Abstract

Introduction

Ethiopia is one of the countries with the worst road traffic accident records in the world and it ranks second among east African countries. There have not been sufficient studies that mainly reflect the post-crash determinants of deaths and this study was therefore done to assess the overall nature of injuries and the post-crash outcome determinants of road the traffic accident in western part of Ethiopia.

Methods

This was a hospital-based prospective study conducted from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019 using an area sampling technique. Five administrative zones in west Ethiopia were initially selected as a geographical cluster; out of which, four zones were randomly selected. Then, a total of four hospitals were conveniently selected. Finally, 327 people injured in road traffic accidents and brought to the selected hospitals were consecutively included.

Results

Overall, 189 (66.1%) of the casualties have sustained multiple injuries and 65 (24.0%) of them have got severe injuries. About 38.8% and 13.6% have respectively died and discharged with permanent disabilities. A longer distance from receiving hospital (AOR: 1.4, 95% CI [0.48–4.08]), singleness in the number of injury (AOR: 4.3, 95% CI [2.08–9.8]), and lack of receiving pre-hospital care (AOR: 4.072, 95% CI [1.197–13.85]) had statistical associations with increased number of death. On the other hand, injured people who were taken to the hospitals by police officers (AOR: 0.371, 95% CI [0.160–0.860]) than emergency medical technicians and those who were transported by other vehicles (AOR: 2. 58, 95% CI [1.21–5.52]) than ambulance have ironically survived more.

Conclusion

This study concludes that the road traffic accidents related deaths occur largely due to the seriousness of injuries and are exacerbated by lack of adequate pre-hospital emergency care services, costing the lives of many Ethiopians.

Keywords: Road traffic accident, Severity, Patterns, Outcomes, Determinants, Western Ethiopia

African relevance

-

•

The post-crash events associated with deaths reported in this study call for the need for improvement of trauma care system

-

•

The death rate of car accidents in this study is higher than the report from many African countries usually derived from a police report indicating that under reporting is a problem

-

•

The findings of this study is relevant to many African countries with poorly organized emergency service system

Introduction

Road traffic injuries are a major but preventable global public health problem. Worldwide, the number of people killed in road traffic crashes each year is estimated to be 5 million, while the number of injured could be as high as 50 million [1]. Recent pieces of literature reveal that road traffic accidents are expected to have moved from ninth to third place in the world ranking of the burden of disease. World Health Organization report indicates that the road traffic accident is the leading cause of death among people aged 5–44 which has a greater impact on the global economy and health of the population. The organization has calculated the risk of dying in a road traffic crash by continent and Africa is the leading followed by the eastern Mediterranean [2,3].

For its only 4% of the world's motor vehicles, the African road fatality exceeds 10% of the total fatalities. With increasing motorization among African countries, road traffic crashes and injuries are expected to grow at a fast rate, threatening the economic and human development of this poor and promising land. Road crashes in developing countries are more than two-fold of that of developed countries at 13.4/100,000 and 32.2/100,000 people in Europe and Africa respectively. A breakdown of the figure indicates that about 90% of the deaths occur in developing countries. Currently, it is the tenth leading cause of disease burden in the developing countries, especially in the Sub-Saharan African countries [4,5].

According to reported road deaths in selected African countries by region, Ethiopia ranked second next to Kenya among east African countries. The greater percentage of Ethiopia's transportation system is covered by the natural modes like walking and animal transport system leaving only a very negligible share for the motorized aspect. Despite the low rate of motorization in the country, the issue of road safety has already become a critical concern [1,4,5]. Yet through organized and responsive pre-hospital and hospital emergency services, it is possible to potentially reduce deaths due to road traffic accidents that are occurring before the victims reach the hospital.

Due to road transport with poor road infrastructure, low traffic enforcement, and other factors, road traffic accidents remain high in Ethiopia. As such, tragedy from road traffic accidents is steadily increasing and the country is experiencing a tremendous loss of life and property each year probably leading the worst accident record in the world [6,7]. Local reports indicate that more than three thousands of Ethiopians die and ten thousand people are injured because of road traffic accidents. A very recent study in Addis Ababa showed that the fatality rate as a result of the road traffic accidents in the city was 16.1% [8,9].

Geographically, the Oromia regional state serves as the nucleus of the country and is the dominant region in terms of land area and the population. The state accounts for about 14.5% of all accidents and 24% of fatalities which has a high traffic movement next to Addis Ababa in the country [10]. Although there has been no clear picture of road traffic accident-related deaths and disability, it is believed that western Ethiopia also shares its significant burden of the problem.

Beyond the actual seriousness of injuries sustained in road traffic accidents, numerous factors could determine a post-crash fate of casualties. The potential help towards recovery that victims can receive may be viewed as a chain with several links: Delay in detecting crash; difficulty in rescuing and extracting people from vehicles, unprofessional manner of transportation of those injured to a health facility; lack of appropriate pre-hospital care are among crucial determinants of death and survival [11].

In Ethiopia, including the western part of the country, there have been no data indicating mainly post-crash determinants of death from road traffic accidents. Previous studies have largely addressed the mechanics of road traffic accidents. There have been very limited studies carried out to characterize the road traffic accident-related injuries, detect clinical outcomes and predict why the casualties die beyond the seriousness of the actual injury. Moreover, the data on traffic crashes, injuries, and deaths are mostly derived from police reports which do not provide a complete picture of the problem. Therefore, it is with this in mind that this research has motivated to assess road traffic accident patterns, related injury characteristics, severity, post-crash outcome determinants in Western Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted in four hospitals selected from five administrative zones, namely, Buno Bedele, Kelem Wollega, West Wollega, East Wollega and Horo Guduru Wollega, located in Western Oromia, Ethiopia.

Study design

A hospital-based prospective cross-sectional study was conducted from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019.

Population

The source population for this study was all age group people injured and brought to the selected hospitals. The study populations were all injured people in road traffic accidents and presented to the selected hospitals during the specified study period.

