Abstract

Objectives

The secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes remain unclear. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Design

We conduced retrospective analyses on two cohorts comprising 7699 pregnant women in Beijing, China, and compared pregnancy outcomes between the pre-COVID-2019 cohort (women who delivered from 20 May 2019 to 30 November 2019) and the COVID-2019 cohort (women who delivered from 20 January 2020 to 31 July 2020). The secondary impacts of the COVID-2019 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes were assessed by using multivariate log-binomial regression models, and we used interrupted time-series (ITS) regression analysis to further control the effects of time-trends.

Setting

One tertiary-level centre in Beijing, China

Participants

7699 pregnant women.

Results

Compared with women in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic group, pregnant women during the COVID-2019 pandemic were more likely to be of advanced age, exhibit insufficient or excessive gestational weight gain and show a family history of chronic disease (all p<0.05). After controlling for other confounding factors, the risk of premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress was increased by 11% (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.18; p<0.01) and 14% (95% CI, 1.01 to 1.29; p<0.05), respectively, during the COVID-2019 pandemic. The association still remained in the ITS analysis after additionally controlling for time-trends (all p<0.01). We uncovered no other associations between the COVID-19 pandemic and other pregnancy outcomes (p>0.05).

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, more women manifested either insufficient or excessive gestational weight gain; and the risk of premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress was also higher during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, public health, fetal medicine, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A major strength of this study was our estimation of the secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in China, the first such study of its kind.

We collected materials from the hospital-information system, which assured the accuracy of our data.

This study was of a retrospective nature and thus did not include physical exercise, diet or psychological status, which might also be related to pregnancy outcomes.

The follow-up period in this study was only until delivery, such that the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and their infants could not be explored.

Introduction

COVID-19 has developed into the largest and deadliest pandemic respiratory disease. As of 23 August 2020, a total of 23 057 288 cases and 800 906 deaths have been reported to the WHO. Perinatal research on COVID-19 is now primarily focused on pregnancy outcomes of women infected with SARS-CoV-2—including caesarean section,1 2 foetal distress,1 preterm birth3 and even maternal death.4 However, the adverse secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and neonatal outcomes remain unknown.

Several investigators have explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of pregnant women.5–8 Ahorsu et al found that the fear of COVID-19 was associated with depression, suicidal intention, adverse mental-health effects and diminished overall quality of life among pregnant women.5 Some studies showed that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with obstetric care9–12—including institutional deliveries, high-risk pregnancy,9 intrapartum foetal heart rate monitoring, breastfeeding within 1 hour of birth10 and prenatal diagnosis/screening tests; while others have shown an effect of the pandemic on causing adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.9 10 13–15 The COVID-19 pandemic was associated with higher percentages of gestational hypertension,13 14 gestational diabetes (GDM)14 and premature rupture of membranes.15 Goyal et al reported that there was an increased rate of admission to the intensive care unit for pregnant women during the pandemic, compared with prior to COVID-199 Kc et al also found that both the rate of institutional stillbirth and institutional neonatal mortality increased significantly during the lockdown period in Nepal.10

However, a majority of investigators9 10 13–15 have only compared the rate of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes between the pre-COVID-19 period and the COVID-19 pandemic period without controlling important factors related to adverse pregnancy outcomes (eg, parity, gestational weight gain (GWG) or a family history of chronic disease). Thus, it is evident that more research is needed regarding the effects of the pandemic on some specific adverse outcomes, including caesarean section, foetal distress, low birth weight and macrosomia. Unfortunately, in none of the previously aforementioned studies was there an examination of the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and adverse pregnancy outcomes in mainland China.

Therefore, we aimed in the present study to evaluate the secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, using two cohorts (a pre-COVID-19 cohort and a COVID-19 cohort) to provide evidence for the implementation of targeted strategies that promote maternal and infant health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study population

Two retrospective cohorts (pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19) were analysed in this study, using the following inclusion criteria: (1) women with singleton pregnancies, (2) pregnant women who made prenatal visits to the Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Tongzhou District in Beijing and (3) women who delivered between 2019 and 31 July 2020.

