Abstract

Genetic redundancy has evolved as a way for human cells to survive the loss of genes that are single copy and essential in other organisms, but also allows tumours to survive despite having highly rearranged genomes. In this study we CRISPR screen 1191 gene pairs, including paralogues and known and predicted synthetic lethal interactions to identify 105 gene combinations whose co-disruption results in a loss of cellular fitness. 27 pairs influence fitness across multiple cell lines including the paralogues FAM50A/FAM50B, two genes of unknown function. Silencing of FAM50B occurs across a range of tumour types and in this context disruption of FAM50A reduces cellular fitness whilst promoting micronucleus formation and extensive perturbation of transcriptional programmes. Our studies reveal the fitness effects of FAM50A/FAM50B in cancer cells.

Subject terms: Cancer, Genetics, Molecular biology

Systematic screens for synthetic lethal gene pairs represent a powerful approach to define interactions that may be exploited in the clinic. Here, the authors use a dual-guide CRISPR screening approach to screen a curated selection of gene pairs across three cell lines and validate the Fam50a/Fam50b synthetic lethality was in isogenic cell models as well as in an in vivo setting.

Introduction

A major precept of cancer genetics is that normal cells acquire somatic mutations that provide a fitness advantage and drive tumour evolution and growth. Since these alterations are generally not found in normal cells, they may be exploited therapeutically, either by direct pathway inhibition, for example, in the context of activated oncogenes, or via synthetic lethality. The concept of synthetic lethality was pioneered by the yeast and Drosophila genetics communities who realised that the disruption of multiple genes simultaneously could elicit cell death in situations where disruption of such genes singly did not1. In more recent times, synthetic lethality has been exploited as an approach to treat cancers, the most notable example being the development of PARP inhibitors to treat patients with BRCA1/2 mutant tumours2–4. Although substantial efforts have been made to identify synthetic lethal (SL) interactions in human cancer cells, we are still a significant way from having a genome-wide map of cancer dependencies, with many established SL interactions appearing to be highly context dependent5. Thus, systematic screens for SL gene pairs represent a powerful approach to define interactions that may be exploited in the clinic and to understand the context dependencies in which they operate.

The mammalian genome has evolved to carry parallel pathways or in some cases multiple redundant genes on which cells rely for survival—the principal reason for these gene sets seems to be to buffer and protect cells from the adverse consequences of gene loss, allowing cells to operate with higher fidelity and/or plasticity, even under stressful conditions. One set of these genes are the paralogues; genes derived from a common ancestral gene that now reside in different regions of the genome6–9. As above, several theories have been proposed for the creation of paralogues, one being that paralogues have developed to create functional redundancy, presumably as a result of selective pressure. Examples of essential paralogues include RPL22L1 and RPL22, which are ribosomal proteins, and YAP1/WWTR1(TAZ) in the Hippo pathway9. Importantly, although several paralogue dependencies have been established, we are currently unable to accurately predict which paralogue pairs may be essential or functionally related by their sequence alone. Intriguingly, many essential paralogue pairs are part of the same protein complex8. A good example of this are components of the BAF/PBAF complexes, such as ARID1A/ARID1B and SMARCA2/SMARCA4, which are required for a range of processes such as transcription and chromatin regulation10,11. Disruption of these gene pairs results in growth arrest and cell death; phenotypes which appear to be influenced by cell lineage and differentiation status12.

As noted above, cancer cell line screens are powerful tools for the identification of SL interactions because they can be used to systematically and comprehensively screen the genome without making any prior assumptions about which genes interact5,13. Generally, these screens have been performed using either compounds/targeted-agents, shRNA/siRNAs, or more recently with CRISPR14–17. Many of these screens have been performed in the context of specific genetic changes, such as in panels of cells with defined genetic alterations, or in isogenic cell lines, so that genetic interactions can be readily identified15,18. More recently, it has become possible to use paired gRNAs, also known as combinatorial or multiplex CRISPR screening, to identify essential gene pairs19–24. This approach to exploring genetic epistasis facilitates the identification of gene combinations that are SL by screening at scale. Here, we deployed CRISPR screening to interrogate 1191 gene pairs including 645 paralogues, 447 mutually exclusive genetic interactions defined using mutual exclusivity modelling of cancer data, and a set of 95 literature curated SL pairs. Our screening of two melanoma cell lines (A375 and MeWo) and a retinal epithelial line (RPE-1) identified 27 SL pairs occurring in ≥2 cell lines. This included the poorly characterised Family with sequence similarity 50 Member A & B (FAM50A/FAM50B) gene pair, whose disruption precipitates a loss of cellular fitness associated with apoptosis and widespread dysregulation of transcription. FAM50A/FAM50B are particularly notable among our collection of genetic interactions because ~4% of cancers profiled by the TCGA show loss of FAM50B expression (0–10% across tumour categories), thus highlighting the FAM50A/FAM50B axis as a potential therapeutic target.

Results

Selection of gene pairs for combinatorial screening

Gene pair sets were chosen to be included in our library based on three distinct biological rationales (Fig. 1A). The first of these was a set of putative SL partners derived from two published bioinformatic analyses of human mutation and expression data25,26, where pairs of genes had been identified as ‘co-lost’ less frequently than expected by chance. We intersected the gene sets from these studies, resulting in 447 overlapping candidate pairs for which gRNAs could be designed. The second gene set consisted of the 95 highest scoring gene pair interactions for which gRNAs could be designed as defined by a curated database of SL interactions (SynLethDB)27. Notably, this set of genes includes pairs derived from a vast array of biological contexts and tumour types, allowing us to assess if these interactions were essential in our system and in the cell lines we screened. Our library also included gRNAs for four gene pairs to test interactions between PARG1/XRCC1, KDM6A/UTY, KDM6A/KDM6B and KDM6B/UTY, implicated from genome sequencing studies28. The final gene set consisted of paralogous pairs. To define these genes, we built a computational pipeline to identify paralogue pairs (two-member paralogue families) with >20% DNA sequence homology/similarity and filtered this collection to identify genes where there was a single common orthologue in either Caenorhabditis elegans (Wormbase; WS251) or Drosophila melanogaster (Flymine; FB2015_05) and where disruption of this gene resulted in death of the organism. In this way, we identified 701 gene pairs, 645 of which were amenable to targeting by CRISPR (see Methods). In order to assess the performance of our library we also included a panel of established essential and non-essential genes29,30. A complete list of all gene pairs is provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Fig. 1. Combinatorial CRISPR screen for cancer targets.

