Abstract

Background

Physical frailty phenotype is characterized by decreased physiologic reserve to stressors and associated with poor outcomes, such as delirium and mortality, that may result from post-kidney transplant (KT) inflammation. Despite a hypothesized underlying pro-inflammatory state, conventional measures of frailty typically do not incorporate inflammatory biomarkers directly. Among KT candidates and recipients, we evaluated the inclusion of inflammatory biomarkers with traditional physical frailty phenotype components.

Methods

Among 1154 KT candidates and recipients with measures of physical frailty phenotype and inflammation (interleukin 6 [IL6], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNFα], C-reactive protein [CRP]) at 2 transplant centers (2009–2017), we evaluated construct validity of inflammatory-frailty using latent class analysis. Inflammatory-frailty measures combined 5 physical frailty phenotype components plus the addition of an individual inflammatory biomarkers, separately (highest tertiles) as a sixth component. We then used Kaplan–Meier methods and adjusted Cox proportional hazards to assess post-KT mortality risk by inflammatory-frailty (n = 378); Harrell’s C-statistics assessed risk prediction (discrimination).

Results

Based on fit criteria, a 2-class solution (frail vs nonfrail) for inflammatory-frailty was the best-fitting model. Five-year survival (frail vs nonfrail) was: 81% versus 93% (IL6-frailty), 87% versus 89% (CRP-frailty), and 83% versus 91% (TNFα-frailty). Mortality was 2.07-fold higher for IL6-frail recipients (95% CI: 1.03–4.19, p = .04); there were no associations between the mortality and the other inflammatory-frailty indices (TNFα-frail: 1.88, 95% CI: 0.95–3.74, p = .07; CRP-frail: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.52–2.03, p = .95). However, none of the frailty-inflammatory indices (all C-statistics = 0.71) improved post-KT mortality risk prediction over the physical frailty phenotype (C-statistics = 0.70).

Conclusions

Measurement of IL6-frailty at transplantation can inform which patients should be targeted for pre-KT interventions. However, the traditional physical frailty phenotype is sufficient for post-KT mortality risk prediction.

Keywords: Frailty, Inflammation, Kidney transplantation, Validity

Frailty is characterized by a decreased physiologic reserve and distinct vulnerability to stressors (1). The physical frailty phenotype, the most widely used measure of frailty (2), was initially studied by Fried et al in community-dwelling older adults and includes unintentional weight loss, decreased grip strength, low physical activity, exhaustion, and slowed walking speed (1). Frailty has been well-described in adult patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and kidney transplant (KT) candidates (3–5). Frailty is applicable to ESKD patients of all ages (≥18 years) given that younger ESKD patients often experience accelerated aging compared to their healthy counterparts (6). This study of frailty to an adult population with kidney disease undergoing a surgical stressor that is a unique opportunity to better understand mechanisms of frailty. As we have previously demonstrated the restoration of kidney function improves frailty status in some but not all recipients (7). This suggests that frailty manifests as primary frailty, due to aging, and secondary frailty, resulting from ESKD in this population; this is consistent with what has been proposed among community-dwelling older adults (8).

Among ESKD and KT candidates, the physical frailty phenotype is associated with falls (9), hospitalizations (10–12), poor cognitive function (13), decreased health-related quality of life (14), lower access to KT (15), and mortality (10,12,16), regardless of age. Frailty has since been recognized as an important tool for risk prediction for KT recipients and candidates by transplant centers (17,18). Up to 20% of KT recipients of all ages are frail, and frailty is associated with poor outcomes after KT such as delirium (19), delayed graft function (20), longer length of stay (21), early hospital readmission (22), immunosuppression intolerance (23), lower health-related quality of life (24), and mortality (25). Many of these adverse outcomes have an underlying inflammatory component. Furthermore, the physical frailty phenotype includes self-reported components of frailty (exhaustion and activity) and may benefit from inclusion of objective laboratory values, such as inflammatory markers.

In community-dwelling older adults, elevated inflammatory markers, including interleukin 6 (IL6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and tumor necrosis factor-α receptor-1 (TNFα) are associated with frailty (26), which is a risk factor for mortality (27,28). Among older adults, frailty is more strongly associated with inflammatory markers than age highlighting their strong relationship (29). Additionally, chronic dialysis is associated increased inflammation (30), and inflammation is a risk factor for mortality in ESKD patients (31–33). Furthermore, inflammation and frailty are associated with increased risk of waitlist mortality in KT candidates, and the addition of inflammatory markers to the standard registry-based waitlist mortality model improves risk prediction (34). Thus, a measured index that combines frailty and inflammatory markers may be useful to identify KT candidates and recipients who are at an increased risk of mortality above and beyond the current risk prediction models. However, it is unclear whether the addition of inflammatory markers improves risk prediction for mortality in this novel population of adult KT recipients; measuring the 5 physical frailty components may be sufficient given the strong association between frailty and inflammation.

