Abstract

Candida auris is a nosocomial pathogen responsible for an expanding global public health threat. This ascomycete yeast has been frequently isolated from hospital environments, representing a significant reservoir for transmission in healthcare settings. Here, we investigated the relationships among C. auris isolates from patients with chronic respiratory diseases admitted in a chest hospital and from their fomites, using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and multilocus microsatellite genotyping. Overall, 37.5% (n = 12/32) patients developed colonisation by C. auris including 9.3% of the screened patients that were colonised at the time of admission and 75% remained colonised till discharge. Furthermore, 10% of fomite samples contained C. auris in rooms about 8.5 days after C. auris colonised patients were admitted. WGS and microsatellite typing revealed that multiple strains contaminated the fomites and colonised different body sites of patients. Notably, 37% of C. auris isolates were resistant to amphotericin B but with no amino acid substitution in ERG2, ERG3, ERG5, and ERG6 as compared to the reference strain B8441 in any of our strains. In addition, 55% of C. auris isolates likely had two copies of the MDR1 gene. Our results suggest significant genetic and ecological diversities of C. auris in healthcare setting. The WGS and microsatellite genotyping methods provided complementary results in genotype identification.

Keywords: Candida auris, colonisation, microsatellite typing, whole genome sequencing, ERG11, TAC1B, amphotericin B resistance in C. auris, India

1. Introduction

Candida auris is a multidrug-resistant fungus that has been implicated in hospital-associated outbreaks of life-threatening invasive infections with high mortality. Since its first report in 2009, C. auris has caused major outbreaks in healthcare facilities in Colombia, India, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, South Africa, Spain, United Kingdom, United States, and Venezuela [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The predisposition of C. auris to colonise hospitalised patients and its potential for person-to-person spread from colonised and infected patients have raised concerns about further large-scale outbreaks in healthcare facilities [14] The other major concern in the nosocomial transmission is the propensity of shedding viable yeast cells from patients, thus contaminating environmental surfaces in rooms of colonised or infected patients. Remarkably, C. auris has been frequently recovered from common shared surfaces in the hospital environment, suggesting the potential risk of environmental transmission in healthcare settings [14,15]. Indeed, molecular epidemiology investigation has provided key insights into the origin and transmission of C. auris. However, the dynamics of transmission of C. auris in hospital settings using whole genome sequencing (WGS) have been analysed in limited studies, primarily from Colombia, the United Kingdom, and United States [10,11,14,16,17]. Specifically, WGS of C. auris isolates from patient contacts, healthcare workers, and the environment in 4 hospitals with C. auris outbreaks in Colombia revealed widespread environmental contamination and colonisation among patients and healthcare workers. Their study reported genetically identical isolates within hospitals that connected patients to environmental surfaces and healthcare workers [14]. In contrast, the genetic epidemiology of an outbreak of C. auris in a specialized cardiothoracic London hospital using MinION nanopore sequencing technology suggested that patients were infected with a genetically heterogeneous population [16]. Further, none of the patients and the hospital environment was infected with a single, clonally propagating C. auris strain. Interestingly, a C. auris outbreak in the neurosciences intensive care unit (ICU) of the Oxford University Hospital, United Kingdom was linked to reusable axillary temperature probes. WGS identified that isolates from reusable equipment were genetically related to patient isolates [11].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the genetic diversity and transmission dynamics of C. auris, colonising the patients with chronic respiratory diseases admitted in a referral chest hospital in Delhi, India and assessed the environmental contamination in rooms occupied by colonised patients. To understand the mode of spread between patients within the hospital, we performed WGS and evaluated the recently described microsatellite length polymorphism (MLP) typing using a short tandem repeats (STRs) assay for C. auris in the transmission of this yeast in clinical settings [18].

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

The study was approved by Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute (2019/2401).

Study Design

Patients with chronic respiratory diseases admitted to the medical ward during the six months period (December 2019–May 2020), were enrolled for screening of Candida auris. The study was conducted in 16 rooms of a medical ward housing 64 beds, primarily for patients with respiratory disorders, admitted for acute episodes or exacerbations of chronic diseases. Patients were screened at the day of hospitalisation by swabbing 4 sites (ear, nose, axilla, groin) individually for each patient. Blood cultures were collected from patients whose screening swabs yielded C. auris. Swab samples were repeated every week up to the day of discharge of the patients. Environmental sampling of all rooms with colonised patients was conducted at the time of patient contact and repeated every week when patients were sampled till discharge.

2.2. Collection and Processing of Clinical and Environmental Specimens

2.2.1. Collection of Swab Specimens

(i) Skin swabs: The swabs were collected individually from axilla, groin, nose, and ear of each patient using sterile cotton swabs premoistened in sterile physiological saline. Swabs were placed in capped propylene tubes (HIMEDIA, Mumbai, India) and were transported to the laboratory within an hour at ambient temperature.

(ii) Environmental swabs: The premoistened swabs were swept back and forth over an area of 25 cm for effective collection of samples [19]. Environment samples were collected from different sites near each patient’s bed including bed railing, bed sheet, pillow, bedside trolly, floor, and air conditioner air wings. Surface swabs were also collected from medical equipment (thermometer, B.P. cuffs, ECG clip and sucker, oxygen mask, and nebuliser) and portable devices (mobile, wheelchair, and intravenous pole). Further, random surface samples were collected from water faucets and sinks present in each ward. For each site, two repeat swabs were collected.

2.2.2. Processing of Swab Specimens

Of the two swabs from each site, one was inoculated onto nonselective media i.e., Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) containing chloramphenicol (25 mg/L) and gentamicin (40 mg/L) at 37 °C for 48–72 h. All yeast colonies that grew on SDA were purified and identified. The other swab was immersed in selective yeast nitrogen enrichment broth (YNB) containing 10% NaCl and 2% mannitol as a carbon source and vortexed and incubated at 37 °C for 72–96 h [20]. 400 µL of the broth was inoculated on one set each of CHROMagarTM Candida Plus agar [21], a differential medium for C. auris and CHROMagarTM Candida medium for 48 h at 37 °C. After 48 h, all colonies that grew on both CHROMagar plates were sub-cultured on SDA plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C for purification and identification.

2.2.3. Yeast Identification and Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

All yeast isolates were identified by MALDI TOF-MS (Bruker Biotyper OC version 3.1, Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) with a score value of >2 against the Bruker’s database and in-house C. auris database [22]. Yeast isolates not identified by MALDI TOF-MS were identified by amplification and sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and the D1/D2 domain of the large subunit rDNA (28S) followed by GenBank basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) pairwise sequence alignment (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/Blast.cgi) [3].

Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was performed using the CLSI broth microdilution method (BMD), following M38-Ed3 [23]. The antifungals tested were fluconazole (FLU, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), itraconazole (ITC, Lee Pharma, Hyderabad, India), voriconazole (VRC, Pfizer, Groton, CT, USA), posaconazole (POS, Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), isavuconazole (ISA, Basilea Pharmaceutical, Basel, Switzerland), 5-flucytosine (5-FC, Sigma), caspofungin (CFG, Merck), micafungin (MFG, Astellas, Toyama, Japan), anidulafungin (AFG, Pfizer) and amphotericin B (AMB, Sigma). The drugs were tested for 10 (two-fold) dilutions and the drug concentration ranges were: FLU, 0.25–128 mg/L; ITC, VRC, and AMB, 0.03–16 mg/L; POS, ISA, AFG, MFG, CFG, 0.015–8 mg/L; 5-FC, 0.125–64 mg/L. Candida krusei strain ATCC 6258 and Candida parapsilosis strain ATCC 22019 were used as quality control strains. The modal MIC, geometric mean (GM) MIC with 95% CIs, MIC50, MIC90, median, and range were calculated using Prism version 6.00 (GraphPad Software). The MIC endpoints for all the drugs except amphotericin B were defined as the lowest drug concentration that caused a prominent decrease in growth (50%) in relation to the controls. For amphotericin B, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which there was 100% inhibition of growth compared with the drug-free control wells.

2.2.4. Genome Sequencing, SNP Calling, and Phylogenetic Analysis

For genomic sequencing, the genomic DNA from representative C. auris isolates were extracted using a column-based method with a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and quantified by QUBIT 3 Fluorometer using dS DNA HS Dye. WGS libraries were prepared using NEBNext ultra II DNA FS kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). In brief, 200 ng of genomic DNA was enzymatically fragmented by targeting 200–300 bp fragments sizes followed by purification using AMPure beads (Beckman Coulter life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA). For sequencing, the libraries were normalized to 10 nMol/L concentrations and pooled together at equal volumes. Further, the library pools were denatured using freshly prepared 0.2 N NaOH for cluster generation on cBOT and sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 4000 [24].

Variant identification and phylogenetic analysis: Candida auris strain B8441 assembly V2 was obtained from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/38761?genome_assembly_id=353836) and used as the reference clade I strain. Further, genome sequences of 18 previously published Indian C. auris strains (B11200, B11201, B11205-B11207, B11209, B11210, B11212-B11218, VPCI_510/P/14, VPCI_692/P/12, VPCI_550/P/14, VPCI_479/P/13) [25,26] were retrieved for comparison. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified using the NASP pipeline (Northern Arizona SNP Pipeline, http://tgennorth.github.io/NASP/). Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.39 [27] and aligned against the reference genome using BWA v0.7.17 [28]. SNP sites were identified using GATK v2.7.4 [29]. The SNP sites were filtered if they were located in the repetitive regions of the reference genome, had a coverage lower than 10 x, or with less than 90% variant allele calls. For the phylogenetic analysis, 1154 SNP sites were concatenated. The maximum likelihood tree was constructed using RAxML based on 1000 bootstrap replicates and the ASC_GTRCAT nucleotide substitution model. The phylogeny was visualized using an online tool iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/).

To estimate the divergence time of the most recent common ancestor for the C. auris isolates, the Bayesian phylogenies were constructed with BEAST v2.6.3 [30] under a general time reversible nucleotide substitution model, and a strict clock model with clock rate set as 1.0 × 10−5. Further, a coalescent exponential population model was applied. The tip dates were assigned according to the sampling dates and year midpoint was applied to samples without the month and date information. The Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) took 50,000,000 steps in the chain, and tree samples were logged every 1000 steps. Tracer v1.7.1 [31] was used to visualize and analyze the posterior MCMC samples. The effective sample size for each parameter was over 700, indicating that the MCMC runs had converged. The maximum clade credibility tree was created using TreeAnnotator v2.6.3 after discarding the first 10% as burn-in, and visualized using FigTree v1.4.4.

2.2.5. Microsatellite Typing of C. auris

A single colony of C. auris was inoculated in 50 µL physiological saline (154 mM NaCl) and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C after addition of 200 U lyticase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequently, 450 µL physiological saline (154 mM NaCl) was added and the sample was incubated for 15 min at 100 °C and cooled down to room temperature. PCR amplification of the STR regions was performed on a thermocycler (Westburg-Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) using 1× Fast Start Taq polymerase buffer without MgCl2, dNTPs (0.2 mM), MgCl2 (3 mM), multiplex primers (0.2–0.8 µM), 1 U Faststart Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Germany), and DNA. A thermal protocol of 10 min denaturation at 95 °C, followed by 30 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 30 s denaturation at 95 °C, 30 s of annealing at 60 °C, and 1 min of extension at 72 °C, and a final incubation for 10 min at 72 °C. Subsequently, the PCR products were diluted 1:1000 in water, and 10 µL of diluent together with 0.12 µL orange 600 DNA size standard (NimaGen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) was incubated for 1 min at 95 °C. The copy numbers of the 12 markers were determined for all isolates using GeneMapper software 5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The size of the alleles was rounded. Relatedness between isolates was analysed using BioNumerics software version 7.6.1 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) via the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) using the multistate categorical similarity coefficient. All markers were given an equal weight.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Details and C. auris Colonisation

During the six-month-period (December 2019–May 2020), a total of 195 patients were admitted. Of these, 32 patients who had a history of chronic respiratory diseases (>6 months duration) and required prolonged and/or repeated hospitalisation were screened. Of the 32 patients screened, 37.5% patients (n = 12, mean age 51 years; male = 11, female = 1) had or developed C. auris colonisation while hospitalised. These 12 C. auris colonised patients were admitted in seven rooms of the medical ward.

The clinical details and C. auris positivity at weekly intervals are detailed in Table 1. The majority of the colonised patients had chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) along with post tuberculosis complications (n = 10). One patient each had HIV with pneumothorax and interstitial lung diseases (ILD) respectively (Table 1). Further, among the C. auris colonised cohort, 25% (n = 3) had underlying diabetes mellitus. Of the 12 patients colonised by C. auris, nine (75%) had a single site positive and three (25%) each had three sites positive. Further, the groin was the most frequently colonised site (75% n = 9) followed by nose (42%, n = 5) and ear (33%, n = 4). C. auris colonisation was detected in 25% (n = 3) of patients at the time of admission whereas the remaining patients (n = 9) developed colonisation after one week of admission. Overall, C. auris colonised patients (n = 12) were hospitalised for 10–150 days. Further, 75% (n = 9) of patients remained colonised till the day of discharge which ranged from 10 to 26 days whereas two patients had clearance of C. auris between 30 to 60 days. Further, three patients with C. auris colonisation were co-colonised with C. albicans (n = 2) and C. tropicalis (n = 1). In the remaining non-auris cohort of 20 patients, 14 were colonised by other yeasts and surveillance cultures in six patients remained negative for yeasts. C. parapsilosis and C. albicans represented the majority of non-auris cohort, including four patients each, followed by C. orthopsilosis and C. guilliermondii for a single patient each. Further, in three patients, C. parapsilosis showed co-colonisation with C. orthopsilosis in one; C. tropicalis, C. albicans, and C. guilliermondii in another (n = 1), and Lodderomyces elongisporus and C. orthopsilosis for the third patient (n = 1). One patient was co-colonised by C. tropicalis and C. glabrata. None of the colonised patients developed blood stream infections during hospitalisation.

Table 1.

