Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to identify the factors influencing the delay in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA negative conversion.

Methods

A cohort study was conducted that included patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) admitted to the Tunisian national containment center. Follow-up consisted of a weekly RT-PCR test. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine independent predictors associated with negative RNA conversion.

Results

Among the 264 patients included, the median duration of viral clearance was 20 days (interquartile range (IQR) 17–32 days). The shortest duration was 9 days and the longest was 58 days. Factors associated with negative conversion of viral RNA were symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and shortness of breath (hazard ratio (HR) 0.600, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.401–0.897) and face mask use when exposed to COVID-19 cases (HR 2.006, 95% CI 1.247–3.228). The median time to RNA viral conversion was 18 days (IQR 16–21 days) when using masks versus 23 days (IQR 17–36 days) without wearing masks, and 24 days (IQR 18–36 days) for symptomatic patients versus 20 days (IQR 16–30 days) for asymptomatic patients.

Conclusions

The results of this study revealed that during SARS-CoV-2 infection, having symptoms delayed viral clearance, while wearing masks accelerated this conversion. These factors should be taken into consideration for the strategy of isolating infected patients.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Viral shedding, Negative conversion, Tunisia

Introduction

Cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology were first reported from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in December 2019 (Shi et al., 2020). In February 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) named this emerging disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the agent responsible was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Lai et al., 2020).

The current COVID-19 pandemic has been spreading worldwide at an accelerated rate. According to the WHO, as of February 14, 2021, approximately 108 153 741 confirmed cases had been reported globally with more than 2 381 295 deaths across 216 countries (WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, n.d.)

Tunisia reached a turning point on March 22, 2020, and general health containment was started. The strategy was based on testing, tracing, and isolation in accordance with the WHO guidelines. The government and health ministry of Tunisia have since launched a series of measures to screen, quarantine, diagnose, treat, and monitor suspected patients and their close contacts. The lifting of the compulsory confinement of SARS-CoV-2 carrying subjects in a dedicated center was announced on July 14, 2020.

Tunisia is now experiencing a second wave of the pandemic and COVID-19 is spreading exponentially. Up until February 14, 2021 there had been 222 504 confirmed cases of COVID-19 with 7508 deaths (‘Tunisia’ WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, n.d.).

Since the identification of the first cases of COVID-19, numerous studies focusing on the epidemiological, clinical, and radiological characteristics of infected patients and on treatment strategies have been reported in Tunisia. However, data regarding the potential factors associated with the delay in RNA negative conversion of patients with COVID-19 are limited (Hu et al., 2020).

A patient’s infectivity is determined by the presence of the virus in body fluids, secretions, and excreta (Ling et al., 2020). All patients with positive viral RNA detection need to be isolated, and isolated patients can only be discharged after the relief of symptoms and two successive negative viral nucleic acid results for respiratory specimens (Qi et al., 2020). The predictors of persistence and clearance of viral RNA in different specimens from COVID-19 patients remain unclear. Knowledge has been accumulating on this topic for hospitalized and critically ill patients; however, information about patients with disease of mild severity is scarce (Ling et al., 2020, Qi et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020), and most COVID-19 patients have mild clinical symptoms (Qi et al., 2020). Data on viral RNA shedding among patients with mild COVID-19 are of paramount importance to prevent transmission of this disease. Indeed, identifying people likely to be slow shedders is crucial to prolong their isolation, once infected, and avoid the virus spread, especially as it is not possible to confirm negative conversion by two reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) tests due to the international shortage and increasing numbers of cases. Thus, understanding factors associated with prolonged viral clearance among asymptomatic/mild cases is important to tailor prevention strategies.

The aim of this study was to identify the potential predictors of RNA negative conversion delay among asymptomatic and mild symptoms COVID-19 patients.

Patients and methods

Study design

A cohort study was conducted that included patients with confirmed COVID-19 confined in the national COVID-19 center from March to July 2020.

