Abstract

Background

The role of combination immunomodulatory therapy with systemic corticosteroids and tocilizumab (TCZ) for aged patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome remains unclear.

Methods

A retrospective single-center study was conducted on consecutive patients aged ≥65 years who developed severe COVID-19 between 03 March and 01 May 2020 and were treated with corticosteroids at various doses (methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/12 h to 250 mg/24 h), either alone (CS group) or associated with intravenous tocilizumab (400–600 mg, one to three doses) (CS-TCZ group). The primary outcome was all-cause mortality by day +14, whereas secondary outcomes included mortality by day +28 and clinical improvement (discharge and/or a ≥2 point decrease on a 6-point ordinal scale) by day +14. Propensity score (PS)-based adjustment and inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) were applied.

Results

Totals of 181 and 80 patients were included in the CS and CS-TCZ groups, respectively. All-cause 14-day mortality was lower in the CS-TCZ group, both in the PS-adjusted (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.17–0.68; P = 0.002) and IPTW-weighted models (odds ratio [OR]: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.21–0.68; P = 0.001). This protective effect was also observed for 28-day mortality (PS-adjusted HR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.21–0.72; P = 0.003). Clinical improvement by day +14 was higher in the CS-TCZ group with IPTW analysis only (OR: 2.26; 95% CI: 1.49–3.41; P < 0.001). The occurrence of secondary infection was similar between both groups.

Conclusions

The combination of corticosteroids and TCZ was associated with better outcomes among patients aged ≥65 years with severe COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Tocilizumab, Corticosteroids, Therapy, Immunomodulation, Outcome, Mortality

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), is a novel beta-coronavirus first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China (Huang et al., 2020). Most cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection have a mild-to-moderate course, although a significant proportion of patients will ultimately develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Wang et al., 2020), which carries a high mortality rate (Wu et al., 2020). Older age has been consistently identified as a risk factor for death and poor outcomes in COVID-19. For example, a report of 72,314 cases from China found case-fatality rates of 8% and 15% for patients aged 70–79 years and >80 years, respectively, in contrast with an overall rate as low as 2.3% for the global cohort (Wu and McGoogan, 2020). In the United Kingdom the risk of death for COVID-19 patients aged >80 years was 20-fold higher than those aged 50–59 years (Williamson et al., 2020).

The pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 and associated ARDS involves a hyperinflammatory status resembling the cytokine storm release syndrome observed in patients with influenza or immune-mediated diseases (Wiersinga et al., 2020). Therefore, a growing number of immunomodulatory therapies are being tested to counteract this deleterious inflammatory response (RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al., 2020, Cavalli et al., 2020, Canziani et al., 2020, Rossotti et al., 2020, Della-Torre et al., 2020, Titanji et al., 2020, Cao et al., 2020, Diurno et al., 2020, Deftereos et al., 2020). One of the most mature approaches at this point of the pandemic involves the off-label use of the humanized anti-interleukin (IL)-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab (TCZ) (Canziani et al., 2020, Rossotti et al., 2020, Della-Torre et al., 2020), on the basis of previous experience with patients receiving chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (Kotch et al., 2019). A recently published randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated survival benefit from corticosteroid therapy in patients with ARDS (Villar et al., 2020). In the setting of COVID-19, a meta-analysis comprising more than 1,700 participants from seven RCTs reported a reduction in 28-day mortality of 34% with the administration of systemic corticosteroids compared with usual care or placebo (WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group et al., 2020).

Regardless of this emerging evidence, studies comparing both TCZ-based and corticosteroid-based therapeutic strategies are scarce (Bhimraj et al., 2020). The additional benefit to be expected from the sequential use of TCZ in the context of previous use of corticosteroids has recently been raised (Schulert, 2020). This question is particularly relevant for older patients, who have an increased risk of death due to COVID-19 but also of developing adverse events related to immunomodulatory agents, such as superinfections. The shortage of TCZ during the first weeks of the pandemic in the current setting enabled a comparative study to be performed, which focused on the vulnerable population of individuals aged ≥65 years with the objective of analyzing the value of adding TCZ to systemic corticosteroid therapy (compared with corticosteroids alone) in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the University Hospital “12 de Octubre”, which is a 1,300-bed tertiary care center located in the urban area of Madrid, Spain. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol and granted a waiver of informed consent due to its observational design. The research was performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

The study population included patients aged ≥65 years, consecutively admitted due to severe COVID-19 pneumonia from 03 March to 01 May 2020, who received intravenous (IV) corticosteroids alone (CS group) or associated with IV TCZ (CS-TCZ group) as immunomodulatory therapy. For analysis purposes, the date of administration of the first dose of any of these agents was considered as day 0. To minimize potential survivor bias, patients who died within the first 24 h (i.e. day +1) were excluded. Participants were followed-up to discharge, death (whichever occurred first), or 30 June 2020.

The following were collected from electronic medical records using a standardized case report form: demographics and comorbidities; symptoms at presentation; vital signs, laboratory values and radiological features at day 0; use of antiviral therapy; treatment-related adverse events; and outcomes. Respiratory function was assessed by the pulse oximetry oxygen saturation/fraction of inspired oxygen (SpO2/FiO2) ratio. The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) was calculated at admission. Dynamic changes over time in clinical status were assessed according to a 6-point ordinal scale: 1 - discharged home; 2 - admitted to hospital, not requiring supplemental oxygen; 3 - admitted to hospital, requiring low-flow supplemental oxygen (FiO2 <40%); 4 - admitted to hospital, requiring high-flow supplemental oxygen (FiO2 ≥40%) or non-invasive mechanical ventilation; 5 - admitted to hospital, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or both; and 6 - death.

