Abstract

Objectives:

To establish whether clinicopathologic and genomic characteristics may explain the poor prognosis associated with advanced age in ER+/HER2− breast cancer.

Materials and Methods:

The cohort included 271 consecutive post-menopausal patients with ER+/HER2− invasive breast cancer ages 55 years and older. Patients were categorized as “younger” (ages 55- < 75) and “older” (ages ≥75). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate locoregional recurrence (LRR), recurrence-free interval (RFi), and overall survival (OS). Gene expression of tumor samples was assessed with Affymetrix Rosetta/Merck Human RSTA microarray platform. Differential gene expression analysis of tumor samples was performed using R package Limma.

Results:

271 breast cancer patients were identified, including 186 younger and 85 older patients. Older patients had higher rates of Luminal B subtype (53% vs 34%) and lower rates of Luminal A subtype (42% vs 58%, p = 0.02). Older patients were less likely to receive chemotherapy (9% vs 40%, p < 0.001) and hormone therapy (71% vs 89%, p < 0.001). For cases of grade 1–2 disease, older patients had a higher proportion of the luminal B subtype (49% vs. 30%, p = 0.014). Age ≥ 75 predicted for inferior OS (HR = 3.06, p < 0.001). The luminal B subtype predicted for inferior OS (HR = 2.12, p = 0.014), RFi (HR 5.02, p < 0.001), and LRR (HR = 3.12, p = 0.045). There were no significant differences in individual gene expression between the two groups.

Conclusion:

Women with ER+/HER2− breast cancer ≥75 years old had higher rates of the more aggressive luminal B subtype and inferior outcomes. Genomic testing of these patients should be strongly considered, and treatment should be intensified when appropriate.

Keywords: Elderly, Breast cancer, PAM50, Gene expression, Luminal B, Luminal A

1. Introduction

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer amongst women, and age is the most significant risk factor [1]. Breast cancer in older patients is therefore a growing challenge, as the older population within the United States continues to expand. Treatment of these patients is often complicated, as they may be less fit for standard treatment options. In addition, there is no clear consensus on the treatment of breast cancer within older patients, as they are often underrepresented in clinical trials [2,3]. In fact, the recent TAILORx and MINDACT trials, which identified patients that could be safely spared chemotherapy based upon genomic risk, failed to include patients over 75 years old [4,5]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that older patients that are included in clinical trials have fewer comorbid conditions, higher socioeconomic status, and smaller tumors, and therefore, do not represent patients of corresponding age from the general population [6].

Older patients with breast cancer are more likely to have estrogen receptor (ER)- and progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2)-negative tumors, which are generally associated with improved outcomes [7-9]. However, the prognosis of ER + breast cancer in postmenopausal women worsens with age [10,11]. It has been postulated that these inferior outcomes could be secondary to increased patient comorbidities, more frequent presentation with advanced stage [9,12], unique genomic aberrations [13], and undertreatment [14,15]. However, there remains limited evidence to explain the inferior outcomes observed in older patients with breast cancer. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether clinicopathologic or genomic characteristics may explain the poorer prognosis associated with age amongst ER+, HER2− postmenopausal patients with breast cancer.

2. Method and Materials

2.1. Patient Selection and Clinical Risk Determination

The study population included 271 consecutive patients with invasive breast cancer diagnosed from November 1997 to August 2010 that were identified from a prospective tissue collection database with available receptor status and genomic profiling from one academic and two community hospitals. Inclusion criteria for patient querying included postmenopausal women age 55 and older with primary, ER-positive, HER2-negative invasive breast carcinoma who did not receive chemotherapy prior to sample collection. There were no cases of bilateral or multifocal tumors. This study met the approval of the institutional review board. Clinical and pathological data were collected via retrospective chart review. We used Adjuvant! Online (version 8.0 with HER2 status) (www.adjuvantonline.com) to determine clinical risk, as used by the MINDACT trial [5]. This prognostic tool utilizes grade, nodal status, and tumor size to stratify patients into high versus low clinical risk.

2.2. Gene Expression Subtyping and Genomic Profiling

Tumor samples were assayed using the custom Rosetta/Merck HuRSTA_2a520709 Affymetrix gene expression microarray platform (GEO: GPL15048). CEL files were normalized against the median CEL file using iterative rank-order normalization (IRON) [16]. Principle component analysis of all samples showed that RNA quality, as measured by RNA integrity number (RIN) value, dominated the first principle component. A partial least squares (PLS) model was trained upon the fresh frozen samples for which RIN was available, used to re-estimate the RNA quality of all samples, then its first principle component removed to correct the signals for RNA quality. As the Affymetrix chips have multiple probesets for some genes, where possible analysis was completed at the probeset level. The gene expression subtypes were determined via the 50-gene signature classifier, PAM50, as previously established by Perou et al. [17] using the Bioconductor package genefu [18] where the median expression level was used in settings where multiple probesets mapped to the same gene.