Sampling techniques and sampling procedures

Area sampling technique was used to select the hospitals included in the study. Five administrative zones in west Oromia, namely, Buno Bedele, Kelem Wollega, West Wollega, East Wollega, and Horo Guduru Wollega, were primarily selected as geographical clusters. Out of which four zones (Buno Bedele, Kelem Wollega, West Wollega, and East Wollega) were purposively selected. Then, a total of four zonal hospitals was selected (one from each zone). The selected hospitals were similar in their level of services including number of beds and overall standard of services. Finally, consecutive sampling was used to collect the required data from all road traffic accident cases presented and treated in the selected hospitals.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

All road traffic accident victims presented to the respective hospitals that were able to communicate or presented with attendants, treated and followed in the respective hospitals at least for 24 h were included. In addition, victims who have died at the scene or on the way to hospitals were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Due to inability to know what events had happened at the scene and on the road all critically injured patients who did not have attendants were excluded from the study. Since the aim of this study was to observe patients' clinical outcome determinants starting from accident time to the end of the treatment period, all the referred cases from other facilities were not considered in this study. Furthermore, since it was difficult to know their fate, all victims who have got slight injuries and sent to home or to other health facilities were not included in this study.

Research tool and data collection techniques

Data was collected using a comprehensively organized interviewer-administered questionnaires and checklists which were adopted and modified [11]. The tools were comprised of questions used to assess seasonal patterns, injury characteristics, severity and outcome determinants. One characteristic of injury was presence of visceral injuries. This was diagnosed using different diagnostic modalities like ultra sound. Injury severity was measured using the Kampala Trauma Score (KTS) [12]. One more question regarding the main cause of deaths which was responded by two doctors and one nurse was included in the questionnaires. Data was collected by 8 trained nurses (two for each hospital) who have ever worked in the emergency rooms.

Data quality control

The initial tool prepared in English language was translated into the local language (Afan Oromo) and translated back to English by different language experts. Before conducting the main study, data tool testing was carried out in one of the non-selected similar hospital. Based on the findings obtained, further modifications have been made. In addition, investigators have closely supervised the data collection process and necessary corrections were considered on all data collection sites. Moreover, the collected data was checked for completeness before data entry. The cleaning process was done by running simple frequency after data entry to maintain consistency of data. Further checks were done for inconsistency by referring to the hard copy of the study tools.

Data processing and analysis

Data was initially entered into Epi-data version 3.2 by data clerks after several steps of the check for completeness and accuracy. Then, the entered data was exported to SPSS program version 22 for analysis. Descriptive outputs were generated describing the frequency counts and percentages. Binary logistic regression was performed to see the association between certain variables and study outcomes on p < 0.05 for all statistical tests. The variables selected to be included in the multivariate analysis were variables with p < 0.25 in the univariate analysis. Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval was used as a measure of association. Finally, the results of the study were presented using texts, tables, charts, and graphs.

Results

A total of 327 of road traffic accident victims were included in this study and data from 286 participants was analysed; making the response rate of 87.64%. The remaining 41 data were discarded as they were incomplete and inconsistent. The male to female ratio was nearly equal (1.08:1). Age-wise, 117 (40.9%) of the casualties were in the age group of 16–30 years. Relative to the other category, the highest proportion [84 (29.4%)] of the respondents were students in their occupation (Table 1). More than half 170 (59.4%) of the incidents occurred during morning to mid-day and about 3.8% happened at mid-night. Regarding the types of vehicles involved in the accidents, minibus 50(18.7%) and high roof 48(18%) have contributed to the larger percentages. One hundred ninety seven (68.9%) of the accidents were occurred by single vehicles (in which only one car was involved in a particular incident). A higher proportion (49.7%) of the casualties was transported to the receiving hospitals by other vehicles than ambulances (Table 2).

Table 1.

Socio demographic characteristics of road traffic accident casualties in western Ethiopia, 2019.

| No | Variables(N = 286) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age of the patient | <15 years | 39 | 13.6 |

| 16–30 years | 117 | 40.9 | ||

| 31–45 years | 37 | 12.9 | ||

| 46–55 years | 16 | 5.6 | ||

| >55 years | 77 | 26.9 | ||

| 2 | Sex | Male | 149 | 52.1 |

| Female | 137 | 47.9 | ||

| 3 | Religion | Christian | 192 | 67.1 |

| Muslim | 42 | 14.7 | ||

| Wakefata | 29 | 10.1 | ||

| Other | 23 | 8.0 | ||

| 4 | Marital status | Married | 124 | 43.4 |

| Divorced | 18 | 6.3 | ||

| Widowed | 23 | 8.0 | ||

| Single | 121 | 42.3 | ||

| 5 | Level of education | No schooling | 51 | 17.8 |

| Primary school | 90 | 31.5 | ||

| Secondary school | 78 | 27.3 | ||

| College and above | 67 | 23.4 | ||

| 6 | Residence | Town | 85 | 29.7 |

| Rural | 201 | 70.3 | ||

| 7 | Occupation | Government employee | 63 | 22.0 |

| Off sick | 18 | 6.3 | ||

| Student/trainee | 84 | 29.4 | ||

| House keeper/servant | 7 | 2.4 | ||

| Retired | 8 | 2.8 | ||

| Business | 43 | 15.0 | ||

| Farmers | 63 | 22.0 |

Table 2.

Distribution of respondents by their base line information, Nekemte, Ethiopia, 2019.

| No | Information(N = 286) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Time of incidents | Morning to mid-day | 170 | 59.4 |

| Afternoon | 75 | 26.2 | ||

| Mid-night | 11 | 3.8 | ||

| Mid-night to morning | 30 | 10.5 | ||

| 2 | Type of vehicle in which the patient was injured | Sino track | 15 | 5.6 |

| Isuzu | 16 | 6.0 | ||

| High roof | 48 | 18.0 | ||

| Bus | 46 | 17.2 | ||

| Minibus | 50 | 18.7 | ||

| Bajaj | 17 | 6.4 | ||

| Motor cycle | 43 | 16.1 | ||

| Other | 32 | 12.0 | ||

| 3 | Number of vehicles involved | Single vehicle | 197 | 68.9 |

| Multiple vehicles | 89 | 31.1 | ||

| 4 | Situation of the victim during accident | Walking on the road | 42 | 14.7 |

| Fall from a moving vehicle | 72 | 25.2 | ||

| Rolled vehicle | 90 | 31.5 | ||

| Vehicle collision | 71 | 24.8 | ||

| Other | 11 | 3.8 | ||

| 5 | Purpose of vehicle involved in an incident | For private travel | 126 | 44.1 |

