Abstract

Type I (classic) galactosemia, galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT)-deficiency is a hereditary disorder of galactose metabolism. The current therapeutic standard of care, a galactose-restricted diet, is effective in treating neonatal complications but is inadequate in preventing burdensome complications. The development of several animal models of classic galactosemia that (partly) mimic the biochemical and clinical phenotypes and the resolution of the crystal structure of GALT have provided important insights; however, precise pathophysiology remains to be elucidated. Novel therapeutic approaches currently being explored focus on several of the pathogenic factors that have been described, aiming to (i) restore GALT activity, (ii) influence the cascade of events and (iii) address the clinical picture. This review attempts to provide an overview on the latest advancements in therapy approaches.

Keywords: galactosemia type 1, classic galactosemia, galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT), gene therapy, mRNA therapy, pharmacological chaperones, transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), Babble Boot Camp (BBC)

1. Introduction

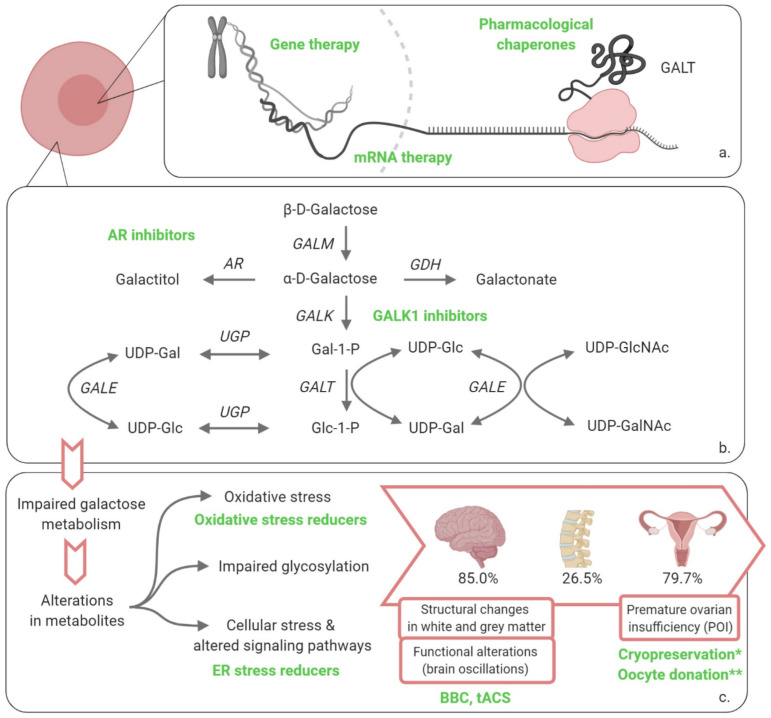

The galactosemias are a rare group of hereditary disorders of galactose metabolism. To date, four types have been described, each affecting a different step in the main route of galactose disposal: type I, galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase- (GALT, EC 2.7.7.12); type II, galactokinase- (GALK1, EC 2.7.1.6); type III UDP-galactose 4 epimerase- (GALE, EC 5.1.3.2) and the recently described type IV galactose mutarotase- (GALM, EC 5.1.3.3) deficiency, Figure 1 [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. We focus on type I galactosemia and review the latest advancements in therapy approaches.

Figure 1.

Overview of disorders of galactose metabolism and novel therapeutic approaches recently investigated or under investigation for classic galactosemia. (a) Transcription and translation leading to the production of enzyme, therapies restoring enzyme activity; (b) Leloir pathway of galactose metabolism and alternative routes of galactose disposal; (c) impaired galactose metabolism leading to long-term organ damage. * cryopreservation: more data have become available in the last 5 years; ** oocyte donation: recommendations for CG regarding this procedure have been formulated by a group of experts in the last 5 years. GALM, galactose mutarotase; GALK1, galactokinase 1; Gal-1-P, galactose-1-phosphate; GALT, galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase; Glc-1-P, glucose-1-phosphate; GALE, UDP-galactose 4′-epimerase; UDP-Gal, uridine diphosphate-galactose; UDP-Glc, uridine diphosphate-glucose; UGP, UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase; UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine; UDP-GalNAc, UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine; AR, aldose reductase; GDH, galactose dehydrogenase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; BBC, Babble Boot Camp; tACS, transcranial alternating current stimulation. Created with BioRender.com.

In type I, classic galactosemia (OMIM 230400), the conversion of -d-galactose-1-phosphate (Gal-1-P) to -d-glucose-1-phosphate (Glc-1-P) and uridine diphosphate-galactose (UDP-Gal) is hampered by the severe GALT deficiency. It is an autosomal recessive disorder with a prevalence of 1:16,000 to 1:50,000 live births in Western countries [9,10,11,12,13,14]. The current cornerstone of treatment, a galactose-restricted diet, resolves the neonatal syndrome but fails to prevent burdensome chronic impairments. Most affected patients develop brain impairments (85.0%), primary ovarian insufficiency (79.9%) and a diminished bone mineral density (26.5%) (data based on a large cohort from the Galactosemia network registry (Registry | GalNet (galactosemianetwork.org)). Additionally, data showed that a more favorable outcome among patients is achieved by onset of the diet in the first week of life and detection by newborn screening (NBS). Furthermore, a less strict diet (lactose free without further restrictions) was associated with less neurological complications [6,15]. There is a need for a more adequate treatment to prevent complications.

Classic galactosemia is caused by pathogenic genetic variants in the GALT gene, which is located on chromosome 9, leading to a severely diminished enzymatic activity [16]. At present, over 300 genetic variants in the GALT gene have been described, the most frequent disease-causing variant among people of European ancestry being the NM_000155.4: c.563A>G genetic variant (p.Gln188Arg) [17]. In addition to classic galactosemia, clinical variants with a higher residual activity are being detected through NBS in which a milder phenotype is anticipated. Structural and functional studies show that in the majority of genetic variants, the dysfunction of the enzyme is due to changes in protein stability and folding [4,5,7,18]. The most frequent genetic variants are NM_000155.4: c.563A>G (p.Gln188Arg); NM_000155.4: c.404C>T (p.Ser135Leu); and NM_000155.4: c.855G>T (p.Lys285Asn) [4,5,7,18].

The pathogenic mechanisms underlying the acute and long-term organ-specific complications of classic galactosemia are complex and remain to be fully elucidated. Currently described contributing factors include accumulation of galactose metabolites (galactitol, galactonate and Gal-1-P) [2,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], uridine diphosphate (UDP)-hexose alterations and impaired glycosylation [21,25,31,32,33,34,35,36], endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress with subsequent unfolded protein response (UPR), induction and alteration of signaling pathways [2,3,4,37,38,39,40,41,42], and oxidative stress [4,29,43,44] (Figure 1).