Setting

The national COVID-19 center (a hotel for COVID-19 patients) was located in Monastir governorate. This community facility was designated for the isolation of patients with or without symptoms of COVID-19 in Tunisia (from the 24 Tunisian governorates). The Tunisian government allocated individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 to dedicated isolation facilities and the remaining individuals with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 to hospitals. This allocation of individuals positive for COVID-19 was continued from March to July 29, 2020. Exposure to isolation and follow-up for each case covered the period from admission to the announcement of recovery. Data were collected prospectively on a daily basis.

Participants

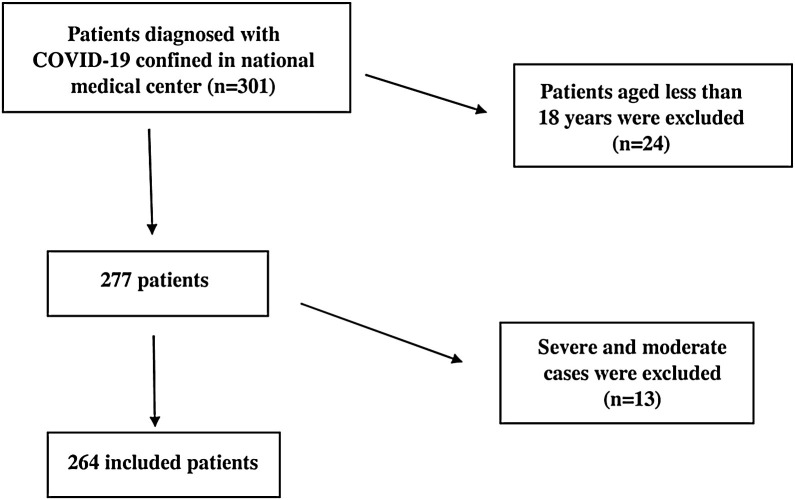

Patients over 18 years of age with positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA from nasopharyngeal/throat swabs by real-time RT-PCR were included. All cases progressing to a moderate or severe form requiring hospitalization were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Methods of participant selection

Cases were identified through the testing of individuals suspected to have COVID-19 and through contact-tracing involving close contacts of confirmed COVID-19 cases, tested within 24–48 h.

Methods of follow-up

The follow-up consisted of weekly RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 to check for viral clearance. Patients also had to have been symptom-free for at least 3 days before being considered for discharge. If the RT-PCR test result was positive, a swab was repeated after at least 7 days. If the RT-PCR test result was negative, a second swab was performed after at least 48 h to confirm viral clearance. Those individuals with two consecutive negative RT-PCR test results within 24 h were then considered virus-free and were discharged from the containment center.

Variables and data collection

Outcome

Conversion of viral RNA was defined as the period between the day of the first RT-PCR positive result and the day of the second successive negative RNA SARS-CoV-2 test result, as proposed in previous studies dealing with a similar topic (Hu et al., 2020, Gao and Li, 2020). A SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by testing respiratory specimens based on RT-PCR assays from different agreed institutions, including the University of Monastir laboratory.

Exposure

Patients were required to stay in their hotel rooms during the isolation period. Their meals were served in their rooms. Telephone medical assistance was provided on a daily basis by the Monastir Preventive Medicine Department team. A toll-free number was given to each patient for any emergency to be resolved by the containment center staff.

Predictors and diagnostic criteria

Initially, demographic and clinical characteristics were collected. A daily telephone call was made to collect information on the clinical course and provide information on compliance with isolation measures. Patients were also asked if they had worn a mask when exposed to the index case and when they had contracted the virus, and whether they lived in a single room or not. The announcement of recovery was made after the second negative RT-PCR, reported by the laboratory within 24–48 h. After recovery, the patients were asked about their level of compliance in respecting hygiene and isolation measures.

The SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by testing respiratory specimens based on RT-PCR assays from different institutions, including the local laboratory of Fattouma Bourguiba University Hospital. Asymptomatic cases were defined as SARS-CoV-2-positive individuals without clinical signs. A symptomatic case was defined as any SARS-CoV-2-positive individual by RT-PCR with at least one symptom of COVID-19 since the admission, including but not limited to cough, fever, headache, muscle pain, shortness of breath, anosmia, and ageusia. Mild cases included patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 with upper airway symptoms and fever, myalgia and cough, with a normal pulmonary clinical examination. Patients were discharged based on respiratory samples consecutively negative for RNA on testing, with an interval of at least 1 day.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as the mean and standard deviation, or as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described as the frequency and percentage. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare the differences between two groups for quantitative variables.