A Schematic of the genes and gene pairs included in the paired gRNA library. The number of gene pairs for which the minimum guide number could be identified with our gRNA selection criteria is shown. The number in brackets is the total number of pairs in each category. B Design of the multiplex gRNA construct. To assess single-guide activity, a non-targeting gRNA (Fluc) was placed under the hU6 promoter and the gRNA against the candidate gene was placed under the sU6 promoter. To assess paired gene activity, all five gRNAs for one gene were under the hU6 promoter, whereas the guides targeting the other gene were under the sU6 promoter. C Derivation of residual values. The predicted log2-fold change (FC) of the paired construct was calculated from the sum of the growth phenotypes of individual guides and the observed (experimentally determined) log2FC was the actual behaviour of the pair in the screen. The behaviour of the population was modelled using Loess smoothing (blue line). The residual was calculated as the vertical difference of any given point to the blue line. The more negative the residual, the more lethal the pair in the screen. The behaviour of the gRNA pairs for the nine synthetic lethal interactions common to all cell lines is shown in the A375 cell line. D Overlap between the synthetic lethal pairs identified in the screen in each of the three cell lines at Day 28. Significant gene pairs were defined as having a significantly more lethal pairwise effect on cellular fitness than expected from the effect of each individual gene (see Methods). Pairs where one of the genes was found to be lethal in isolation at Day 14 were excluded. E Percentage DNA sequence similarity between paralogues in our screen, identified as synthetic lethal in ≥1 cell line (Ever SL) vs zero cell lines (Never SL). Error bars show mean and standard deviation (SD) with each data point representing the average sequence similarity between paralogue pairs (see Source Data). The p value was determined using the two-tailed Mann–Whitney test.

Library design, construction and cell line screening

Our library was constructed using a dual promoter system (human U6 and synthetic U6) and was assembled using Gibson cloning31. We designed 3–5 guides for each gene and placed guides together as pairs and also paired each of them with a non-targeting/control guide, to allow assessment of both guide–guide and single-guide activity (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Data 11–4 and Methods). Prior to library construction, the efficiency of the paired gRNA construct was confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), utilising guides against two cell surface markers (CD15 & CD33)32 (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 2). We used our library to screen two deeply characterised melanoma cell lines (A375 and MeWo), and RPE-1 cells that are near-diploid and non-transformed and thus represents a ‘normal’ comparator. After lentiviral integration of Cas9, Cas9 activity (≥90%) of each cell line was confirmed using a reporter assay32 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Screens were performed in technical triplicate at 1000× representation for a total of 28 days, harvesting cells for DNA extraction and sequencing at day 14 and 28 (see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Methods). Baseline values for gRNA abundance were generated by infecting a non-Cas9-positive cell line in triplicate in matched conditions to the dropout screen. These cells were harvested at day 7.

Benchmarking of screen performance

Before exploring our data set for genetic interactions we elected to perform some benchmarking analyses. To do this, we first used both MAGeCK33 and BAGEL29 to compare the profile of gene essentiality by comparison of the screen results to established essential and non-essential genes, which were included in the library as controls (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). For all three cell lines, this analysis revealed a screen performance equivalent to previous large-scale single gRNA screens34.

Analysis of combinatorial CRISPR screen data

The analysis to identify interacting gene pairs was based on the Bliss model of additivity35, whereby the effect of the gRNA pair was predicted from the behaviour of each of the gRNAs by themselves (Fig. 1C). Using this approach, we calculated both the expected and observed lethality (fitness effect) of each gene pair and created a population-based model (see Methods). In this way, for each given gene pair, we were able to ascertain if the gene pair was significantly more lethal, which in this context means more depleted from the library transduced cell population, than expected by comparing the lethality of the pair to the lethality associated with individual gRNAs paired with a non-targeting/control gRNA. Using this approach, we identified between 177 and 201 candidate SL interactions per cell line, representing pairs of genes that significantly impaired cellular fitness. Given the number of SL pairs identified, we filtered the data to obtain a high-confidence set of gene pairs. First, we observed that several of the pairs identified as being potential candidate SL interactions contained a single gene with a strongly negative growth phenotype. We reasoned that this could be because some gRNAs were more efficient at disrupting their target gene or that there were subtle imbalances in the strength of the promoters used in the vector21. Thus, we filtered from our hits any pairs containing a gene defined as essential in either our screen (gRNA against a gene paired with a non-targeting gRNA) at day 14 (to select genes whose loss resulted in a cytotoxic rather than cytostatic effect), or an independent screen performed on each respective cell line using a whole-genome single gRNA CRISPR library34 (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 3). This approach refined our candidate list to 40–57 candidate SL interactions per cell line. Of the SL pairs identified in our screen ~26% (27/105) were observed in two or more cell lines and nine were found in all cell lines screened (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Data 5).

SL is enriched between paralogous gene pairs

Among the hits we identified, paralogues were highly over-represented (72/105 interactions, p = 0.002 two-tailed Fisher exact test), and all of the nine interactions common to all three cell lines were paralogues (Fig. 1D). Paralogues identified as SL gene pairs had a higher pairwise DNA sequence similarity than non-SL paralogues (p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Mann–Whitney test); Fig. 1E and Source Data), most likely because as homology decreases, redundancy between pair members also decreases. SL paralogues also had a higher DNA sequence similarity than non-lethal paralogues when compared with orthologues in simpler organisms (C. elegans/D. melanogaster) (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Source Data).

Validation of SL pairs

We took eight individual gene pairs identified as SL (five pairs identified as SL in 3/3 cell lines, two pairs in 2/3 cell lines, one pair in 1/3 cell line), selected based on their recurrence or biological interest, and proceeded to validate these pairs using competitive cell growth assays. To do this, we placed a gRNA targeting one of the genes in the pair in a mCherry-expressing vector, and another, targeting the other gene, in a BFP-expressing vector (see Methods). We transduced cells with both vectors to create four populations (see below), and measured population dynamics at timepoints between day 4 and 14 (Fig. 2A–B). These populations were either red or blue fluorescent, where a single gRNA had been transduced, untransduced cells with no fluorescence, or blue/red where both gRNAs had been introduced. For each cell line (A375, RPE-1, and MeWo) we established a baseline between non-interacting gene pairs by selecting two non-essential genes (ACCSL/AIPL1)29 and calculated the residual, representing a baseline neutral genetic interaction in each cell line (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 7). We next compared the residual of each candidate SL gene pair to that of the non-interacting pair, additionally including two extra ‘non-interacting pairs’ as negative controls. The concordance rate between our validation experiments and the screen output was 95% (8/8 interactions in two cell lines, 7/8 in one cell line) (Fig. 2C and Source Data). Supplementary Fig. 8 and Source Data shows the fitness effects of disrupting each gene in the pair and the predicted and observed lethalities as waterfall plots.