In recent years, a number of animal models (mouse, fruit fly, zebrafish, rat) [24,29,45,46] of classic galactosemia have been developed that mimic, at least partly, the biochemical and clinical phenotypes and complement the cellular models, allowing us to advance our comprehension of the complex playing field of the metabolism of galactose. We have learned that there is different expression of the Leloir pathway components and alternative galactose disposal routes in the different tissues, that combined with specific tissue demands, epigenetic and environmental factors, urge to revisit our understanding. GALT activity levels in affected organs (brain, ovaries) do not seem to differ from the activity levels in organs not affected in classic galactosemia and distinct organ-specific levels of GALT activity have been found [19]. This is reflected in the tissue related differences in relative levels of galactose metabolites (galactitol, galactose and Gal-1-P) in the rat galactosemia model [45], as well as in the nucleotide sugar profiles variation through development and in the different tissues in the zebrafish galactosemia model [31]. Besides, activity differs across different stages in development [19].

The recent elucidation of the crystal structure of human GALT, with a resolution of 1.9 Å, has provided a framework for understanding the molecular consequences of genetic variants and can greatly contribute to the design of therapeutic compounds [5,7]. Novel therapeutic approaches for classic galactosemia currently (defined as: in the last 5 years) being explored aim either to (i) restore GALT activity, (ii) influence the cascade of events or (iii) address the clinical picture. For these strategies to be optimal, characterization of the window of opportunity for treatment is of outmost importance; e.g., neonatal and early infancy or through adolescence or lifelong treatment.

2. Potential Therapies

2.1. Restoring GALT Activity

Directly restoring GALT activity is the aim of multiple techniques currently being investigated: (i) GALT gene therapy, (ii) mRNA therapy and (iii) pharmacological chaperones. Notably, restoring GALT activity up to 10–15% is likely to rescue the phenotype in classic galactosemia. This is suggested by in the so-called “biochemical variant galactosemia” where GALT activity levels between 10% and 15% do not result in clinical disease [47,48].

2.1.1. Gene Therapy

Gene therapy and gene correction techniques aim to permanently compensate for the primary genetic defect [49,50]. In conventional gene therapy, this is achieved by providing patients with the correct coding DNA (cDNA) sequence of the defective gene leading to the expression of normal protein [50,51]. Delivery is accomplished by the use of vectors, either viral or non-viral, containing the genetic sequence of the protein [49,52,53]. In recent decades, significant advances have been made and gene therapy is showing great promise in animal models and clinical trials of inborn errors of metabolism [51,52,53].

In classic galactosemia, viral mediated in vivo gene therapy is currently being investigated using recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors [54], which are emerging in the field of gene therapy as very promising [51,52,53]. Rasmussen et al. recently showed, in a pilot study in a galactosemia rat model (n = 7), that neonatal human GALT gene therapy with a AAV9 vector via tail vein injection led to GALT restoration in both liver and brain [54]. Relative to wildtype activity, GALT activity levels of 64–595% in liver and 2–42% in brain were found without significant adverse effects. Furthermore galactose metabolites in blood, liver and brain were lowered and a positive effect on cataract was observed [54]. Lai and Loiler expanded the serotypes of the AAV vectors to include AAV8 and AAVrh10, and showed that intravenous administration of AAV8-hGALT and AAVrh10-hGALT resulted in GALT (hGALT) protein expression and decreased levels of Gal-1-P in liver, brain, ovaries and red blood cells of Galt knockout mice [55]. In line with this data, Brophy et al. showed that a recombinant AAV vector encoding GALT was able to rescue GALT activity and reduce galactose-induced ER stress in fibroblasts from galactosemic patients [56].

Important future challenges will be focused at safety and efficacy. Safety concerns encompass elicited immune responses by the viral vector capsid proteins and the transgene product, and possible off target effects leading to insertional mutagenesis as well as genomic instability [49,52]. With regard to efficacy, Rasmussen et al. reported differences between liver and brain transgene activity. The authors hypothesized that these differences might stem from preferential perfusion of the liver and limited permeability of the blood–brain barrier and might reflect the differences in activity level of the organs [54]. These findings are consistent with prior reports on AAV9 transgene delivery by intravenous injection [57,58]. The reported studies illustrate the potential of gene therapy for the treatment of GALT-deficient galactosemia.

2.1.2. mRNA Therapy

Exogenous, intracellular delivery of mRNA is emerging as a new class of medicine [59,60,61,62]. Recent advances in mRNA technology have led to improvements in stability and translation by codon optimization and encapsulation within biodegradable delivery systems, preserving mRNA integrity and allowing targeted intracellular delivery [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. The required repeated dosing of this therapeutic modality tends to raise concerns about immunogenicity and therapy burden for the patients. As with gene therapy targeting, potential long-term adverse effects therapeutic index and dosing interval of mRNA remain important challenges for the future [60,68,70]. The transient nature of the mRNA requiring repeated dosing to remain effective also bears an advantage, by allowing individual dose titration and cessation of therapy if necessary [60,68,70].

Several preclinical studies evaluating the potential of systemically administered mRNA in metabolic disorders have shown that mRNA provides transient, half-life dependent protein expression, while bearing a low risk of insertional mutagenesis and maintaining dose-responsiveness [67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75]. This therapeutic approach is being explored in classic galactosemia using lipid nanoparticles as delivery system. Balakrishnan et al. recently showed in adult Galt knockout mice that systemic administration of LNP-packaged mouse and hGALT mRNA resulted in hepatic expression of active, long-lasting GALT enzyme and effectively eliminated galactose 1-phosphate in liver and other peripheral tissues [68]. Using the galt knockout zebrafish model, Haskovic et al. also showed successful delivery and translation of functional hGALT after single dose injections with LNP-packaged hGALT mRNA (n = 3) delivered at day 0 and measured on day 5 post fertilization (dpf) [76]. The mRNA approach holds great promise as a potential therapy for classic galactosemia.

2.1.3. Pharmacological Chaperones

Pharmacological chaperones are small molecules that bind specifically to their targets, rescuing specific variant proteins by facilitating intracellular folding and trafficking, increasing cellular stability and activity, and/or preventing premature degradation [4,21]. Pharmacological chaperones present advantageous features: (i) low synthesis cost; (ii) oral availability with broad biodistribution; (iii) low molecular weight that can potentially, allow them to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [77,78,79]. The high occurrence of missense mutations (>60%) [17] and experimental evidence of misfolding and decreased stability of GALT variants makes classic galactosemia highly amenable to this therapeutic approach [18,77,78,79,80,81].

Arginine supplementation, known for its effect as an aggregation inhibitor [82] has been studied as a potential therapeutic approach for classic galactosemia. Despite promising results of this chemical chaperone in a bacterial model [83], in a pilot study with 4 patients carrying the NM_000155.4: c.563A>G (p.Gln188Arg) mutation, arginine did not lead to improved GALT stability nor GALT activity levels as there was no improvement in galactose oxidation capacity [4,84].

Despite being a promising therapeutic approach, its specificity for genetic variants and compound heterozygosity in patient profiles as well as the existence of a broad range of genetic variants complicate the development of pharmacological chaperones as a therapy for all galactosemia patients.

2.2. Influence the Cascade of Events

These therapies focus on one of the downstream effects, and as such are less likely to provide treatment for the complete clinical picture of the disease. However, every approach can be helpful by tackling one of the aspects involved in pathophysiology and the combination of treatments could also be an option. The main approaches currently being explored to influence downstream phenomena are inhibitors of galactokinase 1 (GALK1)- and aldose reductase (AR), and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress reducers. Oxidative stress reducers have also been proposed in the past, but have not been studied in the last 5 years [43,44,85].