There were 8324 pregnant women who gave birth between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019; and 3532 pregnant women who gave birth between 1 January 2020 and 31 July 2020. Although we herein focused on the overall effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, none of the participants was infected with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), given that the first case in China was reported in December 2019 and the first case in Beijing was reported in January 2020. To better assess the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic locally, we excluded the 613 participants who delivered during December 2019; the 344 women who delivered between 1 January 2020 and 19 January 2020; and also, the 3202 pregnant women who delivered between 1 January 2019 and 19 May 2019. Because we decided to only make close temporal comparisons in order to avoid certain potentially confounding factors (eg, differing policies between 2019 and 2020), we chose women who delivered from 20 May 2019 to 30 November 2019 as the pre-COVID-19 cohort; and those who delivered from 20 January 2020 to 31 July 2020 as the COVID-19 cohort. We thus included 4511 pregnant women in the pre-COVID-19 cohort and 3188 pregnant women in the COVID-19 cohort. However, in order to estimate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on other pregnancy outcomes (eg, preterm birth and low birth weight), we excluded two stillbirths in the pre-COVID-19 cohort and three stillbirths in the COVID-19 cohort. We therefore ultimately included 4509 pregnant women who gave birth prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and 3185 pregnant women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic (online supplemental figure 1) and online supplemental table 1).

bmjopen-2020-047900supp001.pdf (317KB, pdf)

Data collection

Data were collected from the hospital-information system, including basic demographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, occupation and education), pregnancy status (gravidity, parity, history of miscarriage and history of induced abortion), health status (prepregnancy body mass index (BMI)), GWG, a family history of chronic disease and the number of prenatal visits. Of these characteristics, prepregnancy BMI was categorised based on the WHO cut-off points; GWG was calculated as the difference between weight at the last routine pregnancy visit and the prepregnancy weight; and the rate of GWG was calculated as the GWG/the gestational weeks at the last routine pregnancy visit. Categorisation was in accordance with Institute of Medicine criteria: GWG was classified as insufficient, appropriate or excessive;16 and a family history of chronic disease was principally with respect to whether the maternal parents or maternal grandparents manifested cardiovascular diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. The number of prenatal visits was not fewer than eight times per year as recommended by the WHO.17

Assessment of pregnancy outcomes

For this study, we obtained information on pregnancy outcomes according to the International Classification of Diseases codes of discharge diagnosis, including gestational hypertension, GDM, premature rupture of membranes, delivery mode, stillbirth, foetal distress, preterm birth, low birth weight and macrosomia. Preterm birth was defined as less than 37 weeks of gestation based on the interval between the last menstrual period and the date of delivery of the baby. Delivery mode was categorised as either caesarean section or vaginal delivery. Caesarean section included both medical and psychosocial indications, and vaginal delivery included spontaneous vaginal and assisted vaginal births. Infant birth weight was divided into low birth weight (<2500 g) and macrosomia (>4000 g).

Statistical analyses

We compared the characteristics of women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic by using the χ2 or t test. The χ2 test was also used to compare pregnancy outcomes of women before and during the pandemic. Given that ORs cannot provide accurate estimates for the relative risks (RRs) in the cohort studies, we used univariate and multivariate log-binomial regression models to estimate the crude risk ratios (cRRs) and adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on adverse pregnancy outcomes using the SAS Software Package V.9.4 (SAS Institute). We also calculated the attributable risk percentage (AR%, 95% CI). We performed sensitivity analysis by fitting different models to examine the robustness of the estimation, and three models were fitted. The first (model A) was unadjusted; the second (model B) was adjusted for baseline demographic characteristics (maternal age, ethnicity, occupation and education) and the third model (full-model C) was further adjusted for pregnancy condition (gravidity, parity, history of miscarriage and history of induced abortion) and health status (pre-pregnancy BMI, GWG, family history of chronic disease and the number of prenatal visits). We additionally added a full-model C by replacing categorical variables with continuous variables, including maternal age, gravidity, parity, history of miscarriage, history of induced abortion, pre-pregnancy BMI, the rate of GWG and the number of prenatal visits. Since interrupted time-series (ITS) regression analysis is useful for evaluating population-level health interventions with a clearly defined point in time,18 we conducted ITS to examine the impacts of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes using R V.3.4.2 (R-team).18 A two-sided value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all of the analyses.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this anonymous data set.