To better characterize frailty and inflammation among KT candidates and recipients, we sought to (i) determine if all 5 components were necessary for inclusion in the physical frailty phenotype (construct validity), (ii) identify underlying latent classes for physical frailty phenotype and inflammatory components, (iii) define a frailty-inflammatory index that combines the 5 components of the physical frailty phenotype and inflammatory biomarkers, (iv) quantify the association of a frailty-inflammatory index on post-KT mortality (predictive validity), and (v) test whether a frailty-inflammatory index improves post-KT mortality risk prediction above and beyond the physical frailty phenotype (predictive validity).

Method

Study Design

We leveraged a prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 1154 KT candidates and recipients with serum samples from Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, from 2009 to 2017 and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, from 2009 to 2016. Candidates were approached at KT evaluation and recipients were approached at admission for KT by trained research assistants. All eligible participants were enrolled; inclusion criteria at enrollment included (i) English-speaking and (ii) age 18 years or older. In this study, we collected blood samples and measured frailty at the time of KT evaluation for KT candidates or at the time of KT for KT recipients, as described below. Additional participant characteristics consistent with data collected in the national registry of transplant recipient (Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients) were also assessed at this time or abstracted from the transplant evaluation medical record (age, sex, race, ethnicity, cause of ESKD, blood type, body mass index, and time on dialysis). All participants with at least 3 out of 5 physical frailty phenotype components (below) and serum inflammatory markers were included in this analysis. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board and the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved the study. Physicians were not aware of the measured frailty scores or inflammatory maker levels at KT evaluation.

Frailty

We studied the physical frailty phenotype as defined (1) by Fried et al in older adults, validated among older women by Bandeen-Roche et al (35), and by our group in ESKD and KT populations (7,9,10,13–15,19–23,25,34,36–39). The phenotype was based on 5 components: shrinking (self-report of unintentional weight loss of more than 10 pounds in the past year based on dry weight); weakness (grip strength below an established cutoff based on gender and body mass index); exhaustion (self-report); low activity (kcals/week below an established cutoff); and slowed walking speed (walking time of 15 feet below an established cutoff by gender and height) (1). Each of the 5 components was scored as 0 or 1 representing the absence or presence of that component. The aggregate frailty score was calculated as the sum of the component scores (range 0–5); frailty was defined as a score of ≥3.

Inflammatory Markers

Serum inflammatory markers, IL6, TNFα, and CRP, were collected at KT evaluation and at admission for KT. A full description of inflammation measurements performed by our research group has been detailed elsewhere (34).

Latent Class Analysis

To evaluate construct validity of a frailty-inflammatory measure, we used latent class analysis (35). The hypothesis underlying latent class analysis is that underlying the population of KT candidates and recipients are discrete subpopulations characterized by sentinel patterns of physical frailty phenotype criteria and inflammatory biomarkers (35). Latent class analysis is used to identify: (i) a parsimonious set of distinct subgroups within the sample, (ii) the prevalence of each subgroup among the overall population, and (iii) the proportion that has each criterion among each subgroup. The aims of latent class analysis were to determine the number of subgroups or classes, prevalence of each subgroup in the overall sample, and the proportion of individuals who have a criterion for each subgroup (ie, the conditional probabilities given membership in a particular subgroup).

For this analysis we used the combined data of 1154 KT candidates and recipients to evaluate the optimal number of latent classes that fit the data using a series of latent class models. We estimated latent class analyses with 1, 2, 3, and 4 classes of the 5 components of the physical frailty phenotype alongside one of the inflammatory biomarkers (IL6, TNFα, or CRP). Latent class models for each biomarker were compared using goodness-of-fit statistics among models with different numbers of classes. We considered a variety of fit statistics and reported Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Additionally, we estimated the Lo-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio test, which tests the null hypothesis that a model solution with k classes provides no better fit than a model with k − 1 classes; a significant p value would suggest that an extra class is worthwhile. Additionally, we used a parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test to compare an k-class model solution with the (k − 1 )-class model solution. If frailty-inflammation is a syndrome, we hypothesized we would observe evidence for 2 or more classes, as a 1-class model indicates there are no distinguishable subgroups. Moreover, to meet the definition of a syndrome, we would hypothesize the conditional probabilities of class indicators need to increase uniformly or hierarchically with frailty severity (2).