Antiviral and immunomodulatory therapies

According to clinical practice guidelines issued by the Spanish Ministry of Health during the study period (Ministerio de Sanidad, Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias, 2020), antiviral regimens could include co-formulated lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) (200/100 mg twice daily for up to 14 days), hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (400 mg twice for the first day, followed by 200 mg twice daily for 5–10 days), and subcutaneous (SC) interferon (IFN)-β (250 μg every 48 h). Due to its presumed antiviral and immunomodulatory properties, the use of oral or IV azithromycin (500 mg daily for 3 days) was recommended. All these drugs were used off-label and oral or written informed consent was previously obtained. In addition, some patients received IV remdesivir (200 mg during the first day, followed by 100 mg daily for 5–10 days) in the context of an ongoing clinical trial. The use of empirical antibiotic therapy was contemplated for patients admitted due to COVID-19 pneumonia. Most patients received thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).

Due to shortages in TCZ supply, a multidisciplinary committee that included clinical specialties and the Department of Pharmacy was created to facilitate and standardize therapeutic decisions, as detailed elsewhere. The committee held daily meetings (except for the weekends) throughout the pandemic period. The first meeting took place on 18 March, two days after the introduction of TCZ as a therapeutic option for COVID-19 in the local protocol. The off-label use of TCZ was considered for patients potentially eligible for intensive care unit (ICU) admission, with bilateral or rapidly progressive infiltrates on chest X-ray or computerized tomography (CT) scan, and fulfilling one or more of the following criteria: respiratory rate >30 bpm and/or pulse oximetry oxygen saturation (SpO2) <92% on room air, C-reactive protein (CRP) >10 mg/dL, IL-6 >40 pg/mL, and/or D-dimers >1,500 ng/mL. Exclusion criteria included the presence of liver function abnormalities (alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase levels more than five times the upper normal limit), uncontrolled bacterial or fungal infection, or acute diverticulitis or bowel perforation. An initial IV 400 mg dose (if body weight <75 kg) or 600 mg (if body weight ≥75 kg) was administered as a 1-h infusion. A second 400 mg dose was routinely administered 12 h later, until 26 March, whereas a third dose could be given after 24 h from the first infusion for selected patients according to the treating physician’s criteria (Le et al., 2018). After that date, a single TCZ dose was administered according to the updated recommendations of the Ministry of Health of Spain, on the basis of dosing regimens approved for rheumatologic diseases (Ministerio de Sanidad and Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios, 2020).

The local protocol took into account the use of corticosteroids already in its initial version (issued on 16 March) for patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia fulfilling the same inclusion criteria established for the initiation of TCZ, when the latter agent was unavailable or in the presence of any of the exclusion criteria detailed above. Different dosing regimens were considered (mainly IV methylprednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg daily for ≤5 days or as pulses of 125–250 mg for 3 days). Beginning in April 2020, the prescription of corticosteroids was generalized for patients presenting to the Emergency Room with COVID-19 pneumonia and SpO2 <92% on room air, regardless of the subsequent administration of TCZ.

The local protocol for the management of COVID-19 was updated 11 times between 16 March and 01 May 2020. The recommendations for the use of LPV/r, HCQ and azithromycin did not change over time. As previously stated, different corticosteroid regimens were used according to the preferences of the attending physician. The majority of the members of the interdisciplinary committee recommended against the use of high-dose corticosteroids from 23 March. Nevertheless, the protocol ultimately left the decision to the physicians in charge. The protocol did not contemplate the use of remdesivir in any situation outside the clinical trial throughout the entire study period. Since 24 March, IFN-β was no longer available for prescription. The use of IV polyclonal immunoglobulins or convalescent plasma was not contemplated in the protocol.

The local protocol in place during the study period recommended the initiation of antibiotic therapy for every patient admitted due to COVID-19 pneumonia, with IV ceftriaxone (2 g daily) as the regimen most often prescribed. Length of therapy was at the discretion of the physician in charge on the basis of the result of the sputum culture (when available) and the kinetics of serum procalcitonin level in the days following hospital admission. The administration of antifungal therapy with anti-mold activity was not universal, but rather restricted to patients with high clinical suspicion of invasive fungal infection due to typical image findings on the chest CT scan (i.e. dense nodules with or without cavitation), results from fungal culture in lower respiratory tract samples, or positive serum galactomannan and/or (1,3) β-d-glucan assays.

Design of study groups

Given the relatively low baseline prescription rate and the marked surge in demand early after the beginning of the pandemic, there was a shortage of TCZ during the first weeks of March. The interdisciplinary committee decided to distribute, on a daily basis, the available doses according to three principles: a) fulfillment of the previously detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria; b) absence of a short-term life-threatening condition; c) and, providing that both previous criteria were met, the drug was preferably administered to those patients with a longer life expectancy. As a result, TCZ was more commonly prescribed to younger patients in March, whereas corticosteroids alone were widely used for patients aged ≥65 years. As the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection declined and the supply of TCZ increased, an increasing proportion of patients aged ≥65 years received this immunomodulatory drug from April 2020. This circumstance enabled comparison of two quasi-contemporary cohorts of aged patients treated with different immunomodulatory regimens: corticosteroids alone during the first period (March 2020 [CS group]), and corticosteroids associated with TCZ during the second period (April and May 2020 [CS-TCZ group]).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality by day +14 after the first dose of immunomodulatory therapy. Secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality by day +28 and clinical improvement by day +14 (defined as discharge home and/or a decrease of ≥2 points from day 0 on the 6-point ordinal scale).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were shown as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median with interquartile range (IQR), whereas qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test were applied for continuous variables, as appropriate. Baseline factors predicting clinical improvement by day +14 were analyzed by means of logistic regression, with associations expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Collinearity among explanatory variables was assessed with the variance inflation factor. Survival probabilities were graphically depicted according to the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. A landmark analysis restricted to survivors who remained hospitalized by day +4 was performed to take into account potential survivor bias. Cox regression with backward stepwise selection was used to assess the effects of different variables on mortality rates by days +14 and +28. Associations were expressed as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs.

