Abstract

Purpose:

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth face risks for negative sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes; it is critical to provide these populations with health education that is both inclusive of and specific to their needs. We sought to characterize the strengths and weaknesses of SGM-related messages from web sites that address SRH for young people. We considered who is included, what are topics discussed, and how messages are framed.

Methods:

A systematic Google search and screening process was used to identify health promotion web sites with SRH content for adolescents and young adults. Using MAXQDA, we thematically coded and analyzed SGM content qualitatively.

Results:

Of thirty-two SRH web sites identified, twenty-three (71.9%) contained SGM content. Collectively, the sites included 318 unique SGM codes flagging this content. Approximately two thirds of codes included messages that discussed SGM youth in aggregate (e.g., LGBT)—specific content about the diverse sub-populations within this umbrella term (e.g., transgender youth) were more limited. In addition to SRH topics, most web sites had messages that addressed a broad array of other health issues including violence, mental health, and substance use (n=17, 73.9%) and SGM-specific topics, for example coming out (n=21, 91.3%). The former were often risk-framed, yet affirmational messages were common. Most web sites (n=16; 69.6%) presented information for SGM youth both in standalone sections and integrated into broader content. Yet, integrated information was slightly more common (56.6% of all codes) than standalone content.

Conclusions:

Challenges of developing SRH content related to SGM youth include: (1) aggregate terms, which may not represent the nuances of sexual orientation and gender, (2) balancing risk versus affirmational messages, and (3) balancing stand-alone versus integrated content. However, SGM-related content also offers an opportunity to address diverse topics that can help meet the needs of these populations.

Purpose

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth are broadly defined as youth whose sexual orientation (in terms of attraction, behavior, or identity) or gender identity or expression differs from common societal or cultural norms. Compared to their non-SGM peers, SGM youth are at increased risk of poor sexual and reproductive health (SRH) outcomes, including HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unintended pregnancy.1–3 Additionally, SGM youth are at disproportionate risk for negative health behaviors and experiences that often co-occur with sexual risk, such as violence victimization, substance use, and suicidality.2,4 Given these health disparities, there is a need for health education that is both inclusive of and specific to SGM youth.5 However, SGM youth are less likely to report receiving sexual health education, perhaps because the content does not resonate with them.6,7 In fact, surveillance data suggests that inclusion of sexual orientation-related topics, gender roles, gender identity, or gender expression in high school sexual health education classes across the United States (U.S.) is sub-optimal.8

To improve health education for SGM youth going forward, it is important to characterize the strengths and weaknesses of existing content. The wealth of online health promotion information from public health and medical organizations provides a valuable opportunity for such assessment. Moreover, strengthening online content has the potential to complement school- and clinic-based education given its current reach among young people, including SGM youth. Data suggest that the majority of adolescents have used the internet for health-related purposes,9 and compared to heterosexual youth, a higher proportion of sexual minority youth access sexual health information online.10 However, to date, limited research has assessed online SRH information related to SGM youth; a few studies have examined whether health promotion content for adolescents is inclusive of SGM youth, but in-depth exploration of the specific messages relevant to this population is lacking.11,12

Consideration of the audience, topics, and framing of this content is an important first step. Audience segmentation, which refers to direct targeting and tailoring of messages to increase effectiveness and efficiency,13 is commonly done with SRH content.14 Applying this strategy for SGM youth may be particularly complex given the diversity of sexual orientations, based on attraction, behavior, and identity and of gender identities and expressions. As for the specific topics addressed in sexual health education, evidence of syndemics or multiple, intersecting health issues (e.g., substance use and mental health) contributing to the transmission of STIs and HIV, particularly among SGM populations, would suggest a need to include a variety of health topics beyond SRH.15–18 In terms of framing, research suggests that how messages are presented, including the specific dimensions that are emphasized or de-emphasized, affect the extent to which such information contributes to behavior change.19–21 Framing is thus particularly important to consider within the context of health education efforts for young people.

Accordingly, we conducted a content analysis of SGM-related messages in health promotion web sites with SRH information for youth, examining audience segmentation, health topics, and framing. Three research questions guided this analysis: (1) Who is included?; (2) What topics are addressed?; and (3) How is the information framed? Using this framework of who, what, and how, we characterize the health messages for SGM youth to inform health education efforts for these populations.

