Introduction

Burnout — a result of chronic occupational stress and defined as a combination of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of individual accomplishment1 — is rapidly becoming a serious issue for healthcare workers around the world, including nurses.2 The importance of addressing burnout is more urgent than ever;3 more than half of the 4 million registered nurses4 in the United States feeling various degrees of chronic job stress and burnout.5 Critical care nurses may be at especially high risk for burnout and burnout-related conditions.6 They care for the sickest population in intense environments, managing complex medical care and multiple technologies while providing emotional and social support to their patients and families.6 The combination of unrelenting stress, heavy workload, demanding physical and emotional environments, and a general feeling of powerlessness can create an imbalance of demand and control, leading to the development of psychological distress.7 In a study by Mealer and colleagues,8 86% of critical care nurses in their sample had symptoms consistent with burnout, 16% with anxiety, and 22% with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Thus, burnout is quite prevalent in clinicians, most especially critical care nurses.

Burnout in Nursing

While critical care nurses are prone to any of the work-stress related conditions identified in Table 1, we focus on burnout due to its prevalence and its potential for substantial consequences on clinicians, patients, organizations and society.

Table 1.

Definitions of various work-related conditions at work for nurses

| Definitions | |

|---|---|

| Burnout | Special type of work-related stress — a state of physical or emotional exhaustion that also involves a sense of reduced accomplishment and loss of personal identity.1 |

| Moral distress | First discussed by nursing; moral distress arises when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.70 |

| Moral injuries | An injury to an individual’s moral conscience resulting from an act of perceived moral transgression which produces profound emotional guilt and shame; often presented in veterans.71 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder or Secondary traumatic stress or Vicarious traumatization | Psychiatric disorder caused by exposure to a traumatic event or extreme stressor that is responded to with fear, helplessness, or horror;” experiencing, witnessing, or confrontation with an event or events that involve actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” and involves “intense fear, helplessness, or horror”6 |

| Compassion fatigue | Type of secondary traumatic stress that emanates from frontline professionals’ “cost of caring” for those who suffer psychological pain.72 Experiencing compassion fatigue can feel a loss of meaning and hope, in addition to regular burnout symptoms, a person. |

The impact of burnout on individual clinicians and patients is well-characterized. Burnout can have profound negative physical and mental health effects on individuals. For example, burnout has been linked to heart disease, chronic pain, gastrointestinal distress, depression, anxiety, PTSD, and even death.9 Even more alarming, a recent study using the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) department suggests that nurses have higher deaths from suicides than the general population.10

From the quality and safety of patient care to nurse turnover, organizations are also affected by unaddressed burnout in nurses.11–14 More specifically, emotional exhaustion— a chronic state of physical and emotional depletion from excessive job stress— has been strongly associated with worsening quality and safety of care. Indeed, higher emotional exhaustion was associated with higher standardized mortality ratios,14 urinary tract infection and surgical site infections in adult patients.11 Furthermore, nurses experiencing burnout have a reduced level of emotional attachment to their work.19 In other words, those reporting high burnout have lower job satisfaction and higher intention to leave their organization.19