2.3. Gene Expression Association Analysis

The Cox proportional-hazards model was utilized at the probeset level to examine the association of each gene expression with time to locoregional recurrence (LRR). P-values were adjusted using the q-value method for multiple comparisons. Q-values less than 0.05 were considered statistical significant. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with the Limma package in R. To investigate biologic themes associated with genes significantly correlated with age subgroups (younger vs older) and LRR, gene set enrichment analysis was performed with the Enrich R tool (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) [19,20].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Patient and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics including median and range for continuous measures, and proportions and frequencies for categorical measures. The association between continuous variables and age class (younger vs older patients) were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis tests, and the associations of categorical variables were evaluated using Chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. Primary outcomes were measured from the date of pathologic diagnosis and included overall survival (OS, event defined as death from any cause), time to LRR (event defined as local or regional relapse), and recurrence-free interval (RFi, event defined as local, regional, or distant disease relapse). Time-to-event estimation was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method with all observations right-censored after 10 years. Cox proportional-hazards models were used identify clinical and genomic features associated with clinical time-to-event outcomes with all observations past 10 years censored. Variables with p < 0.05 were included in the multivariable survival analysis. Statistical analyses were completed using R.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Two hundred seventy-one postmenopausal patients met the inclusion criteria and were grouped into “younger” patients (age 55- < 75 years) and “older” patients (≥75 years) (Table 1). Older patients had lower rates of the Luminal A subtype (42.4% vs 58.1%) and higher rates of Luminal B subtype (52.9% vs 34.4%) when compared to younger patients (p = 0.020). Older patients were significantly less likely to receive chemotherapy (9.4% vs 40.3%, p < 0.001) and hormone therapy (71% vs 89%, p < 0.001). In comparison to the luminal A subtype, patients with the luminal B subtype were more frequently grade 3 (33.0% vs 9.8%, p < 0.001) and higher clinical risk by Adjuvant! Online (48.6% vs 30.3%, p = 0.0046).

Table 1.

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics.

| Overall | Age 55- < 75 | Age ≥ 75 | P | Luminal A | Luminal B | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N = 271 | N = 186 | N = 85 | N = 144 | N = 109 | ||

| Race | 0.335 | 0.736 | |||||

| White | 255 (94.4%) | 173 (93.5%) | 82 (96.5%) | 137 (95.1%) | 102 (93.6%) | ||

| AA | 5 (1.9%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (2.4%) | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1.8%) | ||

| Hispanic, Asian, & Other | 10 (3.7%) | 9 (4.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | 5 (3.5%) | 5 (1.2%) | ||

| Predominant histology | 0.107 | 0.298 | |||||

| IDC | 202 (74.5%) | 136 (73.1%) | 66 (77.6%) | 103 (71.5%) | 87 (79.8%) | ||

| ILC | 41 (15.1%) | 26 (14.0%) | 15 (17.6%) | 24 (16.7%) | 14 (12.8%) | ||

| Other | 28 (10.3%) | 24 (12.9%) | 4 (4.7%) | 17 (11.8%) | 8 (7.3%) | ||

| pTNM | 0.224 | 0.392 | |||||

| 1 | 120 (45.3%) | 89 (48.6%) | 31 (37.8%) | 67 (47.9%) | 42 (39.3%) | ||

| 2 | 107 (40.4%) | 68 (37.2%) | 39 (47.6%) | 54 (38.6%) | 47 (43.9%) | ||

| 3 | 38 (14.3%) | 26 (14.2%) | 12 (14.6%) | 19 (13.6%) | 18 (16.8%) | ||

| Grade | 0.293 | <0.001 | |||||

| 1 | 61 (22.6%) | 41 (22.2%) | 20 (23.5%) | 35 (24.3%) | 15 (13.8%) | ||

| 2 | 156 (57.8%) | 112 (60.5%) | 44 (51.8%) | 94 (65.3%) | 58 (53.2%) | ||

| 3 | 53 (19.6%) | 32 (17.3%) | 21 (24.7%) | 15 (10.4%) | 36 (33.0%) | ||

| LVSI | 0.185 | 0.483 | |||||

| No | 189 (70.0%) | 129 (69.7%) | 60 (70.6%) | 99 (68.8%) | 76 (70.4%) | ||

| Yes | 53 (19.6%) | 33 (17.8%) | 20 (23.5%) | 28 (19.4%) | 24 (22.2%) | ||

| Unknown | 28 (10.4%) | 23 (12.4%) | 5 (5.9%) | 17 (11.8%) | 8 (7.4%) | ||

| Molecular subtype (PAM50) | 0.020 | ||||||

| Basal | 6 (2.2%) | 4 (2.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | ||||

