Abstract

Background

Clinically assisted hydration (CAH) can be provided in the last days of life as drinking declines. The impact of this practice on quality of life or survival in the last days of life is unclear. Practice varies worldwide concerning this emotive issue.

Method

Systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of studies evaluating the impact of, or attitudes toward, CAH in the last days of life. Databases were searched up to December 2019. Studies were included if the majority of participants were in the last 7 days of life, and were evaluated using Gough’s 'Weight of Evidence' framework. Review protocol registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42019125837.

Results

Fifteen studies were included in the synthesis. None were judged to be both of high quality and relevance. No evidence was found that the provision of CAH has an impact on symptoms or survival. Patient and family carer attitudes toward assisted hydration were diverse.

Conclusion

There is currently insufficient evidence to draw firm conclusions on the impact of CAH in the last days of life. Future research needs to focus on patients specifically in the last days of life, include those with non-malignant diagnoses, and evaluate best ways to communicate effectively about this complex topic with patients and their families.

Keywords: end of life care, terminal care, delirium, prognosis, clinical decisions

Introduction

Expected deaths tend to be characterised by a preceding period of reduced consciousness alongside reduction or cessation of oral intake.1–3 When drinking diminishes, clinically assisted hydration (CAH) can be commenced, involving medical administration of fluid via an intravenous or subcutaneous route.1 However, questions about the value of CAH in the last days of life are contentious, emotive and currently unanswered: practice varies considerably between individual clinicians, settings and countries.

Many patients, family carers, healthcare professionals (HCPs) and members of the public have expressed the view that CAH should be given routinely near the end of life. A review of the Liverpool Care Pathway in the UK found that relatives were concerned that withholding CAH had led to dehydration that accelerated the dying process.4 The belief that dehydration is distressing for dying patients is associated with high levels of emotional distress for bereaved relatives.5 HCPs also report concern at the prospect of withholding CAH,6 fearing the potential for dehydration to worsen symptoms including delirium, fatigue and thirst.7

Conversely, routine provision of CAH in the last days of life is often not supported by HCPs experienced in providing end-of-life care. CAH can be considered as hindering a ‘natural’ death, with hydration viewed as having the potential to increase nausea, dyspnoea, cough, respiratory secretions and the need to urinate.7 No literature describes similar concerns from the public.

These opposing views frequently result in differences of opinion between HCPs and those in need of their services. Practice varies markedly between individuals, between healthcare organisations and across cultures, with a striking lack of consensus. One review noted a broad range of 10%–88% of patients with cancer receiving CAH in the last week of life8; in another, 22%–100% of HCPs preferred providing CAH at the end of life, whereas 1%–75% preferred not to.7 Demonstrating the impact of cultural norms on practice in this field, a Dutch study found 74% of dying hospitalised patients received intravenous hydration, compared with 2% of dying hospice patients.9 A Delphi study defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia found high or very high consensus for 51 out of 57 domains but only moderate consensus around the statement ‘Hydration… is inappropriate in the dying phase’.10 Clinical guidance is also vague; UK guidelines state that hydration decisions should be ‘individualised’, but provide little specific information.11

Decisions about CAH can have broader implications, including impact on the place of the death. Although home is often the preferred place,12 in many countries parenteral hydration is not available in the home setting. The UK’s comprehensive District Nursing Manual of Clinical Procedures does not mention home hydration.13 A decision to provide CAH, therefore, has the potential to prevent a patient from dying at home.

Five systematic reviews have evaluated CAH near the end of life, the most recent published in 2014. Two reviews investigated attitudes,7 14 one modes of CAH delivery,15 and another CAH in palliative care patients.16 These revealed a lack of research, with limited evidence of benefit. Only one focused on CAH at the very end of life; Raijmakers et al’s review of CAH in the last week of life of patients with cancer found little benefit from this practice.8

Evaluation of CAH in the last days of life is particularly important, as this is the point when drinking tends to diminish rapidly and clinical decision-making can be particularly challenging. A systematic review is, therefore, needed that focuses on the impact of CAH in the last days of life, while allowing broad eligibility in relation to study design and participants, in order to provide a comprehensive updated appraisal of this clinically relevant and emotive topic.