2.2.1. Galactokinase 1 (GALK1) Inhibitors

GALK1 inhibitors were proposed as treatment strategy many years ago [86], and have been thoroughly investigated over the years. The strategy aims to reduce the accumulation of Gal-1-P in GALT deficiency, as Gal-1-P is considered a major key player in the pathogenic mechanism in classic galactosemia [4,12,21]. The milder clinical picture of type II (GALK1 deficiency) galactosemia supported this view although standardized follow-up data are currently lacking [87,88]. Inhibition of GALK1 appears to be an attractive therapeutic target, since GALK1, as member of the GHMP kinase family, is highly substrate specific and no other undesired inhibitions are to be expected [89,90].

High-throughput screenings (HTS) have identified candidate ligands with affinity for GALK1 [12,91,92,93,94]. Promising compounds have been identified and studied to optimize the efficacy and improve the potency. Several compounds have also been tested in cell culture models of patients’ fibroblasts where their efficacy to reduce the biochemical phenotype by lowering Gal-1-P levels has been shown [89,90,91,92,94,95]. The effect of a possible increase in galactitol and galactonate levels remains to be investigated. More research with these compounds beyond cellular models is warranted.

2.2.2. Aldose Reductase (AR) Inhibitors

Aldose reductase (AR) inhibitors target the NADPH-dependent aldose reductase conversion of [2,21,61,96] galactose to galactitol, which cannot be transported across the cell membrane due to its poor diffusivity and cannot be further metabolized, leading to accumulation in cells. This leads to an osmotic phenomenon with subsequent cell swelling and ultimately apoptosis [97,98]. The high expression of aldose reductase in the epithelial cells of the lens leads to the formation of galactosemic cataracts [88,99]. Galactitol involvement in cognitive and neurological symptoms has been suggested [61,100]. Pseudotumor cerebri, or elevated intracranial pressure, has also been reported and is postulated to be the result of accumulation of galactitol in the brain cells leading to cerebral edema [101,102].

AR inhibitors have shown to decrease galactitol levels and prevent cataract formation in hypergalactosemia animal models (rats and dogs) [103,104]. By blocking the galactitol accumulation in rats, the increased osmolarity, UPR and ER stress as well as cell death were prevented [105]. In a hypergalactosemia rat model, Mizisin et al. have, furthermore, shown increased sodium concentrations in endoneurinal fluid in rats that are reversible by AR inhibitors indicating a role for galactitol [106,107,108]. Since the exact role of galactitol in the pathophysiological mechanism of galactosemia remains unknown, other than for cataract, decreasing galactitol levels in other organs might show additional beneficial effects. However, caution needs to be taken since the effect of blocking the polyol pathway that converts galactose into the polyol (sugar alcohol) galactitol, is unknown. An increase in Gal-1-P and galactonate might occur, of which the effects remain to be investigated. AR inhibitors are currently being investigated by the biopharmaceutical company Applied Therapeutics [109].

2.2.3. Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress Reducers

ER stress has been shown to be involved in the pathology of classic galactosemia, leading to altered signaling pathways, such as the PI3K/Akt pathway [38,41,42]. Balakrishnan et al. have shown that the downregulation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays an important role in subfertility and cerebellar ataxia in galactosemic mice (n = 6) [38]. This indicates that reduced ER stress might be of therapeutic interest for the brain and ovary, suggesting a possible role for eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) inhibitors that reverse the downregulated pathway in fertility preservation and neurological complications. Positive effects of the eIF2α inhibitor salubrinal have been reported in a mouse model of classic galactosemia without detectable adverse effects [39,110]. Moreover, a protective effect on primordial follicle loss, and an increase in fertility, was found [39]. Although salubrinal is an experimental compound, these findings indicate that the downregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is a valid potential treatment target in classic galactosemia.

2.3. Address the Clinical Picture

2.3.1. Neonatal Period

A galactose-restricted diet resolves the neonatal clinical picture [111]. Newborn screening (NBS) for galactosemia has been implemented in many countries [112,113,114,115,116], and NBS and introduction of diet in the first week of life have shown a beneficial effect [6]. Over the years the strictness of the diet has been questioned and the current recommendation is to eliminate sources of lactose and galactose from dairy products, but permit small amounts of galactose from non-milk sources [111].

2.3.2. Beyond the Neonatal Period

Approaches specifically aimed in tackling the clinical consequences of galactosemia beyond the neonatal period cover the many aspects of the plethora of signs and symptoms associated with GALT-deficiency. In the next paragraphs we touch upon several recent developments regarding (i) fertility preservation, and (ii) neurological and cognitive complications.

Fertility Preservation

Primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) with ovarian follicular depletion leading to subfertility is reported in at least 80% of female patients despite a galactose-restricted diet, representing a heavy burden for female patients [6,117,118,119,120,121]. The etiology of ovarian failure and timing of ovarian damage (pre- or postnatal) have not yet been resolved, although studies suggest that follicular depletion has an early initiation [117,120,122,123,124]. Ovarian imaging results show an early onset of ovarian failure (n = 14) [125]. Moreover, Mamsen et al. have shown normal follicle morphology and follicle densities in galactosemic girls under 5 years (n = 5) [122]. This is supported by the finding of low anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels and low antral follicle counts relative to age-matched controls, suggesting that follicular dysfunction occurs early in life [126,127]. Although spontaneous conception despite POI occurs in classic galactosemia [125,128,129], the chances of pregnancy are severely reduced and fertility preservation options are important. Nowadays, two options are available, cryopreservation and oocyte donation.

The early occurrence of damage supports cryopreservation of ovarian tissue at a very young age as a treatment option [122,125]. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue has been applied for several years to preserve fertility in patients with (mostly) malignant pathologies that undergo treatments with a detrimental effect on fertility. In recent years, the optimization of cryopreservation strategies and thawing/warming protocols has been achieved, expanding the opportunities for females with various pathologies [130,131]. In classic galactosemia, cryopreservation has to be performed at a very young age, because of the early ovarian damage. Even though this procedure is traditionally associated with a reduction in the ovarian reserve, the technology has improved tremendously over the years [131], and it is now associated with a complication rate of merely 0.2% and an increasing success rate [122,132].

Another approach is intrafamilial oocyte donation (mother-to-daughter or sister-to-sister). In the last five years, a group of experts provided recommendations required to optimally address this option taking into account the professionals as well as the patients and family members views. Topics recommended to be discussed are: family relations, medical impact, patient’s cognitive level, agreements to be made in advance and organization of counseling, disclosure to the child, and need for follow-up [133].

The broad phenotypic spectrum of cognitive and neurological impairments that these female patients might develop make decisions around these complex matters challenging.

Neurological and Cognitive Complications

Brain impairments in classic galactosemia, consisting of neurological, cognitive and behavioral complications, are common and are known to have a significant impact on quality of life and general performance [6,134,135,136,137,138,139,140]. Brain impairments have been reported in 85% of patients, including developmental and language delay, neurological complications, language and speech disorders as well as mental and behavioral problems [6]. Structural changes in white and grey matter and functional alterations have been reported [134,135,136,137,138,139].