| For public transportation | 149 | 52.1 | ||

| Public services provision | 11 | 3.8 | ||

| 6 | Victims role at the time of accident | Pedestrian | 73 | 25.5 |

| Passengers | 117 | 40.9 | ||

| Driver | 56 | 19.6 | ||

| Driver assistant | 40 | 14.0 | ||

| 7 | Distance of scene from receiving hospital | <10 Km | 118 | 41.3 |

| 11–20 Km | 63 | 22.0 | ||

| 21-30 km | 34 | 11.9 | ||

| 41–50Km | 50 | 17.5 | ||

| >51Km | 21 | 7.3 | ||

| 8 | Time elapsed until help arrived in minutes | <15 min | 188 | 65.7 |

| >15 min | 98 | 34.3 | ||

| 9 | Means of transportation to receiving hospital | Ambulance | 134 | 46.9 |

| Other vehicles | 142 | 49.7 | ||

| Carried by people | 10 | 3.5 | ||

| 10 | Accompanying personnel to receiving hospital | Emergency Medical Technicians | 84 | 29.4 |

| Traffic police | 192 | 67.1 | ||

| Bystanders | 10 | 3.5 |

Patterns occurrences, injury characteristics, severity and level of basic cares

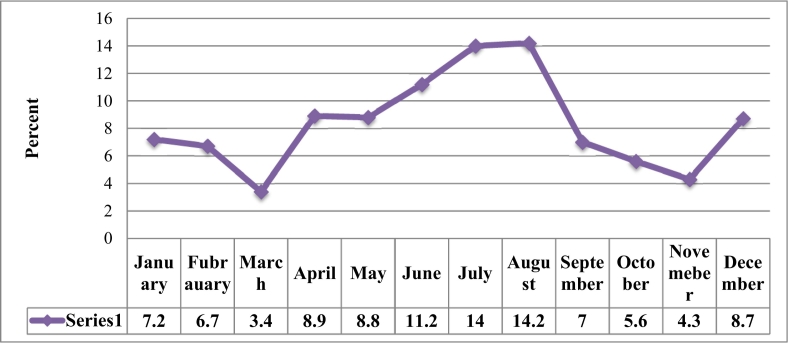

The seasonal pattern of road traffic accidents occurrences at this study area appears to be fluctuating with seasonal changes with a peak of occurrence in the months from May to August (Fig. 1). The vast majority [189 (66.1%)] of the casualties have sustained multiple injuries. Head [55(19.2%)] and chest [55(19.2%)] were the frequently affected body regions relative to others. One hundred sixty one (56.3%) and 156 (54.5%) of the casualties had visceral injuries and bone fractures respectively (Table 3). In this study, injury severity was determined for a total of 269 casualties who have reached the hospitals alive. On spot death (7.7% of total deaths) was conventionally considered as severe injury without considering other physiologic criteria. Out of 269 injured people, 24.16% of them including the 22 and 43 casualties who have died respectively on-scene and during treatment (Table 4). Nearly two-third, 112(74.1%) of injured people did not receive the required minimum emergency care at the scene or during transportation (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Seasonal patterns of road traffic accident occurrence in west Ethiopia, 2019.

Table 3.

Road traffic accident related injury characteristics in Western Ethiopia, 2019.

| No | Injury characteristics | Category | Frequency | Percept |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of injury | Single injury | 97 | 33.9 |

| Multiple injuries | 189 | 66.1 | ||

| 2 | Types of injured body parts | Head and musculo-facial | 55 | 19.2 |

| Neck | 53 | 18.5 | ||

| Chest | 55 | 19.2 | ||

| Abdomen | 44 | 15.4 | ||

| Pelvis | 39 | 13.6 | ||

| Extremities | 40 | 14.0 | ||

| 3 | Visceral injury encountered | Encountered | 161 | 56.3 |

| Not encountered | 125 | 43.7 | ||

| 4 | Types of visceral injury encountered (N = 161) | Spleen | 45 | 27.9 |

| Liver | 26 | 16.2 | ||

| Heart | 17 | 10.5 | ||

| Lung | 18 | 11.1 | ||

| Gastric contents | 32 | 19.8 | ||

| Others | 23 | 14.3 | ||

| 5 | Bone fracture | Fractured | 156 | 54.5 |

| Not fractured | 130 | 45.5 | ||

| 6 | Specific bone fractures encountered (N = 156) | Skull | 35 | 21.7 |

| Clavicle | 27 | 16.8 | ||

| Spinal | 32 | 19.8 | ||

| Rib | 26 | 16.1 | ||

| Pelvic | 20 | 12.4 | ||

| Lower limb | 16 | 9.9 | ||

| Upper limb | 25 | 21.7 | ||

| 7 | Presence of open wound | Present | 139 | 48.6 |

| Not present | 147 | 51.4 |

Table 4.

Description of Kampala Trauma Score and road traffic accident injury severity in west Ethiopia, 2019.

| No | Parameter | Value | Kampala Trauma Severity Score |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |||

| 1 | Age in years | ||||

| <5 | 1 | Mild(13–16) | 21 | 7.81 | |

| 6–55 | 2 | ||||

| >55 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | Number of serious injuries | ||||

| None | 3 | ||||

| One | 2 | ||||

| Two or more | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Systolic blood pressure in mmHg | Moderate(9–12) | 183 | 68.03 | |

| >89 | 4 | ||||

| 50–89 | 3 | ||||

| 1–49 | 2 | ||||

| Undetectable | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Respiratory rate breath per minute | ||||

| 10–29 | 3 | ||||

| >30 | 2 | ||||

| <9 | 1 | ||||

| 5 | Neurologic status | Severe/fatal (5–8) | 65 | 24.16 | |

| Alert | 4 | ||||

| Responds to verbal stimuli | 3 | ||||

| Responds to pain stimuli | 2 | ||||

| Unresponsive | 1 | ||||

| Total | 269 | 100 | |||

Table 5.