Review aims

To undertake a systematic review of literature evaluating the impact of CAH in the last days of life on symptoms and survival, and the attitudes of patients and family carers with direct experience of this practice.

Methods

An information specialist (IK) developed a search strategy that was adapted for each database searched: Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO all via EBSCO, Embase via OVID, Web of Science Core Collection, the Cochrane Library, ASSIA via Proquest and AMED via NHS HDAS. Box 1 displays the search strategy used for Medline. Searches were conducted of the literature up to December 2019. Reference searches, citation searches and electronic searches of relevant journals (Palliative Medicine, Journal of Clinical Oncology, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care) were also undertaken.

Box 1. Medline search strategy.

((MH “Terminal Care+“) OR (MH “Terminally |||+“) OR (“end of life” or “end-of—Iife” or terminal-stage* or terminal- phase* or (terminal* N3 (stage* or phase* or ill*)) OR ((last or final) N3 (day* or week* or month*)) OR (“end- stage disease*” or “end stage disease*” or “end-stage illness*” or “end stage illness”) OR ((“less than” N3 (week* or month*)) and (death or die or dying or life or live* or died)))

AND

((fluid* N6 (balanc* or therap* or manag*)) OR (hydrat* or dehydrat* or rehydrat*) OR (MH “Fluid Therapy+“) OR (MH “Dehydration”))

Abstract screening was conducted independently by AK and GC after exclusion of duplicate or irrelevant titles, with any disagreements between reviewers being resolved by consensus. AK obtained the full text of potentially relevant articles. AK and RB assessed their eligibility (box 2), extracted data and independently graded the articles by Gough’s Weight of Evidence (WoE) framework (box 3).17 This framework was considered well suited to this review given its emphasis on studies’ relevance to the review’s questions, as well their quality, along with its flexibility in allowing appraisal of studies with a wide range of methodology.18 Disagreements were resolved by discussion to gain consensus.

Box 2. Eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Published papers or abstracts presenting empirical research relating to clinically assisted hydration (CAH)

Study population in the last days of life (mean/median survival <7 days; if average survival data not reported, evidence that the majority of participants were in the last 7 days of life)

Any geographic location and any setting (hospital, hospice, nursing home or home)

-

Research that assesses one or more of:

Symptoms of patients with or without CAH

Survival of patients with or without CAH

Attitudes towards CAH of patients in last days of life, and/or of their relatives (contemporaneous or when bereaved)

Exclusion criteria

Case series or case reports

Papers not in English language

Children (aged 17 years or under)

Grey literature

Research with no new empirical data (opinion papers, editorials, literature reviews)

-

Research that assesses:

Attitudes towards CAH of healthcare professional, the general public or patients not in the last days of life

Withdrawal of CAH already being given, for example, for patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness

The enteral route, for example, fluids via nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Artificial nutrition only

Box 3. Quality appraisal using Gough’s Weight of Evidence (WoE).

For this review’s assessment using WoE framework, papers were assigned scores of low, medium or high in the three domains A, B and C, as well as the composite fourth domain, D.

WoE A: Judged against the internal validity of included studies, that is, study rigour, transparency and repeatability of method, quality of description of results, accurate analysis, and whether conclusions were justified from methods and results.

WoE B: Judged on the appropriateness of the study design in relation to the review‘s questions. Regarding this review’s primary question, study designs were rated more highly if they were better suited to demonstrating potential causal links between provision or withholding of clinically assisted hydration and the development of symptoms.

WoE C: Judged on the relevance of included studies regarding the review’s questions. Studies were rated more highly if the included participants were in the last week of life and if relevant outcome measures were used.

WoE D: The above three judgements are combined to form an overall assessment of the extent to which a study lends evidence toward answering the review questions.

Review-specific criteria adapted from Gough.17

AK conducted a narrative synthesis, given the utility of this approach when synthesising evidence from both qualitative and quantitative studies.19 Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneous methodology and outcome measures. The narrative synthesis involved three stages. Initially, a preliminary textual synthesis of each study was created, followed by inductive thematic analysis, using variable labels as themes. Second, to explore relationships within the data, AK compared data within and across studies, including a process of investigator triangulation that considered similarities and differences in methodological approaches between studies. Finally, the robustness of the synthesis was assessed. Articles of low Gough’s WoE rating were included to increase the breadth of the review and reveal areas without any research evidence, but were given less weight in the synthesis and discussion.

