Abstract

Goal attainment scaling (GAS) is a method of setting and evaluating goal achievement across different patient groups. In the rehabilitation setting, this measure helps patients to identify personalised goals and evaluate their achievement over time. This report will focus on how GAS, currently embedded in clinical practice in the rehabilitation setting, may be used in pharmacy practice. The use of a coaching approach to consultations, which includes goal setting, provides an opportunity to integrate the GAS methodology into medicines-related consultations. Using examples from pharmacy practice, the report will outline methods of measuring goal attainment as part of person-centred pharmacy conversations to support medicines optimisation.

Keywords: rehabilitation, goal setting, goal attainment scaling (GAS), health coaching, behaviour change, medicines, person centred care, consultations

Introduction

Health professionals aim to provide person-centred care as integral part of every contact with patients. In 2007, the WHO published guidance on people-centred care which underpins this approach.1 This approach continues to be supported internationally through the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ ‘Choosing Wisely’ campaign.2 It aims to improve conversations between patients and healthcare professionals. In improving healthcare, methods such as motivational interviewing/coaching/behavioural interventions can increase patient responsibility and ownership and therefore motivation to make changes in their lifestyle, including improving medicines adherence.3 4 However, goal setting, despite being included in consultation skills as part of pharmacy continuing professional development,5 is not commonly used in a medicines-related consultation settings.

Kiresuk and Sherman6 initially introduced goal attainment scaling (GAS) as a means of examining outcomes in mental health trials. GAS has subsequently been embraced in rehabilitation, where it has been shown to be a successful means of empowering individuals recovering from neurological injury to optimise their health outcomes. This method offers a structured approach to goal setting which provides both the patient and the clinician with objective, measurable, outcomes over a period of time.

This paper explores the potential of using the GAS method as part of medicines-related consultations, following a presentation at the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe in 2019.7

GAS in rehabilitation

The aim of rehabilitation is to optimise a patient’s independence and functional abilities. This is done by the setting of realistic and achievable goals by the patient and/or their family/carers. The process of setting goals with a patient and/or their family is a core activity in rehabilitation.8–10 Goals can be set at different levels, from those that are global, such as goals aimed at improving quality of life, or more focal, such as goals aimed at improving speech intelligibility. Some goals are set for different outcomes, for example improving a functional outcome, such as making a cup of tea, which is different from an impairment-based goal, for example, reducing pain in a shoulder with subluxation.11

GAS is a systematic and structured approach to the evaluation of goal attainment, taking into account the fact that some goals may be achieved more readily than others, or that some may be more important to the patient.11 GAS starts with discussions between the patient/family and the multidisciplinary team regarding what goals are important to the individual. This may include negotiation of what can be realistically achieved if expectations of the patient/family are high.10 Three to five goals are usually set for the duration of the admission, documented in a SMART format (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-constrained).

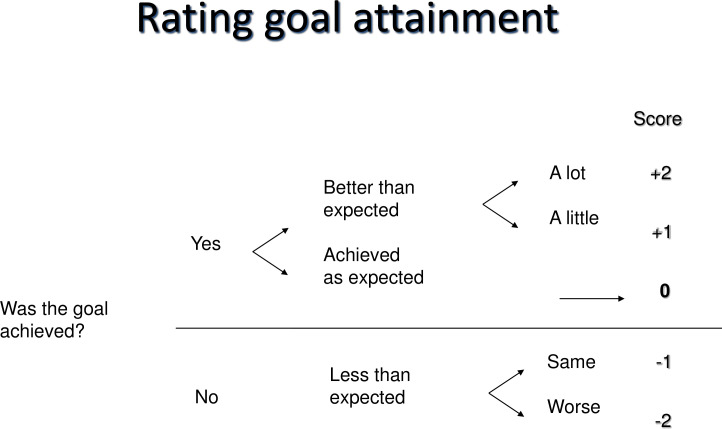

To consider attainment of the goals, a 5-point scale from −2 to +2 is the most widely used scoring system in the UK (8). Turner-Stokes10 describes the 5-point scale as follows. Prior to the period of rehabilitation, baseline function is documented at −1. If, after rehabilitation, attainment of the goal is as expected, the patient achieves a new score of 0. A score of +1 or +2 is applied if the patient achieves the goal by a little more (+1) or a lot more (+2). Equally, if the patient should deteriorate and their attainment is worse than baseline, a score of −2 is applied (see figure 1). A score of −2 would also be attributed to the baseline score if no worse condition is clinically plausible—for example, pain 10/10—or as bad as it could be. This process of goal setting and rating goal achievement as detailed above is known as the GAS ‘light’ method.11 It is interesting to note that some authors have suggested the use of a 6-point scale in order to describe the differences between partial improvement and no change more clearly.11

Figure 1.

Rating goal attainment. Reprinted with permission from Dr Stephen Ashford’s personal teaching materials.