Level of basic cares provided for patients injured in road traffic accidents in western Ethiopia, 2019.

| No | Level of basic cares | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Was emergency care given at the scene/during transportation? | Given | 74 | 25.9 |

| Not given | 212 | 74.1 | ||

| 2 | Was the victims immobilized before transportation? | Immobilized | 60 | 20.9 |

| Not immobilized | 226 | 79.1 | ||

| 3 | Further airway intervention | Needed and done | 110 | 38.5 |

| Needed, but not done | 62 | 21.7 | ||

| Not needed | 114 | 39.9 | ||

| 4 | Treatment of tension pneumothorax | Yes, chest drain was placed | 55 | 19.2 |

| Yes, but chest drain was not placed | 191 | 66.8 | ||

| Not evident | 40 | 14.0 | ||

| 5 | Was pulse-oximeter placed and functioning? | Yes, placed and was functional | 246 | 86.0 |

| Available, but not placed | 40 | 14.0 | ||

| 6 | Was oxygen administration needed and given? | Needed and given | 110 | 38.5 |

| Needed, but not given | 62 | 21.7 | ||

| Not needed | 114 | 39.9 | ||

| 7 | Did full survey for and control of bleeding performed? | Performed | 194 | 67.8 |

| Not performed | 92 | 32.2 | ||

| 8 | Was large IV bore placed and fluid started? | Placed and started | 110 | 38.5 |

| Needed, neither placed nor started | 62 | 21.7 | ||

| Not needed | 114 | 39.9 | ||

| 9 | Was blood transfusion needed and given? | Needed and given | 108 | 37.8 |

| Needed but not given | 39 | 13.6 | ||

| Not needed and not given | 139 | 48.6 | ||

| 11 | Does neurovascular status of all four limbs checked? | Checked | 178 | 62.2 |

| Not checked | 108 | 37.8 | ||

| 12 | Was hypothermia likely and prevented? | Likely and prevented | 53 | 18.5 |

| Likely but not prevented | 178 | 62.2 | ||

| Was not likely | 55 | 19.2 | ||

| 13 | Was imaging needed and done? | Needed and done | 79 | 27.6 |

| Needed but not done | 108 | 37.8 | ||

| Not needed not done | 99 | 34.6 | ||

| 14 | Was referral needed and given? | Needed and referred | 55 | 19.2 |

| Given but patient did not go | 53 | 18.5 | ||

| Referral was not needed | 178 | 62.2 |

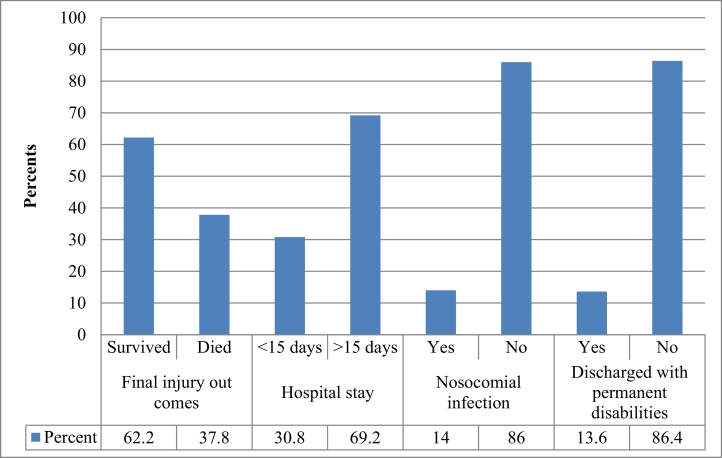

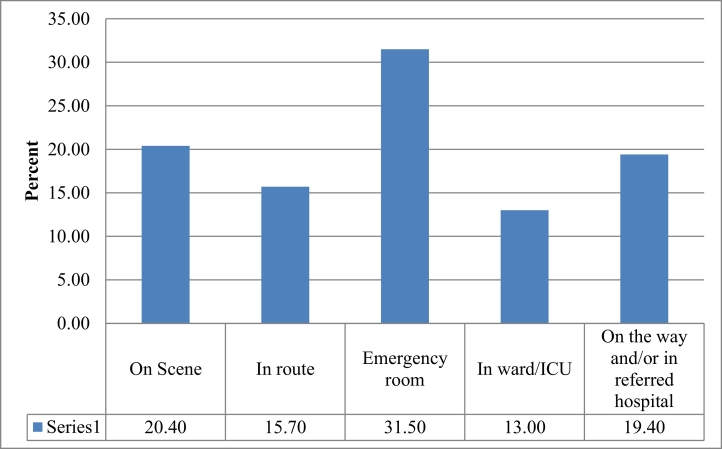

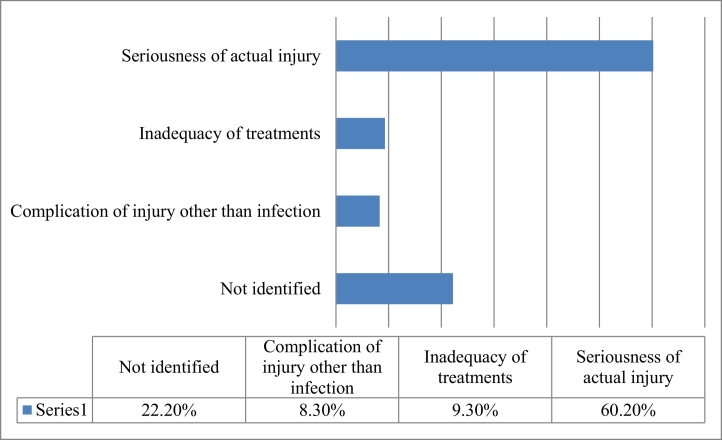

Out of all injured patients, 38.8% of them have died and 13.6% were discharged with permanent disabilities (Fig. 2). Total of (36.1%) have arrived dead (20.4% and on spot death and 15.7% in route death). Thirty one point four 8% of victims died in the emergency department, and the rest of the deaths occurred in the ward/ICU (Fig. 3). Information obtained from the treating physicians and nurses who have also participated on death confirmation was used to identify the main reason of the road traffic accident related deaths. The death occurred outside of the hospitals were considered as death secondary to the seriousness of the injuries and this was 60.2% of all deaths (Fig. 4). The outcome determinants were viewed from three events surrounding road traffic accidents. These were: events that happened immediately after the crash until the victims reach the initial hospitals, the injury characteristics, and the level of treatments provided. Type of vehicle (AOR: 0.292, 95% CI [0.292–0.862]), longer distance from receiving hospitals (AOR: 1.4, 95% CI [0.048–408]) and accompanying personnel (AOR: 0.371, 95% CI [0.160–0.860]) were events associated with the reported number of deaths. Injured people who were taken to the hospitals by police officers (AOR: 0.371, 95% CI [0.160–0.860]) than emergency medical technicians and those who were transported by other vehicles (AOR: 2. 58, 95% CI [1.21–5.52]) than ambulance ironically survived more (Table 6). Similarly, presence of visceral injury (AOR: 2.03, 95% CI [1.021–3.93]) and singleness in number of injury (AOR: 4.3, 95% CI [2.08–9.8]) had statistical significance with number of death (Table 7). Similarly, a longer time elapsed until help arrives (AOR: 4.072, 95% CI [1.197–13.85]) and lack immobilization before transportation (AOR: 2.003, 95% CI [1.021–3.931]) had statistically proved associations with negative outcomes. The need for provision of further airway management (AOR: 1.79, 95% CI [1.045–3.088]) was also associated with chance of dying (Table 8).

