Abstract

Excessive lung inflammation caused by endotoxins, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS), mediates the detrimental effects of acute lung injury (ALI), as evidenced by severe alveolar epithelial cell injury. CD40, a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, serves as a central activator in triggering and transducing a series of severe inflammatory events during the pathological processes of ALI. Ginkgolide C (GC) is an efficient and specific inhibitor of CD40. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate whether GC alleviated LPS-induced ALI, as well as the potential underlying mechanisms. LPS-injured wild-type and CD40 gene conditional knockout mice, and primary cultured alveolar epithelial cells isolated from these mice served as in vivo and in vitro ALI models, respectively. In the present study, histopathological assessment, polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN) infiltration, lung injury score, myeloperoxidase activity, wet-to-dry (W/D) weight ratio and hydroxyproline (Hyp) activity were assessed to evaluate lung injury. In addition, immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate intracellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression levels, and TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 ELISAs and western blotting were conducted to elucidate the signaling pathway. The results demonstrated that GC alleviated LPS-induced lung injury, as evidenced by improvements in ultrastructural characteristics and histopathological alterations of lung tissue, inhibited PMN infiltration, as well as reduced lung injury score, W/D weight ratio and hydroxyproline content. In LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells, GC significantly reduced IκBα phosphorylation, IKKβ activity and NF-κB p65 subunit translocation via downregulating CD40, leading to a significant decrease in downstream inflammatory cytokine levels and protein expression levels. In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrated that GC displayed a protective effect against LPS-induced ALI via inhibition of the CD40/NF-κB signaling pathway; therefore, the present study suggested that the CD40/NF-κB signaling pathway might serve as a potential therapeutic target for ALI.

Keywords: Ginkgolide C, CD40, acute lung injury, inflammation, NF-κB

Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is the pulmonary manifestations of an acute systemic inflammatory process that is characterized by pulmonary infiltrates, hypoxemia and edema, frequently resulting in significant morbidity and mortality (1,2). At present, the mechanism underlying ALI by driving an acute inflammatory response is not completely understood. Over the last few decades, although a large number of ongoing studies are evaluating the value of several new drugs, no effective drug has been identified (3). Therefore, understanding the exact mechanism and implicated factors may aid with identifying novel targets and strategies for the clinical prevention and treatment of ALI.

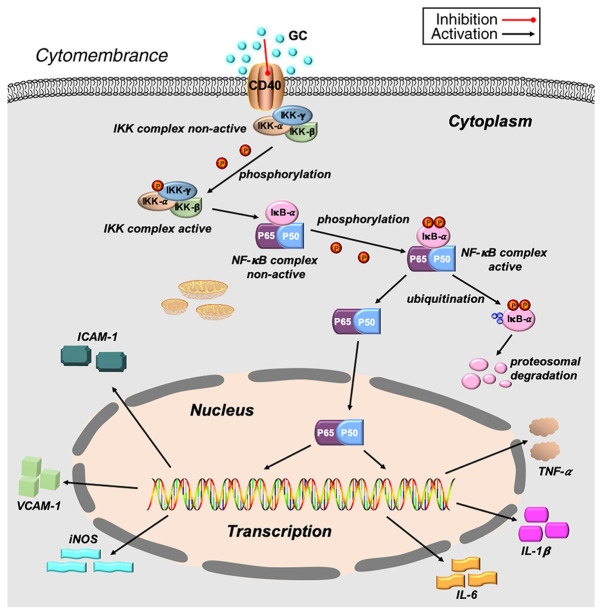

CD40 belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family and is involved in the onset and maintenance of inflammation (4,5). CD40 is present in a variety of cell types, including endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, macrophages and monocytes (6,7). Ligation of CD40 (CD40L) leads to activation of several inflammatory signaling pathways, including PI3K, MAPK, ERK1/2, IKK and NF-κB, eventually manifesting as enhanced expression of primarily proinflammatory genes and adhesion molecules (8). Therefore, CD40 may mediate the transcriptional regulatory genes encoding inflammatory factors via activation of NF-κB.

It was previously demonstrated that acute inflammation caused by NF-κB activation was associated with ALI, whereas lung injury was alleviated by NF-κB inhibition (9,10). The IKK complex, a crucial activator of NF-κB, consists of three proteins: i) IKK-α; ii) IKK-β; and iii) IKK-γ. The complex can be activated via IκB-α phosphorylation and subsequent degradation. The activated IKK complex phosphorylates the IκB protein, which results in proteasomal degradation. Subsequently, the NF-κB subunits translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes (11,12). Eventually, various inflammatory cytokines and proteins are stimulated, including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and cell adhesion molecules, such as intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), which can exacerbate the inflammatory damage to varying degrees (13,14).

In addition, another important pathological feature of ALI is infiltration and accumulation of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) in the interstitial and alveolar spaces of the lung, which impairs respiratory function (15). Persistent and extreme PMN infiltration may cause additional injury to the lung by promoting the release of several toxic factors, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), proinflammatory cytokines and procoagulant molecules, further aggravating ALI (16). Therefore, suppressing PMN infiltration may significantly decrease inflammation-induced damage and provide protection against ALI.

Ginkgo biloba is a traditional Chinese medicine that has been used for thousands of years, and its leaf extracts have been reported to display various biological properties, including cardioprotective, antineurovascular insult and anticancer activities (17). Our previous study reported that Ginkgolide C (GC), a flavonoid monomer extracted from Ginkgo biloba leaf with a range of biological activities, may protect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting CD40/NF-κB signaling and late inflammatory responses (18). However, the current understanding of the association between GC and ALI is limited and requires further investigation.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the protective effects of GC against ALI in vivo and in vitro, and to elucidate the potential underlying mechanism. The results of the present study may indicate novel therapeutic strategies and interventions for ALI. For example, the results indicated that CD40 might serve as a valuable therapeutic target for ALI.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

GC (PubChem CID: 161120) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA). TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 ELISA kits and anti-IKK-β antibody were purchased from Abcam. Anti-CD40, anti-ICAM-1, anti-VCAM-1, anti-iNOS, anti-NF-κB p65, anti-phosphorylated (p)-IκB-α, anti-IκB-α, anti-β-actin, anti-histone and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and RIPA lysis buffer were purchased from Abcam. PVDF membranes, the BCA protein concentration assay kit and the SDS-PAGE gel preparation kit were obtained from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The ECL plus kit was purchased from Cusabio Technology LLC.