Details of 12 Candida auris colonised patients.

| Patients Code | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Weekly Culture Positivity (Body Sites Colonised) | Duration of Hospitalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 * | On Discharge | ||||

| A | 52/M | COPD, DM, HTN, | - | - | + (G) |

+ (G) |

|

+ (G) |

26 days |

| B # | 60/M | COPD, Post tubercular cavity, DM, CPA | - | - | - | - | + (E,N,G) |

- | 150 days |

| C # | 64/M | COPD | - | - | + (G) |

+ (G) |

|

+ (G) |

25days |

| D # | 47/M | COPD, post tuberculosis complications | - | - |

+ (E,N,G) |

+ (E,N,G) |

- | - | 58 days |

| E | 52/M | HIV with pneumothorax | - | + (G) |

- | - | - | + (G) |

13 days |

| F | 48/M | COPD, bronchiectasis | - | + (E) |

+ (E) |

12 days | |||

| G | 42/M | Post tuberculosis complications, cor pulmonale | - | - | + (N) |

+ (N) |

- |

- | 33 days |

| H | 45/M | COPD, | + (N) |

+ (N) |

+ (N) |

13 days | |||

| I | 58/M | COPD, CPA | - | - | + (E,N,G) |

+ (E,N,G) |

- | + (E,N,G) |

23 days |

| J | 57/M | Post tuberculosis fibroatelectasis | - | - | + (G) |

+ (G) |

|

+ (G) |

24 days |

| K | 51/F | ILD, DM | + (G) |

+ (G) |

+ (G) |

+ (G) |

17 days | ||

| L | 61/M | COPD, post tubercular cavity | + (G) |

+ (G) |

|

+ (G) |

10 days | ||

- negative for C. auris. + positive for C. auris. * patients were screened every week till discharge (data after 5th week not included). # Patients isolates selected for whole genome sequencing. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; CPA, cardiopulmonary arrest; ILD, interstitial lung diseases; E, ear; N, nose; G, groin.

3.2. Yeast Identification and Evaluation of CHROMagarTM Candida Plus for C. auris

A total of 35 C. auris strains including 20 from 12 patients and 15 from environment samples were identified as C. auris by MALDI TOF-MS. Candida auris colonies were readily identified on selective CHROMagarTM Candida Plus medium after 48 h of incubation showing distinct cream colour colonies with blue halo. In contrast, on CHROMagar Candida medium, C. auris was difficult to differentiate from other species that showed pink colonies which included C. parapsilosis (pink), C. krusei (pink fuzzy growth), C. lusitaniae (pink), C. guilliermondii (pink) and Hyphopichia burtonii (pink). Interestingly none of the above-mentioned non-auris Candida spp. showed colony morphology specific for C. auris, i.e., pale cream with distinctive blue halo on CHROMagarTM Candida Plus medium [21].

3.3. Environmental C. auris

A total of 148 samples were collected from the environment of C. auris colonised patients during the study period. The results of environment sampling are detailed in Table 2. Overall, 10% (n = 15) of samples yielded C. auris. The maximum number of C. auris was recovered from floor (26.6%, n = 4) and bed railing (20%, n = 3), followed by patient bedside trollies (13.3%, n = 2). Further, C. auris was isolated from air conditioner air wings, bed sheet, pillow, mobile phone, and two medical equipment: oxygen mask and intravenous pole (IV) (Table 2). Out of 12 C. auris colonised patients, the environments of four patients (33.3%) were found to contain C. auris which included patients’ bed railing in three cases, followed by bed trolly (n = 2), and one case each of IV-pole, mobile phone of the patient, pillow, floor, and bed sheet. The environmental samples containing C. auris colonised patients became positive on an average of 8.5 days (duration 7–14 days) after patient’s colonisation was detected. Interestingly, environmental samples associated with the 20 non-auris yeast-colonised patients were all negative for C. auris. In addition, 13 yeast species other than C. auris were isolated from the environment screening specimens, including C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilosis, C. guilliermondii, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae, C. albicans, C. catenulata, Pichia kudriavzevii, Trichosporon asahii, Hypopichia burtonii, Kodamea ohmeri, and L. elongisporus (Table 2). Notably, pillow samples harboured the highest number of different yeast species (69%, 9 spp.), followed by floor (53.8%, 7 spp.), trollies (38.4%, 5 spp.), bed railing (30.7%, 4 spp.), sink (30.7%, 4 spp.), mobile (23%, 3 spp.), IV pole (23%, 3 spp.), bed sheet and air conditioner wings (15.3%, 2 spp.). Among these 13 species, five (C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. guilliermondii, L. elongisporus, and C. tropicalis) were found to colonise both patients and their environment.

Table 2.

Distribution of yeast species isolated from patients’ environment samples.

| Species (Number of Colonies) | Environment Sampling Sites (Number of Colonies) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floor | Railing | Bed Sheet | Bed Side Trolley | IV Pole | Nebuliser | Oxygen Mask | A.C Wings | Pillow | Sink Samples | Mobile | Wheel Chair | |

| C. auris (n = 15) | + (n = 4) | + (n = 3) | + (n = 1) | + (n = 2) | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 1) | - |

| C. parapsilosis sensu stricto (n = 75) | + (n = 22) | + (n = 13) | + (n = 4) | + (n = 5) | + (n = 9) | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 3) | + (n = 13) | + (n = 4) | + (n = 1) | - |

| C. orthopsilosis (n = 4) | - | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 1) | - |

| C. metapsilosis (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - |

| C. guilliermondii (n = 21) | + (n = 5) | - | + (n = 6) | + (n = 2) | + (n = 3) | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | - | + (n = 3) |

| C. tropicalis (n = 11) | + (n = 3) | + (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | + (n = 2) | + (n = 2) | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | - |

| C. lusitaniae (n = 5) | + (n = 3) | - | - | + (n = 2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| L. elongisporus (n = 3) | + (n = 3) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| T. asahii (n = 3) | + (n = 2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - |

| C. albicans (n = 3) | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | - | - |

| H. burtonii (n = 2) | - | - | - | - | + (n = 2) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| K. ohmeri (n = 2) | + (n = 1) | + (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| P. kudriavzevii (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - |

| C. catenulata (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + (n = 1) | - | - | - |

+ Positive for respective yeast species. - Negative for respective yeast species.

