Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence of burn-out syndrome in healthcare workers working on the front line (FL) in Spain during COVID-19.

Design

Cross-sectional, online survey-based study.

Settings

Sampling was performed between 21st April and 3rd May 2020. The survey collected demographic data and questions regarding participants’ working position since pandemic outbreak.

Participants

Spanish healthcare workers working on the FL or usual ward were eligible. A total of 674 healthcare professionals answered the survey.

Main outcomes and measures

Burn-out syndrome was assessed by the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Medical Personnel.

Results

Of the 643 eligible responding participants, 408 (63.5%) were physicians, 172 (26.8%) were nurses and 63 (9.8%) other technical occupations. 377 (58.6%) worked on the FL. Most participants were women (472 (73.4%)), aged 31–40 years (163 (25.3%)) and worked in tertiary hospitals (>600 beds) (260 (40.4%)). Prevalence of burn-out syndrome was 43.4% (95% CI 39.5% to 47.2%), higher in COVID-19 FL workers (49.6%, p<0.001) than in non- COVID-19 FL workers (34.6%, p<0.001). Women felt more burn-out (60.8%, p=0.016), were more afraid of self-infection (61.9%, p=0.021) and of their performance and quality of care provided to the patients (75.8%, p=0.015) than men. More burn-out were those between 20 and 30 years old (65.2%, p=0.026) and those with more than 15 years of experience (53.7%, p=0.035).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that, working on COVID-19 FL (OR 1.93; 95% CI 1.37 to 2.71, p<0.001), being a woman (OR 1.56; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.29, p=0.022), being under 30 years old (OR 1.75; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.89, p=0.028) and being a physician (OR 1.64; 95% CI 1.11 to 2.41, p=0.011) were associated with high risk of burn-out syndrome.

Conclusions

This survey study of healthcare professionals reported high rates of burn-out syndrome. Interventions to promote mental well-being in healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 need to be immediately implemented.

Keywords: public health, COVID-19, anxiety disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was conducted in the middle and late stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, 2 weeks after the peak of the curve was reached in Spain, mainly in a critically epidemic affected area, which was Madrid Community. To our knowledge, this is the first report on burn-out prevalence and associated risk factors among healthcare workers in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The results show a substantial proportion of burn-out among healthcare workers in the front lines, particularly among young women and physicians, are in line with previous reports from China and Italy.

The main limitation of our study is that it is an online voluntary response survey distributed by mailing lists and social networks. Being voluntary, those professionals most affected may be more interested in answering the survey, so the degree of burn-out prevalence may be overestimated; still, the large number of survey responses may have mitigated this effect.

This study was limited in scope. Most participants (81.2%) were from Madrid Community, limiting the generalisation of our findings to less affected regions. Additionally, the study was performed during 2 weeks and lacks longitudinal follow-up.

Introduction

The current pandemic by the highly contagious novel coronavirus named SARS-CoV-2 started in Wuhan (China)1 2 and has rapidly spread worldwide. In May 2020, Spain became Europe’s next epicentre of the contagion and was the second country worldwide most severely affected by the COVID-19 after the USA.3 Of note, out of its confirmed coronavirus cases, more than 20% correspond to healthcare professionals, the highest number worldwide.4

This critical situation was faced by healthcare workers on the COVID-19 front line (FL), who were directly involved in the treatment, diagnosis and care of patients with SARS-CoV-2, who responded with a display of selflessness, caring for patients despite the risk of infection. The mounting daily number of confirmed and suspected cases, the overwhelming workload, the shortage of personal protection equipment and lack of effective treatment, may all contribute to the physical and psychological burden of these healthcare professionals. Previous studies on the 2003 SARS outbreak reported adverse psychological impact among healthcare workers5 6 who reported experiencing high levels of stress, anxiety and depression symptoms, which could have long-term psychological outcomes.7 8 This feeling is what is known as ‘burn-out syndrome’, a feeling which already affected healthcare professionals, especially physicians, meaning that when COVID-19 kicked in, they were already burn-out.9 10

Burn-out is a syndrome conceptualised as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed and three dimensions characterise it: feelings of emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (DP) and a low feeling of personal accomplishment (PA).9 Its prevalence is high among the different groups of healthcare professionals, and is usually higher in physicians.10 11

In order to quantify this type of stress, there are numerous scales available; the most validated one to assess the incidence of burn-out in healthcare personnel being the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), considered the gold standard.12

This pandemic context has generated a turmoil of all these feelings and emotions in the healthcare professionals in a very short period of time that may have a substantial negative mental health outcome, which is why this kind of study has become of utter importance.13 The main goal of our study was to evaluate the burn-out prevalence of healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic and evaluate the differences between professionals working on the FL versus those working in their usual wards. Secondarily, we aimed at comparing burn-out proportions between working on the FL vs working at the usual ward, and finally compared the prevalence of burn-out syndrome during COVID-19 pandemic and pre-COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

The study is a cross-sectional online survey sampling between 21st April 2020 and 3rd May 2020, the 2 weeks following the COVID-19 contagion peak in Spain. During this period, the total confirmed cases of COVID-19 exceeded 60 000 in Madrid and over 200 000 in Spain. The survey included 15 demographic questions and questions regarding participants’ status in the past 2 months since pandemic outbreak. It also included the MBI-Medical Personnel to measure burn-out, which is a 22-question survey that has been frequently used in other studies examining burn-out in healthcare workers, including physicians and nurses (find the complete survey online here: https://forms.gle/nV1JBRHjiEBiV5TeA).

