Abstract

The very important psychoactive phytocannabinoid from Cannabis Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and its non-psychotropic member is cannabidiol (CBD). These compounds have a variety of pharmacological activities. THC has been approved for the treatment of nausea caused by chemotherapy, multiple sclerosis and chronic and neuropathic pain and research is underway to use it to treat stimulation of dementia, anorexia nervous and Tourette’s syndrome. CBD has therapeutic benefits in Epilepsy, neuroprotective, cancer, inflammatory and anxiety. Recognizing candidate drugs efficiently in the new SARS-CoV2 disease 2019 (Covid-19) is crucial. Cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol have immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. They can reduce the uncontrolled cytokine production of acute lung injury. Although THD and CBD can be extracted from natural sources due to the disadvantages of this method such as difficulty in purification, cultivation, etc. It has been proven that chemical-synthesis methods of these two compounds can solve these problems. This review briefly summarizes the chemical-synthetic strategies of Dronabinol and Epidiolex from THC and CBD.

Graphic abstract

Keywords: Phytocannabinoid, Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol, Cannabidiol, SARS-CoV2, Covid-19, Dronabinol, Epidiolex

Introduction

Cannabinoids are chemicals found by the purification and isolation in Cannabis Sativa [1]. More than 200 phytocannabinoids were identified including Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC, 1), cannabinol (CBN), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabidiol (CBD; 2) (Fig. 1), etc. [2–4]. Δ9-THC is the major psychoactive compound of cannabis that it’s known in 1964 by Mechoulam and Gaoni [5, 6]. Cannabidiol was isolated by Adam et al. in 1940 and its structure was determined in 1963 by Mechoulam and Shvo; then the total configuration was determined as CBD in 1967 by Mechoulam and Gaoni [7–9]. CBD is a non-psychoactive phytocannabinoid [10]. Cannabinoids have pharmaceutical uses on two receptors called Cannabinoid receptor type 1 and type 2 (CB1&CB2) [11–18]. The two receptors are widely found in the central nervous system and periphery [19]. CBD has little interest in these receptors; however, they can act as antagonists of the two receptors [20, 21]. THC is a phytocannabinoid with psychoactive effects. In 2004, the use of a Cannabis sativa L. (Marijuana) extract was confirmed as a safe and effective treatment for HIV/AIDS, arising from anorexia and chemotherapy, from nausea and vomiting, multiple sclerosis through the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) [22, 23]. The active ingredient of this approval medicine, Dronabinol (trade names Marinol and Syndros) is a purified Cannabis-derived (−)-Δ9-trans-tetrahydrocannabinol [24, 25].

Fig. 1.

Structure of Δ9-THC (1) and cannabidiol (CBD, 2)

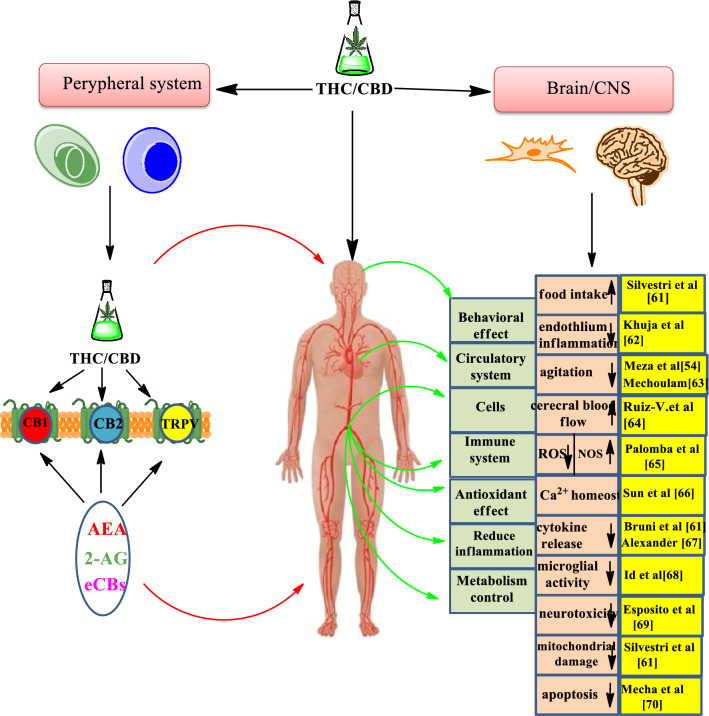

Dronabinol demonstrates very few psychoactive effects [26]. Accordingly, the World Health Organization (WHO) advised the THC for medical uses and low abuse potential in 2003 [27]. CBD is another cannabis extract that has non-psychoactive effects. In 2018, the application of (−)-trans-cannabidiol was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) (brand name Epidiolex) for the treatment of patients with epileptic seizures related to Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome [28–31]. It also has shown a potential therapeutic advantage in autism, inflammation, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [32–41]. The appearance of SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) at the end of 2019 in China has resulted in a large spread of the highly contagious and epidemic Covid-19 pandemic [42, 43]. Infection is adjusted with numerous cytokines which act to proceed with inflammatory responses [44]. In several cases of viral infections a storm of cytokines and chemokines happens through infection [45]. Recent studies have demonstrated a series of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties of cannabinoids such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol in sepsis [46–53]. The connection between the cannabinoid system and sepsis can be explained via its effects on inflammation, on the immune system and on the redox activity (Fig. 2) [54]. By acting on special receptors, CBD/THC causes the repression of cytokine manufacturing, also to a reduction in redox mechanisms [55–60].

Fig. 2.

Concepts of the endocannabinoid system in sepsis. TRPV: transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1; AEA: anandamide; 2-AG: 2-arachidonoylglycerol; eCBs: endogenous cannabinoids; ROS : reactive oxygen species; NOS: NO synthase protein

Phytocannabinoids have been obtained by extracting and purifying from the cannabis plant but their physical, chemical and structural similarities have become problematic [61]. Therefore, due to practical problems in purification and consistent quality control, the chemical synthesis route has better advantages. Considering the last two drugs made from cannabinoids and the chemical synthesis benefits of these compounds, in this review, we try to collect some of the recent publications about the chemical-synthesis strategies of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

Synthesis of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC)

Many synthetic pathways have been reported for the synthesis of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. In 1967, the primary synthetic route of Δ9-THC had published by Mechoulam et al. [62, 63]. In this method, they provided olivetylverbenyl by Friedel–Crafts alkylation in the presence of olivetol with (−)-cis/trans-verbenol in p-TSA or boron trifluoride. Olivetylverbenyl in the presence of boron trifluoride gave (−)-Δ8-THC up to 35% yield. Then, (−)-Δ8-THC was converted to (−)-Δ9-THC in 55% yield, by chlorination and elimination (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Reagents: a BF3·Et2O, CH2Cl2, rt; b ρ-TSA; c BF3·Et2O, CH2Cl2, rt and d 1. HCl, ZnCl2, toluene. 2. NaH, THF, reflux

