Abstract

On 5 March 2020, South Africa recorded its first case of imported COVID-19. Since then, cases in South Africa have increased exponentially with significant community transmission. A multisectoral approach to containing and mitigating the spread of SARS-CoV-2 was instituted, led by the South African National Department of Health. A National COVID-19 Command Council was established to take government-wide decisions. An adapted World Health Organiszion (WHO) COVID-19 strategy for containing and mitigating the spread of the virus was implemented by the National Department of Health. The strategy included the creation of national and provincial incident management teams (IMTs), which comprised of a variety of work streams, namely, governance and leadership; medical supplies; port and environmental health; epidemiology and response; facility readiness and case management; emergency medical services; information systems; risk communication and community engagement; occupational health and safety and human resources. The following were the most salient lessons learnt between March and September 2020: strengthened command and control were achieved through both centralised and decentralised IMTs; swift evidenced-based decision-making from the highest political levels for instituting lockdowns to buy time to prepare the health system; the stringent lockdown enabled the health sector to increase its healthcare capacity. Despite these successes, the stringent lockdown measures resulted in economic hardship particularly for the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Keywords: COVID-19, health systems, epidemiology, public health

Summary box.

Early countrywide lockdowns enabled increased health system capacity; however, the stringent lockdowns resulted in economic hardship particularly for the most vulnerable sections of the population.

During a health emergency, it is important for leaders within a country to maintain a unified front and to continuously and accurately communicate with the public to maintain trust.

Even in a global pandemic, continuous oversight is necessary to ensure that there is accountability among leaders and to avoid corruption.

The active use of epidemiological data is a vital tool that informs the types of interventions that need to be implemented and where they should be focused.

Technology should be leveraged early in a pandemic to empower healthcare workers and communities.

Introduction

On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.1 On 11 March 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic,2 affecting almost every country globally with COVID-19 infections and deaths increasing. In preparation for an anticipated importation and local spread of COVID-19, on 30 January 2020, the South African Ministry of Health in South Africa established its incident management team, modelled on the WHO’s Framework for a Public Health Emergency Operations Centre.3 A National COVID-19 Command and Control Council (NCCC) was established by the national Cabinet on 15 March 2020 for intergovernment coordination and to take government-wide decisions.

On 5 March 2020, the first imported case of COVID-19 was reported in the KwaZulu-Natal province.4 Subsequently, clusters of cases were reported from around the country, rapidly followed by community transmission. Between March and August, South Africa reported the highest number of cases on the African continent. In this paper, the measures taken by South Africa to contain the spread of COVID-19 and to mitigate its effects are described.

Local setting

South Africa has a population of 59.2 million people living across nine provinces. South Africa is situated on the southern tip of the African Continent and is home to approximately 59.2 million persons.5 South Africa comprises nine provinces (Eastern Cape, Free-State, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape, North West and Western Cape); in terms of geographical size, Gauteng is the smallest but most densely populated and the Northern Cape is the largest and is sparsely populated.6

The country is classified as an upper middle-income country by the World Bank; however, the Inequality Index has rated South Africa as one of the most unequal countries in the world in terms of economic distribution. The South African healthcare system is two tiered, comprising of a public, government-run sector and a private sector.7 The services in the public healthcare sector are divided into primary (clinics), secondary (district and regional hospitals) and tertiary (academic) health services.7 The National Department of Health is responsible for the development of health-related policies and guidelines,7 which are then implemented at provincial and district levels.

Approach

The Minister of Health, Dr Zwelini Mkhize, announced the first case of COVID-19 in South Africa on 5 March 2020 in Parliament and subsequently to the Nation. On 15 March 2020, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a National State of Disaster.8

Having established an incidence management system and an incident management team (IMT) in January 2020, as well as the NCCC, South Africa had plans in place to contain the spread of the virus. The purpose of an incident management system and team is to establish a structured approach for managing a public health emergency, by integrating existing healthcare functions into an emergency management model.3 Five essential functions are described in an incident management system: management, operations, planning, logistics and, finance and administration.3

South Africa’s IMT was further organised into key functional areas comprising Governance and Leadership; Medical Supplies; Port Health and Environmental Health, Epidemiology and Response; Facility Readiness & Case Management; Emergency Medical Services, Information Systems, Risk Communication & Community Engagement; Occupational Health and Safety and Human Resources. The IMT comprises members specifically selected to oversee each functional area and the prevention and control strategies that were developed and implemented across South Africa. In the following section, the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa is described.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients were not involved in this study.