3.4. Genome Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis of C. auris Isolates

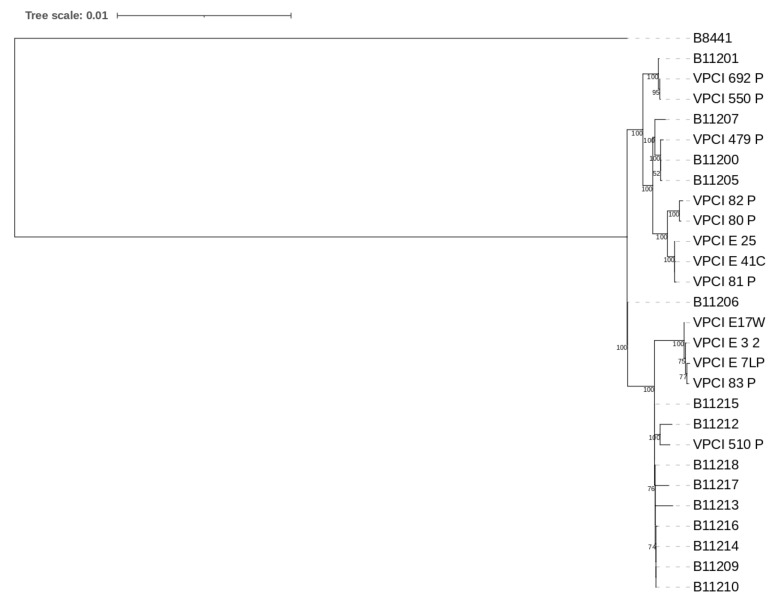

A total of nine C. auris isolates representing clinical (n = 4), and environmental (n = 5) samples were analysed by whole genome sequencing. The four clinical isolates were from 3 patients (B, C, and D) and they were collected in the first four months of sampling. To explore the link of transmission from patient to environment and vice versa, five strains were chosen that represented environmental isolates related with the above three patients. Due to cost constraints, we were unable to sequence all C. auris isolates. All our nine isolates clustered in Clade I (South Asian clade) and showed an average SNP difference of 92 (minimum = 1, max = 160) among each other (Figure 1). Isolates varied from the Clade I reference strain B8441 (Pakistan, clade 1) by a minimum SNP difference of 900 and a maximum range up to 921. The nucleotide diversity (pi) [32] in the sample of all 28 South Asian Clade I isolates, including the 18 Clade I isolates from India that were retrieved from GenBank [25,26], was 1.36 × 10−5.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree constructed based on 1000 bootstrap constructed by RAxML. Relationships among our nine strains and South Asian strains including 18 previously published Indian C. auris strains (B11200, B11201, B11205-B11207, B11209, B11210, B11212-B11218, VPCI_510/P/14, VPCI_692/P/12, VPCI_550/P/14, VPCI_479/P/13), and one reference Clade I strain B8441 from Pakistan.

Phylogenetic analysis of these nine sequenced isolates (Figure 1) showed two closely related clusters (1 and 2) with 100% boot strap value. Cluster 1 comprised of one isolate of patient D (VPCI/83/P/2020) and three environmental isolates collected from vicinity of patient D in a single ward (VPCI/E/7LP/2020 from floor, VPCI/E/17W/2020 from patient′s mobile, VPCI/E/3/2020 from pillow). These isolates showed limited genetic difference among them with SNP difference of ≤8. Cluster 2 included five C. auris isolates which could be further divided into two subgroups. One subgroup includes two samples, VPCI/80/P/2020 (Ear; Patient B) and VPCI/82/P/2020 (Ear; Patient D), and they showed seven SNPs differences between each other. The other subgroup comprises three isolates, VPCI/E/41C/2020 (Bed railing of patient I), VPCI/E/25/2020 (Bed railing; Patient B), and VPCI/81/P/2020 (groin; Patient C) and showed ≤3 SNP differences between each other. A range of 43–136 SNPs differences were observed between C. auris isolates of the present study and previously published C. auris isolates from four different hospitals in India [25].

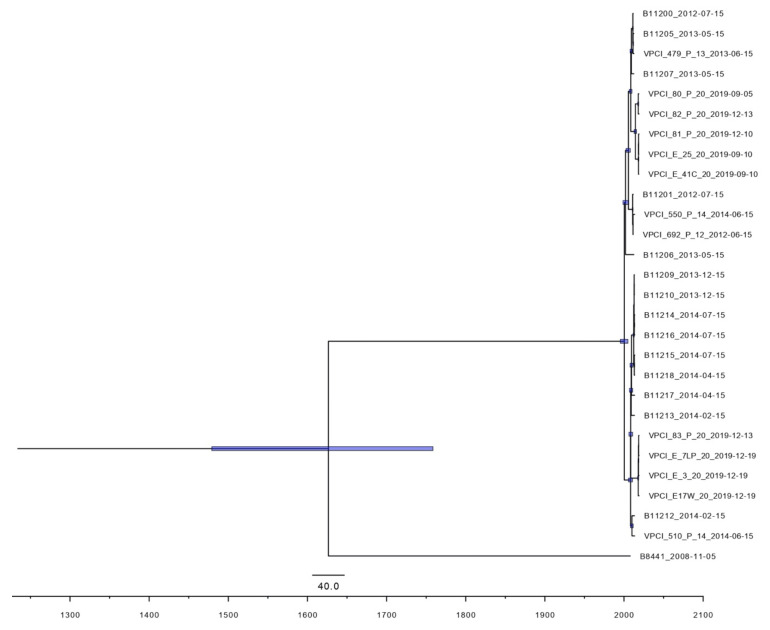

To investigate the transmission patterns of C. auris strains colonizing patients and their respective environment, we derived the divergence times of the isolated strains and other Indian C. auris isolates from the same clade I based on the base substitution and divergence time framework reported previously [33]. According to the phylogeny, the most recent common ancestor for the clade I Indian strains dates back to the year 1626 (95% highest posterior density, 260.3–539.8 years ago). Consistent with the results of phylogenetic analysis, nine isolates of this study also grouped into two clusters according to their time of emergence (Figure 2). Cluster 1 had four isolates, one from ear of patient D (VPCI/83/P/2020), and three environmental isolates (VPCI/E/7LP/2020, VPCI/E/17W/2020 and VPCI/E/3/2020) from the vicinity of the same patient. The most recent common ancestor among these four isolates was estimated to have emerged in 2018 (95% HPD, 0.5–1.7 years ago). Cluster 2 included isolates from patients B, C, D along with environment isolates, VPCI/E/25/2020 (bed railing, patient B) and VPCI/E/41C/2020 (bed railing, patient I), and this cluster was estimated to have emerged about five years ago (95% HPD, 4.2–7.4 years ago). All the nine isolates were submitted to GenBank under accession number SAMN17149510-18.

Figure 2.

Maximum clade credibility phylogenetic tree of 9 Candida auris strains (clinical, n = 4; environmental, n = 5) isolated in the present study, and 18 previously published Indian C. auris strains, (B11200, B11201, B11205-B11207, B11209, B11210, B11212-B11218, VPCI_510/P/14, VPCI_692/P/12, VPCI_550/P/14, VPCI_479/P/13) along with Clade1 isolate (B8441) using BEAST strict clock model and coalescent model. Values indicate the posterior probability of the nodes in the maximum clade credibility tree. Purple bars indicate 95% highest posterior density.