Results

A total of 7699 women were included in this study, with a mean age of 30.07 (±3.98, SD) and an average gestational week of 38.90 (±1.46) weeks; 93.87% were of Han ethnicity, 11.83% were unemployed and 56.97% had a bachelor’s degree or less. Characteristics of the study population are provided in table 1. Compared with women in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic group, pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to be of advanced age (15.53% vs 13.30%, respectively), show insufficient (28.58% vs 26.69%) or excessive GWG (32.21% vs 31.32%), have a family history of chronic disease (14.18% vs 10.74%) and have ≥8 prenatal visits (9.50% vs 11.55%, respectively; all p<0.05). Other characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups (all p>0.05).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 7699 pregnant women before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Items | N/mean (SD) | Pre-COVID-19 (N, %; mean, SD) |

COVID-19 (N, %; mean, SD) |

χ2/t | P value |

| Maternal age (years) | 30.07 (3.98) | 29.92 (3.91) | 30.29 (4.08) | −3.42 | 0.001 |

| Maternal age (years) | 8.262 | 0.016 | |||

| ≤24 | 487 | 297 (6.58) | 190 (5.96) | ||

| 25–35 | 6117 | 3614 (80.12) | 2503 (78.51) | ||

| ≥35 | 1095 | 600 (13.30) | 495 (15.53) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 7227 | 4236 (93.90) | 2991 (93.82) | 0.022 | 0.881 |

| Other | 472 | 275 (6.10) | 197 (6.18) | ||

| Occupation | 0.202 | 0.653 | |||

| Unemployed | 911 | 528 (11.73) | 383 (12.07) | ||

| Employed | 6762 | 3972 (88.27) | 2790 (87.93) | ||

| Education | 7.782 | 0.051 | |||

| Primary school or less | 34 | 22 (0.49) | 12 (0.38) | ||

| Junior high school | 578 | 355 (7.88) | 223 (7.02) | ||

| Senior high school | 3774 | 2251 (49.94) | 1523 (47.92) | ||

| Undergraduate or above | 3299 | 1879 (41.69) | 1420 (44.68) | ||

| Gravidity | 1.99 (1.08) | 1.99 (1.07) | 2.00 (1.08) | −0.223 | 0.823 |

| Gravidity | 1.883 | 0.39 | |||

| 1 | 3068 | 1809 (40.10) | 1259 (39.49) | ||

| 2 | 2523 | 1451 (32.17) | 1072 (33.63) | ||

| ≥3 | 2108 | 1251 (27.73) | 857 (26.88) | ||

| Parity | 0.43 (0.53) | 0.43 (0.52) | 0.44 (0.54) | −0.815 | 0.415 |

| Parity | 1.362 | 0.506 | |||

| 1 | 3195 | 1849 (40.99) | 1346 (42.22) | ||

| 2 | 119 | 68 (1.51) | 51 (1.60) | ||

| ≥3 | 4385 | 2594 (57.50) | 1791 (56.18) | ||

| History of miscarriage | 0.09 (0.32) | 0.08 (0.32) | 0.09 (0.33) | −1.18 | 0.239 |

| History of miscarriage | 579 | 328 (7.27) | 251 (7.87) | 0.974 | 0.324 |

| History of induced abortion | 0.47 (0.76) | 0.48 (0.76) | 0.46 (0.76) | 0.88 | 0.379 |

| History of induced abortion | 2601 | 1559 (34.58) | 1042 (32.69) | 2.982 | 0.084 |

| Family history of chronic disease | 929 | 481 (10.74) | 448 (14.18) | 20.536 | <0.0001 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 22.04 (3.12) | 22.09 (3.17) | 21.97 (3.17) | 1.45 | 0.147 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 2.465 | 0.482 | |||

| Underweight (18.5) | 676 | 392 (8.69) | 284 (8.91) | ||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 5717 | 3375 (74.82) | 2342 (73.46) | ||