Methods

Data collection

Data for this analysis come from web sites with content about sexual and reproductive health for adolescents and young adults included as part of a larger study to assess integration of STI prevention messages with information about pregnancy prevention, particularly highly and moderately effective contraception (e.g., intrauterine devices [IUDs], implants, birth control pills).22 Web site identification involved keyword searches in Google using combinations of plain language terms related to adolescents (i.e., teen, young, youth, girls) and SRH (i.e., sexual health, sex education, birth control, IUD, implant, the pill), with an emphasis on pregnancy prevention given the objective of the primary study. As part of a systematic screening process, two screeners independently assessed unique URLs (n=610) from the first five pages of each search term combination to determine web site eligibility. To be included, web sites had to be associated with a U.S.-based organization with a mission related to health promotion or the provision of health services and to include original content about sexual and reproductive health explicitly for adolescents and/or young adults. Fifty-one URLs from 30 unique web sites were eligible, and consultation with adolescent sexual and reproductive health experts led to the addition of two web sites, for a total sample of 32 web sites. English-language informational text content about sexual and reproductive health from each web site was selected using a defined protocol and converted to a PDF. We excluded videos, clinic locator information, birth control reminders, blogs, and quizzes. Additional information about the methods for identifying web sites is published elsewhere.22

Analysis

This analysis used a multi-stage approach to identify and analyze content specifically related to sexual minority youth, defined broadly in terms of attraction, behavior, and identity, and gender minority youth, based on identity and/or expression. Hereafter, we refer to this content as “SGM content” for simplicity.

SGM content identification.

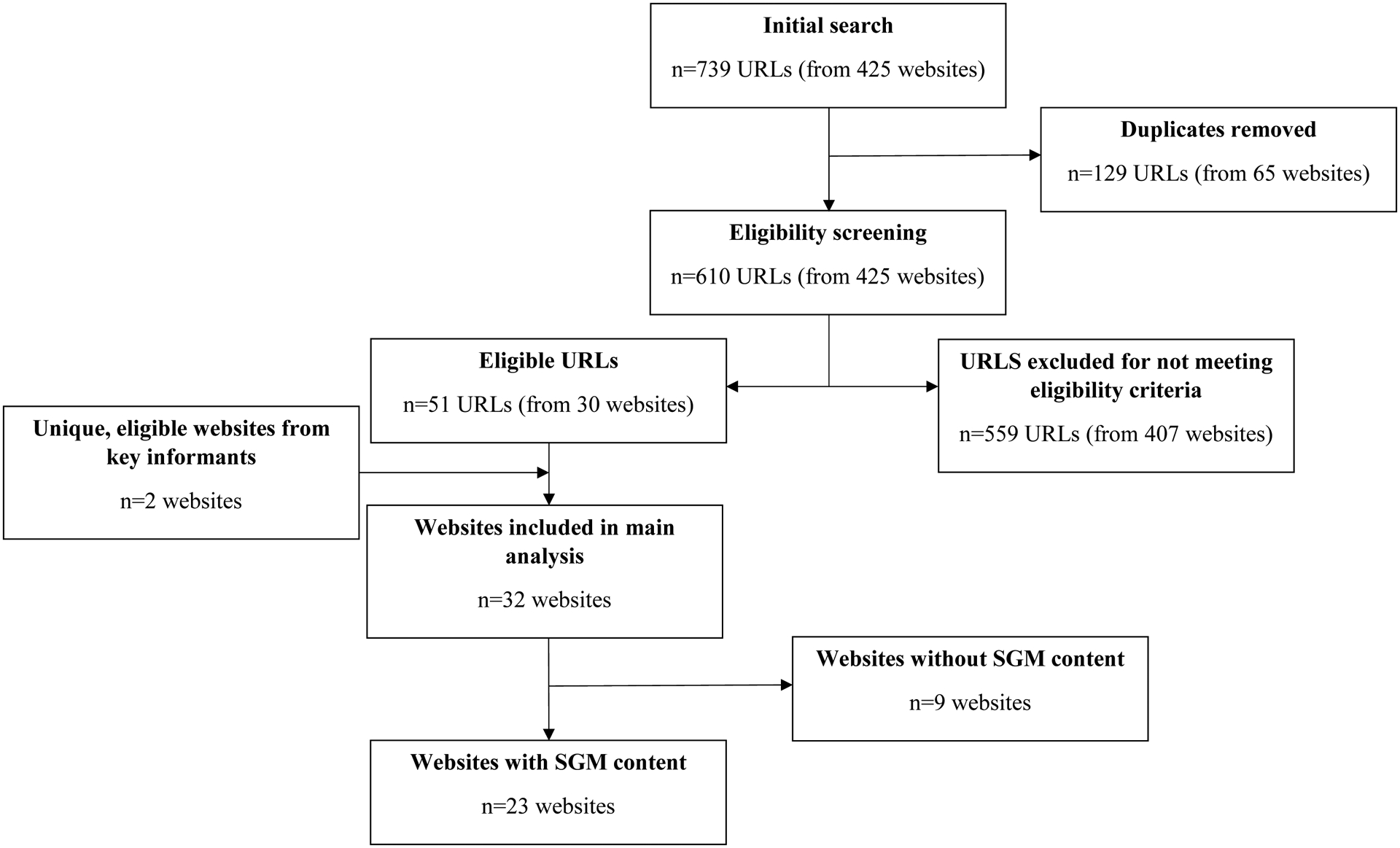

An initial round of coding for the main study allowed us to capture and abstract SGM content. Specifically, web site PDFs were uploaded into MAXQDA version 12.3 (VERBI Software) and two coders (RJS and CNR) independently coded six web sites using a defined codebook that included an “SGM” code. After reconciling differences from this initial subset, the coders then independently coded another eight web sites to ensure reliability of code applications. Because 89% agreement was achieved, one individual coded the remaining web sites. Of the 32 web sites included in the main study, 23 (71.9%) web sites contained SGM content which are included in the current analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates the systematic search process and SGM content identification.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for identification of SGM content, adapted from Steiner et al., 201822

SGM content thematic coding.