South African COVID-19 cases and key milestones

As of 30 September 2020, 209 days after the first case was identified, South Africa had conducted 4 187 917 tests, recorded 674 339 COVID-19 cases and 16 734 deaths.9 South Africa ranked 10th globally with the highest number of cumulative cases.9 Within Africa, South Africa had the highest number of cases followed by Morocco (123 653 cases) and Egypt (103 193 cases).10

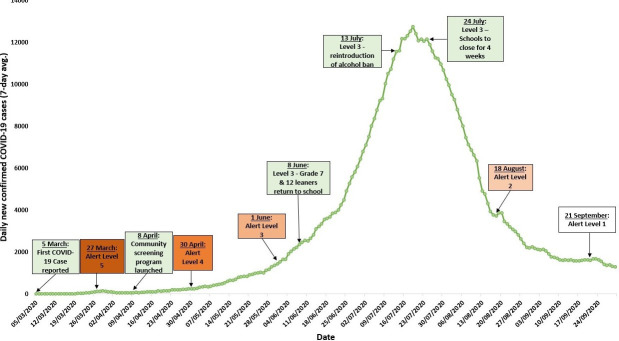

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of the South African COVID-19 pandemic since the first reported case. The graph shows the key milestones in South Africa alongside the 7-day moving average of new COVID-19 cases. Twenty-two days after the first COVID-19 was reported, South Africa went into a national lockdown. The national lockdown at risk-adjusted level 5 was in place for just over a month, after which the alert level 4 was introduced. Changes in the levels were related to the number of active cases as well as the capacity of the health system to respond in terms of availability of beds to treat patients. Alert level 3 was introduced on 1 June 2020, after which the number of COVID-19 cases started to rapidly rise, until the daily new cases peaked around 19 July 2020. The counterintuitive nature of adjusting to level 3 as COVID-19 cases were rising is attributed to the balancing act between the public health risks associated with COVID-19 and the need to restart the economy to protect the livelihoods of the most vulnerable populations.

Figure 1.

Graph showing South Africa’s key milestones alongside the rolling average of daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Despite the early interventions initiated to curb the spread of COVID-19 in South Africa, an exponential increase in COVID-19 cases was experienced, as depicted in figure 1. It is speculated that the rapid rise in infections was due to poor adherence to isolation and quarantine guidelines and to nonpharmaceutical interventions—which were exacerbated by high levels of alcohol consumption and socioeconomic factors (eg, areas with high population and household densities and lack of access to clean water in each household in some areas). Furthermore, the return of migrant workers to work, which was observed after the transition from level 5 to 4 contributed to the spread of and increases in COVID-19 cases. The key strategies introduced in figure 1 will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

Strategies

In the absence of a widely available vaccine to prevent the rapid spread of the virus, the importance of nonpharmaceutical interventions has been emphasised globally. In South Africa’s National Plan for COVID-19 Health Response (May 2020), nine strategic priorities were identified, these are to11

Provide effective governance and leadership.

Strengthen surveillance and strategic information.

Augment health systems readiness including emergency medical services.

Enhance community engagement.

Improve laboratory capacity and testing.

Clarify care pathways.

Scale-up infection prevention and control measures.

Boost capacity at ports of entry.

Expedite research and introduction of therapeutics, diagnostics and vaccines.

Of these strategies, the challenges and lessons learnt in five areas will be discussed in detail, namely, active and informed use of epidemiological data; community engagement and risk communication; South Africa’s risk-adjusted strategy; capacity building and contact tracing and community screening. It should be noted that this is not an exhaustive list of the strategies that were employed in South Africa’s fight against COVID-19, these strategies were identified as having the greatest impact in impeding the rapid spread of COVID-19.