Approval from the clinical research ethics committee of Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda University Hospital was received before the initiation of this study. The dissemination of the survey was conducted through different national healthcare system email registries and social networks (Instagram and Twitter), with the aim of comparing the differences between working with COVID-19 patients or at the usual wards among healthcare workers in Spain. Because of the self-selected nature of the sample, neither invitations nor response rates could be quantifiable, as reported by American Association for Public Opinion Research reporting guideline. Because Madrid Community was most severely affected, the sample in this region is considerably higher.

Being a voluntary survey, response bias may exist if those professionals most affected may be more interested in answering the survey, or on the contrary, were either too stressed to respond, or not stressed at all and therefore may have not been interested in answering the survey. Still, the large number of survey responses and the calculation of the needed sample size may have mitigated this effect.

Patient and public involvement

The survey was sent as an online questionnaire to healthcare professionals practising in Spain, who had been actively working during COVID-19 pandemic. Study population comprised physicians, nurses, nursing assistants and emergency healthcare technicians. A link to an online survey was disclosed through dissemination emails and social networks among the healthcare professionals. Participants were asked about their working position, engagement in clinical activities of diagnosing and treating patients with symptoms or patients with confirmed COVID-19, or if they had stayed in their usual wards. The survey was anonymous, and confidentiality of information was assured. It consisted of the following sections:

Sociodemographic variables and working conditions during pandemic: age, gender, marital status, autonomous community of work, occupation, type of hospital, working position (COVID-19 FL or usual ward), medical specialty, practising years, weekly hours worked and weekends worked.

MBI: consists of 22 questions; responses are rated depending on the degree of agreement or disagreement with the statement. The questions refer to the degree of EE (nine questions), DP (five questions) and personal accomplishment (eight questions). It is defined as burn-out syndrome to have a high percentile of EE, and/or a high percentile of DP and/or a low percentile of personal achievement. The MBI is the gold standard for evaluating burn-out syndrome.12 13 The median (IQR) scores on the classification of burn-out syndrome were defined as high level of EE 26,2 (ranged 20–32) and/or high level of DP 11,6 (ranged 9–14) and low level of PA 29,6 (ranged 26–34).

Attitude of healthcare workers toward COVID-19 pandemic (self-assessment): six questions rated from 1 to 5 to evaluate participant’s attitude towards (1) psychological impact, (2) self-infection, (3) risk of infecting their family, (4) this pandemic going for too long, (5) patients outcome, and (6) their performance and quality of care.

Outcomes and covariates

The main outcome was to assess prevalence of burn-out syndrome in FL workers. Secondarily, to compare burn-out proportions between working on the FL versus working at usual ward and a comparison of prevalence of burn-out syndrome in healthcare personnel during COVID-19 pandemic and pre-COVID-19.

Study size

The proportion of healthcare workers with burn-out syndrome was estimated between 35% and 38.7% in several studies before COVID-19 pandemic.10 14 15 To achieve 4% precision in estimating a proportion using a 95% bilateral asymptotic CI, assuming the proportion is 35%, it was necessary to include 547 participants in the study.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed expressing the categorical variables in number and percentage, and the quantitative variables in mean and IQR.

Wald’s asymptotic method was used to estimate the prevalence of burn-out syndrome in the sample and its 95% CI, as well as to estimate the proportions of burn-out syndrome in COVID-19 FL workers and non-COVID-19 FL workers.

A descriptive analysis of MBI‘s quantitative variables was performed for Maslach items calculating their medians and 25 and 75 percentiles. To proceed to the calculation or classification of burn-out syndrome, the groups low (=p25 percentile), medium (=p50 percentile), severe/high (=p75 percentile) of each of the Maslach items were defined.

The association between categorical variables was initially analysed with a χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test when expected n<5).

Subsequently, a logistic regression model was designed to measure the association of working in the COVID-19 FL on the diagnosis of burn-out. The final model decision took into account statistical criteria as well as researchers’ criteria. The associated variables resulting from this model are expressed as OR with a 95% CI. The association of the responses of the different Maslach items with the exposure to work in the COVID-19 environment was performed using a univariate logistic regression. This relationship is expressed as an OR with a 95% CI and a p<0.05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed using Stata statistical software V.16 (StataCorp).

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 674 healthcare professionals answered the survey. Out of these 674, 31 were excluded for the following reasons: 15 were duplicate answers, 6 were previous tests of the survey, 2 did not answer their working position (COVID-19 FL or non-COVID-19 FL) and 8 were non healthcare profiles (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of healthcare workers (n (%))

| Characteristics | Total n (%) | COVID-19 frontline | Non-COVID-19 front line |

| Overall | 643 (100) | 377 (58.63) | 266 (41.37) |

| Sex | |||

| Women | 472 (73.41) | 290 (76.92) | 182 (68.42) |

| Men | 171 (26.59) | 87 (23.08) | 84 (31.58) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–30 | 115 (17.88) | 81 (21.49) | 34 (12.78) |

