.

Results: Age and sex had significant interaction for the in-hospital mortality (P < 0.001). Multivariate Cox regression showed that age (HR 1.041, 95% CI 1.009–1.073, P = 0.012), male sex (HR 2.033, 95% CI 1.007–2.098, P = 0.010), the interaction between age and sex (HR 1.118, 95% CI 1.003–1.232, P = 0.018), and comorbidities (HR 9.845, 95% CI 2.280–42.520, P = 0.002) were independently associated with in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 patients. In this multicentre study, female experienced a lower fatality for COVID-19 than male (4.4 vs. 10.0%, P = 0.031). Interestingly, stratification by age group revealed no difference in-hospital mortality was noted in women under 55 compared with women over 55 (3.8 vs. 5.2%, P = 0.144), as well as in women under 55 compared with the same age men (3.8 vs. 4.0%, P = 0.918). However, there was significantly difference in women over 55 with men of the same age group (5.2 vs. 21.0%, P = 0.007). Compared with male patients, female patients had higher lymphocyte (P < 0.001) and high-density lipoprotein (P < 0.001), lower high sensitive c reaction protein level (P < 0.001), and lower incidence rate of acute cardiac injury (6.6 vs. 13.5%, P = 0.022).

Conclusion: Male sex is an independent risk factor for COVID-19 in-hospital mortality. Although female mortality in COVID-19 is lower than male, it might not be directly related to the effect of estrogen. Further study is warranted to identify the sex difference in COVID-19 and mechanisms involved.

Keywords: COVID-19, sex, estrogen, menopause, mortality, China

Introduction

The whole world is currently under the effect of the ongoing epidemic of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), caused by a novel coronavirus termed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). As of 17 June 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported 8,061,520 confirmed cases and 440,290 deaths in 216 countries and regions, and COVID-19 has become a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) (1). Although most of the COVID-19 patients are non-severe and self-limited, there are still 16% severe cases and 3.1% died in China (2–5).

The current studies showed that advanced age and comorbidities were closely related to worse prognosis (6–9). Recently a retrospective multicentre cohort study demonstrated older COVID-19 patients tended to have relatively more severe clinical infections and poorer clinical outcomes associated with COVID-19 compared with younger patients in Jiangsu of China (10). In addition, in a multicentre Italian CORIST study including 3,894 patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection found advanced age at hospital admission was one of powerful predictors of higher in-hospital death (11). Meanwhile, evidence of sex differences in COVID-19 severity emerged, where the morbidity and mortality were all higher among males than females (12–14). A male bias in COVID-19 mortality was reported in 37 of the 38 countries that have provided sex-disaggregated data. Scully et al. showed that the average male case fatality rate (CFR) across 38 countries was 1.7 times higher than the average female CFR (15). Previous epidemiological studies showed the proportion of individuals infected and CFRs in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV were higher in males than that of females (16, 17). The causes of Sex differences following virus infections are multifactorial, including differences in steroid hormones, immune response X-linked genes, disease-susceptibility genes in sexes, and gender-related social factors (18–20).

Studies have linked increased susceptibility to infection with circulating steroid hormone concentrations (18, 19, 21). Traditionally, sex steroid hormones, especially the estrogen in females, have been considered for their immunomodulatory properties. Animal study indicated that ovariectomy or treating female mice with estrogen receptor antagonist increased mortality, indicating a protective effect for estrogen receptor signaling in mice infected with SARS-CoV (22). Thus, the lower incidence of severe COVID-19 in female patients might be related to the protective effect of estrogen. However, as yet, few studies have focused on sex differences in clinical characteristics and laboratory tests of COVID-19, especially whether estrogen affects the occurrence and development of COVID-19. Therefore, this study aims to analysis the sex differences on clinical characteristics, severity and mortality in adult patients with COVID-19, and explore possible mechanisms, with a special focus on premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

The multicentre retrospective cohort study was conducted at three hospitals designated for the treatment of COVID-19, including Jinan Infectious diseases Hospital in Shandong, Shandong Provincial Chest Hospital in Shandong, and Huanggang Central Hospital in Hubei. The recruitment period was from January 31, 2020, to April 17, 2020. The diagnosis of COVID-19 was made based on the National Health Commission of China guidance (23). The presence of SARS-COV-2 in respiratory specimens was confirmed using real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay were performed in accordance with the protocol described previously (2). The patients that are pregnant or <18 years old were excluded. As of April 17, 2020, all included patients were discharged or died. In addition, the vast majority of city women were postmenopausal by age 55 (24, 25), according to the previous epidemiological data from China, which was consistent with our study. Thus, patients were divided into two groups according to the age of 55 to explore the role of estrogen in the progression of COVID-19. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Jinan Infectious diseases Hospital, Shandong Provincial Chest Hospital, and Huanggang Central Hospital.

Data Collection

Two physicians reviewed clinical electronic medical records and laboratory findings for all patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, and then a third researcher determined any differences between interpretations of the two primary reviewers. The demographic data, menstrual history of women, clinical characteristics and laboratory results were collected at admission. We also evaluated and gathered complications, treatment and clinical outcomes (discharged alive or dead) at the end of study, by using a standardized case-report form. For patients with a readmission during the study period, data from the first admission were presented. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were calculated using the worst value of physiological variables within 24 h of presentation.