For this specific study, we followed the principles of thematic qualitative analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke.23 Three authors (JA, RJS, and CNR) conducted a second round of coding to apply more nuanced codes to the sections of text that had received the broad SGM code in the initial round of coding. These three authors independently reviewed six web sites that collectively included 25% of the SGM codes to identify inductive codes based on the data. We then developed a codebook that included both deductive (e.g., behavior, identity, and attraction) and inductive (e.g., coming out, stigma, risk, and affirmations) codes. All authors coded seven web sites and reconciled differences through discussion until consensus about consistent application of codes was reached. The remaining content was then double coded independently. The two coders met regularly to discuss and resolve discrepancies. We identified themes by iteratively reviewing the coded content. To contextualize certain qualitative findings, we also present select descriptive statistics.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 23 web sites with SGM content, most were either run by nonprofit education/advocacy organizations (n=9, 39%) or local health systems/clinics (n=8, 35%) (Table 1). All 23 contained informational webpages; seven also contained “question and answer” sections. More information about the characteristics of these web sites can be found elsewhere.22 Collectively, the sites included 318 unique SGM codes. Web sites ranged from containing one to 102 SGM codes (median=6).

Table 1.

Websites, organization, and organization type.

| Website | Organization | Organization Type | Organization Locationa |

|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.acog.org/ | The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | National Professional Medical Organization | Washington D.C. |

| https://annexteenclinic.org/ | Annex Clinic | Local medical provider | Robbinsdale, MN |

| https://www.bedsider.org/ | Power to Decide (Formerly the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) | National Nonprofit Organization | Washington D.C. |

| https://teenclinic.org/ | Boulder Family Women’s Health Center | Local Medical Provider | Boulder, CO |

| https://fairview.org/ | Fairview Health Services | Local Medical Provider | Minneapolis, MN |

| http://girlshealth.gov/ | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Women’s Health | Federal Government | Washington D.C. |

| https://goaskalice.columbia.edu/ | Columbia University | Academic Institution | New York, New York |

| https://healthychildren.org/ | American Academy of Pediatrics | National Professional Medical Organization | Itasca, IL |

| http://www.helpnothassle.org/ | The Youth Project | Local Nonprofit Organization | Santa Clarita, CA |

| http://www.iwannaknow.org/teens.html | American Sexual Health Association | National non-profit organization that promotes sexual health through advocacy and education | Research Triangle Park, NC |

| https://kidshealth.org/ | Nemours Children’s Health System | Nonprofit pediatric health system | United Statesb |

| http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ | LA County Department of Public Health | Local Health Department | Los Angeles, CA |

| http://www.pamf.org/ | Palo Alto Medical Foundation | Local Nonprofit Health Care | CAc |

| https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/teens | Planned Parenthood Federation of America | National sexual and reproductive health care advocate and provider | United Statesb |

| http://positive.org/ | Coalition for Positive Sexuality | Non-profit advocacy and sex education organization | Chicago, IL |

| https://safeteens.org/sex-pregnancy-stds/ | Maternal and Family Health Services, Inc. | Non-profit health and human services organization | Wilkes-Barre, PA |

| http://www.scarleteen.com/ | Scarleteen | Independent, grassroots sexuality and relationships education and support organization and website | Chicago, IL |

| https://sexetc.org/ | Answer | National Sexuality Education Organization | Piscataway, NJ |

| https://stayteen.org/ | Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and unplanned Pregnancy) | National nonprofit organization | Washington D.C. |

| https://www.summitmedicalgroup.com/ | Summit Medical Group | Physician-owned multispecialty practice | NJc |

| https://www.teensource.org/ | Essential Access Health | Administrator of California’s Title X federal family planning program | CAc |

| https://youngmenshealthsite.org/ | Boston Children’s Hospital | Local medical center | Boston, MA |

| https://youngwomenshealth.org/ | Boston Children’s Hospital | Local medical center | Boston, MA |

These locations are based on contact information provided by the organization online.

Multiple locations provided within country.

Multiple locations provided within state.

Who is included in SGM content?

Use of aggregate terms.