In this study, negative conversion of viral RNA during the communicable period, as time-to-event data, was the outcome measure; this was illustrated with Kaplan–Meier curves. In order to detect the independent factors influencing the duration of RNA negative conversion, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed.

For demographic, epidemiological, clinical, and virological variables, the log-rank test was first conducted.

A multivariate Cox regression model was then performed with the significant factors selected by univariate analysis (P-value <0.2) to determine the independent predictors of RNA negative conversion.

The association between independent factors and negative conversion was quantified by hazard ratio (HR), reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI). As negative conversion of viral RNA is a favorable event, an HR value >1 would indicate accelerated virological clearance, whereas an HR < 1 would mean that the independent predictor would delay negative conversion.

A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 264 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 staying in the Monastir containment center were identified. Imported cases accounted for 30.6%. The median age of the patients was 42.5 years (IQR 30–55 years). Of the 264 confirmed cases, 133 were female (50.4%) and 131 were male (49.6%). The mean body mass index (BMI) of these patients was 26.3 ± 4.7 kg/m2.

Nearly 31.7% of patients had at least one underlying disease such as diabetes (16.8%; n = 41), hypertension (15.6%; n = 38), and asthma (6.2%; n = 15). Almost 10.5% were current smoker. Symptoms such as anosmia, dry cough, and fatigue were reported by 34.4% (n = 75) of cases.

Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 264 patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Characteristics | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 133 | 50.4 |

| Male | 131 | 49.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≥60 | 43 | 16.4 |

| <60 | 219 | 83.6 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Smoker | 22 | 10.5 |

| Hypertension | 38 | 15.6 |

| Diabetes | 41 | 16.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 | 2.1 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 22 | 15.4 |

| Asthma | 15 | 6.2 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Yes | 75 | 34.4 |

| No | 143 | 65.6 |

| Isolated room | ||

| Yes | 168 | 90.3 |

| No | 18 | 9.7 |

| Contact with face mask | ||

| Yes | 25 | 19.5 |

| No | 103 | 80.5 |

SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; BMI, body mass index.

Duration of viral RNA conversion

The median duration of viral conversion in this study was 20 days (IQR 17–32 days). The shortest duration was 9 days and the longest was 58 days. The patient with the shortest duration to RNA viral clearance was a 43-year-old male with no comorbidities. Regarding the longest duration of 58 days, the patient concerned was a 62-year-old male with hypertension. No symptoms were reported during RT-PCR positivity in either of these cases.

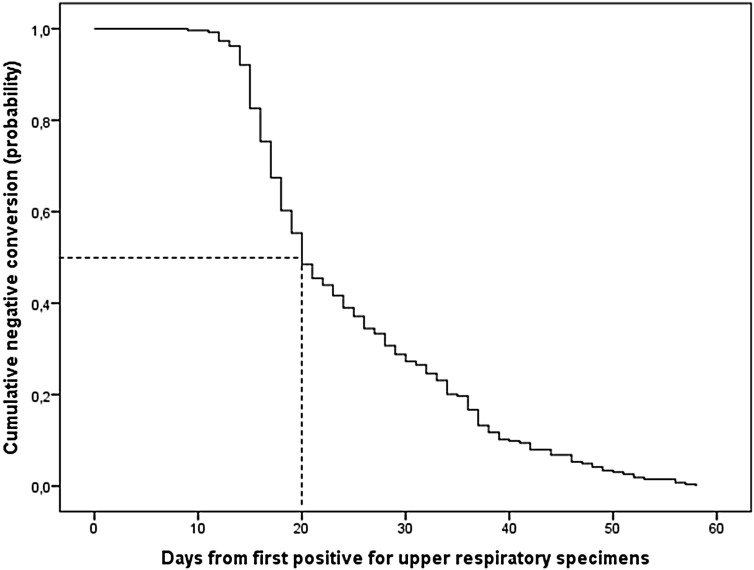

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve representing the overall negative conversion of viral RNA in COVID-19 patients is illustrated in Figure 2. The median time to viral clearance by age category is reported in Table 2 .