Fig. 2.

Road traffic accident related injury outcomes in western Ethiopia, 2019.

Fig. 3.

Place of death among road traffic accident fatalities in west Ethiopia, 2019.

Fig. 4.

Approved main reasons of death among road traffic accident victims in west Ethiopia, 2019.

Table 6.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis between pre accident events and final injury outcomes of road traffic accident in western Ethiopia, 2019.

| Events | Category | Outcome |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | Died | P-value | COR | CI (95%) | AOR | CI (95%) | P-value | ||

| Season pattern | Autumn | 20.8% | 29.6% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | ||

| Winter | 35.4% | 36.1% | 0.037* | 2.626 | [0.1.062–6.494] | 1.29 | [0.658–2.565] | 0.451 | |

| Spring | 14.6% | 27.8% | 0.003* | 5.567 | [0.1.768–17.525] | 2.05 | [0.808–5.216] | 0.131 | |

| Summer | 29.2% | 6.5% | 0.458 | 1.429 | [0.557–3.669] | 0.706 | [0.346–1.441] | 0.339 | |

| Time of occurrence | Morning to mid-day | 55.6% | 65.7% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Afternoon | 38.2% | 6.5% | 0.024* | 8.844 | [0.1.335 58.603] | 3.47 | [0.658–18.329] | 0.143 | |

| Mid-night | 6.2% | 00.0% | 0.037* | 0.354 | [0.134–0.134] | 0.35 | [0.352–1.391] | 0.308 | |

| Mid-night to morning | 00.0% | 27.8% | 0.010* | 4.418 | [0.1.429–13.655] | 1.88 | [0.755–4.704] | 0.175 | |

| Type of vehicle | Sino track | 00.0% | 13.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Isuzu | 00.0% | 14.8% | 0.060* | 0.536 | [0.280–0.280] | 0.292 | [0.292–0.862] | 0.012** | |

| High roof | 30.9% | 00.0% | 0.205* | 0.551 | [0.219–1.385] | 0.45 | [0.208–0.988] | 0.047** | |

| Bus | 3.9% | 36.1% | 0.034* | 2.030 | [1.056–3.903] | 1.79 | [1.045–3.088] | 0.034** | |

| Minibus | 30.9% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Bajaj | 10.7% | 00.0% | 0.071* | 1.789 | [0.951–3.364] | 1.477 | [0.832–2.624] | 0.183 | |

| Motor Cycle | 23.6% | 35.2% | 0.24 | 0.51 | [0.12–1.96] | 0.47 | [0.09–2.34] | 0.30 | |

| Number of vehicles | Single vehicle | 58.4% | 86.1% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Multiple vehicles | 41.6% | 13.9% | 0.024* | 8.844 | [0.1.335 58.603] | 3.47 | [0.658–18.329] | 0.143 | |

| Victims situation | Walking on the road | 10.7% | 21.3% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Fall from a moving vehicle | 19.1% | 35.2% | 0.071* | 1.789 | [0.951–3.364] | 1.477 | [0.832–2.624] | 0.183 | |

| Rolled vehicle | 28.7% | 36.1% | 0.051* | 0.086 | [0.007–1.006] | 0.657 | [0.139–3.106] | 0.597 | |

| Collision | 35.4% | 7.4% | 0.728 | 0.589 | [0.030–11.581] | 4.326 | [0.461–40.637] | 0.200 | |

| Other | 6.2% | 00.0% | 0.058* | 0.072 | [0.005–1.095] | 0.524 | [0.074–3.699] | 0.517 | |

| Purpose of vehicle on travel | Private affair | 54.5% | 26.9% | 0.071* | 1.789 | [0.951–3.364] | 1.477 | [0.832–2.624] | 0.183 |

| Public transportation | 39.3% | 73.1% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Gov./non-govt services | 6.2% | 00.0% | 0.051* | 0.086 | [0.007–1.006] | 0.657 | [0.139–3.106] | 0.597 | |

| Victim's role | Pedestrian | 23.6% | 28.7% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Passengers | 43.8% | 36.1% | 0.284 | 0.133 | 0.058–1.387 | 0.337 | 0.074–1.763 | 0.189 | |

| Driver | 19.1% | 20.4% | 0.099* | 0.361 | [0.108–1.212] | 0.350 | [0.110–1.117] | 0.076 | |

| Driver assistant | 13.5% | 14.8% | 0.324 | 1.348 | [0.744–2.441] | 1.471 | [0.840–2.576] | 0.177 | |

| Distance from receiving hospital | <10 Km | 41.0% | 41.7% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| 11–20 Km | 22.5% | 21.3% | 0.010* | 4.418 | [0.1.429–13.655] | 1.88 | [0.755–4.704] | 0.175 | |

| 21-30 km | 14.6% | 7.4% | 0.050* | 0.407 | [0.166–1.000] | 0.408 | [0.193–0.864] | 0.019** | |

| 41–50Km | 10.1% | 29.6% | 0.00*1 | 0.142 | [0.045–0.445] | 1.40 | [0.048–408] | 0.000** | |

| >51Km | 11.8% | 00.0% | 0.602 | 0.806 | [0.358–1.814] | 0.814 | [0.374–1.771] | 0.604 | |

| Means of transportation | Ambulance | 44.4% | 50.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Other vehicles | 50.0% | 49.1% | 0.008* | 0.259 | [0.095–0.70] | 0.258 | [0.121–0.552] | 0.000** | |

| Carried by people | 5.6% | 00.0% | 0.016* | 0.243 | [0.077–0.768] | 0.22 | [0.098–0.510] | 0.000** | |

| Accompanying personnel | EMT | 11.8% | 58.3% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Traffic police/ | 82.6% | 41.7% | 0.003* | 0.358 | [0.183–0.702] | 0.391 | [0.205–0.748] | 0.005** | |

| Bystanders | 5.6% | 00.0% | 0.042* | 0.335 | [0.117–0.962] | 0.371 | [0.160–0.860] | 0.021** | |

| Communication of emergency personnel to hospitals | Yes | 65.2% | 100.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| No | 34.8% | 00.0% | 0.037* | 0.354 | [0.134–0.134] | 0.35 | [0.352–1.391] | 0.308 | |

Key: * = significant at P-value <0.25, ** = significant at P-value<0.05, EMT = Emergency Medical Technicians.