Fig. 2. Validation of candidate synthetic lethal pairs.

A Schematic of the competitive growth assay. Cas9-expressing cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing each gRNA in a BFP or mCherry vector to create four populations and read by FACS at day 4 and 14. B Example of a synthetic lethal pair. A375-Cas9 cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing CNOT7 (BFP) and CNOT8 (mCherry) sgRNAs and analysed at two timepoints. The growth phenotype was calculated by measuring the relative depletion of the single-infected and double-infected cells. C Residual values from competitive growth experiments. Residuals were calculated as the difference between the expected phenotype of the double-positive population (based on summing the phenotypes of the single positive populations) and the observed phenotype of the double-positive population. Data represent three independent transductions. The baseline residual for three non-interacting-pairs (negative controls) are also shown (AIPL1&ACCSL, AIPL1&ASF1B, TTC7A/ACCSL). Residuals were compared with values for the control ACCSL/AIPL1 gene pair. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA and adjusted for multiple testing using the Dunnett test. All interactions, except where indicated, had a P value < 0.01.

Comparison of the screen results to other data sets

Across the cell lines screened in this study we identified a rich collection of SL interactions, several of which were validated as described above. To extend this analysis we compared our data to other previously generated SL data sets (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Data 7). Specifically, we first looked for an overlap with the SL interactions computationally predicted by De Kegel et al.8, revealing 167/234 overlapping gene pairs were in agreement with 22 of these pairs ‘hits’ in both studies. These pairs included EAF1/EAF2, DDX39A/DDX39B and CHMP1A/CHMP1B. In the same way, we compared our data set to a study by Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis et al.22 Noting that RPE-1 was the only cell line screened in both studies, 94/170 overlapping genes pairs were concordant as either hits or non-hits. Of these, 17 were defined as SL interactions in both studies. These interactions included CNOT7/CNOT8, TTC7A/TTC7B and SAR1A/SAR1B, all of which are paralogous gene pairs. The gene pairs ARID1A/ARID1B, SEC23A/SEC23B, SLC25A28/SLC25A37, SMARCA2/SMARCA4, TTC7A/TTC7B and UAP1/UAP1L1 were hits in all three data sets. Collectively, this analysis orthogonally validates nearly 40 SL interactions and also the quality of our screen.

Identifying potentially therapeutically relevant genetic interactions

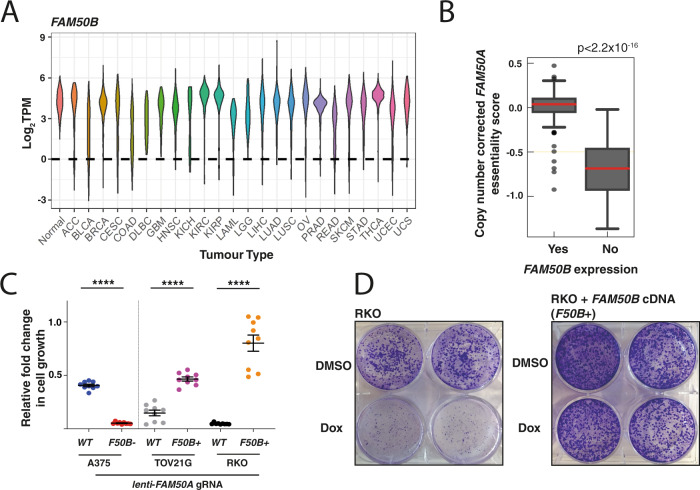

We assessed the gene pairs identified as SL by our screen for their cancer-translational potential using TCGA expression data36. First, we searched for pairs where one member was not expressed in a tumour type reasoning that disruption of the other member of the pair may result in reduced tumour cell fitness. Interestingly, we observed FAM50B expression to be lost in tumours across a wide range of histological types including melanoma, bladder and colon cancer whereas it was ubiquitously expressed in normal tissue (Fig. 3A). Specifically, 355/9263 (4%) of tumours have a TPM < 1 (range 0–10% across tumour categories) (Supplementary Data 6). Of note, FAM50B is an imprinted gene with a paternal expression pattern, rendering it susceptible to copy number events and loss of heterozygosity37,38. Analysis of genome-wide methylome data revealed FAM50B promoter methylation in cell lines that had lost expression of the gene (Supplementary Fig. 10). Collectively, these data suggest that a proportion of human cancers could be selectively targeted by disruption or suppression of FAM50A.

Fig. 3. The FAM50A/FAM50B axis is a targetable synthetic lethal interaction.

A Expression of FAM50B across tumour and normal tissue. Data obtained from the TCGA36. TPM; transcripts per million. Standard TCGA tumour abbreviations where used. B FAM50B expression inversely correlates with dependency on FAM50A. These data were derived from the analysis of CRISPR essentiality in 275 cancer lines34. Lines were categorised by their FAM50B expression using an RPKM cutoff of 1 below which expression was defined as absent. The dependency of FAM50A is shown as scaled log2 fold-change of FAM50A gRNAs corrected for copy number variation across the cell lines used in this analysis. The p value was calculated with a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Box-and-whisker plots show 1.5× interquartile ranges and 5–95th percentiles, centres indicate medians. C Analysis of essentiality using isogenic cell lines. TOV21G-Cas9 and RKO-Cas9, which do not express FAM50B, were transduced with a lentivirus expressing a FAM50B cDNA (F50B+). A375-Cas9 cells express both FAM50A and FAM50B. A FAM50B knockout clone was generated for this cell line (F50B−) using CRISPR. Cells were transduced with a BFP+ lentivirus carrying a gRNA against FAM50A such that 50% of cells were transduced. Cell proportions were analysed at day 4 and 14. The relative fold-change of the infected population is shown. p values were obtained using the unpaired two-tailed t test, ****p < 0.0001. Experiments were performed on three separate occasions in triplicate. Error bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM). D Clonogenic confirmation of the FAM50A/FAM50B genetic interaction. RKO and RKO-F50B+ (complemented with a FAM50B cDNA) were transduced with a lentivirus containing a doxycycline-inducible gRNA against FAM50A (see Methods). The cells also constitutively expressed Cas9 protein. Cells were seeded at 1000 cells/well; doxycycline (Dox; 0.1 µg/ml)/DMSO was added at 24 h. Cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet 9 days post seeding. This experiment is representative of three independent biological replicates.