| Her2 | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||||

| Luminal B | 109 (40.2%) | 64 (34.4%) | 45 (52.9%) | ||||

| Luminal A | 144 (53.1%) | 108 (58.1%) | 36 (42.4%) | ||||

| Normal | 10 (3.7%) | 9 (4.8%) | 1 (1.2%) | ||||

| Clinical Risk (via Adjuvant! Online) | 0.317 | 0.017 | |||||

| High | 107 (39.5%) | 71 (38.2%) | 36 (42.4%) | 50 (34.7%) | 53 (48.6%) | ||

| Low | 113 (41.7%) | 83 (44.6%) | 30 (35.3%) | 69 (47.9%) | 33 (30.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 51 (18.8%) | 32 (17.2%) | 19 (22.4%) | 25 (17.4%) | 23 (21.1%) | ||

| Hormone therapy | <0.001 | 0.211 | |||||

| No | 39 (14.4%) | 16 (8.6%) | 23 (27.1%) | 18 (12.5%) | 20 (18.4%) | ||

| Yes | 225 (83.0%) | 165 (88.7%) | 60 (70.6%) | 121 (84.0%) | 88 (80.7%) | ||

| Unknown | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (2.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (3.5%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | <0.001 | 0.514 | |||||

| No | 180 (66.4%) | 105 (56.5%) | 75 (88.2%) | 97 (67.4%) | 69 (63.3%) | ||

| Yes | 83 (30.6%) | 75 (40.3%) | 8 (9.4%) | 42 (29.2%) | 38 (34.9%) | ||

| Unknown | 8 (3.0%) | 6 (3.2%) | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (3.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | ||

| Local treatment | 0.989 | 0.813 | |||||

| Mastectomy alone | 87 (32.1%) | 60 (32.3%) | 27 (31.8%) | 48 (33.3%) | 35 (32.1%) | ||

| Mastectomy and PMRT | 36 (13.3%) | 24 (12.9%) | 12 (14.1%) | 17 (11.8%) | 16 (14.7%) | ||

| Lumpectomy and BCT | 141 (52.0%) | 97 (52.2%) | 44 (51.8%) | 74 (51.4%) | 56 (51.4%) | ||

| Unknown | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (2.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (3.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | ||

| XRT | 0.931 | 0.779 | |||||

| No | 94 (34.7%) | 63 (33.9%) | 31 (36.5%) | 52 (36.1%) | 38 (34.9%) | ||

| Yes | 170 (63.1%) | 118 (63.4%) | 52 (61.2%) | 87 (60.4%) | 69 (63.3%) | ||

| Unknown | 7 (2.6%) | 5 (2.7%) | 2 (2.4%) | 5 (3.5%) | 2 (1.8%) | ||

| Boost XRT | 0.941 | 0.425 | |||||

| No | 81 (46.0%) | 56 (46.3%) | 25 (45.5%) | 45 (49.5%) | 30 (42.3%) | ||

| Yes | 80 (45.5%) | 54 (44.6%) | 26 (47.3%) | 37 (40.7%) | 36 (50.7%) | ||

| Unknown | 15 (8.5%) | 11 (9.1%) | 4 (7.3%) | 9 (9.9%) | 5 (7.0%) |

Abbreviations: AA = African American, IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma, pTNM = pathologic tumor-node-metastasis stage, XRT = external beam radiotherapy, PMRT = post-mastectomy radiation treatment, BCT = breast conserving treatment, LVSI = lymphovascular space invasion, prolif = proliferation.

Statistically significant values are in bold

Of those patients with grade 1–2 disease, older patients had a higher proportion of the luminal B subtype (49.2% vs 30.2%, p = 0.014) (Table 2). Of those deemed low clinical risk (via Adjuvant! Online), older patients had a significantly higher percentage of the luminal B subtype (50% vs 25%, p = 0.026) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grade, clinical risk (via Adjuvant! Online), and molecular subtype by age.

