Abstract

The full length Andrographis paniculate 4-hydroxy 3-methyl 2-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase (ApHDR) gene of MEP pathway was isolated for the first time. The ApHDR ORF with 1404 bp flanked by 100 bp 5′UTR and 235 bp 3′UTR encoding 467 amino acids (NCBI accession number: MK503970) and cloned in pET 102, transformed and expressed in E. coli BL21. The ApHDR protein physico-chemical properties, secondary and tertiary structure were analyzed. The Ramachandran plot showed 93.8% amino acids in the allowed regions, suggesting high reliability. The cluster of 16 ligands for binding site in ApHDR involved six amino acid residues having 5–8 ligands. The Fe-S cluster binding site was formed with three conserved residues of cysteine at positions C123, C214, C251 of ApHDR. The substrate HMBPP and inhibitors clomazone, paraquat, benzyl viologen’s interactions with ApHDR were also assessed using docking. The affinity of Fe-S cluster binding to the cleft was found similar to HMBPP. The HPLC analysis of different type of tissue (plant parts) revealed highest andrographolide content in young leaves followed by mature leaves, stems and roots. The differential expression profile of ApHDR suggested a significant variation in the expression pattern among different tissues such as mature leaves, young leaves, stem and roots. A 16-fold higher expression of ApHDR was observed in the mature leaves of A. paniculata as compared to roots. The young leaves and stem showed 5.5 fold and fourfold higher expression than roots of A. paniculata. Our result generated new genomic information on ApHDR which may open up prospects of manipulation for enhanced diterpene lactone andrographolide production in A. paniculata.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-021-00952-0.

Keywords: Andrographis paniculata, HDR, Gene isolation, Andrographolide, qRT-PCR, Tissue specific gene expression

Introduction

Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees belongs to family Acanthaceae, commonly known as ‘King of bitters’ (Sajeeb et al. 2015). It is widely distributed in India, China and South East Asian countries (Neeraja et al. 2015). This plant has shown curative effects against various diseases mainly cancer (Kandanur et al. 2019; Rajaratinam and Nafi 2019). A. paniculata contains about 50 diterpene lactones, 30 flavonoids, 8 quinic acid derivatives, and 4 xanthones. The terpenoids are considered to be the primary specialized metabolites in this plant which play vital role in metabolism (Subramanian et al. 2012). In nature about 100,000 terpenoids were identified out of which about 12,000 belong to diterpenoid group alone. Different derivatives of the principle bioactive compound andrographolide i.e., neoandrographolide and dihydro- andrographolide has also shown immense therapeutic applications. Derivatives of andrographolide such as 3, 19-diacetyl-12-phenylthio-14-deoxy-andrographolide, has also shown prominent medicinal values as anti-HIV (Uttekar et al. 2012). Recently, green synthesis of nanoparticles using A. paniculata leaf extract has shown anti-bacterial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (Muthulakshmi et al. 2020). In a recent report, andrographolide nanocrystals has demonstrated hepatoprotective activity to drug induced liver injury (Basu et al. 2020) and anti-venom (Ghosh et al. 2020).

The two pathways namely cytosolic MVA and plastidial, methyl erythritol diphosphate pathway (MEP) are involved in biosynthesis of isopentyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) (Lange et al. 2000; Rodríguez-Concepción and Boronat 2002). The IPP and DMAPP subsequently lead to the production of diterpenes (Fig. 1). Both the MVA and MEP pathways are involved in the synthesis of precursors (IPP and DMAPP) and there exists the cross talk between cytoplasm and plastids (Srivastava and Akhila 2010). The MEP pathway is a seven step multi-enzyme pathway wherein the ultimate step is catalyzed by the enzyme 4-hydroxy 3-methyl 2-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase (HDR) (Xue et al. 2019). The HDR is also known as LytB or IspH and has been proved as key regulatory enzyme which converts HMBDB into IPP and DMAPP (Altincicek et al. 2002; Banerjee and Sharkey 2014). The HDR gene regulation has proved that the over expression is correlated with the biosynthesis of isoprenoids in plants. The up-regulation enhanced carotenoid production and controlled isoprenoid biosynthesis (Botella‐Pavía et al. 2004). The loss of function HDR gene led to albino phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana and also involved in rescuing E.coli HDR mutant strain (Guevara-García et al. 2005).

Fig. 1.

MEP (2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate) pathway for diterpenoid biosynthesis in plants. G3P-Glyseraldehyde 3-phosphate, DXP- 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, MEP- 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate, CDP-ME- 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methylerythritol, CDP-MEP- 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2-phosphate, ME-cPP- 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate, HMBPP- (E)-4-Hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate, IPP- Isopentenyl pyrophosphate, DMAPP- Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, GPP- geranyl pyrophosphate, GGPP- geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. DXS- DXP synthase, DXR- DXP reductoisomerase, CMS- CDP-ME synthase, CMK- CDP-ME kinase, MDS- MCSME-cPP synthase, HDS- HMBPP synthase, HDR- HMBPP reductase, GGDS- GGPP synthase. Source (Lange 2000)

In most recent reports, the gene isolation and characterization was carried out in various plants such as Gossypium arboretum (Mushtaq et al. 2020), Rosa hybrida (Khan et al. 2020) and Arabidopsis thaliana (Ziyuan et al. 2020). Our laboratory has a comprehensive research programme on molecular interventions in A. paniculata (Bindu et al. 2020; Srinath et al. 2020, 2021). Keeping in view the importance of HDR, a key regulatory enzyme, attempts has been made to isolate and clone the full length cDNA of ApHDR and its expression in E. coli. The differential gene expression studies were also carried out using various tissues of A. paniculata. We have also analyzed the putative protein using various bioinformatics approaches. As the bioactive molecule andrographolide has proved to be of immense medicinal importance, the molecular docking of the regulatory enzyme involved in its biosynthesis may give new insights into drug targets (Ershov 2007). The active structure of IspH which has shown its substrate reduction mechanism was studied in E.coli (Gräwert 2009). The structural and functional aspect of ApHDR by in silico characterization and docking studies and the differential gene expression studies will have significance for understanding of diterpene lactone biogenesis in A. paniculata.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Andrographis paniculata seeds were collected from Regional Research Centre of CSIR-CIMAP, Lucknow i.e. Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (CIMAP), Hyderabad, India and originated from the CSIR-CIMAP National Gene Bank Lucknow, India (Srinath et al. 2020, 2021). A. paniculata seeds were sown and plants were grown in net house of Centre for Plant Molecular Biology (CPMB), Osmania University, Hyderabad, India. The plants were watered twice a day and Hoagland solution (Hoagland and Arnon 1938) was given at regular intervals. The surface sterilized A. paniculata seeds were inoculated onto hormone free MS (Murashige and Skoog 1962) referred to as MSO medium and allowed to germinate at culture room conditions in dark at 25 ± 2 °C.