Figure 2.

Overall negative conversion curve for COVID-19 patients.

Table 2.

Median time to viral clearance according to age category, calculated using the Kaplan–Meier survival estimator.

| Age categories (years) | Total (%) (N = 264) | Time to viral clearance from first positive swab (days) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR (25%–75%) | ||

| <30 | 60 (22.7) | 21 | 18–34 |

| 30–40 | 61(23.1) | 18 | 16–27 |

| 40–50 | 48 (18.2) | 23 | 16–34 |

| 50–60 | 52 (19.7) | 20 | 16–34 |

| ≥60 | 43 (16.3) | 20 | 17–33 |

IQR, interquartile range. Log-rank test P-value = 0.120.

Ten patients (3.8%) had consecutive negative RT-PCR within 14 days, 136 patients (51.5 %) within 21 days, and 176 patients (66.7%) within 28 days.

Factors related to SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative conversion duration

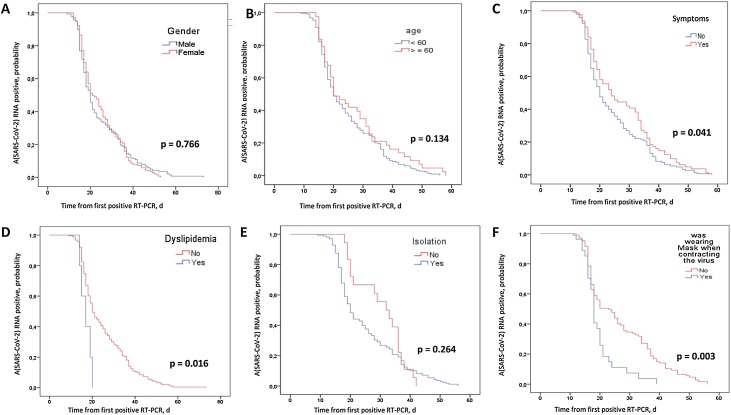

The effect of each factor on negative conversion of COVID-19 patients was evaluated by log-rank test (Figure 3). It was found that SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance was significantly delayed in symptomatic patients (log-rank test, P = 0.041; Figure 3C). The median duration was 24 days (IQR 18–36 days) for symptomatic cases and 20 days (IQR 16–30 days) for asymptomatic cases. Table 3 demonstrates the median time to SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral clearance according to the clinical characteristics of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases.

Figure 3.

Negative conversion curves for COVID-19 patients according to predictors, by day (d) after first positive RT-PCR: (A) sex; (B) age; (C) symptoms; (D) dyslipidemia; (E) isolated room; (F) was wearing masks when contracted the virus.

Table 3.

Median time to SARS-CoV-2 RNA viral clearance according to clinical characteristics of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases.

| Characteristics | Symptomatic cases | Asymptomatic cases | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 75) | (n = 143) | ||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Crude analysis | |||

| 24 (18–36) | 20 (16–30) | 0.017 | |

| Stratified analysis | |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 21 (17–36) | 20 (16–30) | 0.467 |

| Male | 31 (20–35) | 20 (16–30) | 0.009 |

| P-value | 0.15 | 0.45 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| <60 | 24 (18–36) | 20 (16–30) | 0.016 |

| ≥60 | 20 (17–36) | 21 (16–31) | 0.674 |

| P-value | 0.86 | 0.47 | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 23 (17–36) | 20 (16–32) | 0.184 |

| Yes | 27 (21–38) | 18 (17–21) | 0.138 |

| P-value | 0.52 | 0.61 | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 24 (18–36) | 20 (17–30) | 0.040 |