Most web sites referenced SGM youth as a homogenous group using aggregate terms related to populations (e.g., lesbian, gay bisexual and transgender [LGBT]) or constructs (e.g., sexual orientation and gender identity). Approximately two-thirds of the relevant content used such aggregate terms, even when more nuanced descriptions would be useful. For example, this use of “LGBTQ youth” could be interpreted as suggesting that the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth are all the same: “Coming out to your doctor is an important step. There are important health issues that are unique to LGBTQ youth that you should discuss with your health care provider.”

Most web sites also used “sexual orientation and gender identity,” either independently or with terms such as “LGBTQ.” Although this language could also imply a homogenous group, some sites appropriately distinguished “sexual orientation” and “gender identity”. For example,

“You may see the letters “LGBT” or (“LGBTQ”) used to describe sexual orientation. This abbreviation stands for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender” (or “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning”). Transgender isn’t really a sexual orientation — it’s a gender identity. Gender is another word for male or female. Transgender people may have the body of one gender, but feel that they are the opposite gender, like they were born into the wrong type of body.”

Conversely, some messages conflated the constructs of sexual orientation and gender identity, typically by using straight or heterosexual as the converse of LGBTQ. For example, “There are also substantially greater numbers of unintended pregnancies among those aged 20–24 than among younger people, and rates of teen pregnancy are higher for LGBTQ youth than heterosexual (straight) youth.”

Even when gender identity was clearly differentiated from sexual orientation, transgender youth were frequently discussed as a singular group, with little acknowledgement of the many gender identities that fall under the umbrella term “transgender” (e.g., transgender men, transgender women, genderqueer, agender). Moreover, only ten web sites had specific content for transgender youth independent of content for sexual minority youth. Specifically, one web site had content tailored for transgender women, four web sites for transgender men, and two web sites for non-binary gender identities. The remaining three web sites address multiple identities that fall under the umbrella term transgender. As a specific example, the following content addressed reproductive health for transgender men.

“Mal hasn’t always had the best experiences going to the doctor’s office, so it took him some time to work up the courage to ask a health care provider about getting an IUD. At first he wanted an IUD to help with heavy periods. He didn’t feel like he should have periods at all, so the Mirena really helped his self-confidence. When Mal started taking hormones to transition, he worried that the IUD would have to go. Fortunately, his doctor clarified that the hormone in the Mirena would actually help with his vaginal health during the transition.”

Various dimensions of sexual orientation and gender are emphasized.

In some cases, sexual orientation was comprehensively characterized by the three dimensions of behavior, identity, and attraction. For example, one web site stated, “Sexual attraction, which is part of “sexual orientation,” refers to the gender of a person who we become sexually attracted to. Sexual orientation also includes how we identify our feelings (e.g., “lesbian” or “bisexual”) and who we have sex with.” However, web sites also equated sexual orientation with only attraction, with some even explicitly stating that identity and behavior do not determine sexual orientation. Some sites also emphasized that sexual identity is fluid and can change over time, while simultaneously describing sexual orientation as a fixed trait. Overall, attraction was the dimension most frequently discussed by web sites, followed by behavior, and identity. Gender was typically discussed in terms of gender identity more so than gender expression. Only six web sites described gender variance in terms of gender expression.

What topics are addressed in SGM content?

Pregnancy, STI, and HIV prevention addressed.

Notably, most web sites addressed pregnancy and/or birth control in relation to these populations, often highlighting the importance of pregnancy prevention for SGM youth who, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, may have sexual experiences that put them at risk for unintended pregnancy (see Table 2 for a specific example). However, while emphasizing the importance of SRH for SGM youth, few web sites discussed specific SRH topics particularly salient for SGM youth, such as the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and nonoccupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) as HIV prevention strategies and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and puberty blockers for transgender youth (Table 2). In fact, although most web sites addressed STIs in SGM content, only half specifically mentioned HIV/AIDS in relation to this population. Condoms and testing were commonly cited prevention methods (Table 2). Dental dams or other barrier methods were also discussed, particularly for cisgender lesbian youth (e.g., “Lesbians should use dental dams to help avoid STIs”).

Table 2.

Topics and select example messages.

| Topics | Examples |

|---|---|

| SGM-specific Topics | |

| Allies | What are homophobia and transphobia? Homophobia is a term that describes negative feelings and attitudes toward LGB people. Transphobia is a similar term that describes negative feelings and attitudes towards transgender and gender nonconforming people. What are some examples of homophobia and transphobia? Negative feelings and attitudes about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) people can be shown in different ways. Some ways are obvious and intentional; for example, direct insults, threats, bullying, physical harm or violence, and discrimination. Some ways are less obvious. Examples of these hidden forms of homophobia or transphobia include people who aren’t comfortable around LGBT people; the use of slurs/words in an unintentional way; and avoiding discussions about LGBT issues due to feeling uncomfortable. All types of homophobic and transphobic attitudes and behaviors can be hurtful and sometimes dangerous to LGBT people. (Stigma) |