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

The healthy leaves (600 mg) from two week old in vitro grown A. paniculata seedlings were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and ground to fine powder. Total RNA was isolated using RNAiso Plus solution (DSS Takara Bio India Pvt. Ltd. India). The purity of RNA was checked on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantity was estimated using spectrophotometer (Eppendorf BioSpectrometer, Eppendorf AG 22,331, Hamburg, Germany). The first strand cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (DSS Takara Bio India Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India) following manufacturer’s instructions. The cycle conditions were 42 °C for 40 min and 95 °C for 3 min for cDNA synthesis and was utilized for PCR amplification.

PCR amplification and generation of ApHDR partial sequence

The degenerative primers were designed using conserved regions of HDR cDNA sequences from different plants, referring data in NCBI for the isolation of partial ApHDR fragments. Multiple sequence alignment was carried out using CLUSTALW and the conserved regions were identified for designing of the primers. The primers were analyzed using Oligoanalyser tool (https://eu.idtdna.com/calc/analyzer/) and are listed in Table 1. Gradient PCR was employed and the PCR conditions included 94 °C for 2 min, 94 °C for 1 min, 50–55 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1.30 min for 30 cycles, 72 °C for 5 min for final extension and 4 °C of holding temperature. The amplified PCR fragments were run on 1% (w/v) agarose gel, eluted with NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up column for gel extraction kit (DSS TAKARA Bio Inc. New Delhi, India) and given for sequencing. The partial sequence obtained after sequencing was submitted to NCBI.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study for ApHDR gene cloning in A. paniculata

| Primers used | Primer name | Primer sequence 5′-3′ direction |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerative primers | FP1a | GAGCATGGCDRTYBCBCTBCARTT |

| FP2 | GYRMDAAYTAYAAYMGKARRGG | |

| FP3 | GGMTNACNAAYGARRTBATYCRYAAYCC | |

| RP1b | TYTCYTGHAGRTGHGAWRTTRCTYG | |

| RP2 | CYKTCTCMACMARYTCRCC | |

| RP3 | GGDGTNGABGCRCCRGAWGTNACNCC | |

| 5′ RACE | 5′GSPc | GATTACGCCAAGCTTAACCGCAAGGGGTTTGGGCA |

| 3′ RACE | 3′GSP | GATTACGCCAAGCTTGCCATCGAGCGCACCACCCA |

| Full length gene cloning | FP FHDR | CACCATGGTGGTTTCACTGCAATACTG |

| RP FHDR | CGCCAACTGCAATGCCTCCTC |

aForward primers; bReverse primers; cGene specific primers

Isolation of full length ApHDR using 5′ and 3′ random amplification of c-DNA ends (RACE) PCR

The partial sequences were aligned and used for designing of gene specific primers 3′GSP (3′RACE) and 5′GSP (5′RACE) according to manufacturer’s instructions where a 15 bp homologous sequence was added to the 5′ end of both the primers (Table 1). The total RNA isolated from seedlings was used for synthesis of RACE–Ready first-strand cDNA using cDNASMARTer® RACE 5′/3′ kit (DSS Takara Bio India Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India). The RACE reaction mixture included, 15.5 µl PCR grade H2O, 25 µl 2xSeq amplification buffer, 1 µl Seq-amplification DNA polymerase, 2.5 µl 5′ or 3′ cDNA, 1 µl 10xUPM (Universal primer mix), 0.5 µl 5′ and 3′ GSPs. The PCR was carried out at 94 °C for 2 min for initial denaturation, 94 °C for 30 s, 70 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 3 min, (30 cycles) and 72 °C for 5 min for final extension and 4 °C holding temperature. RACE fragments were determined using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis which was subsequently eluted and given for sequencing. Both the 5′ and 3′ RACE amplified products were cloned into PUC-19 based vector, using In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech: DSS Takara Bio India Pvt. Ltd. New Delhi, India). Subsequently, ligated fragments were transformed into E. coli stellar competent cells as per the given protocol. The screening was done using appropriate antibiotic i.e., ampicillin 100 µg/ml in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium.

Cloning and expression of full length ApHDR gene in E.coli cells

The full length cDNA of ApHDR (1404 bp) was amplified using specific primers (Table 1). The PCR conditions were employed as follows: 94°C- 2 min, 94°C-1 min, 53°C-1 min, 72°C- 1.30 min for 30 cycles, 72°C-5 min. The amplified product of full length ApHDR cDNA was sub-cloned into pET TOPO expression vector (Champion pET 102 Directional TOPO Expression kit, Thermo Fischer Scientifics India Pvt. Ltd.), which was transformed into One Shot TOP10 chemically made competent E.coli cells as per the instructions. The resulting recombinant plasmid containing pET TOPO expression construct having ApHDR insert was then transformed into E.coli one shot BL 21Star (DE3) strain. The transformed recombinant cells were screened on LB medium containing appropriate antibiotic (Ampicillin 50 µg/ml) and 1% (w/v) glucose.

Induction of ApHDR recombinant protein in E. coli BL 21 strain

The over expression of recombinant ApHDR protein was observed and recorded on SDS-PAGE from induced and un-induced cultures. ApHDR recombinant protein induction was carried out using overnight liquid cultures of transformed BL21 initiated in liquid LB medium at 28 °C and 200 rpm. After attaining the desired OD at 600 nm, the culture was inoculated again into freshly prepared LB medium having IPTG at a final concentration of 1 mM as induced and without IPTG as control un-induced cultures. The cell density in the medium of control and induced samples was obtained at every 0, 1, 3, 6 and 24 h. The control and induced cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 1 min at 4°C and the pellets were kept at − 20 °C.

The frozen samples were prepared for SDS-PAGE analysis. The different cell pellet samples were thawed and suspended in 1XSDS-PAGE sample buffer and were kept in a boiling water bath for 5 min. All the samples were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE (Hoefer, Inc., CA, USA). The overnight staining was done using Coomassie brilliant blue followed by de-staining with solution containing 5% v/v CH3OH, 7% v/v CH3COOH, 88% v/v distilled H2O. Gel was washed with distilled water and observed under florescent light (Genaxy Scientific Pvt Ltd. New Delhi, India).