| Yes | 25 (17–40) | 20 (15–28) | 0.180 |

| P-value | 0.86 | 0.27 | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 25 (18–36) | 20 (16–30) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 18 (15–30) | 20 (15–30) | 0.723 |

| P-value | 0.12 | 0.76 | |

| Asthma | |||

| No | 24 (18–36) | 20 (16–30) | 0.012 |

| Yes | 23 (15–33) | 16 (15–33) | 0.710 |

| P-value | 0.38 | 0.42 | |

| Obesity | |||

| BMI <30 | 25 (19–37) | 20 (17–29) | 0.043 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 19 (14–37) | 17 (16–23) | 0.508 |

| P-value | 0.05 | 0.21 | |

| Isolated room | |||

| No | 31 (20–36) | 36.5 (29–39) | 0.147 |

| Yes | 24 (17–37) | 20 (17–30) | 0.101 |

| P-value | 0.47 | 0.01 | |

| Contact with masks | |||

| No | 29 (18–40) | 19 (16–30) | 0.007 |

| Yes | 19 (16–23) | 17 (16–19) | 0.198 |

| P-value | 0.02 | 0.24 | |

SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index (kg/m2).

According to the study findings, viral RNA negative conversion was significantly faster in patients with dyslipidemia (log-rank test, P = 0.016; Figure 2D) and in patients who were wearing face masks when they contracted the virus (log-rank test, P = 0.003; Figure 2F). The median time to RNA viral conversion was 18 days (IQR 16–21 days) for patients using face masks versus 23 days (IQR 17–36 days) for patients who did not wear one.

There was no significant difference in the duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative conversion according to sex (Figure 2A), age over 60 years (Figure 2B), current smoking, comorbidities, and isolation in a single room (Figure 2E).

Table 4 summarizes the results of the univariate and multivariate analyses.

Table 4.

Risk factors associated with prolonged negative conversion of viral RNA.

| Univariate analysis Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis Adjusted HR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | Ref. | |||||

| Male | 0.965 | (0.756–1.232) | 0.776 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <60 | Ref. | |||||

| ≥60 | 0.783 | (0.560–1.095) | 0.153 | 1.480 | (0.834–2.624) | 0.180 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1.237 | (0.792–1.931) | 0.349 | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 0.949 | (0.664–1.355) | 0.772 | |||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1.235 | (0.882–1.730) | 0.220 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 2.742 | (1.119–6.717) | 0.027 | 1.924 | (0.249–14.862) | 0.530 |

| Asthma | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1.157 | (0.685–1.954) | 0.586 | |||

| Symptoms | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 0.756 | (0.570–1.002) | 0.051 | 0.600 | (0.401–0.897) | 0.013 |

| Obesity | ||||||

| BMI <30 | Ref. | |||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.286 | (0.807–2.051) | 0.290 | |||

| Isolated room | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1.304 | (0.799–2.128) | 0.288 | |||

| Contact with masks | ||||||

| No | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1.924 | (1.218–3.039) | 0.005 | 2.006 | (1.247–3.228) | 0.004 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index (kg/m2).

Multivariate Cox regression was performed with the significant factors selected by univariate analysis. The presence of symptoms (HR 0.600, 95% CI 0.401–0.897) and the use of face masks when exposed to people diagnosed with COVID-19 (HR 2.006, 95% CI 1.247–3.228) were independently associated with negative conversion of viral RNA, suggesting that the presence of symptoms during SARS-CoV-2 infection delays virological clearance and wearing masks reduces the duration in COVID-19 patients.

Discussion

Key results

Until now, there have been few studies on the predictors of the time to negative conversion of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Viral shedding has been related to infectivity and transmissibility in influenza virus infections, and an understanding of this is crucial for the implementation of prevention strategies (Ryoo et al., 2013). Therefore, it is important to determine the duration of viral shedding and related factors in patients with COVID-19 (Qi et al., 2020). The present study showed face mask wearing and having symptoms to be associated with the time to RNA conversion. The median time to RNA viral conversion was 18 days (IQR 16–21 days) for those who wore a mask when in contact with the index case versus 23 days (IQR 17–36 days) for those who did not wear a mask, and was 24 days (IQR 18–36 days) for symptomatic patients versus 20 days (IQR 16–30 days) for asymptomatic individuals.