Razdan et al. reported the direct synthesis of Δ9-THC [64]. They used p-mentha-2, 8-dien-1-ol in the presence of olivetol, Lewis acid catalyst and MgSO4. Razdan’s approach provided (−)-trans-Δ9-THC in 31% yield. This method is still used in the generation of (−)-trans-Δ9-THC because it is done in one step (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Reagents: Olivetol (5-pentylbenzene-1, 3-diol), BF3·OEt2, MgSO4

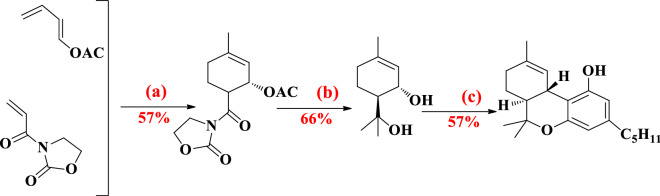

Evans et al. reported the first asymmetric synthesis of Δ9-THC [65]. They used the Diels–Alder reaction of acryloyl oxazolidinone (diene) and l-acetoxy-3-methyl butadiene in the presence of the cationic bis(oxazoline)Cu(II) catalyst and was obtained acetylated cycloadduct. This cycloadduct with LiOBn and the addition of methylmagnesium bromide produced p-menth-1-ene-3,8-diol. The diol in the presence of olivetol and p-TSA afforded (+)-trans-Δ9-THC in 57% yield (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Reagents: a, b LiOBn, MeMgBr and c p-TSA, Olivetol, ZnBr2

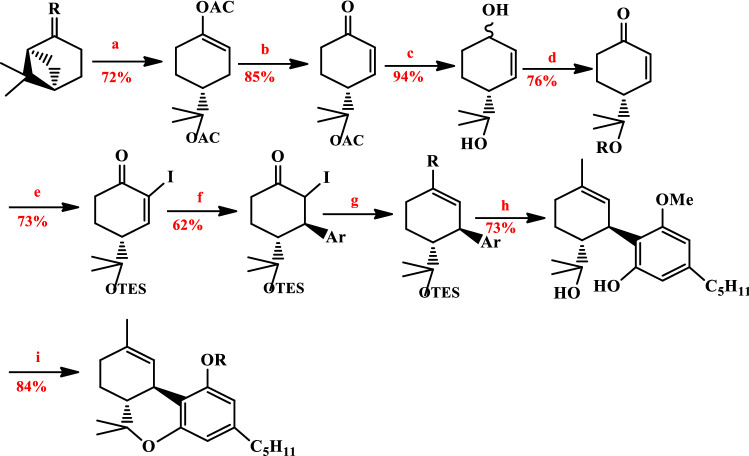

Kobayashi et al. have reported a method for synthesis of Δ9-THC inclusive the three steps: (1) iodination of the 1-cyclohex-2-enone, (2) Boron trifluoride diethyl etherate-assisted 1,4-addition of Ar2Cu (CN) Li2, (3) magnesium enolates were produced by α-iodo aryl cyclohexanone with ethylmagnesium bromide [66]. This synthetic procedure used β-pinene and ozonolysis the cyclobutane ring with zinc acetate and BF3·OEt2 in acetic anhydride formed enol acetate. The diol formed by reduction with DIBAL-H. In the following, enol phosphate was produced with α-iodoketone in the presence of EtMgBr and diethyl chlorophosphonate. The resulting intermediate was cyclized through Evans (ZnBr2, MgSO4), and finally, Δ9-THC has been produced (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Reagents: a Zn(OAc)2, BF3·OEt2, AC2O; b Pd(OAc)2, DPPE, Bu3SnOMe; c DIBAL-H; d PCC; e I2, C5H5N; f Ar2Cu(CN)Li2; g 1. EtMgBr. 2. ClP(O)(OEt)2; h NaSEt and i ZnBr2, MgSO2

Trost et al. synthesized Δ9-THC via Mo-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation reaction [67]. Allyl alcohol was prepared in four steps. Dimethyl olvitol with dry DMF formed intended aldehyde in 83% yield. Allylic alcohol was prepared through Horner–Wadsworth–Emmond reaction in the presence of sodium triethylphosphonoacetate and DIBAL-H reduction in 97% yield. In the following, allylic carbonate with sodium dimethyl malonate and [Mo (CO)3 C7H8] in the presence of chiral ligand formed branched product in 95% yield. They have prepared the intended acid from the branched product under classical conditions in 97%. Methyl esters formed by dianion of acid alkylation with iodide and provided anti- and syn-cyclohexene compounds by Grubb’s carbene catalyst. This syn compound was recycled to anti with NaOMe in MeOH. The cyclized ester formed tertiary alcohol with MeLi in 92% yield. Finally, mono-demethylation tertiary alcohol with NaSEt in the presence of ZnBr2, MgSO4, and de-protection of this product through NaSEt in dimethylformamide provided (−)-Δ9-trans-THC in 61% yield (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Reagents: a (MeO)2SO2, K2CO3, acetone; b BuLi, DMF, THF; c 1. (EtO)2P(O)CH2CO2Et, tetrahydrofuran (THF). 2. DIBAL-H, ether; d BuLi, THF, acrylaldehyde; e PdCL2(CH3CN)2, BuLi, CO2, THF; f BuLi, ClCO2CH3, ether; g ligand N,N'-((1R,2S)-cyclohexane-1,2-diyl)dipicolinamide, [MO(CO)3C7H8], sodium dimethyl malonate; h 1. NaOH. 2. HCl. 3. 160 °C; i 4-iodo-2-methylbut-1-ene, THF; j 1. (MeO)2SO2, K2CO3. 2. Grubbs catalyst; k ether, − 78 °C; l NaSEt, DMF, 140 °C and m 1. ZnBr2, MgSO4, CH2Cl2. 2. NaSEt, DMF, 140 °C

Minuti et al. used high pressure as the activating method of the Diels–Alder reactions for obtaining Δ9-cis- and Δ9-trans-THC [68]. In this method, Diels–Alder reaction was done between 3-methyl-1-(alkoxy/alkyl-substituted phenyl)buta-1,3-dienes and But-3-en-2-one(methyl vinyl ketone) under high-pressure condition (9 kbar) and then trans and cis-cyclohexenyl-benzene cycloadducts were prepared. The cis-cyclohexenyl-benzene cycloadducts produced by Diels–Alder reaction under Grignard conditions and formed pyran ring and then Δ9-cis-THC in 70% yield. Δ9-trans-THC was provided through Kobayashi and Trost methods in the presence of trans-cyclohexenyl-benzene cycloadducts by methanolic sodium methoxide, NaSMe and DMF (Fig. 8) [66, 67].

Fig. 8.