Individuals were assigned to a latent class based on the highest posterior probability of class membership using the best-fitting model. We then used Cox proportional hazard models to examine the association between class membership and mortality.

Frailty-Inflammatory Index

We then tested the predictive validity of these newly identified frailty-inflammatory indices for post-KT mortality; we focused on KT recipients because they experience a common surgical stressor and because transplant centers are interested in using frailty for postsurgical risk prediction (17,18). For the 378 KT recipients, each frailty-inflammatory index combined the 5 components of Fried frailty plus an inflammatory marker (IL6, TNFα, and CRP). The highest tertile of each inflammatory marker (IL6 ≥ 7.1 pg/mL, TNFα ≥ 17 974 pg/mL, CRP ≥ 6.1 μg/mL) was counted as a point (40), in addition to the 5 point in Fried frailty index. For each new frailty-inflammatory index, ≥3 out of 6 points was considered frail as was established in the latent class analysis.

Mortality

For the 378 KT recipients, the Kaplan–Meier method was used to create unadjusted cumulative incidence curves of post-KT mortality by each frailty-inflammatory index score. Log-rank test of equality was used to test differences in unadjusted cumulative incidence curves. Cox proportional hazards model were used to calculate the risk of mortality by the frailty-inflammatory index, adjusting for age, sex, race, donor type (living versus deceased donor), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), cause of ESKD (hypertension, diabetes, cystic, glomerular), and smoking status. Proportional hazards assumptions were assessed by visual inspection of complementary log-log plots and Schoenfeld residuals.

Post-KT Mortality Prediction by Frailty and Markers of Inflammation

We then calculated the model discrimination using Harrell’s C-statistic, a measure of concordance indicating the model’s ability to distinguish (discriminate) between recipients with different times until post-KT mortality. The C-statistic ranges from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) and higher values indicate that the model more accurately predicts which patients will have longer survival. We tested whether the C-statistic improved over the base physical frailty phenotype model adjusting for age, sex, race, donor type, CCI, cause of ESKD, and smoking status, when we replaced the physical frailty phenotype with each frailty-inflammatory index score, separately; p values for the difference in C-statistics were estimated using the z-statistic.

Statistical Analyses

Comparison of candidate characteristics were performed using chi-squared test for categorical variables and t tests for normally distributed continuous variables or Wilcoxon rank sum for non-normally distributed continuous variables. All analyses were 2-tailed and α was set at a cutoff of 0.05. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.2/MP (College Station, TX) and MPlus (41).

Results

Study Population for Content Validity: KT Candidates and Recipients

Among the 1154 KT candidates, 378 (33.6%) underwent KT during the study period. The mean age was 54 (SD = 13) years, 34.3% were female, 42.2% were African American, and 219 (19.0%) were frail. The median (interquartile range) for IL6 was 4.4 (2.8–8.2) pg/mL, for TNFα was 11 985.1 (6815.2–19 309.6) pg/mL, and for CRP was 4.4 (1.8–9.9) μg/mL.

Study Population: KT Recipients

Among the 378 recipients, the average age was 53 (SD = 14) years, 34.1% were female, 43.1% were African American, and 14.9% were frail. The median (interquartile range) for IL6 was 4.6 (2.9–8.4) pg/mL, for TNFα was 14 325.4 (8202.4–20 130.8) pg/mL, and for CRP was 3.7 (1.6–7.9) μg/mL, which is comparable to the KT candidates. The distribution of IL6 (Supplementary Figure 1A), TNFα (Supplementary Figure 1B), and CRP μg/mL (Supplementary Figure 1C) are displayed among the KT recipients.

Latent Class Analysis

Based on fit criteria, a 2-class solution for the frailty-inflammatory index was considered the best model for each inflammatory marker that included shrinking, weakness, exhaustion, low activity, slowed walking speed, and the inflammatory marker. The Lo-Mendel-Rubin likelihood ratio test indicates the 2-class solution was better than the 1-class solution for each frailty-inflammatory index and Fried frailty (IL6-frailty p < .001, CRP-frailty p < .001, TNFα-frailty p < 0.001, Fried frailty p < .001) (Table 1). The preferred models were the 3-class model for Fried frailty and the 2-class model for the frailty-inflammatory indices. In other words, 2 classes (frail vs nonfrail) provided a better model fit than 3 classes (frail vs intermediate frail vs nonfrail) for models that included inflammatory markers; this implies that inclusion of these inflammatory markers is not ideal for identifying intermediate frail patients with ESKD.

Table 1.