Diagnostic and Grading Criteria for COVID-19

The disease severity of COVID-19 patients was divided into severe and non-severe conditions, defined according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia (26). Severe COVID-19 should reach the following either one major criterion or three or more minor criteria. In detail, Minor criteria included respiratory rate more than 30 breaths per minute, PaO2/FIO2 ratio lower than 250, multilobar infiltrates confusion or disorientation, blood urea nitrogen level more than 7.1 mmol/L, white blood cell count <4.0 × 109 per L, platelet count <100 × 1012 per L, core temperature lower than 36°C, and hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation. Major criteria included septic shock with need for vasopressors, or mechanical ventilation. Fever was defined as axillary temperature of at least 37.3°C. Septic shock was defined according to the 2016 Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock (27). Acute kidney injury was diagnosed according to the KDIGO clinical practice guidelines (28) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) was diagnosed according to the Berlin Definition (29). Acute cardiac injury was diagnosed if serum levels of cardiac biomarkers (e.g., high-sensitive cardiac troponin I) were above the 99th percentile upper reference limit, or if new abnormalities were shown in electrocardiography and echocardiography (2).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcomes were including disease severity, development of acute respiratory distress (ARDS), acute cardiac injury, acute liver injury, sepsis shock and acute kidney injury (AKI).

Statistical Analysis

Patients were divided into two groups according to sex, and the subgroup analysis was performed at the cut-off point of 55 years old according to the age of menopause in women. Female patients and male patients were grouped by age into the younger group(less than or 55 years old) and the older group (above 55 years old) for comparison. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or medians (interquartile range, IQR) values. Categorical data were summarized as frequency rates and percentages. The comparison between the two groups was conducted using t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables, and chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. The interaction between age and sex on in-hospital mortality was determined through Cox regression analysis. In addition, multivariate Cox regression models were performed to explore risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality of COVID-19. Considering the total number of death cases (n = 31) in this study and to avoid overfitting in the model, four factors with significant association with mortality in univariate regression analyses (sex, age, the interaction between age and sex, and comorbidities) were chosen for multivariate analysis on the basis of previous findings and clinical constraints (8, 10, 12, 13, 30). Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and the corresponding P values were calculated for each risk factor. Kaplan-Meier estimator was generated to estimate the survival curves and log-rank test was used to compare the survival probability between male and female groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The variables that had >5% of values missing were excluded. Simple data imputation was done for missing data <5%, using the median for skewed distribution data, or the mode for dichotomous data. All analyses were conducted with SPSS software, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Results

Basic Characteristics

A total of 441 COVID-19 patients (range, 2–89 years) were hospitalized in the three designated hospital from Jan 31, 2020 to Apr 17, 2020. After excluding one pregnant patient, 11 patients <18 years old, and 16 patients without available key information in their medical records, we included 413 patients in the final analysis, among whom 230 were males and 183 were females. Table 1 presented the sex-specific demographic and clinical characteristics of the all patients with COVID-19. The median age of all cases was 58 years old (IQR 47–67 years), and it had not difference between males and females. Comorbidities were common for both sexes, but no significant difference. Regarding the symptoms, fever, cough and chest distress were the most common on admission among both men and women. However, a higher percentage of men had fever (90.4% vs. 82.0%, P = 0.012). Additionally, SOFA score differed significantly between males and females.

Table 1.

Sex-specific demographic and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients.

| Variables | Male (n = 230) | Female (n = 183) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Median (IQR),y | 56 (46, 67) | 59 (49, 67) | 0.094 |

| current or ever smoking | 18 (7.8) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Drinking | 17 (7.4) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| COPD | 6 (2.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0.139 |

| DM | 30 (13.0) | 24 (13.1) | 0.983 |

| Hypertension | 70 (30.4) | 47 (25.7) | 0.287 |

| Heart disease | 15 (6.5) | 11 (6.0) | 0.832 |

| Kidney disease | 6 (2.6) | 4 (2.2) | 0.781 |

| Liver disease | 7 (3.0) | 5 (2.7) | 0.851 |

| Shock | 8 (3.5) | 6 (3.3) | 0.911 |

| Tumor | 6 (2.6) | 7 (3.8) | 0.482 |

| Immune disease | 4 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 0.744 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Fever | 208 (90.4) | 150 (82.0) | 0.012 |

| Cough | 178 (77.4) | 142 (76.1) | 0.961 |

| Expectoration | 81 (35.2) | 57 (31.1) | 0.384 |

| Chest distress | 110 (47.8) | 92 (50.2) | 0.621 |

| Chest pain | 5 (2.2) | 8 (4.4) | 0.204 |

| Hemoptysis | 4 (1.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0.697 |

| Headache | 12 (5.2) | 11 (6.0) | 0.727 |

| Myalgia | 24 (10.4) | 24 (13.1) | 0.399 |

| Fatigue | 83 (36.1) | 71 (38.8) | 0.571 |

| Gastrointestinal | 33 (14.3) | 35 (19.1) | 0.193 |

| SOFA Score, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.022 |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NS, no significance; DM, diabetes mellitus; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Laboratory Results

Some laboratory results at admission showed significant differences between male and female patients (P < 0.05). Male cases had substantially increased hemoglobin, alanine amino transferase (ALT), creatinine, creatine kinase, creatine kinase isoenzyme-MB (CK-MB), and procalcitonin, while significantly decreased lymphocyte counts, platelet counts, total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Compared to men, women have lower scrum high sensitive c reaction protein (HS-CRP) levels (P < 0.001). The sex-specific laboratory results of the 413 patients with COVID-19 were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sex-specific laboratory results of COVID-19 patients.