In addition to the current battery of approaches that are used to help the patients that develop these complications [111], two interesting approaches are currently under study to positively influence language and motor function. One of them is transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS), a form of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS). The rationale behind tACS is to stimulate the naturally occurring rhythmic patterns of electrophysiological activity, also known as brain oscillations, which have been found to be different in classic galactosemia (manuscript in preparation), and modify the oscillations through the delivery of alternating electric currents to the scalp inducing long-term synaptic plasticity [141,142,143,144,145]. Functional networks rely on the synchronization of brain oscillations between the different components of the network, making it an appealing approach for restoring affected functional networks in classic galactosemia [142]. This approach is widely used in cognitive neuroscience, and proven to be efficient in Parkinson and dyslexia and is emerging within the field of psychiatry [141,142,144]. Whether there is proof of concept for this approach is currently under investigation.

The other interesting approach is the Babble Boot Camp (BBC), which is focused on a proactive speech and language intervention program [146]. Current guidelines recommend regular extensive screening for speech and language delay, if children do not meet appropriate levels of speech or language treatment is initiated preferably during the first year of life [111]. However, since speech and language can be regarded as later-developing skill, deficits and signs of delay will only become apparent after an age greater than 24 and 36 months, respectively [111,146]. This approach focuses on a preventive intervention program starting at 2 to 4 months of age and consisting of active parental involvement guided by an expert speech language pathologist. Although the results are preliminary and generalizations cannot be made, a trend to beneficial effects on speech and language development was shown [146].

3. Conclusions

In recent years, several therapeutic approaches intended to provide more adequate treatment for classic galactosemia and prevent burdensome long-term complications have been researched. These approaches aim to (i) restore GALT activity, (ii) influence the cascade of events and (iii) address the clinical picture. Gene therapy and mRNA therapy are emerging therapies within the field of medicine, which show great potential in restoring GALT activity levels in animal models. Pharmacological chaperones form an interesting therapeutic approach for rescuing GALT protein, although this approach is genetic variant-specific as opposed to gene therapy or mRNA therapy. Downstream phenomena that are currently being explored aim to reduce ER stress and inhibit GALK1 or AR. Therapeutic strategies specifically tackling the clinical consequences of classic galactosemia are also evolving. For optimal treatment, the window of opportunity is urged to be characterized, defining when treatment is best given for the different complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization B.D., A.I.C. and M.E.R.-G.; writing—original draft preparation B.D., A.I.C. and M.E.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| AR | Aldose reductase |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BBC | Babble Boot Camp |

| Cas13 | CRISPR-associated protein |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| Dpf | Days post fertilization |

| eIF2α | Eukaryotic initiation factor 2α |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| Gal-1-P | Galactose-1-phosphate |

| GALE | UDP-galactose 4-epimerase |

| GALK1 | Galactokinase 1 |

| GALM | Galactose mutarotase |

| GalNet | Galactosemias Network |

| GALT | Galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase |

| GDH | Galactose dehydrogenase |

| GHMP | Galacto-, homoserine-, mevalonate- and phosphomevalonate kinase |

| Glc-1-P | Glucose-1-phosphate |

| hGALT | human GALT |

| HTS | High throughput screening |

| LNP | Lipid nanoparticle |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NBS | Newborn screening |

| NIBS | Non-invasive brain stimulation |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B |

| POI | Primary ovarian insufficiency |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| tACS | Transcranial alternating current stimulation |

