Abstract

Modern morphological and structural studies are coming to a new level by incorporating the latest methods of three-dimensional electron microscopy (3D-EM). One of the key problems for the wide usage of these methods is posed by difficulties with sample preparation, since the methods work poorly with heterogeneous (consisting of tissues different in structure and in chemical composition) samples and require expensive equipment and usually much time. We have developed a simple protocol allows preparing heterogeneous biological samples suitable for 3D-EM in a laboratory that has a standard supply of equipment and reagents for electron microscopy. This protocol, combined with focused ion-beam scanning electron microscopy, makes it possible to study 3D ultrastructure of complex biological samples, e.g., whole insect heads, over their entire volume at the cellular and subcellular levels. The protocol provides new opportunities for many areas of study, including connectomics.

Subject terms: Imaging, 3-D reconstruction, Zoology, Entomology, Microscopy, Scanning electron microscopy, Transmission electron microscopy

Introduction

In recent years, methods for 3D study of the ultrastructural organization of organisms have been actively developed. Until recently, the only way to study spatial organization at the cellular and subcellular levels at a high definition was to examine series of ultrathin sections using a transmission electron microscope (TEM), now a number of new methods and devices have been developed1–3, such as the automated tape-collecting ultramicrotome (ATUM4), scanning electron microscope with integrated microtome (SBF-SEM5), focused ion-beam scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM6–8), gas cluster ion beam scanning electron microscope (GCIB-SEM9), and others. Modern 3D electron microscopes make it possible to quickly and efficiently obtain information on the structure of rather large samples at the subcellular level, which makes a considerable contribution to understanding the structure and ultrastructure of cells and tissues. For examining samples of insects and other organisms that have hard integuments, these methods can be insufficiently useful, since serial cutting of these samples is extremely difficult due to the chipping cuticle, which deforms the sections.

Classical methods for preparing samples for electron microscopy do not provide sufficient contrast of samples, because they were designed for using additional staining of sections10–12, which is impossible with many methods of 3D-EM. The widely used sample preparation methods for FIB-SEM and SBF-SEM work well only on pieces of homogeneous tissue13,14. Currently, protocols are being actively developed that will enable the study of large tissue samples15, such as whole fruit fly brains16–18, zebrafish brains19, or even mouse brains20,21 but these protocols cannot be used for the en block staining of whole insect head, since they do not provide uniform quality for a heterogeneous sample (consisting of dissimilar tissues dissimilar in structure and composition). The success of specimen fixation and contrasting is largely determined by the rate of penetration of the reagents into the sample11,22, which is considerably slowed down in heterogeneous samples with the presence of a poorly permeable integument or of tissues with a high lipid content. Such problems with sample preparation are noted for insects23,24 and other arthropods 25, other invertebrates25–28 and vertebrates29, as well as plants 30.

The goal of this study is to develop a protocol for the preparation of heterogeneous biological samples for 3D-EM. The 3D-EM methods in connectomics are most in demand; our attention was therefore focused on the brains of the sampled insects.

Results and discussion

In the search for the optimal protocol, we have tested all currently used protocols for preparing samples for 3D-EM, but all of them do not provide acceptable results for studying whole insect heads (Figs. 1, 2, S1, S2). We have also tested over 300 protocols combining various options for all stages of sample preparation (Table S1).