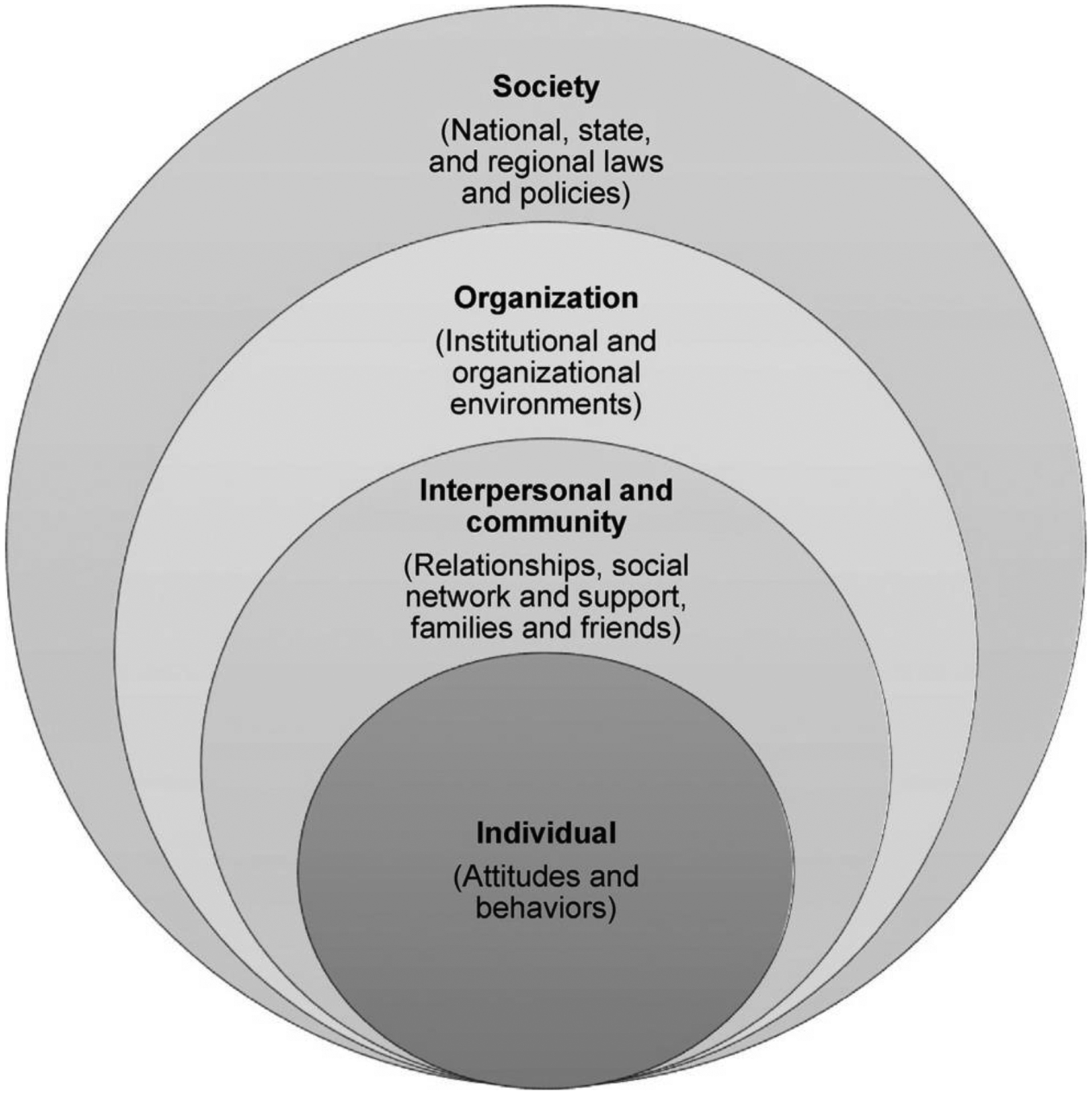

A persistent nursing shortage and rising healthcare costs are two ways in which society can be impacted by the compounding effects of burnout in nurses. In a study of newly licensed nurses, 17.9% left their jobs within the first year and 60% left within eight years.20 In the most recent report of critical care nurses, 33% of nurses intended to leave their current position within 12 months.21 Though the true costs of burnout among nurses is unclear, the related hospital costs (turnover, absenteeism, infections, etc.) are estimated to be around $9 billion annually.22 Thus, determining ways to prevent, manage and address burnout in critical care nurses is of vital importance for nurses, patients, and society (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The social-ecological model

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html)

Risk factors for burnout in nurses

While burnout can affect anyone, with or without underlying psychological diseases, there are multiple individual and organizational risk factors for nurses. At an individual level, being younger23 and a woman are known to be associated with increased risk for burnout. In a study by Kelly and colleagues,24 nurses in the “Millennial” generation (ages 21–33 years) were more likely to experience higher levels of burnout than their counterparts in the “Generation X” (ages 34–49 years) or “Baby Boomer” (ages 50–65 year). While female nurses reported more burnout than male nurses,25 how burnout manifests may vary slightly by gender. In a meta-analysis examining gender differences in burnout, women are more emotionally exhausted while men are more depersonalized (or cynical), suggesting that the overall difference of burnout between genders may not be as large as traditionally viewed.25 Further, organizational risk factors, such as high demands, low job control, heavy workloads, ethical issues, work schedule, and low wages, were associated with risk for burnout.23,26 Interestingly, key organizational characteristics such as critical care unit type (semi-closed vs open), ICU bed number, long shift lengths, or working on holidays have not been shown to risk factors for burnout in nurses that work in such environments.27