3.5. Microsatellite Analysis

A total of 26 C. auris isolates comprising 16 from nine colonised patients (A–I) and 10 from their environmental samples were included for STR typing (Table 3). Overall, three distinct STR types (1, 2, and 3) were detected among 26 C. auris strains collected from nine patients and their environment. These three STR types were relatively equally represented, 10 isolates had STR 2 and eight each had STR 1 and STR 3. These three STR patterns differed in one or two loci (M3-1 FAM, M3-2 FAM). STR 1 strains were detected in two patients (A and D) and also from the environment of patient D, admitted in the same room. Interestingly, in patient D, different body sites i.e., ear, nose and groin were colonised by C. auris strains with three distinct STRs. Specifically, two different STRs i.e., 1 and 2, colonised the ear of patient D. Further, groin and nose were colonised by STR 1 and 3 respectively. Notably, the environment of patient D harboured STRs 1 and 2 on the personal mobile phone, pillow and floor samples. Notably, Patient I who was admitted after patient D, was assigned the same bed as previously occupied by patient D and, similar to patient D, developed colonisation with STR 3 in the nose. The remaining six patients (B, C, E–H) were admitted in four different rooms. All clinical and environmental isolates from these six patients harboured two STRs i.e., 2 and 3. Interestingly, the close environment of patient B had STR 3 on the bed railing. However, the patient was colonised with STR 2.

Table 3.

Short tandem repeat genotypes of 26 Candida auris isolates (patient body surface n = 16, patient environment n = 10) by using microsatellite typing using 12 STR markers.

| Patient | Room No. | DOA/DOD | Patient Body Sites Positive for C. auris (STR Code) | Environment Sample Details (STR Code) | STR Code | M-2 | M3-I | M3-II | M9 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | a | b | c | ||||||

| A | 3 | 07-11-19/31-12-19 | Groin (1) | Negative | 1 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| B | 3 | 01-08-19/30-12-19 | Ear (2) * | Bed Railing (3) * | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| Nose (2) | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | ||||

| Groin (2) | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | ||||

| 3(BR) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| C | 1 | 21-11-19/17-12-19 | Groin (3) * | Negative | 3 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| D | 4 | 01-12-19/28-01-20 | Ear (1) * | Mobile (1) * | 1 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| Groin (1) | Pillow (1) * | 1 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Ear (2) * | Floor 1 (1) * | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Nose (3) | Floor 2 (1) | 3 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Floor 3 (1) | 1(M) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | ||||

| Floor 4 (2) | 1(P) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | ||||

| 1(F 1) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| 1(F 2) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| 1(F 3) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 60 | 10 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| 2(F 4) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| E | 2 | 15-01-20/28-01-20 | Groin (2) | Negative | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| F | 2 | 21-01-20/28-01-20 | Ear (2) | Negative | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| G | 2 | 03-01-20/06-02-20 | Nose (2) | Negative | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| H | 4 | 24-01-20/31-01-20 | Nose (3) | Negative | 3 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| I | 4 | 07-01-20/30-01-20 | Ear (2) | Oxygen mask (3) | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 |

| Groin (2) | Trolly (3) | 2 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 64 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Nose (3) | Bed railing (3) * | 3 | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||

| 3(OM) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| 3(T) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

| 3(BR) | 66 | 19 | 9 | 62 | 10 | 18 | 36 | 29 | 22 | 19 | 11 | 9 | |||||

Yellow, green and blue colours denote different STR genotypes, 1,2,3 respectively. DOA (Date of admission of patient), DOD (Date of discharge). * C. auris isolates selected for Whole genome sequencing. Env-Environment, BR-bed railing, M-mobile, P-pillow, F1-4-denotes different locations of the floor screened, OM-oxygen mask, T-trolly.

3.6. Comparison of Data Obtained with the STR Assay and WGS Analysis

C. auris strains that had identical STR varied by small SNP difference ranging 3–8 on WGS suggesting identical strains by both methods. Cluster 1 and two subgroups of cluster 2 identified by WGS represented three different STR types in each cluster/subgroup, suggesting concordant results by the microsatellite typing. WGS data of the three distinct genotypes detected in three patients (B, C, D) by STR analysis showed 30–150 SNP differences among each other. The isolates varied by one STR marker showed a SNP difference of 30 nucleotides whereas isolates varied by two STR markers showed a SNP difference of 150 nucleotides.

3.7. In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) and Mutation Analysis

3.7.1. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing

All of the 35 C. auris strains isolated from patients and their environment were subjected to in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing. MIC data against 10 antifungals tested are summarised in Table 4. All C. auris isolates in the present study were resistant to FLU (MICs ≥ 128 mg/L) barring one environmental isolate (MIC 16 mg/L) from the floor. Further, 25% clinical and 33% environmental C. auris isolates were non-susceptible to VRC (MIC ≥ 2 mg/L). Also 37% (n = 13) of isolates, including 23% (n = 8) clinical and 14% (n = 5) environmental, were resistant to AMB. Notably, 40% (n = 8/20) of clinical and 26.6% (n = 4/15) of environmental isolates were resistant to two classes of drugs (azoles+ AMB). Interestingly, C. auris isolates (VPCI/83/P/2020, VPCI/87/P/2020, VPCI/88/P/2020) from patient D and five isolates from the adjacent environment showed high MIC values of ≥2 mg/L against AMB. MFG and AFG showed MIC ranges below the proposed CDC tentative breakpoints (MIC ≥ 4 mg/L) for all isolates (Table 4).

Table 4.

MIC distribution of 35 C. auris, (patient body surface n = 20, patient environment n = 15) strains against 10 antifungal drugs tested using CLSI-BMD method.

| Drugs a | No. of Isolates with MIC/MEC (mg/L) | Range | GM b | MIC50 c | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | ≥128 | ||||

| FLU | 1 | 2 | 17 | 32–128 | 111.4 | 128 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 1 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 0.25–4 | 2.37 | 4 | ||||||||||

| VRC | 3 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 0.25–4 | 0.93 | 1 | |||||||||

| ISA | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 0.06–1 | 0.24 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| POS | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 0.015–0.5 | 0.19 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| AMB | 12 | 8 | 0.5–2 | 0.87 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||

| 5-FC | 4 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 0.06–0.5 | 0.20 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| MFG | 3 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 0.06–1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |||||||||

| AFG | 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 0.125–2 | 0.48 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| CFG | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 0.25–8 | 2.30 | 4 | |||||||||

| FLU | 1 | 3 | 11 | 16–128 | 97 | 128 | |||||||||||

| ITC | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1–4 | 2.30 | 2 | |||||||||||

| VRC | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0.25–4 | 1.09 | 1 | |||||||||

| ISA | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0.03–1 | 0.17 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| POS | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 0.03–0.25 | 0.13 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

| AMB | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.25–4 | 0.74 | 0.5 | |||||||||

| 5-FC | 4 | 10 | 1 | 0.03–0.125 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| MFG | 4 | 6 | 5 | 0.03–0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |||||||||||

| AFG | 6 | 3 | 6 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | |||||||||||

| CFG | 10 | 5 | 0.125–0.5 | 0.29 | 0.25 | ||||||||||||

Shaded region indicates range of drug dilution of the corresponding drug. a FLC, fluconazole; ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; ISA, isavuconazole; POS, posaconazole; AMB, amphotericin B; 5FC, flucytosine; AFG, anidulafungin; CFG, caspofungin; MFG, micafungin. b Geometric mean MICs, c MIC50, MIC at which 50% of test isolates were inhibited.