Interpretation

The median time to viral conversion observed in the study cohort was 20 days (IQR 17–32 days) from the first positive RT-PCR test, similar to the results of the study by Zhou et al. (Zhou et al., 2020). Other studies have demonstrated a shorter median duration of viral shedding of 9.5 days (IQR 6.0–11.0 days) and 14 days (IQR 10–18 days) (Hu et al., 2020, Ling et al., 2020). Another study in Italy reported a longer median duration of viral shedding of 31 days (IQR 24–41 days) (Mancuso et al., 2020). The discrepancies might be attributed to the heterogeneity of patients and disease severity in these studies. Differences may also have resulted from the different starting points for RNA viral clearance in previous reports. In the present study, the definition was in line with that used in other high-quality studies, as mentioned in the Methods section (Hu et al., 2020, Gao and Li, 2020).

The results of this study showed that sex was not related to the duration of viral shedding. However, a previous study showed that male sex was a predictor of prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance (Xu et al., 2020). The mechanism of sex-related differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection is unclear. It might be related to sex hormones, which appear to influence the immune system. Females are reported to produce more cellular and humoral immune reactions, and so are more resistant to certain infections (Bouman et al., 2005).

Smoking was found not to be a predictor of prolonged viral shedding in this study, in line with results reported in a previous study (Xu et al., 2020). A meta-analysis based on 19 peer-reviewed papers, demonstrated a significant association between smoking and the progression of COVID-19 (Patanavanich and Glantz, 2020). Indeed, the adverse effect of smoking on pulmonary immune function is a risk factor for serious outcomes among infected people (Bauer et al., 2013). Health care providers should take active measures to slow the trend in smoking, and public health campaigns should underline the importance of smoking cessation during the pandemic.

Furthermore, the current study does not support diabetes and hypertension as predisposing factors for late SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance, similar to previous studies (Hu et al., 2020).

This study showed no increase in time to viral clearance with increasing age. Older age (over 60 years) was not found to be an independent predictive factor of prolonged viral RNA shedding. Similarly, a recent systematic review reported no significant age-related differences in the duration of both respiratory tract swab positivity and fecal sample positivity (Morone et al., 2020). However, it was demonstrated that older age was correlated to a later RT-PCR conversion (Hu et al., 2020, Mori et al., 2020). COVID-19 is more likely to infect older patients due to their weaker immune system (Liu et al., 2020a). Indeed, T-cell numbers and functions are highly affected by aging, leading to less controlled viral replication and host inflammatory responses (Goronzy et al., 2007). Moreover, age-related comorbidities may result in prolonged viral shedding among the elderly (Liu et al., 2020a). However, no significant difference was noted concerning comorbidities in the current study. The effect of age on RNA viral clearance in patients with COVID-19 still needs further investigation.

Interestingly, not wearing masks and having symptoms were associated with prolonged viral RNA clearance. Virological and epidemiological data have led to the hypothesis that face mask wearing may reduce the severity among infected people (Gandhi and Rutherford, 2020). In an outbreak on a closed Argentinian cruise ship, the rate of asymptomatic infection among passengers wearing surgical and N95 masks was 81% compared with 20% in those who did not wear a mask (Gandhi et al., 2020).

Wearing a mask could reduce the virus dose received, leading to less severe manifestations of COVID-19. Long-lasting negative RNA conversion might also be proportionate to the viral SARS-CoV-2 inoculum received, explaining the association between facial mask wearing and viral shedding in the study findings. This indicates another possible advantage of population-wide mask-wearing for pandemic control regarding the viral inoculum, attenuating severe disease and accelerating SARS-CoV-2 recovery. Enforced population mask-wearing is the key strategy now as we await the results of vaccine trials. Therefore, strategic guidance should be established and a sufficient supply of masks should be guaranteed.

