A MAJOR PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

COVID-19 continues to impact heavily on the world’s children, including their education, health, and social life. Bullying, which harms each of these domains of childhood development, may have substantially increased during the ongoing pandemic, compounding further the disproportionate impact on children and young people.

Bullying in childhood and adolescence is a major public health problem that has affected one in three children across countries of all incomes in the preceding month.1 The increased risk of poor health, educational, and social outcomes associated with bullying are well recognised in childhood, and are now known to extend into adult life.2,3

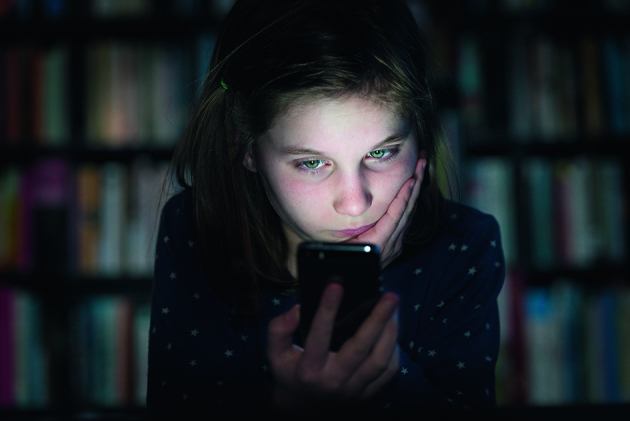

In addition to traditional forms including physical, verbal, and psychological bullying, cyberbullying represents a relatively new phenomenon in which bullying takes place through digital modalities.

TRADITIONAL BULLYING AND CYBERBULLYING

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable to cyberbullying victimisation due to their almost ubiquitous uptake of smartphones and participation in social media. The increased potential for large audiences and anonymous attacks, coupled with the permanence of posts and reduced adult supervision, render cyberbullying a significant threat to child mental health. However, at least prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, cyberbullying had a much lower prevalence than, and created very few additional victims beyond, traditional forms of bullying.4

National lockdowns and widespread school closures triggered by COVID-19 substantially increased the online activity of millions of children and adolescents globally. Such conditions provided the opportunity for potentially increased rates of cyberbullying victimisation while traditional forms of bullying were rendered unfeasible.

In addition to existing traditional methods converting to digital forms, entirely new victims of bullying may have been targeted through elevated cyberbullying activity due to increased time spent online. These additional victims may face bullying in both traditional and digital modalities once schools reopen worldwide.

Consequently, there now exists a potential burden of childhood and adolescent bullying that is significantly greater than that prior to COVID-19. Without meaningful action, this could lead to increased rates of poor health, educational, and social outcomes in childhood that endure for decades.

COOPERATIVE LEARNING APPROACHES OFFER THE GREATEST POTENTIAL FOR SUCCESS

Research is urgently needed to establish the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of all forms of childhood and adolescent bullying, and meaningful interventions installed in anticipation of elevated levels. These could initially focus on teenage girls, who are at a greater risk of cyberbullying, and of the associated poor mental health outcomes, rather than boys.5 However, traditional bullying is likely to remain the major form associated with such outcomes, meaning bullying prevention programmes shouldn’t focus solely on digital modalities.

While evidence-based anti-bullying interventions are lacking, cooperative learning approaches offer the greatest potential for success, although implementation will be challenging under current physical distancing restrictions.6

Finally, health professionals working with children and adolescents, particularly those in general practice, should be alerted to the potential increased rates of bullying, and the likely impact on child and adolescent health.

Footnotes

This article was first posted on BJGP Life on 28 January 2021: https://bjgplife.com/bullying

REFERENCES

- 1.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. 2019 https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483/PDF/366483eng.pdf.multi (accessed 5 Feb 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, et al. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klomek AB, Sourander A, Elonheimo H. Bullying by peers in childhood and effects on psychopathology, suicidality, and criminality in adulthood. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(10):930–941. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolke D, Lee K, Guy A. Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(8):899–908. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-0954-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Przybylski AK, Bowes L. Cyberbullying and adolescent well-being in England: a population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Ryzin MJ, Roseth CJ. Cooperative learning in middle school: a means to improve peer relations and reduce victimization, bullying, and related outcomes. J Educ Psychol. 2018;110(8):1192–1201. doi: 10.1037/edu0000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]