3.7.2. Genomic Analysis of Drug Resistant Genes

WGS analysis of nine isolates revealed the presence of two previously known amino acid substitutions associated with drug resistance, i.e., K143R (n = 5) or Y132F (n = 4) in the azole target ERG11 gene in all C. auris isolates analysed, including an environmental isolate showing a low MIC of FLU (MIC 16 mg/L, Y132F) [34,35]. Further, analysis of the TAC1B gene, a zinc-cluster transcription factor-encoding gene, showed a previously described amino acid substitution A640V [36] in five of nine isolates. Notably, amino acid substitution A640V in TAC1B was exclusively observed in C. auris isolates that had K143R amino acid substitution in the azole target ERG11 gene. Further, based on relative sequence read depth, five of nine (55.5%) C. auris isolates that harboured K143R amino acid substitution in the azole target ERG11 gene likely had two copies of the MDR1 gene (codes for a major facilitator transporter). Analysis of the ortholog of gene YMC1 identified one amino acid substitution G145D present in isolates without the K143R amino acid substitution. Ortholog of YMC1 has several transmembrane transporter activities and is essential in mitochondrial transport. Of note, all isolates have the (T > C) mutation in the 5′ end of this YMC1 ortholog.

Analysis of other genes homologous to those involved in ergosterol biosynthesis in the Baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ERG2, ERG3, ERG5, ERG6, ERG20, ERG24, ERG25, ERG26, ERG27, ERG28, and ERG29) revealed no amino acid substitutions relative to the reference strain B8441 in any of the nine strains, regardless of their susceptibility to AMB. Consistent with previous results showing all sequenced Clade I isolates having the MTLa locus, the mating type locus MTLa was found in all nine examined C. auris isolates. Also, all nine C. auris isolates analysed by WGS showed amino acid substitution K719N in the STE6 gene, an ABC family transporter which is only expressed in MTLa carrying strains and exports the a-factor pheromone in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans, as required for mating [37].

4. Discussion

In this study, we report C. auris colonisation and transmission among patients with chronic respiratory diseases hospitalised in the medical wards of a chest hospital. C. auris colonisation occurred in one third (37.5%, 12 of 32 patients) of hospitalised patients. Notably, 9.3% of the screened patients (n = 3/32) were colonised at the time of admission suggesting prolonged carriage from outside of the hospital as a potential source of hospital contamination. In the present study, high rates of colonisation in chronic respiratory patients were recorded. It is known that the rates of culture positive surveillance cases of C. auris varies in different healthcare facilities depending on the facility type. Previously, a contact tracing and epidemiologic investigation surrounding cases earlier in the C. auris epidemic in New York revealed that colonisation rates varied by facility type, i.e., hospitals (5%), long term care facilities (LTCF, 6.3%), long term acute care (2.9%), and co-located hospital and LTCF (12.3%) [38]. C. auris colonisation rates in skilled nursing facilities that cared for ventilated patients were nearly ten times higher than the prevalence in skilled nursing facilities that did not provide care for ventilated residents [38,39]. It is pertinent to emphasize that colonisation by C. auris predisposes patients at risk for invasive infection as 5–10% of known colonised patients have been reported to develop invasive infections [10]. However, in the present study, none of the colonised patients developed invasive infections, probably attributed to the fact that none were on ventilatory support nor had invasive devices implanted. Both mechanical ventilation and invasive devices are considered major risk factors for the development of invasive infections due to C. auris [40,41]. Nevertheless, hospital environment contamination by the colonised patients could serve as a potential source for exogenous acquisition of multidrug-resistant C. auris [42]. Overall, 10% of environmental samples in the present study yielded C. auris including patients’ several contact objects, such as bed railings, bed sheets, pillows, bed side trolley and personal mobile phone. All of these could serve as the source of colonisation among the hospitalised population. A previous report from six US acute care hospitals in four states showed that C. auris was uncommon in hospital environments (3.8% of high-touch surfaces, 3.4% of sink drains, and 0% of portable equipment) in centers experiencing C. auris outbreaks during a six-month period [43].

To determine if environmental isolates of C. auris were genetically related to isolates that colonise patients, we undertook WGS and microsatellite genotyping. Interestingly, both techniques documented that multiple strains/genotypes contaminated the hospital environment and colonised patients. Further, we identified that genetically diverse strains colonised different body sites of patients. WGS identified close genetic relationships of strains (8–30 SNP variation) that colonised patients and their close environment probably due to shedding of the viable yeasts in the environment. Further, TMRCA analysis of an isolate from a single patient who developed colonisation after one week of admission suggested that the strain emerged prior to the study period and the patient probably acquired it from the environment. Interestingly, C. auris was not detected in the environment or rooms of patients who were not colonised by C. auris suggesting that the immediate environment is a potential source in acquiring C. auris in the hospital setting. Microsatellite length polymorphism (MLP) typing using short tandem repeats (STRs) has recently been validated for C. auris [18]. In the present study identical STR types differed by only 3–8 SNPs with WGS whereas different STR types exhibited 30–150 SNPs, suggesting concordant correlation among genomic analysis and STR genotyping. C. auris has a wide genetic diversity as evident by the previous genomic data analysis of 304 C. auris isolates from 19 countries. In addition, a wide genomic variability (SNP range, 43–136) among the C. auris population, circulating in different hospitals in India, was observed by WGS [33]. The present report extends the validation of STR typing in transmission settings and underscores the need of further analysis of this technique considering the wider genetic diversity of C. auris [44].

Identification of novel genetic determinants of antifungal susceptibilities significantly adds to the understanding of clinical antifungal resistance in C. auris. The genomic investigation of drug resistant genes implicated in fluconazole resistance in the present study showed the presence of either K143R or Y132F mutations in ERG11 gene in clinical and environmental isolates of C. auris. Interestingly, a single C. auris isolate that had a low MIC of 16 mg/L for fluconazole also harboured Y132F amino acid substitution. This result suggests that other mechanisms also contribute to the development of fluconazole resistance. Also, 55% of C. auris isolates likely had two copies of the MDR1 gene. A recent study analysed a global collection of C. auris isolates and demonstrated that a multitude of resistance-associated TAC1B mutations are present among the majority of fluconazole-resistant C. auris isolates specific to a subset of lineages or clades [36]. We observed that azole resistant C. auris isolates harboured amino acid substitution A640V (coexisting with K143R) in the zinc-cluster transcription factor-encoding gene TAC1B, suggesting that this mutation may provide additive fluconazole resistance in Indian C. auris isolates.