Fitness effect of the FAM50A/FAM50B genetic interaction

We first sought to validate the FAM50A/FAM50B genetic interaction computationally using an independent data set34. Referencing whole-genome CRISPR screening data against cell line expression data suggested a significant dependency on FAM50A in cell lines with low or no FAM50B expression (TPM < 1; p < 2.2 × 10−16, Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon Test) (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Data 8). We next generated isogenic knockout or isogenic “rescued” cell lines for in vitro experiments. First, using the A375 cell line, which constitutively expresses both FAM50A and FAM50B, we created a FAM50B knockout clone using CRISPR-Cas9 (Supplementary Fig. 11). Consequently, through use of a competitive growth assay, we found a dependency of this line on FAM50A (Fig. 3C and Source Data). We next took two cell lines (RKO [colorectal] and TOV21G [ovarian]) where FAM50B was methylated and not expressed and used lentiviral transduction to introduce a FAM50B cDNA construct, showing that FAM50B expression (F50B+) rescued the lethal phenotype associated with FAM50A disruption (Fig. 3C). To further assess this relationship, we performed clonogenic survival assays (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 12) in RKO cells engineered to carry a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible FAM50A gRNA further validating the FAM50A/FAM50B interaction. Thus, we have validated the genetic interaction between FAM50A/FAM50B using an orthogonal data set, by using isogenic FAM50B knockout cells, cell lines that had lost FAM50B expression during their evolution, and also by genetic rescue in a range of cell line models.

Of note, in our CRISPR screens we observed that inactivation of FAM50A alone (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Data 1) was associated with an apparent loss of cellular fitness, despite the fact that we could readily derive FAM50A knockout clones (Supplementary Fig. 11). As a therapeutic target this might suggest that inhibition of FAM50A could have limiting toxicity. In this regard, we recently reported a new developmental syndrome (Armfield syndrome) associated with germline hypomorphic alleles of FAM50A where patients developed to adulthood with phenotypes including developmental delay39. This observation suggests a therapeutic window for FAM50A inhibition. Notably, although we observed the interaction of FAM50A/FAM50B in all cell lines screened, many genetic interactions are highly context dependent and influenced by both the genetics of the cell line and the growth environment. Thus, further studies will be required to establish all contexts in which the FAM50A/FAM50B interaction is operative.

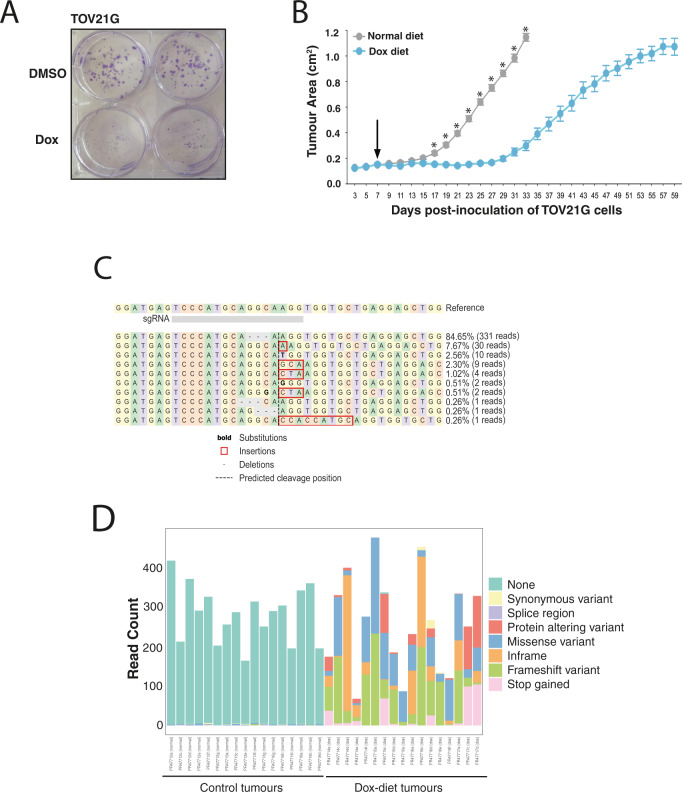

Targeting the FAM50A/FAM50B interaction in vivo

Not all fitness effects of gene disruption identified in culture can be replicated in vivo. To assess the possibility of targeting FAM50A in tumours that have lost FAM50B expression we used the TOV21G cell line carrying the Dox-inducible FAM50A gRNA construct mentioned above (see Methods). As shown in Fig. 3C and 4A, disruption of FAM50A in TOV21G cells precipitated a profound reduction in cellular fitness. Mice xenografted with the Dox-inducible line and fed a Dox-containing diet (0.625 g/kg; ENVIGO) exhibited a significant decrease in tumour growth compared with controls on a Dox-free diet (Fig. 4B and Source Data). We noted that after ~30 days, xenografts in which FAM50A had been disrupted by administration of the Dox diet appeared to regrow (Fig. 4B). To functionally assess the mechanisms of resistance, we sequenced the transcriptomes of a collection of 34 tumours: 17 tumours from Dox-fed mice and 17 control tumours from mice fed normal chow. This analysis revealed that all tumours that regrew on Dox treatment and were collected at the ethical endpoint (1.2 cm2) showed CRISPR editing at the gRNA cut site. These edits included in-frame events, which presumably were not disruptive of FAM50A but altered the cut site such that it was no longer a substrate for the gRNA, non-disruptive missense mutations and null alleles (nonsense and frameshift mutations). Wildtype traces, representing unedited alleles, were <1% of sequence reads (Fig. 4C, D). Thus, despite efficient editing at the gRNA binding site all resistant tumours were predicted to have retained some FAM50A activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that the genetic interaction between FAM50A/FAM50B robustly extends to the in vivo setting.

Fig. 4. Effect of FAM50A loss on TOV21G cell growth in vivo and mechanisms of resistance.

A Conditional disruption of FAM50A in FAM50B non-expressing TOV21G cells engineered (see Methods) to contain a dox-inducible FAM50A gRNA. B In vivo consequence of disrupting FAM50A in TOV21G cells on tumour growth. Data points represent the mean and SEM (see Methods). Dox diet was administered at the day 7 timepoint (arrow). Significance was defined using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney test by comparing the area under the curve for tumour growth in the Dox-fed and control groups. *p < 0.0001. These data are representative of two independent experiments. C An example of the FAM50A gRNA cut site showing the profile of editing events in a doxycycline (Dox)-treated tumour after regrowth. D Editing outcomes at the FAM50A gRNA cut site in tumours collected from untreated (left) and Dox-fed mice (right). The editing events were annotated using the Variant Effect Predictor (Ensembl). The Y axis is read depth/count.