Active and informed use of epidemiological data

Epidemiological data were used to identify which geographic areas were hotspots and where to implement prevention and control strategies. By using epidemiological data, interventions were adapted to ensure that these were culturally appropriate and effective in the identified hotspots. In addition, a robust monitoring and evaluation framework was developed to track progress and impact. Some of the best practices by the South African epidemiology team include the formation of a sentinel hospital surveillance system, which collected data used to monitor bed utilisation. In addition, COVID-19 data were rapidly integrated into the existing influenza and pneumonia surveillance system and the South African COVID-19 Modelling Consortium was established. The models developed by this consortium were used to guide planning and implementation. Challenges experienced included the lack of standardised, synchronised systems for surveillance and reporting—which was subsequently remedied by integrating COVID-19 data collection into the existing influenza and pneumonia surveillance system. Initially the various systems collecting the same data accross provinces and health programmes led to data collection being duplicated and resulted in inadequate coordination between the COVID-19 response and other healthcare programmes.

Community engagement and risk communication

A key strategy that was employed early in the pandemic was community engagement and risk communication. A Risk Communication and Community Engagement Working group was established in March 2020. Using lessons and best practices learnt within the country as well as internationally, the working group developed a community communication strategy. There was continuous communication with the population and messages were disseminated through a variety of channels including WhatsApp, radio, television and the internet in all the official South African languages. Daily, COVID-19 communication was carried out in order to build and maintain the public’s trust. Challenges within this intervention area included the spread of misinformation and rumours on social media and limited financial resources available and allocated to communication and engagement. Challenges surrounding community engagement and risk communication included difficulties in managing communication, which was disseminated outside of the department of health, particularly the spread of COVID-19 rumours and misinformation.

Risk-adjusted strategy to curtail human interaction

A five-level risk-adjusted strategy was developed by the NCCC to contain the spread of COVID-19 by imposing various economic and social measures, including limits on local and international travel, the closure of educational institutions, a ban on public gatherings and border closures. Throughout all the lockdown levels, essential services including the provision of health services, food retail shops, policing, banking and collection of social grants were not affected. Within the levels, physical distancing, hand washing and sanitising and the wearing of cloth face masks became prescribed practices in all public spaces. Within the risk-adjusted strategy, level 5 comprised the most stringent restrictions with level 1 comprises the least stringent restrictions. The objectives of each alert level are12 :

In alert level 5, severe measures were put in place to contain the spread of COVID-19 and to prevent COVID-19 mortalities;

In alert level 4, extreme precautionary measures were put in place to limit community transmission while allowing some economic activities to resume.

In alert level 3, there were restrictions on numerous activities, such as at workplaces and social engagements in order to minimise high transmission risks;

In alert level 2, physical distancing measures and restrictions on leisure activities were put in place to prevent a COVID-19 resurgence

In alert level 1, most normal activities may resume provided that precautionary measures are in place and health guidelines are followed—focusing largely on the use of masks, physical distancing and frequent hand washing.

By 30 September 2020, South Africa was in level 1. The best practices identified in the creation and implementation of the risk-adjusted strategy included strong multistakeholder collaborations and rapid and decisive actions taken to mobilise the appropriate resources. A challenge was the suboptimal coordination between National and Provincial IMTs. Another challenge was achieving a balance between reducing the economic hardships associated with the alert levels and preventing the rapid spread of COVID-19.

Capacity building

Due to the early national lockdown, there was an opportunity to increase the capacity of the health system. A surge strategy was developed, and provinces were engaged to align the strategy within the specific provincial context. Models were developed to estimate the capacity that would be required at the peak of the epidemic, these estimates included the number of hospital beds, nurses, doctors, community health workers, isolation facilities, medical equipment, oxygen and personal protective equipment (PPE) that would be required. Healthcare staff were repurposed and trained to ensure there was sufficient knowledge of the specific care that patients with COVID-19 would require. A demand forecast for medicines was developed and constantly updated, aligned to the epidemiological profile and new clinical research and experience. The supply of oxygen was scaled up to align with the projected bed utilisation and quarantine facilities were constructed. Furthermore, the Stock Visibility System was expanded to include monitoring of PPEs at all levels of healthcare, and a governance system was established to oversee the PPE and medicine supply chain.

Challenges included the delayed approval of the surge strategy and the absence of a single integrated information system at hospital level that could be used to track demand and guide the supply of the appropriate healthcare services; confusion surrounding the multiple different forecasting models in circulation and supplier’s inability to meet the sudden increase in demand. PPE procurement was a major challenge as South Africa was competing with the rest of the world for limited supplies; in addition, there was a limited number of available flights able to transport stock of PPE. There were further challenges surrounding PPE procurement, with corruption leading to disreputable manufacturers being awarded tenders in provinces at inflated prices.