Table 7.

Multivariate logistic regression between injury characteristics and final injury outcomes of road traffic accident in western Ethiopia, 2019.

| Injury characteristics | Category | Outcome (%) |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | Died | P-value | COR | CI (95%) | AOR | CI (95%) | P-value | ||

| Majorly injured body part | Head and | 00.0% | 50.9% | 0.083* | 0.324 | [0.090–1.160] | 2.88 | [0.83–10.01] | 0.040** |

| Neck | 00.0% | 49.1% | 0.991 | 0.996 | [0.472–2.10] | 0.991 | [0.478–2.054] | 0.981 | |

| Chest | 30.9% | 00.0% | 0.227* | 0.590 | [0.251–1.37] | 0.574 | [0.251–1.312] | 0.188 | |

| Abdomen | 24.7% | 00.0% | 0.285 | 0.545 | [0.179–1.658] | 0.540 | [0.184–1.580] | 0.260 | |

| Pelvis | 21.9% | 00.0% | 0.966 | 1.03 | [0.224–4.71] | 1.110 | [0.248–4.972] | 0.891 | |

| Extremities | 22.5% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Presence of visceral injury | Yes | 77.5% | 50.9% | 0.010* | 2.57 | [1.253–5.38] | 2.003 | [1.021–3.93] | 0.043** |

| No | 22.5% | 49.1% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Presence of open wound | Yes | 41.0% | 100.0% | 0.060* | 0.536 | [0.280–0.280] | 3.0 | [2.92–0.862] | 0.012** |

| No | 59.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Presence of open wound | Yes | 47.2% | 50.9% | 0.294 | 0.451 | [0.102–1.96] | 0.467 | [0.098–2.234] | 0.340 |

| No | 52.8% | 49.1% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Number of injury | Single | 24.7% | 49.1% | 0.205* | 0.51 | [0.219–1.35] | 1.43 | [0.208–1.98] | 0.037** |

| Multiple | 75.3% | 50.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1® | |

| Mental status before hospital arrival | Alert | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| To voice | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.388 | 3.500 | [0.203–60.21] | 2.965 | [0.166–53.098] | 0.460 | |

| To pain | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.204 | 3.897 | [0.478–31.72] | 3.533 | [0.416–29.98] | 0.247 | |

| Unresponsive | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.247 | 3.733 | [0.401–34.74] | 2.626 | [0.266–25.892] | 0.408 | |

| Mental status after hospital arrival (GCS) | <8 | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.285 | 0.545 | [0.17–1.658] | 0.530 | [0.184–1.560] | 0.160 |

| 9–12 | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.966 | 1.34 | [0.224–4.71] | 1.110 | [0.248–4.972] | 0.791 | |

| 13–15 | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

Key: * = significant at P-value <0.25, ** = significant at P-value<0.05.

Table 8.

Multivariate logistic regression between treatment level and final injury outcomes of road traffic accident in western Ethiopia, 2019.

| Treatment | Responses | Outcome |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survived | Died | P-value | COR | CI (95%) | AOR | CI (95%) | P-value | ||

| Time elapsed until help arrives | <15 min | 75.3% | 50.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| >15 min | 24.7% | 50.0% | 0.314 | 0.2280. | 048–2.067 | 0.358 | 0.051–2.511 | 0.302 | |

| Emergency care before arrival | Given | 6.2% | 58.3% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Not given | 93.8% | 41.7% | 0.256 | 0.024** | 0.079–0.833 | 4.072 | 1.197–13.85 | 0.02** | |

| Length of hospitals stay | <7 days | 00.0% | 100.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| 8–14 days | 53.4% | 00.0% | 0.96 | 1.34 | [0.24–4.71] | 1.110 | [0.248–4.72] | 0.891 | |

| >15 days | 46.6% | 00.0% | 0.29 | 0.51 | [0.12–1.96] | 0.467 | [0.08–2.234] | 0.340 | |

| Immobilization at the scene | Immobilized | 14.9% | 85.1% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Not immobilized | 78.8% | 21.2% | 0.010* | 2.570 | [1.23–5.26] | 2.003 | [1.0213.93] | 0.043** | |

| Survey for bleeding control | Done | 71.6% | 28.4% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Not done | 42.4% | 57.6% | 0.314 | 0.2280. | 048–3.067 | 0.358 | 0.051–2.511 | 0.203 | |

| Infection after admission | Acquired | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.284 | 0.122 | 0.058–1.397 | 0.337 | 0.064–1.763 | 0.198 |

| Not acquired | 56.1% | 43.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Further air way management | Needed and done | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.20* | 0.551 | [0.219–1.385] | 1.45 | [2.08–9.88] | 0.047** |

| Needed, but not done | 43.5% | 56.5% | 0.034* | 2.030 | [1.056–3.90] | 1.79 | [1.04–3.08] | 0.034** | |

| Not needed | 84.2% | 15.8% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Presence of Tension pneumothorax and it treatment | Yes, chest drain was placed | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.458 | 1.429 | [0.557–3.669] | 0.706 | [0.346–1.41] | 0.339 |

| Yes, chest drain was not placed | 72.3% | 27.7% | 0.037* | 2.626 | [0.1.06–6.44] | 1.29 | [0.658–2.55] | 0.451 | |

| Not evident | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Need and provision of pulseoximeter | Available and placed | 56.1% | 43.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Available, but not placed | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.22* | 0.590 | [0.251–1.387] | 0.574 | [0.251–1.31] | 0.188 | |

| Need and provision blood transfusion | Needed and given | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.099* | 0.361 | [0.108–1.212] | 0.350 | [0.110–1.17] | 0.076 |

| Needed, not given | 100.0% | 00.0% | 0.324 | 1.348 | [0.744–2.441] | 1.471 | [0.840–2.56] | 0.177 | |

| Not needed | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Hypothermia and prevention | Likely and prevented | 00.0% | 100% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Likely but not prevented | 69.1% | 30.9% | 0.045* | 2.030 | [1.056–3.90] | 1.79 | [1.04–3.08] | 0.034** | |

| Neurovascular check | Checked | 69.1% | 30.9% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) |

| Not Checked | 50.9% | 49.1% | 0.285 | 0.545 | [0.179–1.658] | 0.540 | [0.184–1.50] | 0.260 | |

| Need and provision of imaging | Needed and done | 100.0% | 00.0% | ||||||

| Needed but not done | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.728 | 0.589 | [0.030–11.1] | 4.326 | [0.61–40.67] | 0.200 | |

| Not needed not done | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

| Referral to better centre | Needed and referred | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.204 | 3.87 | [0.478–31.72] | 3.533 | [0.416–29.98] | 0.247 |

| Given but did not go | 00.0% | 100.0% | 0.96 | 1.03 | [0.224–4.71] | 1.110 | [0.248–4.92] | 0.891 | |

| Referral not needed | 100.0% | 00.0% | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | 1(R) | |

Key: * = significant at P-value <0.25, ** = significant at P-value<0.05.