Developing symptoms was a predictor of prolonged negative RNA conversion. Mild cases were found to have early clearance in comparison to severe cases, in which the mean viral load was 60 times higher than that in mild cases, suggesting that higher viral loads might be associated with a longer viral shedding period (Liu et al., 2020b). However, and unexpectedly, previous studies have reported that the viral load in asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 patients was as high as that in symptomatic patients (Lee et al., 2020, Zou et al., 2020). The present study data indicate that patients with symptoms tend to have a prolonged viral clearance, and this might be a useful marker for assessing the disease prognosis.

This study has some limitations. First, RNA was only analyzed in nasopharyngeal and not in patient excretions such as urine and feces. However, previous studies have shown that viral loads in patient excretions might be higher than those in respiratory specimens (Li et al., n.d.). Second, this study reports only qualitative results of RNA detection, but persistent positivity for SARS-CoV-2 RNA does not necessarily indicate persistent shedding of live virus. To date, it is unknown how the shedding of viral RNA correlates with the shedding of infectious virus and this needs further studies.

Implications for practice and generalizability

The study results highlight the point that asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 patients will test positive for SARS-CoV-2 when released according to the latest WHO recommendation (Criteria for Releasing COVID-19 Patients from Isolation, n.d.). The study data indicate that asymptomatic patients recover more quickly than symptomatic patients. Future studies with viral load data are recommended to specify the containment periods for both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases.

Finally, and since participants who were wearing masks at the time they contracted the virus had a shorter duration of viral clearance, masks should be encouraged not only to prevent the spread of the epidemic, but also to reduce the viral dose received when contracting the virus and to have rapid viral clearance after infection.

Conclusions

This study with a relatively large sample size is novel in focusing on the duration of RNA viral clearance and related factors in patients with COVID-19 in Tunisia. This study demonstrated that the presence of symptoms and not wearing face masks were associated with delayed negative RNA conversion in patients with mild COVID-19. The study results have relevant public health implications. It is hoped that these predictors could provide clues for the early identification of cases with prolonged viral shedding, in order avoid virus spread.

Funding

There was no external funding for this article

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Monastir approved the protocol of this study. To maintain the principle of confidentiality, the data used were anonymized.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

We do not have any conflicts of interest associated with this publication. There was no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cyrine Bennasrallah: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft. Imen Zemni: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Wafa Dhouib: Validation. Haythem Sriha: Data curation. Nourhene Mezhoud: Data curation. Samar Bouslama: Data curation. Wael Taboubi: Data curation. Meriem Oumaima Beji: Data curation. Meriem Kacem: Validation. Hela Abroug: Validation. Manel Ben Fredj: Validation. Chawki Loussaief: Supervision, Validation. Asma Sriha Belguith: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the following individuals and all of the staff of the national COVID-19 containment center for their help in data collection: Manel ben Belgacem, Mondher Rebhi, Kmar Mrad, Manel Mantassar, Mohamed Hammadi, Karawen Sakka, Aymen Nasri. We would also like to thank all of the team of the Microbiology Laboratory in Fattouma Bourguiba University Hospital for their tremendous effort during this pandemic. We take this opportunity to extend our gratitude to the team of the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at Monastir University.

References

- Bauer Carla M.T., Morissette Mathieu C., Stämpfli Martin R. The influence of cigarette smoking on viral infections: translating bench science to impact COPD pathogenesis and acute exacerbations of COPD clinically. Chest. 2013;143(1):196–206. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman Annechien, Heineman Maas Jan, Faas Marijke M. Sex hormones and the immune response in humans. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(4):411–423. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criteria for Releasing COVID-19 Patients from Isolation. n.d. Accessed 4 February 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/criteria-for-releasing-covid-19-patients-from-isolation.