Animals

A total of 48 male wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (age, 8-10 weeks; weight, 18-22 g; specific-pathogen-free grade) were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Shandong First Medical University. A total of 32 CD40 gene conditional knockout (CD40-cKO) male mice (age, 8-10 weeks; weight, 18-22 g; specific-pathogen-free grade) were provided by Biocytogen. All animals were housed at 20-25°C with 40-60% humidity, 12-h light/dark cycles, and free access to fresh water and food. Following lung tissue and blood collection, animals were sacrificed via cervical dislocation. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (grant no. 2020-464).

ALI induction in WT and CD40-cKO mice

A total of 40 mice were divided into five groups (n=8 per group; Table I) as follows: i) Control group, received PBS; ii) LPS group; iii) 12 mg/kg GC group, LPS mice received 12 mg/kg GC; iv) 24 mg/kg GC group, LPS mice received 24 mg/kg GC; and v) 48 mg/kg GC group, LPS mice received 48 mg/kg GC) (18). As previously described (19), mice were anaesthetized by the intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), orally intubated with a sterile plastic catheter and subsequently intratracheally administered LPS (5 mg/kg). At 24 h post-LPS treatment, mice were sacrificed. Control mice were intratracheally administered 50 µl PBS. In the GC groups, mice were intraperitoneally administered with GC for 7 days prior to LPS treatment. Prior to sacrifice, blood samples and lung tissues were collected under anesthesia.

Table I.

Animal groups included in the present study.

| Experiment | Group

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LPS | GC (12 mg/kg) | GC (24 mg/kg) | GC (48 mg/kg) | |

| LPS-injured WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice |

| LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice | WT mice |

| LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice | WT mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice |

| LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of CD40-cKO mice | WT mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice | CD40-cKO mice |

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; WT, wild-type; cKO, conditional knockout; GC, Ginkgolide C.

Histopathological assessment and PMN infiltration analysis

Following fixation in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, lung tissues were embedded in paraffin using an automated processor. After paraffin embedding, lung tissues were treated with a series of graded alcohols and xylene at 45°C for 10 min. Sections (6-µm thick) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin at 37°C for 15 min. Histopathological examination was performed using a BX51 light microscope (Olympus Corporation; magnification, ×200). The mean number of PMNs was recorded in three randomly selected high-power fields.

Evaluation of lung injury

The severity of lung injury was scored according to the alveolar wall thickness, the amount of cellular infiltration and the level of hemorrhaging, as previously described with minor modifications (20). Lung injury scores were graded on a scale of 0-8 as follows: 0, no damage; 2, mild damage; 4, moderate damage; 6, severe damage; and 8, extremely severe damage.

Determination of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

MPO activity in lung tissues was measured using an MPO kit (cat. no. 20190618; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) according to the manufacturer's protocol. MPO activity was expressed as U/g of protein.

Transmission electron microscopy

Lung tissues were fixed with glutaraldehyde buffered fixative (3%; pH 7.2) at 25°C for 2-3 days. Tissues were embedded in Spon 812 (SPI-Chem, Inc.; Structure Probe, Inc.) at 60°C for 48 h. Sections (thickness, 60-80 nm) were stained with 2% uranium acetate at 25°C for 10 min and lead citrate at 25°C for 5 min. Following washing with PBS, sections were analyzed using a JEM-2000EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Ltd.; magnification, ×17,000) in three randomly selected fields of view.

Measurement of lung wet-to-dry (W/D) weight ratio

Lung W/D weight ratio was calculated to assess the extent of lung edema/water accumulation. The wet lung weight was measured immediately after isolation from the mice. Following drying at 60°C for 24 h, the dry lung weight was measured.

Hydroxyproline (Hyp) assay

Hyp activity was determined using a Hyp Colorimetric Assay kit (BioVision, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunohistochemistry

To evaluate ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression in lung tissue, immunohistochemistry was performed. Lung tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 2 h and embedded in paraffin at 60°C for 2 h. Tissues were then blocked with 10% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) at 25°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections (thickness, 3-5 µm) were incubated with anti-ICAM-1 (cat. no. p05362), anti-VCAM-1 (cat. no. p29533) and anti-iNOS (cat. no. p35228) antibodies (all 1:800) overnight at 4°C. Following primary antibody incubation, the samples were incubated with an anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (cat. no. 3678s; 1:1,000) at 25°C for 30 min. The sections were stained with 0.05% DAB at 25°C for 5 min. Immunohistological analysis was performed using a fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×1,000). The optical density (OD) of the positively stained area was quantified using Image-Pro Plus software (version 6; Media Cybernetics Inc.).

Culture of primary alveolar epithelial cells

Following sacrifice, mouse alveolar epithelial cells were separated from the lungs of mice in each group. First, 20 ml PBS was used to flush blood from the lung vasculature. Subsequently, a 1-2-mm section of lung tissue was excised and cut into 1-mm3 pieces on ice. To disperse and culture fresh tissue, tissues were cultured in DMEM (3 ml; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in 25 ml uncoated culture flasks with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 48-52 h. Tissue explants were removed and cells were maintained in DMEM (3 ml) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. After monolayers formed, cells were purified (1×105/ml) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Following culture for 3 days, cells were used for subsequent experiments. Alveolar epithelial cell morphology and proliferation were observed using an inverted light microscope (magnification, ×200) to determine cell viability and purity (data not shown). Alveolar epithelial cell structure was observed by transmission electron microscopy using a JEM-2000EX transmission electron microscope (magnification, ×17,000) according to the aforementioned protocol.

Experimental protocol in vitro

Cells were randomly divided into five groups (n=8 per group; Table I) as follows: i) Control group, cells were cultured in DMEM; ii) LPS group, cells treated with 1 µg/ml LPS for 4 h; iii) 1 µM GC group, cells pre-incubated with 1 µM GC for 24 h prior to LPS treatment; iv) 10 µM GC group, cells pre-incubated with 10 µM GC for 24 h prior to LPS treatment; and v) 100 µM GC group, cells pre-incubated with 100 µM GC for 24 h prior to LPS treatment.

Cell viability assay

MTT colorimetric assays were performed to assess alveolar epithelial cell viability. Following treatment with 1 µg/ml LPS for 4 h, cells were incubated with 5 mg/ml MTT at 37°C for 4 h. Subsequently, 100 µl DMSO was added for 15 min to dissolve the formazan crystals. OD was determined at a wavelength of 490 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The results are presented as a percentage of the OD in the control group.