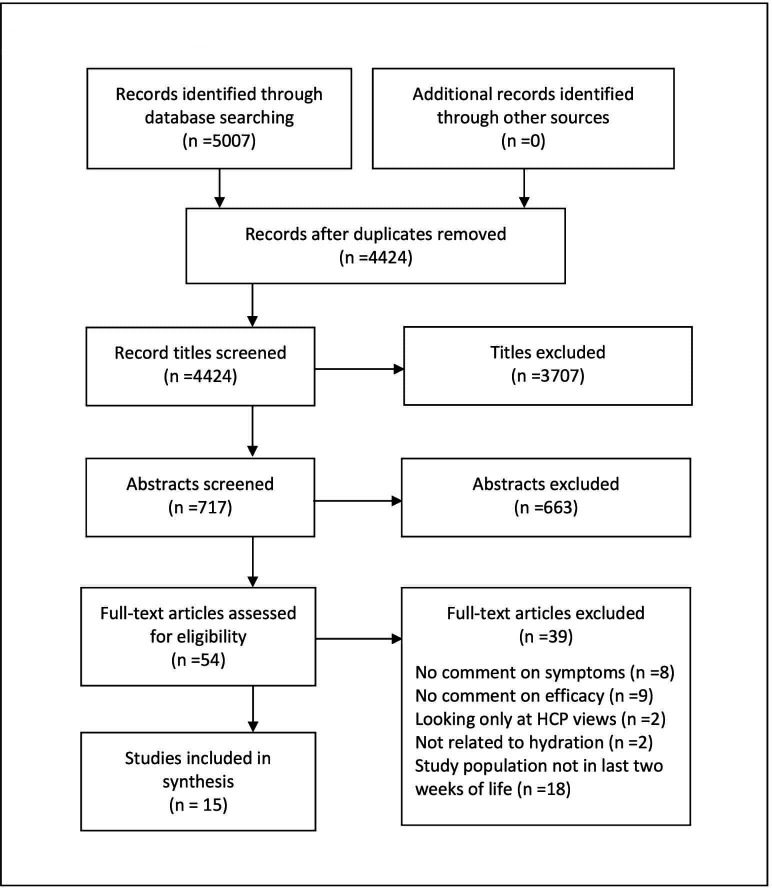

Database searches identified 4424 titles after deduplication. After screening 717 abstracts, 15 studies were judged to meet inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis (figure 1). No additional eligible studies were found from the reference, citation and specific journal searches.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. HCP, healthcare professional.

The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42019125837): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=125837.

Results

The fifteen included studies were described in twelve peer-reviewed journal papers, one MSc thesis and two published abstracts. Using Gough’s framework, eight studies were judged to provide ‘medium’ and seven ‘low’ WoE. One trial was well designed and of high quality, but was rated ‘medium’, as it was a feasibility study without the design or power to provide definitive outcomes.20

The synthesis included data from 2327 patients and 131 family caregivers. Dates of publication ranged from 1995 to 2019, and studies were conducted in several continents: Asia (eight studies), Europe (three), North America (two), Oceania (one) and South America (one). Three studies reported data collected from inpatient participants in palliative care units or hospices; six hospital-based data, three from mixed locations and three were unclear. The majority of studies (13 of 15) recruited only patients with cancer. Online supplemental table 1 provides a summary of included studies.

bmjspcare-2020-002600supp001.pdf (122KB, pdf)

Symptoms

Excess respiratory secretions (n=8)

CAH was not associated with severity of respiratory secretions in six of eight studies.9 20–25 Two, providing medium23 and low25 WoE, respectively, found secretions to be worse in the group that received more hydration.

