Abstract

Outbreaks of yaws-like ulcerative skin lesions in children are frequently reported in tropical and sub-tropical countries. The origin of these lesions might be primarily traumatic or infectious; in the latter case, Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue, the yaws agent, and Haemophilus ducreyi, the agent of chancroid, are two of the pathogens commonly associated with the aetiology of skin ulcers. In this work, we investigated the presence of T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi DNA in skin ulcers in children living in yaws-endemic regions in Cameroon.

Skin lesion swabs were collected from children presenting with yaws-suspected skin lesions during three outbreaks, two of which occurred in 2017 and one in 2019. DNA extracted from the swabs was used to amplify three target genes: the human β2-microglobulin gene to confirm proper sample collection and DNA extraction, the polA gene, highly conserved among all subspecies of T. pallidum, and the hddA gene of H. ducreyi. A fourth target, the tprL gene was used to differentiate T. p. pertenue from the other agents of human treponematoses in polA-positive samples. A total of 112 samples were analysed in this study. One sample, negative for β2-microglobulin, was excluded from further analysis. T. p. pertenue was only detected in the samples collected during the first 2017 outbreak (12/74, 16.2%). In contrast, H. ducreyi DNA could be amplified from samples from all three outbreaks (outbreak 1: 27/74, 36.5%; outbreak 2: 17/24, 70.8%; outbreak 3: 11/13, 84.6%). Our results show that H. ducreyi was more frequently associated to skin lesions in the examined children than T. p. pertenue, but also that yaws is still present in Cameroon. These findings strongly advocate for a continuous effort to determine the aetiology of ulcerative skin lesions during these recurring outbreaks, and to inform the planned mass treatment campaigns to eliminate yaws in Cameroon.

Author summary

Yaws caused by Treponema pallidum pertenue is one of the most prevalent skin ulcer diseases among children in tropical and sub-tropical countries in Africa and the South-Pacific region. In Cameroon, outbreaks of yaws occur among populations living in remote areas where health infrastructure is lacking. The yaws diagnosis is frequently made clinically, even though rapid and simple serological assays were also introduced to confirm active yaws infection. Lately, studies using molecular amplification assays and performed in the South Pacific and Ghana reported that apart from T. p. pertenue, Haemophiluys ducreyi is also detected in children presenting with yaws-like lesions. This study was performed in the context of the surveillance of yaws in the East and South region of Cameroon. Molecular tools were used to detect and confirm the presence T. p. pertenue in samples suspected of yaws and collected during three outbreaks of ulcerative skin lesions among children in Cameroon. In addition, all samples were analysed for H. ducreyi. We found that H. ducreyi was present in samples from all three outbreaks, but T. p. pertenue was only detected among samples collected during the first outbreak. We concluded that yaws was present in Cameroun but that not all outbreaks of yaws-like skin lesions were attributable to T. p. pertenue infection.

Introduction

Outbreaks of ulcerative skin lesions are frequently reported in several countries in the Pacific region, South East Asia, and West and Central Africa [1,2], including Cameroon. These lesions most commonly affect children and young adults in rural and remote communities, and are frequently found on the lower extremities, which are areas often subject to skin injuries and abrasions that might serve as an entry site for bacteria [1–3], such as the one causing yaws [4] and Haemophilus ducreyi.

Yaws is a neglected tropical skin disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum subspecies pertenue that is spread through skin-to-skin contact. T. p. pertenue is closely related to the syphilis spirochete, T. p. pallidum [1], as these pathogens differ by less than 0.2% of their genome sequences [5]. T. p. pertenue causes, similar to T. p. pallidum, a multistage disease characterised by an ulcer in the primary stage. Yaws typically starts with the appearance of a papule, mostly found on the lower limbs, evolving to a papilloma and subsequently into an ulcer which will heal over time. The ulcers may occur either as single or multiple, although the latter is more frequent during the second stage of the disease [6]. The treponemes spread through the bloodstream and secondary lesions may appear on different body locations such as face, neck, arms, and on the soles of the feet, with the latter causing a crab-like gait in the patient due to hyperkeratotic pedal plaques and secondary infections. If untreated, following resolution of the early symptoms, the infection will become latent. During latency there are no physical signs and consequently can only be detected by serology. Overall 10% of the untreated infected individuals will progress to the tertiary stage, which is non-infectious but destructive [1]. The bones, joints and soft tissues may be affected and the patients may suffer from irreversible disabilities such as for example chronic periostitis resulting in saber shin or destructive processes leading to the perforation of the palate and nasal septum [1,3].

