Early in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, fears of viral transmission to health care workers prompted institutions around the world to reassess timing and technique for performing tracheostomies. There was great hesitance to perform tracheostomies during the first wave of the pandemic, evident in a study spanning 26 countries, in which of more than 90% of protocols and practices involved deferral beyond 14 days.1 Fortunately, we have learned a lot over the last 9 months.

A growing body of evidence documents the safety and benefit of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients, provided appropriate precautions are taken.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Early tracheostomy accelerates weaning from the ventilator and may have a critical role in freeing up ventilators, ICU beds, and staff during surges.4 This consideration is important, because resource scarcity may limit access to life-saving interventions for other patients.7 We argue that tracheostomy before 14 days has a role in a select group of patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Sizing Up the Enemy: What Makes COVID-19 Different?

Early reports described COVID-19 ARDS (CARDS) as a unique entity.8 COVID-19 patients purportedly had unusually high lung compliance and poorer oxygenation; yet, comparison of COVID-19 ARDS data with those of earlier ARDS trials reveals only minimal differences.9 Favorable response to prone ventilation mirrors historical ARDS data.10 Pulmonary microthrombosis and alveolar damage in COVID-19 has also attracted interest—findings also documented in ARDS more than 3 decades ago9; thus, if a distinct CARDS phenotype exists, it is yet to be proven.

Misconceptions about COVID-19 have likely been an impediment to maximizing benefit from tracheostomy. For example, the early misconception that patients with COVID-19 would declare themselves swiftly—by recovering or succumbing to disease within 2 to 3 weeks—made tracheostomy seem pointless. As with all ARDS patients, the course is variable and quite difficult to predict. ARDS is not a single disease, but rather a syndrome,11 and indications for tracheostomy in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure are no different from those in other patients with respiratory failure.

Early Tracheostomy vs Prolonged Intubation in Patients With COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Failure

The foremost consideration regarding tracheostomy is not timing but whether the procedure is indicated. Critically ill patients requiring invasive ventilation have up to 50% mortality.12 Tracheostomy should occur only after there are signs of improvement, because performing the procedure in patients with grim prognosis offers no benefit and exposes staff to unnecessary aerosol-generating procedures.4 Delaying tracheostomy may reduce the risk to health care workers because the viral load of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may be lower, but that reduction in risk must be weighed against prolonged intubation.13 Additionally, there have not been any reports of increased risk to health care workers associated with tracheostomy as long as adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) is used.

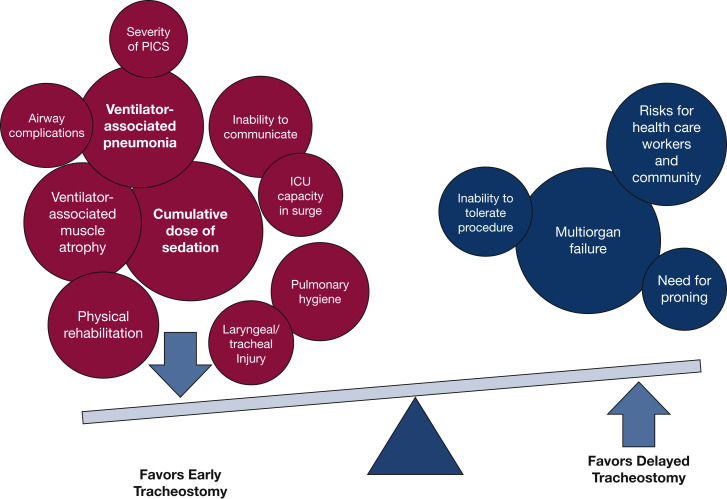

The patient must demonstrate physiological reserve to tolerate the procedure. Most tracheostomy techniques in the COVID-19 era involve a pause in ventilation with loss of peak end-expiratory pressure, risking de-recruitment. Furthermore, tracheostomy should not be performed in a patient requiring prone ventilation, because of the heightened risk of accidental decannulation, displacement, occlusion, or other device-related complications that are less readily identified and managed in the prone position.13 Therefore, we suggest that established principles regarding indications and candidacy should take precedence over considerations of timing (Fig 1 ).

Figure 1.

Factors influencing timing for tracheostomy. For most patients with COVID-19 who show evidence of improvement and need for prolonged mechanical ventilation, the preponderance of benefit favors early tracheostomy on a timeline consistent with established critical care practices. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Benefits of Performing Tracheostomy in COVID-19 Patients Requiring Prolonged Ventilation