Discussion

Numerous studies have revealed that there has been a consistent increase in the absolute number of road traffic accidents in many of the developing nations over the last several decades. This study has examined the injury characteristics, seasonal patterns of occurrences, injury severity, and outcome determinants of road traffic accidents in the western part of Ethiopia. The key findings of this study related to injury characteristics, determinants of clinical outcome are compared and contrasted with and against the existing works of literatures. The findings of this study in general and the key findings stressed in this discussion section in particular are aimed to provide essential information as to what post-crash factors have contributed to the reported death from road traffic accidents in the present study.

The potential help towards recovery that victims can receive may be viewed as a chain of several links: actions or self-help at the scene of the crash by the victims themselves, or more frequently by bystanders; Access to the emergency medical system, helps provided by rescuers of the emergency services; delivery of medical care before arrival at the hospital, and the hospital trauma care services [10,11]. In the present study, higher proportions (49.7%) of casualties were transported to the receiving hospitals by other vehicles than ambulances and 192(67.1%) of the victims were accompanied by traffic polices than emergency care personnel, indicating lack of appropriate pre-hospital emergency help.

Injury severity is often used as a measure of the health consequences of road traffic crashes. Injuries are classified as fatal, serious or slight on the basis of information available to the police within a short time after the crash. Classifications may not reflect the results of a medical examination and are largely influenced by whether a casualty is hospitalized or not [13]. As a secondary motive, this study determined road traffic accident-related injury severity. According to Kampala Trauma Score classification of trauma severity, the majority (68.02%) of injured people in this study sustained moderate injury and 24.0% sustained severe (fatal) injury.

The final injury outcome of road traffic accidents was measured in terms of death versus survival, complications developed and length of hospital stay. The high percentage of fatalities indicates a critical lack of pre-hospital and emergency medical services [11,14,15]. In Ethiopia, of the total traffic accidents occurring yearly, more than 20% of the total traffic accident injuries are fatal [6]. In the current study, out of all injured patients who have admitted to the selected hospitals, 38.8% of them have died. This finding is much higher as compared to findings reported from similar other studies carried out in Ethiopia [9., [10], [11],16]. The observed discrepancy, on one hand, might be due to the fact that many of the reports by traffic police are only limited to on spot death which is usually subjected to an undercount of the actual numbers of fatalities. On the other hand, many of the victims who have sustained minor injuries and who have not met the admission criteria were excluded from this study which might have contributed to relatively a higher records of death reported in this study.

The duration of hospital stay has been viewed as an important measure of morbidity among trauma cases [17,18]. Prolonged hospitalization, especially in a setting like Ethiopia where resource is critically limited could pave the way for unnecessary severe nosocomial infections; which at the end negatively affects patient outcomes. The overall mean length of stay (11.16 days) of this study was slightly higher compared to the duration of days reported from comparable studies [19,20].

Delays in detecting crash and in the transport of those injured to a health facility; lack of appropriate pre-hospital care; lack of appropriate care in hospital emergency rooms are among important determinants of potential injury outcomes [13]. Transporting mass casualty without communicating to the receiving facility before casualty's arrival could also affect the end outcome of the injured people. This is because of the fact that the earlier the facilities get informed about the incoming victims, the sooner and the better they get prepared. Minimizing delay in the initiation of care and treatment option related confusions will ultimately benefit the patients. In this study, 21.7% of the injured people were transported without reporting to the hosting hospitals.

Most importantly, the pre-hospital care of trauma patients has been reported to be the most important factor in determining the ultimate outcome after the crash [21]. Nearly two-third (74.1%) of injured people in this particular study did not receive the required minimum Emergency care at the scene or during transportation.

The special emphasis of this study was to find out possible determinants of injury outcomes both before and after hospital arrival. In this study, the outcome determinants were viewed from three events surrounding road traffic accidents. There have been statistically approved correlations between death and selected events immediately after the crash until the victims reach or admitted to the initial hospitals.

The long distance from receiving hospital (p-value <0.00) has increased the likelihood of dying. The patients who were accompanied by police officers than emergency medical technicians (p-value <0.021) and who were transported by other vehicles(p-value: 0.00) than ambulance have survived more. These findings are inconsistent with the findings reported from similar studies conducted elsewhere [[21], [22], [23], [24]]. The reason for this could be due to the reality that number of ambulances and emergency personnel are critically limited in this region and the existing ambulances are usually reserved for special transportation like for delivering mothers.

Similarly, injury characteristics including but not limited to majorly injured body parts (p-value <0.040), presence of visceral injury (p-value <0.043), and a single number of injuries (p-value <0.037) had statistically significant associations with the number of death. These findings are generally in line with the findings that have been reported from different countries across Africa and India [[25], [26], [27]].

Conclusion

This study concludes that the road traffic accidents related deaths occurring largely due to the actual seriousness of injuries that and are evidently exacerbated by lack of adequate pre-hospital emergency care services, are still costing the lives of many Ethiopians. Therefore, instituting a sound primary prevention strategies and establishing a strong pre-hospital emergency system are further works yet to be done.

Although this is a prospective study, the sample size of 286 may not be a satisfactory reflection of the true nature of the problem under study. Additional limitation is that the difficulty to account for all confounders, some missing data that might skew the data one way or the other, and the % dead may actually be less given exclusion of patients with minor injuries discharged from the hospitals. Moreover, this study has used information from the treating physicians and nurses than a standard way to report for reasons of deaths (post-mortem). On the other hand, the prospective nature of study design has enabled the researchers to deal with the actual outcome determinants which might otherwise impossible to achieve using retrospective type.

Dissemination of results

Results from this study were shared with Wollega University Ethics committee and staff members through formal presentation. The results were also published in the service's newsletter.