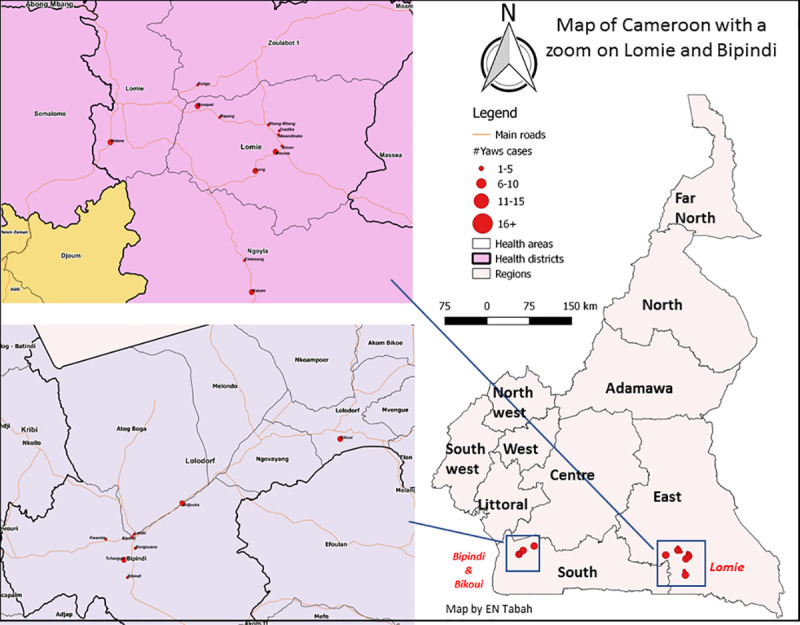

From 1950 till 2013 a total of 90 countries worldwide reported cases of yaws [2]. In the 1950s Cameroon reported more than 100,000 annual cases [2]. Aiming to eradicate yaws, mass treatment campaigns with benzathine penicillin G were organized by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in collaboration with the United National Children’s Fund between 1952 and 1964 [2,7,8]. As a result, by the end of the 1960s clinical yaws manifestations were no longer observed in Cameroon and the infection was thought to have been eliminated [2,9,10]. However, yaws continued to be present among the indigenous populations living in the tropical forests, and outbreaks were reported in 2007 and 2008 in the Lomié health district located in the East Province of Cameroon [11] (Fig 1). An epidemiological survey carried out in 2009 in the district of Lomié, reported 167 cases of yaws [9]. The number of reported yaws cases in Cameroon declined from 802 in 2010 to 97 in 2013, but increased thereafter from 530 in 2014 to 890 in 2016 [12].

Fig 1. Geographic location of sampling sites.

Samples were collected from lesions by rotating the sterile tip of the swab gently on the base and centre areas of the lesion. The swab type, storage and transport conditions differed between the epidemiological investigations. During the first outbreak, flocked swabs stored in 1 ml Amies transport medium (Eswab, Copan Diagnostics Inc., Brescia, Italy) were used. In the second outbreak, samples were collected us2ing the Abbott multi-Collect Specimen Collection Kit (Abbott, Des Plaines, IL, USA) which includes 1.2 mL of specimen transport buffer. During the last investigation, cotton-tipped swabs with wooden shaft (Copan Diagnostics Inc) were used for sample collection and stored dry until use. All samples were transported refrigerated to the Centre Pasteur du Cameroun (CPC) in Yaounde. Samples were stored as received at -20°C until testing. Blood samples were collected for serology to determine the presence of non-treponemal and treponemal antibodies.

Haemophilus ducreyi is a fastidious small Gram-negative coccobacillus. It is known to be a sexually transmitted pathogen causing genital ulcers called chancroid. Although chancroid has almost disappeared globally, interest on H. ducreyi has re-emerged as this pathogen is a cause of childhood skin ulcers. This pathogen has in fact been known since 1889 to cause skin lesions. August Ducreyi observed the development of papules and ulcers when purulent material collected from chancroid lesions was inoculated on the skin of patients’ forearms [13]. A century later, Quale et al. [14] reported a case of chancroid in an HIV infected man who presented multiple lesions on his legs and foot probably resulting from autoinoculation. Since then, H. ducreyi has been reported as cause of yaws-like skin ulcers on mainly the lower limbs of children residing in the South Pacific islands and Ghana [15–18].

Although our work focuses on T. p. pertenue and H. ducrey, it is worth mentioning that other microbes may also cause skin ulcers, such as Mycobacterium ulcerans (the agent of Buruli ulcer), as well as anaerobes and Gram-positive cocci causing a tropical ulcer of polymicrobial etiology. Leishmania species cause cutaneous leishmaniasis which is a non-bacterial skin ulcer. Skin ulcers may also have a non-infectious cause such as in the case of a vascular, a neuropathic, or a traumatic ulcers [19].