Optional additions, to ensure the full GAS process is undertaken, are now provided. It is acknowledged that some goals matter more to a patient than to others, and some goals present more of a challenge than others. Goals can therefore be weighted to acknowledge the degree of importance to the patient/family, as well as the difficulty in attainment as rated by the treating team. Weighting is achieved by multiplying the importance score by the difficulty score.10 11

These figures may be aggregated into a single composite GAS transformation score (T-score: the sum of the attainment levels multiplied by the relative weights for each goal) reflecting the overall level of goal attainment, taking into account the respective achievement of multiple goals and their differential priority for the patient. This permits comparison of goal attainment across different populations as well as across different goal areas.10

In summary, GAS is a patient-centred goal setting measurement, flexible and responsive to patient change, providing outcomes that are of critical importance to the patient in the context of their own lives.10 Whether using the GAS ‘light’ method or the full process (with goal weighting and use of the formula), GAS provides both qualitative and quantitative information, making it a useful tool for both clinicians and researchers alike.

A coaching approach in medicines-related consultations and GAS

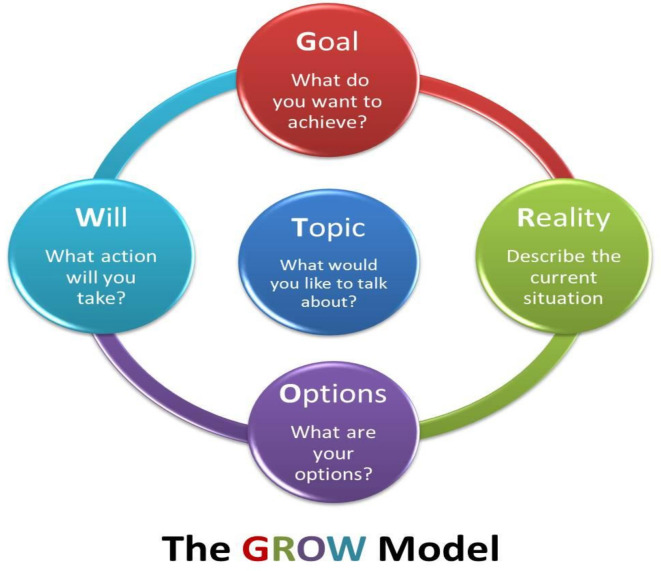

Person-centred care and shared decision making have been highlighted as important components of providing effective healthcare.1 12 13 In pharmacy, traditional consultations focused around provision of education about medicines.14 In health, there has been work to develop the use of a coaching approach to support person-centred care and shared decision making.15 The most commonly used coaching model (Goal, Reality, Options, Will/Wrap-up or GROW16) has been applied to support behaviour change in health over the last 20 years17 (see figure 2). Recent work in the East of England provided evidence that it supports positive health-related changes, and this was first explored in pharmacy in 2011.18 19 Goal setting, as part of a coaching approach to medicines-related consultations, is now included in national continuing professional development for consultations skills.5

Figure 2.

Whitmore’s16 GROW (Goal, Reality, Options, Will/Wrap-up) model.

In relation to goal setting, the ‘Goal’ in a coaching conversation is to identify what the patient wants to achieve from the conversation. GAS goals can be used as part of the ‘Will’ stage, which involves action planning the change the patient wants in relation to medicines.

An example of this is as follows:

A male patient aged 50 years, with a family history of stroke, presents with hypertension. His blood pressure reading is 150/90. His prescription record shows that he has been prescribed irbesartan 300 mg once daily for the last 6 months but has not collected his prescription for 3 months. You discuss how your patient feels about managing his hypertension, and he tells you that he would like to reduce his risk of stroke but just does not seem to be able to incorporate medicines taking into his daily routine.

Table 1 shows the elements of a conversation using the T (topic)-GROW model.

Table 1.

T-GROW conversation outline

| Topic | Your patient wants to take their medicines regularly. |

| Goal for conversation | To take medicine as prescribed. |

| Reality | They take medicines about three times a week. |

| Options | Full adherence, partial adherence, stop the medications. |

| Will/Wrap-up (action planning) | Partial adherence, better than now. |

GROW, Goal, Reality, Options, Will/Wrap-up; T, topic.

Once the patient has decided what they want do, GAS goals can be agreed with the patient, as shown in table 2.

Table 2.

GAS goal chart for antihypertensive treatment

| −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 |

| Never taking prescribed medications. | Taking medication up to three times per week. | Taking medication five times per week. | Taking medication daily. | Taking medication at the same time daily. |

The potential variability in the way GAS goals could be interpreted by different pharmacists who work with a single patient is limited because the patient has co-created the GAS goals and will support the correct interpretation.

GAS, goal attainment scaling.

GAS goals could be incorporated as part of a structured approach to consultation, as described in box 1.

Box 1. Examples of questions that could be used as part of pharmacy consultations which include goal attainment scaling goals.

I’d like to talk to you about what you want to achieve by taking this medicine, that is, your goals for medicines taking, is that OK?

What do you think is an achievable goal for you in the next time period (getting from −1 to 0)?

What would be even better (+1 and +2)?

What would be less good (−2, starting at −1)?

When shall we meet again to discuss this? (Or state next appointment time.)

Is there something else you would like to ask about this?