Determination of cytokines

Blood samples and cell medium were collected separately. TNF-α (cat. no. 208348), IL-1β (cat. no. 197742) and IL-6 (cat. no. ab222503) levels were measured using mouse ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Western blotting

Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted from cells using a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay. Western blotting was performed as previously described with minor modifications (18). Proteins (50 µg) were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (20 V; 100 mA) overnight. Following blocking with 5% skimmed milk at 37°C for 4 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (all 1:1,000) targeted against: CD40 (cat. no. sc-59047), ICAM-1 (cat. no. sc-8439), VCAM-1 (cat. no. sc-13160), iNOS (cat. no. sc-7271), NF-κB p65 (cat. no. sc-166748), p-IκB-α (cat. no. sc-8404), IκB-α (cat. no. sc-1643) and IKK-β (cat. no. ab32135) at 4°C for 24 h. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. no. sc-2005; 1:800) at 25°C for 12 h. Protein bands were visualized using an ECL Plus kit and a Gel Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein expression was semi-quantified using Quantity One software (version 4.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Histone and β-actin were used as the loading controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Comparisons among groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

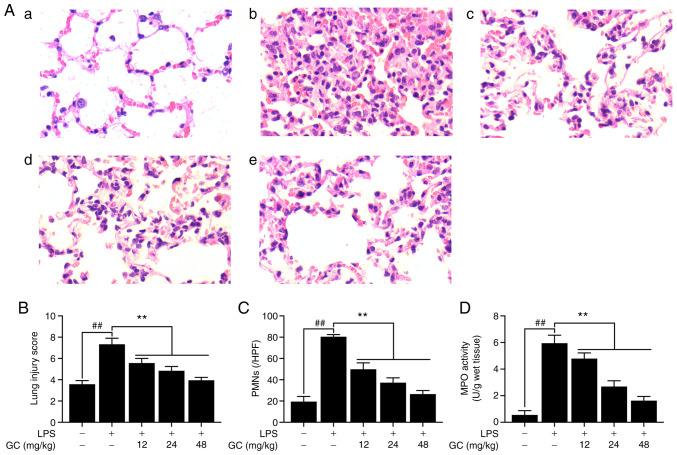

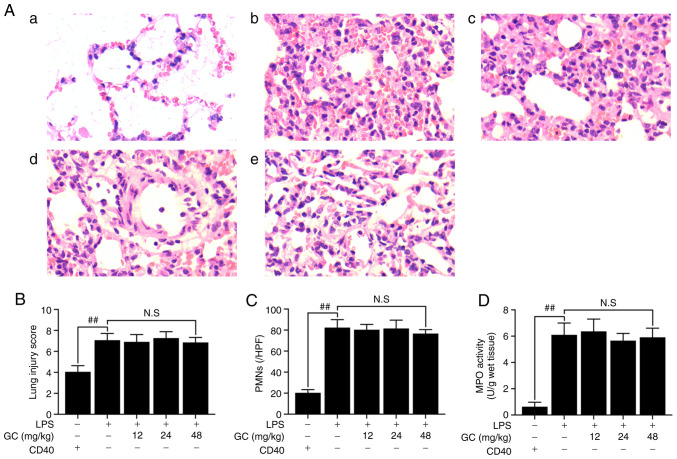

GC alleviates histopathological alterations, lung injury score, PMN infiltration and MPO activity in LPS-injured WT mice

The control group did not display lung injury, as indicated by simple columnar epithelium and cuboidal epithelium respiratory bronchioles, and normal wall structure in the pulmonary alveoli (Fig. 1A-a). By contrast, severe pathological alterations were observed in the LPS group, including cellular inflammatory infiltration, hemorrhage, pulmonary edema and thickening of the alveolar walls with disorganized alveolar structure (Fig. 1A-b). However, pretreatment with 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg GC notably ameliorated LPS-induced histopathological alterations (Fig. 1A-c-e). Moreover, pathological lung injury scores were significantly increased in the LPS group compared with the control group (Fig. 1B). However, 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg GC significantly reversed LPS-induced high lung injury scores. Additionally, prominent infiltration by leukocytes, primarily PMNs, in the interstitial and alveolar spaces of the lungs is one of the most important pathological hallmarks of ALI (21). In the present study, a significant increase in the number of PMNs was observed in the LPS group compared with the control group, suggesting increased inflammatory infiltration in the lungs (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, MPO activity was measured to evaluate the level of neutrophilic infiltration (Fig. 1D). MPO activity was very low (0.56±0.32 U/g protein) in the control group, but was significantly increased to 5.95±0.60 U/g protein in the LPS group. The results revealed that pretreatment with GC significantly inhibited LPS-induced MPO activity (12 mg/kg, 4.79±0.43 U/g protein; 24 mg/kg, 2.69±0.43 U/g protein; and 48 mg/kg, 1.63±0.31 U/g protein, respectively).

Figure 1.

Effects of GC on histopathological alterations, lung injury score, PMN count and MPO activity of lung tissue in LPS-injured wild-type mice. (A) Histopathological morphology was assessed by performing hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification, ×200) in the (a) control group, (b) LPS group, (c) 12 mg/kg GC group, (d) 24 mg/kg GC group and (e) 48 mg/kg GC group. Histological images were captured from three randomly selected fields of view. Effects of GC on (B) lung injury score, (C) PMN count and (D) MPO activity. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8). ##P<0.01 vs. control; **P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil; MPO, myeloperoxidase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; HPF, high-power field.

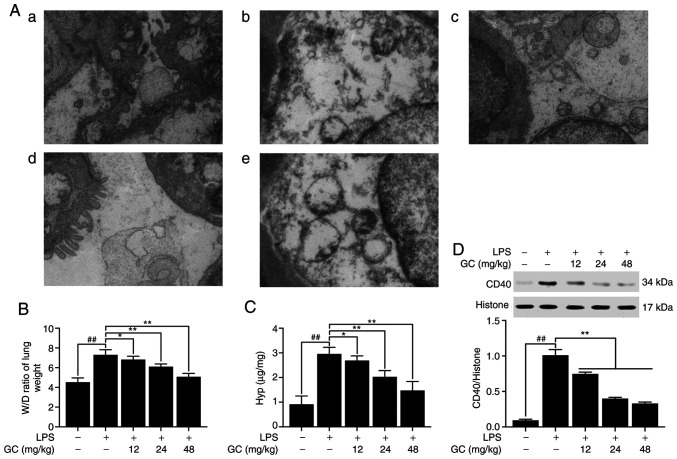

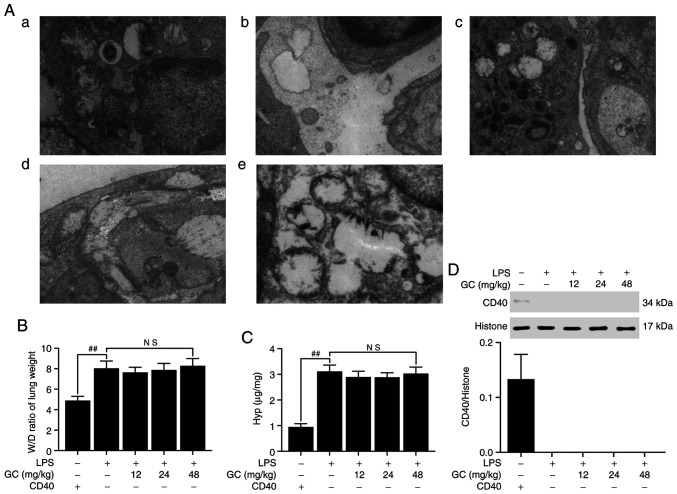

GC improves the ultrastructural characteristics of the lung and reduces the W/D weight ratio, Hyp activity and expression of CD40 in LPS-injured WT mice