While the individual and organizational risk factors have been well studied, the role of social and interpersonal relationships at work and its impact on burnout remain under-explored. Positive interpersonal relationships and supportive teams have been reported as a source of great joy in the workplace.28,29 Thus, social relationships at work, among the nursing team, may be an important yet untapped approach to mitigate burnout, especially in critical care where teams are an essential part of the work environment.13–15 To further understand how interpersonal and social relationships could be targeted to address burnout, burnout needs to be understood as a social phenomenon through the lens of emotional contagion.

Theoretical Discussion of Emotional Contagion in Burnout

The importance of emotions in organizational behaviors has been well established since the 1930s.30A key aspect of group dynamics and how people communicate and work together is the presence of shared emotions among individuals;31 the majority of studies only explored emotions at individual levels.32 Only in recent years, researchers have started to examine how emotions transfer among group members,31 also known as emotional contagion. Emotional contagion has been defined as “the tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize facial expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another person and, consequently, to converge emotionally” [p. 5.]33 The emphasis in this definition is on non‐conscious emotional contagion. People ‘automatically’ and unconsciously mimic the facial expressions, voices, postures, and behaviors of others during conversations.34,35 Contagion may also occur via a conscious cognitive process by ‘tuning in’ to the emotions of others. This is the case when individuals empathize, attempting to imagine how they would feel in the position of another, and, therefore, experience the same feelings.31

For nursing, the profession is deeply rooted in human connections and group dynamics. However, despite the long history of exploring and creating connections with patients, nurses’ connections with each other at work are often neglected in the research of nurses’ wellbeing. The workplace is where nurses, like most working adults, spend the majority of their time. Today’s nurses face ever-increasing demands of work with rapidly changing technologies and more complex care. In addition to the demands, nurses also spend more time working in isolation compared to the previous generation, with electronic documentation and decentralized nursing stations. Unintended consequences of these technologies and rapid changes in care delivery have potentially resulted in increasing isolation among nurses. But the relationships formed at work can be a generative source of enrichment, vitality, and learning that helps individuals, groups, and organizations grow, thrive, and flourish.36 Such relationships also can be protective when they develop during stressful situations that are common in critical care settings.37–39 Thus, group dynamics and shared emotions may play a central role in ‘spreading’ burnout among its members.

Critical care nurses work in close physical proximity to one another. In critical care, there is a significant emphasis on (and need for) effective teamwork and the professional attitude is often characterized by empathic concern.40,41 These characteristics of critical care nursing are likely to foster a process of ‘tuning in’ to their nursing colleagues’ emotions and emotional state. If more nursing colleagues are burned out, this emotional state may spread among a group of nurses,42,43 leading to a phenomenon in which burnout is shared across nurses.17,22 Indeed, Bakker and his colleague22 found that burnout complaints among critical care nurse colleagues were the most important and significant predictor of burnout at the individual and unit levels. Yet, few studies have examined burnout from an emotional contagion lens. As such, few if any interventions focus on shared emotions and its role in preventing burnout. It is plausible that solutions to address burnout in critical could be most effective if they targeted the nursing team, their shared emotions and social relationships.

Current state of interventions and policies

As an increasing number of organizations recognize the negative consequences of burnout and its direct and indirect costs, interventions to address burnout have also increased.41 As shown in Table 2, these interventions are often either person-directed (individual/groups), organization-directed or a combination of both person- and organization-directed.41,44

Table 2.