Reagents: a CH3COCH3, NaOH; b (Ph)3P=CH2, THF; c Diels–Alder reaction, 9 kbar; d MeMgBr, PhMe; e NaSMe, DMF; f TsOH, benzene; g NaSMe, DMF; h 1. MeMgBr, PhMe. 2. NaSMe, DMF and i Refs. [38, 39]

Xie et al. reported total syntheses of (–)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol by using ruthenium-catalyzed [69]. 1,4-Cyclohexene di-one-mono-ethylene acetal was iodinated at room temperature and cyclic α-iodo enone was provided in 84% yield. α-Arylated cyclic enone was prepared by the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of cyclic α-iodoenone with arylboronic acid in 93% yield. α-Arylated cyclic enone was hydrogenated on Pd/C and generated cyclic ketone in 90% yield and then under MeOCH2PPh3Cl and BuLi intended olefin was obtained in 90% yield. This olefin is produced in four steps: aqueous AcOH solution, oxidation with the Jones reagent, esterification and isomerization with NaOMe giving the intended ester in 76% yield. This ester reacted with MeMgBr and provided chiral diol in 91%yield. Finally, the produced diol promoted the SNAr reaction in basic conditions and Δ9-THC obtained in presence of ZnCl2/HCl, K-t-pentoxide in 80% yield (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Reagents: a I2, K2CO3, DMAP, THF; b Pd(PPh3)4, LiCL, Na2CO3, DME; c Pd/C, EtOH; d BuLi, MeOCH2PPh3Cl, THF; e 1. HOAc/H2O. 2. Jones reagent, acetone. 3. MeI, K2CO3, DMF. 4. NaOMe, MeOH; f CH3MgBr, THF; g NaH, Et2NCH2CH2SH, DMF and h 1. ZnCL2/HCL, AcOH. 2. K-t-pentoxide, benzene

Leahy et al. have used a chemoenzymatic synthesis of Δ9-THC and cannabidiol [70]. α,β-Unsaturated enone was prepared by methylation and formylation of olivetol. The allyl alcohol resulted from enone in two routes: (1) Corey–Bakshi–Shibata oxazaborolidine (2) reduction of α, β-unsaturated enone with sodium borohydride, acylation with vinyl butyrate acylation in presence of Savinase 12 T. Esterification of the obtained ketone and cyclization with Grubbs’ second-generation catalyst produced cyclohexene. Finally, cyclohexene with methylmagnesium iodide through Lewis acid-mediated cyclization formed (−)-trans-Δ9-THC in 57% yield (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Reagents: a 1. Me2SO4, K2CO3, 80 °C. 2. S-BuLi, DMF, − 78 °C to rt. 3. NaOH, Me2CO, 60 °C; b 1. NaBH4. 2. Savinase 12 T, vinyl butyrate. 3. NaOH, H2O, EtOH, reflax; c Oxazaborolidine, BH3THF, toluene, − 78 °C; d 1. DCC, DMAP. 2. KHMDS, − 78 °C. 3. TMSCL, py, − 78 °C to rt; e 1. Me3SiCHN2. 2. Grubbs II and f 1. MeMgI. 2. ZnBr2

Antoniotti et al. found an efficient method for Δ9-ortho-THC by two catalytic steps (Fig. 11) [71]. They used two catalysts for oxidation and cyclization of alcohols: (1) Au nanoparticle-catalysis, (2) Ti-MMT-catalysis (acid catalysis). After protonation/dehydration the allylic cation was obtained and then combined with olivetol and gave Δ9-ortho-tetrahydrocannabinol in 77% yield (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11.

Reagents: a Au NPs catalysis, O2; b Ti/MMT catalysis; c H+, − H2O; d Olivetol (5-pentylbenzene-1,3-diol) and e Hydroalkoxylation

Fig. 12.

Chemistry design for the synthesis of Δ9-ortho-THC

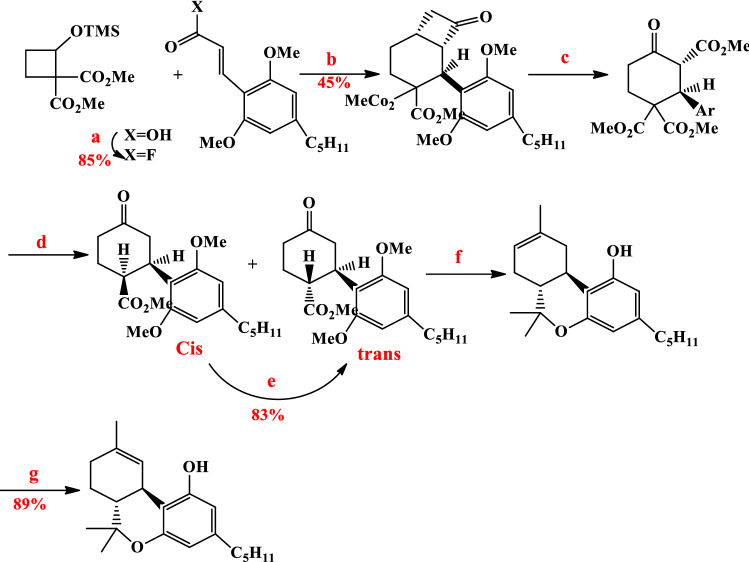

Lupton and Ametovski presented a new way to synthesize Δ9-THC by N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis [72]. Cinnamoyl fluorides and cyclobutane in the presence of NHC catalyst resulted in cycloxyl β-lactone in a 45% yield. cis- and trans-cyclohexenes were formed from lactone in the presence of KCN oxidant, IBX and Krapcho decarboxylation reaction. Trost and Dogra had reported the conversion method of the cis-to-trans mixture [67]. Finally, according to the methods performed by Carreira and Petrzilka [73, 74], the authors were obtained Δ9-THC in 89% yield (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Reagents: a DAST, CH2Cl2; b NHC, DMF/THF; c 1. KCN, MeOH. 2. IBX, EtOAc, 80 °C; d 1. LiCl, H2O, DMSO, 170 °C; e NaOMe, MeOH, 50 °C; f 1. MeMgI, Et2O, 160 °C. 2. ZnBr2, MgSO4, CH2Cl2 and g 1. ZnCl2, HCl, CH2Cl2. 2. KOC5H11, toluene