Agitation (n=6)

The terms ‘agitation’, ‘delirium’ and ‘restlessness’ were frequently used interchangeably. A feasibility trial found an unchanged incidence of delirium, although its onset was delayed in the group receiving hydration.20 Four small low WoE studies found no impact from CAH.22 23 26 27 An observational study showed no association between terminal restlessness and volume of fluid intake overall, but did see a significant association between higher fluid intake in the final 25–40 hours, and worse restlessness in the 24 hours preceding death.9

Nausea (n=5)

Four studies found no impact of CAH on nausea when compared with usual care.20 21 24 28 One small prospective trial found better relief from nausea at 48 hours in the hydration group.26

Breathlessness (n=4)

CAH had no impact on the severity of breathlessness in three studies.20 25 28 A retrospective observational study of medical records found an association between breathlessness severity and administration of higher fluid volumes near the end of life21

Oedema/fluid overload (n=4)

Three of four studies found no impact of CAH on the incidence or severity of peripheral oedema.22 25 28 One small observational study noted worse oedema in a group receiving higher volumes of hydration.23 Pleural effusion severity was not influenced by the use of CAH,22 23 but two of three studies found CAH to be associated with worsening ascites.22–24

Thirst or dry mouth (n=3)

None of the three studies, all published 20 or more years ago, demonstrated any impact of CAH on the experience of thirst.26 28 29 These studies did not draw distinctions between reporting of thirst and dry mouth, or comment on use of measures to hydrate the oral cavity.

Other symptoms

No impact of CAH was found in relation to pain,20 28 depression28 or anxiety.21 28

Survival (n=5)

Four of five studies evaluating survival found no difference in survival between participants receiving or not receiving CAH.20 24 26 28 30 The timing of death was slightly delayed in the CAH arm of a feasibility trial (4.3 vs 2.9 days, p=0.038).20

Patient and carer attitudes (n=5)

Three studies evaluated patient and family caregiver attitudes30–32 and two focused on bereaved relatives’ views.33 34 The ‘meaning of oral intake’ was recognised as important, and of a significance beyond nutritional value.33 Although most bereaved relatives regarded reduced intake towards the end of life to be normal, concerns about both the giving and the withholding of assisted hydration were expressed, often simultaneously.33 Torres-Vigil et al found that 76% of bereaved family caregivers considered that CAH had been beneficial, and that this perception was associated with a better ‘initial adjustment to death’.34

Discussion

Fifteen studies have evaluated the impact of, or attitudes towards, CAH on the last days of life. This review has found little evidence that CAH has an impact on symptoms or survival. Patients and informal carers demonstrated varied perspectives that reflect the many uncertainties inherent to the provision of CAH at the end of life.

Although a small number of studies did report changes to symptoms or survival, the heterogeneity and low WoE of research focusing specifically on the last days of life have precluded definitive conclusions. Davies et al made a noteworthy attempt to overcome the challenges of undertaking research in this patient group, undertaking a naturalistic cluster randomised trial involving patients in the last days of life.20 The main study findings, of a slight delay in delirium onset and timing of death, are intriguing. However, this was a feasibility study, not designed to generate definitive clinical outcomes.

A number of otherwise highly relevant studies were excluded from this review because most participants were not in the last week of life, or because insufficient information had been provided to judge whether or not this was the case. In a rigorous trial, Bruera et al specifically excluded those in the last 7 days of life when randomising home hospice patients with advanced cancer to either 1000 or 100 mL of 0.9% saline daily; over 7 days there was no impact on symptoms or survival.35 Matsuo et al’s naturalistic cohort study focused on CAH in patients with advanced cancer who had been prescribed steroids, revealing an association between lower received volume of CAH and the development of delirium (p=0.034).36 Yamaguchi et al found worse agitation (p=0.025) and a higher prevalence of agitated delirium (p=0.009) in patients with advanced abdominal malignancies receiving less CAH.37 Although participants in the latter two studies were mostly in the last weeks, rather than last days, of life, (and thus excluded from this review), together with the findings from the feasibility study included in this review,20 there is a suggestion that CAH may reduce the incidence or severity of delirium as oral intake declines.