To better understand the role played by T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi in the aetiology of skin ulcers among children residing in yaws endemic regions in Cameroon, we analysed skin lesion samples collected in the context of three yaws-like outbreaks among children in 2017 and 2019 using nucleic acid amplification tests targeting T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi. Our results will inform Public Health officials in Cameroon and other stakeholders in charge of the national surveillance of neglected tropical diseases and the implementation of the national mass drug administration (MDA) programmes that might help reduce the incidence of this serious condition.

Methods

Ethics statement

We did not seek additional ethical clearance as the analysis were done in the context of the national skin ulcer lesion surveillance approved by the National Committee on Research Ethics for Human Health (approval reference 2016/08/800/CE/CNERSH/SP). No supplementary data was collected. All parents/ guardians provided oral consent and voluntary opted into the sampling of their children for surveillance purposes. All individuals were managed and treated according to the national Cameroonian guidelines and in line with the WHO recommended guidelines for “Total Targeted Treatment” of yaws [20].

Sample collection

Samples were collected from skin lesions that occurred in children during two outbreaks in the Lolodorf and Lomie health districts in the South and East regions of Cameroon, respectively, in 2017 and one outbreak in Lolodorf health district 2019 (Fig 1).

Serology

During the first outbreak, finger prick blood was tested using rapid diagnostic assays. The SD Bioline Syphilis 3.0 (Standard Diagnostics Inc, Suwon, Korea) was used to determine the presence of treponemal antibodies, while the Dual Path Platform (DPP) Screen and Confirm Assay (Chembio Diagnostic Systems Inc, NY, USA) to confirm the presence of an active infection based on the simultaneous detection of both treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies.

Rapid diagnostic tests were not available during the second and third outbreak. Therefore venous blood was collected and tested using the Architect Syphilis TP Assay (Abbott Laboratories, Des Plaines, IL, USA), that detects treponemal antibodies. If positive, the serum was then tested by TPHA (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) to confirm the initial result and a non-treponemal test to confirm an active infection (RPR; RPR-nosticon II, BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France).

Nucleic acid amplification

Sample processing

Swabs stored dry were thawed at room temperature and biological material was eluted in 500μL lysis buffer (10mM Tris pH 8.0, 0.1M EDTA pH 8.0, 0.5% SDS). All samples were vigorously vortexed for at least 15 seconds and the swabs were pressed against the tube to ensure that most biological material was released in the lysis buffer or transport medium.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 200 μL of the samples employing the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol for DNA purification from blood and body fluids, with the exception that a) 50 μL proteinase K were added to the samples instead of 20 μL, b) samples were incubated for 1–2 hours at 56°C, and c) 220 μL of AL buffer and 210 μL of 96–100% ethanol were added instead of the suggested 200 μL to compensate for a slightly larger initial sample volume (200 μL instead of 180 μL).

Polymerase chain reactions

The presence of host DNA and the absence of amplification inhibitors in the extracted DNA were evaluated by the amplification of a 268-bp fragment of the β2-microglobulin gene. The targeted fragment of the polA (tp0105) gene, conserved present in all subspecies of T. pallidum was amplified by real time PCR (qPCR) to detect the presence of T. pallidum DNA in the samples. In polA–positive samples T. p. pertenue DNA was identified based on the amplicon size of the tprL target (tp1031) which differentiates the yaws pathogen from the other agents of human treponematoses. The amplicon size is +/-209 bp for T. p. pertenue, in contrast to the amplicon size of +/-588 bp for T. p. pallidum. The amplicon sizes were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis. H. ducreyi DNA was detected by amplifying a target of the hhdA gene coding for haemolysin. Amplification was performed by qPCR. Primers and probes were synthesized by GenScript, USA. All amplification assays contained positive controls consisting of DNA extracts of T. pallidum obtained after culture in a rabbit model and of H. ducreyi cultured on agar plates, and a negative control consisting of molecular grade water. In addition, we included environmental DNA checks to control for laboratory area contamination. Each sample was run in duplicate. The PCR methods are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Polymerase chain reactions.