The molecular mechanisms of amphotericin B resistance and multiple drug resistance are poorly understood in C. auris. The present study reports high (37%) amphotericin B resistance in C. auris isolates colonizing patients and their environment. The acquisition of resistance to polyenes has been linked to mutations in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in Candida spp, including ERG2 [45], ERG6 [46], ERG11 [47], and ERG3 [48,49,50]. Recently, Ahmad et al., showed that a non-synonymous mutation in ERG2 can lead to reduced susceptibility of amphotericin B in clinical Candida glabrata isolates [51]. However, no amino acid substitution was found in ERG2 in any of our nine sequenced strains. The results suggest that resistance to amphotericin B is likely mediated by other genomic mutations. A recent report by Shivarathri et al. [52] described the role of the two-component signal transduction system and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway in drug resistance against AMB. The study demonstrated that genetic removal of SSK1, encoding a response regulator and the mitogen-associated protein kinase HOG1, restores the susceptibility to amphotericin B (AMB) in Indian C. auris clinical strains [52]. To tackle this yeast fundamental knowledge of mechanisms associated with amphotericin resistance and MDR in C. auris is warranted. Finally, to contain the spread of C. auris in healthcare settings, it is important to identify reservoirs and implement effective infection control practices [41]. During the early four-month-period of the study, routine cleaning and disinfection of patient rooms included use of a quaternary ammonium disinfectant once daily for disinfection of high-touch surfaces and a bleach wipe for post-discharge cleaning and disinfection. However, after the onset of the COVID 19 pandemic in late March in Delhi, India, the admission of chronic patients was limited. Further, COVID 19 pandemic control measures were placed stringently and enhanced cleaning procedures were implemented including using 1% sodium hypochlorite to clean and disinfect common surfaces 2–3 times a day. Resampling of C. auris positive environment in all the rooms showed clearance of C. auris from the environment, suggesting a high efficiency of 1% sodium hypochlorite against C. auris and a potential mechanism to prevent the transmission of this nosocomial yeast in a healthcare setting.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the University Grants Commission Research Fellowship, India to A.Y. (16-9/2019(NET/CSIR).

Author Contributions

A.C. designed the study; A.Y and A.S (Anubhav Singh) contributed to sample collection from patient and environment; M.H.v.H. and T.d.G. performed STR typing; Y.W. performed WGS analysis; A.C., A.S. (Ashutosh Singh), and A.Y. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript; A.C., J.F.M., T.d.G., and J.X. edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the VPCI (2019/2401).

Informed Consent Statement

Routine screening of patients is done under the surveillance protocol of the Institute.

Data Availability Statement

All the nine isolates were submitted to GenBank under accession number SAMN17149510-18.