The results demonstrated that there was no endothelial cell edema and the vascular basement membrane was intact in the control group (Fig. 2A-a). However, pathological alterations were obvious in the LPS group (Fig. 2A-b), including: i) Vacuolization, degeneration and necrosis in type I and II alveolar epithelial cells; ii) extensive shedding of microvilli and empty lamellar bodies; and iii) obvious PMN infiltration, vascular endothelial cell edema and basement membrane rupture in the alveolar spaces. Pretreatment with 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg GC notably reversed LPS-induced vascular endothelial cell damage and PMN infiltration (Fig. 2A-c-e). The lung W/D weight ratio was calculated to evaluate the degree of pulmonary edema in LPS-induced ALI. The W/D weight ratio in the LPS group was significantly higher compared with the control group (Fig. 2B). After pretreatment with 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg GC, lung permeability was significantly decreased and alveolar epithelial barrier damage was markedly reversed compared with the LPS group (Fig. 2B). Hyp activity in lung tissues reflects the proportion of tissue with collagen fibers (22). Hyp content of lung tissues in the control group was 0.91±0.34 µg/mg lung, which was significantly increased to 1.51±0.05 µg/mg lung in the LPS group (Fig. 2C). Hyp content in the 12, 24 and 48 mg/kg GC groups was significantly reduced to 2.11±0.13 (P<0.05), 2.70±0.15 (P<0.01) and 3.26±0.32 µg/mg lung (P<0.01), respectively, compared with the LPS group. Subsequently the expression of CD40 in lung tissue was measured. CD40 expression in the LPS group was significantly higher compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 2D). However, 12, 24 and 48 mg/kg GC significantly reduced LPS-induced CD40 expression levels (P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Effects of GC on ultrastructural characteristics, W/D weight ratio, Hyp activity and CD40 expression of lung tissue in LPS-injured wild-type mice. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy observation (magnification, ×17,000) of lung injury in the (a) control group, (b) LPS group, (c) 12 mg/kg GC group, (d) 24 mg/kg GC group and (e) 48 mg/kg GC group. Effects of GC on (B) W/D weight ratio, (C) Hyp activity and (D) CD40 expression. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8). ##P<0.01 vs. control; *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; W/D, wet-to-dry; Hyp, hydroxyproline; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

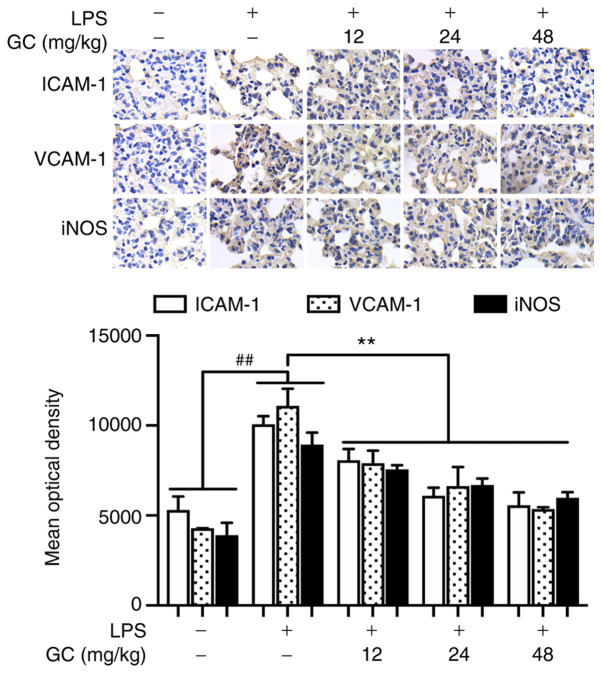

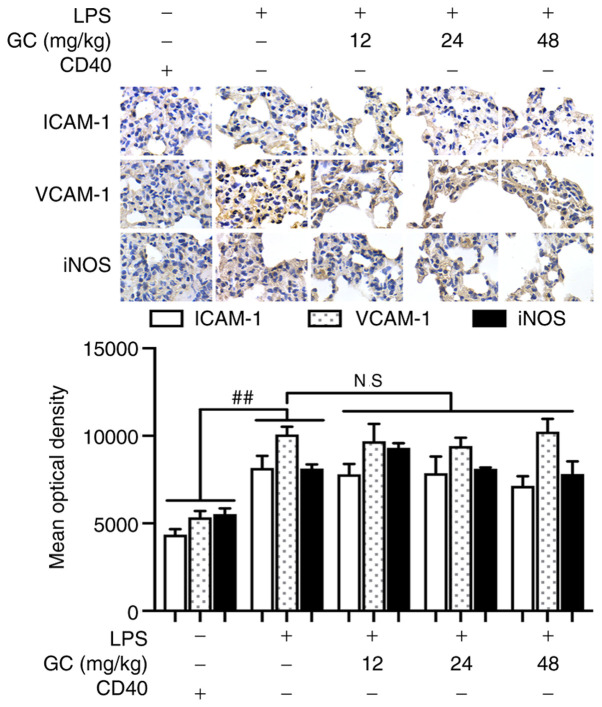

GC prevents ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS upregulation, and lowers inflammatory cytokine serum levels in LPS-injured WT mice

ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression levels in the LPS group were significantly increased by 1.90-, 2.58- and 2.29-fold, respectively, compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 3). Moreover, the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly increased by 4.73-, 6.57- and 138.08-fold, respectively, in the LPS group compared with the control group (P<0.01; Table II). However, 12, 24 and 48 mg/kg GC significantly downregulated ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression levels, and the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 compared with the LPS group (P<0.01).

Figure 3.

Effects of GC on ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression in LPS-injured wild-type mice. Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression in lung tissue. Magnification, ×1,000. ##P<0.01 vs. control; **P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Table II.