| 31–40 | 163 (25.35) | 98 (25.99) | 65 (24.44) |

| 41–50 | 151 (23.48) | 87 (23.08) | 64 (24.06) |

| 51–60 | 160 (24.88) | 84 (22.28) | 76 (28.57) |

| 61–70 | 53 (8.24) | 27 (7.16) | 26 (9.77) |

| >70 | 1 (0.16) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.38) |

| Marriage status | |||

| Married | 491 (76.36) | 284 (75.33) | 207 (77.82) |

| Unmarried | 152 (23.64) | 93 (24.67) | 59 (22.18) |

| Occupation | |||

| Physician | 408 (63.45) | 214 (56.76) | 194 (72.93) |

| Nurse | 172 (26.75) | 121 (32.10) | 51 (19.17) |

| Other | 63 (9.80) | 42 (11.14) | 21 (7.89) |

| Specialty | |||

| Unspecified | 27 (4.20) | 22 (5.84) | 5 (1.88) |

| EMS (out-of-hospital EMS care) | 128 (19.91) | 101 (26.79) | 27 (10.15) |

| Medical | 406 (63.14) | 213 (56.50) | 193 (72.56) |

| Surgical | 82 (12.75) | 41 (10.88) | 41 (15.41) |

| Type of hospital (no of beds) | |||

| Primary care | 123 (19.13) | 90 (23.87) | 33 (12.41) |

| <300 | 106 (16.49) | 68 (18.04) | 38 (14.29) |

| 300–600 | 154 (23.95) | 77 (20.42) | 77 (28.95) |

| >600 | 260 (40.44) | 142 (37.67) | 118 (44.36) |

| Years of experience | |||

| ≤5 | 119 (18.51) | 82 (21.75) | 37 (13.91) |

| 6–10 | 82 (12.75) | 52 (13.79) | 30 (11.28) |

| 11–15 | 83 (12.91) | 41 (10.88) | 42 (15.79) |

| >15 | 359 (55.83) | 202 (53.58) | 157 (59.02) |

| Average weekly working hours | |||

| <10 | 7 (1.09) | 5 (1.33) | 2 (0.75) |

| 11–20 | 23 (3.58) | 13 (3.45) | 10 (3.76) |

| 21–40 | 236 (36.70) | 110 (29.18) | 126 (47.37) |

| 41–60 | 290 (45.10) | 185 (49.07) | 105 (39.47) |

| 61–80 | 62 (9.64) | 44 (11.67) | 18 (6.77) |

| >80 | 25 (3.89) | 20 (5.31) | 5 (1.88) |

| Weekends worked during pandemic | |||

| Never | 138 (21.46) | 28 (7.43) | 110 (41.35) |

| Every 2 weeks | 260 (40.44) | 151 (40.05) | 109 (40.98) |

| Every week (1 day) | 177 (27.53) | 141 (37.40) | 36 (13.53) |

| Every week (2 days) | 68 (10.58) | 57 (15.12) | 11 (4.14) |

Of the 643 responding participants, 408 (63.5%) were physicians, 172 (26.8%) were nurses and 63 (9.8%) corresponded to other healthcare occupations such as radio diagnostic technicians or nurse assistants. Of the participants, 422 (66%) worked in the Madrid Community, 377 (58.63%) worked on the FL and 266 (41.37%) in their usual ward.

Most participants were women (472 (73%)), were aged 31–40 years (163 (25%)), and 51–60 (160 (25%)), 76% had a partner, and worked in tertiary hospitals (260 (40%)). Among the participants’ specialties, 63% were Medical, 20% out-of-hospital Emergency Medical Services care (EMS) and 13% were Surgical (table 1).

A total of 377 participants (59%) were FL healthcare workers directly engaged in diagnosing, treating, or caring for patients with or suspected of COVID-19. Regarding this FL group, mostly were women, aged 30–41 years, married and physicians. The two predominant specialties working in the FL were Medical and EMS, and no differences were observed between FL and usual ward in the surgical specialty. FL workers mostly worked in tertiary hospitals (>600 beds) or Primary Care (the latter were sent to attend at field hospitals). The majority of FL workers had more than 15 years of experience, worked from 41 to 60 hours per week and had worked during weekends at least once a week or every 2 weeks during pandemic (table 1).

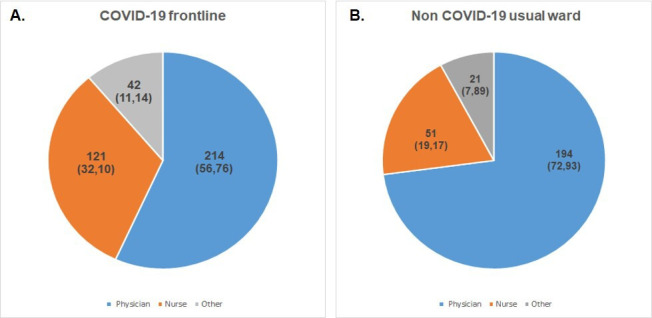

Of note, regarding the working position of the surveyed participants (figure 1), a total of 214 (56.7%) healthcare workers working in FL were physicians, 121 (32%) were nurses and 42 (11.1%) other healthcare occupations, whereas those who stayed at their usual wards were 194 (72%) physicians, 51 (19%) nurses and 21 (8%) other healthcare occupations.

Figure 1.

Distribution of occupations (physicians, nurses, others) in COVID-19 frontline (A) versus Non COVID-19 usual ward (B).