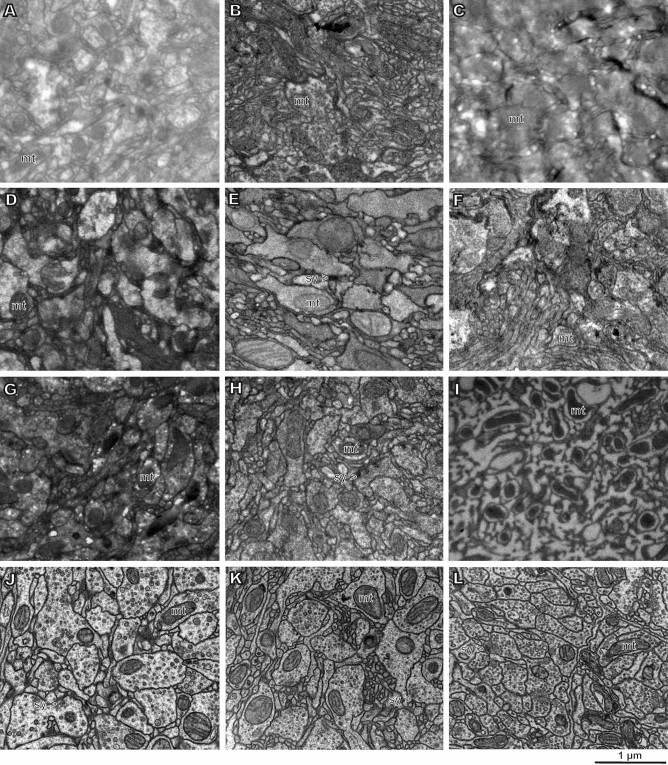

Figure 1.

Comparison of the results of various protocols for preparation of whole heads of parasitoid wasp Megaphragma amalphitanum (TEM, areas of neuropil from middle regions of the brain). (A) Classical fixation with GA and staining with OsO410; (B) OTO34; (C) GA + PFA, RO and TA13; (D) GA + PFA, OTO, UA, PbAsp14; (E) GA + PFA, ROTO, UA, PbAsp35; (F) GA, BROPA21; (G) GA + PFA, OsO4, FeCN, TCH, OsO4, UA, PbAsp 15; (H) GA + PFA, PLT16; (I) HPF and ASF16; (J) our protocol; (K) our protocol accelerated; (L) our protocol MW. mt, mitochondrion; sy, synapse.

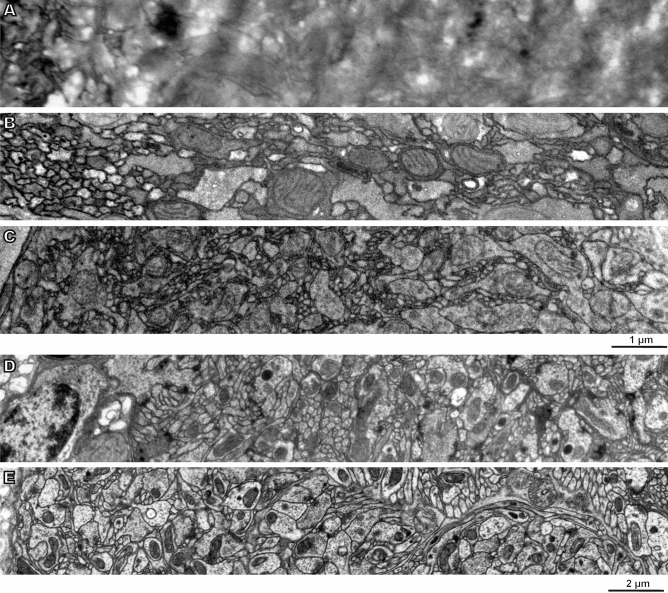

Figure 2.

Comparison of the homogeneity of contrasting for samples of the brain of the parasitoid wasp Megaphragma amalphitanum from peripheral regions (left) to central regions (right) in samples prepared according to different protocols (TEM). (A) RO and TA13; (B) ROTO, UA, PbAsp35; (C) Permanganate36; (D) PLT16; (E) our protocol.

As a result, we have developed a protocol based on simultaneous fixation with glutaraldehyde (GA) and osmium (OsO4)31, sequential osmification and treatment of samples with potassium ferrocyanide (FeCN)15, staining of samples with uranyl acetate (UA) with heating to 50 °C32, staining with lead aspartate (PbAsp)33. Other important components of our protocol include prolonged osmification, absence of moderators and of subsequent second osmification, prolonged washing between stages, and great duration of exposure during dehydration and embedding.