Fit Indices for the Latent Class Analyses of the Frail-Inflammatory Models Among 1154 Kidney Transplant Candidates and Recipients

| Model Fit Statistics | 1-Class Model | 2-Class Model | 3-Class Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fried frailty | |||

| Lo-Mendel-Rubin* | NA | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| AIC | 7800 | 6619 | 6615 |

| BIC | 7835 | 6674 | 6701 |

| IL6-frailty | |||

| Lo-Mendel-Rubin* | NA | <0.001 | 0.1 |

| AIC | 8955 | 7733 | 7731 |

| BIC | 8995 | 7798 | 7832 |

| TNFα-frailty | |||

| Lo-Mendel-Rubin* | NA | <0.001 | 0.04 |

| AIC | 8955 | 7776 | 7774 |

| BIC | 8995 | 7841 | 7875 |

| CRP-frailty | |||

| Lo-Mendel-Rubin* | NA | <0.001 | 0.3 |

| AIC | 8954 | 7744 | 7743 |

| BIC | 8995 | 7810 | 7844 |

Notes: Based on the Lo-Mendel-Rubin test, there are at least 2 underlying classes within the Fried frailty phenotype and the frailty-inflammatory indices. By minimization of the BIC and Lo-Mendel-Rubin tests, we see that the 2-class model is a better fit for each frailty-inflammatory index. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; CRP = C-reactive protein; IL6: interleukin 6; NA = not applicable; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha.

*Use of parametric bootstrapped likelihood ratio test comparing 2-class to 3-class model: Fried frailty p = .03; IL6-fraity p = .2; TNFα-frailty p = .2; CRP-frailty p = .5.

When evaluating whether the 5 physical frailty phenotype components and inflammatory markers aggregated syndromically, we estimated the conditional probability of having each component and marker within the latent classes (Table 2). The results suggest that IL6 and CRP are as good as the 5 traditional components in separating out the classes. However, TNFα had the same conditional probability (20%) in both classes and is not contributing to the class separation and is unrelated to frailty class membership for TNFα-frailty. Despite the fact that TNFα was not discriminatory, we evaluated its criterion validity further against post-KT mortality for the sake of parallelism.

Table 2.

Conditional Probabilities and Prevalence of Frailty Components Among 1154 Kidney Transplant Candidates and Recipients

| Frailty Type | Prevalence, % | Class 1, Conditional Probability | Class 2, Conditional Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fried frailty | Frail | Nonfrail | |

| Walking speed | 14.9 | .29 | .06 |

| Grip strength | 36.7 | .62 | .20 |

| Weight loss | 17.5 | .24 | .13 |

| Exhaustion | 37.9 | .48 | .32 |

| Low physical activity | 43.8 | .65 | .30 |

| IL6-frailty | Frail | Nonfrail | |

| Walking speed | 14.9 | .30 | .05 |

| Grip strength | 36.7 | .61 | .21 |

| Weight loss | 17.5 | .24 | .13 |

| Exhaustion | 37.9 | .48 | .32 |

| Low physical activity | 43.8 | .65 | .31 |

| IL6 | 19.9 | .37 | .09 |

| TNFα-frailty | Frail | Nonfrail | |

| Walking speed | 14.9 | .29 | .06 |

| Grip strength | 36.7 | .63 | .20 |

| Weight loss | 17.5 | .24 | .13 |

| Exhaustion | 37.9 | .48 | .32 |

| Low physical activity | 43.8 | .65 | .30 |

| TNFα | 19.9 | .20 | .20 |

| CRP-frailty | Frail | Nonfrail | |

| Walking speed | 14.9 | .29 | .06 |

| Grip strength | 36.7 | .60 | .22 |

| Weight loss | 17.5 | .24 | .13 |

| Exhaustion | 37.9 | .48 | .31 |

| Low physical activity | 43.8 | .68 | .29 |

| CRP | 19.9 | .35 | .11 |

Notes: CRP = C-reactive protein; IL6 = interleukin 6; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha.

All participants who were classified as frail by the physical frailty phenotype were also classified as frail by IL6-frailty and 30.0% of those who were nonfrail were classified as frail by IL6-frailty (74% agreement; kappa = 0.40; p < .001). Similarly, CRP-frailty (74% agreement; kappa = 0.40; p < .001) and TNFα-frailty (76% agreement; kappa = 0.43; p < .001) had fair agreement (42) with the frailty classification by the physical frailty phenotype.