| Coming out | |

| Definitions of SGM-related terms | |

| Having an LGBT-identified parent | |

| Identity exploration | |

| Stigma | |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health | |

| Abstinence | It’s very common for boys and girls who later identify as gay to have sex with opposite-sex partners. All teens who are sexually active with opposite-sex partners need to use birth control to prevent an unwanted pregnancy. It also is important to use a condom every time to protect against sexually transmitted infections (STIs). (Birth control, Condoms, STIs) Some transgender people decide to use hormones, or younger trans people might use puberty blockers to prevent them from going through puberty for the sex they were assigned at birth, to have their bodies more closely match their gender identities. (Puberty blockers, HRT) PrEP is the use of an antiretroviral drug (Truvada) to prevent HIV infection in HIV negative individuals who are at significant risk of becoming HIV positive. Recent research has demonstrated that the use of this medication has significantly reduced the risk of HIV infection in men who have sex with men, injection drug users, heterosexual cisgender women, and transgender women. (PrEP, HIV/AIDS) |

| Birth control | |

| Condoms | |

| Dental dams | |

| HIV/AIDS | |

| HIV/STI testing | |

| HRT | |

| Pregnancy | |

| PrEP & nPEP | |

| Puberty blockers | |

| STIs | |

| Co-Occurring Health Risks | |

| Bullying or violence | Adolescence can be an exciting but also a challenging time for everybody, since it is a period when bodies change, schoolwork is more difficult, and friends and families might not understand your feelings and thoughts. Sometimes adolescents feel more anxious, depressed, or even suicidal. Other times, adolescents can turn to risky behaviors such as drugs, alcohol or sex. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth, and youth who identify as transgender or gender nonconforming experience the same mental health issues as other adolescents. However, they may also feel alone and might not share their feelings about sexual orientation or gender identity because they fear people will reject them. (Mental health, Substance use) |

| Mental health | |

| Sexual abuse or partner violence | |

| Substance use | |

| Relationships | |

| Friends/peers | For people of all sexual orientations, learning about sex and relationships can be difficult. It can help to talk to someone about the confusing feelings that go with growing up — whether that someone is a parent or other family member, a close friend or sibling, or a school counselor. […] In many communities, youth groups can provide opportunities for LGBT teens to talk to others who are facing similar issues. Psychologists, psychiatrists, family doctors, and trained counselors can help them cope — confidentially and privately — with the difficult feelings that go with their developing sexuality. (Friends, Parents/family, Patient-provider interactions, Trusted adults) |

| Parents/family | |

| Patient-provider interactions | |

| Romantic relationship dynamics | |

| Trusted adults |

Abbreviations: SGM = Sexual and gender minority. HRT = Hormone replacement therapy. PrEP = Pre-exposure prophylaxis. nPEP = Nonoccupational post-exposure prophylaxis.

Diverse topics in addition to sexual and reproductive health addressed.

In addition to SRH content, most web sites included SGM content that addressed a wide range of health and other topics. A complete list of topics identified and select examples of messages in these domains are provided in Table 2. These included SGM-specific topics (e.g., coming out and allies, n=21, 91.3%); relationships, primarily with parents, family, friends, or peers (n=17, 73.9%); and health risks that often co-occur with sexual risk (i.e., violence victimization, mental health, and substance us, n=17, 73.9%). At times, these topics were addressed alongside SRH topics, for example by combining discussion of romantic relationships and STIs. Yet web sites also addressed this content separately from SRH content, for example by discussing the connection between stigma and depression and referring youth to mental health services (Table 2).

Expansive content in relation to coming out as LGBTQ.

Most web sites had extensive content related to coming out as LGBTQ, which was notable because content about other topics was typically addressed briefly. Coming out was discussed in relation to parents, family, peers, friends, trusted adults such as teachers or school counselors, and, albeit less frequently, doctors or other health care providers, often using anecdotes of youth’s actual personal experiences. Content about coming out to parents and friends described potential experiences ranging from positive to negative, often emphasizing the uncertainty of parental and peer reactions. For example, a Q&A section provided this response to a question about how to tell one’s parents about being bisexual:

“Some parents are eager and happy to talk with their kids about these issues. Some are not surprised and are welcoming when their children come out to them. Some are definitely not. That’s why coming out to parents can be intimidating and scary for so many people — no matter how old they are. Know that every family is different, and there’s probably no sure way of knowing how your parents will react, even if they are gay, lesbian, or bisexual themselves.”

How are messages related to SGM content framed?

Affirmations prevalent but risk messages also included.