| Variables | Normal Range | Male (n = 230) | Female (n = 183) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell (×109/L) | 3.5–9.5 | 7.90 (6.68, 10.2) | 7.61 (6.54, 9.81) | 0.172 |

| Neutrophil (×109/L) | 1.8–6.3 | 6.13 (4.90, 8.37) | 5.98 (4.67, 8.55) | 0.434 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/L) | 1.1–3.2 | 1.23 (1.0, 1.62) | 1.36 (1.11, 1.72) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 316–354 | 130 (123, 139) | 117 (108, 124) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 125–350 | 251 (220, 313) | 265 (233, 313) | 0.030 |

| D-dimer (μg/ml) | 0–1.5 | 0.80 (0.43, 2.06) | 0.92 (0.43, 2.25) | 0.483 |

| ALT (U/L) | 9–50 | 36 (22, 53) | 22 (15, 35) | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 120–250 | 344 (286, 446) | 334 (278, 419) | 0.165 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 0–7 | 8.34 (6.08, 11.6) | 8.47 (6.59, 10.6) | 0.316 |

| Prealbumin (mg/L) | 200–430 | 125 (77, 169) | 122 (83, 176) | 0.842 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40–55 | 30.2 (27.0, 33.8) | 30.6 (27.3, 34.9) | 0.184 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0–26 | 12.0 (9.28, 17.2) | 11.8 (9.15, 15.3) | 0.316 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 57–97 | 77.6 (68.6, 91.7) | 56.9 (50.9, 67.0) | <0.001 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 0–190 | 96.0 (62.3, 174) | 58.0 (38.5, 95.0) | <0.001 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 0–24 | 15.0 (11.0, 19.0) | 13.0 (10.0, 16.0) | <0.001 |

| HS-CRP (mg/L) | 0–3 | 55.8 (19.3, 115) | 25.3 (5.28, 60.9) | <0.001 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0–0.05 | 0.05 (0.05, 0.14) | 0.05 (0.05, 0.07) | <0.001 |

| Troponin (pg/ml) | 0–28 | 4.95 (2.00, 15.2) | 4.90 (2.0, 14.8) | 0.756 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.3–5.2 | 3.52 (3.03, 4.13) | 3.79 (3.26, 4.35) | 0.003 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.29–1.55 | 0.86 (0.70, 1.02) | 1.02 (0.84, 1.20) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.1–3.37 | 2.06 (1.62, 2.55) | 2.05 (1.61, 2.55) | 0.849 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.51–1.70 | 1.69 (1.49, 2.06) | 1.77 (1.55, 2.17) | 0.051 |

| ESR (mm/H) | 0–15 | 47.4 (32.8, 63.0) | 51.5 (38.5, 67.4) | 0.110 |

Data are median (IQR). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ALT, alanine amino transferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IL-6, interleukin-6; CK-MB, creatine kinase isoenzyme-MB; HS-CRP, high sensitive c reaction protein; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Clinical Outcomes

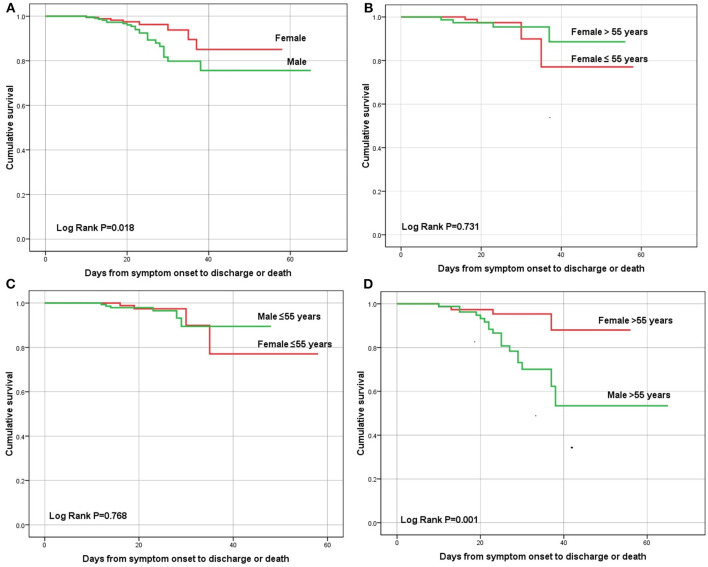

The total of 31 patients (7.5%) died during hospitalization. Figure 1 showed the sex-specific mortality in different age patients. The in-hospital mortality rate was 10.0% for men and 4.4% for women (P = 0.031). The cumulative survival rate was significantly different between males and females (P = 0.018, log-rank test; Figure 2A). In the overall population, 91 cases (22.0%) were diagnosed as severe condition. Although there was no significant difference in the severity of COVID-19 between males and females, severe cases were more likely to be seen in men than women (24.3 vs. 19.1%, P = 0.203). There were no sex differences in development of ARDS, sepsis shock, acute kidney injury or acute liver injury (Table 3). However, compared with males, females were less likely to develop acute cardiac injury (6.6 vs. 13.5%, P = 0.022, Table 3).

Figure 1.

Sex-specific in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 patients and subgroup stratified by age of 55 years. * P < 0.05 vs. male by chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests.

Figure 2.

Kalpan-Meier survival curve of male and female patients with COVID-19 in (A) male vs. female, (B) age ≤ 55 years vs. age > 55 years in female patients, (C) male vs. female in age ≤ 55 years old group, and (D) male vs. female in age > 55 years old group by log-rank test for all.

Table 3.