Attitudes toward COVID-19

Participants were asked about their attitude towards the effect of COVID-19 (table 2A, 2B). The main difference observed was that 57.5% of healthcare workers reported a higher burn-out level now than prepandemic, 60% of the surveyed professionals were afraid of becoming infected at work, 83% were afraid of greatly increasing the risk of infection to their families, while 89% feared for this pandemic going on for too long. Around 85% of the surveyed healthcare workers were worried about their patient’s outcome and 73% were worried about providing correct practice and quality of care. Compared with non-FL, FL healthcare workers (61.5%, p<0.001) felt more burn-out now than before the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, women felt more burn-out now than prepandemic (60.8%, p=0.016), were more afraid of self-infection (61.9%, p=0.021) and of their performance and quality of care provided to the patients (75.8%, p=0.015) than men. Of note, the segment of age who felt more burn-out now than prepandemic were those between 20 and 30 years old (65.2%, p=0.026).

Table 2A.

Attitude of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 (n (%))

| Characteristics | Total n (%) | COVID-19 frontline | Non- COVID-19 frontline | P value | Age (yrs) | P value | Sex | P value | ||||

| 20–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | Women | Men | |||||||

| I feel more burn-out now than compared with before COVID-19 crisis | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 370 (57.55) | 232 (61.54) | 138 (51.88) | 75 (65.22) | 98 (60.12) | 82 (54.30) | 88 (55.00) | 287 (60.81) | 83 (48.54) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 120 (18.66) | 77 (20.42) | 43 (16.17) | <0.001 | 23 (20.00) | 35 (21.47) | 28 (18.54) | 22 (13.75) | 0.026 | 84 (17.80) | 36 (21.05) | 0.016 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 153 (23.79) | 68 (18.04) | 85 (31.95) | 17 (14.78) | 30 (18.40) | 41 (27.15) | 50 (31.25) | 101 (21.40) | 52 (30.41) | |||

| I am worried about being infected | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 384 (59.72) | 218 (57.82) | 166 (62.41) | 62 (53.91) | 98 (60.12) | 91 (60.26) | 94 (58.75) | 292 (61.87) | 92 (53.80) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 126 (19.60) | 81 (21.49) | 45 (16.92) | 0.33 | 25 (21.74) | 25 (15.34) | 37 (24.50) | 33 (20.63) | 0.244 | 95 (20.13) | 31 (18.13) | 0.021 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 133 (20.69) | 78 (20.69) | 55 (20.67) | 28 (24.35) | 40 (24.54) | 23 (15.23) | 33 (20.63) | 85 (18.01) | 48 (28.07) | |||

| I am worried about infecting my family | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 538 (83.67) | 318 (84.35) | 220 (82.70) | 100 (86.96) | 142 (87.12) | 128 (84.77) | 124 (77.50) | 403 (85.38) | 135 (78.95) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 51 (7.93) | 28 (7.43) | 23 (8.65) | 0.82 | 8 (6.96) | 7 (4.29) | 13 (8.61) | 19 (11.88) | 0.419 | 34 (7.20) | 17 (9.94) | 0.146 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 54 (17.07) | 31 (8.22) | 23 (8.65) | 7 (6.09) | 14 (8.59) | 10 (6.62) | 17 (10.63) | 35 (7.42) | 19 (11.11) | |||

| I am worried this pandemic goes on for too long | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 573 (89.11) | 334 (88.60) | 239 (89.85) | 104 (90.43) | 149 (91.41) | 131 (86.75) | 143 (89.38) | 427 (90.47) | 146 (85.38) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 42 (6.53) | 22 (5.84) | 20 (7.52) | 0.15 | 6 (5.22) | 7 (4.29) | 15 (9.93) | 7 (4.38) | 0.294 | 28 (5.93) | 14 (8.19) | 0.161 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 28 (4.36) | 21 (5.57) | 7 (2.63) | 5 (4.35) | 7 (4.29) | 5 (3.31) | 10 (6.25) | 17 (3.60) | 11 (6.43) | |||

| I am worried about my patient’s outcome | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 546 (84.91) | 323 (85.68) | 223 (83.84) | 96 (83.48) | 138 (84.66) | 125 (82.78) | 141 (84.91) | 404 (85.59) | 142 (83.04) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 77 (11.98) | 43 (11.41) | 34 (12.78) | 0.81 | 18 (15.65) | 18 (11.04) | 22 (14.57) | 5 (9.43) | 0.607 | 54 (11.44) | 23 (13.45) | 0.727 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 20 (3.11) | 11 (2.92) | 9 (3.38) | 1 (0.87) | 7 (4.29) | 4 (2.65) | 3 (5.66) | 14 (2.97) | 6 (3.51) | |||

| I am worried for my performance and quality of care provided | ||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 471 (73.25) | 288 (76.39) | 183 (68.80) | 91 (79.13) | 124 (76.07) | 115 (76.16) | 109 (68.13) | 358 (75.84) | 113 (66.08) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 84 (13.06) | 44 (11.67) | 40 (15.04) | 0.09 | 11 (9.57) | 18 (11.04) | 21 (13.91) | 24 (15.00) | 0.207 | 60 (12.71) | 24 (14.04) | 0.015 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 88 (13.68) | 45 (11.94) | 43 (16.17) | 13 (11.30) | 21 (12.88) | 15 (9.93) | 27 (16.88) | 54 (11.44) | 34 (19.88) | |||

Table 2B.