Loss of FAM50A/FAM50B perturbs transcriptional programmes

FAM50A and FAM50B are proteins with as-yet-undefined roles. With the exception of N-terminal coiled-coil domains they lack other recognisable sequence or structural features40 (Supplementary Fig. 13). FAM50A and FAM50B have 74% DNA and 74.6% amino-acid sequence homology and are highly conserved throughout evolution. Notably, in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Schizosaccharomyces pombe orthologues of these genes have been postulated to be transcription factors or chromatin regulatory genes40,41, whereas in human cells both FAM50A and FAM50B have been shown to interact with the C complex of the spliceosome42,43 and via a high-throughput RNA-protein cross-linking approach, have been identified as candidate RNA-binding proteins44.

In order to assess transcriptomic changes associated with loss of FAM50A/FAM50B, we transcriptome profiled the effect of FAM50A knockout on two independent FAM50B null-isogenic cell line models. Using the TOV21G cell line (constitutively lacking FAM50B expression) or a CRISPR engineered FAM50B null A375 clone (A375-F50B−), we introduced a lentiviral vector carrying a gRNA to disrupt either FAM50A or a non-essential gene (AIPL1) and cultured the cells for 8 days prior to transcriptome sequencing. In both cell lines, gene set enrichment analysis revealed that disruption of FAM50A on a FAM50B null background resulted in statistically significant (padj < 0.05) transcriptional changes that included genes of the TP53 and TNFα/NFκβ pathways, and apoptosis regulators (Supplementary Fig. 14). As a comparator we also expression profiled FAM50A (F50A−) and FAM50B (F50B−) knockout A375 cells relative to parental A375 cells revealing some pathway overlaps (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Cellular phenotypes associated with FAM50A/FAM50B loss

Following an assessment of RKO cells in culture for phenotypes associated with FAM50A/FAM50B loss, we noted a marked increase in micronuclei, a phenotype that was rescued via the introduction of the FAM50B cDNA (F50B+) (Fig. 5A, B, Source Data). We also observed enhanced micronucleus production in A375-F50B- cells transduced with a lenti-FAM50A gRNA compared with transduced A375 (wildtype), where loss of FAM50A/FAM50B also caused an induction of apoptotic cell death (Fig. 5A–C, and Source Data). Thus, loss of FAM50A/FAM50B causes widespread alterations in normal cellular gene expression programmes alongside micronucleation, apoptosis, and cell death.

Fig. 5. Disruption of FAM50A/FAM50B results in micronucleus formation and apoptosis.

A Micronucleus levels in wildtype (WT), FAM50A null (F50A−) or FAM50B null (F50B−) A375 cells and WT or FAM50B-complemented (F50B+) RKO cells (left panel). Co-disruption of FAM50A/FAM50B results in a profound increase in micronucleus levels that can be rescued by FAM50B (F50B+) cDNA complementation (right panel). Cells were collected for analysis 7 days after transduction. The experiment performed on three separate occasions. B Representative images of micronuclei in A375 cell lines from the experiment in A. Scale bar represents 10 μM. C Analysis of apoptosis at day 7–8 using the CaspGlow assay (see Methods) in A375 cells and isogenic FAM50A (F50A−) or FAM50B (F50B−) knockout derivative lines. Early apoptosis: CaspGLOW positive/viable. Late apoptosis: CaspGLOW positive/non-viable. End apoptosis or necrosis: CaspGLOW negative/non-viable. Experiments were performed on three separate occasions in triplicate. For all panels error bars represent the mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM). p values were calculated using the unpaired two-tailed t test. ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Understanding the genetic wiring of cancer cells provides opportunities to identify tumour-specific vulnerabilities that might be exploited clinically. In this study, we screened >1100 gene pairs to identify 27 that were SL in multiple cell lines, several of which we confirmed with additional validation. Intriguingly, all nine of the gene pairs identified in all cell lines screened were paralogues and paralogue pairs were significantly enriched in the collection of SL interactions we identified. This suggests that, compared with the other gene sets we analysed, which included those defined by mutual exclusivity modelling of cancer data, paralogous genes are of high value for defining synthetic lethal interactions and candidate therapeutic targets. As there are multiple agents on the market that inhibit paralogues, such as trametinib (MEK1, MEK2) and PARP inhibitors (PARP1, PARP2), each of the 27 gene pairs we identified could be considered as targets for therapy development if follow-up studies can identify selectivity for cancer cells. Another way of using essential gene pair data is to identify situations where one member of the pair is lost somatically, thus exposing the other member of the pair as a candidate drug target and the data we have generated here could be mined for this purpose.

Of note, using TCGA expression data and referencing our collection of 27 recurrent SL gene pairs, we determined that FAM50B was silenced in a significant proportion of tumours across a range of histologies; 0–10% in each tumour type examined. Further, we showed that co-disruption of FAM50A and FAM50B both in vitro and in vivo precipitates a profound reduction in tumour cell fitness, a phenotype that could be partially rescued by reintroduction of FAM50B. Importantly, we observed dysregulation of a range of cell regulatory transcriptional programmes and the formation of extensive micronuclei together with apoptotic cell death, suggesting a specific role for FAM50A/FAM50B in cellular survival via maintenance of genome stability. In agreement with our study, Dede et al.45 recently identified FAM50A/FAM50B as a candidate SL gene pair in cancer cell lines. Our screen is one of the first to profile gene paralogues as potential drug targets at scale and thus represents a blueprint for endeavours to prioritise all genes for screening.