| UGP | UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase |

| UDP | Uridine diphosphate |

| UDP-Gal | Uridine diphosphate-galactose |

| UDP-Glc | Uridine diphosphate-glucose |

| UDP-GalNAc | UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine |

| UDP-GlcNAc | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

References

- 1.Coelho A.I., Berry G.T., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Galactose metabolism and health. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2015;18:422–427. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coelho A.I., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Vicente J.B., Rivera I. Sweet and sour: An update on classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0029-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demirbas D., Coelho A.I., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Berry G.T. Hereditary galactosemia. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2018;83:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haskovic M., Coelho A.I., Bierau J., Vanoevelen J.M., Steinbusch L.K.M., Zimmermann L.J.I., Villamor-Martinez E., Berry G.T., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Pathophysiology and targets for treatment in hereditary galactosemia: A systematic review of animal and cellular models. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jimd.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCorvie T.J., Kopec J., Pey A.L., Fitzpatrick F., Patel D., Chalk R., Shrestha L., Yue W.W. Molecular basis of classic galactosemia from the structure of human galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016;25:2234–2244. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Haskovic M., Bosch A.M., Burnyte B., Coelho A.I., Cassiman D., Couce M.L., Dawson C., Demirbas D., Derks T., et al. The natural history of classic galactosemia: Lessons from the GalNet registry. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019;14:86. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timson D.J. The molecular basis of galactosemia—Past, present and future. Gene. 2016;589:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada Y., Kikuchi A., Arai-Ichinoi N., Sakamoto O., Takezawa Y., Iwasawa S., Niihori T., Nyuzuki H., Nakajima Y., Ogawa E., et al. Biallelic GALM pathogenic variants cause a novel type of galactosemia. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2019;21:1286–1294. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antshel K.M., Epstein I.O., Waisbren S.E. Cognitive strengths and weaknesses in children and adolescents homozygous for the galactosemia Q188R mutation: A descriptive study. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:658–664. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosch A.M., Grootenhuis M.A., Bakker H.D., Heijmans H.S., Wijburg F.A., Last B.F. Living with classical galactosemia: Health-related quality of life consequences. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e423–e428. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert C., Boneh A. The impact of galactosaemia on quality of life—A pilot study. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2004;27:601–608. doi: 10.1023/B:BOLI.0000042957.98782.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang M., Odejinmi S.I., Vankayalapati H., Wierenga K.J., Lai K. Innovative therapy for Classic Galactosemia—Tale of two HTS. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waisbren S.E., Albers S., Amato S., Ampola M., Brewster T.G., Demmer L., Eaton R.B., Greenstein R., Korson M., Larson C., et al. Effect of expanded newborn screening for biochemical genetic disorders on child outcomes and parental stress. JAMA. 2003;290:2564–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waisbren S.E., Rones M., Read C.Y., Marsden D., Levy H.L. Brief report: Predictors of parenting stress among parents of children with biochemical genetic disorders. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2004;29:565–570. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Bosch A.M., Burlina A., Berry G.T., Treacy E.P. The galactosemia network (GalNet) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:169–170. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9989-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasquali M., Yu C., Coffee B. Laboratory diagnosis of galactosemia: A technical standard and guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2018;20:3–11. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calderon F.R., Phansalkar A.R., Crockett D.K., Miller M., Mao R. Mutation database for the galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) gene. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:939–943. doi: 10.1002/humu.20544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coelho A.I., Trabuco M., Ramos R., Silva M.J., Tavares de Almeida I., Leandro P., Rivera I., Vicente J.B. Functional and structural impact of the most prevalent missense mutations in classic galactosemia. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2014;2:484–496. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coelho A.I., Bierau J., Lindhout M., Achten J., Kramer B.W., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Classic Galactosemia: Study on the Late Prenatal Development of GALT Specific Activity in a Sheep Model. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 2017;300:1570–1575. doi: 10.1002/ar.23616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daenzer J.M., Jumbo-Lucioni P.P., Hopson M.L., Garza K.R., Ryan E.L., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Acute and long-term outcomes in a Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia occur independently of galactose-1-phosphate accumulation. Dis. Model. Mech. 2016;9:1375–1382. doi: 10.1242/dmm.022988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCorvie T.J., Timson D.J. Chapter 11—Galactosemia: Opportunities for novel therapies. In: Pey A.L., editor. Protein Homeostasis Diseases. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2020. pp. 221–245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wehrli S.L., Berry G.T., Palmieri M., Mazur A., Elsas L., III, Segal S. Urinary galactonate in patients with galactosemia: Quantitation by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Pediatr. Res. 1997;42:855–861. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199712000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machado C.M., De-Souza E.A., De-Queiroz A., Pimentel F.S.A., Silva G.F.S., Gomes F.M., Montero-Lomeli M., Masuda C.A. The galactose-induced decrease in phosphate levels leads to toxicity in yeast models of galactosemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kushner R.F., Ryan E.L., Sefton J.M., Sanders R.D., Lucioni P.J., Moberg K.H., Fridovich-Keil J.L. A Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia. Dis. Model. Mech. 2010;3:618–627. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai K., Langley S.D., Khwaja F.W., Schmitt E.W., Elsas L.J. GALT deficiency causes UDP-hexose deficit in human galactosemic cells. Glycobiology. 2003;13:285–294. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ning C., Reynolds R., Chen J., Yager C., Berry G.T., Leslie N., Segal S. Galactose metabolism in mice with galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase deficiency: Sucklings and 7-week-old animals fed a high-galactose diet. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2001;72:306–315. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross K.L., Davis C.N., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Differential roles of the Leloir pathway enzymes and metabolites in defining galactose sensitivity in yeast. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;83:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan E.L., DuBoff B., Feany M.B., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Mediators of a long-term movement abnormality in a Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia. Dis. Model. Mech. 2012;5:796–803. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang M., Siddiqi A., Witt B., Yuzyuk T., Johnson B., Fraser N., Chen W., Rascon R., Yin X., Goli H., et al. Subfertility and growth restriction in a new galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GALT)—Deficient mouse model. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:1172–1179. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yager C., Ning C., Reynolds R., Leslie N., Segal S. Galactitol and galactonate accumulation in heart and skeletal muscle of mice with deficiency of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2004;81:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haskovic M., Coelho A.I., Lindhout M., Zijlstra F., Veizaj R., Vos R., Vanoevelen J.M., Bierau J., Lefeber D.J., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Nucleotide sugar profiles throughout development in wildtype and galt knockout zebrafish. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020;43:994–1001. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coss K.P., Treacy E.P., Cotter E.J., Knerr I., Murray D.W., Shin Y.S., Doran P.P. Systemic gene dysregulation in classical Galactosaemia: Is there a central mechanism? Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;113:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dobbie J.A., Holton J.B., Clamp J.R. Defective galactosylation of proteins in cultured skin fibroblasts from galactosaemic patients. Pt 3Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1990;27:274–275. doi: 10.1177/000456329002700317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ornstein K.S., McGuire E.J., Berry G.T., Roth S., Segal S. Abnormal galactosylation of complex carbohydrates in cultured fibroblasts from patients with galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase deficiency. Pediatr. Res. 1992;31:508–511. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199205000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petry K., Greinix H.T., Nudelman E., Eisen H., Hakomori S., Levy H.L., Reichardt J.K. Characterization of a novel biochemical abnormality in galactosemia: Deficiency of glycolipids containing galactose or N-acetylgalactosamine and accumulation of precursors in brain and lymphocytes. Biochem. Med. Metab. Biol. 1991;46:93–104. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(91)90054-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staubach S., Müller S., Pekmez M., Hanisch F.G. Classical Galactosemia: Insight into Molecular Pathomechanisms by Differential Membrane Proteomics of Fibroblasts under Galactose Stress. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:516–527. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Erven B. Ph.D Thesis. Maastricht University; Maastricht, The Netherlands: Mar, 2017. Classic galactosemia: A zebrafish model and new clinical insights. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balakrishnan B., Chen W., Tang M., Huang X., Cakici D.D., Siddiqi A., Berry G., Lai K. Galactose-1 phosphate uridylyltransferase (GalT) gene: A novel positive regulator of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in mouse fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;470:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balakrishnan B., Nicholas C., Siddiqi A., Chen W., Bales E., Feng M., Johnson J., Lai K. Reversal of aberrant PI3K/Akt signaling by Salubrinal in a GalT-deficient mouse model. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017;1863:3286–3293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De-Souza E.A., Pimentel F.S.A., Machado C.M., Martins L.S., da-Silva W.S., Montero-Lomelí M., Masuda C.A. The unfolded protein response has a protective role in yeast models of classic galactosemia. Dis. Models Mech. 2014;7:55. doi: 10.1242/dmm.012641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Slepak T., Tang M., Addo F., Lai K. Intracellular galactose-1-phosphate accumulation leads to environmental stress response in yeast model. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2005;86:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slepak T.I., Tang M., Slepak V.Z., Lai K. Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in a novel Classic Galactosemia model. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;92:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jumbo-Lucioni P.P., Hopson M.L., Hang D., Liang Y., Jones D.P., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Oxidative stress contributes to outcome severity in a Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013;6:84–94. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jumbo-Lucioni P.P., Ryan E.L., Hopson M.L., Bishop H.M., Weitner T., Tovmasyan A., Spasojevic I., Batinic-Haberle I., Liang Y., Jones D.P., et al. Manganese-based superoxide dismutase mimics modify both acute and long-term outcome severity in a Drosophila melanogaster model of classic galactosemia. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:2361–2371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen S.A., Daenzer J.M.I., MacWilliams J.A., Head S.T., Williams M.B., Geurts A.M., Schroeder J.P., Weinshenker D., Fridovich-Keil J.L. A galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase-null rat model of classic galactosemia mimics relevant patient outcomes and reveals tissue-specific and longitudinal differences in galactose metabolism. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020;43:518–528. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanoevelen J.M., van Erven B., Bierau J., Huang X., Berry G.T., Vos R., Coelho A.I., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Impaired fertility and motor function in a zebrafish model for classic galactosemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:117–127. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berry G.T. In: Classic Galactosemia and Clinical Variant Galactosemia. Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., Wallace S.E., Bean L.J.H., Stephens K., Amemiya A., editors. GeneReviews®; Seattle, WA, USA: 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walter J., Fridovich-Keil J. Galactosemia. In: Valle D., Beaudet A.L., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W., Antonarakis S.E., Ballabio A., Gibson K., Mitchell G., editors. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (OMMBID) McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cring M.R., Sheffield V.C. Gene therapy and gene correction: Targets, progress, and challenges for treating human diseases. Gene. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41434-020-00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rutten M.G.S., Rots M.G., Oosterveer M.H. Exploiting epigenetics for the treatment of inborn errors of metabolism. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020;43:63–70. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneller J.L., Lee C.M., Bao G., Venditti C.P. Genome editing for inborn errors of metabolism: Advancing towards the clinic. BMC Med. 2017;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0798-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chandler R.J., Venditti C.P. Gene Therapy for Metabolic Diseases. Transl Sci. Rare Dis. 2016;1:73–89. doi: 10.3233/TRD-160007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yilmaz B.S., Gurung S., Perocheau D., Counsell J., Baruteau J. Gene Therapy for Inherited Metabolic Diseases. J. Mother Child. 2020 doi: 10.34763/jmotherandchild.20202402si.2004.000009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rasmussen S.A., Daenzer J.M.I., Fridovich-Keil J.L. A pilot study of neonatal GALT gene replacement using AAV9 dramatically lowers galactose metabolites in blood, liver, and brain and minimizes cataracts in GALT-null rat pups. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jimd.12311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loiler S.A. Gene therapy for the treatment of galactosemia. WO2020047472A1. U.S. Patent. 2019 Aug 30;