Sex-specific clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients.

| Clinical outcomes | Male (n = 230) | Female (n = 183) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diease severity | |||

| Non-severe | 174 (75.7) | 148 (80.9) | – |

| Severe | 56 (24.3) | 35 (19.1) | 0.203 |

| ARDS | 62 (27.0) | 40 (21.9) | 0.233 |

| Time from symptom onset to ARDS, Median(IQR),d | 11 (8, 16) | 12 (8, 15) | 0.748 |

| Sepsis shock | 22 (9.6) | 12 (6.6) | 0.269 |

| Time from symptom onset to shock, Median(IQR),d | 18 (13, 24) | 17 (13, 23) | 0.810 |

| AKI | 18 (7.8) | 10 (5.5) | 0.343 |

| Time from symptom onset to AKI, Median(IQR),d | 20 (14, 25) | 17 (13, 22) | 0.440 |

| Acute liver injury | 33 (14.3) | 18 (9.8) | 0.166 |

| Time from symptom onset to acute liver injury, Median(IQR),d | 17 (11, 23) | 15 (11, 19) | 0.840 |

| Acute cardiac injury | 31 (13.5) | 12 (6.6) | 0.022 |

| Time from symptom onset to acute cardiac injury, Median(IQR),d | 17 (11, 23) | 16 (11, 21) | 0.906 |

| In-hospital mortality | 23 (10.0) | 8 (4.4) | 0.031 |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR, inter quartile range; AKI, acute kidney injury. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Multivariate Cox Regression of In-hospital Mortality

Age and sex had significant interaction for the in-hospital mortality (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Multivariate Cox regression analysis suggested increased in-hospital mortality was associated with age (HR 1.041, 95% CI 1.009–1.073, P = 0.012), male sex (HR 2.033, 95% CI 1.007–2.098, P = 0.010), the interaction between age and sex (HR 1.118, 95% CI 1.003–1.232, P = 0.018), and comorbidities (HR 9.845, 95% CI 2.280–42.520, P = 0.002) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cox regression models evaluating risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients.

| Variables | Univariate Cox regression |

Multivariate Cox regression Model 1 |

Multivariate Cox regression Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.054 (1.023–1.087) | 0.001 | 1.056 (1.026–1.085) | 0.001 | 1.041 (1.009–1.073) | 0.012 |

| Age >55 yrs (vs. Age ≤ 55 yrs) | 3.755 (1.719–8.205) | 0.001 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male (vs. female) | 2.431 (1.061–5.570) | 0.031 | 2.027 (1.010–2.043) | 0.028 | 2.033 (1.007–2.098) | 0.010 |

| Age × Sex | 1.610 (1.276–2.030) | <0.001 | 1.206 (1.002–1.358) | 0.026 | 1.118 (1.003–1.232) | 0.018 |

| Comorbidities | 30.727 (9.125–103.461) | <0.001 | 9.845 (2.280–42.520) | 0.002 | ||

| Median time from symptom onset to admission, d | 0.672 (0.543–1.384) | 0.396 | ||||

| Lymphocyte | 0.164 (0.052–0.518) | 0.002 | ||||

| HS-CRP | 1.007 (0.992–1.023) | 0.353 | ||||

| Procalcitonin | 1.151 (1.007–1.314) | 0.039 | ||||

| D-dimer | 1.016 (0.991–1.040) | 0.210 | ||||

| Troponin | 1.002(0.996–1.009) | 0.487 | ||||

| TC | 0.889 (0.524–1.508) | 0.663 | ||||

| HDL | 1.356 (0.365–5.041) | 0.649 | ||||

| SOFA | 1.881 (1.546–2.289) | <0.001 | ||||

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HS-CRP, high sensitive c reaction protein; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. Comorbidities were defined as having at least one of the followings before diagnosis of COVID-19: chronic obstructive; pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, stroke, tumor, autoimmune disease, and HIV infection. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Subgroup Analysis

As mentioned earlier, female patients were divided into premenopausal and postmenopausal groups at the age of 55, and subgroup analysis was performed at the cut-off point of 55 years old. No differences on in-hospital mortality were noted in premenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women (3.8 vs. 5.2%, P = 0.144, Figure 1). In addition, subgroup analysis revealed no differences in-hospital mortality were noted in premenopausal women compared with men (3.8 vs. 4.0%, P = 0.918), but differed significantly in postmenopausal women with men older than 55 (5.2 vs. 21.0%, P = 0.007). Additionally, no difference in cumulative survival rate was noted in premenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women (P = 0.731, log-rank test; Figure 2B), as well as premenopausal women compared with men younger than 55(P = 0.768, log-rank test; Figure 2C), but differed significantly in postmenopausal women with men older than 55(P = 0.001, log-rank test; Figure 2D).

In the subgroup analysis, acute liver injury and acute cardiac injury were less observed complications in women than men older than 55 (10.4 vs. 24.7%, P = 0.019; 9.1 vs. 25.9%, P = 0.006, respectively). However, the median duration from onset of symptoms to complications had no difference between sexes. Compared with male patients, female patients had higher lymphocyte (P < 0.001) and high-density lipoprotein (P < 0.001), lower high sensitive c reaction protein level (P < 0.001), and lower incidence rate of acute cardiac injury (6.6 vs. 13.5%, P = 0.022). The sex differences of clinical characteristics and outcomes were shown in Tables 5–7.

Table 5.

Sex-specific demographic and clinical characteristics for subgroup stratified by 55 years in COVID-19 patients.

| Variables | Age ≤ 55 Y (n = 255) | Age > 55 Y (n = 158) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 149) | Female (n = 106) | P-value | Male (n = 81) | Female (n = 77) | P-value | |

| Age, Median(IQR), y | 47 (37, 51) | 46 (38, 50) | 0.494 | 66 (61, 71) | 66 (62, 73) | 0.280 |

| current or ever smoking | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 0.078 | 13 (16.0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Drinking | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0.043 | 9 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| COPD | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | NS | 5 (6.2) | 1 (1.3) | 0.236 |

| DM | 7 (4.7) | 4 (3.8) | 0.720 | 23 (28.4) | 20 (26.0) | 0.733 |

| Hypertension | 13 (8.7) | 6 (5.7) | 0.358 | 57 (70.4) | 41 (53.2) | 0.027 |

| Heart disease | 3 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0.943 | 12 (14.8) | 9 (11.7) | 0.563 |