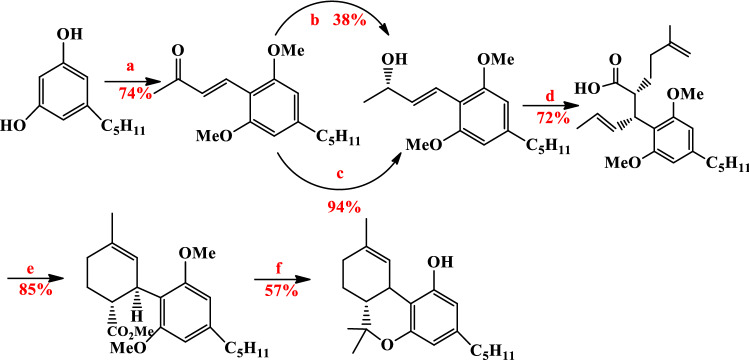

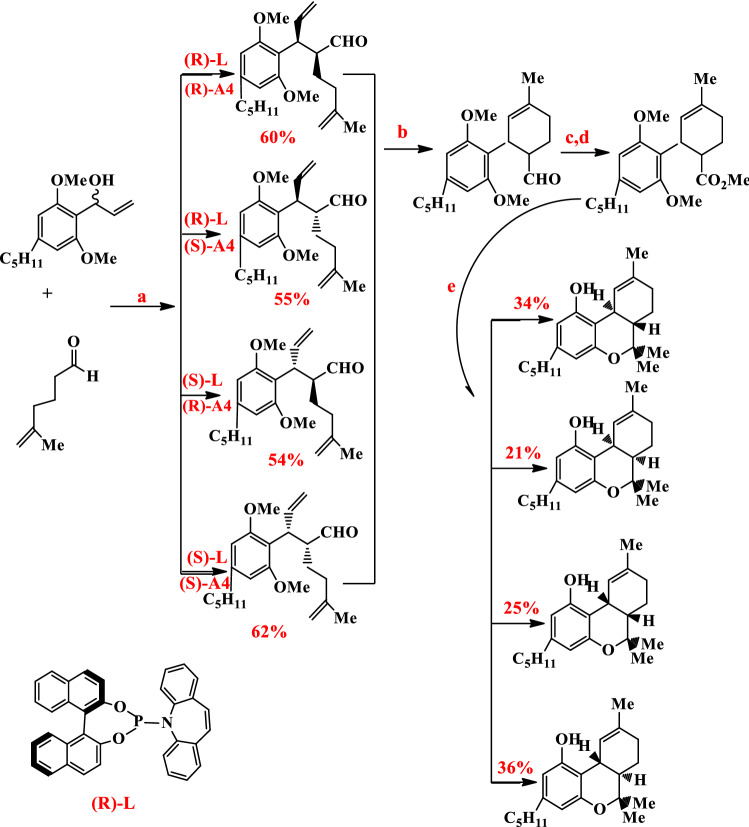

Recently synthesis of Δ9-THC was reported by Carreira et al. α-Allylation of the aldehyde with allyl alcohol by dual catalytic (Ir-(phosphoramidite, olefin)-catalyst and proline-derived Hayashi–Jorgensen catalyst (A4)) was produced all of four γ,δ-unsaturated aldehyde in 60%, 55%, 54%, and 62% yields [75]. Then cyclohexanecarbaldehydes formed from Grubbs second-generation catalyst and methyl esters were produced by Pinnick oxidation. Finally, Δ9-THC was formed by the formation of tertiary alcohol and double methyl ether deprotection and intramolecular etherification in 34%, 21%, 25%, and 36% yields (Fig. 14) [73].

Fig. 14.

Reagents: a [Ir(C8H12)Cl]2, (R)-or(s) L, (R)-or (S)A4, Zn(OTf)2, 1,2 DCE, rt, 20 h; b Grubbs II cat. 92% (S,S), 87% (R,S), 90% (S,R), 85% (R,R); c sodium chlorite, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, 2-methyl-2-butene, tBuOH/H2O, 258C; d Me3SiCHN2, C6H6/MeOH, 66% (S,S), 60% (R,S), 61% (S,R), 65% (R,R); e MeMgI, Et2O, pressure to 150 mm Hg; ZnBr2/CH2Cl2, 258C, 34%(S,S), 21% (R,S), 25% (S,R), 36%(R,R)

Keasling et al. used the biosynthesis method for the synthesis of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. They produced cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) by geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and olivetolic acid. Cannabigerolic acid was converted to tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) by the cannabinoid synthases THCAS. Δ9-THC was produced after THCA decarboxylate by heat (Fig. 15) [73].

Fig. 15.

Reagents: a CsPT4; b THCAS and c heat (ΔT)

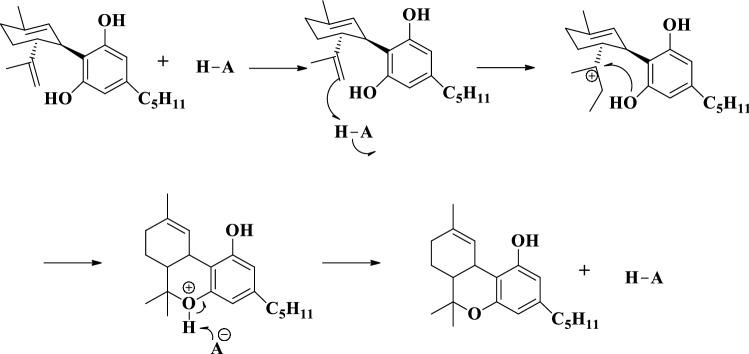

Verbeck et al. used the chemical method for produced Δ9-THC by the acid-catalyzed cannabidiol reaction with the addition of the three acids such as battery acid, muriatic acid and vinegar (Fig. 16) [76].

Fig. 16.

Isomerization reaction of cannabidiol to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

Synthesis of cannabidiol (CBD)

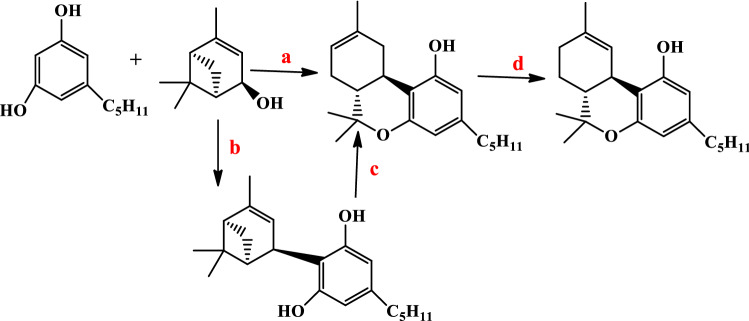

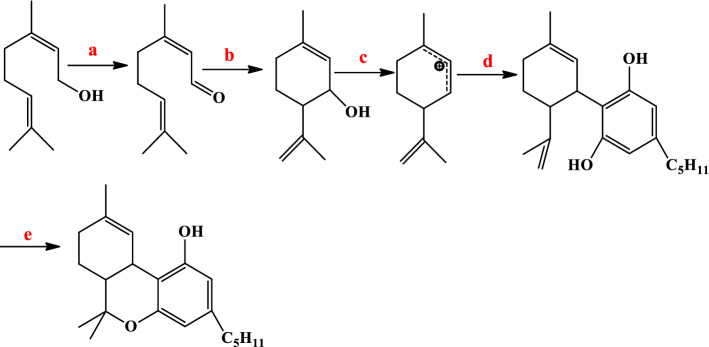

Various synthetic methods have been reported for CBD. In 1964, Mechoulam and Gaoni presented the first synthesis of cannabidiol [77]. In this study, their methods include the addition of geranial to lithiation of olivetol dimethyl ether which formed allyl alcohol. Tosylation of allyl alcohol with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride led to the cyclization, and eventually demethylation with methyl magnesium iodide. This synthesis had its drawbacks, including the production of the racemic –CBD and its low yield. In 1965, Petrzilka et al. presented a stereoselective synthesis method for (–)-CBD. The (–)-cannabidiol can be obtained through olivetol with 4-isopropenyl-1-methyl-2-cyclohexene-1-ol in the presence of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [78, 79]. In this method, the yield is a mixture of three products: (‒)-CBD: 25%, abnormal cannabidiol: 35%, (‒)-2,4-disubstituted olivetol: 5% (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