To overcome the limitation posed by the nonrandomized design of the study, the propensity score (PS) for receiving TCZ therapy in association to corticosteroids (versus corticosteroids alone) was calculated, given the patient’s characteristics. This PS was constructed using a non-parsimonious logistic regression, with inclusion in the CS or CS-TCZ groups considered as the dependent variable and all potential confounders entered as covariates. The ability of the resulting PS to predict the observed data was calculated by means of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (auROC), and calibration was assessed with the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. The PS was applied in two ways to correct for between-group baseline disparities: as a covariable for regression adjustment, and as inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation®, Armonk, NY).

Results

Clinical characteristics of study groups

Overall, 275 patients aged ≥65 years admitted to the current center with severe COVID-19 pneumonia during the study period received systemic corticosteroids; 81 (29.5%) were also sequentially treated with TCZ. Fourteen patients who died within the first 24 h from the initiation of immunomodulatory therapy (13 in the CS group and one in the CS-TCZ group) were excluded. Therefore, 181 and 80 patients were finally analyzed within the CS and CS-TCZ groups, respectively. Treatment with TCZ was started at a median interval of 1 day (IQR: 0–5) from the initiation of corticosteroid therapy.

The mean age of the global cohort was 77.2 ± 7.7 years, 147 patients (56.3%) were males, and 240 (92.0%) were of Caucasian ethnicity. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 4.0 (IQR: 3–5). Regarding symptoms at presentation, cough was reported by 198 patients (75.9%), fever by 187 (71.6%), and dyspnea by 180 (69.0%). Among 238 patients with available data, median NEWS at admission was 4 (IQR: 2–6). Radiological lung involvement was diffuse in 179 patients (68.6%). All-cause 14-day and 28-day mortality rates were 37.2% (97/261) and 41.4% (108/261), respectively, whereas clinical improvement by day +14 was observed in 38.3% (100/216) of patients.

The clinical characteristics of patients receiving systemic corticosteroids alone or in association with TCZ were compared. As expected, in view of the evolving prescription practices over time in the current center, the majority of those within the CS group were treated during March (97.2% [176/181]), whereas most patients in the CS-TCZ group were treated during April and May (92.5% [74/80]). Patients in the CS group were significantly older and had a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions, mainly: obesity, chronic lung and heart disease, and dementia. The NEWS at admission was also higher in this group (Table 1 ). Regarding clinical status, patients in the CS-TCZ group had poorer respiratory status (as assessed by the SpO2/FiO2 ratio), lower lymphocyte counts and higher lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, and more commonly presented with bilateral alveolar involvement on chest X-ray at day 0 (i.e. the date of administration of the first dose of immunomodulatory therapy, either corticosteroids or tocilizumab). The use of LPV/r and IFN-β was more common in the CS group, whereas patients in the CS-TCZ group were more likely to be treated with remdesivir. Regarding the corticosteroid regimen administered, intermediate-dose IV methylprednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/12 h) was the most common dose in the CS group, whereas patients in the CS-TCZ commonly received 125–250 mg methylprednisolone boluses. Accordingly, the duration of corticosteroid therapy was shorter for the CS-TCZ group (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical in both study groups.

| CS group (n = 181) | CS-TCZ group (n = 80) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, years [mean ± SD] | 78.4 ± 7.7 | 74.4 ± 7.0 | <0.0001 |

| Male gender [n (%)] | 102 (56.4) | 45 (56.2) | 0.988 |

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | 0.029 | ||

| Caucasian | 173 (95.6) | 71 (88.8) | |

| Latino | 5 (2.8) | 9 (11.2) | |

| Other | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Comorbidities [n (%)] | |||

| Obesity | 74 (40.9) | 10 (12.5) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic lung diseasea | 61 (33.7) | 14 (17.5) | 0.008 |

| Chronic heart diseaseb | 45 (24.9) | 6 (7.5) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (24.3) | 22 (27.5) | 0.585 |

| Malignancy | 27 (14.9) | 13 (16.2) | 0.783 |

| End-stage renal disease | 22 (12.2) | 4 (5.0) | 0.073 |

| Dementia | 19 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.003 |

| Lower limb peripheral arterial disease | 14 (7.7) | 5 (6.2) | 0.670 |

| Solid organ transplantation | 12 (6.7) | 6 (7.5) | 0.807 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 11 (6.1) | 4 (5.0) | 1.000 |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (1.7) | 3 (3.8) | 0.375 |

| Charlson comorbidity index [median (IQR)] | 5 (3–6) | 4 (3–5) | <0.0001 |

| Previous systemic corticosteroid therapy [n (%)] | 23 (12.7) | 5 (6.2) | 0.120 |