In silico bioinformatics analysis of ApHDR protein

ApHDR physico chemical properties, secondary structures, subcellular localization signals, transmembrane regions and three dimensional structure of ApHDR putative protein were predicted and analyzed (Table 2). The homologous nucleotide sequence search was carried out by NCBI Nucleotide Blast https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi. Conserved domain search was carried out using NCBI Conserved Domain Database search (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2017). The MSA of ApHDR and other plant proteins was carried out by CLUSTALW. The ligand binding site was predicted using 3DLigandSite-Ligand binding prediction server http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~3dligandsite/ (Wass et al. 2010).

Table 2.

List of Bioinformatic tools used in the present study

| Type of analysis | Online Tool | Website |

|---|---|---|

| ProtParam tool | Physico chemical properties | https://web.expasy.org/protparam/ |

| Predict protein | Composition of amino aicds | https://www.predictprotein.org/home |

| CFSSP prediction server | Composition of amino aicds | https://www.biogem.org/tool/chou-fasman/ |

| SOPMA | Secondary structure prediction | https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html |

| Three dimensional structure Phyre2 | http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index | |

| Three dimensional structure Swiss Model | http://swissmodel.expasy.org/ | |

| BaCelLo server | Localization ofdeducedproteins | http://gpcr2.biocomp.unibo.it/bacello/pred.htm |

| iPSORT software | Subcellular localization | http://ipsort.hgc.jp/ |

| cTP analysis | Choroplast transit peptide | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/ |

| Target P – 2.0 | Presence of N-terminal sequences | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/ |

| TMHMM server 2.0 | Trans-membraneregion | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/ |

| Conserved domain search | NCBI CDD search | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi |

| Multiple sequence alignment | Clustal Omega | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/ |

| Ligand binding site | 3D Ligand Site- Ligand binding prediction server | http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~3dligandsite/ |

| Structural validation by Ramachandran plot analysis | RAMPAGE | http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.php |

The phylogenetic tree of HDR proteins was constructed with neighbor joining (NJ) method using MEGA 7.0 software (Kumar et al. 2016). Three dimensional structural analysis was carried out using online server SWISS MODEL (Waterhouse et al. 2018) and Phyre2 servers (Kelley et al.2015).The models generated by Phyre2 and Swiss Models were structurally validated using Ramachandran plot analysis by RAMPAGE http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.php (Lovell et al. 2002).The quality check of this model was carried out using Phyre2 investigator server for Ramachandran plot, alignment confidence, ProQ2 quality assessment of the protein model. More than one tool was used for three dimensional structural analyses for the accuracy.

Molecular docking studies of ApHDR

The Molecular docking programme Molgro Virtual Docker (MVD, 2010.4.0.0) was used as the platform for molecular docking. The optimized structures of Fe-S cluster, and HMBPP (substrates), Clomazone, Paraquat and Benzyl viologen (inhibitors) were docked into the substrate binding site of ApHDR protein. The energy minimization and (Table 3) hydrogen bonds were optimized after the docking. The binding affinity and interactions of inhibitor with protein was analyzed on the basis of the internal electrostatic, internal hydrogen bond interactions and sp2-sp2 torsions.

Table 3.

Primers used for qRT-PCR analysis of ApHDR in A. paniculata

| Primers used | Primer name | Primer sequence 5′-3′ direction | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR analysis | ApHDRFPa | CGAACGGGCTGTTCAGATTG | 20 |

| ApHDRRPb | CATTTCGTCCACAGCAGCTC | 20 | |

| ApActinFPa | AAGAACTATGAGCTGCCCGA | 20 | |

| ApActinRPb | TCTCCTTGCTCATCCTGTCC | 20 |

a Forward primer, bReverse primer

HPLC analysis of andrographolide content and differential ApHDR gene expression in different plant parts

The resultant extracts of mature leaves, young leaves, stem and roots of healthy A. paniculata plants were filtered. About 500 µl of filtrate solution was taken and transferred into HPLC vials for analysis. The samples were prepared and analyzed for andrographolide content using HPLC (Waters, USA) as per Srinath et al. (2020, 2021). The semi quantitative RT-PCR was employed to evaluate the expression profile of ApHDR in different tissues of A. paniculata using actin as an internal control (Table 2) as per Srinath et al. (2020, 2021).

Results

PCR amplification and generation of ApHDR partial sequence

ApHDR internal fragments such as 750 and 800 bp were amplified using degenerative primers (Fig. 2). The Blast analysis showed the sequences were highly similar to other plants and an 1174 bp ApHDR gene sequence was obtained after aligning. The resultant partial sequence was submitted to GeneBank (NCBI accession number MH172444.1).

Fig. 2.

Amplified partial fragments of ApHDR using degenerative primers on agarose gel. L1: DNA marker L2: 750 bp, L3-800 bp, L4-750 bp

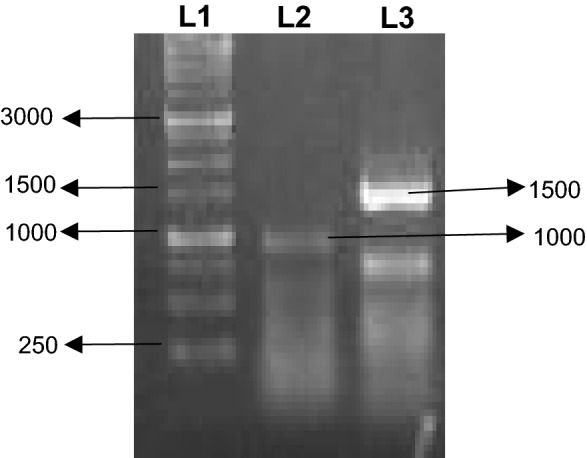

Isolation and cloning of full length ApHDR using 5′ and 3′ random amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) PCR