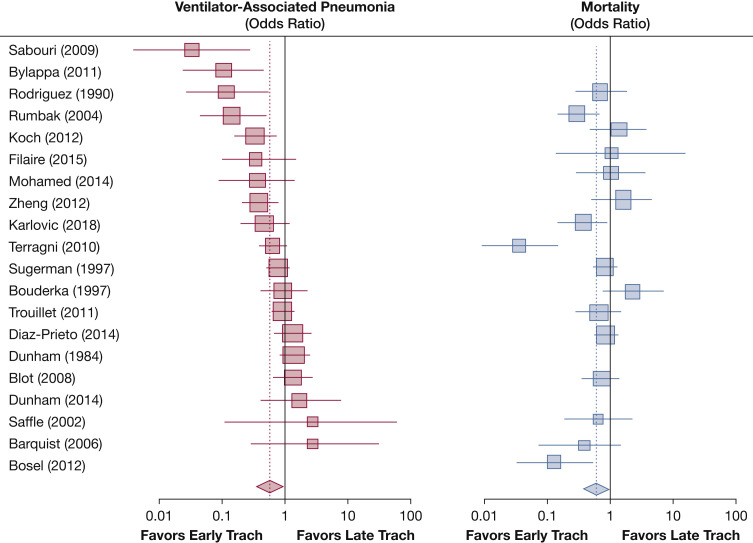

Numerous randomized trials attest to benefits of early tracheostomy in appropriately selected patients. Tracheostomy reduces the cumulative sedation dose14 and allows for earlier participation in physical therapy and rehabilitation; this improvement in early mobility lessens the risk of critical illness myopathy and VTE. Early tracheostomy is also associated with earlier walking, talking, and eating.15 Earlier extubation lowers the risk of airway complications arising from prolonged translaryngeal intubation, such as focal tracheomalacia and tracheal stenosis (Fig 2 ).

Figure 2.

Comparison of early vs late (or no) tracheostomy. The figure summarizes the trend of studies evaluating early vs late tracheostomy on ventilator-associated pneumonia and mortality. Although early vs late was most commonly defined at 10 days, the range spanned from 3 days to 14 days, and data representation is approximate. (Full references for studies are available in e-Appendix 1).

COVID-19 Tracheostomies and Infection Risks for Health Care Workers

Predicted high rates of infection in health care workers performing tracheostomy have not been reported. Colleagues at New York University reported 98 COVID-19 tracheostomy procedures at a median 10.6 days from intubation, with no team members testing positive for SARS-CoV-2,2 as did subsequent reports.3 , 5 Reluctance to perform tracheostomy is gradually being replaced by an approach in which the primary considerations are patient-centered outcomes along with proper safety measures with PPE and modified techniques to minimize aerosol generation.

Enhanced PPE, standardized donning/doffing protocols, and modified tracheostomy techniques all may minimize risk; however, other factors also may contribute to lower than expected transmission with tracheostomy. SARS-CoV-2 infectivity peaks 3 to 4 days after infection, whereas a tracheostomy after 10 days of intubation may be 2 weeks out from initial infection, once infectivity has diminished.4 COVID-19 test results from patients often detect inert viral RNA, which can be amplified by polymerase chain reaction, long after virus is nonviable in culture and hence noninfectious.16 Finally, SARS-CoV-2 viral loads are highest in upper respiratory tract mucosa, particularly the nasopharynx,17 whereas viral loads for SARS-CoV, the virus responsible for SARS outbreaks, were highest in the lower respiratory tract.16

Going Beyond the Procedure: Post-tracheostomy Care in COVID-19 Patients

Another challenge in caring for patients with COVID-19 is disposition after tracheostomy. The tracheostoma creates an open source of aerosolization and necessitates suctioning, change of tracheostomy tubes or inner cannulas, and other routine care. A multidisciplinary tracheostomy team consisting of interventional pulmonologists, otolaryngologists, nursing, speech-language pathology, and respiratory therapy ensures attentive care.13 Patients on a trach collar may be candidates for downsizing, capping, and decannulation.18

COVID-19-specific management and decannulation protocols are critical aspects of postoperative care. Long-term assisted care units and subacute rehabilitation facilities may be limited in their ability to accept patients after an ICU stay with COVID-19.