Reagents: Me2NCH (OCH2C(CH3)3)2, CH2Cl2, rt, 63 h

The remaining problem is the formation of abnormal CBD [(‒)-4-(3-3,4-trans-p-menthadien-(1,8)-yl)-olivetol] as a by-product, and this synthetic way is not practical value. Beak et al. have modified this procedure in weak acid conditions. They used boron trifluoride etherate in basic alumina (BF3·OEt2/Al2O3) as a reagent in reaction olivetol with (+)-cis/trans-p-mentha-2,8-dien-1-ol, which prevented the formation of abnormal cannabidiol. The major product was obtained at 44% yield [80].

In 1966, Korte et al. and Kochi et al. suggested a new synthetic approach. This method considers two steps: first, [4 + 2] cycloaddition of (4) and (3) as diene and dienophile which allowing the formation of cis/trans product (5). Second, a Wittig reaction gives the diastereoisomeric cis/trans (6), which produced (±)-CBD in 16% low yield after the deportation of methyl groups [81–83]. Kochi’s method differed just in the formation of (3). They procured it by a Grignard reaction and dehydration with (1) [84] (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18.

Reagents: a acetone, NaOH, 20 h, 80%; b 1. Ph3PCH3Br, BuLi, THF, 3 h. 2. 15 h, reflux, 79%; c vinyl ketone, hydroquione, toluene, 64%; d Ph3PCH3Br, BuLi, THF, 3 h, 78% and e 1. CH3I, Mg, Et2O, 130 °C. 2. 165–170 °C, 20 min, 50%

Pinnick and coworker used Diels–Alder procedures from the Claisen rearrangement reaction for prepare (±)-CBD. They have synthesized (3) by Diels–Alder reaction in the presence of (1) and methyl methacrylate (2) with DIBAL reduction. Then (5) is formed by Wittig reaction in the presence of (4) and cyclic dihydropyran intermediate. A Wittig reaction of (6) and deprotection of phenyl hydroxyl groups produce (7). Deletion of the methyl ether group of (±)-(7) produces (±)-CBD (Fig. 19) [85].

Fig. 19.

Reagents: a 1. 200 °C, C6H6, 2 h, 67%. 2. DIBAL, C6H6, − 78 °C; b Ph3PCH3Br, NaH, DMSO; c (4); d CH2Cl2, 48 h, 94% and e 1. Ph3PCH3Br, THF, n-BuLi, 3 h, r.t. 2. (6), THF, 6 h, reflux, 80%

Burdick et al. used Friedel–Craft reactions for ethyl cannabidiolate (2) and (1) in the presence of scandium triflate as a catalyst. Sc(OTf)3 has some benefits. For example, it is stable and works in the presence of aqueous solutions (Fig. 20) [86].

Fig. 20.

Reagents: a Sc(OTf)3, MgSO4, CH2Cl2, 10 °C, 3 h and b NaOH, MeOH, reflux, 5 h, 44%

Dialer et al. used protecting groups and they provided dibromide (2) in 82% yield. Then, Friedel–Crafts alkylation of dibromide intermediate (2) and (3) under acid condition produced the (4) in (90–99%) yield. Finally, reductive debromination of (4) provided (−)-CBD in 78% yield (Fig. 21) [87].

Fig. 21.

Reagents: a Br2, CH2Cl2, − 50 °C, 15 min, 82%; b ρ-TsOH·H2O, CH2Cl2, − 35 °C and c Na2SO3, ascorbic acid, Et3N, MeOH, 75 °C, 16 h, 78%

Another useful strategy for the synthesis of cannabidiol is reported with Kobayashi et al.. In this synthesis, cyclohexenylmonoacetate reacted with zinc reagent and NiCl2 (PPh3)2 as a catalyst and ligand tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) as a ligand formed (1R, 4R)-p-Mentha-2, 8-dien-1-ol (1). The compound (2) was produced by Jones oxidation and iodination from compound (1). Then compound (3) formed in the presence of boron trifluoride diethyl etherate. This enol phosphate (4) was obtained via the magnesium enolate and using a Grignard reagent through ClP(O)(OEt)2. The mixture (5) was formed under Ni-catalyzed reaction with Kumada coupling by methylmagnesium chloride. The demethylation mixture (5) led to the production of (‒)-CBD with SN2-type in good yield (Fig. 22) [88–92]. Kobayashi method is less facile than the one-step synthesis of beak.

Fig. 22.

Reagents: a NiCl2 (tpp)2, TMEDA, rt, overnight; b 1. CrO3, H2SO4. 2. I2, DBHQ, Py; c Ar2Cu (CN)Li2, BF3·OEt2, Et2O, − 78 °C, 2 h; d 1. EtMgBr. 2. ClP (O) (OEt)2, THF, 0 °C, 2 h; e MeMgCl, Ni(acac)2, THF, rt and f MeMgI, 155–165 °C

Teske et al. used a direct approach to the synthesis of CBD. In other words, olivetol was reacted with the diol (2) using the optimized Friedel–Crafts alkylation, and the triol (3) was produced in 73% yield. The mesylation of triol (3) with Et3N provided the elimination of the isopropenyl group. Then, the aromatic mesylate groups were removed with MeLi and (±)-CBD was produced in satisfactory yield (Fig. 23) [93].

Fig. 23.