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 1079 | 610 (13.52) | 469 (14.71) | ||

| Obese (30) | 227 | 134 (2.97) | 93 (2.92) | ||

| The rate of gestational weight gain (kg /week) | 0.42 (0.09) | 0.42 (0.09) | 0.42 (0.09) | −1.035 | 0.301 |

| Gestational weight gain | 6.412 | 0.041 | |||

| Insufficient | 2115 | 1204 (26.69) | 911 (28.58) | ||

| Appropriate | 3144 | 1894 (41.99) | 1250 (39.21) | ||

| Excessive | 2440 | 1413 (31.32) | 1027 (32.21) | ||

| Prenatal visits | 11.95 (3.25) | 11.98 (3.27) | 11.90 (3.23) | 0.892 | 0.373 |

| Prenatal visits | 8.175 | 0.004 | |||

| <8 | 824 | 521 (11.55) | 303 (9.50) | ||

| ≥8 | 6875 | 3990 (88.45) | 2885 (90.50) | ||

| Total | 7699 | 4511 (58.59) | 3188 (41.41) |

Missing data: occupation, 26 (0.34%); education, 14 (0.18%); history of induced abortion, 2 (0.03%) and family history of chronic disease, 59 (0.77%).

The prevalences of caesarean sections and premature rupture of membranes were higher during the COVID-19 pandemic period compared with women prior to the pandemic (48.16% vs 45.80%, p=0.040; and 33.59% vs 30.72%, respectively; p=0.008). However, the prevalences of other pregnancy outcomes were not significantly different during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the prepandemic period (p>0.05, table 2).

Table 2.

Pregnancy outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Prevalence of outcomes (%) | Pre-COVID-19 (%) | COVID-19 (%) | χ2 | P value |

| Adverse maternal outcomes | ||||

| Gestational diabetes* | 1262 (27.99) | 872 (27.38) | 0.347 | 0.556 |

| Gestational hypertension* | 281 (6.23) | 196 (6.15) | 0.020 | 0.889 |

| Premature rupture of membranes* | 1385 (30.72) | 1070 (33.59) | 7.119 | 0.008 |

| Caesarean section* | 2065 (45.80) | 1534 (48.16) | 4.197 | 0.040 |

| Adverse foetal outcomes | ||||

| Stillbirth | 2 (0.04) | 3 (0.09) | 0.713 | 0.411† |

| Foetal distress* | 527 (11.69) | 418 (13.12) | 3.574 | 0.059 |

| Preterm birth* | 199 (4.41) | 121 (3.80) | 1.767 | 0.184 |

| Low birth weight* | 137 (3.04) | 96 (3.01) | 0.004 | 0.951 |

| Macrosomia* | 304 (6.74) | 213 (6.69) | 0.009 | 0.925 |

*These pregnancy outcomes were all based on the data from 7694 live births.

†Fisher exact test.