| Luminal A | Luminal B | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1/2 | Age 55- < 75 | 97 (69.8%) | 42 (30.2%) | 0.014 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 32 (50.8%) | 31 (49.2%) | ||

| Low Clinical Risk | Age 55- < 75 | 54 (75.0%) | 18 (25.0%) | 0.026 |

| Age ≥ 75 | 15 (50.0%) | 15 (50.0%) |

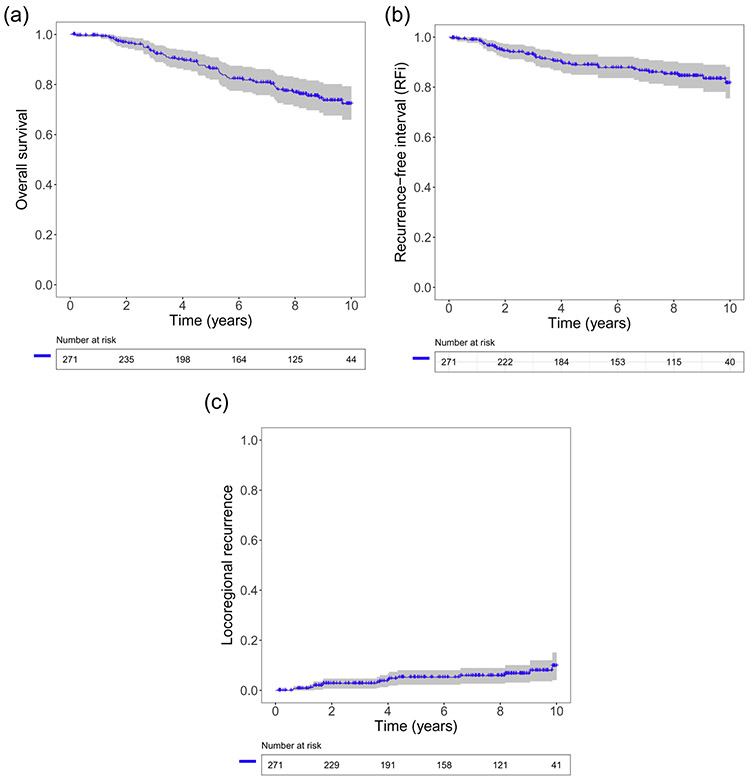

3.2. Clinical Outcomes and Association with Gene Expression

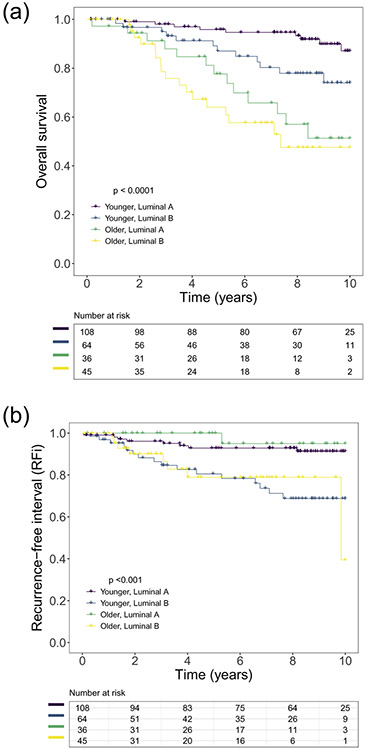

The median follow-up time for OS was 90.9 months (range: 1.4–-185 months). The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year OS rates were 97%, 86%, and 72%, respectively (Fig. 1A). The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year RFi rates were 94%, 89%, and 82%, respectively (Fig. 1B). The 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year LRR were 2.8%, 5.3%, and 10.1%, respectively (Fig. 1C). The median OS for younger patients with the luminal A subtype and older patients with the luminal B subtype were 151 months and 88 months, respectively (Fig. 2A). The median RFi for younger patients with the luminal A subtype and older patients with the luminal B subtype were 183 months and 118 months, respectively (Fig. 2B). The median OS and median RFi for younger patients with the luminal B subtype and older patients with the luminal A subtype were not reached.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) overall survival, (B) recurrence-free interval, and (C) loco-regional recurrence for post-menopausal patients with estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor 2 negative breast cancer.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve depicting (A) overall survival and (B) recurrence-free interval for post-menopausal patients with estrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor 2 negative breast cancer, comparing younger (age 55 to <75 years) luminal A patients (purple), younger luminal B patients (blue), older (age ≥ 75 years) luminal A patients (green), and older luminal B patients (yellow).

Using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, the following variables were found to be associated with OS: advanced stage, age ≥ 75 years (HR = 3.06, 95% CI 1.71–5.47, p ≤0.001), and Luminal B subtype (HR = 2.12, 95% CI 1.18–3.81, p = 0.014) (Table 3, Fig. 2A). The Luminal B subtype (HR 5.02, 95% CI 2.22–11.4, p < 0.001) was associated with inferior RFi (Table 4, Fig. 2B). Finally, non-white race (HR 8.18, 95% CI 2.17–30.83, p = 0.002) and Luminal B subtype (HR 3.12, 95% CI 1.03–9.47) predicted for inferior LRR (Table 5). The receipt of hormone therapy was associated with improved OS (HR 0.31, p = 0.001), RFi (HR 0.22, p = 0.001), and LRR (HR 0.12, p ≤0.001). No individual genes (probesets) were found to be differentially expressed between the younger and older patients or associated with time to LRR (q-values >0.05).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for OS.