Frailty-Inflammatory index

Among the 378 KT recipients (Table 3), 14.5% were frail, 40.2% were IL6-frail, 38.1% were TNFα-frail, and 40.5% were CRP-frail (Supplementary Figure 2). Additionally, 35.7% were both IL6-frail and TNFα-frail, 36.5% were both IL6-frail and CRP-frail, and 34.4% were frail by all 3 frail-inflammatory indices. Among KT recipients who were not classified as frail by the physical frailty phenotype, 89 (23.5%) were newly classified as IL6-frail, 81 (21.4%) as TNFα-frail, and 90 (23.8%) as CRP-frail.

Table 3.

Demographics of 378 Kidney Transplant Recipients by Physical Frailty and IL6-Frailty Status

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 55 | N = 323 | N = 226 | N = 152 | |

| Physical Frailty | IL6-Frailty | |||

| Age* | 52.3 (14.2) | 56.1 (14.5) | 50.7 (13.9) | 56.1 (14.2) |

| Female, % | 35.0 | 29.1 | 33.2 | 35.5 |

| Race, % | ||||

| Caucasian | 48.6 | 50.9 | 48.7 | 49.3 |

| African American | 43.7 | 40.0 | 42.5 | 44.0 |

| Asian | 4.0 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 2.6 |

| Cause of ESKD, % | ||||

| Diabetes | 19.8 | 23.6 | 17.8 | 24.3 |

| Hypertension | 33.8 | 29.1 | 32.9 | 23.9 |

| Cystic | 10.2 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 11.8 |

| Glomerular | 24.5 | 27.3 | 26.7 | 22.4 |

| Charlson comorbidity index* | 1.5 (1.7) | 2.1 (1.9) | 1.4 (1.7) | 2.0 (1.8) |

| Living donor, % | 33.4 | 30.9 | 33.2 | 32.9 |

| Years on dialysis* | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Current smoker, % | 7.7 | 7.2 | 9.3 | 7.4 |

Notes: ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; IL6 = interleukin 6.

*Mean (standard deviation).