Effects of GC on serum inflammatory cytokines in LPS-injured wild-type mice.

| Group | TNF-α (pg/ml) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 10.74±3.24 | 3.20±0.59 | 0.57±0.25 |

| LPS | 50.82±6.55a | 20.99±2.48a | 78.93±5.85a |

| GC (12 mg/kg) | 36.70±6.09b | 14.51±0.65b | 55.10±4.30b |

| GC (24 mg/kg) | 31.84±4.13b | 9.98±1.35b | 41.54±3.92b |

| GC (48 mg/kg) | 17.18±5.08b | 7.48±1.63b | 30.41±6.85b |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8).

P<0.01 vs. control;

P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

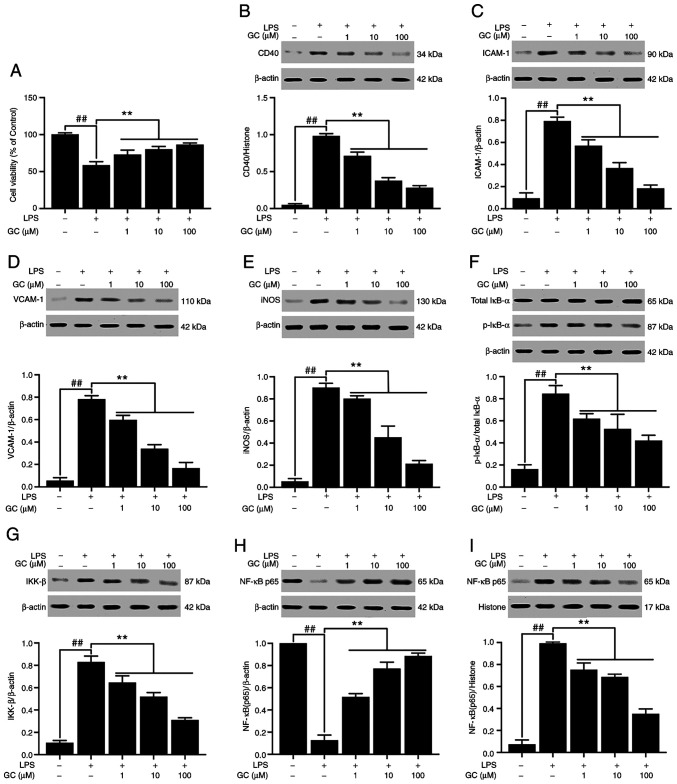

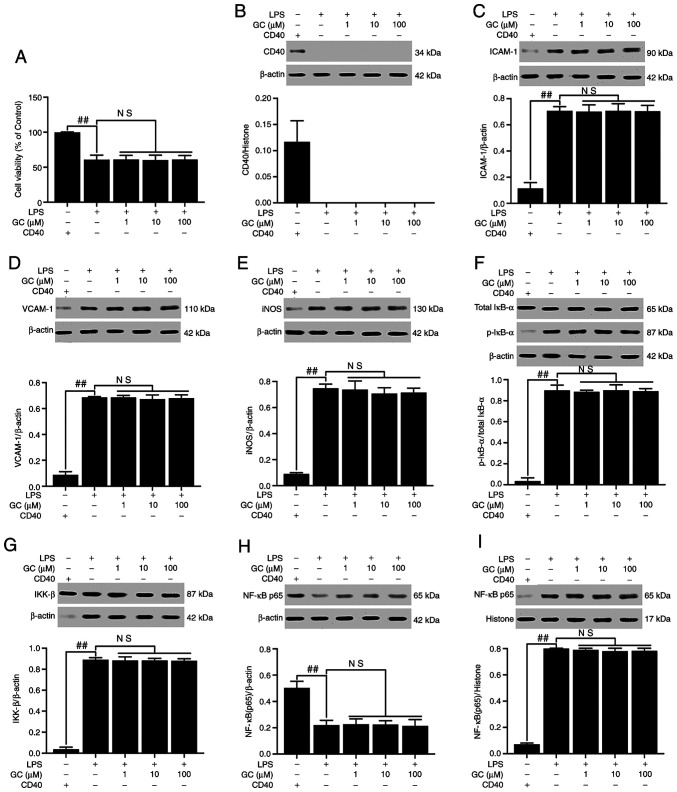

GC protects against cell injury, downregulates inflammatory factor expression and inhibits activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of WT mice

Compared with the control group, cell viability in the LPS group was significantly reduced to 58.71±4.78% (P<0.01; Fig. 4A). Treatment with 1, 10 or 100 µM GC significantly increased cell viability in LPS-treated alveolar epithelial cells (73.11±5.94, 80.04±3.84 and 86.44±2.29%, respectively; all P<0.01). CD40 expression was low in the control group, but LPS treatment significantly increased the expression of CD40 compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 4B). In addition, treatment with LPS significantly increased the expression levels of ICAM-1 (8.50-fold), VCAM-1 (13.82-fold) and iNOS (16.94-fold) compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 4C-E). Pretreatment with 1, 10 or 100 µM GC significantly decreased the expression levels of CD40 (by 27.46, 61.70 and 71.53%, respectively), ICAM-1 (by 28.15, 53.78 and 76.89%, respectively), VCAM-1 (by 23.83, 56.60 and 78.72%, respectively) and iNOS (by 11.07, 49.82 and 76.38%, respectively) compared with the LPS group (all P<0.01). No significant differences in the expression levels of total IκB-α were observed among the groups (Fig. 4F). However, compared with the control group, the expression levels of p-IκB-α were significantly increased by 5.02-fold in the LPS group (P<0.01). Compared with the control group, IKK-β expression was significantly increased by 7.78-fold in the LPS group (P<0.01), which was significantly reversed by pretreatment with 1, 10 or 100 µM GC (P<0.01; Fig. 4G). Moreover, the results demonstrated that the level of NF-κB p65 was relatively high in the cytoplasm but low the in nucleus in the control group (Fig. 4H and I). However, the translocation of p65 from the cytosol into the nucleus was significant in the LPS group compared with the control group (P<0.01). LPS-induced effects on NF-κB p65 were significantly reversed by pretreatment with 1, 10 or 100 µM GC (P<0.01). The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in the control group were 13.65±2.48, 34.85±2.30 and 50.28±7.87 pg/ml, respectively (Table III). The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in the LPS group were significantly increased to 89.61±7.04 pg/ml (6.56-fold), 709.67±56.24 pg/ml (20.36-fold) and 655.95±19.12 pg/ml (13.05-fold), respectively, compared with the control group (all P<0.01). Pretreatment with 1, 10 or 100 µM GC significantly decreased the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 compared with the LPS group (P<0.01).

Figure 4.