Types of Interventions to address burnout among critical care nurses

| Goals | Interventions (single or multimodal) | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-directed |

|

|

| Organization-directed |

|

|

| Society-directed |

|

|

Individual-directed interventions

Individual-directed intervention programs usually include cognitive-behavioral measures aimed at enhancing job competence and personal resilience and coping skills.45 Numerous studies examined the effectiveness of individual-based interventions including mindfulness-based stress reduction, yoga, exercise classes, and/or cognitive-behavioral therapy, art sessions, and wellness activities.44,46–50 Recent meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapies on burnout demonstrated that these individual-directed coping and stress reduction strategies (e.g. cognitive therapies and mindfulness practices) were effective at reducing emotional exhaustion, but the results were less robust for depersonalization and personal accomplishment.48,49 Based on the perceived ease of introducing these interventions with promising results, hospitals and other organizations have instituted work-based wellness efforts, such as yoga and exercise programs, and weight-loss competitions.45 However, these programs are often four weeks to six months in duration, making them a challenge for nurses who are already overextended and hamstrung by scheduling conflicts (e.g., night shifts), time spent commuting, administrative burdens, and family commitments.45,50 Nonetheless, health promotion through workplace physical activity policies, incentives, and supports has the potential to prevent burnout.51

Organization-directed interventions

Organization-directed interventions are related to changes in work procedures like task restructuring, work evaluation and supervision aimed at decreasing job demand, increasing job control or the level of participation in decision making.44 These measures aim to empower individuals and reduce their experience of stressors through the creation of optimal and efficient work environments.44 For critical care nurses, the healthy work environment standards (skilled communication, true collaboration, effective decision making, appropriate staffing, meaningful recognition, and authentic leadership) endorsed by the American Association of Critical Care Nurses (AACN)52 are an example of an organization-directed intervention. Since its inception, the evidence of the relationship between the nursing work environment, patient and nurse outcomes continue to grow.21 A systematic review of nursing work environment interventions showed that interventions targeting autonomy, workload, clarity, and teamwork made significant improvement in burnout, whereas those targeting communication, management, and leadership did not.53

Society-directed interventions

Society-directed interventions are ones that focus on improving policy broadly. However, no significant legislative response to clinician burnout exists to date. In response, professional organizations have taken some steps. For example, a call to action was written and published with support from the critical care professional societies, including the AACN.54 The National Academy of Medicine launched an Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience in 2017, a network of more than 60 professional organizations committed to improving workplace culture, supporting clinician resilience, and addressing burnout.55 The Action Collaborative aims to raise awareness of burnout while advancing evidence-based, multidisciplinary solutions designed to promote the wellbeing of clinicians. Professional societies such as the AACN, the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine have also launched wellness campaigns to reduce burnout and psychological distress in critical care clinicians. Critical care conferences are increasingly adding wellness booths in the exhibit halls, where attendees can receive a massage, pet a therapy dog or talk with colleagues. While these are steps in the right direction, additional policy changes at hospitals and even a state-level are needed to address clinician burnout.

Group-based interventions using a human connection to address burnout

As demonstrated in the review of the current interventions, most are individual and organization-directed. Though a combination of individual-directed activities (e.g., meditation) and organizational policies changes have been somewhat effective, these still do not address the social nature of the problem. More powerful interventions may lie in building relationships among the nursing team due to the deeply rooted fundamentals of human connection coupled with emotional contagion of burnout. In the following section, we offer several feasible interventions to mitigate burnout in critical care nursing which focus on developing or enhancing human connection among the nursing team.

First, storytelling can be a powerful and therapeutic approach to address burnout.56 Storytelling is classically defined as the act of an individual recounting an event or a series of events verbally to one or more person(s) with plots, characters, contexts, and perspectives.57 The procedure of storytelling at work can take multiple forms, but it is with narrative skills and radical listening, storytelling could provide opportunities for meaningful connection with others through personal stories and experiences.56 Storytelling can also provide a space for nurses to voice their experiences, to be heard, to be recognized, and to be valued, thus improving and humanizing the delivery of healthcare.56,57 For example, in a study of storytelling with pediatric oncology nurses57, a bi-monthly brief informal storytelling session with two people, a storyteller and a listener, was implemented. Each person took a turn telling or listening at each session. Though the traditional format of storytelling requires both storyteller(s) and listener(s) to be in the same space as aforementioned study, the use of a digital platform or the process of creating ‘digital stories’ may be more feasible.58 Though no study of digital storytelling with nurses is published to date, patients who participated in this format of storytelling reported an increased sense of well-being and greater confidence gained through the process of creating their stories of healthcare.59 Nonetheless, the format of storytelling is less important than the act of telling and listening to a story. Furthermore, it is important to remember that storytelling is not artificially nurtured through overly contrived, and mandatory bonding activities rather remains an open and safe space for authentic relationships between colleagues to develop.