Fixation is one of the most critical stages in the preparation of heterogeneous samples; this problem is especially acute for samples of insects, since their cuticle is impermeable or weakly permeable to most of the fixatives used, and their fat bodies, rich in lipids, also cause difficulties. Standard fixation, GA or GA + formaldehyde (PFA), does not allow attaining sufficient fixation quality (Fig. 1A,C–H). The use of additional agents (picric acid, tannic acid, etc.) in combination with aldehyde fixation improves the quality of fixation, but increases the uneven penetration of fixatives and contrast agents or reduces the contrast between cell structures and cytoplasm. Primary fixation with an osmium solution does not allow obtaining preparations with well-preserved membranes (Fig. 1B), and samples fixed with reduced osmium solution (RO, mixture of OsO4 and FeCN) have a low contrast and are additionally spoiled by precipitation of metals. Permanganate fixation allows obtaining very contrasting images of membranes, but other components of cells are destroyed, and the fixation is uneven. High-pressure freezing with subsequent automatic freeze substitution (HPF + AFS) does not provide the needed quality and uniformity of fixation (Fig. 1I), apparently due to the fact that the cuticle can play the role of a thermal barrier. The best quality of the samples was obtained using simultaneous fixations with 1% GA + 1% OsO4 (Fig. 1J–L). For the other tested variants of fixation and subsequent stages, see Table S1.

The second critical stage is the staining of the samples. The standard single osmification is not enough to obtain the desired level of contrast (Fig. 1A). Staining with RO provides for good preservation of the ultrastructure and for high contrast, but it is accompanied by precipitation of metals in the tissues. Staining with permanganate allows obtaining very contrasting membranes, but the other components of the cells are completely destroyed, and the contrast is uneven throughout the depth of the sample (Fig. 2C). Multiple osmification (OTO34, ROTO35, ROTAO13, BROPA21, etc.) in combination with moderators [thiocarbohydrazide (TCH), tannic acid (TA), pyrogallol, etc.] makes it possible to obtain contrasting samples, but the contrast level is uneven throughout the depth of the sample (Fig. 2A,B) and precipitation takes place in tissues (Fig. 1C–G). Staining after progressive lowering of temperature (PLT)16 together with standard fixations does not provide for even fixation quality and contrast of the sample (Fig. 1H). Testing various staining methods has shown that the optimal method is multistep staining with sequential treatment of the samples with OsO4, FeCN, UA, PbAsp (Fig. 1J–L). Heating to 50 °C at the last two stages allows considerably increasing the contrast.

Comparison of different dehydration variants has shown that the optimal variant is to use the ethanol series (EtOH 30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, 100%) at 4 °C, followed by final dehydration in acetone (Ac) or propylene oxide (PO). Dehydration only in Ac or PO leads to the deformation of tissues. Due to the presence of the cuticle, sufficiently long exposure durations are required at all stages of dehydration (at least 30–60 min at each stage).

A comparison of the results of scanning samples concluded in Epon, Durcupan, Araldite, Spurr, Hard-Plus resin. We have shown that the most contrasting and detailed picture is obtained using Epon 812. On the other hand, Durcupan and Hard-Plus resin give most moderate of artifacts when examining the samples using FIB-SEM, which makes it possible to scan larger samples.

Samples prepared according to our protocol combine a high degree of preservation of the anatomy and ultrastructure with a contrast sufficient for studying the samples using FIB-SEM, SBF-SEM, and TEM without staining the sections (Figs. 1J, 2E, 3). The variants of the protocol at different stages of optimizing it have already been used to study the ultrastructure of the eyes of featherwing beetles (Coleoptera: Ptiliidae)24, the connectome of the optic lobes of Megaphragma wasps (Chua et al., in prep.), and the ultrastructure of the sensory organs of Megaphragma wasps (Diakova et al., in prep; Makarova et al., in prep.).

Figure 3.

Half of one cross section of the complete 3D-EM (FIB-SEM) series of the whole head of parasitoid wasp Megaphragma amalphitanum (A) and close-up of its fragments (B–F). (B) neuropil of a peripheral region of the brain; (C) neuropil of the central region of the brain; (D) central area of compound eye; (E) muscle; (F) fat body. Li, lipid inclusion; mf, muscular fiber; mt, mitochondrion; nu, nucleus; pg, pigment granule; rd, rhabdom; sy, synapse. Sample prepared according to our protocol. For sections of the same stack in other planes, see Figs S1, S2.