Due to the challenges of undertaking research in dying patients, few studies have focused on the perspectives of patients and their family carers in the last week of life. The qualitative study of the views of bereaved relatives included in this review, demonstrated varied perspectives on CAH at the end of life, with individuals sometimes holding complex and conflicting views.33 In contrast, a qualitative study of patients with advanced cancer in the last weeks, rather than last days, of life, found unambiguously positive views of CAH.38 This disparity may reflect the differences between views expressed in theory, and those resulting from lived experience.5 Neither study provided information on whether participants had been involved in conversations with health professionals about potential risks and benefits of hydration; Morita et al found that patients and relatives tend to adopt the perspectives of their clinicians, whether these are for, or against, the provision of CAH.39

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to review literature evaluating the provision of CAH to patients with any diagnosis in the last week of life, a time when issues of hydration are particularly relevant and challenging. Its comprehensive approach, including a wide range of study designs, participant populations and outcome measures, supports accurate identification of gaps in the literature.

The generally low WoE of the included studies, reflecting the ethical and methodological difficulties of involving dying patients in research, limited the ability to reach firm conclusions that could influence clinical practice. Due to the proximity to unconsciousness and death, studies tended to incorporate clinician-based ratings rather than self-reported measures; several involved a retrospective design to overcome the difficulty in judging prognosis. Many studies were small and underpowered. Outcome measures were heterogeneous, and some tested parameters with little salience to CAH, such as depression. Most studies only included patients with cancer, reducing the generalisability of this review. The search strategy excluded grey literature and papers not available in English language, and publication bias was not assessed.

Clinical implications

NICE guidance on ‘Care of dying adults in the last week of life’ suggests that clinicians should routinely raise and discuss the topic of hydration and CAH.11 Given the lack of evidence to guide decision-making and the concerns about both giving and withholding CAH, this review reinforces the need for highly skilled communication, including explanation of the uncertainties involved. This needs to be carefully individualised, taking into account both patient and family perspectives, as well as the potential impact of CAH decisions on the place of care. Current evidence from the UK suggests these discussions are not routinely held with documented evidence of conversations relating to CAH with 9% of dying patients and 30% of their relatives.40

In the absence of evidence, pragmatic clinical guidance is likely to be helpful. A study of HCPs’ views of guidelines for CAH in palliative care settings found that a majority (81%) would welcome guidelines that standardise care.41 Current General Medical Council guidance avoids discussion of what the benefits and burdens of CAH may be, citing a lack of clear evidence.1 This guidance focuses on the process of best interests decision making, and emphasises the importance of frequent reassessment of clinical condition. Given that there is insufficient evidence to generate definitive criteria for the use of CAH, additional guidance could usefully take a case-based approach that encourages clinicians to think through ethical and clinical arguments, while avoiding being prescriptive. In 2007, the former National Council for Palliative Care published case-based guidance on artificial nutrition and hydration at the end-of-life care,42 but this is now out of date and no longer easily accessible.

The importance of the symbolic significance and ‘meaning’ of CAH to patients and their families also has clinical implications. Guo and Jacelon argue that a major component of dignity at the end of life is ‘feeling human’.43 Some may feel that a drip detracts from feeling human by ‘medicalising’ death and keeping people in an inpatient setting; others may feel it contributes to a feeling of humanity and dignity, by symbolising ‘nurturing’ and ‘health’ in the way that drinking usually does.38 Clinicians could helpfully explore patients’ and relatives’ interpretations of the meaning they attach to CAH in order to support the process of making decisions about its provision.

Research implications

Definitive studies are urgently needed to determine whether CAH has any impact on patients’ survival or symptoms. A number of findings from this review can helpfully influence the design of future research. This review included a feasibility study with an innovative methodological approach, involving advance consent and cluster randomisation,20 that could be valuable in future trials involving dying patients. The high recruitment rate was particularly notable given the difficulties in recruiting and retaining vulnerable participants close to death. In addition, it is vital that future studies incorporate outcome measures of relevance to patients. Despite relatives’ concerns about thirst as drinking diminishes towards the end of life,5 32 44 no studies published in the last 20 years evaluated the impact of CAH on thirst.

Given the complexity of communication about an emotive topic, yet to be supported by definitive evidence, research is needed that evaluates strategies to support effective communication about CAH at the end of life. Although a recent literature review included five papers that touch on the potential for communication strategies to support families concerned about CAH-related issues,45 there has been little research focused on CAH-related communication. Finally, future research needs to involve patients with other diagnoses, including dementia and organ failure, given the preponderance of studies in cancer populations to date.