| Current or previous smoking [n (%)] | 69 (38.1) | 28 (35.0) | 0.630 |

| Symptoms at presentation [n (%)] | |||

| Cough | 144 (79.6) | 54 (67.5) | 0.036 |

| Fever | 140 (77.3) | 47 (58.8) | 0.002 |

| Dyspnea | 122 (67.4) | 58 (72.5) | 0.412 |

| Diarrhea | 55 (30.4) | 19 (23.8) | 0.273 |

| Myalgia | 53 (29.3) | 20 (25.0) | 0.477 |

| Expectoration | 48 (26.5) | 13 (16.2) | 0.071 |

| Impaired consciousness | 15 (8.3) | 4 (5.0) | 0.346 |

| NEWS at admission [median (IQR)]c | 3 (1–5) | 6 (3.5–7) | <0.0001 |

| Interval from symptom onset to day 0, days [mean ± SD]d | 10 (7–13) | 11 (9–16) | 0.001 |

| Interval from hospital admission to day 0, days [mean ± SD]d | 4 (1–6) | 3 (1–8) | 0.432 |

| Interval from ICU admission to day 0, days [mean ± SD]d, e | 5 (2–7.5) | 0.5 (0–2.8) | 0.165 |

CS: corticosteroids; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; NEWS: National Early Warning Score; SD: standard deviation; TCZ: tocilizumab.

Includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea.

Includes congestive heart failure and coronary heart disease.

Data available for 236 patients.

Day 0 refers to the date of administration of the first dose of immunomodulatory therapy (either corticosteroids or tocilizumab).

Data for the 15 patients in which the first dose of immunomodulatory therapy was administered following ICU admission (5 and 10 patients in the CS and CS-TCZ groups, respectively).

Table 2.

Vital signs and laboratory values at the initiation of immunomodulation, and other therapies used in both study groups.

| CS group (n = 181) | CS-TCZ group (n = 80) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs at day 0a | |||

| Axillary temperature, ºC [mean ± SD] | 37.5 ± 0.9 | 37.2 ± 0.9 | 0.010 |

| Respiratory rate, rpm [mean ± SD] | 24.3 ± 7.4 | 27.5 ± 6.5 | 0.090 |

| Heart rate, bpm [mean ± SD] | 88.4 ± 17.5 | 88.2 ± 16.5 | 0.923 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio [mean ± SD] | 231.9 ± 107.8 | 191.9 ± 84.8 | 0.003 |

| SpO2/FiO2 ratio <316 [n (%)]b | 111 (75.5) | 65 (89.0) | 0.018 |

| Laboratory values at day 0a | |||

| Leucocytes, x 109 cells/L [median (IQR)] | 6.0 (4.8–8.3) | 8.6 (6.1–13.5) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocytes, x 109 cells/L [median (IQR)] | 0.8 (0.5–1.0) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.028 |

| CRP, mg/dL [mean ± SD] | 15.9 ± 9.7 | 14.8 ± 8.4 | 0.406 |

| CRP >10 mg/dL [n (%)] | 108 (68.8) | 51 (67.1) | 0.796 |

| CRP >15 mg/dL [n (%)] | 72 (45.9) | 32 (42.1) | 0.589 |

| LDH, U/L [mean ± SD]c | 412 ± 138 | 491 ± 200 | 0.002 |

| LDH >350 U/L [n (%)]c | 115 (65.3) | 60 (75.9) | 0.091 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL [median (IQR)]d | 1,034 (464–2,028) | 1,264 (640.3–1,080) | 0.253 |

| D-dimers, ng/mL [median (IQR)]e | 872 (591–1,629.5) | 1,323.5 (627.5–5,526.8) | 0.088 |

| Chest X-ray at day 0 [n (%)]a, f | 0.017 | ||

| Bilateral interstitial infiltrates | 113 (65.7) | 36 (46.2) | |

| Bilateral alveolar infiltrates | 54 (31.4) | 40 (51.3) | |

| Unilateral alveolar infiltrate | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 3 (1.7) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Corticosteroid regimeng | |||

| Duration of therapy, days [median (IQR)] | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.032 |

| Type and dosing [n (%)] | 0.001 | ||

| Methylprednisolone boluses (125–250 mg) | 48 (26.8) | 44 (57.1) | |

| Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/12 h | 15 (8.4) | 8 (10.4) | |

| Methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/12 h | 64 (35.8) | 16 (20.8) | |

| Methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/24 h | 26 (14.5) | 7 (9.1) | |

| Prednisone ≥40 mg daily | 6 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prednisone 20–40 mg daily | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Prednisone <20 mg daily | 5 (2.8) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Hydrocortisone 50–200 mg daily | 8 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Dexamethasone 20–40 mg daily | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Other treatments administered [n (%)] | |||

| LPV/r | 102 (56.4) | 22 (27.5) | <0.0001 |

| HCQ | 162 (89.5) | 76 (96.2) | 0.074 |

| Azithromycin | 130 (71.8) | 63 (78.8) | 0.370 |

| IFN-β | 34 (18.8) | 2 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Remdesivir | 1 (0.6) | 7 (8.8) | 0.001 |

CS: corticosteroids; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; IFN-β: interferon-β; IQR: interquartile range; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; LPV: lopinavir/ritonavir; SD: standard deviation; TCZ: tocilizumab.

Day 0 refers to the date of administration of the first dose of immunomodulatory therapy (either corticosteroids or tocilizumab).

Equivalent to a partial oxygen pressure (PaO2)/FiO2 ratio <300.

LDH levels at day 0 available for 255 patients.

Ferritin levels at day 0 available for 81 patients.