Contact tracing and community screening

Within the community screening and contact tracing strategy, the major strength identified was the use of community health workers. Data were used to pinpoint hotspots, and contact tracing teams were deployed into these areas. There was further success using digital contact tracing applications—one such application used by contact tracers is COVID-Connect. The COVID-Connect system enables individuals who have undergone COVID-19 testing to receive their laboratory results via WhatsApp or short message service. The use of educational material was beneficial when tracers or screeners visited households as it facilitated engagement with the members of the household.

Challenges arose when there was a steep increase in the number of COVID-19 cases over a short period of time as there were insufficient contact tracers and case investigators to support contact tracing. The manual reporting of the screening data led to delays, which in turn impeded the ability of districts to respond to outbreaks in a timeous manner. Furthermore, the community screening elicited many possible cases being referred for testing while the laboratories did not have sufficient capacity to test and process the tests in a timely manner; this led to increased backlogs and long turnaround times.

Discussion

The strengthened command and control through centralised and decentralised IMTs enabled swift evidenced-based decision-making. The timely and technologically innovative contact tracing and large-scale community screening and testing were beneficial in quickly detecting hotspots and mitigating further spread. Public and private sector collaborations enabled efficient capacity scale-up in some areas. The provision of isolation and quarantine facilities and the freeing up of hospital beds for patients with COVID-19 enabled the provision of surge capacity, however, this also resulted in primary healthcare services being neglected. The Ministerial Advisory Committees comprising of various subject matter experts, provided the Minister of Health with evidence-based advice on managing the pandemic. While the early stringent lockdown provided South Africa with valuable time to increase healthcare capacity, it has also resulted in economic hardships, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. Another important lesson learnt was the need for continuous oversight and accountability among leaders and the need for strong governance systems to avoid corruption.

Conclusion

Taking into account the challenges experienced and lessons learnt during the first surge of COVID-19 cases in South Africa, there are various aspects that might have been done differently. Improvements would include the development of a more agile and targeted approach to risk communication and community engagement; rapidly rolling out community screening and contact tracing, coupled with educational material covering the importance of these interventions; the implementation of more effective enforcement strategies covering the enforcement of social distancing, hand hygiene and the proper use of masks; increase public and private sector cooperations; implement an electronic medical record and a single information system for the healthcare sector and allocate more finances to the development and hiring of human resources for health. As South Africa moves into the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is vital that the lessons learnt during the first surge are leveraged to improve the public health response.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: DM and YP conceptualised the manuscript. The other authors as part of the South African Incident Management Team contributed to the text within, reviewing and finalising the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository;

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Statement on the second meeting of the International health regulations (2005) emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), 2005. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 2. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus . WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020, World Health Organization. Available: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020 [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 3. World Health Organization, . Framework for a public health emergency operations centre. World Health organization, Geneva, 2015. Available: www.who.int/about/licensing/ [Accessed 08 Sep 2020].

- 4. Mkhize Z. Minister Zweli Mkhize reports first case of coronavirus Covid-19 | South African government, South African government media statement, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.za/speeches/health-reports-first-case-covid-19-coronavirus-5-mar-2020-0000 [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 5. Statistics South Africa . 2020 Mid-year population estimates | statistics South Africa, department of statistics South Africa. Available: http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13453 [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 6. South African Government, . South Africa’s provinces, 2019. Available: https://www.gov.za/about-sa/south-africas-provinces [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 7. Mahlathi P, Dlamini J. Minimum Data Sets for Human Resources for Health and the Surgical Workforce in South Africa’s Health System, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dlamini Zuma N. Declaration of a national state of disaster, government Gazette, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202003/43096gon313.pdf [Accessed 09 Sep 2020].

- 9. South African National Department of Health . Update on Covid-19 (04th September 2020), SA corona virus online portal, 2020. Available: https://sacoronavirus.co.za/2020/09/04/update-on-covid-19-04th-september-2020/ [Accessed 12 Sep 2020].

- 10. Africa CDC . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 2020. Available: https://africacdc.org/covid-19/ [Accessed 12 Sep 2020].

- 11. National Department of Health . National Plan for COVID-19 Health Response: South Africa.” Pretoria

- 12. South African Government . About alert system, 2020. Available: https://www.gov.za/covid-19/about/about-alert-system [Accessed 19 Sep 2020].