Conclusions

This review has found a limited amount of predominantly low-quality research evaluating the impact of CAH in the last days of life. There is a pressing need for well-designed studies that focus on patients specifically in the last days of life and incorporate outcome measures that take patients’ concerns into account. In the meantime, clinicians will continue to have to answer dying patients’ elemental questions about water and thirst, with little evidence on which to base the content or manner of their advice.

Footnotes

Twitter: @adnkingdon, @ilk21

Contributors: AK conducted the review and wrote the manuscript. SB and AS provided supervisory input. IK, GC and RB performed specific roles in designing a search strategy, title and abstract screening, and data extraction/quality assessment, respectively. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: AK is funded by a Health Education East of England (EoE) Academic Clinical Fellowship. SB is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration EoE programme.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. General Medical Council . Treatment and care towards the end of life: good practice in decision making, 2010. Available: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/treatment-and-care-towards-the-end-of-life/clinically-assisted-nutrition-and-hydration [Accessed 21 Jul 2020].

- 2. Hui D, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, et al. Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist 2014;19:681–7. 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morita T, Ichiki T, Tsunoda J, et al. A prospective study on the dying process in terminally ill cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1998;15:217–22. 10.1177/104990919801500407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neuberger J, Guthrie C, Aaronovich D. More care less pathway: a review of the Liverpool care pathway, 2013. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212450/Liverpool_Care_Pathway.pdf [Accessed 21 Jul 2020].

- 5. Yamagishi A, Morita T, Miyashita M, et al. The care strategy for families of terminally ill cancer patients who become unable to take nourishment orally: recommendations from a nationwide survey of bereaved family members' experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:671–83. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morita T, Shima Y, et al. Nurse views of the adequacy of decision making and nurse distress regarding artificial hydration for terminally ill cancer patients: a nationwide survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2007;24:463–9. 10.1177/1049909107302301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raijmakers NJH, Fradsham S, van Zuylen L, et al. Variation in attitudes towards artificial hydration at the end of life: a systematic literature review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2011;5:265–72. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283492ae0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raijmakers NJH, van Zuylen L, Costantini M, et al. Artificial nutrition and hydration in the last week of life in cancer patients. A systematic literature review of practices and effects. Ann Oncol 2011;22:1478–86. 10.1093/annonc/mdq620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lokker ME, van der Heide A, Oldenmenger WH, et al. Hydration and symptoms in the last days of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001729. [Epub ahead of print: 31 Aug 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CMPM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European association for palliative care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197–209. 10.1177/0269216313493685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Care of dying adults in the last days of life, 2013. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 [Accessed 21 Jul 2020]. [PubMed]