D-dimer levels at day 0 available for 99 patients.

Chest X-ray at day 0 available for 250 patients.

Details on corticosteroid regimen available for 256 patients.

Twenty-nine patients (11.1%) were admitted to the ICU at some point during the index hospitalization (5.5% [10/181] in the CS group and 23.8% [19/80] in the CS-TCZ group). Immunomodulation was initiated prior to or on the same day of ICU admission in 48.3% (14/29) of these patients, within a median interval of 2 days (IQR: 1–4.3). On the other hand, therapy was initiated in the remaining 51.7% (15/29) of patients after a median interval of 1 day (IQR: 0–5) from ICU admission. In the overall cohort there were no differences between patients admitted or not admitted to the ICU in 14-day (27.6% [8/29] vs. 38.4% [89/232]; P = 0.258) or 28-day mortality rates (34.5% [10/29] vs. 42.2% [98/232], respectively; P = 0.424).

Study outcomes

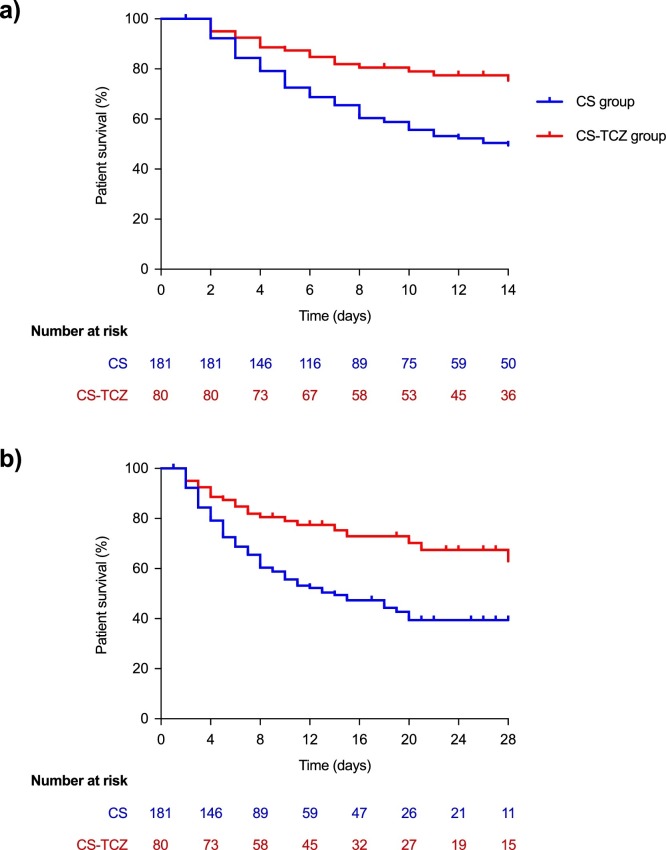

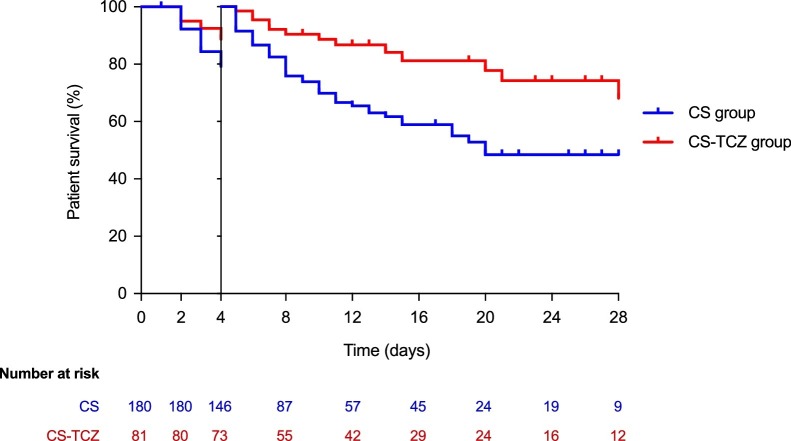

All-cause mortality by day +14 (primary outcome) was significantly lower in the CS-TCZ group than the CS group (22.5% [18/80] vs. 43.6% [79/181]; log-rank P < 0.001) (Figure 1 a). Regarding secondary outcomes, all-cause mortality by day +28 was also lower for patients within the CS-TCZ group (27.5% [22/80] vs. 47.5% [86/181]; log-rank P < 0.001) (Figure 1b). A landmark analysis on those patients surviving ≥4 days (n = 208) confirmed the benefit survival by day +28 among patients in the CS-TCZ group (Figure 2 ). There were no significant differences in the rate of clinical improvement by day +14 (45.0% [36/80] vs. 35.4% [64/181] in the CS-TCZ and CS groups; P = 0.140).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Kaplan–Meier survival curves in patients included in the CS and CS-TCZ groups: (a) by day +14 (primary study outcome); (b) by day +28 (secondary study outcome). Log-rank P < 0.001 for both comparisons.

CS: corticosteroids; TCZ: tocilizumab.

Figure 2.

Landmark survival analysis on patients surviving by day +4. Log-rank test P = 0.0024.

CS: corticosteroids; TCZ: tocilizumab.

PS-adjusted analysis

In view of the presence of baseline imbalances between both groups, the PS for receiving TCZ associated with corticosteroids (CS-TCZ group) was constructed on the basis of those clinical and analytical variables present at day 0. The following measured predictors were included: age, Caucasian ethnicity, obesity, chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, dementia, Charlson comorbidity index, cough at presentation, time since symptom onset, SpO2/FiO2 ratio <316 at day 0, lymphocyte count and LDH level at day 0, and the presence of bilateral alveolar infiltrates at day 0. The auROC of the PS was 0.849 (95% CI: 0.798–0.899), with P = 0.128 in the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, suggesting excellent discriminative capacity and model calibration, respectively.