| UVA |

MVA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 4.84 (2.80–8.36) | <0.001 | 3.06 (1.71–5.47) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||

| White (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| AA, Hispanic, Asian, & Other | 3.32 (1.41–7.79) | 0.006 | 2.368 (0.169–1.288) | 0.085 |

| Predominant histology | ||||

| IDC (Reference) | 1 | |||

| ILC | 0.55 (0.22–1.38) | 0.201 | ||

| Others | 0.91 (0.36–2.30) | 0.843 | ||

| pTNM | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2.75 (1.44–5.26) | 0.002 | 2.55 (1.31–4.97) | 0.006 |

| 3 | 3.76 (1.73–8.14) | <0.001 | 3.66 (1.58–8.49) | 0.002 |

| XRT | 0.93 (0.53–1.64) | 0.804 | ||

| Primary treatment | ||||

| Mastectomy (Reference) | 1 | |||

| PMRT | 1.31 (0.56–3.10) | 0.535 | ||

| Lumpectomy and BCT | 1.12 (0.609–2.07) | 0.730 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | |||

| 2 | 0.57 (0.30–1.07) | 0.082 | ||

| 3 | 1.14 (0.56–2.31) | 0.712 | ||

| LVSI | 1.14 (0.58–2.24) | 0.699 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 0.27 (0.15–0.50) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.15–0.62) | 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.70 (0.38–1.29) | 0.258 | ||

| Molecular subtype (PAM50) | ||||

| Basal | 2.45 (0.58–10.44) | 0.225 | 2.57 (0.58–11.43) | 0.216 |

| Her2 | 3.65 (0.49–27.14) | 0.206 | 2.60 (0.29–23.51) | 0.396 |

| Luminal B | 2.21 (1.27–3.85) | 0.005 | 2.11 (1.17–3.81) | 0.014 |

| Luminal A (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Normal | 0.68 (0.09–5.06) | 0.708 | 1.38 (0.18–10.52) | 0.756 |

| High Clinical Risk (via Adjuvant! Online) | 1.84 (0.97–3.50) | 0.061 | ||

Abbreviations: OS = overall survival, UVA = univariate analysis, MVA = multivariate analysis, HR = hazard ratio, AA = African American, IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma, pTNM = pathologic tumor-node-metastasis stage, XRT = external radiotherapy, PMRT = post-mastectomy radiation treatment, BCT = breast conserving treatment, LVSI = lymphovascular space invasion.

Statistically significant values are in bold

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for RLPFS.

| UVA |

MVA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 1.12 (0.54–2.35) | 0.761 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| AA, Hispanic, Asian, & Other | 4.60 (1.77–11.95) | 0.002 | 2.80 (0.84–9.31) | 0.093 |

| Predominant histology | ||||

| IDC (Reference) | 1 | |||

| ILC | 1.63 (0.73–3.61) | 0.229 | ||

| Others | 0.66 (0.16–2.77) | 0.567 | ||

| pTNM | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 2.46 (1.13–5.35) | 0.023 | 1.90 (0.84–4.31) | 0.126 |

| 3 | 2.88 (1.09–7.57) | 0.032 | 2.02 (0.64–6.45) | 0.233 |

| XRT | 0.41 (0.21–0.80) | 0.009 | 0.70 (0.08–5.95) | 0.741 |

| Primary treatment | ||||

| Mastectomy (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| PMRT | 0.69 (0.26–1.88) | 0.473 | 0.95 (0.09–10.2) | 0.966 |

| Lumpectomy and BCT | 0.37 (0.18–0.78) | 0.009 | 0.53 (0.06–4.52) | 0.563 |

| Grade | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | |||

| 2 | 0.10 (0.46–2.60) | 0.829 | ||

| 3 | 1.34(0.49–3.71) | 0.568 | ||

| LVSI | 1.48 (0.65–3.34) | 0.348 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 0.33 (0.15–0.74) | 0.007 | 0.22 (0.09–0.56) | 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 1.26 (0.63–2.52) | 0.513 | ||

| Molecular subtype (PAM50) | ||||

| Basal | 3.10 (0.39–24.5) | 0.284 | 6.33 (0.74–54.1) | 0.092 |

| Her2 | – | – | – | – |

| Luminal B | 4.45 (2.06–9.59) | <0.001 | 5.02 (2.22–11.4) | <0.001 |

| Luminal A (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Normal | 1.64 (0.21–12.9) | 0.640 | 2.79 (0.33–23.4) | 0.346 |

| High Clinical Risk (via Adjuvant! Online) | 1.88 (0.88–4.02) | 0.104 | ||

Abbreviations: RLPFS = relapse free survival, UVA = univariate analysis, MVA = multivariate analysis, HR = hazard ratio, AA = African American, IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma, pTNM = pathologic tumor-node-metastasis stage, XRT = external radiotherapy, PMRT = post-mastectomy radiation treatment, BCT = breast conserving treatment, LVSI = lymphovascular space invasion.