| Kidney disease | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.9) | NS | 5 (6.2) | 3 (3.9) | 0.772 |

| Liver disease | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.9) | NS | 5 (6.2) | 3 (3.9) | 0.772 |

| Shock | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | NS | 7 (8.6) | 6 (7.8) | 0.846 |

| Tumor | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.9) | NS | 5 (6.2) | 6 (7.8) | 0.689 |

| Immune disease | 2(1.3) | 2(1.9) | NS | 2(2.5) | 2(2.6) | NS |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Fever | 141 (94.6) | 86 (81.1) | 0.001 | 67 (82.7) | 64 (83.1) | 0.947 |

| Cough | 114 (76.5) | 82 (77.4) | 0.874 | 64 (79.0) | 60 (77.9) | 0.868 |

| Expectoration | 56 (37.6) | 32 (30.2) | 0.221 | 25 (30.9) | 25 (32.5) | 0.829 |

| Chest distress | 62 (41.6) | 43 (40.6) | 0.867 | 48 (59.3) | 49 (63.6) | 0.572 |

| Chest pain | 3 (2.0) | 4 (3.8) | 0.646 | 2 (2.5) | 4 (5.2) | 0.632 |

| Hemoptysis | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.9) | NS | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) | NS |

| Headache | 9 (6.0) | 7 (6.6) | 0.855 | 3 (3.7) | 4 (5.2) | 0.945 |

| Myalgia | 15 (10.1) | 13 (12.3) | 0.580 | 9 (11.1) | 11 (14.3) | 0.549 |

| Fatigue | 53 (35.6) | 32 (30.2) | 0.369 | 30 (37.0) | 39 (50.6) | 0.085 |

| Gastrointestinal | 19 (12.8) | 17 (16.0) | 0.458 | 14 (17.3) | 18 (23.4) | <0.001 |

| SOFA Score, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.189 | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.009 |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NS, no significance; DM, diabetes mellitus; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Table 7.

Sex-specific clinical outcomes for subgroupstratified by 55 years in COVID-19 patients.

| Clinical outcomes | Age ≤ 55 Y (n = 255) | Age > 55 Y (n = 158) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 149) | Female (n = 106) | P-value | Male (n = 81) | Female (n = 77) | P-value | |

| Disease severity | ||||||

| Non-severe | 128 (85.9) | 93 (87.7) | – | 46 (56.8) | 55 (71.4) | – |

| Severe | 21 (14.1) | 13 (12.3) | 0.672 | 35 (43.2) | 22 (28.6) | 0.055 |

| ARDS | 25 (16.8) | 14 (13.2) | 0.435 | 37 (45.7) | 26 (33.8) | 0.126 |

| Time from symptom onset to ARDS, Median (IQR), d | 9 (7, 12) | 11 (7, 16) | 0.181 | 13 (8, 17) | 12 (8, 16) | 0.484 |

| Sepsis shock | 1 0 (6.7) | 7 (6.6) | 0.973 | 12 (14.8) | 5 (6.5) | 0.092 |

| Time from symptom onset to shock, Median (IQR), d | 17 (11, 20) | 23 (14, 33) | 0.244 | 18 (14, 25) | 18 (13, 23) | 0.828 |

| AKI | 5 (3.4) | 4 (3.8) | 0.859 | 13 (16.0) | 6 (7.8) | 0.111 |

| Time from symptom onset to AKI, Median (IQR), d | 20 (13, 22) | 22 (21, 23) | 0.438 | 16 (13, 22) | 18 (14, 26) | 0.374 |

| Acute liver injury | 13 (8.7) | 10 (9.4) | 0.846 | 20 (24.7) | 8 (10.4) | 0.019 |

| Time from symptom onset to acute liver injury, Median (IQR), d | 13 (10, 16) | 13 (8, 22) | 0.657 | 16 (13, 22) | 17 (12, 23) | 0.972 |

| Acute cardiac injury | 10 (6.7) | 5 (4.7) | 0.505 | 21 (25.9) | 7 (9.1) | 0.006 |

| Time from symptom onset to acute cardiac injury, Median (IQR), d | 15 (10, 18) | 18 (17, 21) | 0.145 | 16 (11, 23) | 14 (9, 22) | 0.202 |

| In-hospital mortality | 6 (4.0) | 4 (3.8) | 0.918 | 17 (21.0) | 4 (5.2) | 0.007 |

Data are n (%) unless specified otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR, inter quartile range; AKI, acute kidney injury. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Table 6.

Sex-specific laboratory results for subgroup stratified by 55 years in COVID-19 patients.

| Variables | Normal range | Age ≤ 55 Y (n = 255) | Age > 55 Y (n = 158) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 149) | Female (n = 106) | P-value | Male (n = 81) | Female (n = 77) | P-value | ||

| White blood cell (×109/L) | 3.5–9.5 | 7.77 (6.77, 10.2) | 7.45 (6.55, 9.10) | 0.341 | 7.98 (6.76, 11.1) | 7.76 (6.71, 9.51) | 0.346 |

| Neutrophil (×109/L) | 1.8–6.3 | 5.93 (4.95, 7.90) | 5.89 (4.65, 8.03) | 0.713 | 6.27 (4.87, 8.45) | 6.00 (4.68, 8.60) | 0.464 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/L) | 1.1–3.2 | 1.35 (1.07, 1.77) | 1.45 (1.13, 1.74) | 0.532 | 1.13 (0.84, 1.40) | 1.31 (1.10, 1.67) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 316–354 | 135 (128, 141) | 117 (108, 124) | <0.001 | 126 (115, 135) | 116 (108, 124) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 125–350 | 274 (225, 349) | 262 (234, 311) | 0.536 | 240 (216, 286) | 268 (232, 314) | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (μg/ml) | 0–1.5 | 0.56 (0.31, 1.15) | 0.62 (0.33, 1.17) | 0.720 | 1.11 (0.68, 4.15) | 1.25 (0.58, 3.85) | 0.803 |