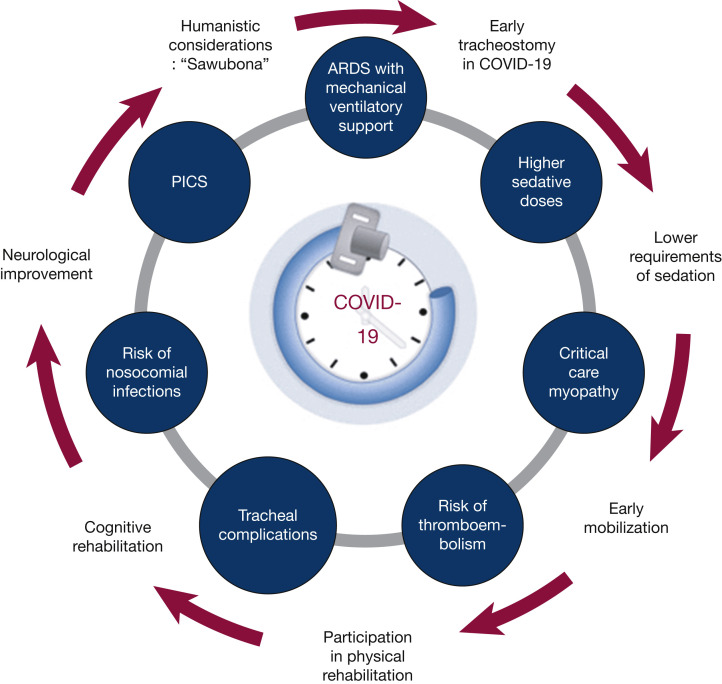

COVID-19 Survivorship and Humanism

COVID-19 survivorship may be associated with post-ICU syndrome (PICS), which encompasses physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments that may persist for months or years beyond hospital discharge.19 Prolonged translaryngeal endotracheal tube intubation and sedation predisposes to laryngotracheal injury, dysphagia, dysphonia, laryngo- tracheal stenosis, and diaphragmatic dysfunction.20 Minimizing the duration of sedation, translaryngeal intubation, and ICU stay with appropriate timing of tracheostomy may expedite recovery and decrease severity of PICS (Fig 3 ).

Figure 3.

COVID-19 survivorship and rationale for early timing of tracheostomy. COVID-19 survivorship entails morbidity that can span years because of post-intensive care syndrome (PICS). Early tracheostomy can liberate patients from the ventilator early, thereby reducing the severity of PICS. At the center of the image is a clock, encircled by a tracheostomy tube, symbolizing the central role that timeliness in tracheostomy plays in reducing time on ventilator and in the ICU. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Finally, humanistic considerations are integral to decision-making in the ICU. Clinicians taking care of patients with COVID-19 are all too familiar with how tubes, lines, and other ICU paraphernalia can render edematous faces unrecognizable. There is no more humanizing thing than to restore a face to sick patients; the emotional toll is ponderous for patients, families, and the health care team. The Zulu tribe greeting, “Sawubona” means “I see you” but also communicates, “You are important to me and I value you.” When we embrace this concept—make the other person visible—then we accept them and grant them dignity.

Conclusions

A virtue of the COVID-19 pandemic has been opening of our eyes to how much we have to learn, and a vice has been closing our eyes to what is known, from decades of data. Tracheostomy is a safe procedure that plays a vital role in management of COVID-19 patients with severe ARDS. Once prone positioning is no longer required, candidacy for tracheostomy may be assessed by a multidisciplinary team, preferably on a timeline similar to that for other ICU patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. We should treat every patient, COVID-19 positive or not, as an individual, with an eye toward honoring safety, humanity, and dignity.

Acknowledgments

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL/NONFINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: D. F.-K. received consulting fees from Cook Medical in 2019. None declared (M. J. B., J. D).

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This work was further supported by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research [Grant UL1TR002240] under the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Bier-Laning C., Cramer J.D., Roy S. Tracheostomy during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison of international perioperative care protocols and practices in 26 countries. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820961985. 194599820961985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel L., Kon Z.N., Chang S.H. Novel percutaneous tracheostomy for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110(3):1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao T.N., Braslow B.M., Martin N.D. Tracheotomy in ventilated patients with COVID-19. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):e30–e32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGrath B.A., Brenner M.J., Warrillow S.J. Tracheostomy in the COVID-19 era: global and multidisciplinary guidance. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):717–725. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30230-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham C-at Safety and 30-day outcomes of tracheostomy for COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(6):872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosano A., Martinelli E., Fusina F. Early percutaneous tracheostomy in coronavirus disease 2019: association with hospital mortality and factors associated with removal of tracheostomy tube at ICU discharge—a cohort study on 121 patients. Crit Care Med. 2021;49(2):261–270. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truog R.D., Mitchell C., Daley G.Q. The toughest triage: allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1973–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marini J.J., Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2329–2330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rose M.R., Hiltz K.A., Stephens R.S., Hager D.N. Novel viruses, old data, and basic principles: how to save lives and avoid harm amid the unknown. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):661–663. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30236-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerin C., Reignier J., Richard J.C. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Force A.D.T., Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meister K.D., Pandian V., Hillel A.T. Multidisciplinary safety recommendations after tracheostomy during COVID-19 pandemic: state of the art review [Published online ahead of print September 22, 2020] Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820961990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cagino L.M., Kercheval J.B., Kenes M.T. Association of tracheostomy with changes in sedation during COVID-19: a quality improvement evaluation at the University of Michigan [Published online ahead of print November 24, 2020] Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1096RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sutt A.L., Tronstad O., Barnett A.G., Kitchenman S., Fraser J.F. Earlier tracheostomy is associated with an earlier return to walking, talking, and eating. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez Martinez G., Rodriguez M.L., Vaquero M.C. High-flow oxygen with capping or suctioning for tracheostomy decannulation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1009–1017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2010834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosey M.M., Needham D.M. Survivorship after COVID-19 ICU stay. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):60. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiacchini G., Trico D., Ribechini A. Evaluation of the incidence and potential mechanisms of tracheal complications in patients with COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(1):70–76. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.