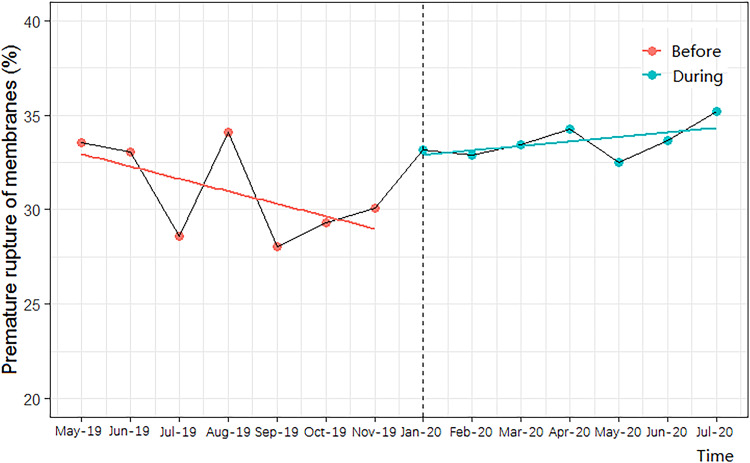

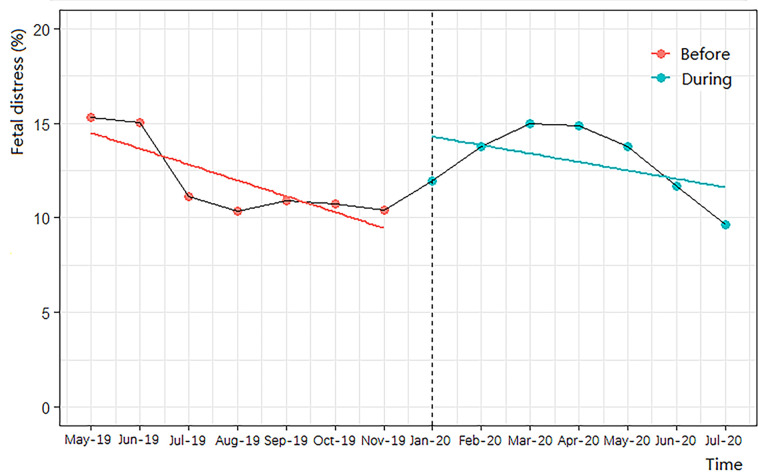

In our log-binomial regression models, and after adjusting for all confounding factors, the risk for premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-COVID-19 women was increased by 11% (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.18; p<0.01) and 14% (95% CI, 1.01 to 1.29; p<0.05), respectively (table 3). Additionally, the AR% of the COVID-19 pandemic on premature rupture of membranes was 9.91 (95% CI, 3.84, 15.25), and the AR% of the pandemic on foetal distress was 12.28 (95% CI, 0.99 to 22.48). However, we uncovered no other associations between the COVID-19 pandemic and other pregnancy outcomes, and demonstrated similar results for the additional full-model C (as shown in online supplemental table 2). After controlling for time-trends in the ITS regression, the COVID-19 pandemic was still associated with an increased risk of premature rupture of membranes (p<0.001, figure 1) and foetal distress (p<0.01, figure 2).

Table 3.

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes

| Pregnancy outcomes | Model A | Model B | Model C | |||

| cRR (95% CI) | P value | aRR (95% CI) | P value | aRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Adverse maternal outcomes | ||||||

| Gestational diabetes* | 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 0.556 | 0.97 (0.90 to 1.05) | 0.460 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.02) | 0.136 |

| Gestational hypertension* | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 0.889 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 0.920 | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.14) | 0.627 |

| Premature rupture of membranes* | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.17) | 0.007 | 1.10 (1.03 to 1.17) | 0.006 | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) | 0.003 |

| Caesarean section* | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.040 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.055 | 1.05 (1.00 to 1.10) | 0.057 |

| Adverse foetal outcomes | ||||||

| Stillbirth | 1.00 (1.00 to 100) | 0.427 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.382 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.387 |

| Foetal distress* | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.27) | 0.059 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.27) | 0.061 | 1.14 (1.01 to 1.29) | 0.028 |

| Preterm birth* | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.07) | 0.184 | 0.84 (0.68 to 1.05) | 0.135 | 0.86 (0.69 to 1.08) | 0.190 |

| Low birth weight* | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.28) | 0.951 | 0.99 (0.77 to 1.28) | 0.954 | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.30) | 0.983 |

| Macrosomia* | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.17) | 0.925 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.19) | 0.99 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.19) | 0.975 |

Model A: a univariate model without controlling for any confounding factors.

Model B: controls for demographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, occupation and education).

Model C: based on model B, supplemented to control for gravidity, parity, history of miscarriage, history of induced abortion, pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, family history of chronic disease and the number of prenatal visits.