Reagents: a (2), CSA, CH2Cl2, 20 °C, 3 h, 73%; b MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2; 0 °C, 1 h, then 20 °C, 16 h, 89% and c MeLi, THF, 0 °C, 1 h, 70%

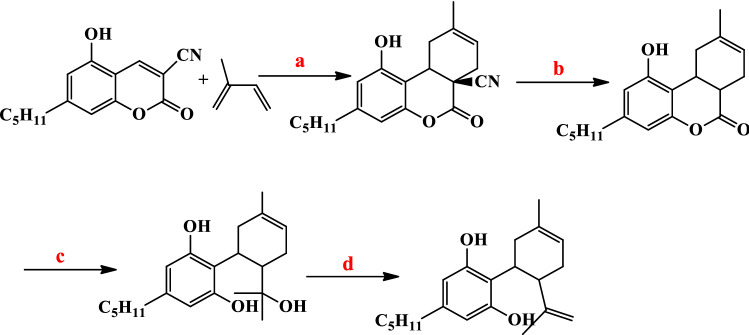

Ballerini et al. reported the synthetic route for CBD under a high-pressure Diels–Alder approach to hydroxy-substituted 6a-cyano-tetrahydro-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-ones. In this approach, 3-cyanocoumarin hydroxy dienophile reacted with isoprene ([4 + 2] cycloaddition) in mild reaction with 11 kbar pressure and produced tetrahydro-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-ones in high yields. Decyanation reaction of the cycloadducts, 6a-cyano-tetrahydro-6H-benzo[c]chromen-6-ones in aqueous solution of NaHCO3 formed cis-1-hydroxy-9-methyl-3-pentyl-6a,7,10,10atetrahydro-benzo[c]chromen-6-one. (Fig. 24) [94]. The reaction of cis-1-hydroxy-9-methyl-3-pentyl-6a,7,10,10atetrahydro-benzo[c]chromen-6-one with CH3MgI gave the triol compound and it's dehydrated with thionyl chloride in pyridine gave CBD [95].

Fig. 24.

Reagents: a Diels–Alder,11 kbar, 55 °C; b (NaHCO3)aq, PH = 8.3, 150 °C; c CH3MgI and d SOCl2, Py

Gianluca Brufola et al. prepared 3-cyano-hydroxy-substituted-coumarins by Knoevenagel condensation between salicylic aldehydes and malonitrile [96], but in this synthetic method, Ballerini et al. proposed a new environmentally friendly synthetic route for Δ9-cis-cannabidiol.

Leahy et al. have reported a synthetic method for CBD on a large scale with high enantiopurity [70]. In this synthesis, α,β-unsaturated enone was prepared from the formylation of olivetol and aldol process with acetone. They used two methods to prepare allyl alcohol: (1) CBS oxazaborolidine, (2) an enzymatic approach. In this method, (2) reduction of α,β-unsaturated enone with sodium borohydride and acylation with vinyl butyrate under enzymatic conditions (Savinase 12 T) provided allyl alcohol. Acylation of this allyl alcohol with acid after the Ireland–Claisen rearrangement provided carboxylic acid. Methylation carboxylic acid caused the formation of the corresponding ketone. CBD is produced by the Wittig olefination with Ph3P=CH2 and deprotection (Fig. 25). They have achieved CBD via inexpensive and available enzyme Savinase 12 T.

Fig. 25.

Reagents: a 1. Me2SO4, K2CO3, 80 °C. 2. S-BuLi, DMF, − 78 °C to rt. 3. NaOH, Me2CO, 60 °C; b 1. NaBH4. 2. Savinase 12 T, vinyl butyrate. 3. NaOH, H2O, EtOH, reflax; c oxazaborolidine, BH3THF, toluene, − 78 °C, d 1. DCC, DMAP. 2. KHMDS, − 78 °C. 3. TMSCL, py, − 78 °C to rt; e MeLi and f 1. Grubb’s 2nd gen. 2. Ph3P=CH2, 75 °C. 3. MeMgI, 160 °C

Stunder et al. used organometallic intermediates for the synthesis of CBD. For this method, they used alkyl derivatives of (S)-perillic acid (1). They produced the aryl iodide (3) for the arylation of olefins. For this synthesis, they used (5) in the presence of KI, m-CPBA, and crown-6 followed by methylation of dimethyl sulfide (Me2S). Finally, decarboxylation of (2) with Pd catalyze provided the (+)-CBD in 73% yield (Fig. 26) [97].

Fig. 26.

Reagents: a 1. LDA, THF, − 78 °C, 2 h. 2. DMPU, 15 min. 3. DMPU, 15 min, 90%; b (3), [Pd(dba)2], PhMe, Cs2CO3, 110 °C, 26 h, 74%; d KI, m-CPBA, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 67%, e CH3I, K2CO3, DMF, r.t. 87%

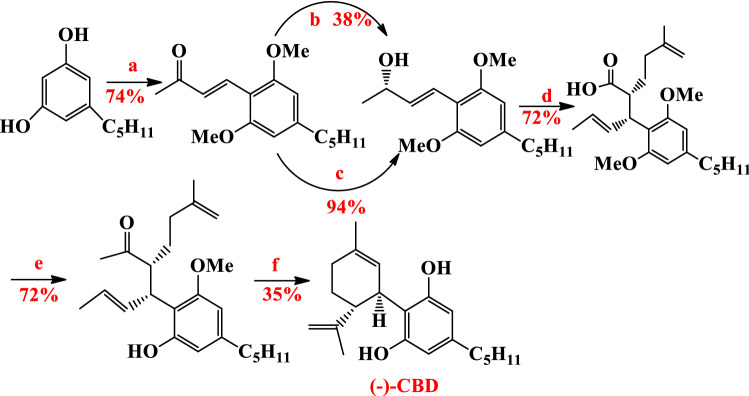

Keasling et al. used biosynthesis routes for the synthesis of cannabinoids. They used geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and olivetolic acid and produced Cannabigerolic acid (CBGA). Cannabigerolic acid was converted to cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) by the cannabinoid synthases CBDAS. CBD was produced after CBDA decarboxylate by heat (Fig. 27) [98].

Fig. 27.

Reagents: a CsPT4, b CBDAS and c heat (ΔT)

Marson et al. have proposed a new method to synthesize CBD [99]. Olivetol was condensed with the diol under optimized Friedel–Crafts conditions and the triol has been achieved in 73% yield. The mesylation of triol with Et3N eliminated the isopropenyl group and then the mesylate groups were removed by methyllithium which made (+)-cannabidiol in good yield (Fig. 28).

Fig. 28.

Reagents: a CSA, CH2Cl2; b methanesulfonyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2 and c methyllithium, THF

A new synthetic route for production of (−)-CBD and its derivatives are developed by Jingshan Shen et al. [100]. They used Friedel–Crafts alkylation of A with benzene-1,3,5-triol (phloroglucinol) and formed regioselective triflation 1 in 80% yield. They used (1) with Tf2O to prepare aryl triflate (2) in 78.1% yield. They used the Negishi cross-coupling for phenolic hydroxyl protection. Also, for obtaining CBD efficiently, they used C5H11ZnCl with lithium chloride in the presence of 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene]dichloropalladium(II) (Pd(dppf)Cl2) catalyst and the highest yield was about 20%. In this procedure, the phenolic protecting group developed the intermediate organopladium by the Negishi cross-coupling reaction. Also, they found out that the pivalate group was a great protection group; hence, (−)-CBD-2OPiv-OTf was chosen. For achieving the best 99% yield of CBD, the Piv group must be omitted, so de-protection was done (Fig. 29).

Fig. 29.