- 56.Brophy M.L., Chen T.-W., Le K., Tabet R., Ahn Y., Murphy J.E., Bell R.D. AAV-Mediated Gene Therapy Rescues GALT Activity and Reduces ER Stress in Classic Galactosemia. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:303. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan X., Sands S.A., Yue Y., Zhang K., LeVine S.M., Duan D. An Engineered Galactosylceramidase Construct Improves AAV Gene Therapy for Krabbe Disease in Twitcher Mice. Hum. Gene. 2019;30:1039–1051. doi: 10.1089/hum.2019.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zincarelli C., Soltys S., Rengo G., Rabinowitz J.E. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1-9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kowalski P.S., Rudra A., Miao L., Anderson D.G. Delivering the Messenger: Advances in Technologies for Therapeutic mRNA Delivery. Molecular. 2019;27:710–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martini P.G.V., Guey L.T. A New Era for Rare Genetic Diseases: Messenger RNA Therapy. Hum. Gene. 2019;30:1180–1189. doi: 10.1089/hum.2019.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timson D.J. Therapies for galactosemia: A patent landscape. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 2020;9:45–51. doi: 10.4155/ppa-2020-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zifu Z., Mc Cafferty S., Combes F., Huysmans H., De Temmerman J., Gitsels A., Vanrompay D., Portela Catani J., Sanders N. mRNA therapeutics deliver a hopeful message. Nano Today. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2018.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cullis P.R., Hope M.J. Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies. Molecular. 2017;25:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DeRosa F., Guild B., Karve S., Smith L., Love K., Dorkin J.R., Kauffman K.J., Zhang J., Yahalom B., Anderson D.G., et al. Therapeutic efficacy in a hemophilia B model using a biosynthetic mRNA liver depot system. Gene Ther. 2016;23:699. doi: 10.1038/gt.2016.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kulkarni J.A., Cullis P.R., van der Meel R. Lipid Nanoparticles Enabling Gene Therapies: From Concepts to Clinical Utility. Nucleic Acid. 2018;28:146–157. doi: 10.1089/nat.2018.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Novakowski S., Jiang K., Prakash G., Kastrup C. Delivery of mRNA to platelets using lipid nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:552. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36910-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao W., Hou X., Vick O.G., Dong Y. RNA delivery biomaterials for the treatment of genetic and rare diseases. Biomaterials. 2019;217:119291. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balakrishnan B., An D., Nguyen V., DeAntonis C., Martini P.G.V., Lai K. Novel mRNA-Based Therapy Reduces Toxic Galactose Metabolites and Overcomes Galactose Sensitivity in a Mouse Model of Classic Galactosemia. Molecular. 2020;28:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truong B., Allegri G., Liu X.B., Burke K.E., Zhu X., Cederbaum S.D., Haberle J., Martini P.G.V., Lipshutz G.S. Lipid nanoparticle-targeted mRNA therapy as a treatment for the inherited metabolic liver disorder arginase deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:21150–21159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906182116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berraondo P., Martini P.G.V., Avila M.A., Fontanellas A. Messenger RNA therapy for rare genetic metabolic diseases. Gut. 2019;68:1323–1330. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.An D., Frassetto A., Jacquinet E., Eybye M., Milano J., DeAntonis C., Nguyen V., Laureano R., Milton J., Sabnis S., et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of mRNA therapy in two murine models of methylmalonic acidemia. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.An D., Schneller J.L., Frassetto A., Liang S., Zhu X., Park J.S., Theisen M., Hong S.J., Zhou J., Rajendran R., et al. Systemic Messenger RNA Therapy as a Treatment for Methylmalonic Acidemia. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2520. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiang L., Berraondo P., Jerico D., Guey L.T., Sampedro A., Frassetto A., Benenato K.E., Burke K., Santamaria E., Alegre M., et al. Systemic messenger RNA as an etiological treatment for acute intermittent porphyria. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1899–1909. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0199-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Prieve M.G., Harvie P., Monahan S.D., Roy D., Li A.G., Blevins T.L., Paschal A.E., Waldheim M., Bell E.C., Galperin A., et al. Targeted mRNA Therapy for Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency. Molecular. 2018;26:801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roseman D.S., Khan T., Rajas F., Jun L.S., Asrani K.H., Isaacs C., Farelli J.D., Subramanian R.R. G6PC mRNA Therapy Positively Regulates Fasting Blood Glucose and Decreases Liver Abnormalities in a Mouse Model of Glycogen Storage Disease 1a. Molecular. 2018;26:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haskovic M., Delnoy B., Bierau J., Lindhout M., Zimmermann L.J., Vanoevelen J.M., Coelho A.I., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Ph.D Thesis. Maastricht University; Maastricht, The Netherlands: Oct, 2020. The promise of mRNA therapy as a treatment for classic galactosemia in Classic galactosemia: Natural histroy and new treatment approaches; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fan J.Q. A counterintuitive approach to treat enzyme deficiencies: Use of enzyme inhibitors for restoring mutant enzyme activity. Biol. Chem. 2008;389:1–11. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muntau A.C., Leandro J., Staudigl M., Mayer F., Gersting S.W. Innovative strategies to treat protein misfolding in inborn errors of metabolism: Pharmacological chaperones and proteostasis regulators. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014;37:505–523. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9701-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ulloa-Aguirre A., Janovick J.A., Brothers S.P., Conn P.M. Pharmacologic rescue of conformationally-defective proteins: Implications for the treatment of human disease. Traffic. 2004;5:821–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McCorvie T.J., Gleason T.J., Fridovich-Keil J.L., Timson D.J. Misfolding of galactose 1-phosphate uridylyltransferase can result in type I galactosemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1832:1279–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tang M., Facchiano A., Rachamadugu R., Calderon F., Mao R., Milanesi L., Marabotti A., Lai K. Correlation assessment among clinical phenotypes, expression analysis and molecular modeling of 14 novel variations in the human galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase gene. Hum. Mutat. 2012;33:1107–1115. doi: 10.1002/humu.22093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma S., Sarkar S., Paul S.S., Roy S., Chattopadhyay K. A small molecule chemical chaperone optimizes its unfolded state contraction and denaturant like properties. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3525. doi: 10.1038/srep03525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coelho A.I., Trabuco M., Silva M.J., de Almeida I.T., Leandro P., Rivera I., Vicente J.B. Arginine Functionally Improves Clinically Relevant Human Galactose-1-Phosphate Uridylyltransferase (GALT) Variants Expressed in a Prokaryotic Model. JIMD Rep. 2015;23:1–6. doi: 10.1007/8904_2015_420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Haskovic M., Derks B., van der Ploeg L., Trommelen J., Nyakayiru J., van Loon L.J.C., Mackinnon S., Yue W.W., Peake R.W.A., Zha L., et al. Arginine does not rescue p.Q188R mutation deleterious effect in classic galactosemia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018;13:212. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0954-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Timson D.J. Purple sweet potato colour—A potential therapy for galactosemia? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014;65:391–393. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2013.860586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bosch A.M., Bakker H.D., van Gennip A.H., van Kempen J.V., Wanders R.J., Wijburg F.A. Clinical features of galactokinase deficiency: A review of the literature. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2002;25:629–634. doi: 10.1023/A:1022875629436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hennermann J.B., Schadewaldt P., Vetter B., Shin Y.S., Monch E., Klein J. Features and outcome of galactokinase deficiency in children diagnosed by newborn screening. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Derks B., Das A.M., Meyer U., Moslinger D., Couce M.L., Empain A., Ficicioglu C., Julia Palacios N., De Los Santos De Pelegrin M.M., et al. Galactokinase deficiency: Lessons from the GalNet registry. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-00942-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Odejinmi S., Rascon R., Tang M., Vankayalapati H., Lai K. Structure-activity analysis and cell-based optimization of human galactokinase inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:667–672. doi: 10.1021/ml200131j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tang M., Wierenga K., Elsas L.J., Lai K. Molecular and biochemical characterization of human galactokinase and its small molecule inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;188:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hu X., Zhang Y.Q., Lee O.W., Liu L., Tang M., Lai K., Boxer M.B., Hall M.D., Shen M. Discovery of novel inhibitors of human galactokinase by virtual screening. J. Comput Aided Mol. Des. 2019;33:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s10822-019-00190-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu L., Tang M., Walsh M.J., Brimacombe K.R., Pragani R., Tanega C., Rohde J.M., Baker H.L., Fernandez E., Blackman B., et al. Structure activity relationships of human galactokinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.McAuley M., Mesa-Torres N., McFall A., Morris S., Huang M., Pey A.L., Timson D.J. Improving the Activity and Stability of Human Galactokinase for Therapeutic and Biotechnological Applications. ChemBioChem. 2018;19:1088–1095. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201800025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wierenga K.J., Lai K., Buchwald P., Tang M. High-throughput screening for human galactokinase inhibitors. J. Biomol. Screen. 2008;13:415–423. doi: 10.1177/1087057108318331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lai K., Boxer M.B., Marabotti A. GALK inhibitors for classic galactosemia. Future Med. Chem. 2014;6:1003–1015. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.De Jongh W.A., Bro C., Ostergaard S., Regenberg B., Olsson L., Nielsen J. The roles of galactitol, galactose-1-phosphate, and phosphoglucomutase in galactose-induced toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;101:317–326. doi: 10.1002/bit.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lai K., Elsas L.J., Wierenga K.J. Galactose toxicity in animals. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:1063–1074. doi: 10.1002/iub.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pintor J. Sugars, the crystalline lens and the development of cataracts. Biochem. Pharm. 2012;1:1–3. doi: 10.4172/2167-0501.1000e119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ai Y., Zheng Z., O’Brien-Jenkins A., Bernard D.J., Wynshaw-Boris T., Ning C., Reynolds R., Segal S., Huang K., Stambolian D. A mouse model of galactose-induced cataracts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1821–1827. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.12.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kamijo M., Basso M., Cherian P.V., Hohman T.C., Sima A.A. Galactosemia produces ARI-preventable nodal changes similar to those of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 1994;25:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90037-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Berry G.T., Hunter J.V., Wang Z., Dreha S., Mazur A., Brooks D.G., Ning C., Zimmerman R.A., Segal S. In vivo evidence of brain galactitol accumulation in an infant with galactosemia and encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2001;138:260–262. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.110423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Huttenlocher P.R., Hillman R.E., Hsia Y.E. Pseudotumor cerebri in galactosemia. J. Pediatr. 1970;76:902–905. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(70)80373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lou M.F., Dickerson J.E., Jr., Chandler M.L., Brazzell R.K., York B.M., Jr. The prevention of biochemical changes in lens, retina, and nerve of galactosemic dogs by the aldose reductase inhibitor AL01576. J. Ocul. Pharm. 1989;5:233–240. doi: 10.1089/jop.1989.5.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Obrosova I., Faller A., Burgan J., Ostrow E., Williamson J.R. Glycolytic pathway, redox state of NAD(P)-couples and energy metabolism in lens in galactose-fed rats: Effect of an aldose reductase inhibitor. Curr. Eye Res. 1997;16:34–43. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.1.34.5113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mulhern M.L., Madson C.J., Danford A., Ikesugi K., Kador P.F., Shinohara T. The unfolded protein response in lens epithelial cells from galactosemic rat lenses. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:3951–3959. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mizisin A.P., Myers R.R., Powell H.C. Endoneurial sodium accumulation in galactosemic rat nerves. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:440–444. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mizisin A.P., Powell H.C. Schwann cell injury is attenuated by aldose reductase inhibition in galactose intoxication. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1993;52:78–86. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mizisin A.P., Powell H.C., Myers R.R. Edema and increased endoneurial sodium in galactose neuropathy. Reversal with an aldose reductase inhibitor. J. Neurol. Sci. 1986;74:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(86)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.ClinicalTrials.gov. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). Identifier NCT04117711, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of AT-007 in Healthy Subjects and in Adult Subjects With Classic Galactosemia; 2019 Oct 07. [(accessed on 27 January 2021)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04117711.