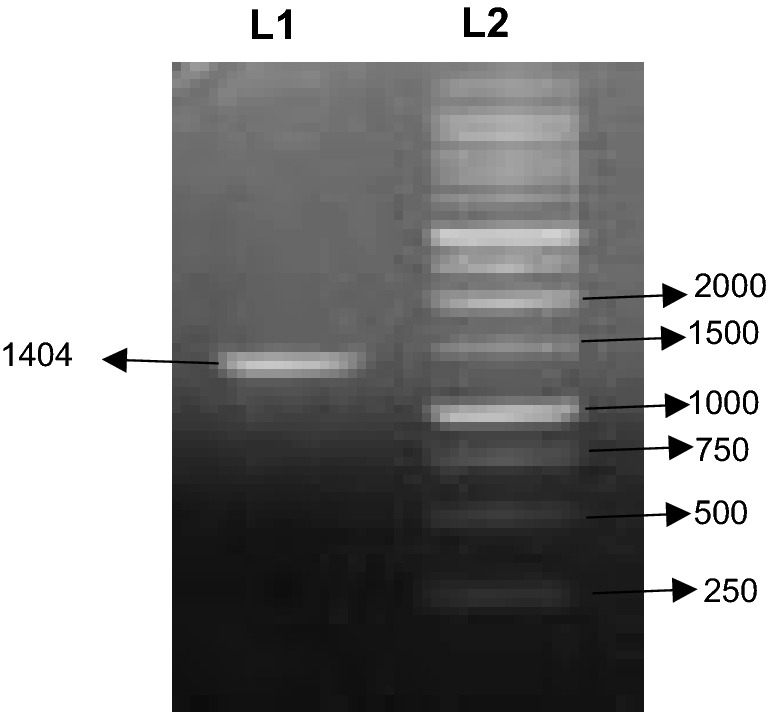

The 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR resulted in the amplification of 1000 bp and 1500 bp fragments, respectively (Fig. 3). The positive clones of E.coli cells containing recombinant plasmids were grown on antibiotic ampicillin medium. The both 5′ and 3′ RACE resulted in isolation of full length cDNA of ApHDR consisting of 1404 bp ORF (Fig. 4) with 100 bp 5′UTR and 235 bp 3′UTR. The full length gene sequence of ApHDR was submitted to NCBI with accession number MK503970.

Fig. 3.

Amplification of 5′ and 3′ RACE cDNA fragments of ApHDR. The cDNA was amplified using primers 5′ GSP and 3′GSP. Lane M represents Marker, L1- 5′ RACE fragment and L2 is 3′RACE fragment

Fig. 4.

Full length cDNA of ApHDR on 1% agarose gel. L1: Full length cDNA fragment of ApHDR (1404 bp). L2: DNA Marker

Cloning and heterologous expression of ApHDR

The full length ApHDR gene was successfully inserted into pET TOPO expression vector and transformed into E.coli BL 21 cells. The expression of recombinant protein was induced by IPTG in E. coli BL21 cells. An additional clear band at ~ 52 KD on SDS-PAGE gel was observed in which ApHDR protein band intensity was increased with duration of induction compared to control (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Qualitative analysis of total protein isolated from IPTG induced recombinant cells expressing ApHDR at 52 KD. L1: 0 hr un-induced L2: O hr induced L3:1 h induced L4: 3 hr induced L5:6 hr induced L6: Protein Marker

In silico bioinformatics analysis of ApHDR protein

Prediction of physicochemical properties

Physicochemical properties of ApHDR protein using Protparam of ExPASY proteomic server revealed that the predicted molecular weight was 52,292 dalton and isoelectric pI of 5.53. The other characteristic features such as formula, positively charged residues (Arg + Lys) and negatively charged residues (Asp + Glu), instability index, aliphatic indices and hydropathicity were given in the Table 4.

Table 4.

Physico chemical properties of the ApHDR prote in of A. paniculata

| Characteristic of the protein | Details |

|---|---|

| Number of aminoacids | 467 |

| Formula | C2310H3631N631O717S18 |

| Molecular weight | 52,292.12 daltons |

| Isoelectric point (pI) | 5.53 |

| Positively charged residues (Asp + Glu) | 66 |

| Negatively charged residues (Arg + Lys) | 54 |

| Instability Index | 28.67 |

| Aliphatic index | 80.11 |

| Grand average of hydropathicity | − 0.399 |

Sequence similarity search and prediction of conserved structural domain in ApHDR