- 12. Hoare S, Morris ZS, Kelly MP, et al. Do patients want to die at home? A systematic review of the UK literature, focused on missing preferences for place of death. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142723. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Brien L. District nursing manual of clinical procedures. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Del Río MI, Shand B, Bonati P, et al. Hydration and nutrition at the end of life: a systematic review of emotional impact, perceptions, and decision-making among patients, family, and health care staff. Psychooncology 2012;21:913–21. 10.1002/pon.2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Forbat L, Kunicki N, Chapman M, et al. How and why are subcutaneous fluids administered in an advanced illness population: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:1204–16. 10.1111/jocn.13683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Good P, Richard R, Syrmis W, et al. Medically assisted hydration for adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD006273. 10.1002/14651858.CD006273.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gough D. Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res Pap Educ 2007;22:213–28. 10.1080/02671520701296189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:59. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Popay J. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davies AN, Waghorn M, Webber K, et al. A cluster randomised feasibility trial of clinically assisted hydration in cancer patients in the last days of life. Palliat Med 2018;32:733–43. 10.1177/0269216317741572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fritzson A, Tavelin B, Axelsson B. Association between parenteral fluids and symptoms in hospital end-of-life care: an observational study of 280 patients. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:160–8. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morita T, Hyodo I, Yoshimi T, et al. Association between hydration volume and symptoms in terminally ill cancer patients with abdominal malignancies. Ann Oncol 2005;16:640–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdi121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakajima N, Hata Y, Kusumuto K. A clinical study on the influence of hydration volume on the signs of terminally ill cancer patients with abdominal malignancies. J Palliat Med 2013;16:185–9. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krishna LK, Poulose J, Goh C. Artificial hydration at the end of life in an oncology ward in Singapore. Indian J Palliat Care 2010;16:165–73. 10.4103/0973-1075.73668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Otani S, Yoshimoto M, Tokuyasu N, et al. PP088-MON the association between artificial hydration and symptoms in terminally ill cancer patients. Clin Nutr 2013;32:S155. 10.1016/S0261-5614(13)60399-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cerchietti L, Navigante A, Sauri A, et al. Hypodermoclysis for control of dehydration in terminal-stage cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs 2000;6:370–4. 10.12968/ijpn.2000.6.8.9060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morita T, Tei Y, Inoue S. Agitated terminal delirium and association with partial opioid substitution and hydration. J Palliat Med 2003;6:557–63. 10.1089/109662103768253669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Viola RA. Studying fluid status and the dying - the challenge of clinical research in palliative care, MSc thesis. Canada: University of Ottowa, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Musgrave CF, Bartal N, Opstad J. The sensation of thirst in dying patients receiving i.v. hydration. J Palliat Care 1995;11:17–21. 10.1177/082585979501100404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiu T-Y, Hu W-Y, Chuang R-B, et al. Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 2002;10:630–6. 10.1007/s00520-002-0397-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Musgrave CF, Bartal N, Opstad J. Intravenous hydration for terminal patients: what are the attitudes of Israeli terminal patients, their families, and their health professionals? J Pain Symptom Manage 1996;12:47–51. 10.1016/0885-3924(96)00048-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van der Riet P, Brooks D, Ashby M. Nutrition and hydration at the end of life: pilot study of a palliative care experience. J Law Med 2006;14:182–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raijmakers NJH, Clark JB, van Zuylen L, et al. Bereaved relatives' perspectives of the patient's oral intake towards the end of life: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013;27:665–72. 10.1177/0269216313477178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Torres-Vigil I, Cohen MZ, De La Rosa A, et al. The association between past grief reactions and bereaved caregivers' perceptions of parenteral hydration during the last weeks of life. Palliat Med 2012;26:412. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:111–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matsuo N, Morita T, Matsuda Y, et al. Predictors of delirium in corticosteroid-treated patients with advanced cancer: an exploratory, multicenter, prospective, observational study. J Palliat Med 2017;20:352–9. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yamaguchi T, Morita T, Shinjo T, et al. Effect of parenteral hydration therapy based on the Japanese national clinical guideline on quality of life, discomfort, and symptom intensity in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:1001–12. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohen MZ, Torres-Vigil I, Burbach BE, et al. The meaning of parenteral hydration to family caregivers and patients with advanced cancer receiving hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:855–65. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, et al. Perceptions and decision-making on rehydration of terminally ill cancer patients and family members. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1999;16:509–16. 10.1177/104990919901600306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. NHS Benchmarking Network . National audit of care at the end of life: first round of audit report, 2019. Available: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/nhsbn-static/NACEL/2019/NACEL%20-%20National%20Report%202018%20Final%20-%20Report.pdf [Accessed 21 Jul 2020].

- 41. Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Ramos-Pichardo JD, Velasco-Álvarez ML, et al. Availability and perceived usefulness of guidelines and protocols for subcutaneous hydration in palliative care settings. J Clin Nurs 2019;28:4012–20. 10.1111/jocn.15036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Campbell C, Partridge R. Artificial nutrition and hydration: guidance in end of life care for adults. London: National Council for Palliative Care, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guo Q, Jacelon CS. An integrative review of dignity in end-of-life care. Palliat Med 2014;28:931–40. 10.1177/0269216314528399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bükki J, Unterpaul T, Nübling G, et al. Decision making at the end of life--cancer patients' and their caregivers' views on artificial nutrition and hydration. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:844. 10.1007/s00520-014-2337-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pettifer A, Froggatt K, Hughes S. The experiences of family members witnessing the diminishing drinking of a dying relative: an adapted meta-narrative literature review. Palliat Med 2019;33:1146–57. 10.1177/0269216319859728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjspcare-2020-002600supp001.pdf (122KB, pdf)