*These pregnancy outcomes were all based on the data from 7694 live births.

aRR, adjusted risk ratio; BMI, body mass index; cRR, crude risk ratio.

Figure 1.

Interrupted time-series analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on premature rupture of membranes.

Figure 2.

Interrupted time-series analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on foetal distress.

Discussion

Summary of the findings

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first cohort study to focus on secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes in mainland China. Herein, we showed that more pregnant women were of advanced age, with abnormal GWG and a family history of chronic disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. The risks of premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress among pregnant women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic were also higher than in those women who gave birth before the pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included its cohort-study design and use of well-established methods to detect the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy outcomes, and we thus included two cohorts (a pre-COVID-19 cohort and a COVID-19 cohort), using the same study site. In addition, using log-binomial regression models and ITS analysis, we were able to evaluate the impact of a policy change or natural intervention (such as a pandemic).

There were some limitations to our study. First, this study was a retrospective study. We did not collect data on physical exercise, diet or psychological status, which might also be related to pregnancy outcomes. The follow-up period for this study was only up to delivery, such that long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and their infants could not be explored. Second, this is a single-centre cohort study, and we only included participants at one hospital in Beijing. Therefore, these results may have limited relevance to other healthcare systems outside of Beijing. Larger and multicentre prospective cohort studies are therefore needed in the future to confirm and clarify the findings of our study. Finally, due to the lack of specific individual obstetric-management records, we could not investigate the impacts of specific measures on pregnancy outcomes.

Comparison with other studies

Although researchers had previously found that the prevalence of premature rupture of membranes in pregnant women infected with the novel coronavirus was relatively high,2 19–21 few had explored the secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on this adverse pregnancy outcome. Kugelman et al found that there was a higher proportion of women who had premature rupture of membranes in a COVID-19 cohort (20.6% vs 11.0%, p<0.001)15; and in the present study, we also found that the proportion of women who presented with premature rupture of membranes was higher in the COVID-19 cohort (33.59% vs 30.72%, p=0.008). Compared with women pre-COVID-19, we observed that the risk of premature rupture of membranes during the COVID-19 pandemic was increased by 11% (95% CI, 1.04 to 1.18; p<0.01).

Premature rupture of membranes may additionally be associated with increased maternal anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.6 7 Studies have shown that as the severity of the pandemic increased, the level of anxiety among pregnant women also increased;22 and that maternal anxiety and depression were associated with premature rupture of membranes23 because of the decreased levels of creatinine and choline24 and an altered diurnal pattern of cortisol (manifested as a flattened cortisol decline and higher evening cortisol).25 26 We also found that the risk of foetal distress was increased during the pandemic, but noted a general lack of published research on this topic. The association might be related to enhanced psychological, neuroendocrine and neurochemical changes caused by social-isolation stress during the COVID-19 pandemic.27 Many countries took measures to control the transmission of the virus by keeping social distance (eg, stay-at-home orders, the cancellation of public events, lockdown), which may increase the risk of social-isolation stress for pregnant women.27 In one study, it was reported that one-third of women underwent an inadequate number of antenatal visits because of the lockdown for fear of contracting infection, resulting in 44.7% of pregnancies showing complications.9 In addition, women pregnant during the COVID-19 pandemic might not have visited the hospital as frequently as in a non-pandemic time, which might have led to under instruction in perinatal healthcare and inadequate receipt of routine medical services.28 However, the specific mechanism(s) underlying the effects on pregnancy of the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. In order to reduce the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on psychological health and increase the usage of perinatal healthcare for pregnant women during the pandemic, the National Health Commission of China launched a new notice on 8 February 2020 that proposed strengthening health counselling, screening and follow-ups for pregnant women.29 Besides, local hospital had tried their best to ensure the access to prenatal care by taking comprehensive measures (eg, online appointment service, online consultation work, outpatient service and so on) to minimise the influence of COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy and medical services. Nevertheless, our study showed that the secondary impacts of COVID-19 on pregnant women should draw greater attention, especially with respect to the premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress.