| Target gene | PCR Method | Reaction volume (μL) | DNA volume (μL) | Reagent mixture | Primers/probes (reference) | Cycling conditions | Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2-micro globulin | End point | 50 | 5 | Go Taq Green Buffer 1X, GoTaq polymerase 0.05U (Promega, USA), 200 μM dNTPs (Invitrogen, USA), 1.5mM MgCl2 (ThermoScientific, USA) | 320 nM GH20 320 nM PC04 [21] | 3 min 95°C,40x (1 min 95°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C)5 min 72°C, hold 15°C | Applied Biosystem geneAmp 9700 |

| polA | Real time | 25 | 5 | ABI Taqman FAST Advanced Master Mix (Life Technologies Corporation, USA) | 1.2μM TP1, 1.2μM TP2 180 nM TP31 [22] | 2 min 50°C, 30 sec 95°C, 50x (20 sec 95°C, 45 sec 60°C) | ABI PRISM 7500 |

| tprL | End point | 50 | 5 | Go Taq Green Buffer 1X, GoTaq polymerase 0.05U (Promega, USA), 200 μM dNTPs (Invitrogen, USA), 1.5mM MgCl2 (ThermoScientific, USA) | 320 nM TprLpertS 320 nM TprLpert [23] | 5 min 95°C,45x (1 min 95°C, 1 min 60°C, 1 min 72°C)10 min 72°C, hold 15°C | Applied Biosystem geneAmp 9700 |

| hhdA | Real time | 25 | 5 | Taqman Universal Master Mix (Life Technologies Corporation, USA) | 400 nM HhdA-F, 600nM HhdA-R 400 nM HhdA-P1 [24] | 2 min 50°C, 10 min 95°C, 45x (20 sec 95°C, 1 min 60°C) | ABI PRISM 7500 |

1 The TP3 probe was HEX labelled; HhdA-P probe was JOE labelled.

Definition

An confirmed yaws infection was defined based on the presence of T. p. pertenue DNA.

Data analysis

All data were entered twice in Excel worksheets (see S1 Data) and verified for data entry errors. Simple descriptive statistics were used to summarise patient and sample characteristic, and amplification analysis results. The proportion of boys and girls with T. p. pertenue DNA and H. ducreyi DNA, respectively, were compared using Fisher’s exact tests. The difference in age distribution of children with T. p. pertenue DNA and H. ducreyi DNA, respectively, were assessed by using a t-test. Significance level was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed in PSPP, an open source version of SPSS.

Results

Study population

A total of 114 individuals presenting skin lesions contributed to 112 skin lesion samples: two distinct lesions were sampled in two individuals and lesion samples went missing from four individuals. The distribution of the samples according to the period and location of the outbreak, the age and gender of the individuals and location of the skin lesion is presented in Table 2. The patients’ age ranged from 1 to 18 years (median age of 9 years) and 66 children (60%) were male. Of the four individuals from whom skin lesion samples were lacking, three were girls and their age ranged from 8 to 13 years.

Table 2. Distribution of the samples according the outbreak’s location, age and gender of the individuals contributing to the samples and location of the skin lesions.

| Outbreak 1 | Outbreak 2 | Outbreak 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | September 2017 | December 2017 | August-Octobre 2019 |

| Location | Lomie HD | Bipindi, Lolodorf HD | Bikoui, Lolodorf HD |

| Number of samples | 75 | 24 | 13* |

| Number of individuals | 75 | 24 | 11 |

| Age Median (IQR) | 8 (4–11) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (7–15.5) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 49 | 11 | 6 |

| Female | 26 | 13 | 5 |

| Location skin lesion | |||

| Lower limb | 53 | 9 (foot) | |

| Upper limb | 3 | ||

| Multiple** | 15 | ||

| Trunk | 2 | ||

| Head | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 24 | 4 |

| Type of skin lesion | |||

| Ulcer | 60 | NS | 13 |

| Papilloma | 13 | ||

| Papule | 1 | ||

| Keratosis | 1 |

* 2 individuals contributed to 2 samples each, both were girls, 15 and 16 years old.

** Multiple: includes lesions on the lower limb; upper limb; among others.

IQR: inter quartile range; HD: health district; NS: not specified.

Serodiagnosis

Rapid diagnostic tests were employed for the detection of treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies during the first outbreak. A total of 75 children were tested. Treponemal antibodies were detected by both rapid diagnostic assays, SD bioline and DPP Chembio, in 22/75 (29.3%) individuals. In addition, non-treponemal antibodies were demonstrated in 19 of them.

None of the serum samples collected during outbreak 2 and 3 had a positive serology for treponemal infection; the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Presence of treponemal and non-treponemal antibodies in serum samples collected in the context of the three outbreaks.

| Serology | Outbreak 1 N = 75 (%) |

Outbreak 2 N = 24 (%) |

Outbreak 3 N* = 7 (%) |

Total N = 106 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treponemal antibodies | 22 (29.3) | 0 | 0 | 22 (20.8) |

| Non Treponemal antibodies | 19 (25.3) | 0 | 0 | 19 (17.9) |

*4 blood samples were not collected.