Attitude of healthcare workers toward COVID-19 (n (%))

| Characteristics | Type of hospital (no of beds) | P value | Years of experience | P value | Average weekly working hours | P value | |||||||||

| <300 | 300–600 | >600 | Primary care | ≤5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | >15 | ≤20 | 21–40 | 41–60 | >60 | ||||

| I feel more burn-out now than compared with before COVID-19 crisis | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 65 (61.62) | 83 (53.90) | 148 (56.92) | 74 (60.16) | 75 (63.03) | 50 (60.98) | 52 (62.65) | 193 (53.76) | 14 (46.67) | 129 (54.66) | 174 (60.00) | 53 (60.92) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 21 (19.81) | 34 (22.08) | 42 (16.15) | 23 (18.70) | 0.516 | 21 (17.65) | 21 (25.61) | 15 (18.07) | 63 (17.55) | 0.035 | 10 (33.33) | 47 (19.92) | 49 (16.90) | 14 (16.09) | 0.379 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 20 (18.87) | 37 (24.03) | 70 (26.92) | 26 (21.14) | 23 (19.33) | 11 (13.41) | 16 (19.28) | 103 (28.69) | 6 (20.00) | 60 (25.42) | 67 (23.10) | 20 (22.99) | |||

| I am worried about being infected | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 69 (65.09) | 87 (56.49) | 141 (54.23) | 87 (70.73) | 66 (55.46) | 42 (51.22) | 58 (69.88) | 218 (60.72) | 23 (76.67) | 152 (64.41) | 175 (60.34) | 34 (39.08) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 19 (17.92) | 30 (19.48) | 53 (20.38) | 24 (19.51) | 0.013 | 23 (19.33) | 18 (21.95) | 9 (10.84) | 76 (21.17) | 0.098 | 3 (10.00) | 42 (17.80) | 58 (20.00) | 23 (26.44) | 0.001 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 18 (16.98) | 37 (24.03) | 66 (25.38) | 12 (9.76) | 30 (25.21) | 22 (26.83) | 16 (19.28) | 65 (18.11) | 4 (13.33) | 42 (17.80) | 57 (19.66) | 30 (34.48) | |||

| I am worried about infecting my family | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 98 (92.95) | 122 (79.22) | 213 (81.92) | 105 (85.37) | 102 (85.71) | 69 (84.15) | 75 (90.36) | 292 (81.34) | 28 (93.33) | 193 (81.78) | 251 (86.55) | 66 (75.86) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 4 (3.77) | 13 (8.44) | 25 (9.62) | 9 (7.32) | 0.103 | 9 (7.56) | 5 (6.10) | 3 (3.61) | 34 (9.47) | 0.477 | 0 (0.00) | 21 (8.90) | 19 (6.55) | 11 (12.64) | 0.059 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 4 (3.77) | 19 (12.34) | 22 (8.46) | 9 (7.32) | 8 (6.72) | 8 (9.76) | 5 (6.02) | 33 (9.19) | 2 (6.67) | 22 (9.32) | 20 (6.90) | 10 (11.49) | |||

| I am worried this pandemic goes on for too long | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 98 (92.45) | 137 (88.96) | 229 (88.08) | 109 (88.62) | 104 (87.39) | 76 (92.68) | 78 (93.98) | 315 (87.74) | 29 (96.67) | 216 (91.53) | 255 (87.93) | 73 (83.91) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 5 (4.72) | 11 (7.14) | 16 (6.15) | 10 (8.13) | 0.743 | 8 (6.72) | 2 (2.44) | 4 (4.82) | 28 (7.80) | 0.379 | 0 (0.00) | 16 (6.78) | 20 (6.90) | 6 (6.90) | 0.068 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 3 (2.83) | 6 (3.90) | 15 (5.77) | 4 (3.25) | 7 (5.88) | 4 (4.88) | 1 (1.20) | 16 (4.46) | 1 (3.33) | 4 (1.69) | 15 (5.17) | 8 (9.20) | |||

| I am worried about my patient’s outcome | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 90 (84.91) | 128 (83.12) | 220 (84.62) | 108 (87.80) | 97 (81.51) | 69 (84.15) | 73 (87.95) | 307 (85.52) | 24 (80.00) | 206 (87.29) | 240 (82.76) | 76 (87.36) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 11 (10.38) | 21 (13.64) | 32 (12.31) | 13 (10.57) | 0.839 | 20 (16.81) | 8 (9.76) | 10 (12.05) | 39 (10.86) | 0.156 | 4 (13.33) | 24 (10.17) | 40 (13.79) | 9 (10.34) | 0.69 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 5 (4.72) | 5 (3.25) | 8 (3.08) | 2 (1.63) | 2 (1.68) | 5 (6.10) | 0 (0.00) | 13 (3.62) | 2 (6.67) | 6 (2.54) | 10 (3.45) | 2 (2.30) | |||

| I am worried for my performance and quality of care provided | |||||||||||||||

| Agree/strongly agree | 83 (78.30) | 110 (71.43) | 188 (72.31) | 90 (73.17) | 92 (77.31) | 60 (73.17) | 68 (81.93) | 251 (69.92) | 20 (66.67) | 184 (77.97) | 200 (68.97) | 67 (77.01) | |||

| Neither agree or disagree | 11 (10.38) | 24 (15.58) | 34 (13.08) | 15 (12.20) | 0.856 | 11 (9.24) | 10 (12.20) | 9 (10.84) | 54 (15.04) | 0.277 | 2 (6.67) | 24 (10.17) | 51 (17.59) | 7 (8.05) | 0.022 |

| Disagree/strongly disagree | 12 (11.32) | 20 (12.99) | 38 (14.62) | 18 (14.63) | 16 (13.45) | 12 (14.63) | 6 (7.23) | 54 (15.04) | 8 (26.67) | 28 (11.86) | 39 (13.45) | 13 (14.94) | |||