Effects of GC on cell viability and CD40, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, iNOS, p-IκB-α, IKK-β and NF-κB p65 expression levels in LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of wild-type mice. (A) Effects of GC on cell viability. Effects of GC on the protein expression levels of (B) CD40, (C) ICAM-1, (D) VCAM-1, (E) iNOS, (F) p-IκB-α/total IκB-α, (G) IKK-β, (H) cytoplasmic NF-κB p65 and (I) nuclear NF-κB p65. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01, vs. control; **P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; p, phosphorylated; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Table III.

Effects of GC on inflammatory cytokines levels in the cell medium of LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of wild-type mice.

| Group | TNF-α (pg/ml) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 13.65±2.48 | 34.85±2.30 | 50.28±7.87 |

| LPS | 89.61±7.04a | 709.67±56.24a | 655.95±19.12a |

| GC (1 µM) | 61.76±4.68b | 278.99±37.31b | 389.36±55.80b |

| GC (10 µM) | 40.56±6.32b | 232.06±35.37b | 292.07±42.87b |

| GC (100 µM) | 34.89±3.21b | 182.19±27.55b | 209.68±15.26b |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8).

P<0.01 vs. control;

P<0.01 vs. LPS. GC, Ginkgolide C; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

GC does not improve LPS-induced injury or inhibit the expression of inflammatory factors in LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice

To further verify the key roles of CD40 in the anti-ALI effects of GC, CD40-cKO mice were employed to establish an in vivo LPS-induced ALI mouse model. Compared with the control group, LPS treatment markedly aggravated histopathological alterations (Fig. 5A-2), lung injury scores (Fig. 5B), PMN infiltration (Fig. 5C) and MPO activity (Fig. 5D), destroyed the ultrastructural characteristics of lung tissue (Fig. 6A-2), elevated the W/D weight ratio (Fig. 6B) and Hyp activity (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the results presented in Fig. 6D demonstrated that CD40 gene was successfully and stably silenced in the lung tissues of mice, except in the control group. Moreover, LPS treatment significantly induced inflammatory reactions in CD40-cKO mice compared with the control group (Fig. 7 and Table IV). Notably, 12, 24 and 48 mg/kg GC failed to ameliorate LPS-induced alterations following CD40 gene silencing.

Figure 5.

Effects of GC on histopathological alterations, lung injury score, PMN count and MPO activity of lung tissue in LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice. (A) Histopathological morphology was assessed by performing hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification, ×200) in the (a) control group, (b) LPS group, (c) 12 mg/kg GC group, (d) 24 mg/kg GC group and (e) 48 mg/kg GC group. Histological images were captured from three randomly selected fields of view. Effects of GC on (B) lung injury score, (C) PMN count and (D) MPO activity. Wild-type mice were used as the control group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8). ##P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil; MPO, myeloperoxidase; cKO, conditional knockout; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; HPF, high-power field; NS, not significant.

Figure 6.

Effects of GC on ultrastructural characteristics, W/D weight ratio, Hyp activity and CD40 expression of lung tissue in LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice. (A) Representative transmission electron microscopy observation (magnification, ×17,000) of lung injury in the (a) control group, (b) LPS group, (c) 12 mg/kg GC group, (d) 24 mg/kg GC group and (e) 48 mg/kg GC group. Effects of GC on (B) W/D weight ratio, (C) Hyp activity and (D) CD40 expression. Wild-type mice were used as the control group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8). ##P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; W/D, wet-to-dry; Hyp, hydroxyproline; cKO, conditional knockout; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NS, not significant.

Figure 7.

Effects of GC on ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression in LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice. Immunohistochemistry was performed to evaluate ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS expression in lung tissue. Magnification, ×1,000. Wild-type mice were used as the control group. ##P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; cKO, conditional knockout; NS., not significant.

Table IV.

Effects of GC on serum inflammatory cytokines in LPS-injured CD40-cKO mice.

| Group | TNF-α (pg/ml) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 8.99±0.70 | 3.86±0.52 | 0.44±0.28 |

| LPS | 50.14±9.31a | 20.96±2.00a | 58.19±6.01a |

| GC (12 mg/kg) | 54.23±6.39 | 19.56±1.62 | 62.24±5.64 |

| GC (24 mg/kg) | 45.05±5.80 | 19.91±2.26 | 61.87±5.76 |

| GC (48 mg/kg) | 48.30±7.22 | 21.13±2.31 | 53.08±4.10 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8).

P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; cKO, conditional knockout.

GC exerts no effect on cell injury, expression of inflammatory factors or activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of CD40-cKO mice

CD40 was not expressed following CD40 gene conditional knockout, except in the control group (Fig. 8B). Following CD40 gene silencing, cell viability was significantly reduced, and the expression levels of CD40, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, iNOS and IKK-β, the phosphorylation of IκB-α, the translocation of NF-κB and the levels of inflammatory cytokines were significantly enhanced in the LPS group compared with the control group (P<0.01; Fig. 8 and Table V). As expected, the in vitro results were similar to the in vivo results; GC did not alter the viability or reverse injury in LPS-treated alveolar epithelial cells following CD40 gene silencing.

Figure 8.

Effects of GC on cell viability and CD40, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, iNOS, p-IκB-α, IKK-β and NF-κB p65 expression levels in LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of CD40-cKO mice. (A) Effects of GC on cell viability. Effects of GC on the protein expression levels of (B) CD40, (C) ICAM-1, (D) VCAM-1, (E) iNOS, (F) p-IκB-α/total IκB-α, (G) IKK-β, (H) cytoplasmic NF-κB p65 and (I) nuclear NF-κB p65. Alveolar epithelial cells from wild-type mice were used as the control group. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; p, phosphorylated; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; cKO, conditional knockout; NS, not significant.

Table V.

Effects of GC on inflammatory cytokine levels in the cell medium of LPS-injured alveolar epithelial cells of CD40-cKO mice.

| Group | TNF-α (pg/ml) | IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 13.84±2.55 | 30.38±6.04 | 60.02±14.72 |

| LPS | 85.56±9.57a | 709.65±72.75a | 741.05±104.58a |

| GC (1 µM) | 81.91±7.44 | 729.46±59.26 | 655.20±96.86 |

| GC (10 µM) | 82.22±8.90 | 680.37±69.73 | 616.25±88.45 |

| GC (100 µM) | 87.30±10.30 | 725.60±67.53 | 691.05±108.84 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=8).

P<0.01 vs. control. GC, Ginkgolide C; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; cKO, conditional knockout.