Detection of Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue and Haemophilus ducreyi DNA

One sample out of the 112 samples was excluded from further analysis due to the absence of the amplification of the β2-microglobulin gene. The results according to the outbreak are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Presence of T.

pallidum, T. pallidum pertenue and H. ducreyi DNA in samples collected in the context of the three outbreaks.

| PCR target | Outbreak 1 N* = 74 (%) |

Outbreak 2 N = 24 (%) |

Outbreak 3 N = 13 (%) |

Total N = 111 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| polA | 14 (18.9) | 0 | 0 | 14 (12.6) |

| tprL | 12 (16.2) | NT | NT | 12 (10.8) |

| hhdA | 27 (36.5) | 17 (70.8) | 11 (84.6) | 55 (49.6) |

* 1 sample was excluded from further analysis as β2-microglobulin could not be detected NT: not tested.

Treponemal DNA was detected only among the samples collected during outbreak 1 (14/74, 18.9%). T. p. pertenue DNA was identified in 12 polA-positive samples. H. ducreyi DNA was detected in samples collected in all three outbreaks: in 36.5%, 70.8% and 84.6% of the samples collected during outbreak 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Only one sample contained both T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi DNA

There was no statistical difference in age distribution of children with confirmed yaws lesions compared to children with H. ducreyi lesions. Yaws and H. ducreyi lesions were more frequently detected among boys compared to girls but none of the differences were statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5. Characteristics of children with PCR confirmed yaws (T. p. pertenue) and with H. ducreyi lesions.

| Outbreak 1 | Outbreak 2 | Outbreak 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T p pertenue | N = 12 | N = 0 | N = 0 |

| Median age (IQR) | 6 (3.5–9.25) | ||

| Gender | |||

| M (%) | 9/48 (18.7) | ||

| F (%) | 3/26 (11.5) | ||

| H ducreyi | N = 27 | N = 17 | N = 9** |

| Median age (IQR)* | 8 (4–10) | 10 (9–11) | 11(9–16) |

| Gender | |||

| M (%) | 18/48 (37.5) | 9/11 (81.8) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| F (%) | 9/26 (34.6) | 8/13 (61.5) | 4/5 (80) |

*IQR: interquartile range; N: number; M: male; F: female; outbreak 3:

**Each individual was counted once but 2 individuals contributed to 2 samples each, both were girls, 15 and 16 years old. H. ducreyi DNA was detected in the four samples.

Serology and presence of Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue and Haemophilus ducreyi DNA, data of outbreak 1 only

Non-treponemal antibodies, in the presence of treponemal antibodies, were not detected in three children presenting skin lesions in which T. p. pertenue DNA was detected and treponemal antibodies were absent in two children with PCR confirmed yaws lesions. On the other hand, T. p. pertenue DNA could not be detected in skin lesions of 12 individuals presenting a positive serology (Table 6).

Table 6. Number of samples with positive and negative polA qPCR, tprL PCR and hhdA qPCR results versus serology results, outbreak 1.

| Serology | polA | tprL | hhdA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

+ N = 14 |

- N = 58 |

+ N = 12 |

- N = 2 |

+ N = 27 |

- N = 45 |

|

| Treponemal +, Non Treponemal + N = 19 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 14 |

| Treponemal +, Non Treponemal—N = 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Treponemal–N = 50 | 3 | 47 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 28 |

Note: For what concerns the PCR results of polA and hhdA: a total of 75 samples were collected, however the results presented do not tally due to invalid results in serology or because samples containing inhibitors were not tested by PCR.

H. ducreyi was detected in 27 skin lesion samples. Five H. ducreyi infected children had a positive serology for treponemal infection, in one of them T. p. pertenue was amplified from the skin lesion and in another T. pallidum DNA was detected but T. p. pertenue could not be confirmed.

Discussion

This is the first time that amplification assays to detect T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi were employed in Cameroon. Although we were able to confirm the presence of yaws in this country, not all yaws-like skin lesions sampled were however attributable to yaws, as T. p. pertenue DNA was not detected in the samples collected during the two most recent outbreaks. Conversely, H. ducreyi DNA was detected in almost half (49.6%; 55/111) of the samples collected during all three outbreaks.