In our study, the prevalence of caesarean sections among pregnant women experiencing the COVID-19-pandemic was higher than in the group prior to the pandemic, which may be related to the higher proportions of caesarean-section indices that included foetal distress. We also found that there was a greater proportion of women aged ≥35 years in the COVID-19 cohort, and that this cohort contained more women with a family history of chronic disease. This might be related to the implementation of the two-child policy since 2016 in China that more women with advanced maternal age were willing to have babies.30 Zhao et al found that the percentages of older pregnant women increased significantly in 2017 and 2018 compared with numbers in 2014, 2015 and 2016.31 A steadily increased proportion of pregnant women with advanced age has been observed in recent years.32 Correspondingly, family members of old pregnant women were more likely to have a history of chronic diseases. What is more, the impact of second-child policy might be greater in 2020 than that in 2019 due to the policies of isolation in home and travel restrictions. Kugelman et al also found that women visited the obstetrical emergency department at a more advanced mean gestational age during the pandemic outbreak, compared with the pre-COVID period.15 Pregnant women who visit outpatient clinics should also be followed as often as possible, and the psychological and emotional states of these women should be assessed and monitored in follow-up visits to address the possible risks of adverse pregnancy complications and outcomes.33

Implications for clinicians and policymakers

Pregnant women should be considered as key populations in strategies focusing on management during COVID-19 pandemic. Service provision during the epidemic is needed to ensure the early identification and intervention of high-risk pregnant women. To ensure the access to prenatal care, hospitals should take comprehensive and case-by-case measures, assess and monitor the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in follow-up visits as often as possible.33 Additionally, apart from healthcare services, pregnant women should be educated about the importance of regular prenatal visits, healthy lifestyle and measures to prevent infection (wearing masks, hand hygiene, etc) during the COVID-19 pandemic. More attention should be paid to reduce the indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable pregnant women. Additionally, large multicentre cohort studies should be conducted in future to further explore the long-term impact and the mechanism of COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women and their babies to ensure maternal and child health.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that there were more pregnant women with abnormal GWG during the COVID-19 pandemic. The risk for premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress in pregnant women during the pandemic was also higher than in pregnant women before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings highlight the importance of improved management during pregnancy to reduce adverse maternal and infant outcomes, especially with respect to premature rupture of membranes and foetal distress. Cohort studies are needed to assess the long-term direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child health in the future.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

MD and JY contributed equally.