Association Between Each Frailty-Inflammatory Index and Post-KT Mortality

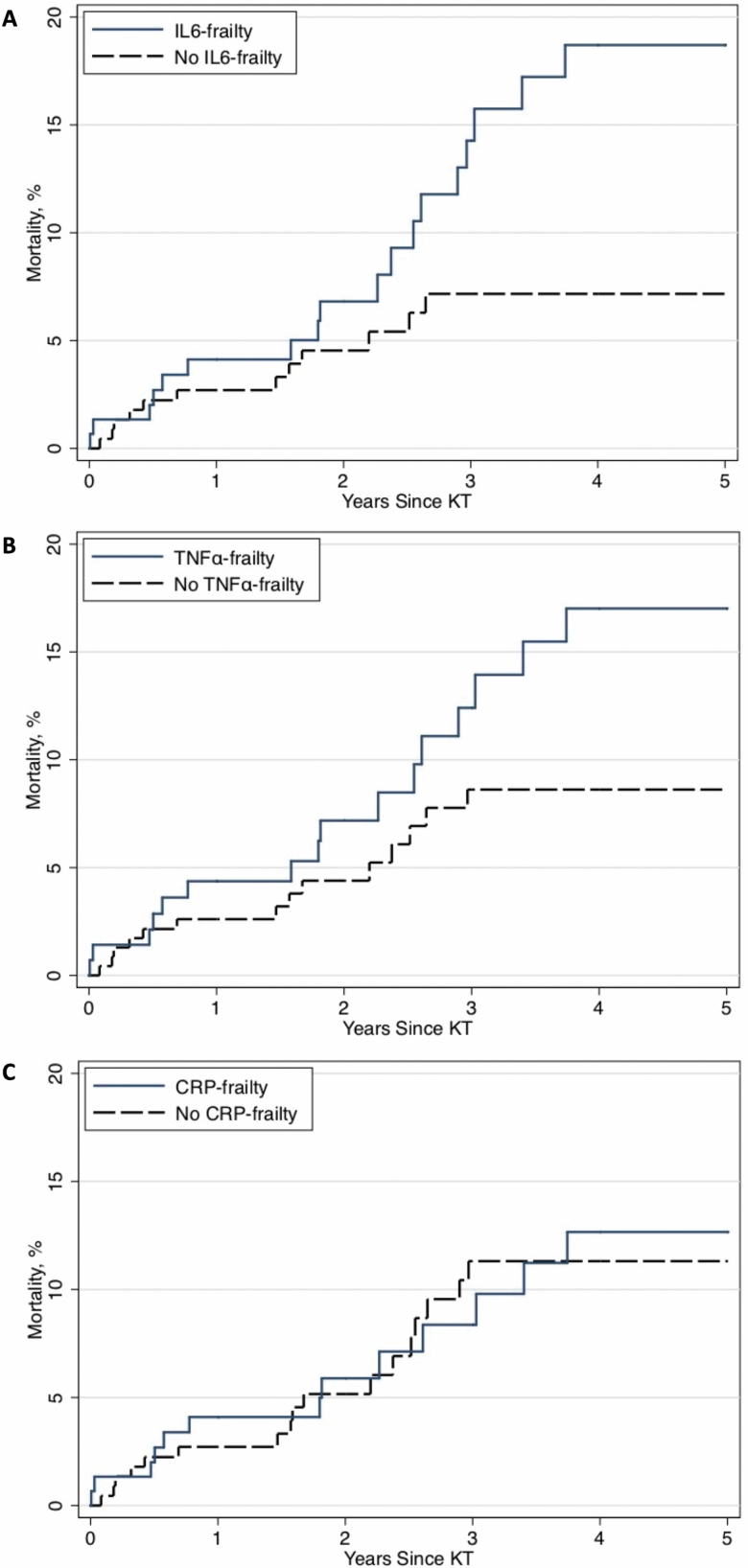

Mortality in IL6-frail KT recipients was higher than in IL6-nonfrail KT recipients (log-rank p = .01) (Figure 1A). The cumulative incidence of post-KT mortality for IL6-frail versus IL6-nonfrail KT recipients was 4.1% versus 2.7% at 1 year, 14.3% versus 7.2% at 3 years, and 18.7% versus 7.2% at 5 years following KT. After adjustment for recipient age, sex, CCI, race, cause of ESKD, and living donor, IL6-frail KT recipients had a 2-fold higher risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.03–4.19, p = .04) compared to IL6-nonfrail KT recipients (Table 4). Kidney transplant recipients with IL6-frailty were more likely to be older (mean age = 56 vs 50.7, p < .001), and had a higher CCI score (mean score = 2.0 vs 1.4, p < .001) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of mortality after kidney transplantation (KT) for each frailty-inflammatory index: (A) interleukin 6 (IL6), (B) tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and (C) C-reactive protein (CRP) among 378 KT recipients.

Table 4.

Risk of Post-Kidney Transplant (KT) Mortality by Physical Frailty Phenotype and Inflammatory-Frailty Indices Among 378 KT Recipients

| Frailty Model | Mortality Risk | p Value | C-Statistic | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base physical* frailty phenotype model | NA | NA | 0.70 | † |

| IL6-frailty | 2.07 (1.03–4.19) | p = .04 | 0.71 | .47 |

| TNFα-frailty | 1.88 (0.95–3.74) | p = .07 | 0.71 | .56 |

| CRP-frailty | 1.02 (0.52–2.03) | p = .95 | 0.71 | .19 |

Notes: CRP = C-reactive protein; ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; IL6 = interleukin 6; NA = not applicable; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha.

*Frailty, age, sex, race, donor type, Charlson comorbidity index, cause of ESKD, and smoking status.

†Reference for C-statistic p value.

Mortality in TNFα-frail KT recipients was higher than in TNFα-nonfrail KT recipients (log-rank p = .04) (Figure 1B). The cumulative incidence of post-KT mortality for TNFα-frail versus TNFα-nonfrail KT recipients was 4.4% versus 2.6% at 1 year, 12.4% versus 8.6% at 3 years, and 17.0% versus 8.6% at 5 years following KT. However, after adjustment for recipient age, sex, CCI, race, cause of ESKD, and living donor, TNFα-frail KT recipients had a statistically insignificant difference in the risk of mortality compared to TNFα-nonfrail KT recipients (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.88, 95% CI: 0.95–3.74, p = .07) (Table 4).

Mortality in CRP-frail KT recipients was similar to CRP-nonfrail KT recipients (log-rank p = .5) (Figure 1C). The cumulative incidence of post-KT mortality for CRP-frail versus CRP-nonfrail KT recipients was 4.1% versus 2.7% at 1 year, 8.4% versus 11.3% at 3 years, and 12.7% versus 11.3% at 5 years following KT. After adjustment for recipient age, sex, CCI, race, cause of ESKD, and living donor, CRP-frail KT recipients had a similar risk of mortality compared to CRP-nonfrail KT recipients (adjusted hazard ratio: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.52–2.03, p = .95) (Table 4).