Many modern methods of sample preparation require complex and expensive equipment (High-pressure freezer, Microwave processor, Automatic freeze substitution system). The protocol we have developed does not require anything but standard equipment available in most laboratories working with EM (Supplement).

If necessary, this time can be reduced to 3 days by replacing most stages at 4 °C with shorter ones at room temperature (RT) and polymerization of the embedding medium at a higher temperature (Fig. 1K). But an increase in temperature leads to tissue shrinks, which in combination with the strong cuticle of the head can result in the rupture of tissues attached to it. Another option to reduce sample preparation time is to use microwave radiation to accelerate the processes (Fig. 1L), but in this case the level and evenness of contrast are not always good. For different samples, depending on their sizes and permeability, it may be necessary to optimize our protocol, mainly by changing the selection of the optimal concentration of fixatives and fixation duration at stages I, III, and V of sample preparation, and by the selection of the optimal molarity of the buffer used. For small and/or highly permeable samples, the concentration of the fixatives at stages I and V and the duration of stages I, III and V can be halved, as well as the duration of washing the samples after these stages and the duration of dehydration. For large and/or poorly permeable samples, it is possible to increase the fixation time at stage I to 85 min and at stage II by a factor of 2–3. Recently proposed modifications of PLT18 could possibly allow to complement our protocol and further improve the contrast of the samples.

The choice of the microscope is also instrumental for successfully solving the problems of 3D-EM. Working with SBF-SEM has its advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include the high speed of this work and the opportunity to obtain images of large samples (their size limited by the size of the diamond knife and the required Z step). But the disadvantages make this method useless for many objectives. The main disadvantage is the fact that obtaining thin sections from samples that include the cuticle or other hard components often leads to chipping of the cuticle and to deformation of the block surface, which distorts the resulting image. But for soft tissues SBF-SEM makes it possible to obtain high-quality images of samples prepared according to our protocol (Fig. S3). Using FIB-SEM solves problems that arise when working with SBF-SEM, but ion etching also has some limitations, mainly those concerning the etching depth, which is limited by the ability to focus the ion beam. Different kinds of ion scanning microscopes can produce data of different quality. A modified FIB-SEM used in the laboratory of Harald Hess (Janelia)7,8, in which the ion column and electron column are oriented at 90 degrees to each other and several multilevel control systems for the main components of the system are introduced. This microscope allows obtaining high-resolution (4 × 4 × 4 nm along X × Y × Z) and high-contrast images for samples of large volumes (the system is able to work stably without stopping for several months and makes it possible to study samples up to 100 µm thick)7,8. FIB-SEM settings require rather many preliminary experiments for each sample type, since the choice of the ion beam current, electron gun voltage, scanning frequency, and many other parameters depend on the type of the sample, its size, the staining variant, and the embedding medium.

Conclusions

As a result of testing the principal protocols used to prepare samples for electron microscopy and different variants of combinations of all their stages, we have developed a simple protocol for sample preparation of heterogeneous biological samples for 3D-EM. This protocol can be useful for studying the ultrastructure of various organisms using FIB-SEM and SBF-SEM and for facilitating work with TEM, since it does not require staining of sections. The protocol has been successfully tested on various insects; it allows making preparations of whole heads or even whole bodies, giving new opportunities for large-scale studies of the ultrastructure of organisms at the cellular and subcellular levels. It is especially useful for connectomics, helping to study not only the brain at the cellular level but also the ultrastructure of receptors and their projections into the brain and the effector pathways that exit the brain. All this together suggests that the protocol will be in demand for solving various problems by researchers working in a broad range of areas.

Materials and methods

Studied species

The main model used in this study is the parasitoid wasp Megaphragma amalphitanum Viggiani, 1997 reared in the laboratory from eggs of Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Bouché, 1833). The principal variants of sample preparation were tested also on featherwing beetles Nephanes titan (Newman, 1834) collected at the Zvenigorod Biological Station, Lomonosov Moscow State University, and on the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster Meigen, 1830 from a culture maintained at the Department of Genetics, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Protocol

All our experiments were performed on whole heads, which were separated from the body in a fixative on glass slides with cavities and immediately transferred into fresh fixative. Fixation, staining, dehydration, and infiltration were performed in plastic tubes; the volume of all liquids was at least 1000 times as great as that of the sample; the process solutions were changed automatically or with a disposable dropper without transferring the sample from one tube to another. For the chemicals, supplies, and equipment, see Supplement.