Methods

Library construction and lentiviral production

The CRISPR gRNA library was constructed using the method previously described by Vidigal and Ventura31. A detailed protocol is available at Protocols.io (dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.bpqhmmt6). The gRNAs used are provided in Supplementary Data 2 and 4. In brief, using the ENSEMBL annotation v79 of the GRCh38 version of the human reference genome we identified targeting sites in the form of 5′-NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNGG-3′, which were filtered to remove sequences that were non-unique and off-target sites using WGE46. Subsequently, using the ENSEMBL Perl API v84, we identified those gRNAs whose cutting sites were located within a protein domain as reported by Pfam and then discarded sequences containing BbsI restriction sites. From the resulting set of gRNAs we selected 3–5 per gene to be included in the library. Each of these gRNAs were paired with each of the 3–5 gRNAs designed for the other gene in the pair. gRNAs were also individually paired with a non-targeting Fluc_gRNA control (GTGTTGGGCGCGTTATTTATCGG) from the Firefly (Photinus pyralis) luciferase gene to allow assessment of single gene lethality. Single-targeting guides were always under the sU6 promoter (with the non-targeting gRNA under the hU6 promoter). Combinatorial guides were in a single orientation (eg hU6 guide_A + sU6 guide_B). The final library contained 41,838 different combinations of gRNAs including gRNAs targeting a total of 1191 gene pairs, 12,803 gRNAs combined with the Fluc_gRNA control and gRNAs against essential/non-essential genes to aid in statistical analysis. To make virus, 20 × 106 293 T cells were transfected with 11.25 μg pMD2.G (Addgene #12259), 17 μg psPAX2 (Addgene #12260) and 22.5 μg of dual gRNA library plasmid. Media was changed 12 h post transduction and virus was harvested 36 h later and stored at −80 °C.

Cell line culture and screening

All cells were cultured at 37 °C/5%CO2 in media as specified by ATCC. Cell line identity was confirmed by STR profiling and all cells were screened and found negative for mycoplasma. Cas9-expressing cell line generation was performed using a lentivirus produced with the pKLV2EF1a-Cas9Bsd-W plasmid (Addgene, #68343). The activity was confirmed with a BFP/GFP reporter assay32. All lines had ≥90% Cas9 activity prior to screening (Supplementary Fig. 2). CD15/CD33 validation experiments in Molm-13 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1) were performed using CD15-APC and CD33-PE antibodies from Miltenyi (1:5 dilution for both). The combinatorial CRISPR library was titered using cellular survival in puromycin. Library infections for screening were performed in triplicate at an MOI of 0.3, at a library representation of 1000×. Puromycin selection (2 µg/ml for A375, MeWo and 15 µg/ml for RPE-1) was continued from day 3–7 post transduction. Cells were maintained throughout the screen at a minimum representation of 3000x. Sequencing was performed on DNA extracted from these cell cultures at timepoints 14 and 28 days post transduction. As a control, wildtype A375 cells (Cas9-negative) were transduced with the library under conditions matching the screening conditions and harvested at day 7.

Sequencing protocol

DNA extraction was performed using a Blood & Cell Culture DNA Maxi Kit (Qiagen). For each replicate, 48× PCRs containing 3 µg genomic DNA were performed using KAPA HiFi Polymerase (ThermoFisher), using the primers listed in Supplementary Data 2. The PCRs were pooled and cleaned up with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and SPRI beads (Beckman). The amplicon was then diluted to 40 pg/µl and a second round PCR was performed to add indexing primers (Illumina), using 8–10 cycles aiming for a final concentration of 4 ng/µl. The amplicon was again purified with SPRI select. The final sequencing was performed to a depth of 500-fold representation/sample, using a customised two-forward read sequencing strategy with the primers listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Analysis of the paired library output

We used the Bliss independence model35 to define synergy between gRNA pairs using the equation:

| 1 |

Note, g1g2 represents the paired gRNA construct, targeting two genes, and g1 and g2 represent each of these guides when paired with a non-targeting (Fluc) control. In this equation, the synthetic lethality/fitness effect is the difference between the log2FC of the pair observed in the screen and log2FC expected by the model. We performed both the control and experimental replicates in triplicate, therefore comparing each experimental replicate to each control resulted in nine comparisons per construct. For each of these nine comparisons, we plotted observed vs predicted effects, and using Loess regression, the behaviour of the population was modelled. Population modelling in this way accounts for the effect of CRISPR-mediated cutting of the genome and the potential effect of single vs double cutting. For each paired gRNA construct, a residual (vertical distance from the modelled line) was interpolated. The variance of residuals was found to be heteroscedastic, with greater variance observed when the expected effect of the guide pair was more lethal. To correct for this heteroscedasticity, variance smoothing was performed19. This was done by ranking each g1g2 construct by the expected fold change; the residuals were then put into bins of 200 (arbitrary number) and the variance of each bin calculated. The value of each residual was then divided by the variance of the bin that it belonged to so as to create a variance adjusted residual, resulting in equal variance across the model. For each gene pair, we then generated up to 225 (25 × 9) independent residuals from each of the gRNA paired constructs.

To derive ‘hits’ from the screen we required significance in two independent statistical tests; a t test and the robust ranking algorithm (RRA). Gene pairs typically detected in only the RRA analysis often had a single guide producing a large residual, with the remaining constructs having minimal biological effect and a mean effect close to zero. Given that in these cases, the significance of the pair was often driven by a single guide, possibly driven by off-target effects, we did not wish to consider these pairs as hits. Gene pairs typically detected in only the t test had a minor global negative shift, with few guide pairs ranking in the bottom 10% of residuals. Given that we were interested in pairs which had a large biological effect (favouring the RRA), but did not want to select genes where a single guide was causing outliers (favouring the t test) we chose to take the overlap between the two analyses to ensure size and consistency of effect.

For the t test the equation used was:

| 2 |

Robust ranking was performed as detailed previously33 using the bottom 10% of residual values. For each test (t test or RRA) we used a Bonferroni test to correct for multiple testing and counted as significant pairs with an FDR < 0.1.

Filtering candidate genetic interactions

We noted that lethal gRNAs defined by either MAGeCK or BAGEL29,30 analysis of the single gene targeting constructs (i.e., gRNAs paired with a non-targeting gRNA), when put under the hU6 promoter in a gene pair, were more likely to produce a significant residual (p < 2.2 × 10−6, Fisher exact test). This is likely due to enhanced gRNA activity in this context. In view of this, we did not consider any pairs containing genes lethal in isolation as screen hits. Genes were considered lethal if BAGEL or MAGeCK detected them as lethal in our screen at day 14, or in an independent screen34 (using an FDR < 0.1 for MAGeCK and a PPV < 5% for BAGEL).

Validation of candidate SL interactions

Genetic interactions were validated using the technique established previously19. In total, eight pairs underwent low-throughput validation, with three additional non-interacting pairs used as controls (AIPL1/ACCSL, AIPL1/ASF1B, TTC7A/ACCSL). Guides showing activity across all cell lines were chosen for the validation (Supplementary Data 4) and cloned into the lentiviral pKLV2-U6gRNA5(BbsI)-PGKpuro vector backbone expressing either BFP or mCherry (Addgene #67974 or #67977). Cells were transduced in triplicate to create four populations (Fig. 2A) and the abundance of each population was read at day 4 and day 14 by FACS. Analysis was performed with FlowJo (v10.4.2) and graphs drawn with GraphPad v7.04 & v8.4.3 and R (3.6.3).