We found more than twice the number of H. ducreyi-positive samples (36.5%) compared to the ones positive for T. p. pertenue (16.2%) in the specimens from the first outbreak, which is similar to the findings of a study conducted in Papua New Guinea [17]. In that study, Mitjà et al, found almost twice as much of H. ducreyi (60%) compared to T. p. pertenue (34%) in exudative ulcer material collected from children and young adults [17]. Only H. ducreyi DNA was detected in the samples collected during the last two outbreaks. This is in agreement with the results obtained previously in two cross sectional studies performed in the Solomon Islands and Ghana, albeit that we found a much higher proportion of samples with H. ducreyi (71% and 85%, detected in outbreak 2 and 3, respectively, compared to 32% and 8% obtained in the Solomon Island and Ghana, respectively) [15,18].

Since the first report of H. ducreyi identified in chronic lower limb ulcers in three independent travellers to Samoa [25], evidence of the causative relationship between this pathogen and chronic lower limb ulceration in children and (occasionally) in adults increased significantly [17,18,26,27]. Consequently, nowadays H. ducreyi is widely recognized as a causative agent of skin ulcers. However, H. ducreyi has also been detected on the skin of asymptomatic children and in environmental samples such as on linen and flies [28]. Therefore, it remains difficult to distinguish infection from colonisation or contamination. We cannot be certain that H. ducreyi is the main etiological cause of the ulcer where this pathogen was detected, rather than a contaminant from the adjacent colonised skin or environment. We can however exclude sample contamination from laboratory sources, as no H. ducreyi DNA was present in the environmental controls obtained from laboratory surfaces.

We did not observe significantly more H. ducreyi skin lesions among males (49.2%) compared to females (47.7%), which is consistent with previous reports but not with the outcome seen in human infection models [29]. Namely, it was observed that after inoculation of H. ducreyi in the skin of human volunteers, men and women formed papules at an equal rate, but that pustules, which erode into ulcers, were twice more frequent among men.

Our results confirm previously reported findings that H. ducreyi is frequently present in childhood cutaneous ulcers in yaws endemic, and possible also non-endemic regions. Future research is needed to confirm whether H. ducreyi is a pathogen, pathobiont or commensal. At present, we do not know what the findings of skin colonisation and ubiquitously presence of H. ducreyi in the environment means in terms of reservoir, infection’s risk and ways of transmission.

Yaws is endemic in Cameroon and the low number of T. p. pertenue detected in the childhood skin ulcers came as a surprise. Since 2013, the number of reported yaws cases raised consistently until 890 cases in 2016 [12]. We analysed samples collected in 2017 in Lomié, the same region where yaws was reported during 2007–2011, and found T. p. pertenue in less than one fifth of the yaws-like lesions. We hypothesise that the number of previously reported yaws cases may be overestimated especially if the diagnosis was based solely on clinical appearance [9].

T. p. pertenue DNA was not detected in the clinically suspected yaws ulcerations observed during the most recent two outbreaks. The lack of T. p. pertenue in these samples corroborated the non-reactive treponemal serology, indicating that these individuals were not infected with T. p. pertenue or other agents of human treponematoses at the time of testing nor were they exposed to treponemal infections in the past. Our results also illustrate how difficult it is to clinically diagnose yaws skin ulcers. In order to improve the accuracy of the diagnosis of yaws, molecular assays should be used for the detection of T. p. pertenue in yaws-like lesions.

We could not confirm the diagnosis of yaws by molecular amplification of T. p. pertenue DNA target although T. pallidum DNA was detected. This is most probably due to differences in the limit of detection of the two amplification techniques. T. pallidum DNA is detected using qPCR, whereas the subspecies pertenue is identified based on the size of the tprL amplicon obtained by qualitative PCR, with the latter method being less sensitive. Consequently, samples with a low concentration of Treponema pallidum DNA may be missed when the tprL gene is targeted by PCR. However, we do not believe that these two cases were actual syphilis cases. Based on the location of the lesions (legs), the age of the children (10 and 11 years), and the rarity of extragenital, non-sexual transmission of syphilis among children, it is very unlikely that these two cases were due to syphilis infection. However, we cannot exclude that the two children were infected with T. p. subspecies endemicum, as both bejel and yaws are transmitted by skin-to skin contact and affect similar demographic groups. However, bejel was never previously reported in Cameroun. Furthermore, the localization of the skin lesions does not support the diagnosis of bejel. Ulcers associated with bejel are usually located in the oral cavity or nasopharynx. Whereas the two patients had skin lesions on the lower limb and trunk, which is more typical of yaws infection.