A number of messages were characterized by an affirmational tone, using language such as “it’s ok” or “normal” in reference to identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, particularly in relation to exploring same-sex attraction. This framing was often used to respond to young people questioning their sexual orientation or gender identity and reinforced that it is ok not to know. For example, one young woman asked about whether engaging in sexual relations with another woman made her bisexual. The response included the following, “It’s completely normal to question your sexual orientation at any age, but especially for teenagers. You may not identify with the labels “lesbian” or “bisexual,” and that’s okay — you don’t need to label your sexuality if it doesn’t feel right to you.” That said, messages emphasizing the risks faced by SGM youth were also fairly common, although less so than affirmations. Risk messages typically addressed specific health risks related to sexual behaviors associated with unplanned pregnancy or the transmission of HIV and other STIs, as well as other health issues, such as depression, suicide, violence victimization, homelessness, and substance use. For example, “Some LGBT teens without support systems can be at higher risk for dropping out of school, living on the streets, using alcohol and drugs, and trying to harm themselves.” Across affirmational and risk messages, the content appeared intended to support the health and well-being of SGM youth; we did not identify any homophobic, biphobic, or transphobic messages.

Both standalone and integrated messages common.

SGM content was either standalone in that the information was presented on a specific page or sub-section labeled as about SGM youth (e.g., “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Teens”, “Bisexual or questioning?”) or integrated within other pages/sections (e.g., “Who can get an STD?”). Most web sites (n=16) had both standalone and integrated messages on separate pages, and a smaller number of web sites used only standalone (n=3) or integrated (n=3) messages. One web site was not coded as standalone or integrated because it only contained Q&A pages, with some questions specific to SGM youth. Overall, integrated messages were slightly more common (56.6% of all SGM codes) than standalone messages. It seemed that the audience and content varied based on the framing, with integrated content intended for a general audience, inclusive of SGM youth, and particularly focused on the SRH content, as this example illustrates: “There are many different types of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), which can be broken down into three basic types: bacterial, viral, and parasitic. All three types of infections can occur whether you are having heterosexual (opposite gender) or homosexual (same gender) sex.” In contrast, standalone messages were more targeted to SGM youth specifically and typically addressed SGM-specific topics including stigma and relationships such as interactions with trusted adults. For example:

“What are some concerns that LGBT teens may face at home, at school, and in the community? Society as a whole is changing. All states now allow same-sex couples to marry. Many schools support LGBT teens and create a safe environment for all students. Still, bullying in school can be a problem. If you are being bullied, talk to your parents, a teacher, or your principal. […] All of these factors can make an LGBT teen feel anxious and alone. LGBT teens who do not feel supported by adults in their homes and schools are more likely to be depressed.”

Discussion

This analysis provides unique insights into SRH-related health education for SGM youth, with implications for online content and health promotion efforts more broadly, including in school, community, and clinic contexts. Most SRH web sites identified in the primary study contained SGM content, albeit to varying degrees. It is promising that this content was supportive of SGM youth health and included affirmational messages that normalized the experience of SGM youth. However, of the 32 web sites identified, 9 (27.3%) did not contain any SGM content, a notable deficit given the extent to which SGM youth use the Internet for seeking SRH information.10,24 Across our research questions related to who, what, and how, we identified some challenges to presenting content that is appropriately segmented, comprehensive, and framed. That said, we also noted some strengths of existing content, which can be built upon going forward.

Several challenges we identified were related to how SGM youth and sexual orientation and gender identity were characterized, particularly given the common use of aggregate terms. Although using terms such as “LGBT” is convenient and may be appropriate for topics (e.g., violence) that apply across specific populations of SGM youth, in other cases this approach may introduce inaccuracies or confusion. It is particularly important not to conflate sexual minority and gender identity constructs and ensure that messages are tailored as needed, as in the case of certain SRH topics for which there were some positive examples (e.g., transgender men and pregnancy, lesbians and STI prevention strategies). Use of aggregate terms may contribute to overall gaps in content for distinct populations of SGM youth, such as for gender minority youth who may have diverse gender expressions but do not necessarily identify as transgender. This challenge of appropriately and comprehensively addressing all SGM populations is not unique to health education—for example, SGM health researchers face similar issues in defining and measuring sexual orientation, such as whether to use attraction, behavior, and/or identity.25

Given the general lack of attention to content specific to certain populations of SGM youth, it is not surprising that some SRH topics were not extensively addressed. For example, few web sites contained information regarding HRT and puberty blockers, topics particularly salient to transgender youth.24 Further, only about half of the web sites analyzed included SGM-related information specific to HIV/AIDS, with only one addressing PrEP and nPEP as prevention strategies, a noticeable deficit given the burden of HIV among young men who have sex with men and the fact that this population of SGM youth uses the Internet for health education on this topic.26 Of note, information about SRH, as well as health behaviors and experiences that co-occur with sexual risk (e.g., violence, substance use, and mental health) emphasized the inherent risks that SGM youth face, including social stigma that can contribute to these adverse outcomes. It is unclear whether such messages appropriately emphasize the influence of the social context,27 minimizing stigma at the individual-level, or further contribute to misperceptions that SGM youth are inherently risky.28