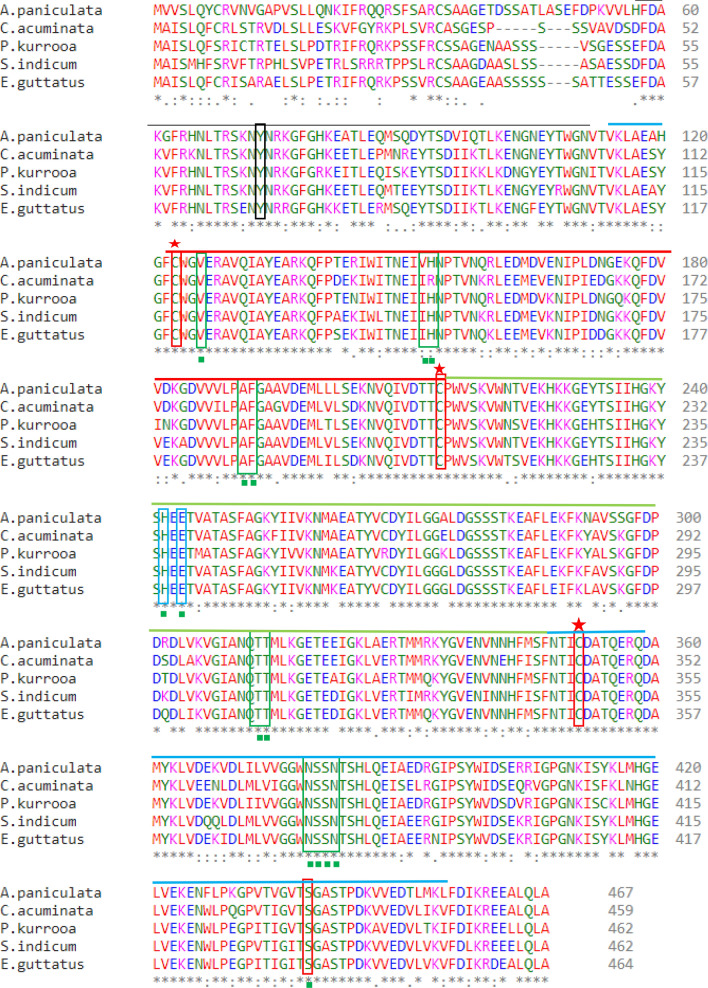

The BLAST search analysis revealed that ApHDR exhibited highest similarity with HDR of Sesamum indicum (82.44%identity) followed by Picrorhiza kurroa (82.01%), Erythranthe guttatus (81.37%) and Camptotheca acuminata (80.30%). NCBI-CD search revealed the presence of hydroxyl methyl butenyl diphosphate reductase conserved domain in ApHDR protein. This characteristic conserved domain belongs to LytB_Isph super family (Fig. 6). The conserved domain search also showed the presence of substrate binding site (chemical binding site), which was composed of 14 residues (V-126, V-152, H-153, A-191, F-192, H-242, E-244, T-313, T-314, NSSN- 379 to 382). The core catalytic site or active site embedded in substrate binding site composed of 4 residues i.e., H-242, E-244, S-380 and N-382 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Conserved domain search of putative ApHDR protein using NCBI-CD search indicating the protein is related to Lyt_IspH superfamily and three presence of different conserved sites (Fe-S cluster binding site, Substrate binding site, Catalytic site)

Fig. 7.

Multiple sequence alignment of ApHDR protein sequence with other plant HDRs i.e., Sesumum indicum, Erythranthe guttatus, Camptotheca acuminata, Picrorhiza kurroa. In figure Fe-S cluster binding site in ApHDR with three conserved ‘C’ residues indicated with ‘star’ above the sequence, Substrate binding site with 14 residues were indicted with ‘box’ below the sequence and catalytic site also with 4 residues embedded in substrate binding site only. ‘Y’ in black box is the conserved tyrosine residue at 73 position, which is essential for HDR function. Different colored lines above the sequences indicates: Black line- N terminal conserved region, Blue line- Domain 1, Red line- Domain2, Green line- Domain 3, Blue line- Domain 1 (repeated)

Secondary structure prediction

The secondary structure prediction of ApHDR protein was carried out using SOPMA server (Geourjon and Deleage 1995). The four conformational state helix, sheet, turn, coil were predicted which revealed that about 45.82% (214 amino acids) were involved in alpha helix formation, 16.27% (76 amino acids) involved extended strands, 6.42% (30 amino acids) involved in beta turn and about 31.48% (147 amino acids) were involved in random coil formation from total 467 amino acids (Fig. S1).

Prediction of subcellular localization and trans-membrane domain

A chloroplast transit peptide was found with 33 amino acids at the N-terminal of ApHDR using Chloro P. Target P – 2.0 also predicted it as a chloroplast transfer peptide. BaCelLo server showed that the localization of this protein is in chloroplast. TMHMM results predicted that there is no trans-membrane domains present in this protein which indicates that this protein might not be the secretory protein.

Homology modeling and structural validation of ApHDR

The 3-dimensional (3D) structure of ApHDR was generated using Phyre2 server with Plasmodium falciparum HDR (PfHDR) protein as the template. The model was constructed with 62% coverage (290 residues) and 100% confidence. The sequence identity with PfHDR was 29% (Fig. S2a). the homology modelling of ApHDR was also constructed using Swiss-Model server with a 31.06% sequence identity by using crystal structure of E. coli (3ke8.1A) as a template. The oligo state of protein was predicted as a homo dimer (Fig. S2b). Structural validation for models generated by Phyre2 and Swiss model was carried out by Ramachandran plot analysis using RAMPAGE web server. In the model generated by Phyre2 93.8% (285 amino acids) were present in favoured regions, 3.6% (11 amino acids) in allowed region and 2.6% (8 amino acids) in dis-allowed region (Fig. S3). However, in Swiss-Model generated structure, only 90% of amino acids were observed in the favoured regions. Hence, the model generated using Phyre2 was selected for further analysis. The Phyre2 Investigation results have also confirmed that the predicted model of ApHDR was structurally reliable (Fig. S4).

Structural view of ligand binding site prediction and phylogenetic analysis of ApHDR

The 3D Ligand Site prediction resulted in identification of the cluster with a total of 16 ligands with a confidence score of 100 (Fig. S5). The predicted binding site was composed of amino acid residues Trp (216), Val (217), Glu (244), Thr (313), Thr (314), Cys (351) and observed to have contact with 5 to 8 ligands in the proximity. The predicted structure using the structural library was reliable and can be used for protein interaction studies.

Phylogenetic tree was constructed to illustrate the evolutionary relationship of ApHDR with 31 other plant HDR sequences retrieved from GenBank (Fig. S6).The analysis showed that ApHDR closely related to Picrorhiza kurroa (Plantaginaceae family), Sesamum indicum (Pedaliaceae family) and Erythranthe guttatus (Phrymaceae family) among the order Lamiales.

Prediction of substrate and inhibitors interactions using in silico molecular docking studies

The substrate binding site and catalytic sites were shown to form the binding cleft for substrates and inhibitors for docking study in 3D view. It is evident from Rerank score that different substrate and inhibitory compounds showed variations in affinity of binding with the substrate binding cleft (Table 5). Among all compounds, Fe-S cluster showed highest affinity towards binding to its domain followed by substrate molecule HMBPP. ApHDR Fe-S cluster was shown to interact with three cysteine residues in its vicinity at positions (C123, C214, and C351).The selected inhibitors such as clomazone, paraquat and benzyl viologen have shown different binding affinities towards the substrate binding cleft. The clomazone and paraquat have showed similar binding affinity as the substrate molecule. Whereas, the compound benzyl viologen shown least affinity towards binding (Fig S7). The docking of ApHDR with its substrate HMBPP, Fe-S cluster and inhibitory compounds revealed the best orientation of the molecules when reacting with amino acids in the proximity. The interactions such as vanderwaals, electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds with the neighborhood amino acids depicted in 2D diagram (Fig S8).

Table 5.