Discussion

LPS-induced excessive lung inflammation and destruction of the structure and function of alveolar epithelial cells are important pathological processes of ALI, which commonly result in significant morbidity or even death (23). Augmentation of inflammatory responses in the lung tissue stimulates the production of numerous cytotoxic substances, including various proinflammatory cytokines, ROS and granular enzymes, thereby affecting the development and severity of LPS-induced ALI (24). Therefore, inhibiting inflammation may serve as a promising and effective therapy for ALI. To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to suggest the key role of GC in the inflammatory pathological process of ALI via inhibition of the CD40/NF-κB signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro.

GC, a terpene lactone component of Ginkgo biloba leaves, displays a broad range of biological and pharmacological functions against various diseases, including memory loss and cognitive disorders, arrhythmias and ischemic heart disease, cancer, diabetes and thromboses (25,26). Our previous study focused on the cardioprotective effects of GC via suppression of CD40-NF-κB signaling pathway-activated inflammation (18); however, whether GC exerts a beneficial effect in ALI is not completely understood. To the best of our knowledge, the present study demonstrated for the first time that pretreatment with GC at 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg (per day for 7 days) markedly alleviated LPS-induced ALI, as evidenced by notable improvements in histopathological alterations, reductions in lung injury scores and restored lung ultrastructure. The significant alterations induced by GC may be partially explained by the fact that GC exerted a prominent protective effect against LPS-induced ALI.

It was previously reported that activated PMNs were a key event in the development of inflammation during ALI (27). These communications include paracrine cross talk between PMNs and alveolar epithelial cells. In the present study, LPS treatment results in widespread PMN infiltration, interstitial edema in the alveolar space and septum, notable thickening of the alveolar membrane and disruption of the normal alveolar structure. MPO, which is also considered as a specific marker of ALI and a risk factor for long-term mortality, is secreted by PMNs (28). The present study demonstrated that administration of 12, 24 or 48 mg/kg GC to WT mice significantly alleviated LPS-induced PMN infiltration and MPO activity. In addition, compared with the control group, significantly higher W/D weight ratios of the lung and Hyp content levels were observed in the LPS group, suggesting gradual aggravation of lung fluid leakage during the acute phase of lung injury. However, the W/D weight ratio and Hyp content were significantly decreased following treatment with 12, 24 and 48 mg/kg GC compared with the LPS group.

CD40 belongs to the TNFR superfamily and is universally expressed on the surface of resting and activated vascular endothelial cells and platelets (29). CD40L serves as a CD40 ligand and is primarily expressed on endothelial and epithelial cells, B cells, neutrophils and macrophages. The CD40-CD40L system serves a key role in various clinical settings, including inflammation, thrombosis, cancer and autoimmune diseases (30). More importantly, PMNs can express CD40, and CD40-CD40L binding rapidly primes PMNs, ultimately inducing PMN-mediated toxicity against alveolar epithelial cells (31). Although it is clear that CD40 induction of proinflammatory activity contributes to chronic inflammation in various clinical settings, the signaling pathway mediating its effects in ALI has only been partially described. In the present study, compared with the control group, CD40 expression in WT mice was significantly increased following LPS exposure, and GC pretreatment significantly downregulated CD40 expression in a concentration-dependent manner. Therefore, suppressing CD40 expression by GC may alleviate inflammation, thereby attenuating the severity of ALI.

CD40 signaling is closely associated with the non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway, followed by strongly triggered downstream signaling events (32,33). Under normal conditions, CD40-induced NF-κB activation involves the phosphorylation of IκB, which results in proteasome-mediated degradation. After the ubiquitylation and degradation of phosphorylated IκB, nuclear translocation of NF-κB is observed, which regulates the transcription of target genes (34). The present study demonstrated that compared with the control group, LPS exposure in alveolar epithelial cells from WT mice significantly increased the phosphorylation of IκB and translocation of NF-κB p65, indicating increased transcription of NF-κB and strict regulation of NF-κB signaling at the level of IκB phosphorylation. The IKK complex (IKK-α, -β and -γ) is activated by phosphorylation (primarily of IKK-α or IKK-β) within their activation loops, either by upstream kinases or via autophosphorylation. Then, phosphorylated IκB-α combines with the activated complex, causing its ubiquitin-mediated degradation and release of the NF-κB subunits (35,36). The present study demonstrated that IKK-β expression was significantly increased by LPS exposure compared with the control group. Moreover, the results indicated that IKK-β expression was significantly downregulation by GC in LPS-induced alveolar epithelial cells. Therefore, the CD40/IKK/NF-κB signaling pathway may serve as an inflammatory target in LPS-induced ALI.

A previous study indicated that activation of NF-κB occurs during the very early stages of ALI, and then sequentially regulates the expression of downstream inflammatory factors (37). Accordingly, immunostaining assays, ELISAs and western blotting were performed in the present study to verify whether LPS triggered a severe inflammatory reaction induced by NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. The results demonstrated that LPS aggravated ALI by promoting the production of proinflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) and the expression of inflammatory proteins (ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and iNOS) via an NF-κB-dependent signaling pathway, both in vivo and in vitro. However, pretreatment with GC effectively reversed LPS-induced effects. The results suggested that GC served a protective role against LPS-induced ALI via inhibiting inflammation induced by activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Based on the aforementioned results, it was inferred that CD40 served a key role in stimulating LPS-induced inflammation in ALI. Therefore, CD40-cKO mice and their alveolar epithelial cells were further examined to investigate this hypothesis in vivo and in vitro. The protective effects of GC against LPS-induced ALI were no longer observed following CD40 silencing, confirming that GC improved LPS-induced ALI by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway via CD40 (Fig. 9). Therefore, further elucidating how CD40 regulates LPS-induced inflammation may identify promising intervention targets for ALI.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of GC on LPS-induced inflammatory injury of alveolar epithelial cells. GC, Ginkgolide C; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ICAM-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Taken together, the results of the present study demonstrated that GC exerted a protective effect against LPS-induced ALI via inhibiting CD40/NF-κB signaling pathway-dependent inflammation. Therefore, GC may serve as an effective therapeutic agent for of ALI, and CD40 may be considered as a novel potential therapeutic target for ALI.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant nos. ZR2020QH358 and ZR2018PH037) and the Projects of Medical and Health Technology Development Program in Shandong Province (grant no. 2019WS492).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