The fact that the SRH-focused web sites discussed topics beyond SRH that are particularly relevant to SGM youth is an important strength and somewhat surprising given the silos that exist within health promotion broadly.29 SGM youth face many health disparities and these health behaviors and experiences are often syndemic with HIV and STIs,15–18 so it is appropriate to comprehensively address a range of health issues. Moreover, SGM youth use the Internet for information seeking on a variety of topics, including sexual and gender identity exploration,24,26,30 so it makes sense to concentrate information within a single source and even extend beyond health content, as many of the sites did in discussing coming out extensively. It was promising that much of the SGM content related to exploring sexuality or gender used affirming messages that normalized this process, yet in some cases, the information on coming out was framed in a way that emphasized the potential for negative outcomes, including family rejection. Although it may be reasonable to prepare youth for adverse reactions, such messages could inadvertently deter coming out in instances where it could be helpful and supportive.

A final strength to note was the combination of standalone and integrated content used by many web sites, which may be an ideal approach. The use of standalone messages focused on SGM-specific topics likely facilitated the breadth of content addressed, including topics in addition to SRH. Yet use of integrated messages also has benefits including creating inclusive content that resonates with SGM youth, including those who are still exploring their sexual orientation or gender identity, protecting confidentiality of SGM youth who are not yet out, and educating heterosexual and cisgender youth, which has the potential to reduce SGM-related stigma.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the analysis is based on a systematic identification of web content, the original study was not intended to capture all online content addressing SRH for young people. In particular, the purpose was to understand health promotion messages from public health and clinical sources, excluding other types of online health education. However, we know that SGM youth access web-based information from a variety of sources such as medical sites, LGBT youth-center sites, community based organization, and online journal articles,24 and it is unclear to what extent SGM youth use web sites included in this analysis. Additionally, the search strategy for the original study did not include STI-related terms (to minimize selection bias in relation to the primary research question about integration of STI content with reproductive health), which may account for some of the paucity of content related to HIV. Although the search strategy used processes (e.g., disabling location services and using an “incognito browser” mode) to reduce the personalization of results by Google, it is unclear to what extent the search strategy affected which web pages were identified. Within the included web sites, it is possible that we did not capture all SGM content despite a systematic coding process. Finally, it is important to note the data were collected in the spring of 2017 and may not reflect any recent updates in the content on these sites (e.g., additional information about PrEP given approval for adolescents in 2018).

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our findings can inform the development, refinement, and evaluation of SRH-related health education messages that are both inclusive of, and specific to SGM youth, including online content and extending to other channels including sexual health education in schools, community-wide communication campaigns, and even clinic-based counseling. Such initiatives should not overly simplify the diverse populations and constructs that fall under the umbrella term sexual and gender minority youth. Although using aggregate terms may be appropriate at times, health educators should carefully consider if and how to tailor content comprehensively to address the nuances in terms of populations and constructs reflected in aggregate terminology. One potential option for ensuring clarity in online content is to define terms, noting the potential for definitions to change, and then hyperlink back to these definitions when using them on different pages within the web site. In terms of topics, content should address a range of health issues that are related to SRH and particularly salient for SGM youth, yet the optimal amount of content included should be assessed, as other research indicates too much information may be a barrier to information uptake.31 Using standalone web pages for more SGM-specific topics may be one way to effectively achieve breadth, yet this should be evaluated, along with integrated messages. Likewise, evaluating the framing of messages in relation to risks versus affirmations can help health educators understand how acceptable and impactful these approaches are for SGM youth. Across these potential implications, health communications research that includes SGM youth is an obvious next step, including studies of what content is most important to and resonates with SGM youth. Such efforts can build on our analysis of SGM-related online health education messages to strengthen health promotion for this population.

So What?

What is already known about this topic?

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth represent diverse populations who experience numerous health disparities, requiring tailored and comprehensive health education. However, sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information for these populations remains sub-optimal.

What does this article add?

This article characterizes SGM-related content included in online SRH health promotion information for adolescents and young adults to inform how to strengthen health promotion efforts for these populations going forward.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Health educators should be careful not to conflate populations that fall within the umbrella term SGM youth, especially when using aggregate terms such as LGBT. While education on diverse topics is likely needed for SGM youth, health educators should assess the optimal amount of content for online health messages. Health educators also should consider the appropriate framing of health messages for SGM youth, such as risks versus affirmations and standalone (SGM youth only messages) versus integrated (messages for all youth) strategies.