Authors' contribution

Authors contributed as follow to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: AHW contributed 60%; WDH 25%; and NHT, and BKM contributed 15% each. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2020.09.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Odero W., Khayesi M., Heda P.M. Road traffic injuries in Kenya: Magnitude, causes, and status. 2003;10(1–2):53–61. doi: 10.1076/icsp.10.1.53.14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adewale M.A., Akinola A.F., Ambrose R., Temitope A. Epidemiology of road traffic crashes among long distance drivers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr Health Sciv. 2015;15(2) doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i2.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noked Noam. Harvard University’s DASH repository; 2010. Providing a corrective subsidy to insurers for success in reducing traffic accidents; pp. 3–59.http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4889453 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Greg. Road traffic safety in African countries – status, trend, contributing factors. Counter Measures and Challenges. 2010:247–255. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2010.490920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeepura P., Pirasath S. Road traffic accidents in eastern Sri Lanka: an analysis of admissions and outcome. Sri Lanka Journal of Surgery. 2012;29(2):72–76. doi: 10.4038/sljs.v29i2.3945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Status Report on Road Safety: Time for Action. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44122/.../9789241563840_eng.pdf Report. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs G., Aeron-Thomas A., Astrop A. Estimating global road fatalities. Transport Research Laboratory. 2000:445. https://www.researchgate.net/.../252247841 ISSN 0968-4107. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toroyan T, Harvey A, Bartolomeos K, Laych Kea. Global status report on road safety: Time for action. 2016; vol. 23:46 DIO: 10.11604/pamj.2016.23.46.7487, http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/23/46/full/.

- 9.Kebede A. 2016. Road Traffic Accident related Fatalities in Addis Ababa City, Ethiopia: An Analysis of Police Report 2013/14; pp. 7–13.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2720414/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teferi A., Yemane B., Alemayehu W., Abebe A. Effectiveness of an improved road safety policy in Ethiopia: an interrupted time-series study. Bio Med Central. 2014;14(539) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-539. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262777017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seid M., Azazh A., Enquselassie F., Yisma E. Injury characteristics and outcome of road traffic accident among victims at adult emergency Department of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a prospective hospital based study. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15(10) doi: 10.1186/s12873-015-0035-4. https://bmcemergmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10../s12873-015-0035-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macleod J.B.A., Kobusingye O., Frost C., Lett R. KmpalaTrauma Score(KTS): is it a new triage tool, east and central African. Journal of Surgery. April 2007;12(1):74–82. https://www.researchgate.net/.../27799668 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osoro M.E., Ng’ang’a Z., Oundo J J., Luman Omolo E. Factors associated with severity of road traffic injuries. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;8:20. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71076. https://europepmc.org/article/med/22121429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osoro, Ng’ang’a Z., Yitambe A. An analysis of the incidence and causes of road traffic accident in Kisii, central district, Kenya. OSR Journal Of Pharmacy. September 2015;5(9):41–49. doi: 10.4314/pamj.v8i1.71076. https://www.ajol.info//index.php/pamj/article/view/71076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinand M., Nantulya, Reich Michael R. The neglected epidemic: road traffic injuries in developing countries. BMJ (online) 2002;324(7346):1139–1141. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7346.1139. June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalya P.L., Mabula J.B., Dass R.M., Mbelenge N., Ngayomela I.H., Chandika A.B. Citywide trauma experience in Mwanza, Tanzania: a need for urgent intervention. J Trauma Manage Outcomes. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1752-2897-7-9. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1752-2897-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krug E.G., Sharma G.K., Lozano R. The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health. 2000 Apr;90(4):523–526. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.523. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10754963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hailu T. Road crashes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: empirical findings between the years 2010 and 2014. AFRREV. APRIL, 2017;11(2):1–13. doi: 10.4314/afrrev.v11i2.12.1. https://www.researchgate.net/.../317033241 SERIAL NO. 46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adebayo Lawrence O.J.O. Assessment of human factors as determinants of road traffic accidents among commercial vehicle drivers in Gbonyin local government area of Ekiti state, Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME) Jan - Feb. 2015;5(1):69–74. doi: 10.9790/7388-05116974. www.iosrjournals.org Ver. I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twagirayezu E., Teteli R., Bonane A., Rugwizangoga E. Road traffic injuries at Kigali University Central Teaching Hospital, Rwanda. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2008;13(1):73–76. http://www.bioline.org.br/js 13. eISSN: 2073-9990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan K.M., Jamil M., Memon I.A., Idrees Z. Pattern of injuries in motorbike accidents. Journal of Pakistan Orthopaedic Association. 2018;30(03):123–127. http://jpoa.org.pk/index.php/upload/article/view/245 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akinpelu O.V., Oladele A.O., Amusa Y.B., Ogundipe O.K., Adeolu A.A., Komolafe E.O. Review of road traffic accident admissions in a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2007;12(1):64–67. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.153230. https://europepmc.org/article/pmc/pmc4387814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naddumba E.K. A cross-sectional retrospective study of Boda Boda injuries at Mulago hospital IN Kampala-Uganda. East and Central African Journal of Surgery. 2004;9(1):44–47. https://www.researchgate.net/.../27799549 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tulu G.S., Washington S., King M.J. Conference: Australasian road safety research, Policing & Education Conference. August 2013. Characteristics of police-reported road traffic crashes in Ethiopia over a six year period; pp. 1–5.http://acrs.org.au/files/arsrpe/Paper%20139%20-%20Tulu%20-%20Cultural%20 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woyessa A.H., Dibaba B.Y., Hirko G.F., Palanichamy P. Emergency Medicine International; 2019. Spectrum Pattern, and Clinical outcomes of Adult Emergency Department Admissions in selected Hospitals of Western Ethiopia- A hospital-based prospective study.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6701330 (Hindawi emergency medicine international volume 2019). Article ID 8374017, 10 pages. Vol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abegaz T., Berhane Y., Worku A., Assrat A., Assefa A. Road traffic deaths and injuries are under-reported in Ethiopia: a capture-recapture method. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e103001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103001. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Alidianne F.C., de Belchior M.L., BSO Thaliny, Christiane L.C., Sérgio d’A, Alessandro L.C. Fatal road traffic accidents and their relationship with head injuries: an epidemiological survey of five years. Pesquisa Brasileira em Odontopediatria e Clinica Integrada. 2017;17(1):e3753. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.