-

I.

Immediately after dissection in fixative 1, the samples were transferred to fresh fixative 1 and kept for 45 min at 4 °C (Toxic). Fixative 1, 1% glutaraldehyde (GA) and 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2 (CB). (Critical: prepare the fixative immediately prior to fixation, monitoring the temperature at all stages of fixation; if the samples are poorly wettable and adhere to the surface film of the liquid, it is necessary to make them sink and make sure that they do not float at this stage or at any of the subsequent stages)

-

II.

Washing samples in 0.1 M CB, two changes with a total duration of 20 min at 4 °C (Toxic)

-

III.

Fixation with fixative 2 (2% GA in 0.1 M CB) for 2 h at 4 °C (Toxic)

-

IV.

Washing the samples in 0.1 M CB, four changes with a total duration of 2.5 h at 4 °C (Toxic)

-

V.

Postfixation and staining with a buffer solution of osmium tetroxide (2% OsO4 in 0.1 M CB) for 12 to 20 h at 4 °C (Toxic)

-

VI.

Treatment with buffer solution with potassium ferrocyanide (1% FeCN in 0.1 M CB) for 2 h at 4 °C (Toxic)

-

VII.

Washing the samples with double distilled water (ddH2O), four changes with a total duration of 2.5 h at 4 °C

-

VIII.

Staining with an aqueous solution of uranyl acetate (UA) with heating to 60 °C (1% UA in ddH2O for 8–12 h at 4 °C, then in the same solution for 2 h at 50 °C in a constant temperature oven). (Critical: use only fresh ddH2O) (Toxic)

-

IX.

Washing the samples with ddH2O, four changes with a total duration of 2 h at RT

-

X.

Staining with lead aspartate according to Walton (PbAsp, 0.66% lead nitrate in 0.03 M aspartic acid, pH adjusted to 5.5 with 1 M KOH) for 2 h at 50 °C (Toxic)

-

XI.

Washing the samples with ddH2O, four changes with a total duration of 2.5 h at RT

-

XII.

Dehydration in ethanol of increasing concentrations (EtOH) and acetone (Ac)

-

1.

EtOH 30% for 30 min at 4 °C

-

2.

EtOH 50% for 30 min at 4 °C

-

3.

EtOH 70% for 60 min at 4 °C

-

4.

EtOH 95% for 60 min at 4 °C

-

5.

EtOH 100% for min at 4 °C. (Critical: dry EtOH)

-

6.

EtOH 100% for 30 min at RT. (Critical: dry EtOH)

-

7.

EtOH 100% + Ac for 30 min at RT. (Critical: dry EtOH and Ac)

-

8.

Ac for 30 min at RT. (Critical: dry Ac)

-

9.

Ac for 30 min at RT. (Critical: dry Ac)

-

XIII.

Placing in embedding medium (Epon 812)

-

1.

Mixture of Epon and acetone (1: 2) for 2 h at RT in rotator at 1 rpm. (Critical: dry Ac) (Toxic)

-

2.

Mixture of Epon and acetone (1: 1) for 24 h at RT in rotator at 1 rpm. (Critical: dry Ac) (Toxic)

-

3.

Epon for 2 h at RT in rotator at 1 rpm (Toxic)

-

4.

Epon for 5 h at RT in rotator at 1 rpm (Toxic)

-

XIV.

Polymerization of Epon for 48 h at 60 °C in silicon embedding molds. (Toxic)

Protocol variants

Accelerated sample preparation. Sequence and the contents of the operations are the same as in the original protocol, but stages II–VII at RT, stage XIV at 95 °C, duration of stages III, IV, VI, VII 1 h, duration of stage V 4 h, and duration of stage XIV 2 h.