Funding:

This work was supported by Emory University Professional Development Support Funds and Letz Funds from Emory University’s Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Rasberry CN, Lowry R, Johns M, et al. Sexual Risk Behavior Differences Among Sexual Minority High School Students—United States, 2015 and 2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(36):1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender Identity and Experiences of Violence Victimization, Substance Use, Suicide Risk, and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among High School 0Students—19 States and Large Urban School Districts, 2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;68(3):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. J Sex Res. March 2011;48(2–3):218–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns MM, Lowry R, Rasberry CN, et al. Violence Victimization, Substance Use, and Suicide Risk Among Sexual Minority High School Students—United States, 2015–2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(43):1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trust for America’s Health. Furthering the adaptation and implementation of LGBTQ-inclusive sexuality educaiton. https://www.tfah.org/report-details/furthering-the-adaptation-and-implementation-of-lgbtq-inclusive-sexuality-education/. Published May 2016. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- 6.Rasberry CN, Condron DS, Lesesne CA, Adkins SH, Sheremenko G, Kroupa E. Associations Between Sexual Risk-Related Behaviors and School-Based Education on HIV and Condom Use for Adolescent Sexual Minority Males and Their Non-Sexual-Minority Peers. LGBT Health. January 2018;5(1):69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbeit MR, Fisher CB, Macapagal K, Mustanski B. Bisexual Invisibility and the Sexual Health Needs of Adolescent Girls. LGBT Health. October 2016;3(5):342–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brener ND, Demissie Z, McManus T, Shanklin SL, Queen B, Kann L. School health profiles 2016: Characteristics of health programs among secondary schools. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park E, Kwon M. Health-Related Internet Use by Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review. Journal of medical Internet research. 2018;20(4):e120–e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Korchmaros JD, Kosciw JG. Accessing sexual health information online: use, motivations and consequences for youth with different sexual orientations. Health Education Research. 2013;29(1):147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiteley LB, Mello J, Hunt O, Brown LK. A review of sexual health web sites for adolescents. Clinical pediatrics. 2012;51(3):209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marques SS, Lin JS, Starling MS, Daquiz AG, Goldfarb ES, Garcia KC, Constantine NA. Sexuality education websites for adolescents: a framework-based content analysis. Journal of health communication. 2015;20(11):1310–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slater MD. Theory and method in health audience segmentation. Journal of health communication. 1996;1(3):267–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman AL, Kachur RE, Noar SM, McFarlane M. Health communication and social marketing campaigns for sexually transmitted disease prevention and control: What is the evidence of their effectiveness? Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(2S):S83–S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coulter RW, Kinsky SM, Herrick AL, Stall RD, Bauermeister JA. Evidence of syndemics and sexuality-related discrimination among young sexual-minority women. LGBT health. 2015;2(3):250–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poteat T, Scheim A, Xavier J, Reisner S, Baral S. Global epidemiology of HIV infection and related syndemics affecting transgender people. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2016;72(Suppl 3):S210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Garofalo R, et al. An index of multiple psychosocial, syndemic conditions is associated with antiretroviral medication adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(4):185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. August 2007;34(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. The Relative Persuasiveness of Gain-Framed Loss-Framed Messages for Encouraging Disease Prevention Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Health Communication. 2007/10/11 2007;12(7):623–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. The Relative Persuasiveness of Gain-Framed and Loss-Framed Messages for Encouraging Disease Detection Behaviors: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Communication. 2009;59(2):296–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher KM, Updegraff JA. Health Message Framing Effects on Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-analytic Review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;43(1):101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner RJ, Rasberry CN, Sales JM, et al. Do health promotion messages integrate unintended pregnancy and STI prevention? A content analysis of online information for adolescents and young adults. Contraception. 2018;98(2):163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology. 2008;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeHaan S, Kuper LE, Magee JC, Bigelow L, Mustanski BS. The interplay between online and offline explorations of identity, relationships, and sex: a mixed-methods study with LGBT youth. J Sex Res. 2013;50(5):421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrager SM, Steiner RJ, Bouris AM, Macapagal K, Brown CH. Methodological Considerations for Advancing Research on the Health and Wellbeing of Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. LGBT Health. May-Jun 2019;6(4):156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: a mixed-methods study. Arch Sex Behav. April 2011;40(2):289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederdeppe J, Bu QL, Borah P, Kindig DA, Robert SA. Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. The Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(3):481–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dwyer A. “We’re Not Like These Weird Feather Boa-Covered AIDS-Spreading Monsters”: How LGBT Young People and Service Providers Think Riskiness Informs LGBT Youth–Police Interactions. Critical Criminology. March 01 2014;22(1):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparks M. The changing contexts of health promotion. Health Promotion International. 2013;28(2):153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magee JC, Bigelow L, Dehaan S, Mustanski BS. Sexual health information seeking online: a mixed-methods study among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young people. Health Educ Behav. June 2012;39(3):276–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patterson SP, Hilton S, Flowers P, McDaid LM. What are the barriers and challenges faced by adolescents when searching for sexual health information on the internet? Implications for policy and practice from a qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect. 2019:sextrans-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]