Post-KT Mortality Prediction by Frailty and Each Frailty-Inflammatory Index

The C-statistic for the model with physical frailty phenotype was 0.70 (Table 4). Replacing the physical frailty phenotype with IL6-frailty (C-statistic = 0.71; p = .47), TNFα-frailty (C-statistic = 0.71; p = .56), or CRP-frailty (C-statistic = 0.71; p = .19) did not improve post-KT mortality risk prediction (Table 4).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of frailty and inflammation in 1154 KT candidates and recipients, we identified 2 underlying classes (frail vs nonfrail) with the addition of 1 inflammatory marker to the physical frailty phenotype components; however, 3 classes were identified for physical frailty phenotype. We found up to 40% of KT recipients had IL6-frailty which was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of post-KT mortality. Notably, IL6-frailty was the only frailty-inflammatory marker that was associated with an increased risk of post-KT mortality. However, IL6-frailty (C-statistic = 0.71) did not improve post-KT mortality risk prediction above and beyond the physical frailty phenotype (C-statistic = 0.70).

While the number of underlying latent classes of the physical frailty phenotype has been identified among community-dwelling older women (35), this is the first study to test the construct validity of frailty among KT candidates and recipients. Like the previous study among community-dwelling older women, we found that both the 2- and 3-class solution were better than the 1-class model, suggesting that there are underlying subpopulations present. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that there is aggregation in the 5 traditional components and support construct validity (8). Furthermore, we expanded the study of frailty in KT recipients and we found 2 underlying latent classes of frailty-inflammation in KT candidates and recipients. This is an important step to confirm underlying frailty-inflammatory classes exist; to our knowledge this is the first evaluation of a frailty-inflammatory phenotype that combines the 5 physical frailty phenotype components with measured inflammatory markers. These findings are novel and help to further our understanding of frailty.

Our finding that IL6-frailty was associated with an increased risk of mortality in KT recipients is similar to prior studies that showed an association between elevated IL6 levels with cardiovascular events, graft loss, and mortality in KT recipients (40,43,44). We extended these findings by combining the physical frailty phenotype parameters and inflammatory biomarkers. The physical frailty phenotype captures the reduced physiologic reserve, which manifests as a resistance to stressors in patients, and thus likely provides a more complete picture of a patient’s true physical reserve compared to a single laboratory value. However, each frailty-inflammatory index did not improve the discrimination beyond the physical frailty phenotype. This suggests that there is little, if any, added risk prediction achieved by additionally measuring IL6 or any other inflammatory biomarker. These findings are important for clinical care as they suggest that measuring the 5 physical frailty components is sufficient; there is no added predictive value of also measuring inflammatory markers. Given the resources necessary for taking a blood draw, processing, and analyzing these blood samples, these findings have important implications for the evaluation and management of KT recipients.

This study has several notable strengths including a large prospective cohort of KT candidates and recipients, inclusion of 2 transplant centers, and measurement of novel parameters, frailty, and inflammatory biomarkers, not available in national registry data. This study sample is novel in that it assesses frailty in adults of all ages with ESKD. Furthermore, this is the only study to address the construct validity of the physical frailty phenotype among patients with ESKD of all ages. One limitation is the 2-center study design, making it difficult to generalize results to centers with different study populations. Additionally, the inflammatory markers were collected during routine bloodwork, so variations due to hemodialysis, hospitalizations, infection, or medication use may be present.

In conclusion, we identified a novel frailty-inflammatory index that includes components from the physical frailty phenotype and the inflammatory marker, IL6, in KT candidates and recipients; indices incorporating other inflammatory markers (CRP, TNFα) were not as promising in this population. Kidney transplant recipients with IL6-frailty were more likely to be older and have a higher comorbidity burden. Additionally, after adjustment for recipient, donor, and transplant factors, KT recipients with IL6-frailty are at nearly a 2-fold increased risk of mortality. Identification of frail patients with IL6-frailty captures a larger proportion of the population and could be useful to help identify KT candidates who would benefit from exercise interventions (45) like prehabilitation (46). However, if the goal of measuring frailty is to simply improve post-KT morality risk prediction, then measuring the 5 components of the physical frailty phenotype is sufficient.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute of Aging: grant numbers F32AG053025 to C.E.H., K24DK101828 to D.L.S., R01AG055781 to M.M.-D., R01DK114074 to M.M.-D., and P30AG021334 to K. Bandeen-Roche.