- 110.Balakrishnan B., Siddiqi A., Mella J., Lupo A., Li E., Hollien J., Johnson J., Lai K. Salubrinal enhances eIF2α phosphorylation and improves fertility in a mouse model of Classic Galactosemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019;1865:165516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Welling L., Bernstein L.E., Berry G.T., Burlina A.B., Eyskens F., Gautschi M., Grunewald S., Gubbels C.S., Knerr I., Labrune P., et al. International clinical guideline for the management of classical galactosemia: Diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s10545-016-9990-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pollitt R.J., Green A., McCabe C.J., Booth A., Cooper N.J., Leonard J.V., Nicholl J., Nicholson P., Tunaley J.R., Virdi N.K. Neonatal screening for inborn errors of metabolism: Cost, yield and outcome. Health Technol. Assess. 1997;1:i–iv. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Schweitzer-Krantz S. Early diagnosis of inherited metabolic disorders towards improving outcome: The controversial issue of galactosaemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003;162(Suppl. S1):S50–S53. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shah V., Friedman S., Moore A.M., Platt B.A., Feigenbaum A.S. Selective screening for neonatal galactosemia: An alternative approach. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:948–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2001.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Waisbren S.E., Read C.Y., Ampola M., Brewster T.G., Demmer L., Greenstein R., Ingham C.L., Korson M., Msall M., Pueschel S., et al. Newborn screening compared to clinical identification of biochemical genetic disorders. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2002;25:599–600. doi: 10.1023/A:1022003726224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Walter J.H. Arguments for early screening: A clinician’s perspective. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2003;162(Suppl. S1):S2–S4. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1340-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Abidin Z., Treacy E.P. Insights into the Pathophysiology of Infertility in Females with Classical Galactosaemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:5236. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gubbels C.S., Land J.A., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Fertility and impact of pregnancies on the mother and child in classic galactosemia. Obs. Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:334–343. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31816ff6c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kaufman F., Kogut M.D., Donnell G.N., Koch R., Goebelsmann U. Ovarian failure in galactosæmia. Lancet. 1979;314:737–738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)90658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Gubbels C.S., Bakker J.A., Menheere P.P., Wodzig W.K., Land J.A. Gonadal function in male and female patients with classic galactosemia. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2010;16:177–188. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Waggoner D.D., Buist N.R., Donnell G.N. Long-term prognosis in galactosaemia: Results of a survey of 350 cases. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1990;13:802–818. doi: 10.1007/BF01800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mamsen L.S., Kelsey T.W., Ernst E., Macklon K.T., Lund A.M., Andersen C.Y. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue may be considered in young girls with galactosemia. J. Assist. Reprod Genet. 2018;35:1209–1217. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1209-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sozen B., Ozekinci M., Erman M., Gunduz T., Demir N., Akouri R. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation attenuates ovarian ageing in a galactose-induced primary ovarian insufficiency rat model. J. Assist. Reprod Genet. 2019;36:2181–2189. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01560-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Thakur M., Feldman G., Puscheck E.E. Primary ovarian insufficiency in classic galactosemia: Current understanding and future research opportunities. J. Assist. Reprod Genet. 2018;35:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-1039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gubbels C.S., Land J.A., Evers J.L., Bierau J., Menheere P.P., Robben S.G., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Primary ovarian insufficiency in classic galactosemia: Role of FSH dysfunction and timing of the lesion. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2013;36:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9497-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sanders R.D., Spencer J.B., Epstein M.P., Pollak S.V., Vardhana P.A., Lustbader J.W., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Biomarkers of ovarian function in girls and women with classic galactosemia. Fertil. Steril. 2009;92:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Spencer J.B., Badik J.R., Ryan E.L., Gleason T.J., Broadaway K.A., Epstein M.P., Fridovich-Keil J.L. Modifiers of ovarian function in girls and women with classic galactosemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:E1257–E1265. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Van Erven B., Berry G.T., Cassiman D., Connolly G., Forga M., Gautschi M., Gubbels C.S., Hollak C.E.M., Janssen M.C., Knerr I., et al. Fertility in adult women with classic galactosemia and primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil. Steril. 2017;108:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Van Erven B., Gubbels C.S., van Golde R.J., Dunselman G.A., Derhaag J.G., de Wert G., Geraedts J.P., Bosch A.M., Treacy E.P., Welt C.K., et al. Fertility preservation in female classic galactosemia patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013;8:107. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gamzatova Z., Komlichenko E., Kostareva A., Galagudza M., Ulrikh E., Zubareva T., Sheveleva T., Nezhentseva E., Kalinina E. Autotransplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue—Effective method of fertility preservation in cancer patients. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2014;30(Suppl. S1):43–47. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.945789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rivas Leonel E.C., Lucci C.M., Amorim C.A. Cryopreservation of Human Ovarian Tissue: A Review. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2019;46:173–181. doi: 10.1159/000499054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Beckmann M.W., Dittrich R., Lotz L., van der Ven K., van der Ven H.H., Liebenthron J., Korell M., Frambach T., Sutterlin M., Schwab R., et al. Fertility protection: Complications of surgery and results of removal and transplantation of ovarian tissue. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2018;36:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.10.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Haskovic M., Poot W.J., van Golde R.J.T., Benneheij S.H., Oussoren E., de Wert G., Krumeich A., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Intrafamilial oocyte donation in classic galactosemia: Ethical and societal aspects. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:791–797. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Timmers I., Jansma B.M., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. From mind to mouth: Event related potentials of sentence production in classic galactosemia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Timmers I., van den Hurk J., Hofman P.A., Zimmermann L.J., Uludag K., Jansma B.M., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Affected functional networks associated with sentence production in classic galactosemia. Brain Res. 2015;1616:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Timmers I., van der Korput L.D., Jansma B.M., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E. Grey matter density decreases as well as increases in patients with classic galactosemia: A voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Res. 2016;1648:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Van Erven B., Jansma B.M., Rubio-Gozalbo M.E., Timmers I. Exploration of the Brain in Rest: Resting-State Functional MRI Abnormalities in Patients with Classic Galactosemia. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:9095. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09242-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Welsink-Karssies M.M., Oostrom K.J., Hermans M.E., Hollak C.E.M., Janssen M.C.H., Langendonk J.G., Oussoren E., Rubio Gozalbo M.E., de Vries M., Geurtsen G.J., et al. Classical galactosemia: Neuropsychological and psychosocial functioning beyond intellectual abilities. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020;15:42. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Welsink-Karssies M.M., Schrantee A., Caan M.W.A., Hollak C.E.M., Janssen M.C.H., Oussoren E., de Vries M.C., Roosendaal S.D., Engelen M., Bosch A.M. Gray and white matter are both affected in classical galactosemia: An explorative study on the association between neuroimaging and clinical outcome. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hermans M.E., Welsink-Karssies M.M., Bosch A.M., Oostrom K.J., Geurtsen G.J. Cognitive functioning in patients with classical galactosemia: A systematic review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019;14:226. doi: 10.1186/s13023-019-1215-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Del Felice A., Castiglia L., Formaggio E., Cattelan M., Scarpa B., Manganotti P., Tenconi E., Masiero S. Personalized transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) and physical therapy to treat motor and cognitive symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized cross-over trial. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;22:101768. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Elyamany O., Leicht G., Herrmann C.S., Mulert C. Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS): From basic mechanisms towards first applications in psychiatry. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Riddle J., Rubinow D.R., Frohlich F. A case study of weekly tACS for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2020;13:576–577. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rufener K.S., Krauel K., Meyer M., Heinze H.J., Zaehle T. Transcranial electrical stimulation improves phoneme processing in developmental dyslexia. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:930–937. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tavakoli A.V., Yun K. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) Mechanisms and Protocols. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:214. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Peter B., Potter N., Davis J., Donenfeld-Peled I., Finestack L., Stoel-Gammon C., Lien K., Bruce L., Vose C., Eng L., et al. Toward a paradigm shift from deficit-based to proactive speech and language treatment: Randomized pilot trial of the Babble Boot Camp in infants with classic galactosemia. F1000Research. 2019;8:271. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18062.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.