Reagents: a BF3, Et2O, THF; b Tf2O, 2,6-lutidine, DCM; c C5H11ZnCl, Pd(dppf)Cl2, LiCl, THF; d Pd(dppf)Cl2, LiCl, THF and e CH3MgBr, toluene, 110 °C, 12 h

Conclusions

Clinical researches showed effects of Δ9-THC and CBD in multiple illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, HIV/AIDS arising from anorexia and chemotherapy, from nausea and vomiting, multiple sclerosis autism, inflammation, neuropathic pain, cancer, Epilepsy and Covid-19. Cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2) interfere in many processes responsible for inflammation, redox activity, cellular metabolism and mitochondrial activity. These compounds are well applicable to provide different drugs too. These compounds are used to make four drugs of Dronabinol, Epidiolex, Nabiximols and Nabilone. In this review, we report numerous synthetic synthesis pathways for Δ9-THC and CBD. Synthetic synthesis of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol instead of extracting them from plants eliminates the problems associated with cultivation and extraction but this method still needs more preparation. Preparing new optimal methods for the synthetic synthesis of cannabinoids will cause the promotion of novel drugs.

Acknowledgements

This work supported by the “Iran National Science Foundation: INSF” and the University of Zanjan. Also, the present work has been done in line with Neda Tadayon Ph.D. Thesis.

References

- 1.Rapaka RS, Makriyannis A. National Institute on Drug Abuse. MD: Rockville; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mechoulam R, McCallum NK, Burstein S. Chem. Rev. 1976;76:75–112. doi: 10.1021/cr60299a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.L.R. Hanuš, S.M. Meyer, E. Muñoz, O. Taglialatela-Scafati, G. Appendino, Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 1357–1392 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Reekie TA, Scott MP, Kassiou M. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;2:0101. doi: 10.1038/s41570-017-0101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:1646–1647. doi: 10.1021/ja01062a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert DM, Fowler CJ. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5059–5087. doi: 10.1021/jm058183t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams R, Hunt M, Clark JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940;62:196–200. doi: 10.1021/ja01858a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mechoulam R, Shvo Y. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:2073–2078. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(63)85022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaoni Y, Mechoulam R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;12:1109–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long LE, Malone DT, Taylor DA. Drugs Future. 2005;30:747–753. doi: 10.1358/dof.2005.030.07.915908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devane WA, Dysarz FA, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Howlett AC. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;34:605–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herkenham M, Lynn AB, Little MD, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, de Costa BR. K. C. Rice. 1990;87:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.M. Herkenham, A.B. Lynn, M.R. Johnson, L.S. Melvin, B.R. de Costa, K.C. Rice J. Neurosci. 11, 563–583 (1991) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Pertwee RG. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:635–664. doi: 10.2174/0929867306666220401124036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huffman JW, Lainton JAH. Curr. Med. Chem. 1996;3:101–106. doi: 10.2174/092986730302220302094839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shar M. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mechoulam R, Peters M, Rodriguez EM, HanušL LO. Chem. Biodivers. 2007;4:1678–1692. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pertwee RG. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:199–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinol (Dronabinol) (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. September 2004. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- 22.Cannabis and Cannabinoids. National Cancer Institute. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 12 January (2014)

- 23.List of psychotropic substances under international control. International Narcotics Control Board. International Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved 25 April 2018. This international non-proprietary name refers to only one of the stereochemical variants of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, namely (−)-trans-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- 24.Chen JW, Borgelt LM, Blackmer AB. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019;53:603. doi: 10.1177/1060028018822124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung B, Lee JK, Kim J, Kang EK, Han SY, Lee HY, Choi IS. Chem. Asian J. 2018;379:795–795. doi: 10.1002/asia.201901179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calhoun SR, Galloway GP, Smith DE. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:187–196. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. World Health Organization. Retrieved 12 January (2014)

- 28.Morales P, Reggio PH, Jagerovic N. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:422–440. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA approves first drug comprised of an active ingredient derived from marijuana to treat rare, severe forms of epilepsy. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 25 (2018)

- 30.Elliott J, DeJean D, Clifford T, Coyle D, Potter BK, Skidmore B, Alexandere C, Repetski AE, McCoy VSB, Wells GA. Seizure. 2020;75:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A.R. de Mello Schier, N.P. de Oliveira Ribeiro, D.S. Coutinho, S. Machado, O. Arias-Carrion, J.A. Crippa, A.W. Zuardi, A.E. Nardi, A.C. Silva, CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 13, 953–960 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Massi P, Solinas M, Cinquina V, Parolaro D. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;75:303–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharyya S, Morrison PD, Fusar-Poli P, Martin-Santos R, Borgwardt S, Winton-Brown T, Nosarti C, Seal M, Allen P, Mehta MA, Stone JM, Tunstall N, Giampietro V, Kapur S, Murray RM, Zuardi AW, Crippa JA, Atakan Z, McGuire PK. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:764–774. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burstein S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:1377–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gegotek A, Atalay S, Domingues P, Skrzydlewska E. Cells. 2019;8:995. doi: 10.3390/cells8090995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz-Valdepenas L, Martinez-Orgado JA, Benito C, Millan A, Tolon RM, Romero J. J. Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:5–14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAllister SD, Murase R, Christian RT, Lau D, Zielinski AJ, Allison J, Almanza C, Pakdel A, Lee J, Limbad C, Liu Y, Debs RJ, Moore DH, Desprez PY. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;129:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silote GP, Sartim A, Sales A, Eskelund A, Guimaraes FS, Wegener G, Joca S. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2019;98:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ibeas Bih C, Chen T, Nunn AV, Bazelot M, Dallas M, Whalley BJ. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:699–730. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steardo L, Bronzuoli MR, Iacomino A, Esposito G, Steardo L, Scuderi C. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:259–268. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez-Ruiz J, Sagredo O, Pazos MR, Garcia C, Pertwee R, Mechoulam R, Martinez-Orgado J. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;75:323–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, et al. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55(3):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costiniuk CT, Jenabian MA. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:63–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Q. Long, X. Tang, Q. Shi et al. Nature Med. 020-0965-6 (2020)

- 46.M.D. Rizzo, J.E. Henriquez, L.K. Blevins, A. Bach, R.B. Crawford, N.E.J. Kaminski, Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 09918-7 (2020)

- 47.Rossi F, Tortora C, Argenziano M, Di Paola A, Punzo F. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2757. doi: 10.3390/ijms21082757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olah A, Szekanecz Z, Biro T. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1487. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almogi-Hazan OR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(12):E448. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tahamtan A, Tavakoli-Yaraki M, Salimi V. Expert Rev. Resp. Med. 2020;14:965–967. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1787836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mamber SW, Krawkowka S, Osborn J, et al. MSphere. 2020;5:e00288. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00288-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.A. Sattari, A. Ramazani, H. Aghahosseini, Res. Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-37994/v1 (2020)