Contributors: All the authors have made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work. They have participated in drafting the manuscript and approval of the version to be published. Conceptualisation: JL. Methodology: JL, ML. Investigation: MD, JY and JL. Data acquisition: JY, NH. Data curation: MD, JY and JL. Data analysis: MD, JY. Preparation of tables and figures: MD. Initial draft of manuscript: MD, JY and JL. Writing—review and editing: NH, ML and JL. Supervision: JL.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81703240), the National Science and Technology Key Projects on Prevention and Treatment of Major Infectious Diseases of China (grant number 2020Z×10001002) and the National Key Research and Development Project of China (grant number 2020YFC0846300).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Peking University (IRB00001052-18003).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Gao Y-J, Ye L, Zhang J-S, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:564. 10.1186/s12879-020-05274-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Dong L, Ming L, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2) infection during late pregnancy: a report of 18 patients from Wuhan, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:394. 10.1186/s12884-020-03026-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lokken EM, Walker CL, Delaney S, et al. Clinical characteristics of 46 pregnant women with a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Washington state. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:30558–5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hantoushzadeh S, Shamshirsaz AA, Aleyasin A, et al. Maternal death due to COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223:109.e1–16. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahorsu DK, Imani V, Lin CY. Associations between fear of COVID-19, mental health, and preventive behaviours across pregnant women and husbands: an Actor-Partner interdependence modelling. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthelot N, Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, et al. Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99:848–55. 10.1111/aogs.13925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hessami K, Romanelli C, Chiurazzi M. COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemieux R, Garon-Bissonnette J, Loiselle M. Association entre la fréquence de consultation des médias d’information et la détresse psychologique chez les femmes enceintes durant la pandémie de COVID-19: Association between news media consulting frequency and psychological distress in pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can J Psychiatry 2020;706743720963917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyal M, Singh P, Singh K, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health due to delay in seeking health care: experience from a tertiary center. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021;152:231–5. 10.1002/ijgo.13457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kc A, Gurung R, Kinney MV, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: a prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1273–81. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lalaguna Mallada P, Díaz-Gómez NM, Costa Romero M, et al. [The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on breastfeeding and birth care. The importance of recovering good practices.]. Rev Esp Salud Publica 2020;94:e202007083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozalp M, Demir O, Akbas H, et al. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic process on prenatal diagnostic procedures. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020:1–6. 10.1080/14767058.2020.1815190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu X-X, Chen K, Yu H, et al. How to prevent in-hospital COVID-19 infection and reassure women about the safety of pregnancy: experience from an obstetric center in China. J Int Med Res 2020;48:300060520939337. 10.1177/0300060520939337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Justman N, Shahak G, Gutzeit O, et al. Lockdown with a price: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on prenatal care and perinatal outcomes in a tertiary care center. Isr Med Assoc J 2020;22:533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kugelman N, Lavie O, Assaf W. Changes in the obstetrical emergency department profile during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 16]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009: 240–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO . Who recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, 2016. Available: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/anc-positive-pregnancy-experience/en/ [PubMed]

- 18.Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:348–55. 10.1093/ije/dyw098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu S, Shao F, Bao B, et al. Clinical manifestation and neonatal outcomes of pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:ofaa283. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Bai J. Maternal and infant outcomes of full-term pregnancy combined with COVID-2019 in Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020;302:545–51. 10.1007/s00404-020-05573-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Wang Z, Xiong G. Clinical characteristics and laboratory results of pregnant women with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020;150:312–7. 10.1002/ijgo.13265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbett GA, Milne SJ, Hehir MP, et al. Health anxiety and behavioural changes of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;249:96–7. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khanghah AG, Khalesi ZB, Hassanzadeh R. The importance of depression during pregnancy. JBRA Assist Reprod 2020;24:405–10. 10.5935/1518-0557.20200010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Lu Y-C, Jacobs M, et al. Association of prenatal maternal psychological distress with fetal brain growth, metabolism, and cortical maturation. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1919940. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabi G, Siddique R, Xiaoyan W, et al. COVID-19 induced psychosocial stressors during gestation: possible maternal and neonatal consequences. Curr Med Res Opin 2020;36:1633–4. 10.1080/03007995.2020.1815003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilles M, Otto H, Wolf IAC, et al. Maternal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system activity and stress during pregnancy: effects on gestational age and infant's anthropometric measures at birth. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018;94:152–61. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, Nabi G, Zhang T, et al. Potential neurochemical and neuroendocrine effects of social distancing amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Endocrinol 2020;11:582288. 10.3389/fendo.2020.582288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coxon K, Turienzo CF, Kweekel L, et al. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on maternity care in Europe. Midwifery 2020;88:102779. 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Notice on strengthening maternal disease treatment and safe midwifery during the prevention and control of new coronavirus pneumonia. Available: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202002/4f80657b346e4d6ba76e2cfc3888c630 [Accessed 8 Feb 2020].

- 30.Liu J, Liu M, Zhang S, et al. Intent to have a second child among Chinese women of childbearing age following China’s new universal two-child policy: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:59–66. 10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao F, Xu Y, Chen Y-T, et al. Influence of the universal two-child policy on obstetric issues. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;252:479–82. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Song L, Qiu J, et al. Reducing maternal mortality in China in the era of the two-child policy. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002157. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vivanti AJ, Deruelle P, Picone O, et al. Follow-Up for pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: French national authority for health recommendations. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2020;49:101804. 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-047900supp001.pdf (317KB, pdf)