| ALT (U/L) | 9–50 | 37.0 (25.0, 55.0) | 22.0 (14.3, 37.5) | <0.001 | 33.0 (19.5, 51.5) | 22.0 (15.0, 35.0) | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/L) | 120–250 | 331 (284, 397) | 327 (281, 404) | 0.941 | 356 (290, 479) | 338 (278, 429) | 0.041 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 0–7 | 7.92 (5.81, 10.5) | 7.77 (6.20, 10.7) | 0.466 | 8.93 (6.31, 12.9) | 8.91 (6.73, 13.2) | 0.616 |

| Prealbumin (mg/L) | 200–430 | 151 (117, 215) | 137 (92.5, 194) | 0.079 | 89.0 (56.8, 129) | 109 (79.0, 155) | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40–55 | 30.0 (26.8, 33.7) | 30.9 (27.0, 35.4) | 0.107 | 30.3 (27.0, 33.8) | 30.4 (27.4, 33.9) | 0.795 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0–26 | 11.8 (8.83, 18.4) | 11.3 (8.90, 14.9) | 0.553 | 12.1 (9.63, 15.4) | 12.2 (9.38, 16.1) | 0.735 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 57–97 | 75.9 (68.8, 84.9) | 54.2 (50.2, 61.1) | <0.001 | 81.2 (68.3, 99.2) | 60.0 (52.2, 69.2) | <0.001 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 0–190 | 92.5 (58.5, 168) | 51.0 (38.3, 84.0) | <0.001 | 103 (67.0, 174) | 60.0 (39.0, 117) | <0.001 |

| CK-MB (U/L) | 0–24 | 15.0 (11.0, 18.0) | 12.0 (9.50, 16.0) | 0.005 | 15.0 (12.0, 19.0) | 13.0 (10.0, 16.0) | 0.002 |

| HS-CRP (mg/L) | 0–3 | 26.7 (11.88, 82.4) | 12.9 (3.90, 39.3) | <0.001 | 93.6 (44.3, 131) | 26.0 (10.1, 63.9) | <0.001 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0–0.05 | 0.05 (0.05, 0.09) | 0.05 (0.05, 0.05) | <0.001 | 0.07 (0.05, 0.23) | 0.05 (0.05, 0.10) | 0.001 |

| Troponin (pg/ml) | 0–28 | 4.70 (1.78, 14.3) | 4.10 (1.80, 13.1) | 0.968 | 6.95 (2.25, 17.5) | 5.80 (2.25, 17.4) | 0.979 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.3–5.2 | 3.62 (3.15, 4.17) | 3.64 (3.11, 4.21) | 0.883 | 3.42 (2.93, 4.00) | 3.88 (3.38, 4.46) | <0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.29–1.55 | 0.85 (0.71, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.19) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.70, 1.04) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.21) | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.1–3.37 | 2.32 (1.82, 2.66) | 2.01 (1.58, 2.46) | 0.028 | 1.85 (1.52, 2.35) | 2.13 (1.67, 2.64) | 0.016 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.51–1.70 | 1.73 (1.54, 2.15) | 1.78 (1.59, 2.19) | 0.444 | 1.65 (1.45, 1.99) | 1.77 (1.52, 2.15) | 0.024 |

| ESR (mm/H) | 0–15 | 46.7 (35.3, 61.5) | 49.5 (29.2, 61.9) | 0.725 | 53.5 (28.1, 63.0) | 58.6 (43.5, 72.2) | 0.065 |

Data are median (IQR). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ALT, alanine amino transferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IL-6, interleukin-6; CK-MB, creatine kinase isoenzyme-MB; HS-CRP, high sensitive c reaction protein; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglyceride; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Bold value means P < 0.05.

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this is the first multicentre retrospective cohort study to analyze the sex and estrogen effect on the clinical characteristics and outcomes in adult patients with SARS-COV-2 infection, and the role of estrogen in COVID-19 development. Estrogen modulates immune function in females and may contribute to resistance against infection, while estrogen level is significant difference before and after menopause. To explore the beneficial effect of estrogen in female COVID-19 patients, we made the subgroup comparison according to the age of menopause in women. We documented that fever was more common in men cases, while digestive symptoms were less common. Men with COVID-19 were more prone to develop into the severe condition and die. The same trend was also found in Europe (31). Although no difference in-hospital mortality was noted in women under 55 compared with the same age men, there was significantly difference in women over 55 with men of the same age group, which may be associated with a lower inflammatory response in premenopausal women. However, differences in mortality between premenopausal and postmenopausal women was not significant, suggesting that female mortality in COVID-19 was lower than male might not be directly related to the effect of estrogen. Experimental data showed that male sex was an independent risk factor associated with refractory disease and death (12, 32, 33). We also found that gender-related lifestyle, more chronic diseases, lower lymphocytes on admission, more complications and dyslipidemia may result in higher mortality rate in older men than in older women. These findings contribute to the discussion of whether older male patients with SARS-COV-2 infection should be paid more attention.