Conflicts of Interest

All other authors declare no potential conflict of interest. We alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parra-Giraldo C.M., Valderrama S.L., Cortes-Fraile G., Garzón J.R., Ariza B.E., Morio F., Linares-Linares M.Y., Ceballos-Garzón A., de la Hoz A., Hernandez C., et al. First report of sporadic cases of Candida auris in Colombia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018;69:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhary A., Sharma C., Duggal S., Agarwal K., Prakash A., Singh P.K., Jain S., Kathuria S., Randhawa H.S., Hagen F., et al. New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India: New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1670–1673. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowdhary A., Anil Kumar V., Sharma C., Prakash A., Agarwal K., Babu R., Dinesh K.R., Karim S., Singh S.K., Hagen F., et al. Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;33:919–926. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-2027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam R.D., Revathi G., Okinda N., Fontaine M., Shah J., Kagotho E., Castanheira M., Pfaller M.A., Maina D. Analysis of Candida auris fungemia at a single facility in Kenya. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;85:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alfouzan W., Ahmad S., Dhar R., Asadzadeh M., Almerdasi N., Abdo N.M., Joseph L., de Groot T., Alali W.Q., Khan Z., et al. Molecular epidemiology of Candida auris outbreak in a major secondary-care hospital in Kuwait. J. Fungi. 2020;6:307. doi: 10.3390/jof6040307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Maani A., Paul H., Al-Rashdi A., Wahaibi A.A., Al-Jardani A., Al Abri A.M.A., AlBalushi M.A.H., Al-Abri S., Al Reesi M., Al Maqbali A., et al. Ongoing challenges with healthcare-associated Candida auris outbreaks in Oman. J. Fungi. 2019;5:101. doi: 10.3390/jof5040101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sana F., Hussain W., Zaman G., Satti L., Khurshid U., Khadim M.T. Candida auris outbreak report from Pakistan: A success story of infection control in ICUs of a tertiary care hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019;103:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Schalkwyk E., Mpembe R.S., Thomas J., Shuping L., Ismail H., Lowman W., Karstaedt A.S., Chibabhai V., Wadula J., Avenant T., et al. Epidemiologic shift in candidemia driven by Candida auris, South Africa, 2016–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:1698–1707. doi: 10.3201/eid2509.190040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Gaitán A., Moret A.M., Tasias-Pitarch M., Aleixandre-López A.I., Martínez-Morel H., Calabuig E., Salavert-Lletí M., Ramírez P., López-Hontangas J.L., Hagen F., et al. An outbreak due to Candida auris with prolonged colonisation and candidaemia in a tertiary care European hospital. Mycoses. 2018;61:498–505. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schelenz S., Hagen F., Rhodes J.L., Abdolrasouli A., Chowdhary A., Hall A., Ryan L., Shackleton J., Trimlett R., Meis J.F., et al. First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2016;5:35. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0132-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eyre D.W., Sheppard A.E., Madder H., Moir I., Moroney R., Quan T.P., Griffiths D., George S., Butcher L., Morgan M., et al. A Candida auris outbreak and its control in an intensive care setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:1322–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams E., Quinn M., Tsay S., Poirot E., Chaturvedi S., Southwick K., Greenko J., Fernandez R., Kallen A., Vallabhaneni S., et al. Candida auris in healthcare facilities, New York, USA, 2013–2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:1816–1824. doi: 10.3201/eid2410.180649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvo B., Melo A.S.A., Perozo-Mena A., Hernandez M., Francisco E.C., Hagen F., Meis J.F., Colombo A.L. First report of Candida auris in America: Clinical and microbiological aspects of 18 episodes of candidemia. J. Infect. 2016;73:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escandón P., Chow N.A., Caceres D.H., Gade L., Berkow E.L., Armstrong P., Rivera S., Misas E., Duarte C., Moulton-Meissner H., et al. Molecular epidemiology of Candida auris in Colombia reveals a highly related, countrywide colonization with regional patterns in amphotericin B resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019;68:15–21. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piedrahita C.T., Cadnum J.L., Jencson A.L., Shaikh A.A., Ghannoum M.A., Donskey C.J. Environmental surfaces in healthcare facilities are a potential source for transmission of Candida auris and other Candida species. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017;38:1107–1109. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes J., Abdolrasouli A., Farrer R.A., Cuomo C.A., Aanensen D.M., Armstrong-James D., Fisher M.C., Schelenz S. Genomic epidemiology of the UK outbreak of the emerging human fungal pathogen Candida auris. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0045-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow N.A., Gade L., Tsay S.V., Forsberg K., Greenko J.A., Southwick K.L., Barrett P.M., Kerins J.L., Lockhart S.R., Chiller T.M., et al. Multiple introductions and subsequent transmission of multidrug-resistant Candida auris in the USA: A molecular epidemiological survey. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:1377–1384. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Groot T., Puts Y., Berrio I., Chowdhary A., Meis J.F. Development of Candida auris short tandem repeat typing and its application to a global collection of isolates. mBio. 2020;11:e02971-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02971-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz-Gaitán A., Martínez H., Moret A.M., Calabuig E., Tasias M., Alastruey-Izquierdo A., Zaragoza Ó., Mollar J., Frasquet J., Salavert-Lletí M., et al. Detection and treatment of Candida auris in an outbreak situation: Risk factors for developing colonization and candidemia by this new species in critically ill patients. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2019;17:295–305. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2019.1592675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsh R.M., Bentz M.L., Shams A., Houston H., Lyons A., Rose L.J., Litvintseva A.P. Survival, persistence, and isolation of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogenic yeast Candida auris on a plastic health care surface. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55:2996–3005. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00921-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borman A.M., Fraser M., Johnson E.M. CHROMagarTM Candida Plus: A novel chromogenic agar that permits the rapid identification of Candida auris. Med. Mycol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/mmy/myaa049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kathuria S., Singh P.K., Sharma C., Prakash A., Masih A., Kumar A., Meis J.F., Chowdhary A. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris misidentified as Candida haemulonii: Characterization by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and DNA sequencing and its antifungal susceptibility profile variability by Vitek 2, CLSI broth microdilution, and Etest method. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:1823–1830. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00367-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi—Approved Standard CLSI Document M38-Ed3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA, USA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh A., Masih A., Monroy-Nieto J., Singh P.K., Bowers J., Travis J., Khurana A., Engelthaler D.M., Meis J.F., Chowdhary A. A unique multidrug-resistant clonal Trichophyton population distinct from Trichophyton mentagrophytes/Trichophyton interdigitale complex causing an ongoing alarming dermatophytosis outbreak in India: Genomic insights and resistance Profile. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019;133:103266. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.103266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma C., Kumar N., Pandey R., Meis J.F., Chowdhary A. Whole genome sequencing of emerging multidrug resistant Candida auris isolates in India demonstrates low genetic variation. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;13:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockhart S.R., Etienne K.A., Vallabhaneni S., Farooqi J., Chowdhary A., Govender N.P., Colombo A.L., Calvo B., Cuomo C.A., Desjardins C.A., et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;64:134–140. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv. 2013bio/1303.3997 [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A map reduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drummond A.J., Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rambaut A., Drummond A.J., Xie D., Baele G., Suchard M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018;67:901–904. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syy032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nei M., Li W.H. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:5269–5273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chow N.A., Muñoz J.F., Gade L., Berkow E.L., Li X., Welsh R.M., Forsberg K., Lockhart S.R., Adam R., Alanio A., et al. Tracing the evolutionary history and global expansion of Candida auris using population genomic analyses. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.03364-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chowdhary A., Prakash A., Sharma C., Kordalewska M., Kumar A., Sarma S., Tarai B., Singh A., Upadhyaya G., Upadhyay S., et al. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009–2017) in India: Role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:891–899. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Healey K.R., Kordalewska M., Jiménez Ortigosa C., Singh A., Berrío I., Chowdhary A., Perlin D.S. Limited ERG11 mutations identified in isolates of Candida auris directly contribute to reduced azole susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;62 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01427-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rybak J.M., Muñoz J.F., Barker K.S., Parker J.E., Esquivel B.D., Berkow E.L., Lockhart S.R., Gade L., Palmer G.E., White T.C., et al. Mutations in TAC1B: A novel genetic determinant of clinical fluconazole resistance in Candida auris. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00365-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsueh Y.-P., Shen W.-C. A homolog of Ste6, the a-factor transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for mating but not for monokaryotic fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:147–155. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.1.147-155.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossow J., Ostrowsky B., Adams E., Greenko J., McDonald R., Vallabhaneni S., Forsberg K., Perez S., Lucas T., Alroy K.A., et al. Factors associated with Candida auris colonization and transmission in skilled nursing facilities with ventilator units, New York, 2016–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacilli M., Kerins J.L., Clegg W.J., Walblay K.A., Adil H., Kemble S.K., Xydis S., McPherson T.D., Lin M.Y., Hayden M.K., et al. Regional emergence of Candida auris in Chicago and lessons learned from intensive follow-up at one ventilator-capable skilled nursing facility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caceres D.H., Forsberg K., Welsh R.M., Sexton D.J., Lockhart S.R., Jackson B.R., Chiller T. Candida auris: A review of recommendations for detection and control in healthcare settings. J. Fungi. 2019;5:111. doi: 10.3390/jof5040111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenters N., Kiernan M., Chowdhary A., Denning D.W., Pemán J., Saris K., Schelenz S., Tartari E., Widmer A., Meis J.F., et al. Control of Candida auris in healthcare institutions: Outcome of an international society for antimicrobial chemotherapy expert meeting. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2019;54:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chowdhary A., Voss A., Meis J.F. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris: “new kid on the block” in hospital-associated infections? J. Hosp. Infect. 2016;94:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar J., Eilertson B., Cadnum J.L., Whitlow C.S., Jencson A.L., Safdar N., Krein S.L., Tanner W.D., Mayer J., Samore M.H., et al. Environmental contamination with Candida species in multiple hospitals including a tertiary care hospital with a Candida auris outbreak. Pathog. Immun. 2019;4:260–270. doi: 10.20411/pai.v4i2.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuomo C.A., Alanio A. Tracking a global threat: A new genotyping method for Candida auris. mBio. 2020;11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00259-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vincent B.M., Lancaster A.K., Scherz-Shouval R., Whitesell L., Lindquist S. Fitness Trade-Offs Restrict the evolution of resistance to Amphotericin, B. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen-Pergakes K.L., Kennedy M.A., Lees N.D., Barbuch R., Koegel C., Bard M. Sequencing, disruption, and characterization of the Candida albicans sterol methyltransferase (ERG6) Gene: Drug susceptibility studies in Erg6 mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1160–1167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.5.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vale-Silva L.A., Coste A.T., Ischer F., Parker J.E., Kelly S.L., Pinto E., Sanglard D. Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Δ5,6-desaturase gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1960–1968. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05720-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanglard D., Ischer F., Parkinson T., Falconer D., Bille J. Candida albicans mutations in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway and resistance to several antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2404–2412. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2404-2412.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martel C.M., Parker J.E., Bader O., Weig M., Gross U., Warrilow A.G.S., Kelly D.E., Kelly S.L. A clinical isolate of Candida albicans with mutations in ERG11 (Encoding Sterol 14alpha-Demethylase) and ERG5 (Encoding C22 Desaturase) is cross resistant to azoles and Amphotericin, B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3578–3583. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00303-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morio F., Pagniez F., Lacroix C., Miegeville M., Le Pape P. Amino acid substitutions in the Candida albicans sterol Δ5,6-desaturase (Erg3p) confer azole resistance: Characterization of two novel mutants with impaired virulence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2131–2138. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad S., Joseph L., Parker J.E., Asadzadeh M., Kelly S.L., Meis J.F., Khan Z. ERG6 and ERG2 are major targets conferring reduced susceptibility to Amphotericin B in clinical Candida glabrata isolates in Kuwait. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018;63:e01900-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01900-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shivarathri R., Jenull S., Stoiber A., Chauhan M., Mazumdar R., Singh A., Nogueira F., Kuchler K., Chowdhary A., Chauhan N. The two-component response regulator Ssk1 and the mitogen-activated protein kinase Hog1 control antifungal drug resistance and cell wall architecture of Candida auris. mSphere. 2020;5 doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00973-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the nine isolates were submitted to GenBank under accession number SAMN17149510-18.