Regarding the type of hospital, those healthcare workers working in small hospitals (<300 beds) were the ones more worried over becoming infected (65%, p=0.013). Also reporting a higher burn-out level now than prepandemic (53.7%, p=0.035) were those healthcare workers with more than 15 years of experience. Additionally, overworked healthcare workers (>60 working hours per week) were more afraid of their performance and quality of care (70%, p=0.022) and those not overworked (<20 working hours per week) were more afraid of becoming infected (39%, p=0.001). Factors such as occupation, marital status, specialty or weekends worked during the pandemic had no significance in the attitude towards COVID-19.

Burn-out prevalence and its association with working position: MBI

Results on the MBI are detailed in table 3, where burn-out prevalence and its association with working positions (COVID-19 FL vs non COVID-19 FL) have been calculated. We found that the prevalence of burn-out syndrome in our sample is 43.4% (95% CI 39.5% to 47.2%), and the frequency of working in COVID-19 FL with developing burn-out syndrome is higher in COVID-19 FL workers (49.6%, p<0.001) than in non- COVID-19 FL workers (34.6%, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Results Maslach Burnout Inventory

| Total N (%) |

COVID-19 frontline | Non-COVID-19 frontline | P value | |

| Emotional exhaustion | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 149 (23.17) | 65 (43.62) | 84 (56.38) | |

| Intermediate | 340 (52.88) | 202 (59.41) | 138 (40.59) | |

| High | 154 (23.95) | 110 (71.43) | 44 (28.57) | |

| Depersonalisation | 0.006 | |||

| Low | 154 (23.95) | 78 (50.65) | 76 (49.35) | |

| Intermediate | 356 (55.37) | 207 (58.15) | 149 (41.85) | |

| High | 133 (20.68) | 92 (69.17) | 41 (30.83) | |

| Personal accomplishment | 0.078 | |||

| Low | 147 (22.86) | 90 (61.22) | 57 (38.78) | |

| Intermediate | 364 (56.61) | 221 (60.71) | 143 (39.29) | |

| High | 132 (20.53) | 66 (50.00) | 66 (50.00) | |

| Burn-out syndrome | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 279 (43.39) | 187 (49.60) | 92 (34.59) | |

| No | 364 (56.61) | 190 (50.40) | 174 (65.41) |

The description of Maslach items shows a significant association with high levels of EE (p<0.001) and high levels of DP (p=0.006) with working on the COVID-19 FL, but not with PA.

Associated factors to burn-out syndrome

The potential risk factors associated through the univariate study with burn-out syndrome are shown in table 4; working on the COVID-19 FL (OR 1.86; 95% CI 1.35 to 2.57; p<0.001), age between 20 and 30 years old compared with 31–40 (OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.91; p=0.019) and to 51–60 years old (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.79; p=0.003), female sex (OR 1.50; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.15; p=0.029) and occupation category (being physician or nurse doubles the risk of burn-out syndrome compared with ‘others’). Being unexperienced (under 5 years of working experience) was also related to a higher risk of burn-out syndrome compared with more experienced workers with over 15 years of practice.

Table 4.

Univariable analysis

| Characteristics | (OR 95% CI) | P value |

| Working position | ||

| COVID-19 front line | 1.86 (1.35 to 2.57) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–30 (reference category) | ||

| 31–40 | 0.56 (0.35 to 0.91) | 0.019 |

| 41–50 | 0.73 (0.45 to 1.19) | 0.21 |

| 51–60 | 0.48 (0.30 to 0.79) | 0.003 |

| 61–70 | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.97) | 0.041 |

| Sex | ||

| Men (reference category) | ||

| Women | 1.50 (1.04 to 2.15) | 0.029 |

| Occupation | ||

| Other (reference category) | ||

| Nurse | 2.02 (1.06 to 3.84) | 0.033 |

| Physician | 2.64 (1.45 to 4.80) | 0.002 |

| How long have you been practising? (years) | ||

| ≤5 (reference category) | ||

| 6–10 | 0.66 (0.37 to 1.16) | 0.154 |

| 11–15 | 0.58 (0.33 to 1.03) | 0.066 |

| >15 | 0.62 (0.41 to 0.94) | 0.026 |

Factors associated with burn-out syndrome.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (table 5) revealed that, working in COVID-19 FL, being a woman under 30 years old, and being a physician were the main factors associated with high risk of burn-out syndrome.

Table 5.