Construction of isogenic cell lines

To generate knockout clones, the A375-Cas9 cell line was transduced with a lentivirus containing a gRNA against FAM50A or FAM50B at single copy (Supplementary Data 2). Cells were selected with puromycin then single cells sorted by FACS into 96-well plates. Clones were expanded, and the editing site was Sanger sequenced to confirm editing. Clones chosen for further studies carried frameshift mutations (Supplementary Fig. 11). The FAM50A knockout clone was further confirmed by western Blot analysis (Supplementary Fig. 11) using and anti-FAM50A antibody (ABCAM, Rabbit monoclonal (ab186410) 1:3000 dilution). An anti-vinculin antibody from Sigma (SAB4200080) was used as a loading control (1:3000 dilution). An antibody for FAM50B is not available. Both FAM50A and FAM50B clones were also validated by visual inspection of transcriptome sequence data generated as described below.

Two cell lines (RKO-Cas9 and TOV21G-Cas9) lacking FAM50B expression based on RNAseq data34 were selected for rescue/complementation experiments. A lentivirus containing a full-length FAM50B cDNA was produced (Myc-DDK tagged; Origene; RC201531L3) and overexpression of FAM50B confirmed by western blotting (Myc tag 05-724 [clone 4A6]; Millipore, 1:2000 dilution). To create inducible knockouts, a gRNA against FAM50A (Supplementary Data 2) was cloned into the CRISPR pRSGTEBleo-U6Tet-(xx)-EF1-TetRep-2A-Bleo backbone (Cellecta) following the manufacturer’s instructions and correct assembly confirmed by Sanger sequencing. This vector was transduced into RKO-Cas9 and TOV21G-Cas9 cells. Five days after transduction cells were single cell sorted into 96-well plates, and one week post sorting 200 µg/ml zeocin was added to the media for 3 weeks to identify resistant clones.

Clonogenic assays

Cells were seeded into six-well plates at 1000 cells/well. 24 h post seeding, media was changed to either contain doxycycline (0.1 µg/ml) or an equivalent volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The assay was terminated as cells in the control (DMSO) wells approached confluence. Cells were fixed with 100% ice-cold methanol and stained with 1% crystal violet solution.

Apoptosis assays

The CaspGlow assay (ThermoFisher) was used to assess apoptosis at day 7/8 after viral transduction as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNASeq analysis

To assess the transcriptional effect of co-disruption of FAM50A and FAM50B, A375 FAM50B cells (A375-F50B−) and TOV21G cells were seeded at 500,000 cells per well in six-well plates with 8 µg/ml polybrene, and transduced with either the BFP-F50A_gRNA lentivirus or the BFP-AIPL1_gRNA lentivirus to infect >90% of cells. Media was changed at 24 h and cells were maintained in culture until harvest (day 7–8). The experiment was performed as three independent transductions per condition. RNA extraction was performed with the Direct-zol RNA microprep (Zymo research; R2060) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Library preparation was performed using the KAPA stranded RNAseq kit using RiboErase. Samples were multiplexed and sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 with 75 bp paired-end reads. Sequences were pseudo-aligned to the Homo Sapiens transcriptome and quantified using the Kallisto quantifier47 (v 0.44.0). We ran DESeq248 on the gene-level counts, first removing all genes with low-level counts. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed with fgsea (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/fgsea.html).

In vivo assessment of FAM50A essentiality in TOV21G xenografts

For examination of primary tumour growth, NOD-SCID mice at 6–8 weeks of age were subcutaneously administered 2.5 × 106 TOV21G- iF50A clone 9 cells (in 0.1 mL phosphate-buffered saline; PBS) in the right flank. The mice were fed Mouse Breeders Diet (Laboratory Diets, 5021-3) and one week after dosing were randomly assigned into two cohorts with one being fed a Doxycycline diet (Dox; 625 mg/kg; Envigo, TD.01306) and the other remaining on the Mouse Breeders Diet for the remainder of the study. The developing tumours were measured every second day until they reached 1.2 cm2 (calculated by: longest length measurement × longest width measurement), at which point animals were humanely sacrificed and the mass excised and stored at −80 °C. The care of mice in this study and all experimental procedures was in accordance with Home Office guidelines (P6B8058BO). Procedures were further approved by the Animal Welfare Ethical Review Body (AWERB) of the Welcome Trust Sanger Institute. Housing and husbandry conditions were exactly as detailed previously49. The experiment was independently replicated twice. The first cohort were female mice and the second cohort were male.

Micronucleus assay

To count micronuclei, cells were grown on coverslips, then at the time of the assay, coverslips were washed once with PBS then fixed with three parts ethanol/1 part acetic acid for one minute. Coverslips were then washed twice with PBS before mounting onto microscope slides with Vectashield DAPI mounting medium (Vector Labs). Micronuclei were counted on a Leica microscope, selecting random fields and counting all nuclei and micronuclei in each field until >500 nuclei had been counted.

All mouse experiments were performed under Home Office Project Licence P6B8058BO with ethics board approval.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

N.T. was funded by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute Clinical PhD Programme. This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (206194) and by grants to DJA from Cancer Research UK and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC synergy grant agreement no. 319661 COMBATCANCER. Research in the SPJ lab was supported by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant (C6/A18796), a Wellcome Investigator Award (206388/Z/17/Z), by Gurdon Institute Core Funding from Cancer Research UK (C6946/A24843), the Wellcome Trust (WT203144) and by the ERC Synergy Grant 855741 (DDREAMM). S.P.J. receives salary support from the University of Cambridge. Research in the MJG laboratory was supported by the Wellcome Trust and Open Targets. We thank Daniela Robles for help with artwork and the Sanger Institute flow cytometry core.

Source data

Author contributions

N.A.T. and D.J.A. conceived the experiments. The majority of the experimental work was performed by N.A.T. with help from G.Z.V., M.R., A.D., A.S., F.B., J.H., E.A., B.F., L.S., S.S.M.E., F.Y., L.v.d.W., J.C., V.H., H.R., K.W., M.P.C. and M.G. S.P.J., E.G., F.I., V.I., P.C., V.O. and M.d.C.V. performed the analysis.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data are available for download from the European Genome-Phenome Archive: CRISPR data: EGAD00001006648 and RNAseq data: EGAD00001006649. All other data can be found in the Supplementary Data of this paper or in the Source Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All of the code used in the paper was from published studies and is cited in the manuscript. Version numbers are provided in the Reporting Summary.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Ophir Shalem and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Marco Ranzani, Louise van der Weyden.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21478-9.