Patients in the CS-TCZ group experienced a lower 14-day all-cause mortality in the PS-adjusted model (HR: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.17–0.68; P = 0.002), after further adjustment for the receipt of antiviral agents (HR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.25–0.74; P = 0.002), and in the IPTW-adjusted model (OR: 0.38; 95%: 0.21–0.68; P = 0.001). Regarding secondary outcomes, 28-day mortality was also significantly lower in the CS-TCZ group applying PS and IPTW adjustment, whereas clinical cure by day +7 was higher in the IPTW-adjusted model only (Table 3 ). These associations remained essentially unchanged in the landmark analysis restricted to hospitalized patients surviving at +14 days (Table S1 in Supporting material).

Table 3.

Effect of combination immunomodulatory therapy (corticosteroids plus TCZ) versus corticosteroids alone on primary and secondary study outcomes in different models.

| Model | All-cause mortality by day +14 |

All-cause mortality by day +28 |

Clinical improvement by day +14 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect estimate (95% CI) | P-value | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P-value | Effect estimate (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Crude | HR: 0.42 (0.25–0.69) | 0.001 | HR: 0.44 (0.28–0.71) | 0.001 | OR: 1.49 (0.88–2.56) | 0.141 |

| Adjusted for PS alonea | HR: 0.34 (0.17–0.68) | 0.002 | HR: 0.38 (0.21–0.72) | 0.003 | OR: 2.04 (1.01–4.13) | 0.048 |

| Adjusted for PS and other clinical covariatesb | HR: 0.43 (0.25–0.74) | 0.002 | HR: 0.47 (0.29–0.77) | 0.003 | OR: 1.41 (0.79–2.51) | 0.243 |

| Weighted by IPTW | OR: 0.38 (0.21–0.68) | 0.001 | OR: 0.42 (0.24–0.74) | 0.003 | OR: 2.26 (1.49–3.41) | <0.001 |

CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; IPTW: inverse probability of treatment weights; OR: odds ratio; PS: propensity score.

The propensity score for receiving TCZ therapy in association to corticosteroids (versus corticosteroids alone) included the following variables: age, Caucasian ethnicity, obesity, chronic lung disease, chronic heart disease, dementia, Charlson comorbidity index, cough at presentation, time since symptom onset, SpO2/FiO2 ratio <316 at day 0, lymphocyte count at day 0, LDH level at day 0, and bilateral alveolar infiltrates at day 0.

Model additionally adjusted for the receipt of LPV/r, IFN-β or remdesivir.

Treatment-related adverse events

The diagnosis of superinfection beyond day 0 was made in 6.1% (11/181) and 3.8% (3/80) of patients in the CS and CS-TCZ groups, respectively (P = 0.561). Hypertriglyceridemia (>200 mg/dL) was more common in the CS-TCZ group (18.8% [15/80] vs. 0.0% [0/181]; P < 0.0001). Elevation in liver function tests was observed in 3.9% (7/181) and 8.8% (7/80) of patients in the CS and CS-TCZ groups, respectively (P = 0.136).

Discussion

An increasing number of studies (including RCTs) support the use of systemic corticosteroids to reduce mortality in severe forms of COVID-19 (WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group et al., 2020), although the incremental effect of adding TCZ to this therapeutic approach remains unclear. The shortage of TCZ at the initial stages of the pandemic in the current setting offered the opportunity to compare two consecutive cohorts of patients aged ≥65 years and treated with different immunomodulation strategies. Patients in the CS group were older and had a greater comorbidity burden than those in the CS-TCZ group, a difference that may reflect the reluctance of treating physicians to initiate IL-6 blockade in this aged population due to concerns about potential adverse events and the greater clinical experience with the use of short courses of corticosteroids. Two patients aged >90 years underwent combination therapy, whereas 8.3% of those in the CS group were in this age stratum. Another difference was the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU during the index hospitalization (5.5% and 23.8% in the CS and CS-TCZ groups), which was likely due the evolving availability of ICU resources throughout the study period, with less beds available at the peak of the pandemic in March 2020 in coincidence with the shortage of TCZ. Nevertheless, no differences in mortality were found between patients admitted or not admitted to the ICU.

Combination therapy with corticosteroids and TCZ was found to be associated in the present cohort with lower mortality rates at 14 and 28 days as compared with the use of corticosteroids alone. The baseline imbalances in terms of age and comorbidities mentioned above would have favored the CS-TCZ group, although the clinical status at day 0 was worse in these patients (as reflected by their lower SpO2/FiO2 ratio and lymphocyte count, higher LDH level, more common bilateral alveolar involvement in the chest X-ray, and longer interval from symptom onset). The experimental use of remdesivir — a direct-acting antiviral agent inhibiting the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase that has been demonstrated to shorten the time to recovery (Beigel et al., 2020) — was more common in the CS-TCZ group (although it was administered to 8.2% of patients). In addition, more patients in the CS group received IFN-β, in keeping with the recommendations contained in the institutional protocol during the first weeks of March. Therefore, PS adjustment and IPTW were applied to take into account these differences operating in opposite senses, and still found significant risk reductions in the primary study outcome ranging 57%–66% (according to the adjusted model) in favor of the combination of corticosteroids and TCZ. On the other hand, and despite the lack of apparent impact in the crude comparison, the odds for achieving clinical response by day +14 were also significantly higher in the CS-TCZ group after balancing potential confounders by IPTW. Nevertheless, this association should be taken with caution since it was not confirmed in PS-adjusted models.