- 53.Zarei A, Taghavi Fardood S, Moradnia F, Ramazani A. Euras. Chem. Commun. 2020;2:798–811. doi: 10.33945/SAMI/ECC.2020.7.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meza A, Lehmann C. Med. Hypotheses. 2018;110:68–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Obeid R, Herrmann W. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2994–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naviaux Rk. MITOCH. 2014;16:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horhat FG, Rogobete AF, Papurica M, Sandesc D, Tanasescu S, Dumitrascu V, Licker M, Nitu R, Cradigati CA, Sarandan M, et al. Clin. Lab. 2016;62:1601–1607. doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2016.160306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melo AC, Valença SS, Gitirana LB, Santos JC, Ribeiro LM, Machado MN, Magalhães CB, Zin WA, Porto LC. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moise A. Centr. Eur. J. Clin. Res. 2018;1:59–66. doi: 10.2478/cejcr-2018-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sandesc M, Rogobete AF, Bedreag OH, Dinu A, Papurica M, Cradigati CA, Sarandan M, Popovici SE, Bratu LM, Bratu T, et al. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018;18:191–197. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2018.2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luo X, Reiter MA, d’Espaux L, Wong J, Denby CM, Lechner A, Zhang Y, Grzybowski AT, Harth S, Lin W, Lee H, Yu C, Shin J, Deng K, Benites VT, Wang G, Baidoo EEK, Chen Y, Dev I, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD. Nature. 2019;567:123–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mechoulam R, Braun P, Gaoni Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:4552–4554. doi: 10.1021/ja00993a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mechoulam R, Braun P, Gaoni Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:6159–6165. doi: 10.1021/ja00772a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Razdan R, Puttick A, Zitko B, Handrick G. Experientia. 1972;28:121–122. doi: 10.1007/BF01935704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evans DA, Shaughnessy EA, Barnes DM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3193–3194. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00609-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.William AD, Kobayashi Y. Synthesis of tetrahydrocannabinols based on an indirect 1,4-addition strategy. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:8771–8782. doi: 10.1021/jo020457m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trost BM, Dogra K. Org. Lett. 2007;9:861–863. doi: 10.1021/ol063022k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minuti L, Ballerini E. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:5392–5403. doi: 10.1021/jo200796b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng LJ, Xie JH, Chen Y, Wang LX, Zhou QL. Org. Lett. 2013;15:764–767. doi: 10.1021/ol303351y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shultz ZP, Lawrence GA, Jacobson JM, Cruz EJ, Leahy JW. Org. Lett. 2018;20:381–384. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giorgi PD, Liautard V, Pucheault M, Antoniotti S. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018;11:1307–1311. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201800064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ametovski A, Lupton DW. Org. Lett. 2019;21:1212–1215. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schafroth MA, Zuccarello G, Krautwald S, Sarlah D, Carreira EM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:13898–13901. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1969;52:1102. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19690520427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rössler SL, Petrone DA, Carreira EM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019;52:2657–2672. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.T.D. Kiselaka, R. Koerbera, G.F. Verbecka. Forensic Sci. Int. 308 (2020)

- 77.Mechoulam R, Gaoni Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:3273–3275. doi: 10.1021/ja01092a065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petrzilka T, Sikemeier C. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1967;50:2111–2113. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19670500749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Petrzilka T, Haefliger W, Sikemeier C, Ohloff G, Eschenmoser A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1967;50:719–723. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19670500235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baek SH, Srebnik M, Mechoulam R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1083. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98518-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Korte F, Dlugosch E. U. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1966;693(1):165–170. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19666930115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Korte F, Hackel E, Sieper H. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1965;685(1):122–128. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19656850113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Claussen U, Spulak FV, Korte F. Tetrahedron. 1966;22(4):1477–1479. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99445-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kōchi H, Matsui M. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1967;31(5):625–627. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Childers WE, Pinnick HW. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49(26):5276–5277. doi: 10.1021/jo00200a061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.D.C. Burdick, S.J. Collier, F. Jos, B. Betina, H. Meckler, M.A. Helle, W. Habersha, Process for production of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (2010)

- 87.D. Lukas, P. Denis, W. Ulrich, D. Petrovic, L. Dialer, U. Weigl, D. Petrovic, U. Weig, Process for the production of cannabidiol and delta-9 Tetrahydrocannabinol (2018)

- 88.Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi A, Wang YG. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2699–2702. doi: 10.1021/ol060692h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.William AD, Kobayashi Y. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2017–2020. doi: 10.1021/ol010071i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhu D, Shi L. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:9313–9316. doi: 10.1039/C8CC03665A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Joshi-Pangu A, Wang C-Y, Biscoe MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8478–8481. doi: 10.1021/ja202769t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.William AD, Kobayashi Y. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:8771–8782. doi: 10.1021/jo020457m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Teske JA, Deiters A. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2195–2198. doi: 10.1021/ol800589e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ballerini E, Minuti L, Piermatti O, Pizzo F. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4311–4317. doi: 10.1021/jo9005365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Handrick GR, Razdan RK, Uliss DB, Dalzell HC, Boger E. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:2563–2568. doi: 10.1021/jo00435a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brufola G, Fringuelli F, Piermatti O, Pizzo F. Heterocycles. 1996;43:1257–1266. doi: 10.3987/COM-96-7447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klotter F, Studer A. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2015;54(29):8547–8550. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Luo X, Reiter MA, d’Espaux L, et al. Nature. 2019;567:123–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Waugh TM, Masters J, Aliev AE, Marson CM. Chem. Med. Chem. 2019;14:1–12. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201800799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gong X, Sun C, Abame MA, Shi W, Xie Y, Xu W, Zhu F, Zhang Y, Shen J, Aisa HA. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:2704–2715. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Silvestri C, Di Marzo V. Cell Metab. 2013;17:475–490. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Khuja I, Or Z, Yekhtin R, Almogi-Hazan O. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:668. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mechoulam R, Parker LA. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013;64:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ruiz-valdepeñas L, Martínez-orgado JA, Benito C, Millán A, Tolón RM. An intravital micros. J. Neuroinflamm. 2011;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Palomba L, Silvestri C, Imperatore R, Morello G, Piscitelli F, Martella A, Cristino L, Di V. Marzo. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:13669–13677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.646885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sun S, Hu F, Wu J, Zhang S. Redox Biol. 2017;11:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Alexander A, Smith PF, Rosengren RJ. Cancer Lett. 2009;285:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Id AJ, Gao F, Coppola G, Vogel Z, Kozela E. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0212039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Esposito G, Scuderi C, Valenza M, Togna GI, Latina V, Iuvone T, Steardo L, De Filippis D, Cipriano M, Carratu MR. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:28668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mecha M, Torrao AS, Mestre L, Carrillo-salinas FJ, Mechoulam R, Guaza C. Cell Death Discov. 2012;3:331. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Luo X, Reiter MA, d’Espaux L, et al. Nature. 2019;567:123–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]