While we acknowledge that storytelling may not be not feasible in certain work settings, peer-support groups offer an alternative that have been useful in alleviating work-related stress and burnout.60 Peer-support has been well established as a beneficial approach for patients undergoing cancer treatment and more recently, for patients after an ICU stay.61 No two peer-support groups are the same, but generally they consist of a regular gathering of peers to share their experiences, struggles, and challenges in a safe and close space managed by a group leader to supervise and facilitate the discussion.60 While there are some logistical challenges to peer support groups for ICU patients,62 these are unlikely to present themselves for clinicians that work at the same hospital or in the same setting.

Similarly, expressive writing or reflective writing is another potentially effective intervention to extract thoughts and feelings about a traumatic or stressful event.63,64 For example, the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing in New York included a writing curriculum with their nursing students to tell their own stories and to hear their own work and each other’s.65 Critical care journals are also increasingly more open to publishing expressive and reflective writings as evidenced by a powerful essay on burnout by a critical care nurse in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society recently.66 More work is needed to examine, pilot and research interventions to address burnout by maximizing the strength of the community through cultivating connections and work-relationships.

Policy changes to address burnout

As discussed thus far, employing a more holistic approach is necessary to address the complex layers of burnout in critical care nurses. A policy or multiple policies on identifying, classifying, and addressing burnout must be included in the overall approach. For example, burnout is now included as an occupational phenomenon in the latest International Classification of Diseases 11.67 Nine European countries (Denmark, Estonia, France, Hungary, Latvia, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, and Sweden) are even considering burnout as an occupational disease.68 The Action Framework on the Prevention and Control of Chronic Diseases, deployed by the World Health Organization (WHO), typifies this more holistic posture by emphasizing the collection of varied and robust data to identify problematic institutional factors and environmental forces, by directing attention foremost to causes, and by encouraging interventions, implementation, and ongoing evaluation.69 To be clear, this is not to suggest burnout is itself a “disease”; it is simply to adopt a time-tested and adaptable framework used by experts trained in managing and, ideally, eradicating maladies. Drawing inspiration from the WHO’s approach to controlling diseases, while recasting burnout as a preventable rather than simply remediable condition, means proceeding in a more proactive and systematic fashion than we have yet to see in the profession. It requires us to carefully estimate and discern the current need, perhaps through surveys, town-hall meetings, or digital forums, but it also calls for nurses to be central participants—stakeholders—in advocacy campaigns and the crafting of policy, protocols, targets, tactics, and metrics for evaluation.

Summary

Plainly, the status quo for burnout is unsustainable. Risks of burnout are tri-fold; it affects the individual nurse, endangers the patients that they take care of and the public that depends on safe and effective care. Addressing burnout will require more than one simple intervention. Fostering human connection to reverse or stop emotional contagion of burnout is what may create the circumstances for nurses to flourish and prevent burnout. To achieve real change, we must reframe the way we view burnout among nurses, as something that may spread among the nursing team and target interventions at the social relationships among the nursing team. Recognizing the contagious etiology of burnout in nurses and the significance of the occupational environment is the first step in addressing this rampant issue among critical care nurses.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by the National Institute for Nursing Research (P20-NR015331) and the Center for Complexity and Self-management of Chronic Disease (PI: Costa).

References

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Org Behav. 1981;2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. NAM Perspectives. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NEJM Catalyst. Leadership Survey: Immunization Against Burnout. 2018; https://catalyst.nejm.org/survey-immunization-clinician-burnout/, 2019.

- 4.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Registered Nurses: Occupational Outlook Handbook. 2019; https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm.