Statistically significant values are in bold

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for LRR.

| UVA |

MVA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 0.96 (0.30–3.01) | 0.939 | ||

| Race | ||||

| White (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| AA, Hispanic, Asian, & Other | 7.08 (1.96–25.52) | 0.003 | 8.18 (2.17–30.83) | 0.002 |

| Predominant histology | ||||

| IDC (Reference) | 1 | |||

| ILC | 2.54 (0.87–7.44) | 0.089 | ||

| Others | 0.80 (0.10–6.28) | 0.835 | ||

| pTNM | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1.38 (0.48–3.95) | 0.553 | ||

| 3 | 1.20 (0.192–5.78) | 0.824 | ||

| XRT | 0.42 (0.15–1.15) | 0.092 | ||

| Primary treatment | ||||

| Mastectomy (Reference) | 1 | |||

| PMRT | – | – | ||

| Lumpectomy and BCT | 0.63 (0.23–1.75) | 0.379 | ||

| Grade | ||||

| 1 (Reference) | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1.31 (0.36–4.78) | 0.679 | ||

| 3 | 1.20 (0.24–5.94) | 0.825 | ||

| LVSI | 1.48 (0.39–5.58) | 0.563 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 0.16 (0.06–0.44) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.04–0.37) | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.73 (0.23–2.29) | 0.589 | ||

| Molecular subtype (PAM50) | ||||

| Basal | – | – | 0.00 (0.00, Inf) | 0.998 |

| Her2 | – | – | 0.00 (0.00, Inf) | 0.999 |

| Luminal B | 3.30 (1.12–9.69) | 0.030 | 3.12 (1.03–9.47) | 0.045 |

| Luminal A (Reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Normal | 2.98 (0.35–25.57) | 0.320 | 3.75 (0.41–34.01) | 0.241 |

| High Clinical Risk (via Adjuvant! Online) | 1.23 (0.43–3.51) | 0.704 | ||

Abbreviations: LRR = locoregional recurrence, UVA = univariate analysis, MVA = multivariate analysis, HR = hazard ratio, AA = African American, IDC = invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC = invasive lobular carcinoma, pTNM = pathologic tumor-node-metastasis stage, XRT = external radiotherapy, PMRT = post-mastectomy radiation treatment, BCT = breast conserving treatment, LVSI = lymphovascular space invasion.

Statistically significant values are in bold

4. Discussion

In the literature, in comparison to younger patients, older patients with breast cancer have higher rates of the luminal molecular subtypes, which are associated with improved clinical outcomes [7,12,21]. Because of this, as well as their increased comorbidities, older patients with breast cancer are typically treated conservatively [14,22,23]. In contrast to their favorable prognostic features, prior studies have established that older patients with breast cancer have inferior rates of breast cancer specific mortality [9,12,24], even within hormone positive disease [10,11]. The present study found similar results, as patients 75 years or older had inferior OS (Table 3, Fig. 2A). However, the causes for these poor outcomes amongst older patients with breast cancer remain unclear.

We found that older patients had higher rates of the luminal B subtype (52.9% vs 34.4%). Prior studies have also found that a significant proportion of older patients with breast cancer harbor the luminal B subtype (17.5–37%) [9,21,25-27]. However, this was the first study to our knowledge to demonstrate that a majority of older patients harbor the this aggressive subtype. This difference in the proportion of the luminal B subtype within older patients can in part be explained by important dissimilarities in the inclusion criteria and molecular subtype methods of these studies. Two of the prior studies utilized an immunohistochemistry algorithm for molecular subtyping [9,26]. While de Kruijf et al. demonstrated that 37% of older patients harbor the luminal B subtype, they included patients with any ER and HER2 status, used a lower age cutoff (65 years), and utilized a different gene expression microarray platform (Illumina) from the present study (Affymetrix) [21]. Jenkins et al. found that 32% of women ≥70 years of age with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer harbored the luminal B subtype [27]. However, this large study included patients from multiple data sets with different gene expression platforms, including both Affymetrix and Agilent. While these important differences amongt the studies may not account for all of the discrepancy in the results, there is consensus that a significant percentage of older patients with breast cancer harbor the luminal B subtype.