Treponemal and non-treponemal tests are used to confirm active yaws cases in the absence of molecular assays. Active yaws is defined based on the simultaneous presence of non-treponemal and treponemal antibodies, identical to the definition and serological diagnosis of active syphilis. During the first outbreak, rapid diagnostic tests using finger prick blood were employed. The number of active yaws cases based on reactive serology results (N = 22) was higher than the number of PCR confirmed yaws cases (N = 12). We may explain these findings by the fact that a) the reactive serology may indicate a previously treated or latent yaws infection and not the current cause of the skin lesion; b) the ulcers may be healing and consequently have no detectable T. p. pertenue, or c) only one ulcer per individual was sampled even in the presence of multiple skin ulcers, which may have decreased the probability to detect T. p. pertenue [15]. On the other hand, five confirmed yaws cases (based on molecular testing) would have been missed using only serology [30]. Three of them were not considered as active yaws based on the lack of reactivity of the non-treponemal test line in the rapid test. This could be due to the lower sensitivity of the DPP test especially for lower RPR titres or to the delayed non-treponemal antibody response observed in early infections [31,32]. It may therefore be recommended to use an automated reader which reports the intensity of the lines in a standardized and objective manner and which has previously be shown to increase the sensitivity of the non-treponemal test line of the DPP RDT [17].

WHO renewed in 2012 its goal to eradicate yaws by 2020 and established a strategy, to meet this target [33]. One of the pillars of this strategy is mass drug administration (MDA) campaigns like the one planned in Cameroon, during which azithromycin will be administered to the entire population of a yaws endemic area. Following MDA, repeat surveys will be organized to identify and treat new cases. Azithromycin is effective against T. p. pertenue and H. ducreyi, but caution is required as T. p. pertenue may develop resistance [34] and H. ducreyi may persist on the skin as a member of the skin microbiome. Consequently, reinfection may occur if traumas that compromise the integrity of the skin occur while the subject is no longer protected by antibiotic administration [28]. Indeed, a recent systematic review on the epidemiology of H. ducreyi concluded that one round of MDA may not be enough to eradicate the appearance of skin ulcers caused by this pathogen [26]. In addition, recent data about the possible emergence of azithromycin resistance among H. ducreyi is lacking [35]. All this considered, MDA may be effective in eradicating of yaws skin ulcers among children, but may overtime be less effective for H. ducreyi ulcers which strongly advocates for a continuous surveillance program using molecular diagnostic tools including detection of azithromycin resistance associated mutations.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the medical and non-medical staff involved in the surveillance activities of the national Yaws control programme.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was realised thanks to financial support from WHO and Probitas. Both contributed to the additional purchase of reagents and consumables for the molecular assays employed. The financial sponsors had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Giacani L, Lukehart SA. The endemic treponematoses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:89–115. 10.1128/CMR.00070-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazadi WM, Asiedu KB, Agana N, Mitjà O. Epidemiology of yaws: an update. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:119. 10.2147/CLEP.S44553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitjà O, Asiedu K, Mabey D. Yaws. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):763–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupi O, Madkan V, Tyring SK. Tropical dermatology: Bacterial tropical diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006;54:559–78. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Čejková D, Zobaníková M, Chen L, Pospíšilová P, Strouhal M, Qin X, et al. Whole genome sequences of three Treponema pallidum ssp. pertenue strains: Yaws and syphilis treponemes differ in less than 0.2% of the genome sequence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(1). 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker SL, Hay RJ. Yaws—A review of the last 50 years. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(4):258–60. 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savioli L, Daumiere D. Accelerating Work to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Roadmap for Implementation (World Health Organizaton, Geneva, Switzerland, 2012). 2012;42. Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/NTD_RoadMap_2012_Fullversion.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maurice J. WHO plans new yaws eradication campaign. The Lancet. 2012;379:1377–8. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60581-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabah EN, Boock AU. Yaws in the Lomie health district of the East Region of Cameroon in: WHO Annual Meeting on Buruli ulcer, Geneva, 22–24 March 2010:Abstracts p121-123.

- 10.Guthe T, Ridet J, Vorst F, D’Costa J, Grab B. Methods for the surveillance of endemic treponematoses and sero-immunological investigations of “disappearing” disease. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(1):1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Summary report of a consultation on the eradication of yaws 5–7 March 2012, Morges, Switzerland. 2012.

- 12.WHO. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Status of endemicity for yaws. [cited 2020 Jun 11]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.%0ANTDYAWSEND?lang=en%0A.