References

- 1.Nijman SM. Synthetic lethality: general principles, utility and detection using genetic screens in human cells. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashworth A, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: what’s next after PARP inhibitors? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:564–576. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer H, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science. 2017;355:1152–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan CJ, Bajrami I, Lord CJ. Synthetic lethality and cancer - penetrance as the major barrier. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Zee JP, et al. Paralog analyses reveal gene duplication events and genes under positive selection in Ixodes scapularis and other ixodid ticks. BMC genomics. 2016;17:241. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2350-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnhammer ELL, Koonin EV. Orthology, paralogy and proposed classification for paralog subtypes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:619–620. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Kegel B, Ryan CJ. Paralog buffering contributes to the variable essentiality of genes in cancer cell lines. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald ER, 3rd, et al. Project DRIVE: a compendium of cancer dependencies and synthetic lethal relationships uncovered by large-scale, deep RNAi screening. Cell. 2017;170:577–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato E, et al. ARID1B as a potential therapeutic target for ARID1A-mutant ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1710. doi: 10.3390/ijms19061710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jelinic P, et al. Concomitant loss of SMARCA2 and SMARCA4 expression in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. Mod. Pathol. 2016;29:60–66. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman GR, et al. Functional epigenetics approach identifies BRM/SMARCA2 as a critical synthetic lethal target in BRG1-deficient cancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2014;111:3128–3133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316793111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lord, C. J., Quinn, N. & Ryan, C. J. Integrative analysis of large-scale loss-of-function screens identifies robust cancer-associated genetic interactions. Elife9, e58925 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Roller DG, et al. Synthetic lethal screening with small-molecule inhibitors provides a pathway to rational combination therapies for melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2505–2515. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Z, et al. Chemical genetic screening of KRAS-based synthetic lethal inhibitors for pancreatic cancer. Front. Biosci. 2009;14:2904–2910. doi: 10.2741/3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berns K, et al. A large-scale RNAi screen in human cells identifies new components of the p53 pathway. Nature. 2004;428:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nature02371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsherniak A, et al. Defining a cancer dependency map. Cell. 2017;170:564–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yau EH, et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen for essential cell growth mediators in mutant KRAS colorectal cancers. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6330–6339. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han K, et al. Synergistic drug combinations for cancer identified in a CRISPR screen for pairwise genetic interactions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:463–474. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen JP, et al. Combinatorial CRISPR - Cas9 screens for de novo mapping of genetic interactions. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:573–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Najm FJ, et al. Orthologous CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes for combinatorial genetic screens. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;36:179–189. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T, et al. Genetic interaction mapping and exon-resolution functional genomics with a hybrid Cas9-Cas12a platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:638–648. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow RD, et al. In vivo profiling of metastatic double knockouts through CRISPR-Cpf1 screens. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:405–408. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo Y, et al. Network-based combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 screens identify synergistic modules in human cells. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019;8:482–490. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wappett M, et al. Multi-omic measurement of mutually exclusive loss-of-function enriches for candidate synthetic lethal gene pairs. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:65. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2375-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu X, Megchelenbrink W, Notebaart RA, Huynen MA. Predicting human genetic interactions from cancer genome evolution. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo J, Liu H, Zheng J. SynLethDB: synthetic lethality database toward discovery of selective and sensitive anticancer drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1011–D1017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waddell N, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hart T, Moffat J. BAGEL: a computational framework for identifying essential genes from pooled library screens. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016;17:164. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-1015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hart T, et al. Evaluation and design of genome-wide CRISPR/SpCas9 knockout screens. G3 (Bethesda) 2017;7:2719–2727. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidigal JA, Ventura A. Rapid and efficient one-step generation of paired gRNA CRISPR-Cas9 libraries. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8083. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tzelepis K, et al. A CRISPR dropout screen identifies genetic vulnerabilities and therapeutic targets in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W, et al. MAGeCK enables robust identification of essential genes from genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol. 2014;15:554. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0554-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Behan FM, et al. Prioritization of cancer therapeutic targets using CRISPR–Cas9 screens. Nature. 2019;568:511–516. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foucquier J, Guedj M. Analysis of drug combinations: current methodological landscape. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2015;3:e00149. doi: 10.1002/prp2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahman M, et al. Alternative preprocessing of RNA-Sequencing data in The Cancer Genome Atlas leads to improved analysis results. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3666–3672. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakabayashi K, et al. Methylation screening of reciprocal genome-wide UPDs identifies novel human-specific imprinted genes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:3188–3197. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Trujillo A, et al. Copy number rather than epigenetic alterations are the major dictator of imprinted methylation in tumors. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:467. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00639-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee, Y.-R. Mutations in FAM50A cause Armfield XLID syndrome: a spliceosomopathy impacting neurodevelopment. Nat. Commun.11, 3698 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Anver S, et al. Yeast X-chromosome-associated protein 5 (Xap5) functions with H2A.Z to suppress aberrant transcripts. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:894–902. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li L, et al. New class of transcription factors controls flagellar assembly by recruiting RNA polymerase II in Chlamydomonas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:4435–4440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719206115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bessonov S, Anokhina M, Will CL, Urlaub H, Lührmann R. Isolation of an active step I spliceosome and composition of its RNP core. Nature. 2008;452:846–850. doi: 10.1038/nature06842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agafonov DE, et al. Semiquantitative proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome via a novel two-dimensional gel electrophoresis method. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;31:2667–2682. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05266-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castello A, et al. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell. 2012;149:1393–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dede, M. et al. Multiplex enCas12a screens detect functional buffering among paralogs otherwise masked in monogenic Cas9 knockout screens. Genome Biol.21, 262 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Hodgkins A, et al. WGE: a CRISPR database for genome engineering. Bioinformatics (Oxf., Engl.) 2015;31:3078–3080. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–527. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Weyden L, et al. Genome-wide in vivo screen identifies novel host regulators of metastatic colonization. Nature. 2017;541:233–236. doi: 10.1038/nature20792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data are available for download from the European Genome-Phenome Archive: CRISPR data: EGAD00001006648 and RNAseq data: EGAD00001006649. All other data can be found in the Supplementary Data of this paper or in the Source Data. Source data are provided with this paper.

All of the code used in the paper was from published studies and is cited in the manuscript. Version numbers are provided in the Reporting Summary.