MolDock algorithm aided docking of compounds in substrate binding cleft of ApHDR using Fe-S, HMBPP, Clomazone, Paraquat, Benzene viologen

| Compounds | MolDock score | Plants score | Rerank score | Internal score | H bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 124,886 (Fe-S) | − 81.9564 | − 55.1705 | − 89.7235 | 29.0921 | − 8.27745 |

| 5,281,976 (HMBPP) | − 71.8198 | − 48.9787 | − 64.7902 | 4.19636 | − 9.67549 |

| 54,778 (Clomazone) | − 75.0875 | − 57.1596 | − 61.0888 | 7.91241 | − 1.23204 |

| 15,939 (Paraquat) | − 67.4732 | − 62.8371 | − 58.0394 | 15.8018 | − 1.35429 |

| 14,196 (Benzylviologen) | − 95.7876 | − 32.9963 | − 37.8191 | 32.329 | − 1.67741 |

Estimation of andrographolide content in different plant parts

The andrographolide content in different plant parts of A. paniculata was analyzed using HPLC. The andrographolide content was observed as highest in young leaves (YL) with 5.89% (DW) followed by mature leaves (ML) with 4.2% (DW). In stem, the content was 1.782% (DW) and the least was observed in roots with 0.672% (DW) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Content of andrographolide in different plant parts of A. paniculata. RT- Roots, ST- Stem, ML-Mature leaves, YL-Young leaves

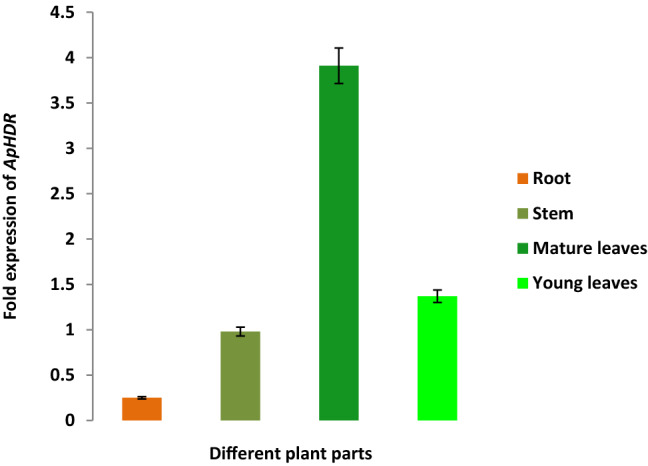

Differential gene expression profile of ApHDR in different plant parts

The differential gene expression analysis in different tissues of A. paniculata revealed that ApHDR was expressed in all tissues. The expression profile of ApHDR suggested a significant variation in the expression pattern among different tissues such as mature leaves, young leaves, stem and roots. A 16-fold higher expression of ApHDR was observed in the mature leaves of A. paniculata as compared to roots. Whereas young leaves and stem showed 5.5-fold and fourfold higher expression compared to roots of A. paniculata (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Relative ApHDR gene expression in different plant parts of A. paniculata. Roots, Stem, Matured leaves, Young leaves

Discussion

ApHDR gene a key regulatory enzyme in MEP pathway was successfully isolated, cloned from A. paniculata for the first time. In Camptotheca acuminate the gene size was1,377 bp (Wang et al. 2008) whereas, in Ginkgo biloba 1,422 bp (Kang et al. 2013). The HDR gene was 1389 bp in Isodon rubescens (Su et al. 2017) 1392 bp in Oncidium orchid (Huang et al. 2009) 1386 bp in Osmanthus fragrans (Xu et al. 2016) and 1389 bp in Salvia miltiorhiza (Hao et al. 2013). These studies on isolation and characterization of full length HDR gene from various plants reported the size of full length gene is in the range of 1,300 to 1,450 bp. Hence, the isolated ApHDR is full length and comparable to other plants’ HDR. The characteristic conserved domain belongs to LytB_Isph super family. Similar work has also been reported where isoprenoid biosynthesis via the methylerythritol phosphate pathway using the (E)‐4‐hydroxy‐3‐methylbut‐2‐enyl diphosphate reductase (LytB/IspH) from Escherichia coli (Wolff et al. 2003). The molecular cloning and characterization of the gene encoding 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidyl transferase from hairy roots of Rauvolfia verticillata was also investigated (Lan 2013).

The similar studies in secondary structure prediction were carried out in other plants where HDR physico chemical properties have close resemblance (Lv et al. 2015). This Fe-S cluster was observed to be conserved among Echerichia coli, Tripterygium wilfordii and other organisms (Hsieh et al 2014; Cheng et al 2017). It is a dioxygen-sensitive [4Fe-4S] cluster (Wolff et al. 2003) and play role in electron transport during oxidation–reduction reactions in chloroplast and might contribute for the MEP pathway regulation (Banerjee and Sharkey 2014). The secondary structure prediction will be important for residue conformational behaviors, hydrophobic movements, residue ratios and leads to further protein folding confirmations (Geourjon and Deleage 1995). Various reports in plants showed the presence of chloroplast transit peptide in HDR enzyme (Su X et al. 2017). The chloroplast transit peptide could play a role in transfer of protein from cytoplasm to chloroplast or interaction with lipid envelop and stromal processing peptidases (King and Sternberg 1996; Bruce 2000). The HDR 3-D structure in Huperzia serrate was also built using Plasmodium falciparum as the template (Lv et al. 2015). This homology modelling could serve as a basis for comprehensive discussion on catalytic pathway (Guevara-García 2005). The Ramachandran plot showed the accuracy of ApHDR protein model generated by Phyre2 was observed as more accurate compared to Swiss-Model.

The phylogenetic analysis showed that ApHDR closely related to Picrorhiza kurroa (Plantaginaceae family), Sesamum indicum (Pedaliaceae family) and Erythranthe guttatus (Phrymaceae family) among the order Lamiales. The present finding supported by observations from our previous studies in A. paniculata where the genes involved in terpenoid and other isoprenoids synthesis from MEP and MVA pathways were also shown to be closely related to Lamiales order. As the proteins perform their functions on ligands and regulated by them, the ligand binding site prediction could be useful for identification. These conserved cysteine residues were also found in other plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana and considered as crucial for Iron sulphur bridge formation (Hsieh et al. 2014).The Fe-S cluster will involve in the Fe-S bridge formation and a characteristic feature of most of the oxidoreductive enzymes (Uchida et al. 2018).