- 5.McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2011;30(2):202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mealer ML, Shelton A, Berg B, Rothbaum B, Moss M. Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2007;175(7):693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. 1979:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khamisa N, Peltzer K, Oldenburg B. Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review. 2013;10(6):2214–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JE, Proudfoot J, Lee K, Zisook S. Nurse suicide in the United States: Analysis of the Center for Disease Control 2014 National Violent Death Reporting System dataset. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cimiotti JP, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Wu ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. American journal of infection control. 2012;40(6):486–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alves DF, Guirardello EB. Safety climate, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction among Brazilian paediatric professional nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(3):328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halbesleben JR, Rathert C, Williams ES. Emotional exhaustion and medication administration work-arounds: the moderating role of nurse satisfaction with medication administration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(2):95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbesleben JR, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Cooper LB. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):560–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Zheng J, Liu K, et al. Hospital nursing organizational factors, nursing care left undone, and nurse burnout as predictors of patient safety: A structural equation modeling analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;86:82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nantsupawat A, Nantsupawat R, Kunaviktikul W, Turale S, Poghosyan L. Nurse Burnout, Nurse-Reported Quality of Care, and Patient Outcomes in Thai Hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Izquierdo M, Meseguer de Pedro M, Ríos-Risquez MI, Sánchez MIS. Resilience as a Moderator of Psychological Health in Situations of Chronic Stress (Burnout) in a Sample of Hospital Nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2018;50(2):228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang HY, Friesner D, Chu TL, Huang TL, Liao YN, Teng CI. The impact of burnout on self-efficacy, outcome expectations, career interest and nurse turnover. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2018;74(11):2555–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kovner CT, Brewer CS, Fairchild S, Poornima S, Kim H, Djukic M. Newly licensed RNs’ characteristics, work attitudes, and intentions to work. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(9):58–70; quiz 70–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulrich B, Barden C, Cassidy L, Varn-Davis N. Critical Care Nurse Work Environments 2018: Findings and Implications. Crit Care Nurse. 2019;39(2):67–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Taskforce for Humanity in Healthcare. Position Paper: The Business Case for Humanity in Healthcare. 2018; https://www.vocera.com/national-taskforce-humanity-healthcare, 2019.

- 23.Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2015;52(2):649–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly L, Runge J, Spencer C. Predictors of Compassion Fatigue and Compassion Satisfaction in Acute Care Nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2015;47(6):522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purvanova RK, Muros JP. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2010;77(2):168–185. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuang CH, Tseng PC, Lin CY, Lin KH, Chen YY. Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(50):e5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vahedian-Azimi A, Hajiesmaeili M, Kangasniemi M, et al. Effects of Stress on Critical Care Nurses: A National Cross-Sectional Study. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(4):311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Taris TW. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress. 2008;22(3):187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nurses on Board Coalition. A Gold Bond to Restore Joy to Nursing: A Collaborative Exchange of Ideas to Address Burnout. 2017; https://www.nursesonboardscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/NursesReport_Burnout_Final.pdf, 2019.