Multivariable analysis

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Working position | ||

| COVID-19 frontline | 1.93 (1.37 to 2.71) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 1.56 (1.06 to 2.29) | 0.022 |

| Occupation | ||

| Physician | 1.64 (1.11 to 2.41) | 0.011 |

| Other | 0.54 (0.27 to 1.05) | 0.0022 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 31–40 | 0.62 (0.38 to 1.03) | 0.066 |

| 41–50 | 0.90 (0.54 to 1.50) | 0.709 |

| 51–60 | 0.57 (0.34 to 0.94) | 0.028 |

| 61–70 | 0.61 (0.30 to 1.22) | 0.166 |

Risk factors associated with burn-out syndrome.

Discussion

Despite Spain’s image being one of the healthiest nations in the world, having a robust universal healthcare system, and the highest life expectancy in the European Union, the COVID-19 pandemic has severely tested the Spanish health system resilience and pandemic preparedness. The Spanish health system was already fragile when it was overwhelmed by COVID-19 in March, after a decade of austerity that followed the 2008 financial crisis, which left health services understaffed, under-resourced and under strain.

The creation in 2004 of a Centre for Coordination of Health Alerts and Emergency, and the tightly calculated design of the Spanish healthcare system were supposed to ensure that threatening illnesses were quickly detected and treated. Nevertheless, the pandemic laid bare the country’s poor coordination among central and regional authorities, the weak surveillance systems and scarcity of personal protective equipment and critical care equipment, or an ageing population and vulnerable disease groups, among other problems.16

With as many as 65 000 healthcare workers infected, health facilities in the worst affected regions such as Madrid or Catalonia were struggling with inadequate intensive care capacity and an insufficient number of ventilators in particular.17 Even tertiary hospitals (those with over 600 beds of capacity) cancelled non-emergency surgeries and cleared beds where possible. Policies at healthcare centres were modified in order to take some of the burden off hospitals or specialist referrals, but the steady stream of patients made them a primary source of infection. As a result, there were hardly any open consultation hours, which in turn lead to many undiagnosed diseases.

While hospitals in northern Europe are smaller and well distributed among the population, in Spain they are concentrated in the large cities. In rural areas, there is a shortage, and the hospitals available are small (under 300 beds of capacity). On top of this, Spain has just under 10 intensive care beds per 100 000 inhabitants.16

This study was conducted in the middle and late stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, 2 weeks after the peak of the curve was reached in Spain, mainly in a critically epidemic affected area, which was Madrid Community. To our knowledge, this is the first report on burn-out prevalence and associated risk factors among healthcare workers in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results show a substantial proportion of burn-out among healthcare workers in the FL, particularly among young women and physicians, are in line with previous reports from China and Italy.18 19

Healthcare workers on the FL of the healthcare response during COVID-19 pandemic have found themselves in unprecedented positions, making high-stakes decisions for patients and their own personal lives.20 21 In this context, and due not only to the elevated number of detected cases that have crowded the Spanish hospitals, especially those in the Madrid Community, but also to the grave shortages in protective gear, Spanish FL healthcare workers have defined the situation as ‘war medicine’.

The proportion of healthcare workers with psychological comorbidities was estimated at 35%, during the 2003 SARS outbreak.7 During the 2003 SARS outbreak, uncertainty and stigmatisation were prominent themes for both healthcare professionals and patients.8 This SARS-CoV-2 outbreak is no different. In this study, we report that working in COVID-19 FL doubles the risk of suffering from burn-out syndrome, compared with those professionals working in their usual wards. The other related risk factors, which are being a woman, a physician, and being under 30 years old, are related to the fact that more than 50% of the participants working on the FL were physicians, and more than 70% of the total sample were women. These results are in line with the percentage of employed women, working in the Spanish healthcare system, which is 74.2% according to the Official State Bulletin of Service of Public Administrations. According to these statistics, the most feminised group is the one under the age of 35 and the segment of women over 44 years of age represents 54.7% of the total number of practising physicians. Therefore, Medicine has 56.4% of women workers and Nursing 84.5%, according to official figures, which matches the numbers obtained in our study.

Despite being the country reporting healthcare staff accounting for the highest percentage of total infections and deaths, more than being afraid of self-infection or feeling burn-out, surveyed healthcare workers in this study reported being more worried about infecting their families (84%), of this pandemic going for too long (89%) and of their patient’s outcome (85%). Of note, a higher percentage of those participants who were more afraid of becoming infected were non COVID-19 FL workers who worked in small hospitals (<300 beds). This may be related to the unawareness that the virus might have been already among the population while patients were admitted without protective measures in place or testing in any hospital22 and only those patients coming from Wuhan or Italy were being tested. This may have provoked that medical staff working without adequate protection may have acted like vectors. In fact, infection rates in the more well protected ICU and emergency departments were lower than in general wards with no early warning of the disease.

A significant proportion of participants working on the COVID-19 FL experienced a high level of EE (71.4%), and a high level of DP (69%) compared with those working in their usual ward (28.6% and 31%, respectively). PA, another key element of burn-out, may have played a role in this pandemic scenario. COVID-19 FL workers presented lower levels of PA (61%) compared with those working in their usual ward (39%), which could relate to feeling a deeper sense of failure seeing the direct results of their care in the poor outcomes of their COVID-19 patients.