The present HPLC results are similar to previous reports where andrographolide production was highest in the young developmental stages and the leaves are the major contributors to the important diterpene lactone andrographolide, which is followed by stem and root tissues (Pandey and Mandal 2010; Srinath et al. 2020). The tissue-specific gene expression of ApHDR showed the prominent expression level in leaves compared to other tissues as the MEP pathway is mainly present in the plastids for the synthesis of diterpenoid lactone. The absence of MEP pathway and presence of the cytosolic MVA pathway in other plant parts such as stem and roots had led to the less and varied expression of the gene compared to leaves. This was consistent with the gene expression studies of HDR in other plants such as Rauvolfia verticillata, Artemisia annua. In Rauvolfia verticillata the gene expression study was conducted in different tissues such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits where the highest expression was observed in flowers followed by leaves and fruits. The least expression was seen in roots and stems Lu et al. (2008). In another report of R. verticillata the relative gene expression in different tissues such as root, stem, old leaf, young leaf, bark was conducted, among which the old leaf showed the highest HDR expression followed by bark and young leaves and root (Lan 2013). In Artemisia annua HDR expression pattern of different genes was studied in different tissues such as flower buds, young leaves, old leaves, stem and roots where HDR was expressed highly in flower buds followed by young leaves, old leaves, stem and roots (Ma et al. 2017). Various important secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, xanthones, phenylpropanoids and diterpene lactones were present in this plant (Cherukupalli et al 2016). The diterpene lactones, which are major bioactive constituents of this plant, were accumulated mainly in leaves compared to other plant parts (Garg et al. 2015). This indicated that the gene expression may depend on various other factors such as developmental stages of tissue. The study revealed the active role of HDR in MEP pathway which involves itself in the biosynthesis of IPP and DMAPP the vital precursors for andrographolide production. More studies are required to pinpoint the correlation of its tissue-specific expression with andrographolide biosynthesis which is helpful for understanding the active role of HDR in A. paniculata terpenoid pathway.

Conclusions

We have successfully isolated and cloned ApHDR, a rate limiting enzyme for the first time from A. paniculata. The phylogenetic analysis indicated the evolutionary relationship with closely related plants and their conserved domains which can be used for primer designing for isolation of key genes. In silico bioinformatics approaches and docking studies gave the structural and functional aspects of the enzyme ApHDR which could be helpful in identifying new targets for regulation of this light mediated MEP pathway. The correlation between the tissue specific expression pattern of ApHDR could be helpful in exploiting the genes for improved production of andrographolide indicating the important role of leaves in the MEP pathway. The present study has generated new information on genetic resources specifically HDR gene in A. paniculata for its manipulation and enhanced production of diterpene lactone andrographolide.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank DST-PURSE-II sponsored by Department of Science and Technology (DST) New Delhi, and OU-UGCCPEPA, UGC-BSR-RFSMS sponsored by University Grants Commission (UGC) New Delhi for financial support and fellowship to AS, MS, BBVB.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Humans and animals right

Authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any involvement of any human and/or animal participants.

Informed consent

Authors consented declare that they are having full knowledge and aware of the risks, benefits, and consequences of the molecular interventions using this plant material.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aayeti Shailaja, Email: shailaja.drp@gmail.com.

Mote Srinath, Email: srinath_mote@yahoo.com.

Byreddi Venkata Bhavani Bindu, Email: bindu167@gmail.com.

Charu Chandra Giri, Email: giriccin@yahoo.co.in.