Using a microwave processor. The sequence and contents of the operations is the same as in the original protocol, but stages I–VII in a microwave processor in an ice bath at a power of 200 W according to the following On (Off) scheme for microwaves:

I—0.5 (0.5) 0.5 (0.5) 0.5 (1) 0.5 (1) 0.5 (10) 1 (10) 1 (10)

II—0.5 (5)

III—0.5 (0.5) 0.5 (0.5) 1 (1) 1 (20) 1 (30)

IV—0 0.5 (5), change of 0.1 M CB, 1 (30), change of 0.1 M CB, 1 (30)

V—0.5 (1) 0.5 (1) 0.5 (1) 1 (20) 1 (30)

VI—0.5 (1) 0.5 (1) 0.5 (1) 1 (10) 1 (20)

VII—0.5 (5), change of ddH20, 1 (30), change of ddH20, 1 (30)

XIV—2 h at 95 °C in microwave processor or constant temperature oven.

Microscopy

Assessment of the preservation of the general anatomy was performed using a series of histological sections made using a Leica RM 2255 microtome and studied under an Olympus BX43 microscope. Initial assessment of the quality of the ultrastructure of transmission electron microscope samples (Jeol JEM-1011 and JEM-1400, Lomonosov Moscow State University) was performed on sections of 40–50 nm made using a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome; these samples at the early stages of the choice of fixatives were standard stained with lead citrate and UA and at subsequent stages, including en block staining, were studied without additional staining of sections. Quality samples were then tested at FIB-SEM (FEI Quanta FEG, Moscow State University, or FEI Helios, Kurchatov Institute), and the best samples were sent to the Janelia Research Campus (United States) for scanning on a modified FIB-SEM (Zeiss Merlin + Capella) or to the FEI Research Center (United States) for scanning on a SBF-SEM (FEI Teneo). Before scanning, sample quality was evaluated using an X-ray micro-CT (Xradia Versa 3D XRM-510). The large-scale imaging of the Megaphragma was done with a Zeiss Merlin scanning electron microscope that has a Zeiss Capella focused ion beam column mounted on at 90 degrees and controlled by custom software7,8. To image an entire head we used 2 MHz pixel rates with a 2nA primary electron beam with final voxels that were sampling at 8 × 8 nm in x and y and milled with effective 8 nm increments. To image such large volumes, (> 100 micron size) required continuous stable image acquisition for about a month.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dmitri 'Mitya' Chklovskii (Flatiron Institute), one of the initiators of this study, for his help and useful discussions. We are also grateful to the staff of the Electron Microscopy Laboratory, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, without whose help this study could never be completed, to members of the Research Resource Center for Molecular and Cell Technologies, St. Petersburg State University, and Laboratory of Electron Microscopy, National Research Center “Kurchatov Institute.” We thank Vladimir V. Yushin (National Scientific Center of Marine Biology, FEB RAS) for his helpful discussions of the difficulties of preparing samples of different animal groups. This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (No. 17-04-00669, 20-04-00642).

Author contributions

A.A.P. designed the study; A.A.P. and A.A.M. prepared and tested the samples; S.P., C.S.X. and H.H. scanned the samples using FIB-SEM; A.A.P. wrote and edited the manuscript; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-83936-0.

References

- 1.Briggman KL, Bock DD. Volume electron microscopy for neuronal circuit reconstruction. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2012;22:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peddie CJ, Collinson LM. Exploring the third dimension: volume electron microscopy comes of age. Micron. 2014;61:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kremer A, et al. Developing 3D SEM in a broad biological context. J. Microsc. 2015;259:80–96. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayworth KJ, et al. Imaging ATUM ultrathin section libraries with WaferMapper: A multi-scale approach to EM reconstruction of neural circuits. Front. Neural Circuits. 2014;8:68. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denk W, Horstmann H. Serial block-face scanning electron microscopy to reconstruct three-dimensional tissue nanostructure. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knott G, Marchman H, Wall D, Lich B. Serial section scanning electron microscopy of adult brain tissue using focused ion beam milling. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2959–2964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu CS, et al. Enhanced FIB-SEM systems for large-volume 3D imaging. Elife. 2017;6:e25916. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu, C. S., Pang, S., Hayworth, K. J. & Hess, H. F. Enabling FIB-SEM systems for large volume connectomics and cell biology. bioRxiv, 852863 (2019).