- Gandhi Monica, Beyrer Chris, Goosby Eric. Masks do more than protect others during covid-19: reducing the inoculum of SARS-CoV-2 to protect the wearer. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;(July) doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi Monica, Rutherford George W. Facial masking for covid-19 — potential for “Variolation” as we await a vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2026913. 0 (0): null. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W.J., Li L.M. [Advances on presymptomatic or asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2020;41(4):485–488. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200228-00207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goronzy J.örg J., Lee Won-Woo, Weyand Cornelia M. Aging and T-Cell Diversity. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(5):400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Xiaowen, Xing Yuhan, Jia Jing, Ni Wei, Liang Jiwei, Zhao Dan. Factors associated with negative conversion of viral RNA in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728(August) doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Chih-Cheng, Shih Tzu-Ping, Ko Wen-Chien, Tang Hung-Jen, Hsueh Po-Ren. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Seungjae, Tark Kim, Eunjung Lee, Cheolgu Lee, Hojung Kim, Heejeong Rhee. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Internal Med. 2020;(August) doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Tong-Zeng, Zhen-Huan Cao, Yu Chen, Miao-Tian Cai, Long-Yu Zhang, Hui Xu, Jia-Ying Zhang, et al. n.d. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA Shedding and Factors Associated with Prolonged Viral Shedding in Patients with COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology n/a (n/a). Accessed 11 August 2020. 10.1002/jmv.26280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ling Yun, Xu Shui-Bao, Lin Yi-Xiao, Di Tian, Zhu Zhao-Qin, Dai Fa-Hui. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin Med J. 2020;(February) doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Kai, Chen Ying, Lin Ruzheng, Kunyuan Han. Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: a comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e14–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Yang, Yan Li-Meng, Wan Lagen, Xiang Tian-Xin, Le Aiping, Liu Jia-Ming. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso Pamela, Venturelli Francesco, Vicentini Massimo, Perilli Cinzia, Larosa Elisabetta, Bisaccia Eufemia. Temporal profile and determinants of viral shedding and of viral clearance confirmation on nasopharyngeal swabs from SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects: a population-based prospective cohort study in Reggio Emilia, Italy. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Hitoshi, Obinata Hirofumi, Murakami Wakana, Tatsuya Kodama, Sasaki Hisashi, Yu Miyake. Comparison of COVID-19 disease between young and elderly patients: hidden viral shedding of COVID-19. J Infect Chemother. 2020;(September) doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.09.003. S1341321X20303238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morone Giovanni, Palomba Angela, Iosa Marco, Caporaso Teodorico, De Angelis Domenico, Venturiero Vincenzo. Incidence and persistence of viral shedding in COVID-19 post-acute patients with negativized pharyngeal swab: a systematic review. Front Med. 2020;7(August) doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patanavanich Roengrudee, Glantz Stanton A. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 Progression: a meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;(May) doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Lin, Yang Yong, Jiang Dixuan, Tu Chao, Wan Lu, Chen Xiangyu. Factors associated with the Duration of viral shedding in adults with COVID-19 outside of Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96(July):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo Seung M., Kim Won Y., Sohn Chang H., Seo Dong W., Oh Bum J., Lee Jae H. Factors promoting the prolonged shedding of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus in patients treated with Oseltamivir for 5 Days. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(5):833–837. doi: 10.1111/irv.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Ding, Wu Wenrui, Wang Qing, Xu Kaijin, Xie Jiaojiao, Wu Jingjing. Clinical characteristics and factors associated with long-term viral excretion in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a single-center 28-day study. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(6):910–918. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ‘Tunisia: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard’. n.d. Accessed 14 February 2021. https://covid19.who.int.

- Wang Kun, Zhang Xin, Sun Jiaxing, Ye Jia, Wang Feilong, Hua Jing. Differences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 shedding duration in sputum and nasopharyngeal swab specimens among adult inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest. 2020;(June) doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ‘WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard’. n.d. Accessed 14 February 2021. https://covid19.who.int.

- Xu Kaijin, Chen Yanfei, Yuan Jing, Yi Ping, Ding Cheng, Wu Wenrui. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;(April) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Fei, Yu Ting, Du Ronghui, Fan Guohui, Liu Ying, Liu Zhibo. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Lirong, Ruan Feng, Huang Mingxing, Liang Lijun, Huang Huitao, Hong Zhongsi. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Eng J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. Letter. 19 February 2020. World. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]