References

- Altincicek B, Duin EC, Reichenberg A, Hedderich R, Kollas AK, Hintz M, Wagner S, Wiesner J, Beck E, Jomaa H. LytB protein catalyzes the terminal step of the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:437–440. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Sharkey TD. Methyl erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway metabolic regulation. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1043–1055. doi: 10.1039/C3NP70124G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Guti S, Kundu S, Das A, Das S, Mukherjee A. Oral andrographolide nanocrystals protect liver from paracetamol induced injury in mice. J Drug DelivSciTechnol. 2020;55:101406. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bindu BBV, Srinath M, Shailaja A, Giri CC. Proteome analysis and differential expression by JA driven elicitation in Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Wall. ex Nees using Q-TOF–LC–MS/MS. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2020;140:489–504. doi: 10.1007/s11240-019-01741-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Botella-Pavía P, Besumbes O, Phillips MA, Carretero-Paulet L, Boronat A, Rodríguez-Concepción M. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis in plants: evidence for a key role of hydroxyl methyl butenyl diphosphate reductase in controlling the supply of plastidial isoprenoid precursors. Plant J. 2004;40:188–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce BD. Chloroplast transit peptides: structure, function and evolution. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:440–447. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01833-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q, Tong Y, Wang Z, Su P, Gao W, Huang L. Molecular cloning and functional identification of a cDNA encoding 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase from Tripterygium wilfordii. Acta Pharm Sin. 2017;7:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherukupalli N, Divate M, Mittapelli SR, Khareedu VR, Vudem DR. De novo assembly of leaf transcriptome in the medicinal plant Andrographis paniculata. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1203. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ershov YV. 2-C-methylerythritol phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis as a target in identifying new antibiotics, herbicides, and immunomodulators: A review. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2007;43:115–138. doi: 10.1134/S0003683807020019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Agrawal L, Misra RC, Sharma S, Ghosh S. Andrographis paniculata transcriptome provides molecular insights into tissue-specific accumulation of medicinal diterpenes. BMC genomics. 2015;16:659. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1864-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geourjon C, Deleage G. SOPMA: significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Bioinformatics. 1995;11:681–684. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/11.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Dasgupta SC, Dasgupta AK, Gomes A, Gomes A. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) conjugated with andrographolide ameliorated viper (Daboia russellii russellii) venom-induced toxicities in animal model. J Nanosci. 2020;20:3404–3414. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2020.17421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräwert T, Rohdich F, Span I, Bacher A, Eisenreich W, Eppinger J, Groll M. Structure of active IspH enzyme from Escherichia coli provides mechanistic insights into substrate reduction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5756–5759. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-García A, San Román C, Arroyo A, Cortés ME, de la Luz G-N, León P. Characterization of the Arabidopsis clb6 mutant illustrates the importance of post transcriptional regulation of the methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway. Plant Cell. 2005;17:628–643. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao G, Shi R, Tao R, Fang Q, Jiang X, Ji H, Huang L. Cloning, molecular characterization and functional analysis of 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase (HDR) gene for diterpenoidtanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorhiza Bge. f. alba. Plant PhysiolBiochem. 2013;70:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland DR, Arnon DI. The water culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif Agric Exp Stn Circulation. 1938;347:32. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh WY, Sung TY, Wang HT, Hsieh MH. Functional evidence for the critical amino-terminal conserved domain and key amino acids of Arabidopsis 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:57–69. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.243642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JZ, Cheng TC, Wen PJ, Hsieh MH, Chen FC. Molecular characterization of the Oncidium orchid HDR gene encoding 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase, the last step of the methyl erythritol phosphate pathway. Plant cell rep. 2009;28:1475–1486. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandanur SGS, Kundu S, Cadena C, San Juan H, Bajaj A, Guzman JD, Golakoti NR. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new 12-substituted-14-deoxy-andrographolide derivatives as apoptosis inducers. Chem Pap. 2019;73:1669–1675. doi: 10.1007/s11696-019-00718-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MK, Nargis S, Kim SM, Kim SU. Distinct expression patterns of two Ginkgo biloba 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase/isopentenyldiphospahte synthase (HDR/IDS) promoters in Arabidopsis model. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;62:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJ. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:845. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RD, Sternberg MJ. Identification and application of the concepts important for accurate and reliable protein secondary structure prediction. Protein Sci. 1996;5:2298–2310. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Imtiaz M, Hussain A, Jalal F, Hayat S, Hussain S, Amir R. Isolation and functional characterization of an ethylene response factor (RhERF092) from rose (Rosa hybrida) Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2020;140:157–172. doi: 10.1007/s11240-019-01719-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. MolBiolEvol33:1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lan X. Molecular cloning and characterization of the gene encoding 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate cytidyltransferase from hairy roots of Rauvolfiaverticillata. Biologia. 2013;68:91–98. doi: 10.2478/s11756-012-0140-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Rujan T, Martin W, Croteau R. Isoprenoid biosynthesis: the evolution of two ancient and distinct pathways across genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:13172–13177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240454797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB, de Bakker PIW, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Structure validation by C alpha geometry: phi, psi and C beta deviation. Proteins. 2002;50:437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Wu W, Cao S, Zhao H, Zeng H, Tang LL, K, Molecular cloning and characterization of 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase gene from Ginkgo biloba. MolBiol Rep. 2008;35:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s11033-007-9101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H, Zhang X, Liao B, Liu W, He L, Song J, Chen S. Cloning and analysis of 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl-4-diphosphate reductase genes HsHDR1 and HsHDR2 in Huperzia serrate. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Li G, Zhu Y, Xie D-Y. Overexpression and Suppression of Artemisia annua 4-Hydroxy-3-Methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase 1 gene (AaHDR1) differentially regulate artemisinin and terpenoid biosynthesis front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:77. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Bo Y, Han L, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq R, Shahzad K, Shah ZH, Alsamadany H, Alzahrani HA, Alzahrani Y, Bashir A. Isolation of biotic stress resistance genes from cotton (Gossypium arboreum) and their analysis in model plant tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) for resistance against cotton leaf curl disease complex. J Virol Methods. 2020;276:113760. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthulakshmi V, Balaji M, Sundrarajan M. Biomedical applications of ionic liquid mediated samarium oxide nanoparticles by Andrographis paniculata leaves extract. Mater Chem Phys. 2020;242:122483. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neeraja C, Krishna PH, Reddy CS, Giri CC, Rao KV, Reddy VD. Distribution of Andrographis species in different districts of Andhra Pradesh. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad B Biol Sci. 2015;85:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s40011-014-0364-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Mandal AK. Variation in morphological characteristics and andrographolide content in Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Nees of Central India. Iranica J Energy Environ. 2010;1:165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratinam H, Nafi SNM. Andrographolide is an alternative treatment to overcome resistance in er-positive breast cancer via cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26:6. doi: 10.21315/mjms2019.26.5.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A. Elucidation of the methyl erythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoids biosynthesis in bacteria and plastids. A metabolic milestone achieved through genomics. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:1079–1089. doi: 10.1104/pp.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajeeb BK, Kumar U, Halder S, Bachar SC. Identification and quantification of Andrographolide from Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f.) Wall. ex Nees by RP-HPLC method and standardization of its market preparations. Dhaka Univ J Pharm Sci. 2015;14:71–78. doi: 10.3329/dujps.v14i1.23738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srinath M, Bindu BBV, Shailaja A, Giri CC. Isolation, characterization and in silico analysis of 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGR) gene from Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f) Nees. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:639–654. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-05172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinath M, Shailaja A, Bindu BBV, Giri CC. Molecular cloning and differential gene expression analysis of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS) in Andrographis paniculata (Burm. f) Nees. Mol Biotechnol. 2021;63:109–124. doi: 10.1007/s12033-020-00287-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N, Akhila A. Biosynthesis of andrographolide in Andrographis paniculata. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X, Yin L, Chen S. Molecular cloning and characterization of two key enzymes involved in the diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway of isodon rubescens. J Anal Bioanal Tech. 2017;8:2. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian R, Asmawi MZ, Sadikun A. A bitter plant with a sweet future? A comprehensive review of an oriental medicinal plant: andrographis paniculata. Phytochem Rev. 2012;11:39–75. doi: 10.1007/s11101-011-9219-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida H, Mizohata E, Okada S. Docking analysis of models for 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase and a ferredoxin from Botryococcusbraunii race B. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018;35:297–301. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.18.0601a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttekar MM, Das T, Pawar RS, Bhandari B, Menon V, Gupta SK, Bhat SV. Anti-HIV activity of semisynthetic derivatives of andrographolide and computational study of HIV-1 gp120 protein binding. Eur J Med. 2012;56:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Pi Y, Hou R, Jiang K, Huang Z, Hsieh MS, Tang K. Molecular cloning and characterization of 1-hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate reductase (CaHDR) from Camptotheca acuminata and its functional identification in Escherichia coli. BMB reports. 2008;41:112–118. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wass MN, Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ (2010) 3DLigandSite: predicting ligand-binding sites using similar structures.NAR 38: W469–73. PubMed. 10.1093/nar/gkq406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, Seemann M, Tse Sum Bui B, Frapart Y, Tritsch D, Estrabot AG, Rohmer M. Isoprenoid biosynthesis via the methylerythritol phosphate pathway: the (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase (LytB/IspH) from Escherichia coli is a [4Fe–4S] protein. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:115–120. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00317-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Li H, Yang X, Gu C, Mu H, Yue Y, Wang L. Cloning and expression analysis of MEP pathway enzyme-encoding genes in Osmanthusfragrans. Genes. 2016;7:78. doi: 10.3390/genes7100078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue L, He Z, Bi X, Xu W, Wei T, Wu S, Hu S. Transcriptomic profiling reveals MEP pathway contributing to ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:383. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziyuan L, Chunfei W, Jianjun Y, Xian L, Liangjun L, Libao C, Shuyan L. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of lotus salt-induced NnDREB2C, NnPIP1-2 and NnPIP2-1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-05156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.