In the present study, when comparing burn-out frequency during COVID-19 pandemic to the usual burn-out ratio in the healthcare workers,14 15 23 a 4% increase in the prevalence of burn-out was observed, suggesting that during the COVID-19 pandemic the proportion of burn-out syndrome increased. Previous work has suggested that the number of years of experience, the number of hours worked per week, the frequency of working on weekends and the number of personnel in a person’s team or practice may be associated with burn-out.14 24–26 In a previous study during the acute SARS outbreak in 2003, 89% of the healthcare workers who were at high risk of exposure reported burn-out and psychological symptoms such as anxiety or depression.27

The psychological response and risk of burn-out of healthcare workers to an epidemic of infectious diseases is complicated.28 29 Sources of distress may include feelings of vulnerability or loss of control and concerns about health of self, spread of virus and its high morbidity,2 health of family and others, isolation, additionally to inadequate provision of personal protective equipment.30 Clinicians may have felt shame for thinking of themselves rather than their patients and guilt for putting their families at risk.20–22

As the current sanitary crisis ultimately abates, we cannot neglect the fact that COVID-19 is not expected to disappear in the short term or mid term, so it is mandatory for clinicians to take control of their well-being.31 An operational definition of well-being and a set of measures that provide optimum conditions to survive and prevent burn-out or any other psychological condition are needed.32 Healthcare systems must reset in order to cover the existent needs detected during COVID-19 pandemic so that we do not return to the former status quo.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was limited in scope. Most participants (81.2%) were from Madrid Community, limiting the generalisation of our findings to less affected regions. Second, the study was performed during 2 weeks and lacks longitudinal follow-up. Because of the arduous situation that it is becoming more intense every week, the psychological symptoms of healthcare workers could become more severe. Thus, these symptoms could have a long-term impact on these populations and a further investigation would be worth to perform.

The third limitation of our study is that it is an online voluntary response survey distributed by mailing lists and social networks. Being voluntary, response bias may exist if those professionals most affected may be more interested in answering the survey, or on the contrary, were either too stressed to respond, or not stressed at all and therefore may have not been interested in answering the survey; still, the large number of survey responses may have mitigated this effect.

Conclusions

This survey study of healthcare professionals working in Spanish hospitals in the FL or usual wards during COVID-19 pandemic, mainly those based in Madrid, the most hardest-hit area in the country, reported high rates burn-out syndrome. Especial interventions to promote mental well-being in healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 need to be immediately implemented, with women, physicians and FL workers requiring particular attention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the healthcare professionals that were or currently are still working heavily under very difficult circumstances and risking even their life and families during this pandemic, and took the time to answer our survey.

Footnotes

Contributors: MT: conceptualisation, study design, investigation, literature search, writing-original draft. PAS: data curation, software, supervision, writing-review and editing, methodology. AS-R: study design, data analysis. JP: software, data curation, writing-review and editing. AR: study design, data analysis, writing-review and editing. FF: investigation, literature search. AC-L: investigation, literature search. EM: data curation, writing-review and editing. MP: conceptualisation, study design, investigation, literature search, writing-review and editing, supervision, validation.

Funding: The European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme supported this study under grant agreement No 875160.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in an open access repository. Extradata are available by emailing cparejo@idiphim.org.

References

- 1.Lipsitch M, Swerdlow DL, Finelli L. Defining the Epidemiology of Covid-19 - Studies Needed. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1194–6. 10.1056/NEJMp2002125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raoult D, Zumla A, Locatelli F, et al. Coronavirus infections: epidemiological, clinical and immunological features and hypotheses. Cell Stress 2020;4:66–75. 10.15698/cst2020.04.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Map - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Available: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 4.Informe n° 32 . Situación de COVID-19 en España a 21 de mayo de 2020. Equipo COVID-19. Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

- 5.Wu Y, Wang J, Luo C, et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:e60–5. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:391–3. 10.1177/070674370404900609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ 2003;168:1245–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai Y, Lin C-C, Lin C-Y, et al. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:1055–7. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy I. [Burnout syndrome: definition, typology and management]. Soins Psychiatr 2018;39:12–19. 10.1016/j.spsy.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA 2018;320:1131–50. 10.1001/jama.2018.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev Int 2009;14:204–20. 10.1108/13620430910966406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2485–7. 10.1056/NEJMp2003149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Wolf SP, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:690–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 15.Reddy SK, Yennu S, Tanco K, et al. Frequency of burnout among palliative care physicians participating in a continuing medical education course. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:80–6. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legido-Quigley H, Mateos-García JT, Campos VR, et al. The resilience of the Spanish health system against the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e251–2. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30060-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trias-Llimós S, Bilal U. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy in Madrid (Spain). J Public Health 2020;42:635–6. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2010185. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:468–71. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:e15–16. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect 2020;105:183–7. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:686–92. 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juliá-Sanchis R, Richart-Martínez M, García-Aracil N, et al. Measuring the levels of burnout syndrome and empathy of Spanish emergency medical service professionals. Australas Emerg Care 2019;22:193–9. 10.1016/j.auec.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:1600–13. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1377–85. 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh D. Occupational risks for COVID-19 infection. Occup Med 2020;70:3–5. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fessell D, Cherniss C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and beyond: Micropractices for burnout prevention and emotional wellness. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17:746–8. 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA 2020;323:1499–500. 10.1001/jama.2020.3633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simons G, Baldwin DS. Covid-19: doctors must take control of their wellbeing. BMJ 2020;369:m1725. 10.1136/bmj.m1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heath I. Love in the time of coronavirus. BMJ 2020;369:m1801. 10.1136/bmj.m1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.