Conflict of Interest

No authors report a conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the writing of the manuscript. A.G. and C.E.H. are responsible for the data analysis.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buta BJ, Walston JD, Godino JG, et al. Frailty assessment instruments: systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;26:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sy J, Johansen KL. The impact of frailty on outcomes in dialysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26:537–542. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haugen CE, Thomas AG, Chu NM, et al. Prevalence of frailty among kidney transplant candidates and recipients in the United States: estimates from a National Registry and Multicenter Cohort Study. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(4):1170–1180. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Chu NM, Segev DL. Frailty and long-term post-kidney transplant outcomes. Curr Transplant Rep. 2019;6:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s40472-019-0231-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chu N, Chen X, Norman S, et al. Frailty prevalence in younger ESKD patients undergoing dialysis and transplantation. Am J Nephrol. 2020;1–10. doi: 10.1159/000508576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Isaacs K, Darko L, et al. Changes in frailty after kidney transplantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2152–2157. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bandeen-Roche K, Gross AL, Varadhan R, et al. Principles and issues for physical frailty measurement and its clinical application. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(6):1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Suresh S, Law A, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:896–901. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Delgado C, et al. Factors associated with frailty and its trajectory among patients on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(7):1100–1108. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12131116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bao Y, Dalrymple L, Chertow GM, Kaysen GA, Johansen KL. Frailty, dialysis initiation, and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1071–1077. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2181–2189. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01960215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Olorundare I, et al. Frailty and health-related quality of life in end stage renal disease patients of all ages. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5:174–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haugen CE, Chu NM, Ying H, et al. Frailty and access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:576–582. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12921118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johansen KL, Dalrymple LS, Glidden D, et al. Association of performance-based and self-reported function-based definitions of frailty with mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:626–632. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03710415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Chu NM, et al. ; AST Kidney Pancreas Community of Practice Workgroup . Perceptions and practices regarding frailty in kidney transplantation: results of a national survey. Transplantation. 2019;104(2):349–356. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kobashigawa J, Dadhania D, Bhorade S, et al. Report from the American Society of transplantation on frailty in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(4):984–994. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15198.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haugen CE, Mountford A, Warsame F, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and sequelae of post-kidney transplant delirium. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1752–1759. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018010064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garonzik-Wang JM, Govindan P, Grinnan JW, et al. Frailty and delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg. 2012;147:190–193. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McAdams-DeMarco MA, King EA, Luo X, et al. Frailty, length of stay, and mortality in kidney transplant recipients: a national registry and prospective cohort study. Annals of Surgery. 2017;266(6):1084–1090. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2091–2095. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Tan J, et al. Frailty, mycophenolate reduction, and graft loss in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2015;99:805–810. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Olorundare IO, Ying H, et al. Frailty and postkidney transplant health-related quality of life. Transplantation. 2018;102:291–299. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, King E, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:149–154. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yao X, Li H, Leng SX. Inflammation and immune system alterations in frailty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brinkley TE, Leng X, Miller ME, et al. Chronic inflammation is associated with low physical function in older adults across multiple comorbidities. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:455–461. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Varadhan R, Yao W, Matteini A, et al. Simple biologically informed inflammatory index of two serum cytokines predicts 10 year all-cause mortality in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:165–173. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van Epps P, Oswald D, Higgins PA, et al. Frailty has a stronger association with inflammation than age in older veterans. Immun Ageing. 2016;13:27. doi: 10.1186/s12979-016-0082-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kooman JP, Dekker MJ, Usvyat LA, et al. Inflammation and premature aging in advanced chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;313:F938–F950. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00256.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yeun JY, Levine RA, Mantadilok V, Kaysen GA. C-reactive protein predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70200-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zimmermann J, Herrlinger S, Pruy A, Metzger T, Wanner C. Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:648–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wetmore JB, Lovett DH, Hung AM, et al. Associations of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A with mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2008;13:593–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01021.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Thomas AG, et al. Frailty, inflammatory markers, and waitlist mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease in a prospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2018;102:1740–1746. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–266. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Olorundare I, et al. Individual frailty components and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101(9):2126–2132. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chu NM, Gross AL, Shaffer AA, et al. Frailty and changes in cognitive function after kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:336–345. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018070726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chu NM, Deng A, Ying H, et al. Dynamic frailty before kidney transplantation-time of measurement matters. Transplantation. 2019;103(8):1700–1704. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pérez Fernández M, Martínez Miguel P, Ying H, et al. Comorbidity, frailty, and waitlist mortality among kidney transplant candidates of all ages. Am J Nephrol. 2019;49:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000496061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Molnar MZ, Nagy K, Remport A, et al. Inflammatory markers and outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101:2152–2164. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muthén LK, Muthén BO.. Mplus User’s Guide: Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abedini S, Holme I, März W, et al. ; ALERT study group . Inflammation in renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1246–1254. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00930209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dahle DO, Mjøen G, Oqvist B, et al. Inflammation-associated graft loss in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:3756–3761. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang CJ, Johansen KL. Are dialysis patients too frail to exercise? Semin Dial. 2019;32:291–296. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Van Pilsum Rasmussen S, et al. Prehabilitation prior to kidney transplantation: results from a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13450. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.