- 30.Brief AP, Weiss H. Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annual review of psychology. 2002;53(1):279–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barsade SG. The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and its Influence on Group Behavior. 2002;47(4):644–675. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spector PE, Fox S. An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior: Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior. Human Resource Management Review. 2002;12(2):269–292. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatfield E, Cacioppo JT, Rapson RL. Emotional Contagion. 1993;2(3):96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernieri FJ, Reznick JS, Rosenthal R. Synchrony, pseudosynchrony, and dissynchrony: Measuring the entrainment process in mother-infant interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(2):243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adelmann PK, Zajonc RB. Facial efference and the experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology. 1989;40:249–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutton JE, Ragins BR. Moving Forward: Positive Relationships at Work as a Research Frontier. In: Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and research foundation. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2007:387–400. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenkins R, Elliott P. Stressors, burnout and social support: nurses in acute mental health settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;48(6):622–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abu Al Rub RF. The relationships between job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses, University of Iowa; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soler-Gonzalez J, San-Martin M, Delgado-Bolton R, Vivanco L. Human Connections and Their Roles in the Occupational Well-being of Healthcare Professionals: A Study on Loneliness and Empathy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fairman J, Lynaugh JE. Critical care nursing: A history. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa DK, Moss M. The Cost of Caring: Emotion, Burnout, and Psychological Distress in Critical Care Clinicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(7):787–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omdahl BL, O’Donnell C. Emotional contagion, empathic concern and communicative responsiveness as variables affecting nurses’ stress and occupational commitment. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(6):1351–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakker AB, Le Blanc PM, Schaufeli WB. Burnout contagion among intensive care nurses …reprinted from the Journal of Advanced Nursing, 51(3), 276–87. Neonatal Intensive Care. 2006;19(1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;78(2):184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jarden RJ, Sandham M, Siegert RJ, Koziol-McLain J. Strengthening workplace well-being: perceptions of intensive care nurses. Nursing in Critical Care. 2019;24(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westermann C, Kozak A, Harling M, Nienhaus A. Burnout intervention studies for inpatient elderly care nursing staff: systematic literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kravits K, McAllister-Black R, Grant M, Kirk C. Self-care strategies for nurses: A psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(3):130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee H-F, Kuo C-C, Chien T-W, Wang Y-R. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Coping Strategies on Reducing Nurse Burnout. Applied Nursing Research. 2016;31:100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cocchiara RA, Peruzzo M, Mannocci A, et al. The Use of Yoga to Manage Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duhoux A, Menear M, Charron M, Lavoie-Tremblay M, Alderson M. Interventions to promote or improve the mental health of primary care nurses: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(8):597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adlakha D Burned Out: Workplace Policies and Practices Can Tackle Occupational Burnout. Workplace Health & Safety. 2019;67(10):531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.American Association of Criticial Care Nurses, Healthy work environments. 2019; https://www.aacn.org/nursing-excellence/healthy-work-environments?tab=Patient%20Care.

- 53.Schalk DM, Bijl ML, Halfens RJ, Hollands L, Cummings GG. Interventions aimed at improving the nursing work environment: a systematic review. Implementation science : IS. 2010;5:34–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler CN. An official critical care societies collaborative statement: Burnout syndrome in critical care health care professionals: A call for action. American Journal of Critical Care. 2016;25(4):368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Academy of Medicine. Network Organizations of the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience 2017; https://nam.edu/action-collaborative-on-clinician-well-being-and-resilience-network-organizations/, 2019.

- 56.Wimberly E Story telling and managing trauma: Health and spirituality at work. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(3):48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macpherson CF. Peer-supported storytelling for grieving pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2008;25(3):148–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunsolo Willox A, Harper SL, Edge VL. Storytelling in a digital age: digital storytelling as an emerging narrative method for preserving and promoting indigenous oral wisdom. Qualitative Research. 2012;13(2):127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haigh C, Hardy P. Tell me a story — a conceptual exploration of storytelling in healthcare education. Nurse Education Today. 2011;31(4):408–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peterson U, Bergström G, Samuelsson M, Åsberg M, Nygren A. Reflecting peer-support groups in the prevention of stress and burnout: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;63(5):506–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haines KJ, Beesley SJ, Hopkins RO, et al. Peer Support in Critical Care: A Systematic Review. Critical care medicine. 2018;46(9):1522–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert E, et al. Enablers and Barriers to Implementing ICU Follow-Up Clinics and Peer Support Groups Following Critical Illness: The Thrive Collaboratives. Critical care medicine. 2019;47(9):1194–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sexton JD, Pennebaker JW, Holzmueller CG, et al. Care for the caregiver: benefits of expressive writing for nurses in the United States. Progress in Palliative Care. 2009;17(6):307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mealer M, Conrad D, Evans J, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a resilience training program for intensive care unit nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2014;23(6):e97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacobson J, Jeffries P. Nursing, Trauma, and Reflective Writing. 2018; https://nam.edu/nursing-trauma-and-reflective-writing/, 2019.

- 66.Leckie JD. I Will Not Cry. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2018;15(7):785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11. 2018; https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lastovkova A, Carder M, Rasmussen HM, et al. Burnout syndrome as an occupational disease in the European Union: an exploratory study. Ind Health. 2018;56(2):160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.World Health Organization. Occupational Health: Psychosocial risk factors and hazards. 2006; https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/risks_psychosocial/en/.

- 70.Jameton A Nursing practice: The ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shay J “Moral injury.” Psychoanalytic Psychology. 2014;31(2). 182. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoder EA. Compassion fatigue in nurses. Applied nursing research. 2010;23(4), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]