It has been known that males and females differ in their susceptibility and response to viral infections, resulting in sex differences in incidence and disease severity (18, 34). The reduced susceptibility of females to viral infections could be attributed to the protection from X chromosome and sex hormones, which play an essential role in innate and adaptive immunity (35). SARS-CoV-2 uses ACE2 on pulmonary endothelium as an entry receptor, while the gene for the ACE2 is on the X chromosome (36), which may be the reason for the higher prevalence of COVID-19 in men than in women. In addition, in premenopausal women, estradiol produced by the ovary, is the estrogen in largest quantity (40–400 pg/mL) and most potent. Nevertheless, ovary almost stops producing estradiol after menopause, leading to estradiol level is significant reduced in postmenopausal women (<20 pg/mL), and no difference with men. In our study, the inflammatory marker HS-CRP was lowest in premenopausal women, while HS-CRP may result in cytokine storms and relate to disease severity and mortality (2, 6). Previous study showed hypopituitary women had decreased level of estrogen and increased level of CRP (37). Therefore, the lower morbidity and mortality of premenopausal women may be related to estrogen-mediated low inflammatory response. We also found that no difference in mortality among premenopausal and postmenopausal women. This suggested estrogen influenced the infection with SARS-COV-2 and pathogenesis of COVID-19, but might not be directly related to the lower mortality in women. However, our study had the small sample size, and the majority of younger patients are being non-severe COVID-19 condition and fewer died. Further investigation with larger –scale data is needed to assess the influence of estrogen on COVID-19 patients.

Although advancing age is associated with greater risk of death in both sexes, the male bias remains evident (15). Our study suggested that age, male sex and comorbidities were independently associated with in-hospital mortality, as well as sex and age had significant interaction for in-hospital mortality of COVID-19. The age-related sex differences in patients with COVID-19 were consistent with reported cases of seasonal and pandemic influenza A virus infections in Australia and Japan (38, 39). In the present study, we found the increasing mortality might be associated with higher rates of smoking, hypertension and complications in older men. Smoking rate is higher among men than women worldwide (40), consisting with the result in this study. Such behavior is associated with the risk of developing comorbidities. Simultaneously, smoking is related to higher expression of ACE2 and may be a risk facto rfor disease prevalence and severity (4, 40, 41), but no firm conclusions can be drawn. Hypertension was the most common chronic diseases, particularly in older male patients. Previous epidemiological data indicated an association between hypertension and severe disease or death from COVID-19 (7–9). Besides, the incidence of ARDS and other complications were higher in older men with COVID-19, especially acute liver injury and acute cardiac injury, which might also affect disease severity and prognosis.

In the older group, total lymphocyte count was significantly lower in men than in women. Lymphocytes play a decisive role in maintaining immune homeostasis and inflammatory response throughout the body. Previous studies had suggested that severe COVID-19 patients might have lymphocyte responses. A meta-analysis reported lymphopenia had a 3-fold higher risk of developing severe COVID-19, and lower lymphocyte counts was an effective biomarker in predicting the severity and prognosis in COVID-19 patients (42). Therefore, lymphopenia may be one potential mechanism of age-related sex differences.

In this study, dyslipidemia was found in older patients infected with SARS-COV-2. The TC, HDL, LDL, and TG levels in older male patients showed markedly decreases as compared to older female patients. This goes along well with previously data, that the LDL, HDL and TC levels in COVID-19 patients showed significant decreases at the time on admission (43). Lipids play a central role in viral infection, as they represent the structural foundations of cellular and viral membranes, while LDL levels inversely correlated to disease severities, which could be a predictor for disease progress and poor prognosis (43). The exact mechanisms of dyslipidemia in COVID-19 patients have remained unclear; however, there were several potential causes. Firstly, circulating lipid became oxidized in the inflammatory conditions, which resulted in the loss their protective functions and contributed to ongoing inflammation (44). Meanwhile, inflammation regulated lipoprotein metabolism indirectly via the cytokines, such as resulting in reduced expression and secretion of apoprotein of HDL, remodeling HDL-associated proteome, and promote HDL clearance from plasma (45, 46). Therefore, the measurement of the oxidized LDL and apoprotein of HDL can confirm these notions. Secondly, hepatocytes are the dominant cell type determining systemic LDL levels, and liver injury which is a common complication in older men, can affect the serum LDL levels. Thirdly, older male patients may have exacerbated inflammatory response, while systemic inflammation may accelerate clearance of LDL, which may partly explain the reduction in circulating LDL. Finally, estrogen levels in postmenopausal women affect the normal levels of blood lipids, which lead to increase TC, TG and LDL levels.

Limitation

There are several limitations in this study. Firstly, it was a retrospective multicentre study, and there were probably a significant referral bias, recall bias and measurement bias. Besides, this is an observational study and its results are subject to unobserved confounding factors. Secondly, we did not measure estrogen level and collect the history of hormone replacement therapy. However, we refer to previous studies and perform the subgroup analysis based on the age of menopause, to investigate the effect of estrogen in morbidity and mortality in patients with COVID-19 for the first time. Thirdly, only the indexes on admission were selected for analysis, without dynamic monitoring. Further, large-scale clinical studies and basic research are needed to explore risk factors for individualized assessment. Finally, no power calculation was made for the study, so the study is an exploratory study and its results are subject to false positive error and should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, older age, male sex and comorbidities were independently associated with in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 patients. Moreover, sex and age are interactively associated with outcome of COVID-19. Although female mortality in COVID-19 is lower than male in this study, it might not be directly related to the effect of estrogen. Further study is warranted to identify the sex difference in COVID-19 and mechanisms involved.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Jinan Infectious diseases Hospital, Shandong Provincial Chest Hospital, and Huanggang Central Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YC and MM were involved in study concept and design and revised the final manuscript. JS, GQ, WS, CW, ZZ, XW, and XB collected the epidemiological and clinical data. PW, QY, and JJ processed statistical data. JS and GQ drafted the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81200238), and the Key Research and Development Projects of Shandong Province (2019GSF108059).

References

- 1.WHO Main Website. Available online at: https://www.who.int (accessed June 17, 2020).