We found that the luminal B subtype predicted for inferior outcomes, both amongst younger (5-year OS 96% v 87%, Fig. 2A; 5-year RFi 93% v 81%, Fig. 2B) and amongst older patients (5-year OS 78% v 64%, Fig. 2A; 5-year RFi 100% v 79%, Fig. 2B). Prior studies have also demonstrated that the luminal B subtype portends an inferior prognosis [9,25,26,28]. De Kruijf et al. demonstrated that molecular subtypes were significant prognostic factors in young patients with breast cancer (patients <65 years old), but not in older patients (patients ≥65 years old) [21]. However, Jenkins et al. found that molecular subtype was significantly associated with both RFS and disease-specific survival, even amongst patients ≥70 years old [27]. In a study of 1362 patients with breast cancer ≥65 years old, Engels et al. found that in comparison to the luminal A subtype, the luminal B subtype predicted for inferior survival (10-year survival 67% vs 88%) [25]. While not significant, there was a trend toward inferior relapse free period for the luminal B subtype (5-year recurrence 18% vs 11%).

In our study, several classic oncologic risk factors, including those within the Adjuvant! Online clinical risk algorithm, did not significantly predict for OS, RFi, or LRR in ER+/HER2− post-menopausal patients with invasive breast cancer. De Glas et found similar results, as Adjuvant! Online did not accurately predict overall survival or recurrence in patients ≥65 years old with early breast cancer [29]. Another study demonstrated that while classic oncologic prognostic factors such as molecular subtype, grade, and stage did account for a significant aspect of prognosis amongst younger patients with breast cancer, these factors did not explain the poor prognosis amongst patients ages 70–89 [9]. In fact, there was a significantly higher proportion of the luminal B subtype within grade 1–2 (49.2% vs 30.2%) and clinical “low risk” (50.0% vs 25%) disease in patients ≥75 years-old. (Table 2) Therefore, it appears that in the post-menopausal population, molecular subtyping confers significant prognostic utility in addition to standard clinical risk factors.

Older patients are more often treated conservatively, though multiple studies have demonstrated improved outcomes with more aggressive treatment [9,14,15,22,23]. The CALGB 9343 and PRIME II trials demonstrated that patients ≥70 years and ≥ 65 years, respectively, with low clinical risk breast cancer may be safely spared adjuvant radiotherapy, and there has been a recent decline in the use of adjuvant radiotherapy for older patients with early stage, ER+ breast cancer [23,30,31]. However, the prognosis for these patients is dependent upon adherence to hormone therapy for 5 years. Indeed, in our study, we found that older patients were less often prescribed hormone therapy (71% vs 89%, Table 1), and the receipt of hormone treatment is associated with superior OS (Table 3), RFi (Table 4), and LRR (Table 5). Recent literature has shown that even within those that begin hormone therapy, a significant proportion of patients are nonadherent [32,33]. This is especially problematic for luminal B patients, as Yu et al. demonstrated that patients with luminal B breast cancer have a significantly higher risk of distant recurrence when compared to the luminal A subtype [28]. Specifically, those patients with luminal B disease who do not complete postoperative hormone therapy are at the greatest risk for distant spread of disease within the first five years after surgery (approximately 33% with no endocrine therapy versus approximately 12% with endocrine therapy). This is of particular importance for older patients, as they are more likely to be nonadherent to adjuvant hormone therapy [33].

There are several important limitations of the present study, including its non-randomized and retrospective nature, limited follow up, and small sample size. Additionally, causes of death were unavailable in the present study, and therefore, overall survival was utilized as an endpoint. As the older subgroup is likely to have higher rates of comorbidities and death unrelated to breast cancer, breast cancer-specific survival would be a much more informative endpoint. Finally, genomic recurrence scores, such as Oncotype DX and MammaPrint, were not available for analysis.

Our results demonstrate that while older patients with breast cancer suffer inferior outcomes, standard clinical risk factors may not be reliable in patients ≥75 years. Because a signficiant number of older patients with breast cancer harbor aggressive molecular subtypes, genomic tests may improve prognostication and aid selection of appropriate candidates for treatment intensification.