- 13.Albritton WL. Biology of Haemophilus ducreyi. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53(4):377–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quale J, Teplitz E, Augenbraun M. Atypical presentation of chancroid in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med 1990;88(5N):43N–44N. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghinai R, El-Duah P, Chi KH, Pillay A, Solomon AW, Bailey RL, et al. A Cross-Sectional Study of ‘Yaws’ in Districts of Ghana Which Have Previously Undertaken Azithromycin Mass Drug Administration for Trachoma Control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9(1):1–9. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chi KH, Danavall D, Taleo F, Pillay A, Ye T, Nachamkin E, et al. Molecular differentiation of Treponema pallidum subspecies in skin ulceration clinically suspected as yaws in Vanuatu using real-time multiplex PCR and serological methods. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92(1):134–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitjà O, Lukehart SA, Pokowas G, Moses P, Kapa A, Godornes C, et al. Haemophilus ducreyi as a cause of skin ulcers in children from a yaws-endemic area of Papua New Guinea: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Heal 2014;2(4):235–41. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks M, Chi K-H, Vahi V, Pillay A, Sokana O, Pavluck A, et al. Haemophilus ducreyi Associated with Skin Ulcers among Children, Solomon Islands. Emerg Infect Dis 2014;20(10):1705–7. 10.3201/eid2010.140573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzáles-Beiras C, Ubals M, Corbacho-Monné M, Vall-Mayans M, Mitjà O. Yaws, Haemophilus ducreyi, and other bacterial causes of cutaneous ulcer disease in the South Pacific Islands. Dermatol Clin. 2021. January;39(1):15–22. 10.1016/j.det.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Eradication of yaws: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. (WHO/CDS/NTD/IDM/2018.01) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnick R, Cornelissen M, Wright D, Eichinger G, Fox H, ter Schegget J, et al. Detection and typing of human papillomavirus in archival cervical cancer specimens by DNA amplification with consensus primers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(18):1477–84. 10.1093/jnci/82.18.1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C-Y, Chi K-H, George RW, Cox DL, Srivastava A, Rui Silva M, et al. Diagnosis of gastric syphilis by direct immunofluorescence staining and real-time PCR testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(9):3452–6. 10.1128/JCM.00721-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centurion-Lara A, Giacani L, Godornes C, Molini BJ, Brinck Reid T, Lukehart SA. Fine analysis of genetic diversity of the tpr gene family among Treponemal species, subspecies and strains. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7(5):e2222. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C-Y, Ballard RC. The molecular diagnosis of sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;903:103–12. 10.1007/978-1-61779-937-2_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ussher JE, Wilson E, Campanella S, Taylor SL, Roberts SA. Haemophilus ducreyi Causing Chronic Skin Ulceration in Children Visiting Samoa. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(10):e85–7. 10.1086/515404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.González-Beiras C, Marks M, Chen CY, Roberts S, Mitjà O. Epidemiology of Haemophilus ducreyi infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22(1):1–8. 10.3201/eid2201.150425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fegan D, Glennon MJ, Kool J, Taleo F. Tropical leg ulcers in children: more than yaws. Trop Doct 2016;46(2):90–3. 10.1177/0049475515599326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houinei W, Godornes C, Kapa A, Knauf S, Mooring EQ, González-Beiras C, et al. Haemophilus ducreyi DNA is detectable on the skin of asymptomatic children, flies and fomites in villages of Papua New Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(5):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janowicz DM, Ofner S, Katz BP, Spinola SM. Experimental Infection of Human Volunteers with Haemophilus ducreyi: Fifteen Years of Clinical Data and Experience. J Infect Dis 2009;199(11):1671–9. 10.1086/598966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gayet-Ageron A, Lautenschlager S, Ninet B, Perneger TV, Combescure C. Sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios of PCR in the diagnosis of syphilis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013. May;89(3):251–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hy Li, Soebekti R. Serological study of yaws in Java. Bull World Health Organ 1955;12(6):905–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langendorf C, Lastrucci C, Sanou-Bicaba I, Blackburn K, Koudika M-H, Crucitti T. Dual screen and confirm rapid test does not reduce overtreatment of syphilis in pregnant women living in a non-venereal treponematoses endemic region: a field evaluation among antenatal care attendees in Burkina Faso. Sex Transm Infect. 2019; 95(6):402–404. 10.1136/sextrans-2018-053722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. Eradication of Yaws- the Morges strategy. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87(20):189–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smajs D, Paštěková L, Grillová L. Macrolide resistance in the Syphilis Spirochete, Treponema pallidum ssp. pallidum: can we also expect macrolide-resistant Yaws strains? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015; 93: 678–683. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis D. Epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of Haemophilus ducreyi–a disappearing pathogen?, Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2014;2(6): 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]