- 2.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao Y, Tian Y, Zhou J, Ma X, Yang M, Wang S. Epidemiological characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Shaanxi, China by 8 February 2020. Eur Respir J. (2020) 55:2000310. 10.1183/13993003.00310-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan W, Liang W, Zhao Y, Liang H, Chen Z, Li Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. (2020) 55:2000547. 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:846–8. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:934–43. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow N, Fleming-Dutra K, Gierke R, Hall A, Hughes M, Pilishvili T, et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:382–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo H, Liu S, Wang Y, Phillips-Howard PA, Ju S, Yang Y, et al. Age differences in clinical features and outcomes in patients with COVID-19, Jiangsu, China: a retrospective, multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e39887. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Castelnuovo A, Bonaccio M, Costanzo S, Gialluisi A, Antinori A, Berselli N, et al. Common cardiovascular risk factors and in-hospital mortality in 3,894 patients with COVID-19: survival analysis and machine learning-based findings from the multicentre Italian CORIST study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2020) 30:1899–913. 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.07.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. (2020) 395:507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. (2020) 323:1574. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haitao T, Vermunt JV, Abeykoon J, Ghamrawi R, Gunaratne M, Jayachandran M, et al. COVID-19 and sex differences: mechanisms and biomarkers. Mayo Clin Proc. (2020) 95:2189–203. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:442–7. 10.1038/s41577-020-0348-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlberg J, Chong DS, Lai WY. Do men have a higher case fatality rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome than women do? Am J Epidemiol. (2004) 159:229–31. 10.1093/aje/kwh056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alghamdi I, Hussain I, Alghamdi M, Almalki S, Alghamdi M, Elsheemy M. The pattern of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive epidemiological analysis of data from the Saudi Ministry of Health. Int J Gen Med. 7:417–23. 10.2147/IJGM.S67061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:626–38. 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein SL. The effects of hormones on sex differences in infection: from genes to behavior. Neurosci Biobehav R. (2000) 24:627–38. 10.1016/S0149-7634(00)00027-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson DP, Huber SA, Moussawi M, Roberts B, Teuscher C, Watkins R, et al. Sex chromosome complement contributes to sex differences in coxsackievirus B3 but not influenza A virus pathogenesis. Biol Sex Differ. (2011) 2:8. 10.1186/2042-6410-2-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev. (2007) 28:521–74. 10.1210/er.2007-0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Channappanavar R, Fett C, Mack M, Ten Eyck PP, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Immunol. (2017) 198:4046–53. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Interim Guidance for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Implementation of Revised Fifth Edition). National Health and Health Commission (2020). Available online at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/d4b895337e19445f8d728fcaf1e3e13a.shtml (accessed May 8, 2020).

- 24.Ning NG, Yun WX, Yan YH. The research on the factors affecting the timing of natural menopause in Chinese city women. Maternal Child Health Care China. (2011) 26:1191–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis M, Diamond J, Montgomery D, Krishnan S, Eagle K, Jackson E. Acute coronary syndrome in young women under 55 years of age: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol. (2015) 104:648–55. 10.1007/s00392-015-0827-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2019) 200:e45–67. 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. (2016) 315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. (2012) 120:c179–84. 10.1159/000339789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. (2012) 307:2526–33. 10.1001/jama.2012.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. (2020) 395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. (2020) 11:29. 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, Deng L, Zhao Q, Wang H, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 16:ciaa270. 10.1093/cid/ciaa270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Wang X, Jia X, Li J, Hu K, Chen G, et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26:767–72. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markle JG, Fish EN. SeXX matters in immunity. Trends Immunol. (2014) 35:97–104. 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaillon S, Berthenet K, Garlanda C. Sexual dimorphism in innate immunity. Clin Rev Allerg Immu. (2019) 56:308–21. 10.1007/s12016-017-8648-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel SK, Velkoska E, Freeman M, Wai B, Lancefield TF, Burrell LM. From gene to protein—experimental and clinical studies of ACE2 in blood pressure control and arterial hypertension. Front Physiol. (2014) 5:227. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sesmilo G, Miller KK, Hayden D, Klibanski A. Inflammatory cardiovascular risk markers in women with hypopituitarism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:5774–81. 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eshima N, Tokumaru O, Hara S, Bacal K, Korematsu S, Tabata M, et al. Sex- and age-related differences in morbidity rates of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus of swine origin in Japan. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e19409. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong KC, Luscombe GM, Hawke C. Influenza infections in Australia 2009–2015: is there a combined effect of age and sex on susceptibility to virus subtypes? BMC Infect Dis. (2019) 19:42. 10.1186/s12879-019-3681-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai H. Sex difference and smoking predisposition in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:e20. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30117-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walter LA, McGregor AJ. Sex- and gender-specific observations and implications for COVID-19. West J Emerg Med. (2020) 21:507–9. 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, Wu Y, Huang J, Deng Y, et al. Lymphopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 96:131–5. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan J, Wang H, Ye G, Cao X, Xu X, Tan W, et al. Letter to the editor: low-density lipoprotein is a potential predictor of poor prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Metab Clin Exp. (2020) 107:154243. 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guirgis FW, Dodani S, Moldawer L, Leeuwenburgh C, Bowman J, Kalynych C, et al. Exploring the predictive ability of dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein for adverse outcomes in emergency department patients with sepsis. Shock. (2017) 48:539–44. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Westhuyzen DR, de Beer FC, Webb NR. HDL cholesterol transport during inflammation. Curr Opin Lipidol. (2007) 18:147–51. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328051b4fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGillicuddy FC, de la Llera Moya M, Hinkle CC, Joshi MR, Chiquoine EH, Billheimer JT, et al. Inflammation impairs reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. Circulation. (2009) 119:1135–45. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.810721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.