This type of consultation is best suited to those patients who are motivated to change their behaviour around medicines. For those who are ambivalent, indifferent or sceptical about taking medicines, this should be further explored using other methods, for example the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire,20 before considering goal setting.

If this is attempted with patients, it is important to note that patients may not be familiar with this type of consultation, so it is important to explain the process in stages. For example, explain that goal setting helps people to see how well they have achieved their aim. When asking about what a patient wants to know, it is helpful to start with an open question: ‘What goals could you set around using/taking this medicine?’ If nothing is suggested, give a number of examples as options: ‘Some people might want to achieve x, y or z. What would work for you?’

This is a novel approach to pharmacy consultations, with the first example of using GAS goals in pharmacy context published recently.21 There is an opportunity to further incorporate use of GAS goals, whether the ‘light’ or ‘full’ approach, in teaching person-centred consultations using a coaching approach, for example, as part of pharmacy consultations in hospital, which already exist,22 and for inclusion in guides for pharmacy consultations in hospital practice.23

Conclusion

This paper suggests that medicines-related consultations could include the use of the GAS method to support a structured consultation around measurable and achievable outcomes. Pharmacy staff could use the experience gained from using GAS in a rehabilitation setting and further apply this within consultations to better support medicines-related care.

What is already known on this subject.

Goal attainment scaling (GAS) was initially introduced by Kiresuk and Sherman in 1968 as a means of examining outcomes in mental health trials, and has subsequently been widely used in rehabilitation settings.

Goal setting is an accepted way of empowering patients to achieve better health outcomes.

A coaching approach to medicines-related consultations can support person-centred care.

What this study adds.

GAS can be used to support medicines-related consultations.

Skills from behavioural change techniques can facilitate use of goal setting to support medicines optimisation.

Footnotes

Twitter: @NinaLBarnett

Contributors: KC wrote the section on goal attainment scaling. NB wrote the section on use in pharmacy. KC and NB edited the paper together.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no data sets generated and/or analysed for this study.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation . People-Centred health care a policy framework. Western Pacific Region: World Health Organisation Geneva, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Academy of the Medical Royal Colleges . About choosing wisely UK, 2019. Available: https://www.choosingwisely.co.uk/about-choosing-wisely-uk/ [Accessed 1 Jul 19].

- 3. Easthall C, Song F, Bhattacharya D. A meta-analysis of cognitive-based behaviour change techniques as interventions to improve medication adherence. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002749. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD000011. 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education . Consultation skills for pharmacy practice: taking a patient-centred approach, 2014. Available: http://www.consultationskillsforpharmacy.com/docs/docb.pdf [Accessed 4 Jun 2019].

- 6. Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J 1968;4:443–53. 10.1007/BF01530764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barnett N, Clarkson K. Goal attainment scales (GAS) in person-centred pharmacy consultations. presented at 11th pharmaceutical care network Europe Conference, Egmond AAN Zee, the Netherlands, 2019. Available: https://www.pcne.org/upload/files/314_Clarkson-Barnett.pdf [Accessed 4 Jun 2019].

- 8. Playford ED, Siegert R, Levack W, et al. Areas of consensus and controversy about goal setting in rehabilitation: a conference report. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:334–44. 10.1177/0269215509103506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wade DT. Goal setting in rehabilitation: an overview of what, why and how. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:291–5. 10.1177/0269215509103551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:362–70. 10.1177/0269215508101742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ashford S, Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling in adult neuro-rehabilitation (Chapter 7). : Siegert RJ, Levack WMM, . Rehabilitation goal setting: theory, practice and evidence. Florida, USA: CRC Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Foundation, . Person-centred care made simple. London: The Health Foundation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. NHS England . The NHS long term plan, 2019. Available: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan.pdf [Accessed 4 Jun 2019].

- 14. Barnett N, Varia S, Jubraj B. Adherence: are you asking the right questions and taking the best approach? Pharm J 2013;291:153. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Health Education England . Health coaching, 2015. Available: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/health-coaching [Accessed 4 Jun 2019].

- 16. Whitmore J. Coaching for performance: growing human potential and purpose: the principles and practice of coaching and leadership. London, UK: Nicholas brierley publishing, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Ryn M, Heaney CA. Developing effective helping relationships in health education practice. Health Educ Behav 1997;24:683–702. 10.1177/109019819702400603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barnett N. The new medicine service and beyond—taking concordance to the next level. Pharm J 2011;287:653. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barnett NL, Sanghani P. A coaching approach to improving concordance. Int J Pharm Pract 2013;21:270–2. 10.1111/ijpp.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health 1999;14:1–24. 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verdoorn S, Blom J, Vogelzang T, et al. The use of goal attainment scaling during clinical medication review in older persons with polypharmacy. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019;15:1259–65. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barnett NL, Sivam R, Easthall C. Pilot study to evaluate knowledge of person-centred care, before and after a skill development programme, in a cohort of preregistration pharmacists within a large London Hospital. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2020;27:222–5. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2018-001704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barnett NL. Guide to undertaking person-centred inpatient (ward) outpatient (clinic) and dispensary-based pharmacy consultations. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2020;27:302–5. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2018-001708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]