- 9.Hayworth KJ, et al. Gas cluster ion beam SEM for imaging of large tissue samples with 10 nm isotropic resolution. Nat. Methods. 2020;17:68–71. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0641-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayat MA. Principles and Techniques of Electron Microscopy: Biological Applications. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayat MA. Fixation for Electron Microscopy. Cambridge: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maunsbach AB, Afzelius BA. Biomedical Electron Microscopy. Cambridge: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushby AJ, et al. Imaging three-dimensional tissue architectures by focused ion beam scanning electron microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tapia JC, et al. High-contrast en bloc staining of neuronal tissue for field emission scanning electron microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:193–206. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hua Y, Laserstein P, Helmstaedter M. Large-volume en-bloc staining for electron microscopy-based connectomics. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7923. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayworth KJ, et al. Ultrastructurally smooth thick partitioning and volume stitching for large-scale connectomics. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:319–322. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng, Z. et al. A complete electron microscopy volume of the brain of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Cell174, 730–743 e722 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lu, Z. et al. En bloc preparation of Drosophila brains enables high-throughput FIB-SEM connectomics. bioRxiv, 855130 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Genoud C, Titze B, Graff-Meyer A, Friedrich RW. Fast homogeneous en bloc staining of large tissue samples for volume electron microscopy. Front. Neuroanat. 2018;12:76. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikula S, Binding J, Denk W. Staining and embedding the whole mouse brain for electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1198–1201. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikula S, Denk W. High-resolution whole-brain staining for electron microscopic circuit reconstruction. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozzola J, Russell L. Electron Microscopy: Principles and Techniques for Biologists. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonald KL, Sharp DJ, Rickoll W. Preparation of Drosophila specimens for examination by transmission electron microscopy. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2012;2012:1044–1048. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top068452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makarova AA, Meyer-Rochow VB, Polilov AA. Morphology and scaling of compound eyes in the smallest beetles (Coleoptera: Ptiliidae) Arthropod. Struct. Dev. 2019;48:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.asd.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zooplankton fixation and preservation. (The Unesco Press, Paris, 1976).

- 26.Jones JT, Gwynn IA. A method for rapid fixation and dehydration of nematode tissue for transmission electron microscopy. J. Microsc. 1991;164:43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1991.tb03190.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lak B, et al. High-pressure freezing and freeze-substitution fixation reveal the ultrastructure of immature and mature spermatozoa of the plant-parasitic nematode Trichodorus similis (Nematoda; Triplonchida; Trichodoridae) Micron. 2015;77:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claeys M, et al. Self-pressurised rapid freezing, a time-efficient and affordable cryo-fixation method for ultrastructural observations on unhatched cyst nematodes. Nematology. 2019;22:103–110. doi: 10.1163/15685411-00003287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalt MR, Tandler B. A study of fixation of early amphibian embryos for electron microscopy. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1971;36:633–645. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5320(71)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson SM, Bacic A. Preparation of plant cells for transmission electron microscopy to optimize immunogold labeling of carbohydrate and protein epitopes. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:1716–1727. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall, D. H., Hartwieg, E. & Nguyen, K. C. Q. in Methods Cell Biol. Vol. Volume 107 (eds H. Rothman Joel & Singson Andrew) 93–149 (Academic Press, London, 2012).

- 32.Locke M, Krishnan N, McMahon JT. A routine method for obtaining high contrast without staining sections. J. Cell Biol. 1971;50:540–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.2.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walton J. Lead aspartate, an en bloc contrast stain particularly useful for ultrastructural enzymology. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1979;27:1337–1342. doi: 10.1177/27.10.512319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seligman AM, Wasserkrug HL, Hanker JS. A new staining method (OTO) for enhancing contrast of lipid-containing membranes and droplets in osmium tetroxide-fixed tissue with osmiophilic thiocarbohydrazide (TCH) J. Cell Biol. 1966;30:424–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holcomb PS, et al. Synaptic inputs compete during rapid formation of the calyx of Held: a new model system for neural development. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:12954–12969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1087-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luft JH. Permanganate; a new fixative for electron microscopy. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1956;2:799–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.2.6.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.