Although it was to be expected that the older age of the patients (77.2 ± 7.7 years) would have put them at an increased risk of TCZ-associated adverse events, no significant differences were found in the occurrence of bacterial or fungal infection complications between study groups. No apparent impact on the risk of secondary bacterial infection among patients treated with TCZ and corticosteroids (versus no immunomodulatory therapy) was reported from a recently published multicenter study either (Rodriguez-Baño et al., 2020). The increase of lipid levels is a well-known event in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving long-term TCZ therapy (Gabay et al., 2016), and the development of TCZ-induced hypertriglyceridemia has also been observed in the setting of COVID-19 (Morrison et al., 2020).

Some randomized clinical trials about TCZ have recently been published (Stone et al., 2020, Salvarani et al., 2021, Hermine et al., 2021); none of them has achieved definitive conclusions about the role of this drug. Moreover, none of them have specifically considered the combined treatment of TCZ and CS. Few previous studies have investigated the effectiveness of the association between TCZ and corticosteroids for severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Hazbun et al. described a small series of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation with no control group (Hazbun et al., 2020). Ramiro et al. compared a two-step approach based on high-dose methylprednisolone followed by TCZ if needed in non-responders with a historic control group receiving standard of care alone. The authors found that this sequential strategy accelerated respiratory recovery, decreased in-hospital mortality and reduced the likelihood of invasive mechanical ventilation (Ramiro et al., 2020). On the contrary, Rodríguez-Baño et al. reported no differences in the risk of intubation or death among patients treated with combination therapy (Rodriguez-Baño et al., 2020).

This study had a number of limitations. First, due to its retrospective observational design, the impact of unmeasured confounders cannot be completely ruled out, even after PS-based and IPTW adjustments. As discussed above, the direction of potential bias was not obvious in view of the nature of baseline imbalances, since patients in the CS group were older and had a higher burden of comorbidities (including chronic lung disease and dementia), whereas those in the CS-TCZ group showed increased disease severity by day 0 (as suggested by lower SpO2/FiO2 ratio and lymphocyte counts and higher LDH levels). As previously mentioned, more patients were admitted to the ICU in the CS-TCZ group than in the CS group, likely reflecting their younger age. However, no significant differences in mortality rates were found between patients admitted to the ICU and those staying in a hospital ward. Likewise, the risk of survivor bias was attempted to be minimized by excluding those patients dying within the first 24 h and by means of landmark survival analyses. Second, there was heterogeneity in the regimens of corticosteroids and TCZ, preventing a conclusion on optimal dosing strategies. It should be noted that most of the patients were treated before publication of the results from the RECOVERY Trial (RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al., 2020), and therefore low-to-intermediate-dose dexamethasone was less commonly used than methylprednisolone boluses. No individual information was collected about the level of compliance with the recommendation established in the institutional protocol for LMWH prophylaxis in patients admitted due to COVID-19 pneumonia, although no between-group differences in this variable are to be expected. Finally, the single-center design hampered the applicability of the findings to other settings.

The Infectious Disease Society of America has recently highlighted in their evidence-based guidelines (Bhimraj et al., 2020) that RCTs constitute the optimal framework to evaluate the efficacy and safety of newer therapies for COVID-19. Indeed, a number of ongoing trials are aimed at comparing TCZ versus corticosteroids (NCT04345445 and NCT04377503), corticosteroids alone or associated with TCZ (NCT04476979), and TCZ versus TCZ plus corticosteroids (NCT04486521). Until the results of these RCTs become available, observational studies might be useful to guide clinical decisions, providing that caution is applied before concluding on potential causation.

In conclusion, this experience suggests that the use of IV TCZ on top of corticosteroid therapy may be more useful than corticosteroids alone to improve outcomes in patients aged ≥65 years with hyperinflammatory status triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Ethical approval

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital “12 de Octubre” approved the study protocol and granted a waiver of informed consent due to its observational design.

Funding sources

This work was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain (COVID-19 call COV20/00181) — co-financed by European Development Regional Fund A way to achieve Europe. M.F.R. holds a research contract “Miguel Servet” (CP 18/00073) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no potential conflict of interest regarding this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the healthcare workers involved in the response to the current pandemic in the hospital and, singularly, those who suffered COVID-19.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.099.

Appendix A

Other members of the H12O Immunomodulation Therapy for COVID-19 Group:

Unit of Infectious Diseases: Manuel Lizasoain, Tamara Ruiz-Merlo, Patricia Parra; Department of Pharmacy: José Miguel Ferrari; Department of Pneumology: Javier Sayas Catalán, Eva Arias Arias; Department of Nephrology: Fernando Caravaca, Amado Andrés, Manuel Praga; Department of Rheumatology: María Martín-López; Department of Hematology: Denis Zafra, Cristina García Sánchez; Department of Oncology: Carmen Díaz-Pedroche, Flora López, Luis Paz-Ares; Department of Intensive Care Medicine: Jesús Abelardo Barea Mendoza, Paula Burgueño Laguía, Helena Domínguez Aguado, Amanda Lesmes González de Aledo, Juan Carlos Montejo; Department of Emergency Medicine: Antonio Blanco Portillo, Laura Castro Reyes, Manuel Gil-Mosquera, José Luis Montesinos Díaz, Isabel Fernández-Marín; Department of Immunology: Óscar Cabrera-Marante, Antonio Serrano-Hernández, Daniel Pleguezuelo, Édgar Rodríguez de Frías, Paloma Talayero, Laura Naranjo-Rondán, Ángel Ramírez-Fernández, María Lasa-Lázaro, Daniel Arroyo-Sánchez, Rocío Laguna-Goya; Department of Microbiology: Rafael Delgado, María Dolores Folgueira.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Beigel J.H., Tomashek K.M., Dodd L.E., Mehta A.K., Zingman B.S., Kalil A.C. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 — final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhimraj A., Morgan R.L., Shumaker A.H., Lavergne V., Baden L., Cheng V.C. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;(April) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa478. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canziani L.M., Trovati S., Brunetta E., Testa A., De Santis M., Bombardieri E. Interleukin-6 receptor blocking with intravenous tocilizumab in COVID-19 severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective case-control survival analysis of 128 patients. J Autoimmun. 2020;114 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Wei J., Zou L., Jiang T., Wang G., Chen L. Ruxolitinib in treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:137–46 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G., De Luca G., Campochiaro C., Della-Torre E., Ripa M., Canetti D. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e325–e331. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deftereos S.G., Giannopoulos G., Vrachatis D.A., Siasos G.D., Giotaki S.G., Gargalianos P. Effect of colchicine vs. standard care on cardiac and inflammatory biomarkers and clinical outcomes in patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019: the GRECCO-19 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della-Torre E., Campochiaro C., Cavalli G., De Luca G., Napolitano A., La Marca S. Interleukin-6 blockade with sarilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with systemic hyperinflammation: an open-label cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1277–1285. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diurno F., Numis F.G., Porta G., Cirillo F., Maddaluno S., Ragozzino A. Eculizumab treatment in patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from real life ASL Napoli 2 Nord experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24:4040–4047. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C., McInnes I.B., Kavanaugh A., Tuckwell K., Klearman M., Pulley J. Comparison of lipid and lipid-associated cardiovascular risk marker changes after treatment with tocilizumab or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1806–1812. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazbun M.E., Faust A.C., Ortegon A.L., Sheperd L.A., Weinstein G.L., Doebele R.L. The combination of tocilizumab and methylprednisolone along with initial lung recruitment strategy in coronavirus disease 2019 patients requiring mechanical ventilation: a series of 21 consecutive cases. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0145. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermine O., Mariette X., Tharaux P.L., Resche-Rigon M., Porcher R., Ravaud P. Effect of tocilizumab vs. usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:32–40. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch C., Barrett D., Teachey D.T. Tocilizumab for the treatment of chimeric antigen receptor T cell-induced cytokine release syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:813–822. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1629904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le R.Q., Li L., Yuan W., Shord S.S., Nie L., Habtemariam B.A. FDA approval summary: tocilizumab for treatment of chimeric antigen receptor T cell-induced severe or life-threatening cytokine release syndrome. Oncologist. 2018;23:943–947. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Centro de Coordinación de Alertas y Emergencias Sanitarias . 2020. Documento técnico de manejo clínico de pacientes con enfermedad por el nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19) [in Spanish] Available at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/documentos/Protocolo_manejo_clinico_ah_COVID-19.pdf [Accessed 29 July 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios . 2020. Tratamientos disponibles para el manejo de la infección respiratoria por SARS-CoV-2 (version March 27, 2020) [In Spanish] Available at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/laAEMPS/docs/medicamentos-disponibles-SARS-CoV-2-27-3-2020.pdf?x19374 [Accessed 29 July 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A.R., Johnson J.M., Ramesh M., Bradley P., Jennings J., Smith Z.R. Acute hypertriglyceridemia in patients with COVID-19 receiving tocilizumab. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1791–1792. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro S., Mostard R.L.M., Magro-Checa C., van Dongen C.M.P., Dormans T., Buijs J. Historically controlled comparison of glucocorticoids with or without tocilizumab versus supportive care only in patients with COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome: results of the CHIC study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1143–1151. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;(July) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Baño J., Pachon J., Carratala J., Ryan P., Jarrin I., Yllescas M. Treatment with tocilizumab or corticosteroids for COVID-19 patients with hyperinflammatory state: a multicentre cohort study (SAM-COVID-19) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(August):244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.010. S1198-743X(20)30492-4. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossotti R., Travi G., Ughi N., Corradin M., Baiguera C., Fumagalli R. Safety and efficacy of anti-IL6-receptor tocilizumab use in severe and critical patients affected by coronavirus disease 2019: a comparative analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvarani C., Dolci G., Massari M., Merlo D.F., Cavuto S., Savoldi L. Effect of tocilizumab vs. standard care on clinical worsening in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:24–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulert G.S. Can tocilizumab calm the cytokine storm of COVID-19? Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e449–51. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30210-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J.H., Frigault M.J., Serling-Boyd N.J., Fernandes A.D., Harvey L., Foulkes A.S. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titanji B.K., Farley M.M., Mehta A., Connor-Schuler R., Moanna A., Cribbs S.K. Use of baricitinib in patients with moderate and severe COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;(June) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa879. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J., Ferrando C., Martinez D., Ambros A., Munoz T., Soler J.A. Dexamethasone treatment for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group, Sterne J.A.C., Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiersinga W.J., Rhodes A., Cheng A.C., Peacock S.J., Prescott H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., Bacon S., Bates C., Morton C.E. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.