Acknowledgements

Funding support from the Morton Plant Mease Foundation. Support for genomic data from Total Cancer Care research protocol and Merck & Co. This work has been supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, a NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30-CA076292).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Kamran A. Ahmed has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Genentech. Loretta Loftus reports that she owns stock in Johnson & Johnson, Elidilly, Amgen, Pfizer, and Gilead. She serves on the advisory board for Cardinal Health, AthenaX, Daichi, Castle, Biotheranostics, and Targeted Oncology, and on the development committee for Tyme inc.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68(1):7–30. 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 2004;291(22):2720–6. 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Talarico L, Chen G, Pazdur R. Enrollment of elderly patients in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 7-year experience by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(22):4626–31. 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sparano JA TAILORx: trial assigning individualized options for treatment (Rx). Clin Breast Cancer 2006;7(4):347–50. 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cardoso F, Van’t Veer L, Rutgers E, Loi S, Mook S, Piccart-Gebhart MJ. Clinical application of the 70-gene profile: the MINDACT trial. J Clin Oncol 2008;26(5):729–35. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van de Water W, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, et al. External validity of a trial comprised of elderly patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106(4):dju051. 10.1093/jnci/dju051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Diab SG, Elledge RM, Clark GM Tumor characteristics and clinical outcome of elderly women with breast cancer.J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(7):550–6. 10.1093/jnci/92.7.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status.J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106(5). 10.1093/jnci/dju055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Johansson ALV, Trewin CB, Hjerkind KV, Ellingjord-Dale M, Johannesen TB, Ursin G. Breast cancer-specific survival by clinical subtype after 7 years follow-up of young and elderly women in a nationwide cohort. Int J Cancer 2019;144(6):1251–61. 10.1002/ijc.31950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].van de Water W, Markopoulos C, van de Velde CJ, et al. Association between age at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality among postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. JAMA 2012;307(6):590–7. 10.1001/jama.2012.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu YR, Jiang YZ, Yu KD, Shao ZM. Different patterns in the prognostic value of age for breast cancer-specific mortality depending on hormone receptor status: a SEER population-based analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22(4):1102–10. 10.1245/s10434-014-4108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lodi M, Scheer L, Reix N, et al. Breast cancer in elderly women and altered clinico-pathological characteristics: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;166(3):657–68. 10.1007/s10549-017-4448-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Azim HA Jr, Nguyen B, Brohee S, Zoppoli G, Sotiriou C. Genomic aberrations in young and elderly breast cancer patients. BMC Med 2015;13:266. 10.1186/s12916-015-0504-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee CM, Zheng H, Tan VK, et al. Surgery for early breast cancer in the extremely elderly leads to improved outcomes - an Asian population study. Breast 2017;36:44–8. 10.1016/j.breast.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G, et al. Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women.J Clin Oncol 2003;21 (19):3580–7. 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Welsh EA, Eschrich SA, Berglund AE, Fenstermacher DA. Iterative rank-order normalization of gene expression microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14:153. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits ofhuman breast tumours. Nature 2000;406(6797):747–52. 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gendoo DM, Ratanasirigulchai N, Schroder MS, et al. Genefu: an R/Bioconductor package for computation of gene expression-based signatures in breast cancer. Bioinformatics 2016;32(7):1097–9. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(W1):W90–7. 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14:128. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].de Kruijf EM, Bastiaannet E, Ruberta F, et al. Comparison of frequencies and prognostic effect of molecular subtypes between young and elderly breast cancer patients. Mol Oncol 2014;8(5):1014–25. 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gal O, Ishai Y, Sulkes A, Shochat T, Yerushalmi R. Early breast cancer in the elderly: characteristics, therapy, and long-term outcome. Oncology 2018;94(1):31–8. 10.1159/000480087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rutter CE, Lester-Coll NH, Mancini BR, et al. The evolving role of adjuvant radiotherapy for elderly women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 2015;121(14):2331–40. 10.1002/cncr.29377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bergen ES, Tichy C, Berghoff AS, et al. Prognostic impact ofbreast cancer subtypes in elderly patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016;157(1):91–9. 10.1007/s10549-016-3787-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Engels CC, Kiderlen M, Bastiaannet E, et al. The clinical prognostic value of molecular intrinsic tumor subtypes in older breast cancer patients: a FOCUS study analysis. Mol Oncol 2016;10(4):594–600. 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Durbecq V, Ameye L, Veys I, et al. A significant proportion of elderly patients develop hormone-dependant “luminal-B” tumours associated with aggressive characteristics. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;67(1):80–92. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jenkins EO, Deal AM, Anders CK, et al. Age-specific changes in intrinsic breast cancer subtypes: a focus on older women. Oncologist 2014;19(10):1076–83. 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yu NY, Iftimi A, Yau C, et al. Assessment of long-term distant recurrence-free survival associated with Tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal patients with luminal a or luminal B breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2019. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].de Glas NA, van de Water W, Engelhardt EG, et al. Validity of adjuvant! Online program in older patients with breast cancer: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15(7):722–9. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(19):2382–7. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kunkler IH, Williams LJ, Jack WJ, Cameron DA, Dixon JM, investigators PI. Breast-conserving surgery with or without irradiation in women aged 65 years or older with early breast cancer (PRIME II): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16(3):266–73. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Broman K, Sun W, Zhou JM, Fridley B, Diaz R, Laronga C. Outcomes of selective whole breast irradiation following lumpectomy with intraoperative radiation therapy for hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Am J Surg 2019;218(4):749–54. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(27):4120–8. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]