RZ, NG, TG, GY, QW and BZ performed the experiments. RZ, NG and NH designed the present study. TG, GY, QW and BZ analyzed the data. RZ drafted and edited the manuscript. RZ and NH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (grant no. 2020-464).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mowery NT, Terzian WT, Nelson AC. Acute lung injury. Curr Probl Surg. 2020;57:100777. doi: 10.1016/j.cpsurg.2020.100777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuldanek SA, Kelher M, Silliman CC. Risk factors, management and prevention of transfusion-related acute lung injury: A comprehensive update. Expert Rev Hematol. 2019;12:773–785. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2019.1640599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semple JW, McVey MJ, Kim M, Rebetz J, Kuebler WM, Kapur R. Targeting transfusion-related acute lung injury: The journey from basic science to novel therapies. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e452–e458. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leite LFB, Máximo TA, Mosca T, Forte WCN. CD40 ligand deficiency. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2020;48:409–413. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.França TT, Barreiros LA, Al-Ramadi BK, Ochs HD, Cabral-Marques O, Condino-Neto A. CD40 ligand deficiency: Treatment strategies and novel therapeutic perspectives. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:529–540. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1573674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasgupta S, Dasgupta S, Bandyopadhyay M. Regulatory B cells in infection, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Cell Immunol. 2020;352:104076. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subauste CS. The CD40-ATP-P2X7 receptor pathway: Cell to cell cross-talk to promote inflammation and programmed cell death of endothelial cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2958. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujihara C, Kanai Y, Masumoto R, Kitagaki J, Matsumoto M, Yamada S, Kajikawa T, Murakami S. Fibroblast growth factor-2 inhibits CD40-mediated periodontal inflammation. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:7149–7160. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seigner J, Basilio J, Resch U, de Martin R. CD40L and TNF both activate the classical NF-κB pathway, which is not required for the CD40L induced alternative pathway in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495:1389–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.11.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolaver RA, Wang X, Dollin Y, Xie P, Wang JH, Chen Z. TRAF2 deficiency in B cells impairs CD40-Induced isotype switching that can be rescued by restoring NF-κB1 activation. J Immunol. 2018;201:3421–3430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulero MC, Huxford T, Ghosh G. NF-kappaB, IkappaB, and IKK: Integral components of immune system signaling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1172:207–226. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-9367-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand JK, Baldwin AS. Targeting IKK and NF-κB for therapy. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2017;107:77–115. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pordanjani SM, Hosseinimehr SJ. The role of NF-κB inhibitors in cell response to radiation. Curr Med Chem. 2016;23:3951–3963. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160824162718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott O, Roifman CM. NF-κB pathway and the goldilocks principle: Lessons from human disorders of immunity and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1688–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellner M, Noonepalle S, Lu Q, Srivastava A, Zemskov E, Black SM. ROS signaling in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;967:105–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-63245-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward PA, Fattahi F, Bosmann M. New insights into molecular mechanisms of immune complex-induced injury in lung. Front Immunol. 2016;7:86. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang J, Wang Z, Wang P, Wang M. Extraction, structure and bioactivities of the polysaccharides from Ginkgo biloba: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;62:1897–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Han D, Li Z, Shen C, Zhang Y, Li J, Yan G, Li S, Hu B, Li J, Liu P. Ginkgolide C alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammatory injury via inhibition of CD40-NF-κB pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:109. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su X, Wang L, Song Y, Bai C. Inhibition of inflammatory responses by ambroxol, a mucolytic agent, in a murine model of acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuigan RM, Mullenix P, Norlund LL, Ward D, Walts M, Azarow K. Acute lung injury using oleic acid in the laboratory rat: Establishment of a working model and evidence against free radicals in the acute phase. Curr Surg. 2003;60:412–417. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7944(02)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chopra M, Reuben JS, Sharma AC. Acute lung injury: Apoptosis and signaling mechanisms. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:361–371. doi: 10.3181/0811-MR-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao F, Shi D, Li T, Li L, Zhao M. Silymarin attenuates paraquat-induced lung injury via Nrf2-mediated pathway in vivo and in vitro. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;42:988–998. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toumpanakis D, Vassilakopoulou V, Sigala I, Zacharatos P, Vraila I, Karavana V, Theocharis S, Vassilakopoulos T. The role of Src and ERK1/2 kinases in inspiratory resistive breathing induced acute lung injury and inflammation. Respir Res. 2017;18:209. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0694-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouda MM, Bhandary YP. Acute lung injury: IL-17A-mediated inflammatory pathway and its regulation by curcumin. Inflammation. 2019;42:1160–1169. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-01010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omidkhoda SF, Razavi BM, Hosseinzadeh H. Protective effects of Ginkgo biloba L. against natural toxins, chemical toxicities, and radiation: A comprehensive review. Phytother Res. 2019;33:2821–2840. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubey AK, Shankar PR, Upadhyaya D, Deshpande VY. Ginkgo biloba-an appraisal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2004;2:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boxio R, Wartelle J, Nawrocki-Raby B, Lagrange B, Malleret L, Hirche T, Taggart C, Pacheco Y, Devouassoux G, Bentaher A. Neutrophil elastase cleaves epithelial cadherin in acutely injured lung epithelium. Respir Res. 2016;17:129. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0449-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao H, Chen H, Xiaoyin M, Yang G, Hu Y, Xie K, Yu Y. Autophagy activation improves lung injury and inflammation in sepsis. Inflammation. 2019;42:426–439. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-00952-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda H, Mori M, Umehara K, Furihata T, Uchida T, Uzawa A, Kuwabara S. Soluble CD40 ligand disrupts the blood-brain barrier and exacerbates inflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2018;316:117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takada YK, Yu J, Shimoda M, Takada Y. Integrin binding to the trimeric interface of CD40L plays a critical role in CD40/CD40L signaling. J Immunol. 2019;203:1383–1391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu ZL, Hu J, Xiao XF, Peng Y, Zhao SP, Xiao XZ, Yang MS. The CD40 rs1883832 polymorphism affects sepsis susceptibility and sCD40L levels. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:7497314. doi: 10.1155/2018/7497314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishop GA, Stunz LL, Hostager BS. TRAF3 as a multifaceted regulator of B lymphocyte survival and activation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2161. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu N, Lambert S, Bornstein J, Nair RP, Enerbäck C, Elder JT. The Act1 D10N missense variant impairs CD40 signaling in human B-cells. Genes Immun. 2019;20:23–31. doi: 10.1038/s41435-017-0007-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan WZ, Du J, Zhang LY, Ma JH. The roles of NF-κB in the development of lung injury after one-lung ventilation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:7414–7422. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201811_16281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulivi V, Giannoni P, Gentili C, Cancedda R, Descalzi F. p38/NF-κB-dependent expression of COX-2 during differentiation and inflammatory response of chondrocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1393–1406. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yin HC, Liu XY, Liu PM, Zhang H, Liang P, Wang ZL, She MP. Effect of mm-LDL on NF-κB activation in endothelial cell. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2001;23:312–316. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asaad NY, Sadek GS. Pulmonary cryptosporidiosis: Role of COX2 and NF-κB. APMIS. 2006;114:682–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.